举例阐述如何制作令人难忘的电子游戏NPC

今天我想谈谈NPC的问题。

我玩过大量的业余RPG,它们几乎都呈现出只会说“欢迎来到这个小镇”这种话的NPC。懒惰的游戏开发者会将NPC视为风景——仿佛他们只是地图的一部分,而并非活生生的角色。奇怪的是人们知道这种NPC很无聊和僵硬,但却很少花时间对其润色。希望本文能够让你获得如何创造出色NPC的启发。

何为NPC?

最简单的定义就是:非玩家角色。

但这似乎并不适合现代游戏。当我们严格遵从“非玩家角色”这一定义时,许多中心角色(例如主要的反派)也可以标为NPC了。虽然从技术角度来看,这一点可能是真的,但这一词的现代用法却更为具体:典型的NPC是那些不参与故事主要事件,居住在游戏世界中的平民。不少人会认为主要故事角色也是NPC,但我对此不敢苟同。

我们不在本文讨论这类角色,我将讨论的是游戏中的日常人物,那些让你的世界呈现生命力的劳动阶级。

制作令人难忘的NPC

为什么要多此一举?玩家只是想真正跳到下一个地下城,不是吗?如果你的MPC很糟糕,当然他们会马上转到下一个地下城。但这里有个问题:只有你给他们一个理由,他们才会去关心NPC。

游戏中之所以要有一系列不同的NPC,其中的一个明显原因就是,这可以让游戏世界更有深度。人们都有个性,你在游戏世界中融入的个性越多,游戏世界就越棒。人们都有生命——他们都有工作。如果你的NPC看起来只是为了玩家而存在,那么你的游戏沉浸感就会大打折扣。如果玩家记得他偶遇的每个人(或多数人),这个世界就会显得更真实。我认为游戏中的每一个NPC都应该有自身特点。

由于多数RPG都有个“拯救世界”的情节:那么他们就是你所拯救之人。这些人是我们打败邪恶巫师和拯救星球的原因。如果你同这些人毫无瓜葛,如果你没有关心他们的理由,那么你的任务吸引力就会严重下降。我喜欢《时之笛》中谢幕表中的字幕:你成功拯救了这个世界,你一路上所遇到的人们都围在篝火般庆祝这一刻。你认识他们,你在同个关卡或另一个关卡中曾与之互动,你觉得他们也认识你。你觉得自己真正解救了他们。这种感觉很棒。

想法和例子

让我们看看任天堂游戏《塞尔达传说》系列中一些令人难忘并值得学习的NPC。

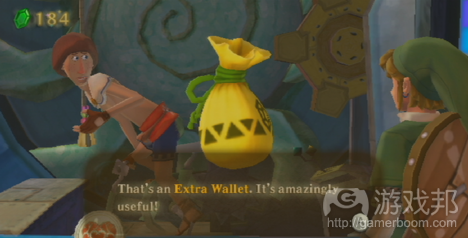

这是最早出现在《风之杖》,最近又现身于《天空之剑》中的Beedle。他的这两次出场,都是经营一家出售特殊道具的专卖店。他在这两次中都有极为独特的扮相和个性(以及声音——任何访问其小店的《风之杖》玩家都会记得Beedle那种拉长了的“谢……谢!”)。在《天空之剑》中,他呈现了更多深度。例如,你进入他的小店,但却空手离开时,他就会很生气并让你撞上活板门。除此之外,你还会发现他晚上在家的时候,已经没有那种独特的噪音,完全不同于“上班时间”的说话方式。

Beedle让我们看到:

小贩也可以富有个性。

为你的店主赋予独特的对话并非难事——让他们呈现特殊的爱好,为他们分配一些除了出售道具之外的事情。记住,经营小店并不仅仅是他们的日常工作,在小店背后应该是一个具有自身兴趣的人物。

现在让我们看看《时之笛》中的Ingo。他是接管Lon Lon农场并企图把你锁上(你得逃跑并救出自己的马Epona)的一个邋塌鬼,他的特点在于拥有完整的角色故事:在游戏刚开始时,他是一个懒惰的农场帮手,但七年后他同Ganondorf达成交易接管了农场(而前农场主Talon则待在了Kakariko的家中)。当玩家把Ingo打回原来的位置后,他就又变成了农场帮手,并因这一经历而变得谦卑。这是一个简单角色的简单故事,但已经足以赋予他个性,并增加游戏世界的深度。

Ingo证明:

NPC也可以随时间的发展而变化。

一个NPC就是一个角色,而我所着迷的一件事情就是角色发展。在你的游戏故事的发展过程中,要给予角色成长和变化的机会。如果你可以让他们根据玩家行动而发展,那更好!举个简单的例子,一个扮鬼脸的小孩在城中生闷气,因为他丢了一件道具,此时可以让玩家为他找回道具,那么这个小孩又会重展笑颜。记住NPC自己的生命也有故事,即使他们的故事并不是直接陈述出来,也可以通过对别人的暗示呈现出来。

Tingle! Tingle! Kooloo-Limpah! 许多人讨厌Tingle,但是我并不知道他在日本究竟有多大粉丝基础,我认为他是一个出色的NPC,因为他的辨识度相当高。Tingle是《梅祖拉的面具》中最令人难忘的角色之一。他坐在彩色气球上随处飘荡,当你突然出现时,他就会很急切地向你兜售世界地图。他不合时宜的亮色服装,疯狂的个性,以及对精灵的痴迷令其获得了极高的辨识度。但更重要的是,他有一个家——有位举办象形文字比赛的男人老是抱怨自己很失望,因为儿子已经这把年纪了却仍然对精灵所着迷。玩家不难猜出这位男人究竟是在说谁,因为当玩家亮出Tingle的画像时,这位男人就会为玩家提供创造联系的奖励。这个例子充分说明:

NPC彼此间也可以存在关系。

让我们再举一个不仅局限于交易的例子:NPC彼此间关系越亲密,游戏世界就会越有交互和真实感。让角色彼此认识,让他们拥有朋友和家人,同事。如果玩家可以同一位NPC交谈,并知道“这个男人对经营药品店的女子有意”,那么你就可以建立一种联系——这种关系并不仅局限于这两名NPC,玩家也在其中。它可以创造迷你游戏和支线任务,但即便只是在NPC对话中提及他人就足以为其增加令人难忘的深度。

Yeto和Yeta是《黄昏公主》中“最独特的地下城Snowpeak Ruins的中心人物。地下城就是他们的宅第,Yeto所煮的汤,你喝下就可以重新填充生命(游戏邦注:增加更多复杂性,地下城中没有复原之心,因为玩家能够通过这种方式复苏)但除此之外,他的妻子还可以告诉玩家地下城中不同珍宝的所在位置。在地下城末端,她却变身为丧心病狂的boss。这些角色说明:

NPC可以出现在地下城中。

地下城通常是黑暗而孤独的,但添加其他角色可以创造新的设计机会,并令整个地下城体验更有趣。要考虑到地下城是一个玩家追击敌人,或者需与好友并肩合作的地方。你的游戏越有交互性就越好。赋予NPC生命力就是一个好方法。

如果你玩过《梅祖拉的面具》,就会记得Kafei。他是游戏最大支线任务的主角,他的故事与Clock Town的大量居民相互交织在一起。对我来说,这款游戏中最令人难忘的部分并非地下城或boss,而是Kafei与爱人Anju重聚的任务。最后时刻,他们抓住对方在一片狼籍的背景中互诉衷肠的场面非常美妙。

《梅祖拉的面具》有一个独特的三日循环——在这三天中的不同节点,Kafei会出现在不同的区域。在某个节点,玩家必须在一个小偷的秘密巢穴中与Kafei见面。Kafei支线任务最令人难忘的部分在于,他在《塞尔达》系列中可玩角色的独特地位。Kafei会带你到处走动,他说明:

NPC可以移动。

在此我并不是指在村庄中小小的随机圈子中走动,而是让NPC具有移动性。如果你的NPC在外观和个性上具有辨识度,那么他就没有必要束缚于同一个地点。随着他故事的发展,可以让英雄在多个地点遇到他。记住,你的世界有居民,这些角色并不仅仅是场景。他们也要有动机,野心和目标。

他们有生命。

原文发表于2012年1月26日,所涉事件及数据以当时为准。(本文为游戏邦/gamerboom.com编译,拒绝任何不保留版权的转载,如需转载请联系:游戏邦)

Making Memorable NPCs

Yo. Today I feel like talking about NPCs.

I’ve played a lot of amateur RPGs and nearly all of them feature the same copy-paste “welcome to this town” NPCs. Lazy game developers will treat NPCs like scenery—like they’re just a part of the map and not living characters. The strange part is that people know that these kind of NPCs are boring and lame, but they rarely take the time to flesh them out. Hopefully this article can help you come up with some great NPC ideas.

What is an NPC?

The simplest definition is obvious: NPC stands for non-player character.

However, that doesn’t seem to cut it with modern games. When we strictly follow the “non-player character” definition, a lot of central characters—like major antagonists—should be labeled as NPCs. And while that might be true from a technical standpoint, the modern usage of the term is a bit more specific: typically NPCs are the commoners who inhabit the game world without being caught up in the major events of the story. Plenty of people would argue that major story characters are NPCs, too—and I can’t disagree with that.

For the sake of this article, we’re not talking about those characters. I’m talking about the day-to-day people, the working class citizens who make your world come to life.

Making NPCs Memorable

Why bother? The player just wants to skip ahead to the next dungeon, right? Well—if your NPCs suck, of course they will. Here’s a problem: the player will only care about the NPCs if you give him a reason to.

The obvious reason for a diverse cast of NPCs is that it gives the world depth. People have personalities, and the more personality you can cram into your game world the better it will be. People have lives—people have jobs. If your NPCs seem to exist only for the sake of the player, then your game’s immersion factor is slaughtered. If the player can remember every person (or most people) that he comes across, the world feels so much more real. I would argue that every single NPC in your game needs something unique about him or her.

Consider that most RPGs have a “save the world” plot: these are the people who you are saving. These people are the reason that we want to defeat the evil sorcerer and save the planet. If you have no connection to these people, if you have no reason to care about them, the magnitude of your quest will be significantly lessened. I love the sequence that plays during the end credits of Ocarina of Time: you’ve succeeded in saving the world and all of the people that you have encountered along the way are celebrating around a bonfire. You recognize them, you know them—you’ve interacted with all of them on some level or another—and you feel like they know you too. You feel like you’ve genuinely succeeded in helping them. It’s a good feeling—it’s a great feeling.

It was all worth it for them.

Ideas and Examples

Let’s look at some memorable NPCs from Nintendo’s The Legend of Zelda series and what we can learn from them.

This is Beedle, who first appeared in The Wind Waker and most recently in Skyward Sword. In both appearances, he runs a specialty shop that sells unique items. Also in both appearances, he has a very distinctive appearance and personality (and voice—anybody whose visited his shop in Wind Waker will remember Beedle’s “thaankyouuu!”). In Skyward Sword, he’s given even more depth. For example, if you go into his shop but leave without buying anything, he’ll get mad and drop you out a trap door. On top of that, you can find him at home at night, where he seems to lose his distinctive accent and speaks completely differently when he’s “off the clock”.

Beedle shows us that:

Shopkeepers can have personalities.

It isn’t hard at all to give your shopkeepers unique dialogue—have them show interest in a particular hobby, or give them something else to do other than sell you items. Remember that running a shop is just their day job; behind that shop menu is a person with interests of their own.

You’ll recognize this fellow; it’s Ingo from Ocarina of Time. He’s the scabby dirtbag who took over Lon Lon Ranch and tried to lock you up—until you escaped and rescued your horse, Epona. What’s cool about Ingo is that he has a full character arc: in the beginning of the game he is a lazy ranch hand, but after seven years pass he makes a deal with Ganondorf and takes control of the ranch (while Talon, the previous owner, is now found in a house in Kakariko). After the player puts Ingo in his place, he returns to being a ranch hand, humbled by the experience. It’s a simple arc for a simple character, but it’s enough to give him personality that makes him memorable and adds depth to the inhabitants of the world.

Ingo is proof that:

NPCs can change over time.

An NPC is a character, and one thing that I always obsess about is character development. Over the course of your game’s story, give your characters the opportunity to grow and change. If you can have them develop based on the actions of the player, even better! Take something as simple as a mopey kid wandering around town sulking because he lost an item: the player might bring it to him and then after that he will be happy and playful. Remember that NPCs have things going on in their lives; even if their stories aren’t being told directly, they can be shown and hinted at.

Tingle! Tingle! Kooloo-Limpah! A lot of people hate Tingle, and though I don’t really understand the massive fanbase that he has acquired in Japan, I think he’s a fantastic NPC because he’s so recognizable. Lets ignore his gimmicky side games; Tingle was one of the most memorable NPCs from Majora’s Mask. He floated around on his bright balloon and when you popped it, he would be eager to sell you maps of overworld areas. He’s instantly recognizable for his uncomfortably bright clothing, insane personality and obsession with fairies. But more importantly, he has a family: the man who runs the pictograph contest will grumble about he is disappointed because his son is too old to be obsessed with fairies. It isn’t difficult for the player to know exactly who means, and when he is shown a picture of Tingle, the man will reward the player for making the connection. This is a perfect example that:

NPCs can have relationships with each other.

Take it further than the obvious trading sequence: the more the NPCs are familiar with each other, the more the world feels interconnected and realistic. Let the characters be aware of each other—let them have friends and enemies, family members, co-workers. If the player can talk to an NPC and then think “so this guy has a crush on the lady who runs the potion shop”, then you’ve established a connection—not just between those two NPCs, but with the player as well. It opens up tremendous opportunities for minigames and side-quests, but even just including references in the NPC’s dialogue is often enough to give them memorable depth.

Yeto and Yeta appeared as central figures in Twilight Princess‘s most unique dungeon, the Snowpeak Ruins. The inhabit the dungeon—it’s their mansion, and Yeto is cooking soup and lets you replenish your life by drinking some (adding more complexity, there are no recovery hearts in the dungeon because the player is able to recover in this way). But in addition to that, his wife attempts to help the player by telling him the locations of different treasures in the dungeon. And at the end of the dungeon, she is revealed to be possessed and transforms into the boss. These characters show that:

NPCs can exist within dungeons.

And I would like to see a lot more of it! Dungeons are often dark and lonely, but adding some other characters can open up new design opportunities and make the entire dungeon experience a lot more interesting. Consider a dungeon where the player has to chase down an enemy, or has to work with a friend. The more interactivity in your game, the better. And giving life to NPCs is a great way to to that!

If you’ve played Majora’s Mask, then you remember Kafei. He’s the subject of the game’s largest side-quest, and his storyline intertwines with multiple residents of Clock Town. The most memorable part of the entire game for me isn’t the dungeons or the bosses, but the quest to reunite Kafei with his lover Anju. The final moments, where they clutch each other and proclaim their love against the backdrop of the apocalypse—is beautiful.

Majora’s Mask has a unique three-day cycle—and at different points within those three days, Kafei can be found in different areas. At one point, the player must meet Kafei at a thief’s secret lair. The most memorable part of the Kafei sidequest is that he holds the unique position in the Zelda series of being a playable character. Kafei takes you all over the place:

NPCs can move.

And I’m not talking about walking in little random circles in a village. Let the NPCs be mobile. If your NPC is recognizeable in appearance and personality, then he doesn’t need to be tied down to a single place. As his story progresses, let the hero encounter him in multiple areas. Remember that your world is populated, that these characters are not just scenery. They have motivations, they have ambitions, they have goals.

They have lives.(source:finalbossblues)

闽公网安备35020302001549号

闽公网安备35020302001549号