关于叙述设计方法的4大层面

作者:Thomas Grip

本篇文章是关于处理游戏中的叙述设计的一种新方法—-主要有4个层面。这是以我在今年3月份所发表的GDC演说为基础。该方法主要是提出一个专注于故事并确保叙述和游戏玩法相连接的工作流程。而最终目标便是创造出能够提供更棒互动叙述的游戏。

叙述基础

首先,我们需要定义“叙述”。从最基本的层面来看,叙述是关于你在较长一段时间玩游戏时所发生的的事。它基本上就是全部的体验;即当所有的元素组合在一起所发生的事:游戏玩法,对话,注释,设置,图像等等;玩家穿越游戏的个人旅程。我知道这与其它关于叙述是区别于游戏的一种元素的定义相矛盾,但我认为这是在讨论游戏设计时最有帮助的定义。这同样也适用于“叙述设计师”的职称,即他们并不是指负责编写内容或过场动画,同时还致力于一些更高层面的工作。

让我们将其与其它游戏基本元素进行比较。以秒为基础着眼于一款游戏,你将会注意到核心机制。然后以分钟为基础继续着眼于它,你将会看到战术和问题的解决(同样也包含谜题等内容)。继续以小时为基础,你就会看到叙述。几乎所有的游戏设计都是专注于两个较低的层面,即机制和战术,而叙述经常是作为一种副产品。设计叙述变成了一种东拼西凑的过程,即你尝试着在较低层面的小缺口中创造连贯的故事感。举个例子来说,在基于战斗机制的游戏中,叙述经常是作为设置遭遇的一种形式,主要是如何斗争等等形式的约束。

所以在游戏中创造更棒的故事叙述的一大步骤便是像专注于其它两个层面(机制和战术)那样专注于叙述层面。我们不能将所有的精力都投入于故事中;确保两个层面间具有共生关系是创造一款特殊电子游戏的核心元素。如果我们想要看到适当的互动故事,我们便需要做到这点。

简单地来说便是,我们想要更多地专注于还很模糊的叙述层面;这并不是在告诉我们什么是有用的。所以我将通过列出互动故事所需要的5大基础进行更详细的说明。我们便是在此进入更加主观的领域,但这却是没有帮助的—-关于叙述和游戏玩法如何共事存在一个广泛的选择(游戏邦注:有些人甚至反对专注于叙述层面!)。但为了能够继续前进,我们需要拥有一些具体的内容;如果我们只是继续谈论“完善故事叙述”这样模糊的术语,那么任何建议都有可能击垮一些个人偏好的基础。这么做将只会让我们深陷于某些无聊的讨论中,并且很难设定一个适当的目标。

故事叙述的核心元素

以下的元素并不太具有争议性,我想大多数人都会认同它们。但我们仍需要承认这是一个选择,而不是我所认为的永恒真理。以下是我对于一款专注于叙述的游戏的核心要求。

1.重点是故事叙述。

这是一个琐碎的要求,但仍然很常见。从根本上看,游戏的主要目标应该是让玩家体验一个特别的故事。

2.大量的游戏时间花在游戏上。

我们想要的是互动故事叙述,所以玩家应该做的是游戏而不是阅读注释,观看过场动画等。虽然不能禁止这些内容,但它们不应该占据大部分体验。

3.互动让叙述变得有意义。

这意味着行动应该:

向前推动故事。

帮助玩家理解他们的角色。

与叙述相一致。

并不只是补充。

4.没有重复。

重复将导致我们注意到模式,而注意到游戏系统中的模式就会想去优化它们。一旦你开始基于“选择提供给我最棒的系统化结果”去思考游戏,你的注意力便会逐渐远离游戏的叙述元素。

5.没有主要的进程组块。

挑战并不存在本质问题,但如果这里的目标是讲述一个故事,那么玩家就不应该花好几天的时间徘徊于一个谜题中或尝试着克服一个基于技能的挑战。与重复一样,这将导致玩家的注意力偏离叙述内容。

一些突出的例子

现在让我们着眼于如下问题:什么样的游戏能够满足这些要求?

《骤雨》是否能够做到这些?不行,它缺少游戏玩法(不符合要求2)。

伴随着环境故事叙述的《生化奇兵》呢?不行,它带有太多射击内容(不符合要求4)。

这两款游戏都具有几乎所有电子游戏故事叙述所带有的基本问题:或者你不能玩够游戏,或者大多数游戏玩法与叙述并不相干。

还有一些有效的例子。《三十航班之恋》便是一款我认为符合这些要求的游戏。但是这里所具有的问题是其故事情节非常模糊且脱节。游戏是一系列模糊联系在一起的场景,缺少一定纯粹的故事叙述质量。

通过着眼于游戏的特定部分,我们进一步发现了一些符合要求的内容。其中两个例子便是《最后的生还者》中的长颈鹿场景以及《兄弟:双子传说》中的最终序列。这两个部分都有强烈的叙述感并符合我所说的要求。但这些都只是更大型游戏中的一些小场景,更大型的游戏甚至打破了我反复检查的核心元素。所以我们真正想要的是一款充满这些部分的游戏。这便是最完美的结果!

然而这是不可能的事。这些场景依赖于许多以前的游戏内容,并且很难去设置。你不能只是努力用这些内容去填充游戏,这是不可行的。为了获得一款能够不断唤醒这种感觉的游戏,我们必须从不同方向去处理它。

以下我将讨论如何做到这些。这是一个名为“4个层面”的方法,基本理念并不是直接攻击问题,而是将其分解成一些步骤,然后把适当的互动故事叙述整合到一些游戏部分中。

4个层面的方法

框架是由我和Adrian Chmielarz(游戏邦注:曾负责《Painkiller》和《Bulletstorm》等游戏)所开发的。在Frictional Games,我们将其作为新游戏《SOMA》的基础,而Adrian的新公司The Astronauts则将其用于他们即将问世的《The Vanishing of Ethan Carter》身上。

他们认为只有你将设计过程分成4个大步骤,这种方法才能发挥作用。你将从游戏玩法开始,然后添加更多故事叙述层面。额外的层面是叙述目标,叙述背景和最终的心理模式。

在获得更加深入的内容前,我们必须清楚为了有效地使用这一方法,游戏必须被划分成一些场景。每个场景都有一个谜题,一个敌人等内容。通常情况下游戏玩法是关于游戏整体如何运行,但对于这一框架,我们必须将其分割成一些部分。这与上述的没有重复内容的要求是相联系的,即意味着需要许多逻辑和游戏玩法整合到游戏世界中。我认为这是设置更棒的故事叙述的有效方法:丢下对于总体游戏循环的需求而不是创造匹配每个特定游戏场景的游戏玩法。

所以比起拥有描述玩家整体游戏体验的游戏玩法,叙述应该能够提供这样的结构。随着我们穿越不同的层面,这一切都会变得更加清楚。

层面1:游戏玩法

首先我们需要从基本的游戏玩法开始,并且必须从一开始就牢记叙述元素。如果游戏玩法并不匹配故事,那么问题就会不断累积,并导致你难以获得之后的层面并降低最终质量。所以作为确保这一点的第一步,你必须遵循4个基本规则:

1.一致性

游戏玩法必须匹配游戏世界,氛围和角色。在执行一个行动时并不需要进行反复思考;它必须匹配叙述所设定的一切。玩家应该能够思考用于更深入理解游戏故事的行动。玩家所做的同样也必须具有意义,不能直视作为随机或无意义互动的序列。来自《Gabriel Knight 3》的“胡子和猫”谜题便是关于不该做什么的显著例子。

2.流线型化

我们必须清楚游戏玩法不能太过复杂且不能有太多步骤。这将在某种程度上降低玩家受困的几率。当玩家受困较长时间时他们将专注于游戏玩法的机制或战术。同样地,我们希望让玩家能够预先计划并觉得自己了解游戏世界。如果任何时刻所需步骤都太过复杂,玩家便很容易失去沉浸感并失去对于目标的追求。这种情况经常出现在经典的冒险游戏中,即玩家需要完成许多步骤才能获得某些谜题的解决方法。

3.成就感

通常情况下这一元素都是被整合到核心游戏玩法中,但在专注于叙述的游戏中可能不是那么直接。当游戏的主要目标是讲述一个故事时,我们便很容易掉进“按压按键获得前进”的游戏玩法类型中。但为了让玩家觉得自己身处其中,你就必须带给他们成就感。用于唤醒这些成就感的挑战不需要是基于技能或谜题。以下是其它一些有帮助的内容:记忆任务,发散思维,刷任务,耐久性测试,困难的故事选择,序列休息,情节的理解,探索,导航,逃离迷宫,克服恐惧等等。

4.行动认证

当玩家在游戏中做某事时,他们必须理解自己在做些什么以及为什么要这么做。对于基本机制,这一切的出现都很自然,“我跳过洞口以避免掉落”,“我射击了那个人以免他会射击我”等等。但当提到不同场景时,情况并不总是这么直接。例如,玩家可能会无意中激活一些机器。如果这种情况太过频繁地出现,玩家便会开始优化他们的想法并不再推测自己的行动。这可能导致玩家觉得自己的体验是受到游戏的控制。

将所有的这4个规则整合到游戏玩法中并确保它们足够吸引人的确是个不小的壮举。大多数想要专注于故事叙述的游戏都止步于此。但是在4个层面的方法中,这还只是第1步。

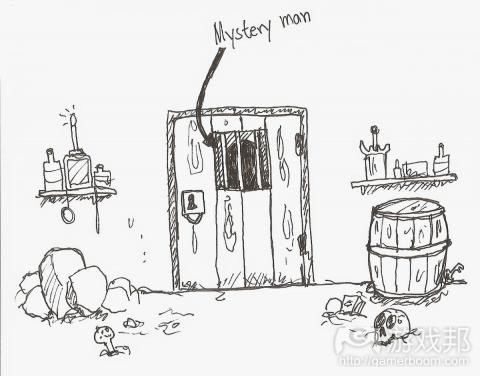

在移向下一个框架层面前,我将提供一个简单的游戏玩法例子。假设玩家被一扇上锁的门挡住了去路。一些早前的信息暗示玩家周围隐藏着开锁的钥匙,现在他们需要做的便是找到那把钥匙。这样的游戏玩法真的很简单且一点都不刺激,但却满足了上述所说的规则。

1.上锁的门与隐藏的钥匙不应该与故事发生冲突。

2.考虑到钥匙的搜索区域较小,玩家不可能受困。

3.要求玩家付出更多才能获得成就感。

4.设置合理,很显然玩家知道必须打开门,而钥匙是帮助他们做到这一点的道具。

之后我将使用其它层面进一步解释这一方法的使用。

层面2:叙述目标

所以下一步便是叙述目标。通常情况下玩家经历一些游戏环节的理由只是为了前进。存在一些支配一切的故事目标,如“杀死邪恶的巫师”,但这还是关于很远的将来,所以当玩家遭遇阻碍时,他们会尝试着克服它,因为这是游戏的要求。通常在这种情况下他们都处于“玩家模式”中,直到障碍被清除。这能帮助玩家知道自己该做什么,但对于叙述来说这却是个大问题—-它会破坏故事内部的体验。玩家将不知道他们的行动是作为故事中的一部分,反而认为它们是朝向抽象游戏目标的步骤。经常发生的是玩家会开始思考像“现在我需要离开这一部分从而能够继续在故事中前进”这样的内容,强制性的叙述和游戏玩法的分裂将彻底违背我们想要做到的融合。

解决这一问题的方法边上提供给玩家一些短期叙述目标,即与当前的游戏玩法具有直接的联系。这样做是为了确保玩家处于叙述模式中,如此他们便不会为了某些谜题或射击行动而把故事晾在一旁。当玩家沉浸于游戏玩法时,我们希望他们能够专注于叙述目标。这将让玩家很难去区分它们,因为他们总是能看到叙述目标。这不再是关于“因为故事而做模式”。区别也许看起来不大,但却的确具有差一些。我们必须记住这是基于一个基本层面,即碎玉一个只持续几分钟或更短时间的场景;玩家总是能看到叙述目标,并且总是会出现一些提醒内容告诉他们为什么要经历那些行动。

关于这一点的一个副作用便是因为目标的本质是叙述性,所以它将提供给完成游戏环节的玩家提供奖励。因为故事,玩家将产生动机去执行行动,然后将获得全新的故事章节作为奖励。总之,这将游戏玩法更加紧密地与故事叙述结合在一起。还有额外的副作用便是这能确保玩家处于正确的轨道上。玩家可能不确定下一步该做什么,但如果叙述目标与障碍的解决方法相联系,那么玩家便会因为对故事感兴趣而继续前进。

以下是能够使用的三种不同类型的叙述目标:

谜团

最显著且最简单的便是谜团;你想要找出一些未知的内容。我们很容易获得能够不断提醒玩家的环境资产—-这种目标总是很容易匹配游戏场景。

让人不安的环境

另一种方法便是提供给场景一个叙述原因让玩家不想在此逗留。最简单的例子便是一个黑暗且让人害怕的环境;玩家感到害怕并想要离开。也可以是让人尴尬的情景,玩家不想面对。例如,这可能是个压抑的场景,就像葬礼,会让玩家感到悲伤。重要的是不能陷入游戏机制中;这可能是让玩家不安的故事原因。我们想要专注于叙述而不是基础系统。

角色冲突

角色冲突也可以作为一个叙述目标。《行尸走肉》便充满这一元素;因为故事,那些真正简单的活动也变得吸引人了。一个有效的例子便是食物分配“谜题”,即玩家按照要求去决定如何分配剩下的食物。有趣的是玩家想不出一种至少不让其中一个角色失落的方法。任何可能导致玩家改变社会动态的游戏玩法都将作为强大的叙述目标。

这只是能做什么的3个例子,还有许多其它的例子、我认为你可以使用基本的写作技巧去想出更多。

现在让我们升级之前所提到的例子,即添加一个叙述目标。为了保持内容的简单,让我们列举一些谜团。假设门的另一端有个人尝试着要走进去。他想要检索玩家所处的房间内有什么东西,并让他们去开门。突然间存在关于想要开门的一个短期目标,这不再只是因为想要前进。“那个人是谁?”,“他所追求的目标是什么?”你想要找出这些问题的答案,这能够添加叙述动机。

注:4个层面的框架并不是个线性方法,你必须在不同层面间不断来回移动。在这种情况下,你需要检查第1个层面,游戏玩法,看看为了完善叙述目标是否需要更新哪些内容。你可能需要改变钥匙的隐藏位置,或者用其它内容换掉钥匙。

层面3:叙述背景

伴随着额外的叙述目标,如今的场景被框定在更具有故事性的模式中。但仍存在一个问题:玩家所执行的行动是专注于游戏玩法。在上述例子中,玩家搜索环境只是为了找到一个特定的道具;当玩家经历这些行动时并不存在适当的故事叙述感。这是因为这一层面是关于修改。

基本理念在于玩家应该做的行动是沉浸于故事内容中。所以当玩家进行互动时,这便不只是纯粹的游戏玩法,它们将同时变成联合故事。当添加了叙述目标时,玩家的思维将从“做某些事去推动故事的前进”变成“因为故事而要做某些事。”安置了叙述背景后,我们将其改变成“为了让故事出现而做某事”。基于叙述,玩家的行动将不再只是达到目的的手段,它们是玩家在游戏过程中导致故事出现的元素。通过确保行动和叙述节奏保持一致,我们让玩家很难区分这两者。这么做的目标是始终让玩家觉得自己身处故事中。

以下是关于这种类型的背景的一些例子:

故事片段

这意味着在环境中贯穿一些叙述线索,让玩家在游戏中能够偶然发现这些内容。在这里一个值得注意的要点不只是关于标准的音频日记记录。尽管这可能包含某些元素,但重要的是它们并非意味着游戏玩法中的大型中断,并且随着玩家不断克服游戏中的障碍,他们便会发现这些元素。收集线索的行为不应该让人觉得是单独的行为,而英国作为场景的主要游戏玩法的组成部分。

互补的对话

对话可以同时进行,即提供给玩家行动相关环境。《堡垒》便有效地利用了这一点。像敌人,升级道具以及易碎的板条箱等所有标准的游戏玩法元素都在游戏世界中拥有自己的一席之地。这也为类似的活动提供了一种多样感,即它们的叙述意义将具有多样性。《亲爱的爱思特》也是另外一个有效的例子。其中的步行行为对于游戏故事来说便非常重要。

具有重要情感的资产

如果游戏玩法中所包含的道具具有某种情感价值或与故事的强大联系,那么玩家便不会将它们作为抽象工具。在“选取前进所需道具”中,玩家会发现一些本身作为故事启示的内容。寻找“标准的刀A”与“杀人武器”具有巨大的区别。

这三个例子并不是你创造叙述背景的唯一方法。与之前的层面一样,这里也存在许多其它方法。

为了让内容更加具体,让我们回到示例场景中并添加一些叙述背景。首先,让我们以线索的形式添加故事片段。这些内容提供给玩家关于门背后的人的线索。图片,文件等的内容。当玩家在搜索钥匙的时候他们也将获得关于故事的线索。其次,让别人能够评论玩家的行动并提供给他们线索,让他能够透露自己的角色。再而,我们可以说这是那个藏起钥匙的人,而他这么做是出于一些重要的原因。基于这样的方法钥匙间具有叙述重要性,并且将不再只是一种抽象工具。添加所有的这些内容将要求我们改变谜题,但就像之前所说的,这并不是一种线形设计方法。你从之后的层面中学到的内容必须能够反馈到之前的层面中。

层面4:心智模式

现在我们来到了第4个层面,也是最后一个层面—-心智模式化。这一层面的目标是改变玩家感知并思考游戏的方式。我们想要挖掘玩家是如何评价自己的体验。

你必须清楚的一大重要事实便是当玩家在玩游戏时屏幕上的哪些内容不是最终出现在他们脑子里的内容。玩家也不是直接依赖于任何抽象系统去做出选择。玩家的大脑构建了游戏的心理模式,这是基于他们所看到,所听到以及所做的内容的虚拟反应。当你在选择接下来要做什么时便会使用这一模式。

这可能听起来有点诡异并且违反直觉的做法,但事实上它却不是如此。你只需要考虑玩家并未为了穿越一个空间而依赖于来自潜在系统的直接反馈便行。他们并不会为了明确自己可以去哪里而遇到每一堵墙。相反地,他们会使用现实世界中的知识,对于系统的直观判断以及视觉和听觉线索去决定该往哪条道路走去。一旦完成了计划,他们便会去执行计划。像这样的陈述听起来可能很琐碎,但如果你更认真地去思考它,便会发现这具有深刻的意义。

如果玩家做错某些事或当他们违背了自己的心智模式,他们便会清楚地感受到潜在的游戏系统。否则他们将在一款虚构的游戏中做计划。显然潜在的系统是确保它的运行,而系统和玩家输入间的反馈对于任何情况的发生都很重要。但系统却从未直接在玩家面前设下界限和选择。实际上,保持玩家的沉浸感总是与保持系统的隐秘性具有直接的联系。玩家并不是计算机也不能基于抽象数据表格做出决定。嵌入式大脑功能将能处理所有的这些内容,当玩家依赖于直觉时,游戏感便会发挥作用。不断探索一个系统去明确其真正构造从来都不是一种受欢迎的体验。(除非这是游戏的主题,即像有些益智游戏那样。)

边注:我需要强调的是当系统向玩家投入更多内容时,其直觉将出现升级。如果玩家一开始假设某些敌人能够跳跃但之后发现他们并不能这么做,那么他们的心智模式便发生了相应的升级。这将对叙述型游戏造成毁灭性的影响,让原本栩栩如生的角色变成不会说话的机器人之类。

在Brian Upton最初的《Rainbow Six》(1998年版的)中便拥有一个关于心智模式化的优秀例子。在《Rainbow Six》里,玩家将会因为被单发枪击中而死亡,并需要谨慎地前行。因为他们需要提防着对手,所以即使是一个非常简单的世界也具有许多游戏玩法,并且不需要玩家做太多事。举个例子来说吧,如果他们进入了一个新的房间,他们将停下来并尝试着想出最佳方法。他们需要考虑是否有人隐藏在那里等等问题。基于他们在游戏中的心智模式,他们将在脑子里模拟许多不同的方法,尝试着明确那种方法最有效。甚至是一条空荡的走廊也有可能召唤出这些思维过程。游戏充满了各种可能性,玩家需要去明确这些可能性,而唯一能够做到这点的方式便是使用对于游戏虚拟世界和居民的直觉。这种恒定的心智运转将是一种重要的体验。

这里的要点在于玩家脑子里的大多数想法都不具有系统性。玩家可能会想象一个守卫躲在角落里,并思考着它他如何环顾四周。因此,玩家的大多数游戏时间都是用于想象这样的内容。这看起来像是在逃避现实,并不像适当的游戏玩法,其实事实并非如此。这有点像象棋,即大多数游戏玩法是源自你对于情境的思考,真正的互动只能构成游戏时间中最小的部分。创造心智模式是一种非常有效的游戏形式。

在这里有很多游戏玩法并不能在游戏系统中转变成一个输入–输出循环。更重要的是,这种基于心智模式的游戏玩法是源自玩家关于游戏系统,图像和声音等等的更高层次的理解。这意味着这从根本上是与叙述维持着直接的联系。心智模式和叙述是位于同样的层次,它们是所有较低层次内容的集合。如果我们能够让它们运行在一起,我们便能够拥有最纯粹的游戏故事,即你便是在叙述空间里做出所有的游戏选择。这是值得我们去追求的目标。

同样有趣的是这种思维过程具有与书籍和电影同样的虚构属性。玩家的假设不需要100%正确,就像你不需要对小说所发生的场景具有最准确的猜想一样。如果玩家想象一个不存在的守卫躲在角落里,这也是可行的。他可能会慢慢地尝试着找出守卫的行踪,而未发现角落中躲着守卫也并不意味着幻想的破灭。现在玩家可以想象守卫悄悄地逃走了,或者其它类似的情况。当与系统进行直接的互动时,就像朝着明显的敌人发射子弹,玩家的假设也不能偏离现实太多。如果玩家想象被子弹打中但事实上却不是这样,那么他们的幻想便会迅速破灭。

注:假设你还未注意到,这一层面并不只是局限于单一的场景。它重复出现在游戏的许多环节中。当你拥有只持续较短时间的心智模式时,如果它能够跨越更多游戏环节,它便更加有效。

许多叙述游戏已经拥有某种程度的心智模式,但却是基于最糟糕的方式:收集品。假设你拥有一个关于恐怖森林的故事,主角尝试着明确什么是真正的内容。然后心智模式不断说着:“找到所有的热水瓶,你便会知道周围有什么。”这显然会使游戏失去许多潜能。你必须谨慎处理这样的问题。

相反地,你希望心智模式能够匹配剩下的叙述内容。以下便是对此的一些建议:

危险

存在一些潜伏因素是关于针对玩家的威胁构成。重要的是这些威胁并不是那些经常出现的行为。相反地,它必须是某些隐藏的内容,只能短暂地出现。这里所存在的理念是确保玩家能够在近处找到关于危险的线索。

基于目标的谜团

这意味着玩家带有解决罪行或其它之类的问题的目标。我们所追求的是玩家应该讲游戏世界当成是能够发现的重要线索。当玩家找到一个全新位置时,他们可以不断开始思考新内容会教会自己关于谜团的什么事。

社交压力

玩家是处在他们需要尝试着去识别的其他人之间。现在不管玩家何时找到一些新内容或看到NPC与之互动,他们都会升级有关动机的心智模式。

上述内容能够提供关于什么是可能的理念,但与之前一样,仍存在许多值得我们去探索的内容。

现在,我们是时候回到示例场景中并将第4个和最后的层面带进去。让我们添加一些危险。假设玩家在游戏中被多变的恶魔所捕获,这同样也是故事中的一大组成部分。这意味着玩家不能确定门后的人是朋友还是敌人。我们可以将这点与第3层面的内容整合在一起;当玩家发现了叙述背景,他们便会获得关于门后之刃的真正属性的暗示。

现在的我们已经从拥有一个关于打开门的简单谜题转向一个完整的故事。如今玩家所面对的威胁是另一面可能会出现某种恶魔,所以他需要努力寻找出关于这个神秘人的真实身份的线索。同时,这个人也是揭开谜团的关键。玩家一直在寻找钥匙,挖掘更多信息,并最终需要去决定自己是否要使用它。基本的游戏玩法并未发生太大的改变,但我们已经改变了外观,并彻底扭转了游戏体验。

尾注

关于这一方法我认为最有趣的是它会一直推动着你去思考故事。通常情况下我们很容易满足于需要深思熟虑的游戏玩法部分并暂时停止讨论。但是当你遵循了4个层面后,你就需要确保某些故事对于玩家正在做的事具有意义。故事将成为游戏设计中必不可少的组成部份。

这也可以作为过滤器。你可以评估每个游戏玩法场景并确保它的每个层面都符合标准。基于这一方法你可以轻松地判断某些部分是否只是过滤器,或者在某种程度上缺少着一座用。这是将设计维持在正轨上的一种有效的方法,并确保将注意力放在叙述上。

如果不具有任何问题的话这一方法也就不存在。

首先这要求许多计划。你需要事先进行设计,仅仅通过实验和迭代去创造一个场景是不现实的。设计文件非常重要,我们需要记录许多元素。

其次便是其核心力量同样也是最大的劣势。游戏玩法和叙述是相互交错的,如果你改变了其中一个,那么另外一个也需要进行更新。这意味着你需要在开发期间丢弃并重新塑造更多内容。但我并不认为这是一种失败,我将其当成是证实方法正在将游戏玩法和叙述更紧密地结合在一起的证据。

在某种程度上这一方法并不能真正改变游戏的核心元素。它只会添加一些小计谋。而这也正是我喜欢这种方法的理由。它并未依赖于任何我们并未拥有的内容。并且与所有优秀的故事叙述一样,它是依赖于用户对于做各种事情的想象。我真的很高兴看到这种方法能够成就最终的游戏。到目前为止这对于我们来说都是一种有效的方法,我也希望你们能够受到鼓舞而尝试看看。

(本文为游戏邦/gamerboom.com编译,拒绝任何不保留版权的转载,如需转载请联系:游戏邦)

4-Layers, A Narrative Design Approach

By Thomas Grip

This article will be about a new way to approach narrative design in games – the 4 Layers Approach. It is based on a GDC talk I gave in March this year. The approach is primarily meant to suggest a workflow that focuses on the story and makes sure the narrative and gameplay are connected. The end goal is to create games that provide a better interactive narrative.

Narrative Basics

First off, “narrative” will need to be defined. At its most fundamental level, the narrative is what happens as you play the game over a longer period. It is basically the totality of the experience; something that happens when all elements are taken together: gameplay, dialog, notes, setting, graphics etc.; the player’s subjective journey through the game. I know this clashes with other definitions that refer to narrative as a separate aspect of the game, but I think this is the one that’s most helpful when discussing game design. It also fits with job titles such as “narrative designer”, who is a person that doesn’t just deal with writing or cut-scenes, but who works at a much higher level.

Quick note: A deep dive into various story-related terminology can be found here.

Let’s compare this to the other basic elements of a game. Looking at a game second-by-second, you see the core mechanics. Moving up to look at it using a time-frame of minutes, you see tactics and problem-solving (which also includes things like puzzles). Higher still, often on the scale of hours, you see the narrative. Almost all game design is focused on the two lower levels, mechanics and tactics, and narrative mostly comes out as a sort of byproduct. Designing the narrative becomes a sort of patchwork process, where you try and create a coherent sense of storytelling from the small gaps left behind by the layers below. For instance, in games based on combat mechanics the narrative usually just acts as a form of set-up for encounters and is heavily constrained by how the fights work and so forth.

So a crucial step towards better storytelling in games is to give at least as much focus to the narrative layer as to the other two layers, mechanics and tactics. It is important to not devote all the focus to the story though; having a symbiosis between all of layers is a core element of what makes video games special. If we want proper interactive story, we need to preserve this.

Simply saying that we want to put more focus on the narrative level is still pretty vague; it doesn’t tell us anything useful. So I’ll make it a bit more concrete by listing five required cornerstones of an interactive story. This is where we get into highly subjective territory, but that can’t be helped – there’s a wide span of opinions on how narrative and gameplay should work together (some would even object to having focus on the narrative layer at all!). But in order to move on we need to have something concrete; if we just continue to talk in vague terms of “improving storytelling”, any suggestion can be shot down on the basis of some personal preference. Doing it like that will just get us stuck in boring discussions and it becomes much harder to set a proper goal.

Core Elements of Storytelling

The following elements shouldn’t prove too controversial and I think most people will agree with them. But it still feels important to acknowledge that this is an opinion and not something I regard as an eternal truth. That said, here are my core requirements for a game with focus on narrative.

1) The focus is on storytelling.

This is a trivial requirement, but still way too uncommon. Basically, the main goal of the game should be for the player to experience a specific story.

2) The bulk of the gameplay time is spent playing.

We want interactive storytelling, so players should play, not read notes, watch cutscenes, etc. These things are by no means forbidden, but they should not make up the bulk of the experience.

3) The interactions make narrative sense.

This means actions that:

Move the story forward.

Help the player understand their role.

Are coherent with the narrative.

Are not just there as padding.

4) There’s no repetition.

Repetition leads to us noticing patterns, and noticing patterns in a game system is not far away from wanting to optimize them. And once you start thinking of the game in terms of “choices that give me the best systemic outcome”, it takes a lot of focus away from the game’s narrative aspects.

5) There are no major progression blocks.

There is no inherent problem with challenge, but if the goal here is to tell a story, then the player should not spend days pondering a puzzle or trying to overcome a skill-based challenge. Just as with repetition this takes the focus away from the narrative.

There is a lot more that can be said about these requirements, all of which you can find here.

Good Examples To Strive For

Now for the crucial follow up question: what games satisfy these requirements?

Does Heavy Rain manage this? Nope, there’s too little gameplay (requirement #2).

Bioshock, with all the environmental storytelling? Nope, too much shooting (requirement #4).

These two games symbolize the basic issues almost all video game storytelling have: either you do not play enough, or most of what the gameplay does is not related to the narrative.

There are a few good examples, though. Thirty Flights of Loving is a game that I think lives up to the requirements. But the problem here is that the storyline is extremely fuzzy and disjointed. The game is a series of vaguely connected scenes, and is lacking a certain pure storytelling quality.

We come much closer to finding something that lives up to the requirements by looking at specific sections in games. Two good ones are the giraffe scene in The Last of Us and the end sequence in Brothers: A Tale of Two Sons. Both of these sections have this strong sense of being inside a narrative and fulfill my requirements. You are definitely playing a story here. But these are just small scenes in a much larger game, and that larger game breaks most of the core elements that I have gone over. So what we really want is to have a full game filled with these sorts of sections. That would be perfect!

However, that isn’t possible. These scenes depend on tons of previous game content and are extremely hard to set up. You cannot just simply strive to fill the game with stuff like this, it’s just not doable. In order to get a game that consistently evokes this feeling, we have to approach it from a different direction.

This leads us to the main bulk of this article, where I’ll talk about a way to achieve this. This is an approach named “4 Layers” and the basic idea is to not attack the problem directly, but reduce it into steps and thereby be able to get proper interactive storytelling into just about any section of the game.

The 4 Layers Approach

The framework is something that’s been developed between myself and Adrian Chmielarz, the man responsible for Painkiller, Bulletstorm, etc. At Frictional Games we are using this a cornerstone for our new game SOMA, and Adrian’s new company, The Astronauts, is using it for their upcoming The Vanishing of Ethan Carter.

They way this approach works is that you divide the design process into four big steps. You start with the gameplay and then work your way through adding more and more layers of storytelling. The additional layers are Narrative Goal, Narrative Background and finally Mental Modeling.

Before I get more in-depth it is important to note that in order to use this approach correctly, the game must be broken down into scenes. Each scene could be a puzzle, an enemy encounter, and so on. Normally, gameplay refers to how the game plays out as a whole, but for this framework, we must split it up into sections. This is connected with the above requirement of not having repetition, and usually means that there needs to be a lot of logic and gameplay coded into the world. I think that this is presents a crucial piece of the puzzle for having better storytelling: to drop the need for an overarching play loop and instead make the gameplay fit each specific scene of the game.

So instead of having the gameplay describe the player’s overall experience of the game, the narrative will provide this structure. Exactly how this is done will become more apparent as we go through the different layers.

Layer 1: Gameplay

First we need to start with the basic gameplay and it’s crucial that the narrative aspects are kept in mind from the get-go. If the gameplay doesn’t fit with the story, then problems will start to accrue and it’ll make the later layers much harder to achieve and reduce the final quality. As a first step for ensuring this, there are four basic rules that must be followed:

1) Coherency

The gameplay must fit with the game’s world, mood and characters. There should be no need for double-thinking when performing an action; it should fit with what has been laid out by the narrative. The player should be able to think about the actions made to get a deeper understanding of the game’s story. What the player does must also make some sort of sense and not just be a sequence of random or nonsensical interactions. The infamous “mustache and cat”-puzzle from Gabriel Knight 3 is a shining example of what not to do.

2) Streamlining

It is important that the gameplay is not too convoluted and doesn’t have too many steps. This is partly to minimize the chance of the player getting stuck. When the player is stuck for longer periods they focus on the mechanics or tactics for gameplay. Also, we want to have situations where the player can plan ahead and feel like they understand the world. If the steps required for any moment are too complicated, it’s very easy to lose immersion and to lose track of the goal. This happens very often in classic adventure games, where the solution to something straightforward requires a massive number of steps to accomplish.

3) A Sense of Accomplishment

This sort of thing is normally built into the core gameplay, but might not be as straightforward in a narrative-focused game. It is really easy to fall in the trap of doing “press button to progress” type of gameplay when the main goal is to tell a story. But in order to make the player feel agency, there must be some sense of achievement. The challenge needed to evoke this sense of accomplishment does not have to be skill or puzzle-based, though. Here are a few other things that could be used instead: memory tasks, out-of-the-box thinking, grind, endurance tests, difficult story choices, sequence breaks, understanding of the plot, exploration, navigation, maze escape, overcoming fear and probably tons more.

4) Action Confirmation

When the player does something in the game, they must understand what it is that they are doing and why they are doing it. For basic mechanics this comes naturally, “I jumped over the hole to avoid falling down”, “I shot the guy so he would not shoot me back” and so forth. But when taken to the level of a scene it is not always as straightforward. For instance, the player might accidentally activate some machinery without being aware that this was going to happen beforehand and afterwards not knowing what it accomplished. If this occurs too frequently, the player starts optimizing their thinking and stops reasoning about their actions. This then leads to an experience where the player feels as if they are just pulled along.

Getting all of these four rules into a gameplay scene and also making sure it is engaging is no small feat. Most games that want to focus on storytelling stop here. But in the 4-Layer approach this is just the first step.

Before moving on to the next layer of the framework, I will give a simple gameplay example. Say the player encounters a locked door blocking their path. Some earlier information has hinted that there is a key is hidden nearby, and now they need to search the room to find it. Once they find the key they can unlock the door and progress. Very simple, and not very exciting, but it fulfills rules set up above.

1.A locked door and hidden key should not conflict with the story.

2.Given that the search space for the key is rather small, it is not likely the player will get stuck.

3.It requires enough from the player to give a sense of accomplishment.

4.Set up correctly, it should be very obvious to the player that the door needs to be opened and the key is the item used to accomplish this.

I will come back later and expand upon this with the other layers to give you a better feel for how the approach works.

Layer 2: Narrative Goal

So, next step: the narrative goal. Normally the reason for the player to get through some gameplay segment is just pure progress. There is often some overarching story goal like “kill the evil wizard”, but that is quite far into the future, so when the player encounters an obstacle they try to overcome it because that is what the game demands of them. It is often very clear that they are in “gamer mode” at this point and until the obstacle is cleared. This is useful in order for the player to know what to do, but it is very problematic for the narrative – it removes the experience of being inside a story. The player stops seeing their actions as part of a story and instead sees them as steps towards an abstract gameplay goal. What can often happen is that the player starts thinking stuff like “Now I just need to get this section out of the way so I can get on with the story”, a forced mental division between narrative and gameplay, which is diametrically opposed to the fusion we’re striving for.

The way to fix this is to give the player some sort of short-term narrative goal, one that is directly connected to the current gameplay. The aim is to keep the player in narrative mode so they do not brush the story aside for some puzzling or shooting action. When the player is engaged in the gameplay at hand we want them focused on and motivated by this narrative goal. This makes it harder for the player to separate the two, as the narrative goal is always in sight. It is no longer about “doing stuff to get the story going”, instead it is about “doing stuff because of the story”. The distinction might not seem that big, but it makes all the difference. Keep in mind this is at a local level, for a scene that might just last a few minutes or less; the narrative goal is constantly visible to the player and a steady reminder of why they are going through with the actions.

A nice side-effect of this is that since the goal is narrative in nature, it becomes a reward for completing the gameplay section. The player is motivated to go through actions because of story and is then promptly rewarded with a fresh piece of the story. In all, this binds the gameplay much more tightly to the storytelling. An additional side-effect is that it can keep the player on the right track. The player might not be sure what to do next, but if the narrative goal is connected with the solution to the obstacle, then the player will progress simply by being interested in the story.

Here are three different types of narrative goals that could be used:

Mystery

The most obvious and simple is mystery; that there is something unknown you want find out about. It’s pretty easy to have environmental assets that constantly reminds the player of this – this sort of goal is also pretty easy to fit into a gameplay scene.

Uncomfortable Environment

Another way is to give the scene a narrative reason for the player not wanting to stick around. The most trivial example of this would be a dark and scary environment; the player is scared and wants to leave. It could also be that the situation is awkward or emotional in a way that the player can’t cope with and wants to escape. For example, it could be a depressing scene, like a funeral reception, that makes the player sad. It’s important, though, not to get caught up in game mechanics; it must be a story reason that makes the player uncomfortable, not some mechanic (spikes popping up here and there, etc.). We want the focus to be on the narrative, not the underlying systems.

Character Conflict

Character-based conflict can also be used as a narrative goal. Walking Dead is full of this; what are really just fairly simplistic activities become engaging because of story reasons. A great example is the food distribution “puzzle” where the player is instructed to determine how the remaining stash of food is divided. What makes it interesting is that the player cannot come up with a division that doesn’t upset at least one of the characters. Any gameplay that results in the player changing the social dynamics can act as powerful narrative goal.

These are just three examples of what could be done and there are bound to be a ton more. I think you could use basic writing techniques to come up with more.

Now let’s update the example from before and add a narrative goal. To keep it simple let’s go with some mystery. Say there’s a man on the other side of the door trying to get in. He wants to retrieve something that’s in the room that the player is currently in, and is asking them to open the door. Now all of a sudden there’s a short-term goal for wanting the door open, and it’s no longer just due to wanting to progress. “Who is this man?”, “What object is it that he’s after?” You want to get these questions answered and that adds narrative motivation.

Note: The 4-Layers framework is not a linear method, you’ll have to constantly skip back and forth between the layers. In this case, you need to check the first layer, gameplay, and see if there’s anything that could be updated in order to improve the narrative goal. You might need to change where the key is hidden, or even exchange the key for something else.

Layer 3: Narrative Background

With the addition of a narrative goal, the scene is now framed in a much more story-like manner. But there is still an issue: the actions the player does are quite gameplay-focused. In the above example, the player searches the environment simply in order to find a certain item; there is no proper sense of story-telling going on as the player goes through these actions. That is what this layer is all about fixing.

The basic idea is that the actions the player is supposed to be doing are immersed in story substance. So when the player is interacting, it is not just pure gameplay, they are constantly being fed story at the same time. When the narrative goal was added, the player’s thinking was changed from “doing stuff to get the story going” to “doing stuff because of the story”. With narrative background in place we change it to “doing stuff in order to make the story appear”. Narrative-wise, the player’s actions are no longer just a means to an end, they are what causes the story to emerge as you play. Or at least that’s how we want it to appear to the player. By having the gameplay actions and the narrative beats coincide, we make it hard for the player to distinguish between the two. The goal is for this to lead to a sense of always being inside a story.

Here are a few examples of the kind of background that can be used:

Story Fragments

This means having narrative clues scattered through the environment which are stumbled upon while playing. An important note is that shouldn’t just be the standard audio logs and diary entries. While it can consist of those sort of elements, it’s important that they never mean a large interruption in the gameplay, and that they’re found as the player goes through with the actions needed to overcome the obstacle. The act of collecting clues should not feel like a separate activity, but come as a part of the scene’s main gameplay.

Complementary Dialog

There can also be dialog going on at the same time, giving context to the player’s actions. Bastion uses this to great effect. All of the standard gameplay elements like enemies, power-ups and breakable crates are given a place in the world and a sense of importance. It also gives a great sense of variation to similar activities, as their narrative significance can be quite diverse. Dear Esther is another good example of this at work. Here the simple act of walking is given the sense of being vital to the story.

Emotionally Significant Assets

If the the items involved in the gameplay have some sort of emotional value or a strong connection to the story, the player is much less likely to see them as abstract tools. Inside of picking up “item needed to progress”, the player finds something that can be a story revelation in itself. There is a huge difference in finding “standard knife A” and “the murder weapon from a hideous crime”.

These three are of course not the only methods at your disposal to create narrative background. Just like with the previous layer, there are bound to be tons of other things too.

To make things a bit more concrete, let’s go back to the example scene and add some narrative background. First off, let’s add story fragments in the form of clues. These can give hints to the player about who the man behind the door is. Pictures, painting, documents and so on. So while the player is searching for the key they’ll also be fed hints about the story. Secondly, let’s have the man comment on the player’s actions and give hints, making him reveal his character a bit. Third, we could say that it was the man who hid the key and that he did so for some very important reason. That way the key has some narrative significance and is not just an abstract tool. Getting all of these things in might require us to change the puzzle a bit, but as said before, this not a linear design approach. What you learn from the later layers must be fed back into the previous ones.

Layer 4: Mental Modeling

Now comes the 4th, and final, layer – Mental Modeling. The goal with this layer is to change the way the player perceives and thinks about the game. We want to tap into how the player evaluates their experience.

The first and crucial fact you must be aware of is that what is actually on the screen when the player is playing is not what ends up in their head. Nor does the player rely directly on any abstract system to make choices. The player’s brain builds up a mental model of the game, a sort of virtual representation based upon what they see, hear and do. It’s this model that’s used when you choose what to do next.

This might seem a bit bizarre and counter intuitive but it really isn’t. Just consider how a player doesn’t rely on direct feedback from the underlying systems in order to traverse a space. They don’t bump into every wall in order to check where they can go. Instead they use their knowledge of the real world, intuition of the systems, and visual and auditory clues to plan a path. And once that plan is finished (which for simple tasks like walking takes a fraction of a second), the plan is executed. Stated like this it sounds really trivial, but if you think about it a bit more, it’s actually quite profound.

The underlying gameplay systems only really become evident for the player if they do something wrong or when they directly contradict their mental model. Otherwise they play and plan largely in part based on an imaginary game. Obviously the underlying system is what keeps it all working, and the feedback between the systems and the player’s input is crucial for anything to happen. But the systems are never directly queried to lay out the boundaries and options available to the player. In fact, keeping the player’s sense of immersion is often directly related to keeping the systems hidden. The player is not a computer and doesn’t make decisions based on tables of abstract data. Built-in brain functions handle all that, and the smoothest sense of play comes about when the player is relying on gut feeling and intuition. Constantly having to probe a system to figure out its exact make-up is almost never a pleasing experience. (Unless that is what the game is all about, as is the case with some puzzle games).

Side note: I need to note that the player’s intuition is updated the more that a system is revealed to them. If the player first assumes some enemies can jump but later finds out that they can’t, their mental model is updated accordingly. This can have devastating effect on a narrative-focused game, making life-like characters turn into dumb automatons and so on. For more information on how all that works, check this out.

Brian Upton has a great example of mental modeling in action based on his work with the original 1998 Rainbow Six. In Rainbow Six the player dies from a single shot and has to be very careful how they progress. Since they are constantly on the look out for hostiles, even a very simplistic world can have a lot of gameplay, and that’s without the player doing much. For instance, if they are about to enter a new room they stop and try to figure out the best approach. They need to consider if someone might be hiding out of sight and so forth. Based on their mental model of the game they will simulate many different approaches in their mind, trying to figure out which will work best. Even an empty hallway can conjure up these sorts of thought processes. The game is filled with possibilities that the player needs to be aware of, and the only way to do this is to use their intuition on how the game’s virtual world and its inhabitants work. These constant mental gymnastics are a crucial piece of the experience.

The important point here is that most of what exists in the player’s mind has no systemic counterpart. The player might imagine a guard hiding behind a corner, thinking of how he might be looking around. But in reality there is no guard behind the corner. Thus, a great deal of the playing time is spent just imagining stuff. This might seem like a cop-out, and not like proper gameplay, but that’s not the case at all. It’s sort of like chess, where most of the gameplay comes from you thinking about a situation, and the actual interaction only makes up minor portion of the playing time. Making mental models is very much a valid form of play.

The takeaway here is that there is a lot of gameplay which doesn’t translate into an input-output loop within the game’s systems. And more importantly, this sort of mental model-based gameplay comes from the player’s high level interpretation of the game’s systems, graphics, sound and so forth. This means that it basically ties directly into narrative. The mental model and the narrative lie on the same level, they are the accumulation of all the lower level stuff. And if we can get them to work together, then what we have is the purest form of playable story where all your gameplay choices are made inside the narrative space. This is clearly something worth striving for.

What’s also interesting is that these sort of thought processes share the imaginary nature of books and film. The player doesn’t have to be 100% correct with all assumptions, just like you don’t have to have a perfect mental recreation of the locale a novel takes place in. If the player imagines a non-existent guard being around the corner then that is OK. He might approach slowly trying to get signs of the guard’s whereabouts and not finding a guard behind the corner doesn’t need to mean the fantasy is broken. The player can now imagine that the guard soundlessly snuck away, or something similar. When interacting directly with systems, like shooting bullets at a clearly visible enemy, the player’s assumptions can’t stray very far from reality. If the player imagines the bullets hitting when they in fact don’t, that fantasy will quickly be broken.

Quick note: In case you haven’t already noticed, this layer isn’t just confined to a single scene. It’s something that overlaps a lot of of the game. While you could potentially have mental models that only last for short durations, it is more effective when it spans a greater part of the game.

Many narrative games already have some degree of mental modeling, but in the worst way possible: collectables. Say you have this story about a creepy forest and a protagonist trying to figure out what is real. And then picture the mental model constantly saying: “find all the thermoses, you know there are some around”. This will obviously make the game lose a lot of its potential. Be wary of this kind of issue.

Instead you want to have a mental model that fits with the rest of the narrative. What follows are a few suggestions:

Danger

There is something lurking about that constitutes a threat for the player. It’s important that this threat is not some common occurrence that relies on twitch reflexes or similar, as it’s just a normal gameplay element then. Instead it must be something hiding, only making brief appearances. The idea is for the player to constantly scan the environment for clues that the danger is near and present.

Goal-focused Mystery

This can mean that the player has the objective of solving a crime or similar. What we are after is that the player should see the game world as a place where important clues are to be discovered. So whenever the player finds a new location they should instantly start thinking about what new things it can teach them about the mystery.

Social Pressures

The player is amongst other people that they have to try and figure out. Now whenever the player finds something new or watches NPCs interact it updates their mental model of what makes the characters tick and what their motivations are.

The above should give an idea of what is possible, but as before, there are probably tons more to explore.

Now it’s time to go back to the example scene and update it with the 4th and final layer. Let’s add some sort of danger. Say the player is hunted by shape-shifting demons throughout the game and that these are also a big part of the story. This means the player won’t be sure if the man behind the door is a friend or foe. We can tie this into the layer 3 stuff as well; as the player uncovers the narrative background they receive hints about the true nature of the man behind the door as well.

We’ve now gone from just having a really simplistic puzzle about opening a door to an entire story experience. The player is now under threat that there might be some kind of demon on the other side and is desperately trying to find clues on what the secret man’s true identity is. At the same time, the man is also the key to a mystery, a mystery the player is very curious to figure out. The player is scavenging for the key, digging up more information as he goes along and when he finally finds it he needs to decide whether to use it or not. The basic gameplay hasn’t changed much, but we’ve changed the wrapping and it totally transforms the experience.

Endnotes

What I think is extremely interesting about this approach is that it always forces you to think about story. Normally it’s so easy to just be satisfied with a well-thought-out gameplay segment and to leave it at that. But when you follow 4-Layers you need to make sure that there’s some story significance to the activity the player is currently doing. Story becomes an essential part of the game design.

It can also act as a filter. You can evaluate every gameplay scene and make sure it fulfills the criteria in each of the layers. This way you can easily tell if a some segment is just filler, or lacks in some other way. This is a great way to keep the design on track and make sure there is a strong narrative focus.

The method is not without its problems though.

First is that it requires a lot of planning. You need to design a lot of this up front and it’s not very practical to build a scene from experimentation and iteration alone. Design documents are crucial, as there are just too many aspects to keep track of.

Second is that its core strength is also the biggest weakness. The gameplay and narrative are intertwined and if you change one the other needs to be updated too. This mean that you need to throw out and remake a lot more than usual during development. But I don’t see this as a failure, I see this as evidence that the approach really is bringing gameplay and narrative close together.

In a way this approach doesn’t really change the core ingredients of a game. It just adds a bit of trickery on top. This is exactly what I like about it though. It doesn’t rely on anything that we don’t have at our disposal. And, as with all good storytelling, it relies on the audience’s imagination doing the bulk of the work. I am really excited to see how this approach will turn out in the finished games. So far it’s been of great use to us, and hopefully someone else will be inspired to give it a go.(source:gamedev)

上一篇:去接受失衡所提供的变量

下一篇:书摘:以建筑学方法设计游戏关卡

闽公网安备35020302001549号

闽公网安备35020302001549号