从点击操作看基于单位的UI设计问题(上)

作者:Phil Goetz

前言

一般来说,电脑游戏要求玩家控制屏幕上的一个或以上的单位。在早期的游戏中,玩家通常控制只一个单位。随着CPU性能提升,玩家控制的单位越来越多。今天,玩家可能要控制上百个单位,每个都必须独立操作。这种基于单位的UI不再有效了。本文将指出另一种思考UI的角度,讨论如何比较UI的优劣或将一种UI与理论上最有效的UI作比较,最后解释如何改进游戏。我使用的例子主要是策略游戏的,但这些UI案例同样适用于其他类型的程序。(请点击此处阅读本文下篇)

我一直很喜欢《文明》系列游戏。当我让朋友来玩这款游戏时,他们在前一两千年还很有热情——当然这指的是《文明》中的时间,也就是一百多个回合吧。但之后,游戏中城市、单位和等待时间变得太多了,新手就会觉得游戏变成一连串单调乏味的点击操作。

甚至对于资深《文明》粉丝,这款游戏的乐趣也不能超过1800年。点击太多了。我数了我玩到《文明3》的1848年时共经历了多少次点数、鼠标移动和按键盘。许多个小时之后,当那个回合结束,我得到的结果是:422次鼠标点击,352次鼠标移动,290次按键盘,23次鼠标滚轮和18次屏幕滚动。如果不是充分利用了《文明》的所有快捷操作、自动操作和集合移动,以上数字还要翻倍。

你可能会问,为什么我谈的是《文明3》,而不是已经出了好几次个月的《文明4》。我从来没有买过《文明4》。我一直在等着更好玩的《文明》游戏。而我最终等到的是需要同样多点击操作的《文明4》,只是换上了新的3D UI罢了。

不要误解我——《文明4》确实增加了重要的新玩法。在这方面,Firaxis做得比那些只不过制作一些新单位、美术和过场动画就说是新版本的公司好多了。但我不玩《文明3》不是因为我厌烦了那款游戏,或因为它不够精致。我不玩了是因为它需要的时间太长了。《文明》不需要更漂亮的UI——它需要的是更有效的UI。

点击过多不是《文明》专有的问题。即时策略游戏会让你患上更严重的腕道症候群。那就是为什么我不玩《魔兽争霸》或它后来的在线版。对于今天的即时策略游戏,策略似乎变得不重要了,当与你对战的是一个按键比你快两倍的14岁少年时。

RTS的UI从《Total Annihilation》(1997)以后就没有什么突破。这款游戏的单位自动化比现在的许多游戏都更实用。同时,我们的电脑可以控制和动画的对象也增加了,并且还在以指数速度增加。老式UI模型没有达到突破点——更是破了。

本文是关于如何设计一种让玩家用更少的点击传达意图的UI。我不打算讨论UI的人体工学(物理上的易用性)或认知工效学(如视疲劳和人类记忆及处理要求)。在评估他们的UI时,设计者应该考虑到这些问题,但那些太复杂了,不是这么短的文章就能解释清楚的。

“7”原则

策略游戏通常让玩家扮演如军队指挥官这样的角色。但想一想现实世界的指挥官是怎么工作的。他不会一边观察地图,一边命令战场上的每一辆坦克。在真实的战争中,他手下有几个直接听从他的命令的人。在美军中,1个小队长和2名火力小队长一起带领约9名士兵。1个排长通常指挥4个小队长再加上3-4名参谋。1个连长通常对4个排长和参谋直接发号施令。1个中校可能指挥4个连的部队加参谋,等等,形成一个完整的指挥系统。

没有意外。这是使长官得以有效地管理有限数量的下级的军事组织的基本原则。由长官直接指挥的下级数量就是该长官的指挥范围。无论是排长还是战区司令,最有效的指挥范围都是一样的。19世纪欧洲军队确定的指挥范围的最大值是7,这个数字自那以后就没有变过。

在现在的美军中,指挥范围应该是5-7。在救灾工作中,联邦应急管理局的主管监督的下级通常不超过7人。根据美国众议院报告104-631,1997年整个美国政府机构的指挥范围就是7。这并非巧合,7也是一般人可以同时记忆的物品的最大数量。这就是为什么电话号码是7个数字(不含区号)。

这个原则也应该运用于策略游戏设计。控制数量超过7的玩家不可能有效地管理所有单位。(这是推论,如果一个回合历时一分钟,玩家每10秒钟执行移动约一次,那么玩家可能无法专心致志且没有机会进行深入、策略性的思考,而这本应该是策略游戏的乐趣来源。要求玩家每秒一点击的游戏是街机游戏,无论它的复杂度是多少。)

一个战区司令指挥的7个下级通常有一两个不直接参与战斗而是负责转达信息。这意味着不同的信息显示器(游戏邦注:如《文明》中的城市显示和技术显示)计数达到7.

这个原则存在使情况复杂化的因素。以国际象棋为例—-各个玩家控制16个棋子,且同时必须注意16个敌方棋子。这就是为什么国际象棋对初学者来说这么困难。但国际象棋专家却能应付得了。国际象棋的玩法违背了“7”原则吗?

是的,但也不是。国际象棋的专业知识不包括学习用头脑跟进越来越多的棋子;而是学习把棋盘位置拆分成单独的、熟悉的结构——士兵、国王、三个士兵、骑士、一组对中心区域有影响的棋子——为了把概念的数量压缩成人类可控的数量7。

美军的指挥范围目的是,指挥官可以命令和监督第一层级(他的下属),同时跟进第二层级的情况(他的下属的下属)。国际象棋的玩家掌握两个层级的控制:第一,选择这些结构体各自的子目标(比如,“控制中心”或“打破对方的防御结构”);第二,选择执行各个子目标的步法且选择其中一个步法。这样,玩家就不是跟进所有棋子,而是选择每一个步法,这就破坏了“7”原则。如果你希望你的游戏进展得比国际象棋快,且仍然保持策略性,那么你就必须遵守“7”原则。

鱼与熊掌不可兼得

游戏设计师可能会认为,如果允许玩家控制所有单位,但不是必须控制所有单位,那么游戏世界就完美了。不幸的是,事实并非如此。在经济学中有一条法则叫作“Gresham’s Law of Money”,也叫作“劣币逐良币法则”。Gresham解释道,当一个国家使用两种货币,即具有固有价值的金属货币和不具有固有价值的纸币时,纸币会把金属货币驱逐出市场,直到所有人都只使用纸币。

在游戏中,恶劣的玩家驱逐优秀的玩家。在RPG中,糟糕的角色扮演(注重财富积累和控制权的玩法)升级更快,最终把优秀的角色扮演驱逐出游戏世界。在允许控制各个独立单位的游戏中,每秒可以执行3次点击的14岁男性玩家会打败依赖电脑执行其计划的思考型玩家,因为我们距离电脑可以比人类玩家更好地控制单位的时代还很遥远。

有些玩家喜欢快速点击和微观管理,他们也许就是游戏杂志、广告和推广渠道所针对的上述14岁男性玩家。越出这个熟悉的玩家类型的范围总是危险的。任何制作人都不愿意损失这个市场份额,所以游戏最好能够包含独立单位控制的选项。

然而,现在的游戏市场却没有充分考虑害怕患上腕道症候群的玩家(我想这个市场会比14岁少年玩家的市场更大)。如果游戏允许控制独立单位,那么它必定是一个独立的游戏选项,玩家应试能够设置不允许独立单位控制的多人游戏。

现在,你可能会质疑我的神智是否清楚,发布本文的编辑是否有脑子。我是说策略游戏应该只允许玩家控制7个单位?不是的。我是说,玩家不应该直接控制它们。我们必须概念化控制的中间层。这做起来并不困难,只是被常见的对象导向型程序的误解所阻碍。

对象不必是对象

Smalltalk(游戏邦注:为 Xerox PARC在1970年代所发展出来的一种使用功能表单驱动的高级程序语言;常与鼠标器合并使用)用户称对象为“objects”,称方法为“verbs”(动词)。自那以后,许多制作对象导向型程序的程序员都把“objects”解释为“noun”(名词)。我曾与其他程序员争论,因为他们认为游戏不是对象导向的,除非游戏中的物理对象在代码中是OO对象(面向对象)。当我表示,让游戏中的verbs成为代码中的objects,这样组织代码从而强制执行游戏的一致的物理学。他们回答道,“objects就是objects,verbs就是verbs。”至今,我们仍在根据游戏中的物理对象来组织游戏代码和UI。

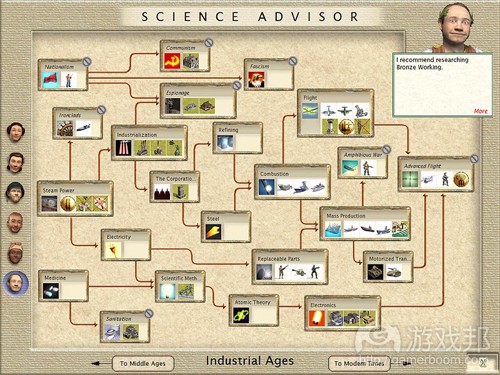

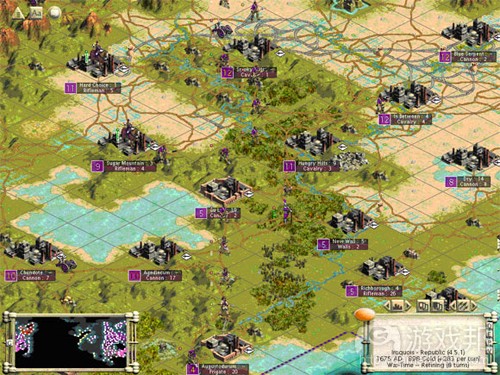

不必如此。对象,在面向对象的情况下,可以是任何你所选择的抽象概念。在《文明3》中,对象可以是军事行为或工程项目。如图1所示。在这张图片中,我的文明已经在开发铁路技术了。我打算把国家的南北两端用铁路连接起来。

对于《文明3》的单位导向的界面,这需要点击各个工人单位,把他们分配到的铁路线路的各个路段。各个工人必须分配到线路的某个短的路段,因为如果你让一个单位从南端作业到北端,让另一个单位从北端作业到南端,那么完的路段就会从他们的任务的开头部分计算,而不会计算另一个单位同时作业的部分——导致大量非重叠的平等铁路线路,以及军队将无法越过你的边界来击退罗马军团的侵略。

为了在被侵略以前完成,我必须分配约一百个工人去建造铁路线。对于各个工人,选中必须点击一次;然后输入“g”开始移动,滚动到铁路线的起点,再点击。之后,当它到达那个点,我必须输入“ctrl-r”以开始建筑铁路和,滚动到那个单位的铁路部分的末端,再点击。每个单位都经过这三次移动,三次按键,和三次鼠标点击。我尝试过把工人组成三人小组,尽管这不是任何时候都可行的。所以我大约执行了600次点击、按鼠标和滚动才完成那条铁路、

想象一下,如果我只要点击铁路的开端和末端,电脑就会指挥工人却建筑他们各自的路段。这整个铁路就会在我指挥各个单位所需的同样的管理工作量下建造完成。

这条铁路的作用是把军队运到边界去抗击罗马军团。另外,每个新建造的单位都必须各自沿着线路运送到边界沿线的某些地点抗击敌人。想象一下,如果我只要简单地确认边界、城市或防御点,电脑就会操作剩下的军队移动,那么我的手腕该省下多少力。但为了清楚地执行,程序员必须把铁路和边界作为第一类对象。(本文为游戏邦/gamerboom.com编译,拒绝任何不保留版权的转载,如需转载请联系:游戏邦)

Too Many Clicks! Unit-Based Interfaces Considered Harmful

by Phil Goetz

Introduction

Computer games traditionally have a player control one or more units on the screen. In early games, each player controlled one unit. As CPU power grew, players controlled more and more units. Today, a player might have hundreds of units, each one of which they must control individually. The unit-based user interface (UI) is no longer sufficient. This article will suggest a different way of thinking about UIs, and will discuss how to compare one UI to another, or one UI to the theoretical maximally efficient UI, to tell if your game can be improved. I’ll use examples primarily from strategy games, but it applies to UIs for programs of all kinds.

Approaching a Thousand Clicks a Turn

My favorite game of all time is Civilization, in all its incarnations. When I introduce friends to the game, they’re enthusiastic for one or two thousand years – which, in Civ, means about a hundred turns. By then the cities, the units, and the waiting have multiplied so much that it becomes, for the novice, a chore more than a game.

Even for a Civ addict like me, the game isn’t much fun after about 1800. Too many clicks. I counted the clicks, mouse movements, and keystrokes that it took me to get through one move of Civilization III in the year 1848. Many hours later, when that turn was done, I’d counted 422 mouse clicks, 352 mouse movements, 290 key presses, 23 wheel scrolls, and 18 screen pans to scroll the screen. This was making full use of all the Civ shortcuts, automation, and group movements. I probably would have made twice as many movements if I hadn’t been counting.

You may wonder why I’m talking about Civ III, when Civ IV has been out for months. I never bought Civ IV. I’d been waiting and hoping for a more playable Civ. What finally arrived was a Civ that takes just as many clicks, but with a new animated 3D UI.

Don’t get me wrong – Civ IV has important new gameplay aspects. Firaxis did far better than companies who create some new units, artwork, and cut scenes, and call it a new version. But I didn’t stop playing Civ III because I was tired of the game, or because it wasn’t pretty enough. I stopped because it takes too long to play a game. Civ didn’t need a prettier interface – it needed a more efficient one.

Overclick isn’t limited to Civilization. Real-time strategy games will leave you with even worse carpal tunnel. That’s why I don’t play Warcraft or its descendants online. In terms of clicking skills, I’m over the hill. Strategy is irrelevant in today’s real-time strategy games when you’re playing against a fourteen-year-old who can click twice as fast as you.

The RTS user interface hasn’t improved since Total Annihilation (1997), which had more useful unit automation than many current games. Meanwhile, the number of objects our computers can control and animate has increased, and continues to increase, exponentially. The old UI model isn’t at the breaking point – it’s broken.

This article is about how to design a UI that lets players communicate their intent with fewer clicks. I’m not going to address UI ergonomics (physical ease of use) or cognitive ergonomics (issues such as eyestrain and human memory and processing requirements). The energetic reader should incorporate those as well into their UI evaluation, but it’s too complex for this short article.

The Rule of Seven

Strategy games typically place the user in the role of something like a battalion commander. But think about the job of a real battalion commander. He doesn’t sit watching a map and barking orders to each tank on the battlefield. In combat, he has a small number of people he gives direct orders to. A squad leader in the US Army leads about nine soldiers, with the help of two fire team leaders. A platoon leader typically commands 4 squad leaders plus 3-4 other staff. A company commander typically gives orders to four platoon leaders plus staff; a lieutenant colonel might command a battalion of four companies plus staff. And so on, up the chain of command.

This is no accident. It is a fundamental principle of military organization doctrine that a commander can effectively manage only a limited number of subordinates. The number of directly-reporting subordinates that a commander has is known as his span of control. The most efficient span of control is believed to be the same for a platoon leader as for a theatre commander. 19th-century European armies settled on seven as the maximum span of control, and that number hasn’t changed much since.

The rule of thumb in the US military today is that span of control should be from 5 to 7. A supervisor in FEMA is supposed to oversee no more than seven subordinates during a disaster-relief effort. According to US House Report 104-631, the average span of control across the entire US government bureaucracy in 1997 was seven. Not coincidentally, seven is also the number of items that the average person can keep in memory at the same time (Miller 1956). This is why phone numbers within an area code are seven digits.

This rule should apply to strategy game design as well. A player who is controlling more than seven entities can’t effectively supervise any one of them. (A corollary is that, if a turn takes a minute, and a player makes a move more than about once every 10 seconds, that player probably isn’t focused and isn’t getting an opportunity for the kind of deep, strategic thought that is supposed to be the source of enjoyment in a strategy game. Games that require a click per second are arcade games, regardless of their complexity.)

The seven subordinates that a field commander controls often include one or two who don’t actually act in combat, but who merely relay information to the commander. This means that different information displays (such as the city screen and the technology screen in Civ) count towards the seven.

There are complications to this rule. Take chess – each player controls 16 pieces, and must be aware of 16 enemy pieces. That’s why chess is so frustrating to a beginner. But chess experts can do it. Are they breaking the rule of seven?

Well, yes and no. Gaining expertise in chess doesn’t consist of learning to keep track of more and more pieces in your head. It involves learning to break board positions down into separate, familiar structures – a pawn structure, a castled king behind three pawns and a knight, a set of pieces exerting influence on the center squares – in order to bring the number of concepts down to a manageable number (say, oh, seven).

The span of control in the US military is intended to be such that a commander can command and supervise one level down (his subordinates), and keep track of everything happing two levels down (his subordinates’ subordinates). The chess player is responsible for two levels of control: first, choosing the subgoal for each of these structures (e.g., “control the center” or “break up his defensive pawn structure”); second, choosing a move to implement each subgoal, and choosing just one of those moves. Thus, it isn’t keeping track of all the chess pieces, but having to choose every move, that violates the rule of seven. If you want your game to play faster than chess, and still involve strategy, you must observe the rule of seven.

You Can’t Have Your Cake and Eat It Too

A game designer might think she can have the best of both worlds by making a game in which the player can control every unit, but doesn’t have to. This, unfortunately, is not so. There’s a rule in economics called Gresham’s Law of Money: Bad money drives out good money. Gresham explained why, when a country tries to use both metal coins that have real inherent value, and paper bills that don’t, the paper money drives the coins out of the marketplace, until everyone is using only paper money.

In gaming, bad players drive out good players. In roleplaying games, the bad roleplayers, who emphasize accumulating wealth and power over playing a role well, advance faster and eventually drive out the good roleplayers. In a game which allows control of individual units, adrenaline-filled 14-year-olds who can make three clicks a second will beat more thoughtful players who rely on the computer to implement their plans, because we’re still a long way from the day when a computer can control units better than a player.

There is a player demographic that enjoys click-fests and micromanagement, and it may be the same 14-year-old males that the game industry’s magazines, advertisements, and distribution channels are aimed at. Trying to step outside that familiar demographic is always hazardous. (I believe games won’t be mainstream until they’re sold at Borders; however, that’s a separate rant.) No producer would want to lose this market share, so it might be good to have individual unit control available as an option.

However, the market of players who do not enjoy carpal tunnel, which I suspect is much larger than the market of 14-year-old males, is not just underserved by today’s games; it is completely unserved. If the game is to also allow control of individual units, it must be a separate game option, and players should be able to set up multi-player games that disallow individual unit control.

By now, you’re probably questioning my sanity and the wisdom of the Gamasutra editors. Am I saying that strategy games should only allow a player to build seven units? Not at all. I am saying that the player shouldn’t control them all directly. We need to conceptualize an intervening level of control. It isn’t hard to do, but is hindered by a common misconception about object-oriented programming.

Objects Don’t Have To Be Objects

Smalltalk users called objects “objects”, and, what’s worse, they called methods “verbs”. Ever since, many object-oriented programmers have interpreted the word “object” as something like “noun”. I had arguments with other adventure programmers in the 1980s who insisted that a game wasn’t object-oriented unless the physical objects in the game were OO objects in the code. When I suggested organizing the code so that verbs in the game were objects in the code, thus enforcing a consistent physics on the game, they said, “Objects are objects; verbs are verbs.” To this day, we organize our game code, and the user interface, around the physical objects in the game.

There’s no need to do so. Objects, in the OO sense, can be any abstraction you choose. In the case of Civ III, an object could be a military action or an engineering project. Consider Figure 1. In this figure, my civilization had recently developed the technology for railroads. I was attempting to construct a railway line connecting the north end to the south end of my civilization.

Figure 1

With the unit-centered interface of Civ III, this requires clicking on individual worker units and assigning them to individual sections of the railway line. Each worker must be assigned to a short section of the line, because if you start one unit from up north toward the south, and another unit from the south toward the north, they compute the path they will follow at the beginning of their assignment, and don’t adjust it to account for the work done in the meantime by other units – leading to a multitude of non-overlapping parallel railway lines, and armies that can’t get to your borders before you’re overrun by Roman legions.

I needed to assign about a hundred workers to building the railway line in order to get it built before being overrun. For each worker, I had to click on it once to bring it into focus; then type ‘g’ to begin a movement, scroll to its starting point on the railway line, and click again. Later, when it reached that point, I would have to type “ctrl-r” to build a railroad, scroll to the end of that unit’s portion of the railway, and click again. That’s three mouse movements, three keystrokes, and three mouse clicks per unit. I tried to keep the workers in groups of three, although this was possible only about half the time. So it probably took me 600 clicks, keystrokes, and scrolls to build that railway.

Imagine if I’d been able to say that I wanted to build a railroad, click on its start, and click on its end. The computer would then have directed workers, as they became available, to work on sections of the railway. The entire railroad could have been constructed with the same amount of supervision that it took me to direct one worker.

The railway was needed to move troops to my borders to defend against the Romans. Again, each new unit built had to be individually routed to some point along the border to defend. Imagine how much less pain my wrists would be in if I could simply define the border, cities, or points to defend, to which the computer would direct surplus troops as they were built. But to implement this cleanly, the programmers would have to have conceived of railroads and borders as first-class objects.(source:gamasutra)

下一篇:如何用BSP树生成游戏地图

闽公网安备35020302001549号

闽公网安备35020302001549号