分析故事叙述中的“强加空间”和“表达空间”

作者:Raph Koster

我所说的故事叙述不是游戏机制,而是反馈形式是指,故事是作为完成特定任务的奖励。从根本来说,游戏主要围绕任务的执行——实现目标,无论是自己设定的,还是设计师强加的。它们主要涉及解决问题,是关于各种复杂问题的认知把握模式。

有人以“内容”形容故事叙述所扮演的角色。但我不会用这个词语形容各种反馈信息。

换而言之,这听起来有些顽固——我通常不会将系列故事元素称作“游戏内容”。但我其实有时也会这么做,甚至还会基于此设计游戏。

通常我们对于“内容”的定义是,“代码或规则以外的所有元素”,是指所有美工、旁白、任务及其他琐碎元素。但这不是内容在本文中的含义,因为这里我们要进行另一形式主义的分析。

我之前曾将自己用于分析游戏的基本模式称作“游戏语法”,这非常符合“语法”的形式定义。这一模式(游戏邦注:或称作游戏设计的原子模式)同游戏的形态学联系紧密:它们所采取的结构和形式。这基于Chris Crawford的创造性著作,他将交互作用定义成:

两个演员交替倾听、思考和说话的循环过程。

——Chris Crawford《The Art of Interactive Design》

游戏语法模式的运用方式和所有交互作用相同。游戏互动存在的主要差别是,某个演员也许是个规则系统:计算机或系列规则和流程。从根本来说,游戏主要围绕探究对手所运用的规则和步骤;对手也许是计算机,也许是真人,或者甚至是物理规则及你自己身体的体能限制。你的任务是判定目标,设法找到同此机制互动的方式,然后获得预期结果。

谈到游戏机制,我们所指的是游戏的集合。一个系统通常是由各种机制构成,而每种机制则又由不同规则组成。不同人对于这一机制有不同的定义,有的是“趣味颗粒”,有的是“原子”,有的是“ludeme”。

但系统有点像运算规则或印刷机。它重复执行同个流程,但由于应对的元素不同,你可以从中获得不同体验。这里的“所应对的元素”就是指内容,而多数时候它指的其实是“数据变化”(游戏邦注:如包含不同统计数据的敌人,包含不同平台设置的关卡)。

有类游戏主要围绕用户生成的故事叙述,而不是设计师设定的内容——我曾在之前的谈话中谈及二者的差别。我在谈话中的观点是:

这些空间依然能够叙述故事。我们放弃的不是故事叙述,而是控制权利。

我自己创造了新术语“强加空间”和“表达空间”,以此定义两种极端情况。

这个谈话先于各个具有可行性的游戏语法之前。但事实上,我批评故事叙述游戏快速点击操作和过多反馈信息的文章主要围绕强加空间,及游戏设计师强加的故事元素;这主要是基于“开玩笑”的口气。有人批评我忽略其中的表达空间及旨在充当故事叙述推进因素的空间内容。

故事碰巧也包含些许规则,主要基于大脑的运作方式。例如,《The Art of Fiction John Gardner》就完美体现这点:反复提及实体对象如何令其同情感元素联系起来——其实是变成符号标记。提及同这些物体相关的物体也是如此。从某种意义上来说,主题内容具有传递性。

这一技巧被广泛运用至各种媒介中。例如,Ravel的《Bolero》由于影片的缘故和性紧密联系起来,现在只要播放此音乐我们就会产生此联想。

游戏的表达空间广泛采用此技巧。其实玩家叙述的各种文字内容也是如此。它们将意义归结到各个时刻,然后玩家就会基于他们对事件的选择性记忆建立起故事叙述脉络。我经常将其称作编造虚拟故事,我们经常会不自觉地这么做。

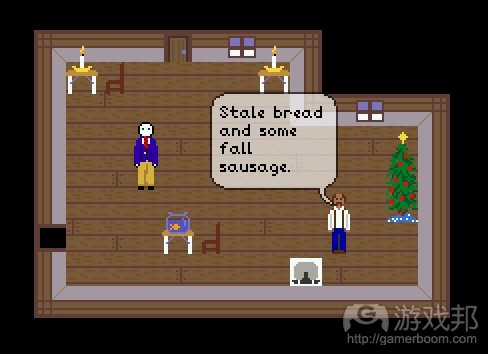

那些旨在让玩家拼凑故事内容的游戏,例如《Sleep is Death》、《Facade》或《Dear Esther》,通常会融入系统和算法元素(游戏邦注:因此也会包含数据变化)。数据变化内容其实是较小的标记和叙述时刻,通常属于印象主义风格或缺乏连贯性。玩家面临的“问题”是将它们组成连贯的整体。

标记、特定时刻及记忆属于无形内容,但这并不意味着我们无法对其进行组合;正如我们看到的,虚构内容也能够组成连贯的整体。但从机制角度来看,它们和手中持有的牌或Scrabble方格存在许多共同之处。你通过理清它们的意思终止同系统之间的互动,这和单纯基于等级在方格中拼出单词截然不同。Dear Esther的机制可以复制到不同背景和标记组合中——起到不同的情感效果。通过游戏语法进行分析,我们会发现两种不同体验其实属于同类游戏。

下面就来进行一个思维试验。

我从曾和若干设计师同行进行交谈,他们中有人正在尝试有关记忆的游戏。我提出一个这样的游戏构思:设计一个有关房子的地图,然后植入一副牌,在每张牌上标记“复述的扶手椅”、“深入的壁橱”和“空荡的书架”之类的文字。将牌组弄乱,在每个房间中各放几张。

玩家依次抽取纸牌,讲述有关纸牌文字的“回忆”及其在房子中的位置。你记得自己曾缩在扶手椅上看书,这是个安全而舒服的回忆;另一位玩家则说自己的外祖母是在扶手椅上死去的。所以回忆都必须具有“真实性”——这意味着,这不能同他人所述内容相抵触。在叙述完所有故事后,玩家可以通过投票选择自己希望以什么方式回忆扶手椅。

被选中的玩家将保管这张纸牌。待到游戏尾声,持有最多纸牌的玩家就胜出。

要获得更大的情感冲击性,你可以选择和家人,基于自己家里的布局和童年物件体验这一游戏。

这里我们拥有意外的共识故事及游戏系统。回忆其实是游戏空间中的符号——无形元素,其带有众多情感含义。你可以基于机制角度处理游戏,制定相应策略。但你也可以凭借经验进行操作。这主要属于表达空间。从根本来说,游戏主要围绕对自己家庭和历史的把握。这依然属于模式配对,涉及互相了解彼此、复杂关系网络及构成家庭历史的本真半假叙述和主观回忆。

在这款游戏中,

* 故事叙述是输入内容——给予玩家的启示信息,“他们所能采取的举措”。

* 故事叙事是资源——逐步积累,朝获胜目标迈进。

* 故事叙述其实属于用户生成内容,会给系统带来数据变化。

* 故事叙述属于反馈信息——是基于个人符号形式积累而成,代表“游戏状态”的完全形态。

但这还算不上游戏机制。事实上,你可以将回忆替换成五颜六色的扑克牌筹码,所有内容依然会以同样方式继续进行。但从本质上来说,体验将变得截然不同,情感冲击将降低很多。

你可以去除其中的游戏成份。不要让玩家投票决定谁的回忆故事将胜出,不要融入不能发生抵触的规则,你只是简单享受查看相片簿的体验——同样,你无需应对把握前进规则的挑战。

前面我有说到,故事叙述不属于游戏内容。讽刺的是,故事叙述属于内容的游戏通常有非常复杂和稳固的规则系统。Chris Crawford的《Storytron》的制作过程历经数年之久,主要围绕于系统设计。《Facade》是AI方面的创举。就连这款小型非数字游戏都“输入”众多关于心理元素和过去家庭历史的规则,以及容易违反的规则。

因此我能够轻松协调“游戏学”形式主义和将游戏视作故事的叙述学模式之间的分歧。我在小机制大反馈模式游戏中的问题主要和缺乏实际模式学习过程及缺乏玩家代理关系有关,这使得游戏无法呈现高质量的内容。我在其中融入意外故事叙述游戏和表达空间,我将此视作游戏——这其实比很多游戏更复杂。所以对于那些觉得我抹黑整个意外故事叙述游戏题材的人士,我在此对自己的表达不清致歉。

那么这将设计师强加故事置于何处?主要是在互动体验设计的领域中。这是个和“游戏设计”截然不同的学科(游戏邦注:虽然它们有很多重叠之处)。我提倡正确把握游戏设计,但这并不意味着互动体验设计本身不是个有趣而深刻的领域——或者这对游戏来说毫不重要。事实上,这非常重要,但这并非本文讨论的话题。(本文为游戏邦/gamerboom.com编译,拒绝任何不保留版权的转载,如需转载请联系:游戏邦)

Narrative isn’t usually content either

When I said that narrative was not a game mechanic, but rather a form of feedback, I was getting at the core point that chunks of story are generally doled out as a reward for accomplishing a particular task. And games fundamentally, are about completing tasks — reaching for goals, be they self-imposed (as in all the forms of free-form play or paideia, as Caillois put it in Man, Play and Games) or authorially imposed (or ludus). They are about problem-solving in the sense that hey are about cognitively mastering models of varying complexity.

Some replies used the word “content” to describe the role that narrative plays. But I wouldn’t use the word content to describe varying feedback.

In other words, perverse as it may sound, I wouldn’t generally call chunks of story “game content.” But I would sometimes, and I’ll even offer up a game design here that does so.

The usual definition of “content” is “everything that isn’t code or rules,” meaning all the art and voiceovers and quests and whatnot. But that’s not what it means in this context, because we’re embarking on another one of thse annoyingly formalistic exercises here.

I have previously described the basic model I use for analyzing games formally as “a game grammar.” This was mostly a conceit for a presentation title, but in point of fact it fits the formal definition of “grammar” moderately well. You see, this model, which I have also termed an atomic model of game design, is concerned exactly with the morphology of games: the structure and form they take. It builds on the seminal work of Chris Crawford, who defined interaction as

a cyclic process in which two actors alternately listen, think, and speak.

– Chris Crawford in The Art of Interactive Design

The game grammar model works the same way as all interaction does. The chief difference with game interaction is that one of those actors may actually be algorithmic: a computer, or a set of rules and processes. At core, a game is about figuring out the rules and processes that an opponent is using; said opponent might be a computer or a real person, or even the laws of physics and the physical constraints of your own body. Your job is to identify a goal (which might be handed to you by a designer, or might be one you set for yourself) and attempt to arrive at a way of interacting with this system that results in the outcome you want.

When we speak of a game system, that collection of rules is what we mean. Usually a system will be composed of multiple mechanics, each of which is made of up a variety of rules. A system like this has also been termed a “fun molecule,” an “atom” or a “ludeme” by various authors.

A system, though, is sort of like an algorithm, or a printing press. It repeatably performs a process, but given different stuff to work with, you can get a pretty different experience out of it. The term for the “stuff to work with” is content, and most of the time it is effectively “statistical variation.” An enemy with different stats, a level with different placement of platforms.

There is a class of games that focuses on user-generated narratives rather than on authorially imposed ones — you can read about the distinction in a very old talk called “Two Models for Narrative Worlds” I gave at the Annenberg Center at USC. In that talk I made the point that

These worlds can still tell stories. What we surrender is not narrative, but authorial control.

I coined the terms “impositional space” and “expressive space” to define the ends of this spectrum for myself.

Now, that talk long predates any of the game grammar sort of work. But effectively, my critique of quick-time-events and excess feedback used in narrative-driven games is primarily about impositional spaces, narrative imposed by the author(s) of the game; and it is essentially in a “ludic” context. And several folks took me to task for ignoring the expressive spaces and the spaces that are intended to serve as narrative generators in that critique.

Story, as it happens, has some rules too, largely based on how the brain works. For example, in The Art of Fiction John Gardner has a wonderful example of the ways in which repeated mention of physical objects causes them to become associated with emotions — in effect to become symbols. And then mention of objects associated with those objects does the same. In a sense, thematic freight becomes transitive.

That particular trick is used very very widely in all sorts of media. For example, Ravel’s Bolero has become thoroughly associated with sex thanks to the film 10, and now at this point you can conjure up that association by just playing that music.

Expressive spaces in games rely on this trick extensively. In fact, all forms of post facto storytelling by players do. They ascribe meaning to moments, and then the player builds a narrative arc through their selective memory of events. I often call this mythmaking, and we do it pretty much all the time, without even thinking about it.

In games designed to cause the player to put together stories, such as Sleep is Death, Facade, or Dear Esther, there is a system there, an algorithm — and then there is the statistical variation that is fed into it. And that statistical variation, the content, is actually little symbols and narrative moments, ones that are often impressionistic or disconnected. The “problem” the player faces is that of arranging them into a coherent whole.

The fact that symbols and moments and memories are profoundly intangible things does not mean that they can’t be manipulated in this way; fiction does so readily, as we have seen. From a mechanical point of view, though, they have much in common with the particular hand of cards you have been dealt, or the set of Scrabble tiles on your rack. You end your interaction with the system by making sense of them, which is different from finding a word in the tiles only by a matter of degree. Dear Esther‘s mechanics could be replicated with a different setting and group of symbols — to radically different emotional effect. When analyzed by the game grammar, we’d find two very different experiences to be the same game.

Let’s consider a thought experiment.

I was once in a discussion with some fellow designers and one of them was playing with the idea of a game about memories. I offered up a design idea whereby there was a map of a house, and there was a deck of cards, each card labelled things like “comfy armchair” and “deep closet” and “empty bookshelf.” The deck was shuffled, and some cards were laid in each room.

Players would then take turns tapping a card and telling a “memory” about that card and its place in that house. That this was the armchair where you remember curling up to read, a memory of safety and comfort; and another player says it was where they found great-grandmother when she finally passed away. All memories must be “true” — meaning, they cannot contradict anything anyone has said. After all stories were told, all the players decide which way they want to remember the armchair from among the stories told, by voting.

The person whose memory was selected keeps the card. At the end of the game, whoever has the most cards wins.

For greater emotional impact, you play this with real family, a real house layout, and real objects from your childhood.

Here we have both emergent consensus narrative and a game system. The memories are actually tokens in the game space — intangible ones, with a lot of emotional weight to them. You can approach the game mechanistically, and strategize. But you can also approach it experientially. It is mostly an expressive space. And ultimately, the real game lies in making sense of your family, its history. It is still pattern-matching, grokking each other and the complex web of relationships and half-truths and biased recollections that make up a family history.

In this game,

* narrative is input — the affordance given to a player, the “move they can make”

* narrative is a resource — accumulated and managed towards a victory condition

* narrative is actually content, user-generated even, providing statistical variation into the system

* narrative is feedback — its accumulation, in the form of individual symbols, is representing the gestalt “game state”

But it’s still not a mechanic. You could in fact replace the memories with differently colored poker chips, and everything would proceed in the same manner. The experience would be substantially different, and the emotional impact far less.

You could also de-game this. Don’t negotiate whose memories win out. Don’t have the rule about non-contradiction. You’d end up with the experience of looking through a photo scrapbook — and likely, you would not tackle the challenge of understanding that the rules push you towards.

This game has never been played. If anyone ever does, let me know what happens.

In the post title I said that narrative isn’t usually content. This game is an exception, as are the other ones I have cited. Ironically, games where narrative is content actually tend to have very very complex and robust rule systems. Chris Crawford’s Storytron has years of development in it, almost all in the systems design. Facade is an AI wonderment. And even this little non-digital game has as “imported” rules a host of psychology and past family history, rules that are deeply perilous to transgress. (The mere addition of other players always imports complex social rules into a game; in this case, the deeply personal nature of the interaction brings in yet more. “We never talk about her drinking problem” and the like).

Because of this, I have no issue reconciling formalism in examining the “ludology” of games with the “narratological” approach of examining games-as-stories. My issues with small-system-big-feedback games described in the other post have to do with the lack of substantive pattern-learning, the lack of player agency, and thus the lack of the fundamental qualities that games bring to the table. And in that, I include emergent-narrative games and expressive spaces, which I certainly consider games — more complex games, in point of fact, than most games are. So for those who felt I was bashing the entire genre of emergent narrative games, I apologize for the lack of clarity there; that was not at all where I was going with that post.

So where does this all leave authorially imposed story? Primarily in the realm of interactive experience design. Which is a different discipline from “game design” though they have tremendous overlap. I am biased towards our getting game design right, but that does not mean that interactive experience design isn’t a fascinating and deep area in its own right — or that it is unimportant to games. In fact, it’s incredibly important. But that’s a subject for another post someday.(Source:raphkoster)

闽公网安备35020302001549号

闽公网安备35020302001549号