阐述时间因素对人们制定决策的影响

作者:Andrzej Marczewski

我现在对人们为何制定某些决策这一点很有兴趣。已经有大量文献在探讨这一话题,但真正吸引我的却是时间限制对制定决策的影响。

游戏中的时间限制

我们常在游戏中看到这种情况,有时候很明显,有时则不那么明显,其使用程度也不尽相同。

例如,《行尸走肉》就在特定对话中将其运用到了极致。系统会要求你制定一个决策,并给予你一些选择。在你决定的过程中,系统会进行倒计时,如果你不进行选择就会发生一种中立结果(可能还是你不希望看到的回应)。在游戏情境中,这会迫使你凭直觉而非长期考虑做出判断。这会给予你一种戏剧性之感,有时候还会有恐惧之感,通常情况下这些选择看起来都很消极——你只能选择最不坏的那一种。

在《马里奥》游戏的屏幕顶端也有一个计时器。多数时候它的意义不大,因为玩家总有足够的时间完成一个地图——但是,如果你决定搜集一个关卡中所有的道具时,通常就会发现时间远远不够用,总担心超过期限。

这些都是关于时间压力对决策影响的明显例子,因为你可以直接看到一个计时器,也明白在一定时间内会到期。但游戏还提供了其他类型的时间限制,例如你被击中时如何采取反应,在被敌人追杀时如何从地图一端奔向另一端等等。这些时间压力迫使你快速思考,执行反射动作,显然并不鼓励玩家进行思考或制定创意解决方案。但是,这种时刻通常给人以“真实”和情绪化之感,它们在那一刹那之间意义非凡。

有些人使用这一方法来获取工作情境中的“本能反应”。有个流行的“游戏”就是3-12-3及其变体。即设定一个问题,由一群人来设置解决这一问题的挑战。之后就有三个定时严格的头脑风暴阶段。第一个阶段持续3分钟,参与者需在这个时间想出主意。这种严格的时间限制导致参与者难以全面思考。接下来他们有12分钟开发一个比第一阶段的想法更为具体的理念。最后所有参与者需在3分钟内将自己的想法传递给其他人。此时规则会发生变化,个体、搭档和群体做的事情并不一致,但其关键原则却始终不变。最初想法的生成阶段限制时间较短。但这为何能够产生更妙的主意?

决策场理论——我们如何决定

我之前说过,人们已经做了许多关于我们如何制定决策的研究。我发现的最为杰出的一篇论文是由Jerome R.Busemeyer和James T.Townsend在1993年提出的决策场理论。在这个文献中,他们探讨了人们如何根据现成的信息和时间等因素制定决策。一般来说,你的大脑会通过所有现成信息过滤一系列选择。随着时间推移,每个选择的“胜算”机率也会发生变化,直到时间耗尽时你的脑中就会只剩下一个选择。我认为时间压力对制定决策的一个关键影响在于,改变制定决定所需的时间量,就可以极大改变结果。

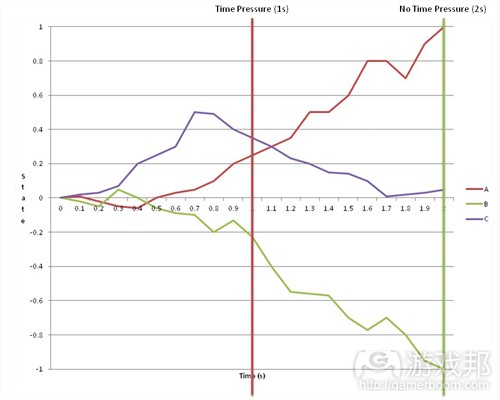

看看以下的图表。最后一条垂直线段(无时间压力)显示的是按照实际时间需求(2秒)所完成的决策。而A选择很显然是赢家。但是,如果将这一时间减半,你就会发现胜出的是C选择。

这当然并不代表A选择就比C选择更好或者更糟糕。其差别在于A选择考虑更为周全。实际上它可能是错误的,因为当C选择胜出时你所掌握的信息可能比A选择的信息更为准备。你可能会根据自己没有意识到的一些个人偏见而作出C选择。这些因素都会改变每个选择的有效性。再看我们之前的头脑风暴游戏,事实上更短暂的理念生成时间并不会产生更好的主意。它的作用在于给你机会想出晚多不含个人偏见的想法,而不是一定会更妙的主意。而在这之后的阶段,就会有时间考虑更多因素和创意。

解释水平理论——制定决策中的抽象vs具体感觉

所以时间是你制定决策时的一个影响因素。另一个制定决策时需要考虑的有趣因素的我们如何看待问题。在Yaacov Trope和Nir Liberman于1998年发布的“临时解释理论”(游戏邦注:它最后成为2010年心理距离解释水平理论的一部分)中,他们指出人们会因自己对某项事物的心理距离而对其产生不同看法。这可能是实体距离,暂时性的(时间)、社会因素等。他们与该物体距离越远,其解释或认知水平就越抽象/越高。与该物体越近,其解释水平就越具体/越低。这正是考虑为何需要做某事和如何做事之间的区别。

在《Not to be Miscoustrued》一文中,Nicolas Matthews举了一个很好的例子。你锁上一扇门,如果锁门的事件发生在未来,你可能是出于房子安全性而锁门。这正是你锁门的原因。当你拿着一把钥匙站在门前时,你此时此刻可能会想如何锁门。把钥匙插入门中,旋转钥匙,检查门。你离事件越近,该事件就越具体和现实。你就不会再去想为何要做此事,而是去想如何去做。

当你得到一个非限时任务时,你有足够的时间去考虑为何要做这种抽象问题。你可以排除选择,提出新想法,并迭代旧理念。你越接近制定决策的点,就越关注你如何完成给定的任务。

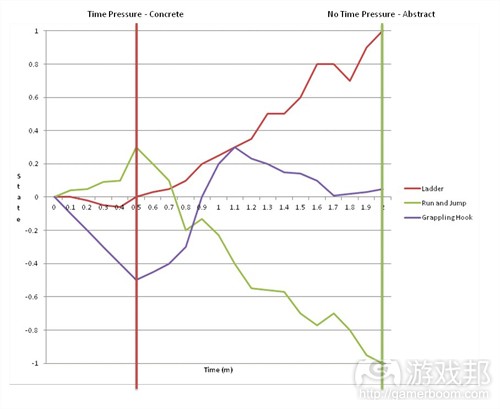

再举一例。你面前有一堵墙,你得翻过这堵墙。你有一条绳索,一个梯子和一个钩子。如果没有时间限制,你可以用多种方法实现目标。你可以飞攀檐走壁地越过墙体,可以创造一个抓升钩来翻墙。最后你还可以用梯子斜靠在墙上攀过去。面对这些选择,你可以根据自己的能力、喜好、墙体的高度等因素来选择,你可能会选择使用梯子。有些人可能会选择制作一个抓升钩,虽然这并不是最实用的方法,但却可能更有趣。因为你完成任务的时间并不紧迫,你可以想出抽象解决方法。

现在想象一下你被一群狗追到了墙角。你根本不可能用2分钟来作出选择,你得在30秒内翻过墙。突然间你没有时间进行抽象分析,跳过墙体似乎成了用时最短的上策。

而如果狗当时突然转向,跑到其他地方去了,对你来说其他方法可能才是更好的选项。

总结

时间是人们制定决策的一个重要因素,我们在设计任何系统时都不能忽视这一点。在游戏化系统中,我们有能力通过施加时间限制来实现我们的目标。

通过给予完成任务较短时间限制,我们可以限制人们所考虑的选择数量,但这却有可能让人们做出最现实的选择。将人们逼到紧要关头有利于他们做出更具体和现实的决策,给予他们更多直接意义。

给予较长考虑时间有助于人们策略更有深度的想法,提出更有创意的决定,但也可能导致人们由于个人偏见或其他外部因素而忽视很棒的想法。

要善于根据你所渴望的结果来利用时间因素实现你的目的。如果你想鼓励人们提出大量实用性的法,那就要缩减给予的时间。如果你鼓励人们发挥创意,提出更抽象的理念,那就给他们更多时间。(本文为游戏邦/gamerboom.com编译,拒绝任何不保留版权的转载,如需转载请联系:游戏邦)

The Effect of Time on Decision Making

by Andrzej Marczewski

The thoughts and opinions expressed are those of the writer and not Gamasutra or its parent company.

This was originally posted on my blog http://marczewski.me.uk/2013/08/05/the-effect-of-time-on-decision-making/

For a while now I have been fascinated with why people make certain decisions. There are loads of great papers out there, some of which I actually understand!

What has really caught my attention is the effect of time constraints on decision making.

Time Constraints in Games

We see this a lot in games, sometimes obvious other times, not so obvious. It is also used in varying degrees.

For example. In The Walking Dead, it is used to great effect during certain conversations. You will get asked to make a decision and are then given a few choices. Whilst you decide there is a progress meter counting down that will force neutral and probably unwanted response if you don’t choose. Within the context of the game, this forces you to often go with gut instinct over long considered decisions. This gives the feeling of drama and in some cases real dread, often the choices are all seemingly negative – you are left to choose which is least bad.

In Mario, there is always a timer ticking away at the top of the screen. For the most part this does not really mean much as it has ample time to complete a map – or so it seems. However, after deciding to collect everything on a level, you often find time running out and suddenly it all feels more desperate as you sprint to the finish line!

These are obvious examples of time pressure on decision making, you can see a timer and know it will run out at a certain point. Games offer many other types of time constraints, from how you react whilst being shot at to how you are going to get from one side of a map to the other as you are being chased. These kinds of pressures force fast thinking, reflex action and definitely don’t encourage considered or creative solutions. However, these kinds of moments often feel more “real” and emotional, they have more meaning in that split second.

Some people use this to get “gut reaction” decisions in the context of workshops and the like. A popular “game” is 3-12-3 or variations of it. A problem is set and groups of people are set the challenge of solving it. There are then three phases of the brainstorming process, all tightly timed. The first lasts 3 minutes and is used to come up with some ideas. Keeping the initial time tight forces participants to not over think the problem. Next they have 12 minutes to develop a more concrete idea from the ones pooled in the first phase. Finally the groups have 3 minutes to present their idea to the other groups. Rules differ, with individuals and pairs and groups doing various things, but the key principle is always the same. The initial idea generation phase has a short time limit. But why would this produce better ideas?

Decision Field Theory – How We Decide

As I say, there is a lot of research on how we make decisions. The most predominant that I found was a piece called Decision Field Theory published by Jerome R. Busemeyer and James T. Townsend in 1993. In this paper they discuss how people make decisions, based on available information and time etc. Basically, given a set of choices your mind filters through all of the information available. Over time the probability of each choice “winning” changes until either time runs out or there is only one choice left in mind. The key thing for me considering time pressure on decision making, is that changing the amount of time given for a decision to be made, can dramatically change the outcome.

Consider the graph below. The last vertical line (no time pressure) shows a decision that has been given its natural length of time to complete, in this case about 2 seconds. Here Choice A is the obvious winner. However, if the time is cut in half, you can see that at 1 second Choice C would win.

Decision Field Theory

This of course does not tell us if choice A was better or worse than Choice C. The difference is that Choice A is a more considered choice.In fact it may well be wrong, as the information you had when Choice C was winning may have been more accurate than the information you had at Choice A. You may have talked yourself out of Choice C based on some kind of personal bias you were not aware of. All sorts of things change the validity of each choice. Going back to our brainstorming game, in reality the shorter time given for idea generation probably doesn’t yield better ideas. What it does is give you a chance to generate more ideas without any of your natural bias’ kicking in, rather than ideas that are definitely better! After that you have time to be a little more considered and creative.

Construal Level Theory – Abstract vs Concrete Perception in Decision Making

So time is a factor in what decisions you make. Another interesting part of decision making to consider is how we perceive things. In 1998 Yaacov Trope and Nira Liberman published a paper called Temporal Construal Theory, which eventually became part of Construal Level Theory of Psychological Distance (CLT) (2010). This theory proposed that people thought about things differently based on the psychological distance between them and the thing. This could be physical distance, temporal (time), social etc. The further the experience is away from the object, the more abstract / high the level of construal or perception is. The closer the object is to the experience the more concrete / low level the construal is. This is the difference between considering WHY a thing needs to be done and HOW it is going to be done.

In his paper, Not to be Misconstrued, Nicolas Matthews gives a nice example of this. Consider locking a door. If the event of locking the door is in the future, you may think of it in terms of securing the house. This would be WHY you lock the door. When you are actually stood at the door with a key, you are more likely to think of HOW you lock the door as you are in the moment. Put key in door, turn key, check door. The closer to the event you are, the more concrete and real it becomes. You no longer have the luxury to think about why you need to do something; you have to think about how you will do it.

When given a task with unlimited (or at least ample) time, you have the luxury of considering the abstract thoughts of why. You can eliminate choices and come up with new ones and iterate old ones. The closer you are to the point the decision has to be made, the more focused you become on how you are going to achieve the given task.

A little example. You have a wall in front of you and are asked to go over it. To your side you have rope, a ladder and a hook. Given no time limit, there are a few ways you could do this. You could run and jump at the wall and try to climb over. You could create a grappling hook and use that to climb over. Finally you could just put the ladder against it and climb up that. Given those choices, and based on factors such as your own abilities, bias’, height of the wall etc, you may decide to use the ladder. Someone else may create a grappling hook, even though it is not the most practical, it may be more fun. As you are further away in time from the task, you can think of the abstract solutions.

Now imagine that you are being chased towards the wall by a pack of dogs. Rather than taking two minutes to make a choice, you have to make it before you get to the wall in 30 seconds. Suddenly you have no time for abstracts, this is the here and now. At this point, jumping the wall seems like the best and most practical solution for getting over it quickly.

time and decision making 2

If the dogs were to go in a different direction before you get to the wall, other ideas would begin to become better options for you.

Summary

Time is an important factor in decision making, one we can’t forget about when designing any kind of system. With gamification as in games, we have the ability to use it to our advantage by imposing time constraints on systems that would otherwise not have them.

By giving shorter time limits to achieve tasks, we limit the number of options that can be considered by people, but by doing so may promote the most practical options to rise to the top. Forcing people into the here and now will make those decisions feel more concrete and real, giving them more immediate meaning.

Giving longer time periods allows people to craft more thoughtful ideas and come to more creative decisions, but can also lead to people dismissing good ideas based on personal bias or other external factors.

Use time to your advantage based on the outcomes you desire. If you want to encourage lots of good practical ideas, reduce the time given. If you want to promote creative and more abstract thoughts, give them longer!(source:gamasutra)

闽公网安备35020302001549号

闽公网安备35020302001549号