关于“游戏化”定义和设计方向的思考

作者:Zachary Fitz-Walter

我或许有点多疑,但我确实觉得游戏时刻都围绕在自己身边。我每次使用Foursquare向好友分享所处的地点时会获得分数和徽章,完成制定的任务让我上周在《Epic Win》计划列表应用中提升2级,我昨晚的跑步在应用中超过了两个僵尸暴徒。这些应用都是去年“游戏化”(Gamification)大趋势中的一员。

游戏化被视为吸引用户参与到产品中的方法,市场中“游戏化”产品的数量正在不断增加,到2015年我们将会看到50%的企业或组织会将他们的创新过程游戏化。游戏化也被当成流行语四处传播,这个毫无意义的词汇充满了对提升用户忠诚度的承诺。

但是,当我们试图理解游戏化真正的含义,将其从严肃或无处不在、善于说服用户的游戏概念中分离出来,努力认清何为真正的游戏化时,问题便产生了。然而,无论是将游戏元素运用到非游戏背景下还是制作真正的游戏,使用游戏和游戏元素背后的驱动力是相同的,都是要通过趣味性来激发和吸引用户。如果真实情况如此,那么专注点应该在游戏元素的设计上,运用游戏设计理论,理解玩游戏的动机,这样才能制作出能够保持人们不断玩下去的最具吸引力的玩家体验。

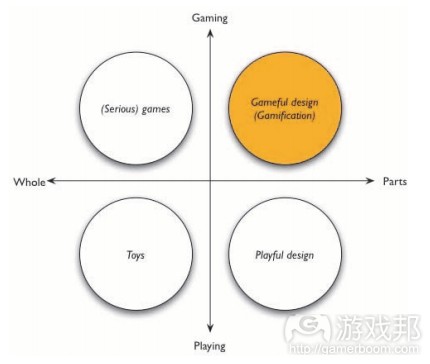

定义游戏化。尽管这个词语到现在为止已经存在了数年时间,但是很少人试图从科学的角度来给这个术语下定义。最完整和可靠的定义来源于Deterding、Dixon、Khaled和Nacke,他们将游戏化定义为“在非游戏背景下使用游戏设计元素”。他们的目标是利用这个定义将游戏化(游戏邦注:或者也可以称为“游戏般设计”)同玩具、玩乐设计和真正游戏区分开来,区分元素分为两个对立部分,分别是玩乐与游戏,整体与局部。

在这种定义方法中,游戏化可以被认为更贴近于游戏(游戏邦注:结构化并带有明确的规则)而不是整合玩乐元素的设计(游戏邦注:非结构化且是自发行为)。而且,游戏化术语指的是带有游戏元素的产品,并非真正的成熟游戏,但是作者也承认,在最佳情况下这两者间的界限会变得模糊。以Foursquare为例,它算是游戏还是带有游戏元素的手机应用呢?这取决于多个方面,比如人们如何使用它或者设计师制作这款应用是出于何种意图。就游戏元素而言,可能是游戏中的任何东西,从图像和进度条等游戏美学元素到带有长远目标、规则、故事、关卡、探索和成就的完整游戏。将事物游戏化意味着将以上列举的任意数量的游戏元素添加到非游戏背景中,提升其用户体验或增加其吸引力。总体来说,通常游戏化的目标是制作更具吸引力的产品或创建更活跃和积极的用户群体。比如,看看以下两款不同的计划类应用程序,左边是《Remember the Milk》,右边是《Epic Win》。

《Remember the Milk》是款强大的iPhone计划列表应用程序,带有所有你需要的功能,可以添加新计划和标注已完成的任务。反之,《Epic Win》是款看起来更像游戏中任务记录的iPhone应用程序,但事实上它也是款计划列表应用程序,只是采用了许多游戏元素,比如游戏美学元素、语言、化身、等级、经验值、战利品和地图。这两款应用程序提供了相同的基本功能,但是通过整合游戏元素,《Epic Win》试图通过将完成任务的动作转化成游戏任务架构以让过程变得更有趣味性和吸引力。游戏化已经广泛传播到各个不同的领域,包括医疗、教育、绿色生态和软件应用程序。所以,这听起来是个很棒的东西,不是吗?的确,这样的做法能产生令人惊叹的效果,但是你要如何使用游戏化技术?如何设计才能产生这种游戏般体验呢?

通用元素:徽章、排行榜和分数

如果你有个网站,那么你可以使用Bunchball和Badgeville等供应商提供的“即时游戏化平台”服务,将游戏元素整合其中。这些游戏化平台提供许多通用方法,可添加到网站上的游戏元素能够提升用户的参与度。他们提供API和组件,站点管理者可以用来奖励用户的某些行为,比如评论、注册、购买、社交分享和参与带有虚拟游戏奖励的问答比赛,奖励可以是等级、分数、成就或特别礼物和额外内容等有形奖励。

问题在于,这些类型的游戏元素主要是基于奖励的元素,其目标是从外部激励用户。这种设计缺乏让游戏显得有趣的基本元素。要进一步理解这个方面,让我们来简单地讨论下动机理论。动机分为外在动机和内在动机两种类型,这是众人普遍接受的说法。当为了获得某些外在或可分离结果而做出行动时,起作用的便是外在动机,比如努力工作以获得提薪或晋升。相反,当做出行动的目标是为了获得进行行为本身的内在满足感,那么起作用的就是内在动机,比如为了工作中的乐趣而工作。玩游戏这个行为通常被视为追求愉悦和内在满足感的行为。因而,游戏化背后的想法通常是试图利用这种人们从游戏中体验到的愉悦和趣味性,将其用来以游戏般的形式架构非游戏内容,使它们显得更具趣味性和吸引力。但是,当奖励成为游戏化设计中使用的主要元素时,便会产生问题。无论这种奖励是分数、徽章还是实物奖励,他们都只是促进用户完成任务的外在动机,比如编写3个帖子可以解锁成就!这些正是目前游戏化的最大问题,它们主要以奖励为基础来激励用户,却没有更大的目标或者未曾考虑过任务的挑战性。出现这种情况有一定的原因,这些类型的奖励系统的执行都很简单而廉价,可以被运用到任何系统能够轻易检测到的数量化动作上(游戏邦注:比如在网站上发布的评论数量)。但是,如果要真正创造吸引人的游戏化体验,奖励根本不足以让用户感到满意。于是,我们面临的问题是,什么东西能够帮助我们制作出更具愉悦性的游戏化设计呢?

转向玩家愉悦和游戏动机

如果玩游戏的行为被普遍视为追求愉悦和内在满足的行为,那么我们应当考虑是什么激励玩家去玩游戏。Ryan等人猜想,游戏的主要激励点在于,玩家在游戏过程中能够体验到自主性、能力和关联性,这是产生内在动机的3个基本心理学需求。这个理论被称为“自决理论”。

如果向非游戏内容添加游戏元素能够以类似游戏的方法激励用户,那么支持这3种心理需求便有可能创造出更具愉悦性的游戏化体验。通过这种愉悦性,运用游戏元素的非游戏内容的参与度便有可能增加。自主指玩家做出的选择及其原因。当玩家选择出于自身兴趣或个人价值而不是奖励或被迫做出某种行动时,他们感知到的就是很高的自主性。如果游戏化是个添加到非游戏内容中的可选元素,玩家可以选择是否参与其中,那么玩家的自主感就会很高。在游戏化设计中,如果玩家可以自由选择做出动作的顺序,没有被迫采取某种特别的发展方式,那么自主感就会很高。能力指最优化挑战人们的能力,在游戏中,如果控制方法简单直观,游戏中的任务会持续不断地提供最优化挑战和积极反馈的机遇,那么玩家的能力感就会很高。权力还与心流理论有关,这是个由Csíkszentmihályi提出的特别动机理论,描述人们完全沉浸在活动中时的精神状态。要提升心流层次,就需要提供适合用户技能等级的挑战。过难的挑战会让人们觉得焦虑和难以承受,过于容易的挑战又会让人觉得乏味无趣。

最后,关联性指人们与他人的联系,在游戏中,他人可能是电脑生成的人或其他玩家。互动、联系和照顾他人的体验需求能够成为强大的动机。如果能够在为非游戏内容设计游戏元素的过程中考虑到这3个元素,而不是简单地通过奖励进行激励,那么玩家或许会更大程度地参与到非游戏内容中。

总结

我在这篇文章中讨论了许多内容,包括普通游戏和游戏化间的联系、使用游戏化来呈现不同层次的外在动机、结合非游戏内容目标和动作与游戏目标和动作的重要性等,但只是希望这些内容能够激发你开始更多地思考这个领域的内涵。游戏化是个全新的领域,仍然存在许多值得研究和探索的地方。我个人对这方面很感兴趣,乐衷于研究向非游戏内容构建有意义的游戏动作和目标的重要性和探索通过提升游戏化设计中的玩家愉悦来强化动机。我的目标是,采用游戏理论中的玩家参与度模型,指导未来的游戏化设计,尤其是手机内容的设计。这些指导意见将通过大量案例研究来评估,首个目标是将日常上下班过程转变成游戏,从而鼓励绿色交通。现在,是开始这方面研究的时候了!

游戏邦注:本文发稿于2012年4月26日,所涉时间、事件和数据均以此为准。(本文为游戏邦/gamerboom.com编译,拒绝任何不保留版权的转载,如需转载请联系:游戏邦)

Gamification: Thoughts on definition and design

Zachary Fitz-Walter

I might be a little paranoid but I think games are starting to follow me around. I get points and badges every time I share my location with friends using Foursquare, I’ve levelled up twice in the last week just by completing tasks on the Epic Win to do list app and I outran two zombie mobs during my run last night. These apps are part of a bigger trend that has gained immense popularity over the last year or so known as gamification.

Gamification is being heralded as the way to engage users with products and the number of ‘gamified’ products hitting the market is increasing so much so that by the year 2015 we could see 50% of all organisations gamifying their innovation processes. Gamification is also being tossed around as simply a buzzword, a meaningless word full of promises of increasing user loyalty – potentially something that could potentially provide the missing step for the gnomes from South Park?

(The missing step?)

However, difficulty arises when attempting to understand what gamification exactly means, separating it from the notion of serious or pervasive, persuasive games and then trying to classify what exactly is gamified and what isn’t. However, regardless of whether it’s game elements being used in a non-game context or if it’s a complete serious game, the drive behind using games and game elements in this way is the same; to motivate and engage through fun and enjoyment. If this is the case then the focus should be on the design of the game elements, drawing from game design theory and understanding the motivation to play games in order to create the most engaging player experience that will keep people playing.

Defining Gamification. Although the word has been around for a couple of years now there have been few attempts to define the term scientifically. The most complete and solid definition proposed has been by Deterding, Dixon, Khaled and Nacke who define gamification as “the use of game design elements in non-game contexts”. With this definition the authors aim to separate gamification (or alternatively ‘gameful design’) from toys, playful design and (serious) games in terms of two dimensions, one that distinguishes between playing and gaming and the other between whole and parts.

(Where gamification sits)

In this way gamification can be seen as relating closer to games (i.e. structured and with explicit rules) rather than design that incorporates elements of play (i.e. unstructured and spontaneous). Also, the term gamification denotes an artifact with game elements rather than a full-fledged game but the authors do note that this boundary between these two can be blurry at the best of times. Take for example Foursquare, is it a game or a mobile app with game elements? This could depend on a number of things such as how people use it or on what the designer intended. In terms of a game element, this could potentially be anything from game aesthetics such as graphics and progress bars, to complete games with an overarching goal, rules, story, levels, quests and achievements all powered by real actions. Gamifying something entails adding any number of game elements, such as those listed, to a non-game context to enhance the user experience or increase motivation and engagement. Overall gamification generally has the goal to make a more appealing product or create a more active and motivated user base. For an example, have a look at the two different to-do applications below, on the left is Remember the Milk and on the right is Epic Win.

(Remember the Milk vs. the game-like Epic Win)

Remember the Milk has a robust to-do list iPhone application with all the functions you need in order to add and check off completed tasks. The Epic Win iPhone application on the other hand looks more like a quest log in a game, however it is in fact another to-do list application that employs a number of game elements such as game aesthetics, language, avatars, levelling, experience points, loot and maps. Both applications provide the same basic functionality however by integrating game elements, Epic Win attempts to make the action of completing tasks fun, playful and engaging by framing them as epic quests. The adoption of gamification in both industry and research has been wide spread over a range of different domains including health, education, greener living and software applications. So it sounds like something great, right? Awesome, but how would you go about using gamification techniques and how do you design for such game-like experiences?

One size fits all: badges, leaderboards and points.

If you own a website then you could integrate game elements into it using what’s known as “instant gamification platforms” provided by vendors such as Bunchball and Badgeville. These gamification platforms provide a kind of one size fits all approach, with a range of game elements available for addition to websites to drive participation and engagement. They provide APIs and components that allow site administrators to reward particular user behaviours such as commenting, registration, purchases, social sharing and taking quizzes with virtual game rewards such as levels, points, achievements or tangible rewards such as special offers and premium content.

(Badges! Points! Leaderboards!)

The problem that can arise with these types of game elements are they are primarily reward based elements that aim to motivate users extrinsically. This kind of design lacks some serious fundamentals elements that makes games fun to play. To understand this further let’s (very) briefly discuss motivation theory. It is generally accepted that there are two types of motivation; extrinsic and intrinsic. Extrinsic motivation occurs when an activity is performed in order to attain some external or separable outcome, such as working harder for a pay rise or to get a promotion. On the other intrinsic motivation occurs when an activity is performed for the internal satisfaction of undertaking the activity itself, such as working for the joy of working. The act of playing a game is generally considered an enjoyable and intrinsically satisfying activity on its own. Therefore the general idea behind gamification is that it attempts to harness this enjoyment and fun that people find from games and use it to frame non-game contexts as game-like in order to make them more enjoyable and motivating also. However problems can arise when rewards are the primary element used in gamification designs, whether they are points, badges or real rewards they are simply promoting extrinsic motivation to complete tasks – write 3 posts to unlock an achievement! And these are the biggest issues with plug and play gamification platforms at the moment, they are primarily reward based with no larger goal or no thought about the challenge involved in the task. There are reasons why this is happening – these types of reward systems are easy and cheap to implement, and can be applied to very quantitative actions that can be easily detected by the system (such as the number of comments posted on a website, whether a user has their twitter account hooked up). However to truly create an engaging gamification experience rewards are simply not enough to satisfy the user. So the question arises, what helps to create a more enjoyable gamification design?

Turning to player enjoyment and motivation to play

If the act of playing a game is generally considered an enjoyable and intrinsically satisfying activity on its own then we should consider what makes it so motivating to play. Ryan et al. hypothesise that games are primarily motivating to the extent that players experience autonomy, competence and relatedness while playing – three basic psychological needs that promote intrinsic motivation. This theory is referred to as Self-Determination Theory.

(Self-Determination Theory)

If the addition of game elements to a non-game context promote play in a similar way to games then supporting these three needs can potentially create a more enjoyable gamification experience. And through this enjoyment, engagement may increase in the non-game context the game elements are being applied to. Autonomy refers to the choices people make and why they make them. When people choose to take on an activity for interest or personal value rather than for rewards or because they are made to do it, then perceived autonomy is high. If gamification is an optional element added to a non-game context that people can choose to engage with then autonomy would be high. Within the gamification design, if players are given the freedom of choice over the sequence of actions they undertake and are not forced to one specific path then autonomy would be high. Competence refers to the ability to optimally challenge people, in games if the controls are intuitive and the tasks within the game provide ongoing optimal challenges and opportunities for positive feedback then competence would be high. Competence relates also to Flow theory a particular theory of motivation proposed by Csíkszentmihályi that describes a mental state of operation where a person is fully and completely immersed in an activity. To promote flow a challenge needs to be provided that is appropriate for the skill level of a person. A challenge too hard and the person may feel anxious and overwhelmed, while a challenge too easy can bore a person.

(The concept of Flow)

Finally, relatedness refers to a person’s connection with others, in a game this may be with computer generated personalities or with other players. The need to interact, be connected to and experience caring for others can be a powerful motivator. If these three elements are considered when designing game elements for non-game contexts, rather than simply falling back to motivation by rewards, then the player might be more engaged with the non-game context.

Where to from here?

There’s so much I haven’t touched on here (e.g. the links between pervasive games and gamification, using gamification to attend to different levels of extrinsic motivation, the importance of creating good mappings between goals and actions of the non-game context and the game goals and actions, and on and on…) however it’s enough hopefully to get you started thinking more about the area. Gamification is a very new field, still being defined with a lot of research possibilities available. As I continue my Phd into this area I’m personally interested in research into the importance of mapping meaningful game actions and goals to the contexts in which they are applied, as well as exploring the promotion of player enjoyment in gamification design to enhance motivation. I aim to adopt a model of player engagement from game theory to aid and inform the design of future gamification designs, in particular for mobile contexts. These guidelines will be evaluated using a number of case studies, the first which looks at turning the daily commute into a game in order to encourage greener transport options. That’s it for now! Quite a long read – if you’ve made it this far then achievement unlocked! (Just kidding). If you have any comments or questions add them below or email me with your thoughts! (Source: Gamasutra)

上一篇:关于游戏故事创作过程的几点思考

闽公网安备35020302001549号

闽公网安备35020302001549号