以“四类画家”分析游戏设计师类型

作者:Shay Pierce

有时候,我觉得自己就是“一脚踏两船”——一只脚在AAA游戏开发世界,另一只脚在独立游戏开发世界。所以我观察这两个领域的视角总是很有意思……

几天以前,Bungie首次公开他们的游戏《天命》。我的朋友兼前合作者Josh(正在制作《天命》)在Twitter上表达了他的沮丧。Josh是独立游戏的铁杆粉丝,他感到泄气是因为他尊敬的许多独立游戏开发者似乎非常不看好这款游戏。

我当然理解Josh的失望。毕竟,他知道参与制作《天命》的都是有创意有才能的人,并且这款游戏中确实有亮点。它是无数才能和工作的结晶。然而,有些人甚至还没看到游戏的真实情况,就开始鄙视它了。

我已经发现,“独立视野”也可能与“游戏势利”大量重叠。我对自己的游戏总是很挑剔,基本上是因为我玩游戏太多年了,只有真正有创意的游戏才能让我感到惊喜。但我确实不认为我对游戏的品味就必然比别的人“更高”或“更低”,所以我才没有变成真正的“势利眼”;萝卜青菜各有所爱,并且个人的品味也是不断提高的。

Greg Costikyan曾经提到这个话题,除了让我大开眼界,也总是提醒我视野要开阔,要博览各种艺术形式,要适应不同的品味:

我的部分目标是,促进“心胸开阔的玩家”的美学,我能够发现人们在所有游戏中感到美的东西;但那是因为我是游戏设计师和自命不凡的“游戏鉴赏家”。大多数玩家倾向于寻找他们喜欢的游戏,通常贬低他们不喜欢的游戏,即使他们不喜欢的游戏很受其他人的欢迎——我爱的游戏是经典,你爱的游戏是垃圾,二者永无交集。如果你不喜欢《最终幻想》,你显然就是个白痴;或者相反的,你沉浸于游戏的故事,却不理解什么才是游戏,你显然就是个傻瓜。这就是目光短浅的表现。

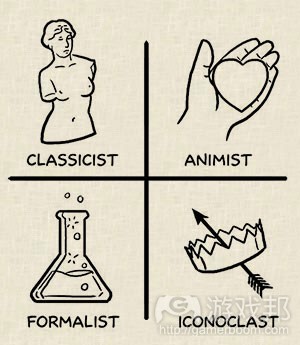

我一直在思考Scott McCloud(漫画书作者和理论家)提出的“四类画家”。他在《漫画制作》一书中提出这个理论。我在网上找到了一篇关于这个理念的一篇好文章。以下是其对这四种类型的主要描述:

1、古典派:这类画家看重手工技能,并且精通艺术形式。他们的目标是创作一种能够体现传统美学原则的永恒的艺术作品。完美是不可能达到的,但那并不意味着他们就不会追求完美。根据McCloud的说法,他们的关键词是美,他们是荣格人格论的“感知型”。

2、灵性派:这类画家对内容感兴趣。他们的目标是清楚地表达他们的故事或想法。一定程度上,媒介必须总是与信息互动,但灵性派对内容的专注意味着他们尽可能让形式透明。他们的关键词是内容,McCloud认为他们是荣格人格论中的“直觉型”。

3、形式派:这类画家痴迷于他们所选择的媒介形式。他们创作是为了探索艺术形式的边界和轮廓,以理解其功能和内部运作方式。他们的艺术作品具有实验性,他们通常也是艺术分析批评家。他们的关键词是形式,McCloud将其对应为荣格人格论中的“思考型”。

4、革新派:这类画家强调真实和艺术经验。对他们而言,艺术必须是美的,必须反映生活。他们认为艺术的使命是掩盖生活中的缺陷和失落。提倡“诚实”或“返朴归真”的画家正是反映了革新派的思想。他们的关键词是真实,McCloud对他们的分类是荣格人格论中的“体验型”。

那篇文章还探讨了如何将这组概念运用于数字游戏领域。但我认为它还不够深入,它过分强调“放弃创作者的权威”,对我而言,这与游戏的本质无关。为了讨论游戏到底是什么,我认为最好不提创作者权威的问题,因为这会使我们在讨论游戏时误把它当成叙述媒介的核心,而事实上它并不是。游戏设计最好能类比成建筑学——没人会问,Frank Lloyd Wright(游戏邦注:他是20世纪最具独创性的美术建筑师)允许人们在他的作品中移动,是否放弃了创作者的权威。

所以我认为读者们应该思考一下根据Scott McCloud的框架,不同的游戏设计师应该如何分类?为什么?注意,大多数画家都有一个“主要的”和“次要的”倾向——就像荣格的原型论所说的。

特别是,McCloud定义的“艺术/生活”的频谱存在于游戏中吗?如果存在,你认为它的特点是什么?我对游戏中的这个频谱是什么有直觉上的理解,但我无法准确地定义它。

我认为Edmund McMillen(《超级食肉男孩》和《Binding of Isaac》的设计师)主要倾向是灵性派,次要倾向是革新派:他关注制作大量优秀的内容;但他也有真实地表达自我的强烈愿望。同时,我认为我的朋友Davey Wreden(《斯坦利的寓言》的制作者)可能是纯形式派,他专注于摆弄形式和探索形式的边界……小岛秀夫(《合金装备》的设计师)可能至少是半个形式派。

(至于我本人,我认为我至少是半个形式派,可能是因为我喜欢思考/撰写/讨论形式吧!)(本文为游戏邦/gamerboom.com编译,拒绝任何不保留版权的转载,如需转载请联系:游戏邦)

Game Designers and the Four Tribes of Artists

by Shay Pierce

I sometimes feel that I have one foot in the AAA development world and one in the indie game development world. It gives me an interesting perspective on both sides…

A few days ago when Bungie did their first reveal of “Destiny”, my friend and former co-worker Josh (who is working on Destiny) was expressing some frustration on Twitter. Josh is a big fan of

indie games, and was frustrated because many of the indie game developers he respects were seemed to be expressing immediate disdain for the game. Here’s a link to the Twitter conversation that ensued, which I found interesting.

I’m sure it’s frustrating: he knows that there are innovative, brilliant people working on Destiny and that it’s something beautiful and worth making. An incredible amount of talent and work is

going into the game. Yet some people are poo-poo’ing it before they really even know what it is.

I’ve certainly found that the “indie scene” can have a lot of overlap with “game snobbery”. I tend to be very picky about games myself, though I mostly think it’s because I’ve been playing games for so long that only the most innovative and novel games tend to surprise and interest me. But I don’t really think of my taste in games as inherently “better” or “worse” than anyone else’s, which I think saves me from actual snobbery; everyone has their own taste and everyone’s taste evolves.

Greg Costikyan gave a talk once, and touched on this point; it was eye-opening for me and has always reminded me to keep an open mind about the massive breadth of our art form and the range of different tastes it can accomodate:

Part of my objective in general is to foster the aesthetic of a “broadminded gamer,” able to see what people find appealing in any game; but that’s because I’m a game designer and pretentious

“ludeaste” (a word I just coined by analogy to cineaste). Most gamers prefer to find games that they like, and often look down on ones they don’t, even if enjoyed by others. My games rock; your games suck, and never the twain shall meet. If you don’t like Final Fantasy, you’re obviously an idiot, or conversely, sucked in by the story and don’t really understand what games are really about. This is a short-sighted view.

Since my Twitter exchange with Josh, I’ve been thinking a lot about Scott McCloud (the comic book creator/theorist) and his “4 tribes of artists”. He lays out this theory in the book “Making Comics”. Here’s the best writeup I’ve found on this concept, and I encourage everyone to read it. Here’s the core description of the four types:

The Classicists admire craftsmanship and mastery of the artform. Their goals include creating lasting works of art which adhere to traditional aesthetic principles. Perfection is impossible, but that doesn’t mean they can’t try for it. According to McCloud, their catch-word is beauty, and they are an extention of Jung’s sensation archetype.

The Animists are interested in content. They aim for the clearest presentation of their story or ideas. To some extent the medium must always interfere with the message, but the animist’s focus on the content means they try to make the form as transparent as they possibly can. Their catch-word is content, and McCloud considers them an extention of Jung’s intuition archetype.

The Formalists are fascinated with their chosen medium’s form. They create their art to explore its boundaries and contours, to learn what it can be capable of and how it works internally. Their works of art incorporate experiments, and they often double as analytical critics. Their catch-word is form, and in McCloud’s scheme they correspond to Jung’s thinking archetype.

The Iconoclasts value truth and experience in art. To them art must be authentic, must show life as it is. They take aim at artistic conventions that gloss over the imperfections and disappointments at life. Artists who speak of “honesty” or “rawness” are voicing iconoclastic ideas. Their catch-word is truth, and they are Jung’s feeling archetype.

That article even touches on how the concept could be applied to digital games. But I don’t think it goes far enough, and its fussing over “abdicating authorship” is, to me, beside the point of

what games are. For discussions like this, I think it’s best to avoid the authorship question because it leads us to discuss games as if they were a storytelling medium at their core, which they’re

not. Game design is better compared to a field like architecture – no one asks whether Frank Lloyd Wright was abdicating authorship by allowing people to move through his buildings however they wanted.

So I think I’ll leave it as a challenge to the Gamasutra community: how would you classify different game designers within Scott McCloud’s system, and why? (Remember that most artists have a “primary” and a “secondary” tendency – just like Jungian archetypes.)

In particular, does the “art/life” spectrum that McCloud defines exist in game design? If so, how would you characterize it? I feel like I intuitively understand what this spectrum is within

gameplay, but I’m not yet able to define it precisely.

I’ll start things off by defining Edmund McMillen (designer of Super Meat Boy and The Binding of Isaac) as an Animist first and an Iconoclast second: he cares about creating great Content

prolifically; but he also has a strong need to express himself in a raw and True way. Meanwhile my friend Davey Wreden, creator of The Stanley Parable, might be a pure Formalist, focused on playing with the Form and exploring its boundaries… Hideo Kojima is probably at least partly a Formalist as well.

(For myself, so far all I’ve figured out that I’m at least partially a Formalist, which perhaps is obvious simply from the fact that I’m willing to think/write/talk about this stuff ad nauseum!)

(source:gamasutra)

闽公网安备35020302001549号

闽公网安备35020302001549号