万字长文,关于用户游戏沉浸设定和关联要素分析,上篇

篇目1,论述基于“流”状态的游戏设计的4大特征

作者:Sean Baron

你本来可能只是打算坐下来玩几分钟游戏;而过了好几个小时后,你才后知后觉地意识到自己正在扮演一个柔术演员的角色,并一直努力地在游戏中获取更高分数。此时的你可能会问自己:时间怎么过得这么快?我是在什么时候沉浸到游戏中?

也许你并未真正沉浸于游戏中,但是如果你认为自己是一名游戏玩家,你便可能已经遇到过类似的情况。而当你面对任何游戏都无法自拔之时,你便深陷这种情形中了。

特别是当你在玩一款优秀的游戏时更能够深刻体会到这种感受。如果游戏开发者能够塑造并添加具有强大用户粘性的设计要素,他们便可能创造出有趣,且畅销的好游戏。

dead space from giantbomb.com

幸运的是,一些心理学家已经察觉并研究了这种能够提高用户粘性的内容;他们甚至为其命名为:认知流。我将在以下内容中详细介绍这种“流”及其四大特征。我将从心理角度阐述每一个特征,并提供给游戏开发者一些重要的建议。

介绍

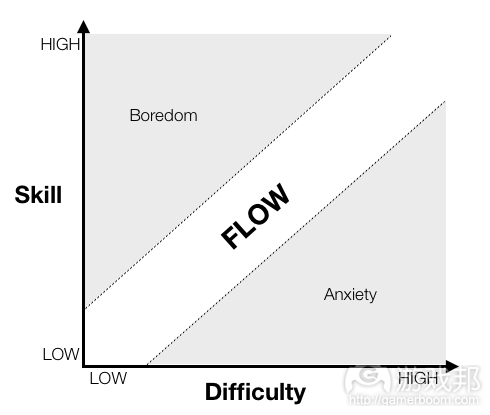

在20世纪70年代,心理学家Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi通过实验发现了“流”的存在。他发现人们的技能以及他们所面对的任务难度将导致不同的认知和情感状态的产生。如果人们的技能太低但却面对过于复杂的任务,他们便会感到焦虑。相反地,如果是技能高超之人面对过于简单的任务,他也会对此感到厌烦。而当人们的技能和任务难度成正比时,他们便会进入“流”状态(见图1)。

figure 1 from gamasutra.com

图1:流,厌烦感和焦虑感都与任务难度和用户技能水平紧密联系在一起。改编自Csikszentmihalyi的研究(1990)。

在这种状态下,人们便会体验到:

1.极度专注于任务。

2.具有主动控制感。

3.整合行动和意识。

4.失去自我意识。

5.忘却了时间的流逝。

6.感受到完成任务是继续前进的唯一方法。

Csikszentmihalyi同样也提到了任务中能够推动技能和任务难度平衡的四大特征(能够提到流状态的概率)。这些特征分别是:

1.拥有明确的目标和管理规则。

2.以个人能力为基准完成目标。

3.明确且即时地反馈执行力和目标完成状况。

4.减少外部干扰,便于集中注意力。

如果游戏开发者希望玩家能够在游戏中产生“流”状态,他们就需要好好研究这四大任务特征。以下我将更加详细地分析这四大特征。

特征1:游戏应该拥有明确的目标和管理规则。

“我完全被搞糊涂了。一个非玩家角色(NPC)告诉我我应该做什么,但是我却因为房间中央的战利品而分神了,并且这时候我还发现了来自四面八方的Giant Spiders。此时我不但不能再访问NPC,我还注意到这个地牢中的所有房间都拥有相同的形状以及相同的颜色,我对此更加迷糊了!我不知道该去哪里也不知道如何才能到达目的地。过了15分钟后我才找到我需要面对的谜题,但是现在我却不知道该使用库存中20个任务道具中的哪一个去揭开谜题。过了一会后,我最终放弃了任务。”

如果玩家不知道目标是什么,不知道自己该如何完成目标或者使用何种技能去解决谜题,他们的“流”状态便会瓦解。并且他们将最终停止游戏。

为何明确的目标和管理规则对于人们来说如此重要?因为我们的信息处理和关注能力都非常局限;我们不可能完全消化所有来自屏幕上或者说话人口中的信息。尽管我们能够同时处理许多基于图像或声音的信息,但是这种处理能力也是非常局限。

特别是当我们的注意力出现分散时,这种处理局限便会更加明显。除此之外,如果任务相关信息过快呈现于人们眼前或者同时展开了多条信息,人们也会明显感受到信息处理的局限性。不管是何种情况,人们都会终止任务的执行。因为此时的人们会充满各种交流,觉得自己不可能完成任务,而因此抑制了内心“流”的发展。

关于信息处理的另外一大重要元素便是确保指示与任务的一致性。如果你能够确保任务和信息/指示保持一致,人们便能够更加容易理解并使用这些信息。

信息处理和注意力问题将直接影响我们解决问题与做决定的能力。如果你的信息处理出了问题,那么人们对于任务目标和规则的理解也会受到牵连。也就是如果人们不能理解问题的本质,他们便会感到焦虑而不愿意去尝试着解决问题。最终,这种挫败感将导致“流”状态的下降并因此影响人们解决问题的能力。

如果面对过多的打击,人们可能会后退求助于他们早前所使用的解决问题方法。但是开发者却不一定能够考虑到这种逆转。

明确目标和管理规则是一种切实可行的方法。获取目标是一种有报答的行为,从而因此能够推动个体继续努力完成目标。不论完成目标能够让你的角色获得升级还是争取更多分数,你都会因此而更加坚定达到目标的最终信念。目标——成就——奖励,如此循环不仅能够让玩家对游戏更加着迷,而且能够推动他们“流”状态的发展。

游戏设计师该如何解决目标和规则问题?如果设计师们能够考虑上述所提到的心理元素,他们便能够轻松地解决这些规则和目标问题。

* 不论是用户界面还是游戏屏幕上的任何内容都应该明确地向玩家指示他们的任务。情境线索,HUD信息以及NPC等也都应该确保目标的浅显易懂。

* 因为注意力的分散会影响理解力,所以设计师应该避免在玩家面对高度刺激感时刻(游戏邦注:如玩家在《光晕2》中面对Flood的肆虐或者在《天际》中需要避开成群的Draugr时)提供目标和指示内容。

* 在提供重要信息时更需要小心谨慎,以此确保信息和任务/目标保持一致。《死亡空间》中的指示线索便是一个典型的例子。开发者通过在玩家所处环境周围覆盖关于下个目标的相关提示,从而让玩家能够清楚地知道自己该如何前进。

* 而关于规则,玩家则希望能够在游戏过程中尝试更多不同的游戏技巧。

但是,在关卡或游戏中间段引入新的机制则会抑制“流”状态的发展。不过有时候这么做却是必要的,并且能够提高游戏的乐趣以及游戏玩法的多元化(例如,在《半条命》中主人公Gordon Freeman第一次获得Zero-point能量场操纵器时)。

但是当你提供新技能给玩家时,你还需要谨慎地面对如何培养他们使用新技能的问题(例如,当Gordon使用Zero-point能量场操纵器去追赶Dog时)的。

* 将小目标(如清除一地的野猪)与更大的目标(如获得足量的XP进行升级)并且与更大的目标(如进入特定关卡的齿轮)相互联系起来。这种联系将创造一系列的奖励体验,从而因此吸引更多玩家玩游戏并构建起“目标——成就——奖励”循环。

如果玩家能够较容易完成目标,他们便更乐意继续游戏。不过就像之前所说的,我们必须平衡玩家技能与任务难度之间的比例。

特征2:游戏只能要求玩家执行自己能力范围内的行动。

“我知道我应该朝着Fiend攻击的相反方向发动进攻,这么做才能够避开他的攻击,并朝着我的相反方向打击他。但是事实上我却做不到这一点。不知道是因为我不够放松还是这是我初次游戏,我的行动都非常笨拙。对此我感到非常沮丧。”

理解玩家的能力局限并培养他们的技能非常重要。如果玩家没有能力完成目标,那么即使你的目标和规则再明确,他们也不会感受到游戏体验的乐趣。

为什么游戏只能要求玩家执行自己能力范围内的行动?

因为如果不这么做,“玩家便会停止游戏!”还有许多心理元素拥有值得借鉴之处:

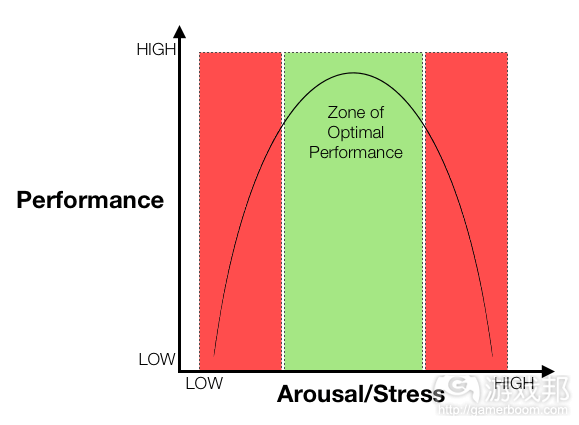

压力和执行力影响着“流”。如果玩家的能力不足以帮助他们完成游戏目标,他们便会倍感压力从而使得自己的执行力大大下降。最终瓦解了他们的“流”状态并破坏了游戏体验的乐趣。

目标难度和玩家的毅力。随着目标难度的提升(与玩家技能紧密相关),玩家关于完成这些目标的耐性也会被慢慢磨平,从而最终不愿意继续游戏。

figure 2 from gamasutra.com

图2:执行力是激励/压力的函数。改编自Yerkes & Dodson法则(游戏邦注:该法则认为压力与业绩之间存在着一种倒U型关系,适度的压力水平能够使业绩达到顶峰状态,过小或过大的压力都会使工作效率降低)(1908)以及Hanin(2007)。

游戏设计师该如何处理涉及玩家技能与任务难度的问题?

每个玩家都拥有自己的执行力-压力曲线(见图2)。这就意味着一名压力值为+7(随机值)的玩家可能拥有非常高的执行力,而另外一名同时拥有+7压力值的玩家就可能就执行力欠佳。

这同样也意味着游戏难度的层次(如简单,中等,困难)设置不合理也会导致糟糕的游戏体验。

游戏开发者应该在游戏中设置能够调整不同游戏情况以适应不同难度的AI,从而对玩家的执行力产生积极的影响(例如《求生之路》系列游戏中的AI Director)。

对于这种AI,你应该着重考虑执行力和乐趣之间的关系。有些玩家在面对越来越困难的任务时执行力也会慢慢提高,但是在这种复杂的挑战下他们却不一定能够感受到游戏的乐趣。在这种情况下,他们反倒会充满焦虑感(如图1所示)。游戏开发者便是从那些拥有较高执行力同时也属于较高流失率玩家中意识到这一点(如,即使玩家因为任务难度的改变而离开游戏,但是他们的执行力却仍保持稳定)。

另外一个需要考虑的元素便是,这些AI该如何针对不同多人玩家团队(如《求生之路2》战役中的4名玩家)设置难度。如此看来,开发者必须深刻意识到任务难度的变化将从不同方面影响着不同能力的玩家。因此,开发者首先需要考虑如何在不破坏游戏的前提下平衡同一个团队中最优秀玩家或最糟糕玩家,从而做出最合理的难度改变。

逐步向玩家传输游戏中的特殊技能。如果你的游戏中没有那些玩家熟知的技能(游戏邦注:如典型的FPS控制或瞄准技能),你就需要逐步地教授玩家你的游戏中的新技能。鉴于之前提到的信息处理局限,你应该让玩家能够在一种相对缓和的环境下学习这种技能。

特征3:游戏应该明确且即时地反馈玩家的执行力

“我这样做对吧?我刚刚创造的斧头是否放置到我的库存中了?这一行动是否能够提高我的魔法能力?”

无论这种反馈信息是基于虚拟高尔夫俱乐部所发出的声音,还是RPG游戏中经典的经验指示栏,或者是FPS游戏中模拟血的红色指示图标,你都需要让玩家清楚自己在游戏中的发展。

为何玩家需要获得即时的反馈?

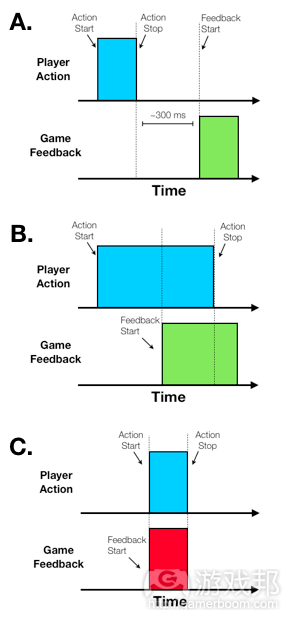

这源自人类与生俱来的学习和调节机制。如果在完成行动后(200至400分毫秒内)或期间给予玩家相关反馈,便能够帮助他们更好地处理行动与结果之间的关系。

但是有趣的是,在行动开始的同时给予反馈信息却不见得有多大成效。(见图3)。

再次回到目标上,如果游戏能够在玩家的游戏进程中提供中期和长期目标(完成一个关卡或完成游戏)反馈,便能够进一步提高游戏的用户粘性并推动玩家最终完成游戏。

这也就意味着接收到反馈信息的玩家更愿意长时间玩游戏。

figure 3 from gamasutra.com

图3:基于玩家行动和游戏反馈之间的合适(A和B)和糟糕(C)的时序设定。

游戏设计师应该如何处理反馈问题?

如果玩家发现行动和结果之间出现了矛盾,他们便很难理解自己的行动对于执行力的影响。

所以开发者应该建立相关机制并尽早呈现给玩家长期和短期目标,随后在整个游戏过程中始终围绕着这些目标而发展。

特征4:游戏应该排除任何会破坏注意力的外部信息。

“这些穿梭于屏幕上方和下方的咒语和图标看起来真有趣!你看我的Ice Storm咒语的粒子影响!等等!谁袭击了我?”

如果面对的是越来越多噪杂的内容,玩家关于察觉并评估重要刺激物的能力便会大大减弱。这就意味着设计师应该确保那些穿梭于游戏中(不论是UI还是HUD)的额外内容足够简单。

为何需要排除任何会破坏玩家注意力的外部信息?

我们不得不再次提到人类对于信息处理的局限:就像我们在第一个特征中所提到的“流”状态,人类对于信息的处理具有一定的局限。而杂乱的视野将会打乱玩家的信息处理过程;并因此影响玩家对于目标和规则的理解,从而最终影响他们的“流”状态。

游戏设计师应该如何处理外部信息问题?HUD和游戏内部的菜单设置便是最简单的方法(游戏邦注:如《死亡空间》或《辐射》中那样)。

如果你的游戏中牵扯到游戏技能或选择,或者说这是开发者为了突破艺术或技术界限所强调的内容,你就必须将其涵括到游戏中去。

结论

能够创造出“流”状态的任务将拥有明确的目标和管理规则;基于玩家的能力调整目标;提供清晰且即时的执行力反馈;并且擅于排除任何外部信息。如果游戏开发者在设计过程中能够考虑这些特征,他们定能够创造出具有较高用户粘性(且高销量)的游戏。

我针对于每个特征所列举出的设计要素只是一种例子;或者说只是基于心理元素的基本原理。你应该根据你所创造的游戏类型——不论简单还是复杂,采用不同方法去应对这些特征和问题——就像每种特征中还存在许多推动着“流”状态发展的心理要素。

同时值得注意的是,大多数优秀的游戏设计师和游戏公司都已经明确(或含蓄)认可了这些“流”特征的重要性。

最后我想说的是,我所提供的这些内容只是引导开发者和设计师思考如何提高游戏的用户粘性;而真正的实践完全取决于那些参与游戏创造的人。

篇目2,关于游戏世界中所呈现的流体验

作者:Neils Clark

注:本文是源自我的博客中的一本书的一个章节。在那本书中这些内容是遵循了有关J.R.R. Tolkien(英国语言学家,作家,创造了《魔戒》三部曲)和逃避主义的内容,并伴随着一个有关沉浸于《Star Wars Galaxies》一年的故事。

在自己的书籍《Flow》中,流理论之父Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi写道:“我们将这种状态称为流体验,因为这是我们所访问过的许多人在自己描述处于最高点的感受时所使用的表达方式‘这就像在漂浮一样,’‘我被流所载着。’”

当我们精通某事,如《Star Wars Galaxies》中潜行追踪Jedi,我们便会有这种感受,然后我们会将这一技能与一些同样让人激动的任务相配对,如同时获得三个Jedi。当我们拥有技能和挑战时,我们会觉得自己非常有能力,而这种感受只停留在当下。我们知道自己应该做什么,但是事情的发展总是太过迅速,从而让我们很容易丢失自我。我们将完全沉浸其中。这是Csikszentmihalyi在工人,CEO,专业运动员,科学家和钢琴家等身上都能发现的一种心理状态。

Star Wars Galaxies(from 52pk)

行动和意识会集中在一起,“当一个人需要使用自己的所有技能去应对某种情境所呈现给他的挑战时,这个人的注意便会完全被该事所吸引。这时候他便不会留下任何多余的心理能量。”我们需要为此投入足够的注意力,如此我们便不会再专注于生活中一些不好的事。如果体验本身也具有意义的话,这便具有双重的作用。

也许这是对于人类来说最具吸引力的体验。不过这有时候也是问题所在。Csikszentmihalyi解释道:

早前的人种志学者认为北美平原的印度人非常沉迷于关于水牛肋骨的赌博,即输者将在寒冷的冬天不穿任何衣服而离开帐篷,同时还要留下他们的武器,马匹和妻子。几乎任何有趣的活动都有可能让人上瘾,比起作为一种有意识的选择,它将成为干扰人类其它活动的必要元素。例如外科医生认为手术就是让人上瘾的,“就像在吸食海洛因一样。”

当一个人非常依赖于控制愉快的活动的能力,即他不能再将注意力放在其它事情上,那么他便算失去了最终的控制力:即决定意识内容的自由。因此能够创造流的有趣的活动也具有潜在的消极面:尽管它们能够通过影响人们的心理而完善他们的生活质量,但是它们会逐渐变成一种瘾性,这时候的人们将完全被俘虏,并且不愿意在应对生活中一些具有分歧的事。

流是非常强大的,所以对于Jane McGonigal在《Reality isBroken》中使用了Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi的理论作为游戏定义的主要支撑我们并不感到惊讶。她称能够理解流的玩家为幸福工程师,这样的流是唯一能够帮助人们解决现实问题的元素。但她同时也清楚游戏的强势,即她描述在一个周末,“我花了24个小时在玩《魔兽世界》,这比我所打算的多了23个小时。我还能说什么呢?在游戏中有太多需要做的事了。”

“当周一早上到来时,我甚至抵抗着回到‘现实’工作中的想法。我知道这并不理性。但我的部分意识一直想要继续赚取经验值,堆积珍宝,收集点数以及完成拯救世界的任务。”

“当然了我最终还是回到了现实工作中。当我花了一点时间去消除想要升级的念头。我的部分意识认为自己在Azeroth王国中所做的事比在现实生活中还多。《魔兽世界》的确提供了非常强大的生产力。它传递的是一连串像毒药一般的任务与奖励。”

“我并不在乎这样的任务并不是真实的。因为对于玩家来说我们所获得的情感奖励是真实的,这才是真正重要的事。”

尽管Jane只提到一个周末,但《Galaxies》却让我迷失了一年。她的书将流描述为游戏让我们感到开心的根本元素。即使流是真正关于幸福,这里仍存在更多情况。有时候游戏将超越“乐趣”,甚至是“吸引人”。

《Galaxies》让我第一次感受到了一种奇怪的状态,即游戏中吸引人的奇怪空间延伸得太长了。不管是因为游戏世界太丰富,或者剩下的世界中的替代选择太可怕,任何世界中的运行能力都开始崩塌了。

Eric Weiner的旅行书《Geography of Bliss》的每一章节都是从这样的标题开始的,即“幸福是……”而书中的每个国家也都有自己引人注意的大标题。如在泰国,幸福是可以抛下烦恼,在摩尔多瓦,幸福是待在任何其它地方。

在今天,幸福似乎是来自电视,杂志以及全新的广告的短暂的承诺。在看了Weiner的书几个小时后,我前往了当地的一家超市并经过了一个写着“这就是幸福的味道!”的冰淇淋蛋糕盒。这便是结构化流—-即专门为我们所设计的流,所以我们可以获得体验然后转身离开,这将遭受到与巧克力蛋糕一样的问题。即巧克力蛋糕只会让我们暂时感到快乐。但是我们并不会每一天每一餐都吃巧克力蛋糕。所以没有实质性的味道便只是在刺激味蕾罢了。

当然了,我也很喜欢蛋糕,但是我不可能吃很多很多。有些游戏会无止境地延续下去。但是我的想法与Jane McGonigal并非完全相同,我并不相信每一款游戏都是基于“真实的人类的需求是真实世界所不能满足的”的理念。与许多艺术一样,游戏体验可能会让我们脱离自己,将我们与之前从未看过的一些很酷的事物联系在一起。在某种程度上,社会组织和高科技都在人类,生物及其无限的人体美之间挖起了一条很深的护城河。

我们从世界那所获得的流与我们自己创造的流之间是具有差别的。首先,体验是由某些人仔细创造并基于适当的安排而给予奖励,所以便能够吸引大众用户的注意。这是基于最少的努力并让我们感觉到对人类来说最强大的体验之一。流只是关于挑战与技能的结合。我们可以在任务一开始(容易学习)或伴随着大量复杂任务(较难精通)的时候感受到它。在这两种情况下,优秀的游戏设计能够保证我们始终都能够获得有关接下来的前进方向或如何更好地应对更大的挑战的提示。这些提示通常都是以奖励的形式呈现出来。

Jane在有关幸福的研究中提到了外在奖励与内在奖励的区别。所谓的外在“美国梦”目标是指:金钱,权利,汽车等等都可以让我们感到不幸福。这也是该研究所要传达的内容。但是奖励,目标以及游戏中基于结构的流等等都是来自外部。它们就像金子,信誉和金钱一样。它们是行走的老虎,是酷炫的喷射式自行车也可以是大胆的裸骑。它们是富丽堂皇的豪宅,是传奇的宝剑,是成就,是明显的技能排行,是显赫的头衔等等能够代表身份的标识。但因为我们仍然对游戏具有根深蒂固的误解,所以我们总是很难看到这些。

在给书命名为“打破现状”的一个大问题便在于它从一开始便明确了“游戏”和“真实生活”之间的二分法。而真正的区别在于什么东西被打破了。如果你们所看到的是有人基于计算机显示器赢得了比赛,那么这可能是本来就设定好的。就像让人们坐着待20个小时的动机便是源自内在。这就像是病理学中的流那样。当你感受到这些世界有多丰富,即关于你将遇到的人,寻找珍宝的乐趣以及无止尽的刷任务,你便会觉得这是一个真实,并不完美,并且多变的地方。我们可以追逐着一些平庸的的现成目标(就像许多人做的那样),我们可以寻找现成的流,我们也可以创造属于我们自己的流,并在这个过程中我们将对自己有更深入的了解。说实话在《Galaxies》中,我们创造了比之后任何在线游戏(包括《魔兽争霸》或《英雄联盟》)中更多属于自己的流,而对于Jane,我也不能去随便评判其书名的真正含义。

自由流—-在聆听了世界和我们自己的想法后,拿Csikszentimihalyi的话来说,我们所创造的流体验是“俗语所说的‘生活的意义是什么?’其实非常简单,生活的意义便在于意义:不管是什么,不管来自哪里,唯一的目的便是带给生活意义的元素。”

如果我们能够在混乱的生活中找到一些“和谐的主题”,我们便能够采取措施在更多地方为自己创造流体验。对于那些创造出自由流,也就是坚持一个目标并塑造自己的技能,同时也会去处理大问题的个人,尽管整个宇宙并不会为之鼓舞,生活仍然很艰难,但是他们有可能带给自己一个最强大的礼物,即目的。

我们总是很容易依赖于那些能够往我们的娱乐,工作或生活中添加吸引人元素的专家们。我们可能会收到更多鼓舞而去从事某种工作,并过着某种生活。但是我们可能不会注意到我们可以更加热爱我们所面对的世界,它可以拥有更多的含义,我们也可以为其创造出流。

游戏并不是幸福的自动导航仪。可以说并不存在这样的导航仪。它们将通过提供基本的比较对象而揭露生活。就像一条鱼也只会在你将其带出水面时才会知道自己其实一直待在水里。《Galaxies》也是如此。它将我带到了一个丰富的世界,这里有着各自奇怪的生物,还有一些由各种人,也包含我在现实生活中仍充满尊敬的人所组成的社区。对于我这种一直待在Gig Harbor的人来说这并不是一个闪耀的黄金时代,但它也并未完全丧失其价值。即使没有任何所谓的“体验语言”,我也能够了解到一些有关乐趣和无聊的刷任务等事情。

Wrote Weiner所说的:“有些读者想要知道他们是否应该搬到像冰岛或不丹等让人开心的国度。也许那是你的心所向往的地方,但真正重要的并不是我们搬到哪里,而是我们能够让这些地方真正走进我们心里。”

“我相信这也适用于任何地理上的变动。改变你的位置的同时你也需要改变自己。并不是说遥远的领土就包含了一些特别的‘能量’或那边的居民拥有一些我们所不知道的知识,但对我们来说更加重要的是:通过迁移,重新定位,我们能够松开期望的枷锁。漂泊到不同地方的我们应该将自己也变成不同的人。”

篇目3,分析游戏沉浸式体验的五大设计元素

作者:Geoff Howland

如何让游戏更加令人上瘾?我们需要有一个驱动力促使玩家愿意沉浸于游戏中。这其中包括:玩家如何完成游戏,与其他玩家竞争,掌握游戏的控制以及界面,探索游戏,获得高分或者赢得同等奖励。

完成任务的沉浸感

完成任务的沉浸感经常依赖于玩家是否愿意看到游戏结果或者只是单纯地希望完成游戏。如果玩家只是想完成游戏的话,那么游戏对于他们来说就是一种挑战。如果玩家接触的是特别复杂的游戏,那么在他们完成游戏之前都会感受到一种成就感。但是并不是都会出现好结果,虽然有些人会认为这是一种挑战而努力去赢取游戏,但是也有些人会认为太困难而中途放弃游戏。人们都喜欢胜利,所以如果你能够提供给玩家一款富有挑战并又能够使他们最终获取胜利的游戏,那么这便是最完美的结果。但是这仅是其中一种设计选择,你应该根据目标用户而做出适当的决策。

如果玩家想通过完成游戏而了解游戏的整体发展,那么这里便需要一定的故事动机。甚至在一些拥有简单故事情节的游戏,如《超级马里奥》也有结果。很多玩家都希望能够在完成游戏后有所收获,并最后拯救出公主。但是一旦玩家知道了游戏故事的结局,而游戏又开始从第一个关卡循环播放,那么很多玩家便会因为掌握了游戏故事而退出游戏。

super-mario(from fanpop.com)

竞争的沉浸感

竞争的沉浸感非常重要,它可以有利地推动并保持游戏长期受欢迎。如果一款游戏能够让2名以上的玩家相互竞争,那么这款游戏有可能会比它的平台或者是硬盘驱动器的还长寿。竞争是电脑游戏的一大基础。在竞争模式下,玩家间能够在游戏规则的监督下按照一种常规模式相互影响,并且游戏的控制权从开发者转移到了玩家身上。玩家可以自己在游戏中设置陷阱,并让其他玩家上当,而且我们常常不能够猜到每个玩家的真正想法。如果你所创造的游戏带有一些较为灵活的规则,那么你也可以让你的玩家自行创造游戏风格,即不约束玩家的移动和所采取的任何战术。

控制权的沉浸感

关于游戏控制权的沉浸感也非常重要。特别是汽车模拟游戏把这种机制当成游戏的首要目标,并模拟特定汽车的相关控制。玩家总是希望能够在赢得一款游戏后,继续玩游戏而完善并提高自己的游戏技巧。而如何才能为他们创造这种游戏界面?你可以在控制器中分设多个细分关卡。举个例子来说,在赛车游戏中,当玩家加速转弯时必须能够深切感受到地面摩擦以及轮胎失去牵引力的感受。你可以通过提供给玩家游戏反馈而帮助他们更好地了解游戏的相关控制。通过音效预示轮胎什么时候开始失去牵引力,以及在转弯的时候引擎发生了何种变化。等等的这些都能够帮助玩家更好地理解游戏是如何运作,从而了解游戏界面并有动力去掌握更多的游戏机制。如果游戏不能提供给玩家足够的反馈信息,或者游戏界面太模糊难懂,那么玩家便很难获得游戏的控制权;如果游戏初学者和高级玩家在游戏中所获得的机会相差无几,那肯定没有人愿意累得半死去成为所谓的高级玩家吧。

探索的沉浸感

探索的沉浸式游戏在很早之前就已经进入电脑游戏领域了。事实上,早前许多游戏都是属于探索类游戏。游戏冒险是指在一种文本游戏中玩家可以在一些区域里游荡,寻找并收集道具,解决一些谜题从而打开更多新的区域进行更深入的探索。《神秘岛》这款游戏也沿用了这种模式,并且取得了不错的销量。《神秘岛》所取得的成绩离不开游戏所采用的模式,即让玩家能够在游戏中探索更多有趣的地方,而不是将游戏局限于一块特定区域。其它游戏如《大魔域》以及《Infocom》冒险系列游戏同样也是基于这种模式,所以很明显这是许多游戏所依赖的一特定流派,不容轻易被忽视。

秘密关卡也是许多游戏不可小觑的重要部分,从《超级马里奥》到《最终幻想7》,游戏沉浸感的一个关键点便是玩家可以在游戏中找到一些秘密关卡。宫本茂(游戏邦注:任天堂的设计师,曾开发了《超级马里奥》,《塞尔达》以及《银河战士》等)曾经说过,在视频游戏中,至少有40%的关卡需要对玩家隐秘,而他确实也在自己的游戏中实践了这一点。

获得高分的沉浸感

获得高分或者打败高分者分为两类,而且都很重要。一般来说,那些想要在电脑游戏中获得高分的行为一方面可能是想要打败其他玩家的分数,另一方面可能是想要精通游戏。所以说大多数游戏博弈的结果都是一个玩家打败了另一个玩家。这种机制最初来自于弹珠游戏,并且仍然适用于今天网络上一些更为先进的游戏。如果你还不知道如何玩这类型游戏,那么你可以先尝试着了解它们的游戏机制,可以说它们已经获得了很大的知名度,甚至创造了一种属于自己的亚文化了。

关于高分沉浸感的另外一种类别便是赢得游戏,而不只是简单地完成游戏。在《超级马里奥》中,当你赢得一个关卡后可以继续挑战更高难度的关卡。对于某些玩家来说在一定时间内多次赢得游戏或者没有任何牺牲顺利完成游戏都是一种自豪的表现。有时候,玩家间会以一段时间为期限比赛谁能够最快赢得《塞尔达传奇》。随着不同玩家间的竞争这种沉浸感也会有所不同,并且最终都能够帮助玩家更好地掌握游戏。

让玩家即使赢得游戏也愿意继续玩游戏,通过添加一些更复杂的机制而推动玩家继续挑战也是增强游戏沉浸感的另外一种方法。

篇目4,故事元素在用户游戏沉浸中的效能分析

不管近的远的总能时时听到一些消息:A先生从某游戏大公司离职聚拢了三五个人开始了游戏创业生涯,而B先生则干脆从不沾边的领域大跨步迈入游戏产业也试图从顺势而为中瓜分自己的市场(特别是社交游戏和手机游戏的前期表现前所未有地降低了游戏研发的准入门槛,并且存在个人或者超小团体以创意的名义几乎颠覆了游戏的概念市场更是让整个游戏产业的制作趋于疯狂)。

.jpg)

addictive(from gamasutra)

有时候我们总是在想,这究竟是游戏市场规模大到随便一个群体(不管是不是标准的开发者)的任何一个探试都能轻易地切割到让各方满意的蛋糕亦或者游戏市场有着各种低成本的试错机会(比如研发经费不高,用户获得成本在可控范围)还是只是单纯地以少数几个基点(比如相对成功的开发者)为核准不断自我放大陶醉的媒介狂欢?

这样的问题多少难以回答,慢慢分不清楚到底是游戏市场的召唤力大到不可抗拒还是什么都不能阻挡开发者一颗从游戏中刨出金砖的决心(不管是模糊地看到别人的成功方向,还是觉得自己有挖掘不完的工作激情)。已经没有办法考量这算不算是一种神奇,看到了别人成功的身影就觉得沿袭很靠谱或者一个灵光闪现的想法就足够当成一根救赎的稻草,短时间内果断作出研发拍板,外表上干劲十足得让人艳羡。然后成千上万的开发者就奔上了市场暂时容量有限的独木桥,我们时常能够私底下看到各种开发者以不同的方式仆倒在盲目向前的路上(绝对大概率事件)但瞬间有人偶尔成功的消息又被当作典范偶像一般的歌颂马上以欢乐和朝气盖过了一路上所有的辛酸、失意和落魄,没有人有冷静反思的空间,看到后来者黑压压的人群和一脸庞的激动自信劲,任何的疑惑一下子就被遗忘殆尽,所有人又信心满满奔袭在疑似康庄大道上。

这种注定路途坎坷恶劣的丛林竞争,大部分的开发者在只是模糊辨识了一点方向就基本什么都不携带地上路了。

这让我想起了David Jones(侠盗猎车手)在谈开发者应该以什么样的态度来审慎对待自己创意设想的问题(开发者需要在投入研发以前先仔细考虑产品寿命和受众价值,如果自己四五个月后就忘了某个游戏理念就最好不要去开发这个理念,而如果两年后仍然对这个想法念念不忘并且满怀激情,那么他就知道这个想法已经成熟,可以将其转变成产品了)和现今阶段的一个比照(要么翻版或者拼凑现有相对有市场的产品设想,要么抱着自己一个拍脑袋得来的想法就果断做产品研发)就必然很清楚失败为什么总是能在最后作为一个大概率事件呈现。而其中最不能略省的就是开发者对自己想做的事情不够明朗(比如只是大体上模糊地知道自己差不多该做什么),这和我早先阅读Tess Jones做游戏和电影比照的时候有太多相似的地方,Tess Jones认为电影脚本需要一个相当严厉的制作、审核和考评过程(甚至需要介入大量的观众喜好元素,即便如此也不一定能够获得拍摄的机会)而现在基本处于大跃进状态的游戏研发(特别是以社交游戏和手机游戏为典型的轻游戏更是如此)在题材遴选和脚本撰写层面则明显不负责任许多(当然和成本投入有关,但更多呈现的是盲然和不专业性,只凭喜好和随时可能熄灭的所谓热情,随时上马一个新项目或者终止一个研发中的项目),同样在其他的附属层面也明显缺失整体考量的拼凑居多(比如声效和背景乐基本在游戏中是独立游离的,很少有能够自始至终将听觉感触当成游戏完整的组成环节)。因为门槛低的缘故,很多明显的瑕疵最后都被市场大潮表面冲刷得一干二净,也鲜少有开发者愿意去回想过去失败的症结,所有人基本都忙着一个事情:我们都处在主动或者被动的大潮中,没有任何片刻停留的心情。

和电影制作相似,好的脚本方案同样是游戏研发的出发点,而这一点在轻游戏的概念中一再被忽视(很多游戏设计基本太慵懒,转而直接借助于现有的方案模板或者进行粗糙换皮或者进行二次整合),鲜少能够为合适且惬意的出发点做探寻,反而是随便一个借力点就出发了,至于究竟能够达到怎样的终点在出发的当刻估计都来不及考虑,所有的一切都急急忙忙,盲目推崇着“唯快不破”的至高理论,以为率先迈出的这一步就一定是赢得未来世界最坚实的筹码。Thomas Grip(Frictional Games)在谈到游戏制作表现力的时候提到了游戏也许也能够追寻电影《辛德勒的名单Schindler’sList》、《肖申克的救赎(The Shawshank Redemption》那般给用户最深处的视听感触,以故事的元素(至少在脚本方案层面下更多的心血而不仅仅只是一个游戏创意的附属,甚至在程序端和美术端能否实现的双重夹击下再度扭曲,更改得面目全非,全然不知道出发点的本意是什么)去引导用户在体验当刻的沉浸(再建一个完整的虚拟世界,并试图让用户忘记除此之外的任何事物)。而这无非和现实人生相似,所有的一切都被切割为碎片再重新拼凑为每一个具有涵义的横断面去支撑玩家在不同时间长度内所能体验的每一个看起来完整的故事(符合逻辑性,比如为了完成一次药材的收集,不同的配方后面都隐含着一个独立而完整的冒险题材,都有着各自惊心动魄的背后故事),没有太明显的中止属性,都能够沿着可选择的方向做不同的延伸(玩家参与了其中的每一个进程,并慢慢对故事的当前状况,过去的脉络和未来的走向有一个概念性的认知,然后以自己已有的知识框架去探寻和验证自己在游戏中的所有的设想)。这也是Ted Price(Insomniac Games)关于用户沉浸理解力的一部分:当开发者的设想框架和玩家真实经历在游戏中逐渐重叠,此时所有玩家之前沉睡于心底的意念就会逐步被唤醒,并开始体现出玩家自己的个体属性来,而这也正是我们所想说的,开发者和玩家两者的共同努力最终赋以了游戏以活的灵魂(共同的呼吸节奏,相互探寻走向和需求,每一次离开都有某种眷念,按照Sean Baron的说法则差不多是这样的:玩家本来可能只是打算稍微体验下游戏消磨时间,可是不知不觉几个小时过去之后才后知后觉地意识到自己正在扮演一个某个游戏角色,并且几乎和这个角色融合到了一起)。

而至于如何将纯粹的理念化归为实际操作,Hidetaka Suehiro(Deadly Premonition,尽管当时这款游戏的骂名居多)将之归结为多个层面:其一是将游戏中的行为与玩家在现实生活中的行为联系起来(在游戏中体现人类的日常需求进而对屏幕外的玩家产生影响,或许还有一些可能某些情节会停留在玩家的脑海不停地徘徊);其二是减少游戏中玩家的受迫感(让玩家在游戏中有自由选择权限而非仅限于任务的强制式);提供给玩家能够区别于其他游戏的印象(比如特征化的角色,经典的对白、游戏角色口头禅或者相对震撼的剧情规划)。Brian Kindregan(StarCraft II)的观点则认为符合逻辑固然是架构故事层面的关键,但是适当和适量的隐秘情节以及一些相应不可预期的游戏机制同样能够挑动玩家对游戏不断的新鲜认知(即所有的环节并不都是能够按照玩家的估算原则走的),吸引人的好故事能够在带入感的感知上演绎出如影视般的视听体验。

当然在可执行的角度上同样存在着如何在操作分寸的可控性,David Jaffe(God of War)认为有些游戏过于着急想展现开发者内心的框架理念,以故事的表现力覆盖了游戏本身必需具备的操作交互属性,诸如在Batman:Arkham City中Bruce Wayne被锁链铐住带往监狱的那段时间就以故事铺垫的名义牺牲了游戏玩法导致玩家在特定的时间内暂时无事可做(如果从游戏的角度而不是影视表现力铺垫的角度,战斗和玩家行为是必须能够尽快获得切换的)。

Ken Levine(Irrational Games)认为这种就必然需要涉及到减少玩家从一个目标向另外一个目标迁移所需要执行的相关步骤(不必像电视台以广告效益考虑所做的剧间强制广告休息,因为玩家在当刻几乎是全神贯注在做一个事情的,没有必要让玩家的思维切换到一个新的事物中,等到差不多时间段内再切回到游戏,这样只能遗失用户对该游戏的专注度)。

另外一种极端就如Erik Wolpaw(Valve Software)所担心的,完全没有必要在游戏中设置一个圆桌任由各种角色围绕期间做各种喋喋不休的高谈阔论(当然没完没了的过场动画也几乎有一样的反面效应)。在国内目前的部分网页游戏中我们是可以这样看的,为了展现战争场面的复杂和壮烈程度,往往对整个战斗需求进行切割(比如同一场战斗又区分为和士兵的战斗、和将领的战斗、和高手的战斗,而每一种类型的兵种可能还可以再区分为若干小种),甚至相似的战斗场面需要经历4至5次以表示足够的繁复(背景相似、声效相似,参与战斗的角色外观上相似,包括数值最后也基本是相似的,这个可以是指多少次技能打击能够击败对手),但是对于玩家而言,这种拖泥带水的表达式则完全违背了开发者设置的初衷而走向反面,我们在舞台剧中所最常看到的一般不是这样呈现的,往往三五个跑腿的小兵即能意指所谓的千军万马而围着舞台简单绕两圈则可能意味着该玩家已经日夜兼程淌过千万重的山山水水了。这里的问题在开发者没有找到合理的思路来处理他们心目中繁复的程式和各种波澜壮阔的画面只能更多借助于重复来进行间接地抒发,以致最终所有的故事模式都有一个基础的模板:来到一个目的地,在这个目的地中参与战斗,征服这个目的地,然后再进入下一个相似的目的地(其实玩家并不完全清楚这些重复的战斗模式对他们能够意味着什么)。所缺少的大概就是Ritesh Khanna(ClipWire)所说的,玩家在游戏中的每一个操作都应该纳入一个具备价值属性的系统,成为一个对后续故事发展有益的筹备,而不仅仅只是一个可有可无的操作指令(或者在当时没能让玩家明白他们操作这一步骤所能够得到的有益价值在后面将呈现为什么)。

有些环节在开发者看来是省时省力且似乎是合情合理的设计,在实际的运作过程中可能会因为出现的高频度而惹恼玩家(玩家在游戏中想体验的并不是一个个只做略微变动的故事内容,他们需要释放更多的故事来满足他们的好奇,而不仅仅只是从换汤不换药的场景换皮),这其中最大的症结仍然是故事叙述不佳,和我们前文所论证的一样,游戏设计的出发点过于自以为是或者过于单薄。Alexis Kennedy(Failbetter Games)认为即便开发者很难从故事框架的角度或者突破,也仍然能够通过以组合的途径或者创造新奇的方式让玩家感受到差异化的体验,诸如在场景中安置一些随机可触发的事件将玩家带入事件模式(哪怕这种事件容量也是单薄的,但终究能够将玩家从寻常的逻辑中岔开,去获得不一样的游戏认知)或者如Vanillaware的Odinsphere将角色与角色之间从剧情层面做串联,在独自完善的同时又给彼此的后续故事留下足够的填补空间或者如Pascal Luban(The Game Design Studio)的建议将影视/小说拓展元素衍化到游戏的表达中(比如使用便捷的方位传送或者自动化传送来改变游戏中冗长到无聊的跑位动作;使用声效特别的变换来唤醒用户对不同环境的辨识)。

而有些游戏事实上也是从相似的角度出发的,诸如Discovery Communications与Hive Medai联合推出的Deadliest Catch: The Social Game(原为获得艾美奖的纪录片连续剧)或者James Patterson以Women’s Murder Club为蓝本推出了Catch a Killer。

篇目5,阐述游戏沉浸感的心理学概念

作者:Jamie Madigan

当我们说到一款好游戏时,我们经常提到“沉浸感”这个词。但它到底是什么意思呢?怎么才能增加游戏沉浸感?问5个人,你可能会得到10种观点,但心理学家早在几十年前就一直在研究各种媒体的沉浸感,所以他们也许能给出这些问题的答案。

只是,他们并不称我们所谓的“沉浸感”为“沉浸感”,他们称之为“临场感”,后者听起来显然不如前者那么酷。至于我们如何感知媒体,研究者已经鉴定了若干种临场感,但我认为最接近玩家所谓的“沉浸感”的是其中的空间临场感。

简单地说,空间临场感通常被定义为“当媒体用户把媒体内容被当作‘真实的’东西来感知时,媒体用户就会感觉自己在空间意义上,置身于这个媒体环境中”;这种感觉就是空间临场感。也就是说,当用户开始感觉自己就是游戏所创造的世界中的“那里”时,游戏(或任何其他媒体,如书籍或电影)就使玩家产生一种空间临场感。处于沉浸感中的人往往只考虑在虚拟世界的情境中是合情合理的选择。例如,沉浸于《荒野大镖客》的玩家更可能选择在游戏中显得合理的旅行方式,如坐驿站的马车,而不是选择菜单栏中的快速旅行,因为后者脱离了游戏情境。对媒体沉浸得越深的玩家就越喜欢前者。

空间临场感(沉浸感)的理论

为什么会这样?那么使玩家觉得自己生存在现实世界背后的游戏怎么样呢?理论是很丰富的,但几年以前,Werner Wirth等研究人员组成的团队已经通过研究总结出一套统一的理论。如下图所示:

Werner_et_al_model(from psychologyofgames)

(看来是相当简单的……)

我们只看与玩家最相关的部分。

基本上,Wirth等人的理念认为,空间临场感的发生要经过三个步骤:

1、玩家在头脑中形成游戏展示给他们的世界或空间的影象。

2、玩家开始以这种基于媒体的空间(游戏世界)作为自己“在”哪里的参考点。

3、获益!

所以,基本上这个过程始于,玩家通过各种线索(例如图像、移动、声音,等等)形成游戏虚拟的空间的心理模型和对他们能感受到的这个世界的假设。一旦对游戏世界的心理模型产生,玩家就必须有意识或无意识地判断,自己是否感觉到自己当前是处于想象中的世界还是真实的世界。当然,值得注意的是,这个判断不一定是有意识的,不一定要经过大脑前额皮质(游戏邦注:前额皮质是决定包括语言、社交行为和决策等复杂思考和行为的关键部分)的作用。玩家可以是无意识地、悄悄地、不断地进入和退出这个心理模型。

研究人员已经对这两个步骤的发生进行广泛的研究,但我认为出于我们的目的,我们不妨直接跳到他们发现的能促进这些步骤产生和创造沉浸感的媒体(游戏)和人(玩家)的特性。

导致空间临场感的游戏特性

促进沉浸感的游戏特性大概可以分成两类:一类负责创造游戏环境的丰富的心理模型,另一类负责创造游戏环境中的事物之间的一致性。

我们先理解一下所谓的“丰富”的概念。以下几点虽不详细,但都与“丰富”有关:

1、感觉信息的渠道多

2、感觉信息的完整

3、对认知要求高的环境

4、生动的和有趣的叙述、情节或故事。

“感觉信息的渠道多”意味着感官信息的生效是一前一后的,联系得非常紧密,在这种情况下,沉浸感就会更强。例如,一只鸟飞过头顶,很好;如果能听到它的叫声就更好了。在这里,3D可能也有重要作用,我们都知道视觉革命是空间临场感的新时代的先导。

red dead redemption(from psychologyofgames)

(《荒野大镖客》具有很强的沉浸感,部分是因为许多东西都是紧密地生效的,不需要玩家费太多想象力去填补空隙。)

“感觉信息的完整”意味着玩家对游戏世界形成的心理模型是非常完整的,没有太多需要玩家填补的空白。抽象和自圆其说(例如,玩家看到小镇里一个人也没有,就猜想是因为瘟疫)是沉浸感的大敌。《刺客信条2》的沉浸感很强,是因为它的小镇到处是人,而且这些人都在做着真正的人会做的事。熟悉的环境使玩家可以轻松地填补空白,而不需要跳出游戏世界思考。很多人都知道西大荒是什么样的,《荒野大镖客》以它为原型构建世界,极大地促进临场沉浸感。

“对认知要求高的环境”是指,玩家必须运用大量脑力资源来专注于游戏中发生的事。这对强化沉浸感是非常有益的,因为如果玩家的脑力都被分配给理解或探索游戏世界,那么玩家就不太会注意到游戏世界中可能让他们意识到“你是在玩游戏”的问题或缺陷。

最后,你会一直被“生动的和有趣的叙述、情节或故事”吸引着。事实上,这是书本创造沉浸感的唯一工具,而它对游戏也适用。好的故事除了把玩家的注意力吸引到游戏中,使游戏世界显得更加可信,也占用脑力资源。

说到与“一致性”有关的游戏特性,我们有:

1、游戏世界中没有不协调的视觉线索

2、游戏世界中的行为是始终如一的

3、游戏世界的表现是完整的

4、与游戏世界的物品产生互动作用

“游戏世界中没有不协调的视觉线索”是另一个促成空间临场感的前提。如果我们讨论电影中的这个概念,我会举这样的一个例子:原本可信的场景中突然出现一个长杆话筒。这就必然使观众反应过来“哦,这只是游戏。”不和谐的东西还包括HUD、教程信息、敌人头顶上出现的伤害数值、成就提示、好友通知,等等。这就是为什么游戏内置广告对沉浸感的破坏那么大——看电影时,如果你发现Adam Sandlar的电影中植入25个广告,你还会专心想象你正在努力拯救人质吗?

bioshock_audio_diary(from psychologyofgames)

(严肃地说,谁会使用这种东西来做录音日记?)

“游戏世界中的行为是始终如一的”意味着,游戏世界中的角色、物品和其他东西的行为正如你所希望的那样发生。值得强调的另一点是,这些线索在整个体验中必须是合理的、一致的。这是为什么我会认为《生化奇兵》的录音日记破坏了原本非常强的沉浸感:谁会记录声音日记,把它分成20段,放在专用的磁带放音机里,然后叫玩家去各种公共场的角落里找这些片段呢?这不科学。

“游戏世界的表现是完整的”是指,关于你的游戏创造的虚拟世界的空间线索不能突然出现又突然消失。这正是每一次玩家看到加载页面、教程或游戏菜单时出现的事。当这种事发生时,游戏世界简单就是消失了,而我们是不可能对不存在的东西产生沉浸感的。

“与游戏世界的物品产生互动作用”大概与上述的“丰富”类似,但我把它归类到“一致性”中,是因为它是给予玩家行动反馈的另一种方式,让玩家感觉环境的各个部分之间具有一致性。操作机器、与NPC对话和物理现象都使玩家觉得游戏世界的各个部分是紧密结合在一起的。

oblivion(from psychologyofgames)

(《湮灭》和《辐射3》具有很强的沉浸感是因为它们允许玩家与几乎所有东西产生互动作用。)

导致空间临场感的玩家特性

当然,玩家本身对其是否沉浸于游戏也是有一定影响的。有些人的空间能力就是更强,可以更快地形成更加生动的心理模型。研究人员发现,那些具有“全神贯注”特点的人能更快对某物着迷。

有时候玩家会产生主动的作用。有些玩家就是想相信幻觉,把自己的偏见导向接受“我就在那里”的假设。在这种状态下,他们会需要更少的证实信息来接受假设,更少的反驳信息来拒绝假设。这类似于“姑且相信”,也就是玩家为了好好玩游戏,主动忽略不合理的东西(游戏邦注:如打了敌方战士那么多子弹,对方居然还不死)。

其他研究人员还指出他们所谓的“介入感”的概念,它是指媒体用户渴望在信以为真的世界中活动,使之与自己的生活保持平行关系,根据他们自己的设计影响变化。对我而言,这似乎是对“有些人喜欢角色扮演”的过度说法,这会直接导致更深的沉浸感。

任何玩家都可以举出突然中断他们的沉浸感的例子。心理学家已经研究、分类了很多例子。但这不是说,所有游戏都应该力求沉浸感。我认为在所有媒体中,游戏是独一无二的。没有沉浸感,游戏仍然可能是好游戏,有些游戏甚至因为没有沉浸感才成为好游戏。但这是件好事,意味着游戏设计师可以用很多种方式来创造优秀的艺术品。

篇目1,篇目2,篇目3,篇目4,篇目5(本文由游戏邦编译,转载请注明来源,或咨询微信zhengjintiao)

篇目1,Cognitive Flow: The Psychology of Great Game Design

by Sean Baron

You sit down, ready to get in a few minutes of gaming. Hours pass and you suddenly become aware that you’re making ridiculous faces and moving like a contortionist while trying to reach that new high score. You ask yourself: Where did the time go? When did I sprain my ankle?

Maybe you didn’t sprain your ankle, but if you consider yourself a gamer, you’ve probably ended up in similar situations. They happen because you’ve reached a critical level of engagement with whatever game you’re playing.

More often than not, these types of gaming sessions occur when you’re playing a great game. If game developers were able to characterize and add design considerations that facilitate these engaged states they’d create more enjoyable and better selling games.

Luckily, these heightened levels of engagement have been studied by psychologists. They even have a name for it: Cognitive Flow. In what follows, I will introduce Flow and the four characteristics of tasks that promote it. For each characteristic, I will provide some basic psychological perspectives and relevant recommendations for game developers.

Introduction

In the 1970s a psychologist named Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi experimentally evaluated Flow. He found that a person’s skill and the difficulty of a task interact to result in different cognitive and emotional states. When skill is too low and the task too hard, people become anxious. Alternatively, if the task is too easy and skill too high, people become bored. However, when skill and difficulty are roughly proportional, people enter Flow states (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Flow, boredom, and anxiety as they relate to task difficulty and user skill level. Adapted from Csikszentmihalyi, 1990.

While in these states, people experience:

1.Extreme focus on a task.

2.A sense of active control.

3.Merging of action and awareness.

4.Loss of self-awareness.

5.Distortion of the experience of time.

6.The experience of the task being the only necessary justification for continuing it.

Csikszentmihalyi also outlined four characteristics found in tasks that drive an equilibrium between skill and difficulty, thus increasing the probability of Flow states. Specifically, these are tasks that:

1.Have concrete goals with manageable rules.

2.Demand actions to achieve goals that fit within the person’s capabilities.

3.Have clear and timely feedback on performance and goal accomplishment.

4.Diminish extraneous distraction, thus facilitating concentration.

It is these four task characteristics that game developers should consider if they want to increase the likelihood of causing Flow states in gamers playing their games. I will now go into more detail about each characteristic.

Characteristic 1: Games should have concrete goals with manageable rules.

I’m lost. An NPC just told me what I was supposed to do, but I was distracted by the loot in the middle of the room and the Giant Spiders coming at me from all directions. It doesn’t help that that I can’t access the NPC anymore, or that all of the rooms in this dungeon are the same shape and color. Lost. I have no idea where to go or how I’m supposed to get there. Fifteen minutes pass before I find the puzzle I need to complete. But now I have no idea which of the 20 quest items in my inventory I should use to solve it. After a while, I give up in frustration.

Flow breaks down when a player doesn’t know what their goals are, how they’re expected to accomplish them, or which new game techniques they’re supposed to use to solve a puzzle. When this happens, gamers disengage and are more likely to stop playing.

Why do people need concrete goals and manageable rules?

We have limits on our information processing and attentional capabilities. Not all of the information coming from the screen or out of the speakers gets processed. While we are capable of handling a lot of visual and auditory information at one time, we do have limitations.

Critical processing restrictions occur when our attention is divided. This can happen when task-relevant information is presented too quickly or when multiple sources of stimulation are competing for our attention. In either case, task performance can drop dramatically. When this happens, people become anxious about accomplishing their goals, thus inhibiting Flow.

Another aspect of information processing that can be overlooked is the congruency between directions and task. People are best able to understand and apply relevant information to a task when there is congruency between the task and the information/instructions.

Our ability to problem solve and make decisions is directly affected by information processing and attentional issues. When there are breakdowns in information processing, comprehension of task goals and rules also suffers. If people do not understand the nature of a problem, they can become frustrated attempting to solve it. These peaks in frustration decrease Flow and also affect problem-solving techniques.

When overwhelmed with too much stimulation, people will often revert to methods of problem solving that have worked in the past. These reversions may or may not be what the developers had in mind.

Concrete goals with manageable rules are achievable. The act of achieving goals is rewarding and reinforces actions that allow individuals to continue completing goals. Whether it’s leveling your character or earning points for head-shots, the very act of accomplishing something reinforces your desire to keep accomplishing. This goal-achievement-reward cycle can keep gamers glued to a game and facilitates Flow states.

How can game designers fix problems with goals and rules?

If designers are able to take into account the psychological factors mentioned above, they can easily address issues with rules and goals.

Everything from the user interface to the play screen should clearly direct or cue the gamer to their task. Situational cues, HUD information, NPCs, etc. should make goals plainly comprehensible.

Because divided attention hurts comprehension, goals and directions should not be given to a player during high-stimulation times (e.g., while a player is fighting an infestation of the Flood in Halo 2 or fending off hordes of Draugr in Skyrim).

Care must be taken to provide important information so that congruency between the information and the task/goal is achieved. The directional cues used in Dead Space are a wonderful example of this. By overlaying an illuminating path to the next objective on the player’s immediate surroundings, the developers left no ambiguity regarding where to navigate.

Regarding rules, the gamer may be expected to try new variations of gameplay techniques developed throughout the game.

However, introducing new mechanics mid-level or mid-game may inhibit Flow. Sometimes this is necessary and leads to increasingly fun and dynamic game-play (e.g., when Gordon Freeman is first given the Zero-point energy field manipulator in Half-Life 2).

When this happens care should be taken to train the player on new skills (e.g., when Gordon used the Zero-point energy field manipulator to play catch with Dog).

The completion of small goals (e.g., clearing a field of boars) links to larger goals (e.g., getting enough XP to level up), which in turn link to even larger goals (e.g., getting access to level-specific gear). This linkage creates a series of rewarding experiences that can hook gamers to a game and create the goal-achievement-reward cycle.

If players are readily able to accomplish goals, they are more likely to continue playing. Though, as previously mentioned, there must be a balance between the player’s skill and the difficulty of task.

Characteristic 2: Games should only demand actions that fit within a player’s capabilities.

I know I’m supposed to swipe in the opposite direction of the Fiend’s attack. This should parry his attack, opening him up for my own counter. But I just can’t do it. Whether it is lack of reflexes, or the fact that I just started playing the game, I’m hopelessly inept. I’m also seriously frustrated.

Understanding the limits of player ability and cultivating player skill is of critical importance. If players are unable to accomplish goals — even if goals and rules are clear — then they will find their gaming experience dissatisfying.

Why should games only demand actions that fit within a player’s capabilities?

Even beyond the obvious answer — “Because players will stop playing!” — there exist many psychologically based considerations worth enumerating. Here are a couple of them:

Stress and performance affect Flow. If a player isn’t skilled or capable enough to accomplish game-based goals, they may experience stress-provoking drops in performance. This kills Flow states and drives down the overall enjoyment of the gaming experience.

Goal difficulty and player perseverance. As goals become increasingly difficult to accomplish (in relation to player skill), commitment to accomplishing these goals diminishes. If this happens, a gamer is very likely to simply stop playing.

Figure 2: Performance as a function of Arousal/Stress. Adapted from Yerkes & Dodson, 1908, and Hanin, 2007.

How can game designers fix problems related to skill and difficulty?

Each gamer has a unique performance-stress curve (see Figure 2). This means that for some people +7 stress (an arbitrary value) causes them to operate at their highest level of performance, but for a different person +7 stress results in them failing spectacularly.

This also means that coarse gradations of game difficulty (e.g., Easy, Normal, Hard) may not lead to an optimal experience for many gamers.

Game developers could include AI that are able to dynamically adjust the in-game conditions affecting difficulty, thus positively affecting player performance (e.g., the AI Director in the Left4Dead series).

One critical consideration for such an AI is the relationship between performance and enjoyment. Some players may perform extremely well when dynamic difficulty is increased; however, they may not enjoy being under such high levels of challenge. In this case, they may feel anxiety (e.g., Fig. 1). Game developers could identify this by marking players who have high performance and high quit-rates (i.e. the player quits in response to changes in difficulty, but their performance remains steady).

Another consideration is how these AI handle difficulty for multiplayer teams (e.g., four players in a Left4Dead 2 campaign). In these cases it is important to recognize that dynamic changes to difficulty may affect players of varying ability in different ways. Thus, it is crucial to determine how to optimally change difficulty without ruining the game for very good or very bad players on the same team.

Certain game-specific skills must be slowly taught to players. If a game does not leverage skills commonly used in gaming (e.g., typical FPS controls and aiming), players must be gradually taught the new game-specific skills. Because of previously mentioned information processing restrictions, this sort of in-game training should occur in a relatively subdued environment.

Characteristic 3: Games should give clear and timely feedback on player performance.

I did that right, right? Is the axe I just made actually in my inventory? Is this action adding to my enchantment abilities?

Whether the feedback is in the form of sound coming off of a virtual golf club, the omnipresent experience bar in an RPG, or the flash of red simulated blood in the vision of a FPS avatar, players need to know how they’re doing.

Why do gamers need timely feedback?

Our innate learning and conditioning mechanisms. Feedback that occurs directly after (200 to 400 millseconds) or midway through the completion of an action leads to the formation of the strongest associations between action and outcome.

Interestingly, simultaneous timing of feedback with the onset of an action does a poor job of facilitating associations. (See Figure 3).

Back to goals… For medium and long-term goals (completing a level, or the game) feedback on progress can drive further engagement and eventual accomplishment.

This means that players who get feedback will want to play more.

Figure 3: Examples of good (A and B) and bad (C) timing between player action and game feedback.

How can game designers address feedback concerns?

If designers want to create lasting connections between a gamer’s actions and the outcomes within the game, they must be sensitive to the timing issues mentioned above (and in Fig. 3).

If there is a critical disconnect between an action and an outcome the gamer will fail to understand how their action affected their in-game performance.

Establish mechanisms and displays of both long-term and short-term goal accomplishment early on, and then maintain these throughout the game.

Characteristic 4: Games should remove any extraneous information that inhibits concentration.

These animated spell and item icons across the bottom and top of my screen sure look cool! See the particle effects on my Ice Storm spell… Wait — is someone attacking me?

As sensory and informational clutter increases, the gamer’s ability to find and evaluate important stimuli diminishes greatly. This means that designers should strive to maintain a level of simplicity across all aspects of their games (from UI to HUDs).

Why do gamers need extraneous information to be removed?

Again, there are inherent limitations on how much information we can parse at any moment: As detailed in the discussion about the first characteristics of tasks that invoke Flow, we are limited in how much information we can process. Cluttered visual fields disrupt information processing. These disruptions can then negatively affect goal comprehension and rule learning, which ultimately affects Flow.

How can game designers address extraneous information? HUDs and in-game menus should be as simple as possible (e.g., Dead Space or Fallout).

Game skills or options should only be included if they are relevant to the story of the game or are purposefully being used by the developer to push artistic and technical boundaries.

Conclusion

Tasks that induce Flow states tend to have concrete goals with manageable rules, goals that fit player capabilities, clear and timely feedback on performance, and are good at eliminating distractions. If game developers are able to include design considerations that take these characteristics into account they will drastically improve player engagement (and likely game sales).

The example design considerations that I provided for each characteristic are just that: examples. The same can be said for the psychologically-based rationales I provided. Depending on the type of game a developer is making, and whether it is high- or low-concept, different ways of addressing these characteristics are eminently possible — just as there are many more psychological factors driving how each characteristic contributes to Flow.

It’s also worth noting that, for the most part, good game designers and good game companies are already explicitly (or implicitly) taking these Flow characteristics into account.

In the end, I only hope to provide developers and designers with some food for thought on improving player engagement. It is up to those involved in creating games to decide how best to apply this information.

篇目2,Flow

by Neils Clark

Some notes: this comes from a book chapter you can find on my personal blog. In the book this stuff follows other stuff (posted here at Gama) about J.R.R. Tolkien and Escapism, and occurs alongside a personal story about vanishing into Star Wars Galaxies for a year.

–

In his book Flow, father of flow theory Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi writes, “We have called this state the flow experience, because this is the term of many of the people we interviewed had used in their descriptions of how it felt to be in top form: ‘It was like floating,’ ‘I was carried on by the flow.’”

We get there once we’ve mastered something, say, Stalking Jedi in Star Wars Galaxies, and then matched that mastery to some equally breathtaking quest, say Take Three Jedi Masters at Once. When we have the skills, and the challenge, we can feel utterly competent, and in the moment. We know what we’re supposed to do, but things are happening so fast that we lose track of our own selves. We’re completely invested. It was a state of mind that Csikszentmihalyi observed in factory workers, CEOs, professional athletes, scientists, pianists.

Action and awareness come together, “When all a person’s relevant skills are needed to cope with the challenges of a situation, that person’s attention is completely absorbed by the activity. There is no excess psychic energy left over.” It takes enough of our attention that we can’t focus on the bad shit in life. It’s a double whammy, if the experience itself can also be involving and meaningful.

It is, perhaps, the most engaging experience available to humankind. Which can on occasion be a problem. Csikszentmihalyi explains,

Early ethnographers have described North American Plains Indians so hypnotically involved in gambling with buffalo rib bones that losers would often leave the tepee without clothes in the dead of winter, having wagered away their weapons, horses, and wives as well. Almost any enjoyable activity can become addictive, in the sense that instead of being a conscious choice, it becomes a necessity that interferes with other activities. Surgeons, for instance, describe operations as being addictive, “like taking heroin.”

When a person becomes so dependent on the ability to control an enjoyable activity that he cannot pay attention to anything else, then he loses the ultimate control: the freedom to determine the content of consciousness. Thus enjoyable activities that produce flow have a potentially negative aspect: while they are capable of improving the quality of existence by creating order in the mind, they can become addictive, at which point the self becomes captive of a certain kind of order, and is then unwilling to cope with the ambiguities of life.

Flow is powerful, so it’s no surprise that in her Reality is Broken, Jane McGonigal uses Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi’s theory as a major pillar for her definition of games. She calls the gamers who understand flow Happiness Engineers, saying they’re uniquely positioned to help fix reality. But she too seems aware of gaming’s potential to overwhelm, describing a weekend where she, “…spent twenty-four hours playing WoW – which was about twenty-three more hours than I’d intended. What can I say? There was a LOT of world-saving work to do.

“… When Monday morning came around, I resisted the idea of going back to ‘real’ work. I knew this wasn’t rational. But some part of me wanted to keep earning experience points, stacking up treasure, collecting my plus-ones, and checking off world-saving quests from my to-do list.

“…I did go back to real work, of course. But it took me awhile to shake the feeling that I’d rather be leveling up. Part of me felt like I was accomplishing more in the Kingdom of Azeroth than I was in real life. And that’s exactly the IV drip of productivity that World of Warcraft is so good at providing. It delivers a stream of work and reward as reliably as a morphine drip line.

“…and it doesn’t matter that the work isn’t real. The emotional rewards are real – and for gamers, that’s what matters.”

While Jane only mentions one weekend of “blissful productivity,” Galaxies had me lost for a year. Her book means to use flow as the foundational evidence that games make us happy. Even if flow was ever really about happiness, there’s more happening here. At some point, games go beyond “fun,” or even “engagement.”

Galaxies gave me a first taste of that strange limbo, the awkward space where engagement stretches too long. Whether because the game world is simply too rich, or the alternatives in the rest of the world too awful, the ability to function in any world starts to corrode.

–

Eric Weiner’s travelogue Geography of Bliss starts every chapter title with, “Happiness is…” And each country gets its own catchy headline. Thailand is, for instance, where Happiness is Not Thinking, and in Moldova, Happiness is Somewhere Else. The former NPR correspondent chuckles at the “self-help industrial complex,” then consults glowing Indian gurus and happiness politicians in Bhutan.

Happiness seems to be the distracted, ephemeral promise of near every television, magazine, and news advertisement out today. A few hours after cracking Weiner’s book open, at the local supermarket I walked by a box for a Snickers-brand ice cream cake with the slogan, “It’s what happiness tastes like!” Structured flow – flow that’s designed for us, so we can take the experience and leave – suffers from the same problem as a chocolate cake. Chocolate cake makes some of us happy, for awhile. But not if we eat it every meal, every day. Flavor without substance is just dumb stimulation.

And sure, I love cake as much as the next guy – probably way more – but I can only eat so much of it. Some games go on indefinitely. Though I haven’t exactly given Jane McGonigal a fair shake yet, I’m not convinced that every game fulfills “…genuine human needs that the real world is currently unable to satisfy.” Like a lot of art, game experiences might take us outside ourselves, connect us with cool shit the likes of which we might never have seen otherwise. If she means the kind of escape Tolkien is talking about, I absolutely agree. To some extent, social organization and high technology have dug some deep moats between the planet’s human beings, her creatures, and her boundless physical beauty. Past that?

There’s a difference between flow that we can take from the world – that we consume like a Hot Pocket – and flow we create. In one, the experience is carefully structured (by someone else) to mete out rewards on just the right schedule, so that a mass audience can detach. So that with minimal effort we can feel one of the most powerful experiences available to humankind. Flow is just a good mix of challenge and skill. We can feel it at the start of a task (easy to learn) or even with the complexity of a massive task (hard to master). In both cases, good game design ensures that we’re always given hints as to where we ought to head next, or just how to better build ourselves up for the larger challenges. Those hints usually come in the form of rewards.

Jane talks about the difference between extrinsic and intrinsic rewards, in the happiness research. That the extrinsic “American Dream” goals: money, power, cars, can go so far as to make us unhappy. That’s certainly in-line what the research suggests. But the rewards, goals, what have you, which evoke the structured flow in games are by and large extrinsic. They’re gold, credits, currency. They’re rideable tigers, floating jet bikes, and other thoroughly pimped rides. They’re palatial mansions on Naboo, legendary swords, achievements, visible skill rankings, visible titles, and all manner of status symbols. That’s hard to see, because we’re still struggling with a more fundamental misconception about games.

The big problem in naming a book “Reality is Broken,” is that it establishes from the outset that false dichotomy between “games” and “real life.” The distinction is what’s broken. If all you can see is someone winning a staring contest with a computer monitor, it might look intrinsic. Like the motivation to sit twenty hours at a time is all coming from within. It looks just as much like flow as it does pathology. When you know how rich these worlds can be, about the people you can meet inside, the treasure troves of fun and the abysmal bullshit grinds, it becomes clear that they’re a place that’s real, imperfect, and changeable as any other geographical subsection of the planet. We can go after trite readymade goals (and many do), we can find readymade flow (and many do), we can also build our own flow, and in so doing learn a thing or two about ourselves (and many do). To be fair to Galaxies, I made a lot more of my own flow there than in later online games, say Warcraft or League of Legends. To be fair to Jane, I can’t be too judgmental where book titles are concerned.

Free flow – flow experiences we build ourselves, after listening to both the world and ourselves – show us that, in Csikszentmihalyi’s words, “…the old riddle “What is the meaning of life?” turns out to be astonishingly simple. The meaning of life is meaning: whatever it is, wherever it comes from, a unified purpose is what gives meaning to life.”

If we can discover some “harmonious theme” to the chaos of our lives, then we can take steps to building for ourselves the experience of flow in more and more places. The individual who embodies free flow – who sticks to a goal, builds their skills, and tackles big problems – the universe might not be there cheering them on, life might be awful, but they have perhaps the most powerful gift an individual can give to themselves: purpose.

It gets really easy to just rely on the experts, who can build engagement into our entertainment, our jobs, our lives. We might get a lot more motivated (intrinsically and extrinsically) to do those jobs, and live those lives. But in so doing we might not notice the worlds we could’ve liked a lot more, which could have meant more, had we been the ones making them flow.

Games aren’t autopilot for happiness. That doesn’t exist. They reveal life by giving it a basis for comparison. A fish doesn’t know it’s in water until you snatch it out. Galaxies did just that. It transported me to rich worlds populated by strange automated creatures, shady guilds composed of shady human beings, and people I’m still grateful to have in my life. It wasn’t exactly a shining golden age for the part of me doing misdeeds in Gig Harbor, but it wasn’t completely bereft of merit. Even without any so-called “experience language” I’d learned – first hand – a few things about fun, and the futility of grinds.

“…some readers wanted to know if they should move to happy places like Iceland or Bhutan.” Wrote Weiner, in his Geography, “Perhaps, if that is where your heart lies, but the point is not necessarily that we move to these places but, rather, that we allow these places to move us.

“I believe, now more than ever, in the transformative promise of geography. Change your location and you just may change yourself. It’s not that distant lands contain some special “energy” or that their inhabitants possess secret knowledge (though they may) but rather something more fundamental: By relocating ourselves, reorienting ourselves, we shake loose the shackles of expectation. Adrift in a different place we give ourselves permission to be different people.”

篇目3,Game Design : The Addiction Element

By Geoff Howland

What makes a game addictive? In order for a game to become addictive there must be a driving force to keep playing the game. Some reasons behind this are: to finish the game, to compete against others, to master the game’s control and interface, to explore the game and getting a high score or equivalent.

Addiction of Finishing the Game

An addiction to finish the game is often based on either wanting to see the end result or just to complete it. In the case of just trying to complete the game it can be seen just as a challenge. A particularly difficult game it may be an act of pride to keep playing until the game is complete. This doesn’t always create the best results though because where some people may find a challenge to win, many others may just find it too difficult and give up. People like to win, if you can provide a game that challenges them and still lets them eventually win you will probably end up with happier players overall. This is a design choice though and needs to be made when your targeting your audience.

In the case where a player finishes a game to see how it ends, there is a story motivation. Even in a game with a simple story such as Super Mario Brothers there was an ending. Many players wanted to find out what happened when they beat the game and eventually rescued the princess. Once they found out the ending and the game started over on the first level again they had finished the story and this is where many people stopped playing the game.

Addiction of Competition

The addiction of competing against others is a powerful one and can keep a game alive and thriving for incredibly long periods of times. A game that two or more players find a good interface to compete through can last far longer than its shelf or hard drive life expectancy. Competition is one of the cornerstones of computer games. It allows people to interact with each other on a common level under the supervision of the game’s rules and really puts the game in the hands of the players, instead of the developer. The players will figure out their own traps and snares for each other and usually far exceed what the developer could think of before hand. If you create your game with flexible rules you can allow players to create their own playing styles, moves and tactics in your games that you had not planned for.

Addiction of Mastery

The addiction of mastery of a game or its control is also extremely powerful. Vehicle simulation games especially show this as their primary goal is to simulate the control of a particular vehicle. Often after a game has been beaten it will still be played to improve and refine the player’s skill. The trick in making a good interface to allow this is to create detail levels in the controls. For example in a driving game a simple turn with maximum efficiency you must be able to feel the road and give when your tires are losing traction. The key to allowing the player to learn your game’s control is in your feedback to the player. A sound signifying the tires beginning to lose traction, the sound of the engine in different states as you are pushing through a turn. Anything the player can use as a map to understanding how the game is functioning will let them grow into an interface and give them a reason to try to master it. If the player does not have enough feedback or if the interface is too black and white there may be no good way to master it and if a beginner and an advanced player have roughly the same chances of doing something there is no reason to try to become an advanced player.

Addiction of Exploration

The addiction of exploration has been in computer games since the beginning. In fact some of the first games were only about exploration. The game Adventure was a text game where the player could wander through areas looking around and collecting items, there were a few puzzles to be solved by getting items in combination to unlock more areas to explore. More recently the game of Myst also used this as its basis and has sold well over a million copies. The popularity of Myst cannot be ruled out as an anomaly as there is a strong urge in many people to explore interesting places and more than one game has capitalized on this. Games such as the Zork and Infocom text adventure series also were based on this premise and it is clear that this is a definite genre to be explored and not discounted.

Secret levels have also been the key of many games, from Super Mario Brothers to Final Fantasy 7, a main facet of the addiction was to find the secret levels. I once read that Shigeru Miyamoto (pride Nintendo’s design team who created Super Mario Brothers, Zelda, Metroid, et al) said that 40% of a video game’s levels should be hidden, it seems to have worked quite well for him.

Addiction of the High Score

The addiction of getting or beating a high score falls under two categories but is important enough to have a spot of its own. Normally someone who is trying to get a high score or some equivalent in a computer game is either trying to compete against other player’s scores or is trying to master the game. A huge amount of game playing has resulted simply from beating a high score of another. I believe this originated in Pinball games and still holds true in a more advanced way in the ladders of today’s Internet. If you haven’t already, take a look at them, they are extremely popular and have created their own sub-culture of sorts.

Another type of high score addiction is over winning a game. To do more than just finish the game. In the game of Super Mario Brothers, after you won you could continue to play with added difficulty. It became a measure of pride for some people to beat the game many times in one session or to perhaps beat the game once or twice without ever dying. For a while it was also very popular to see how fast you could beat the Legend of Zelda in one sitting. These types of addictions are variations of competing with others or with yourself and also fall into mastering the game.

Creating a way for your players to keep playing even after they have won the game, and giving them more incentive to play by making things harder and thus making it more challenging is another way you can add the element of addiction to your games.

篇目4,The Psychology of Immersion in Video Games

by Jamie Madigan

Along with “OMGDUDESOAWESOME” one of the words that gamers like to toss around when describing their favorite titles is “immersive.”1 But what exactly does that mean? And what makes a game immersive? Ask 5 people and you’ll probably get 10 opinions, but psychologists have been studying immersion in various kinds of media for decades so they could probably shed some light on those questions.

Except they don’t call it “immersion.” Instead, they call it “presence,” which, admittedly, isn’t as cool. Regardless, researchers have identified several kinds of presence in regards to how we perceive media but it’s spatial presence that I think comes closest to what gamers think of as “immersion.”

Briefly, spatial presence is often defined as existing when “media contents are perceived as ‘real’ in the sense that media users experience a sensation of being spatially located in the mediated environment.”2 The idea is just that a game (or any other media from books to movies) creates spatial presence when the user starts to feel like he is “there” in the world that the game creates. People who experience immersion tend to only consider choices that make sense in the context of the imaginary world. Someone immersed in Red Dead Redemption, for example, might be more likely to use travel methods that make sense within the game, like stagecoaches, instead of methods that don’t, like fast traveling from a menu screen. People immersed in media also tend to enjoy it more.

A Theory of Spatial Presence (aka, Immersion)

But how does this happen? What about a game and what about the player makes her feel like she’s leaving the real world behind? Theories abound, but a few years ago Werner Wirth and a team of other researchers sat down to consolidate the research and come up with one unified theory.3 Here it is:

Figure 1: It’s just that simple…

Woah, woah, woah. Sorry. Let’s just back up and take a simplified look at the parts most relevant to us gamers.

Basically, Wirth et al.’s theory says that spatial presence happens in three steps:

Players form a representation in their minds of the space or world with which the game is presenting them.

Players begin to favor the media-based space (I.e., the game world) as their point of reference for where they “are” (or to put it in psychological gobblety-gook, their “primary ego reference frame”)

Profit!

So, basically, the process starts with players forming a mental model of the game’s make-believe space by looking at various cues (images, movement, sounds, and so forth) as well as assumptions about the world that they may bring to the table. Once that mental model of the game world is created, the player must decide, either consciously or unconsciously, whether she feels like she’s in that imagined world or in the real one. Of course, it’s worth noting that this isn’t necessary a conscious decision with the prefrontal cortex’s stamp of approval on it. It can be a subconscious, on the sly, slipped into sideways and entered and exited constantly.

Researchers have extensively studied how these two steps happen, but I think it’s more interesting for our purposes here to skip to the bit about what qualities of the media (i.e., game) and person (i.e., player) that they’ve found facilitate both of these steps and create immersion. So let’s do that.

Game Characteristics Leading to Spatial Presence

Characteristics of games that facilitate immersion can be grouped into two general categories: those that create a rich mental model of the game environment and those that create consistency between the things in that environment.

Let’s take the concept of richness, first. This isn’t an exhaustive list, but richness relates to:

Multiple channels of sensory information

Completeness of sensory information

Cognitively demanding environments

A strong and interesting narrative, plot, or story

Multiple channels of sensory information means simply that the more senses you assault and the more those senses work in tandem, the better. A bird flying overhead is good. Hearing it screech as it does so is better. 3D may also play a role here, and we can all agree that smell-o-vision will herald in a new era of spatial presence.4

Red Dead Redemption is immersive in part because so many things work in tandem and it doesn’t leave many gaps to be filled in by the player’s imagination.

Completeness of sensory information means that the fewer blanks about the mental model of the game world that the player has to fill in, the better. Abstractions and contrivances (there are no people in this town because of, uh, a plague! Yeah!) are the enemy of immersion. Assassin’s Creed 2 was immersive because its towns were filled with people who looked like they were doing …people stuff. Dealing in a familiar environment also allows the player to comfortably make assumptions about those blank spaces without being pulled out of the world to think about it. Knowing what the wild West is supposed to look like and having Red Dead Redemption conform to those stereotypes goes a long way towards creating spatial presence.

Cognitively demanding environments where players have to focus on what’s going on and getting by in the game will tie up mental resources. This is good for immersion, because if brain power is allocated to understanding or navigating the world, it’s not free to notice all its problems or shortcomings that would otherwise remind them that they’re playing a game.

Finally, a strong and interesting narrative, plot, or story will suck you in every time. In fact, it’s pretty much the only thing in a book’s toolbox for creating immersion, and it works in games too. Good stories attract attention to the game and make the world seem more believable. They also tie up those mental resources.

Turning to game traits related to consistency, we have:

Lack of incongruous visual cues in the game world

Consistent behavior from things in the game world

An unbroken presentation of the game world

Interactivity with items in the game world

Lack of incongruous visual cues in the game world is one of the more interesting precursors to spatial presence. If we were discussing the same concept in movies, I’d cite the example of seeing a boom mic drop into an otherwise believable scene. It’s anything that reminds you that “Yo, this is A VIDEO GAME.” Examples might include heads up displays, tutorial messages, damage numbers appearing over enemies’ heads, achievement notifications, friends list notifications, and the like. It’s also the reason why in-game advertising wrecks immersion so much –seeing twenty five instances of ads for the new Adam Sandlar movie while trying to rescue hostages kind of pulls you out of the experience.

Seriously, who would use one of these things to keep an audio diary?

Believable behavior from things in the game world means that characters, objects, and other creatures in the game world behave like you’d expect them to. It’s also worth noting that the cues need to make sense and be constant throughout the experience. This is one reason that I think Bioshocks’s audio logs kind of hurt the game’s otherwise substantial immersion: Who the heck records an audio diary, breaks it up into 20-second chunks, puts them on their own dedicated tape players, and then wedges those players into the various corners of a public place? It doesn’t make any sense.

An unbroken presentation of the game world means that the spatial cues about the imaginary world your game has created should not just up and vanish. Which is exactly what happens every time you get a loading screen, a tutorial, or a game menu. When that happens, the game world literally disappears for a few minutes, and we can’t feel immersed in something that isn’t there.

Interactivity with items in the game world could probably fit under the “richness” list above, but I include it with consistency because it’s another way of giving the player feedback on actions and a sense of consistency between various parts of the environment. Operating machines, talking to NPCs, and fiddling with physics makes it seem like the various pieces of the world fit together consistently.

Games like Oblivion and Fallout 3 are immersive because they let you interact with almost everything.

Player Characteristics Leading to Spatial Presence

Of course, players have some say in how immersed they get in a game. Some people just have more spatial ability and can build those mental models of game worlds more readily and make them more vibrant. And researchers have found that people have an “absorption trait” which means that they’re quicker to get fascinated by something and drawn into it –something I like to think of this as “the fanboy gene.”

Other times the player takes a more active role. Some players simply want to believe in the illusion, and will induce their own bias towards accepting the “I am there” hypothesis. In this state, they’ll require less confirmatory information to accept that hypothesis and less disconfirming information to reject it. This is also similar to the idea of “suspension of disbelief” where players wilfully ignore stuff that doesn’t make sense (like thunderous explosions in space or the fact that enemy soldiers can soak up a dozen of gunshots without going down) in order to just have a good time.

Other researchers have also pointed to a concept they call “involvement” which is a media user’s desire to act in the make-believe world, to draw parallels between it and his life, and to effect changes in it according to their own design. To me, this seems like an overly fancy way of saying “some people like to role-play” which leads directly to greater immersion.

So there you have it. Everybody can cite examples of things that yank them out of the game experience, and it turns out that psychologists have examined, classified, and isolated a lot of them. This isn’t to say, though, that ALL games should strive to BE immersive. I think games are kind of unique in all media in that this is so. A game can still be a good game without being immersive, and maybe some types of games are better if they AREN’T immersive. But that’s the great thing: game designers have a lot of paths that they can take to good art.