专家称心理学研究有助于开发富有黏性的游戏

游戏邦注:本文是心理学研究者和作家Neils Clark对游戏开发过程中的心理学原理说明,他认为通过研究心理学可以开发出让用户沉浸其中的游戏。

游戏的核心在于乐趣,心理是乐趣的试金石。本文将就心理学中对创造黏性高,有吸引力的游戏体验中最为有效并能够立即应用的方法进行讨论。从构建难以抗拒的奖赏系统的行为学方法,到产生需求的动机理论,以及像心流这种混合理论,游戏公司不必再因财政问题而回避心理学。让我们这就开始吧。

心灵最先寻求愉悦

行为学家说 – 愉悦为先,然后,避免痛苦,形成了我们所要做的每一步行动。这也许听起来老生常谈,或有还原主义倾向,直到我们认识到生活中的大部分奖赏和惩罚都因为过于微小或随着时间的流逝而被遗忘。

不论我们是否了解,是否喜欢,行为都由奖赏构成。通过行为准则,心理学家才能训练出会弹钢琴,打乒乓球,以及准确定位溺水者并爬上海滩救援直升机的鸽子。

操作条件反射,通常跟爱德华•桑戴克和B.F.斯金纳绑在一起,研究如何通过奖赏增强任意行为。

通过奖赏加强行为有两种基本方式:带来愉悦,或回避痛苦。分别为积极的巩固和消极的加强。还有惩罚,惩罚带来剧烈的后果,但是没有必要移除首先强化行为的方法。

并不是所有的奖赏都在同等条件下产生的。被称为首要强化条件,是因为它们是最为无意识的强大并依赖于本性;比如睡觉,视觉惊奇或性。

让我们谈论一下性。不管玩家是否意识到,在生理上有吸引力的角色将会充当本能的积极的强化方式。从另一面讲,让玩家回避视觉上令人不舒服的角色或形象作为本能的奖赏是消极的强化条件。如果我们在意为玩家提供愉悦和乐趣,那么我们首先要做的就是最大化首要强化条件。

尽管通过首要强化条件奖赏我们自己需要付出一点精力,我们通常将它们同其他刺激因素相关联。斯金纳理论的先驱 – 经典条件反射理论,会将本能的愉悦称作非条件性刺激,因为它们不是自发的。没有必要的关联。

对我来说,强大的关联来源于电影《宿醉》中的一个场景,在Phil Collin的著名乐章《In the Air Tonight》响起,Mike Tyson同Zach Galifianakis共度时光。 如果你并不期待它(如果期待,那么这一感受就会加倍),就是新的视觉刺激,并激发了本能的身体上的回应。

《In the Air Tonight》现在对我来说是一个反射性刺激。我等着整首歌,脑中想着那个片断,由于视觉关联通过特殊的奖赏产生条件性的反应。在经典条件反射理论中,奖赏等级通常由时间(上面的场景为配合音乐而计算好了时间),本能刺激的强烈程度(Tyson是个热情的人,但有些人也许根本不会注意到这个场景),以及将这两个刺激条件配对的频率(你看过多少次《宿醉》?)而支配的。

在配对条件满足之后,大量的奖赏成为了第二级的强化条件。金钱,物物交换,称赞,成就,尽管对关联中哪些要素会变得具有吸引力并没有什么限制,但我们想要首先利用文化上流行的强化条件。金钱是任何西方市场中对游戏开发的有力要素,因为我们的确能够通过金钱提升游戏黏着性。

尽管并不是杀每个怪或者为设备升级的活动都那么有趣,但这两项都带有万能的奖赏要素。正如麦当娜曾经说过:“有钱的男孩总是Mr. Right。”虽然有些设计对于二级条件来说太过抽象,但运用文化假设的确能够让强化条件更加明显和有力。它让游戏有趣。

但是有趣的游戏并不就是将金钱,物品或本能奖赏抛给玩家;它会在经过衡量和考虑的安排下而传送给玩家。基本上,行为心理学为我们提供了健康平衡的奖励调度的五个基本构成。首先是持续的强化操作。在每次玩家进行了我们想要看到的行为时都加以强化。我们甚至会持续进行强化让行为逐步接近我们想要看到的,行为学家称之为形成。

持续强化并形成的典型案例是《魔兽世界》,抛开种族和等级不谈。学会恰当的行走,有效地厮杀,技能运用,战利品,买卖等等,不吝啬赞扬,经验和现金价值。然而,持续的强化是最先会消逝的,因为玩家立即会注意到你停止了奖赏。

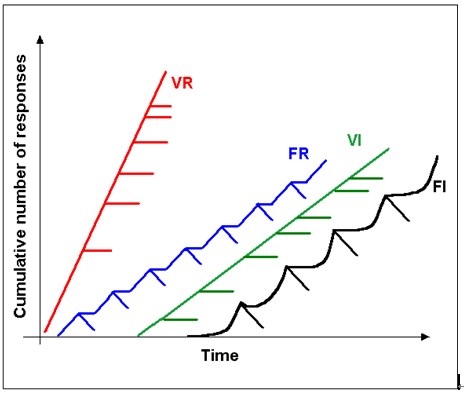

因此,我们还要以比率和间隔对奖赏进行分布。有时候这些是修正的比率(Fixed Ratio – FR)或修正的间隔(Fixed Interval – FI),只有在一组正确的回应下才进行奖赏,或在一组时间后进行奖赏。我们也能运用可变换的比率(Variable Ratio – VR),或可变换的间隔(Variable Interval – VI),分别在曲折达成的一系列正确反应后,以及曲折积累的一定时间后进行奖赏。伴随着持续的强化,这首要的五个要素组成了简单调度最为通用的部分。

变量比率以其效果和持续性为标注。注意,这类表格在涉及FR和FI时会变化。某些时候,FR被描绘成比所表述的更多的刺激,FI则被描述成比所表述的更少的刺激。

大多数人也许是在复合奖赏调度下进行游戏(尽管未曾注意到)。假设你需要100个食尸鬼肢体(为了任务)。首先你要在三堆食尸鬼尸体的其中一堆找到肢体。然而不久之后,你就只能每两分钟找到一次肢体,随后是每5个食尸鬼中找到一个,然后你要从每个该死的食尸鬼身上抢夺,但这不会花太长时间。

最后,一旦你拥有了95组食尸鬼肢体,我们假设,你就只能在每三分钟左右找到一个了。注意这不是纯粹的推测。在关联中使用简单的调度非常常见,正如以上例子所讲的。

如果任务发布者实际上为我们提供一些奖赏条件的暗示,比如“就杀死6个食尸鬼”,那么,“好的,现在每分钟杀死一个,持续15分钟,这会很好,”等等,一直到在末尾出现肢体主体的奖励,行为心理学也将这称作锁链。如果你想更深入的了解复合排期,维基百科(通常来说)是个很好的开端,尽管(通常来说)它不总是那么学术。

对于游戏设计,行为心理学鼓励植入并存的奖赏调度。它们让我们的大脑挑选奖赏自己的最佳方式。在玩家大脑中产生乐趣的关键在于满足他们的需要。他们应该总是具备如何刺激自己的选项。不要让令人厌恶的情况干扰他们。我们已经了解了我们正在逃离的世界。

正如伟大的Frank-N-Furter博士所说,“给自己绝对的愉悦。”

尽管对这样做了如指掌。它会,例如,让获取愉悦的能力休息片刻并再一次,正如本文中所提到的享乐适应。良好构建的奖赏也许会让我们自己去实现有所困难,因为我们首要影响动机的神经化学物质,多巴胺,已经显示出,同欲望或“探索”相比,愉悦的成分更少。

我们的大脑随着时间的流逝而进行结构上的改变,这一过程称作可塑性。尽管我们在最初几次受到新的刺激时,多巴胺会分泌出感到快乐的成分,不久之后,我们重新接收并感受这些一次新奇的刺激的需求。奖赏随后开始引起同食物,性,压力等等相同的动机神经电路反应。因此游戏必须让他们更进一步理解这一神经电路,就像行为心理学,他们应该紧随步调。

爱的定义

现在让我们看看玩家的深层次需求,渴望,以及爱。不是去探索行为的奖赏,动机的理论所要求的是我们最理想的刺激程度,以及驱使我们寻找特定体验的要素。弗洛伊德列出了第一个本能动机的列表,不出意料的由攻击性和两性的推动组成。

威廉•詹姆斯的列表更为丰富,包括竞争(或对抗),好战,(愤怒和不满),同情,猎奇,奇怪的人和物(新奇),(害怕)黑色的东西或阴暗的场所,偷盗,害羞,嫉妒,清洁等等。这些本能的问题经过多年以及多位理论学家之手,列表难于控制的膨胀了。

同行为学家一样,动机理论学家开始以首要(天生的)和二级(学到的)驱动来区分并分析这些本能。驱动理论认为,所有的动机都是寻求自我平衡。

从生物学上讲,我们维持血糖和体温,但是一旦每件事都井然有序,我们似乎还有需要测试新奇刺激并寻求激发等级的本能。我们会推崇简单的动机,例如“开放的草原,奔驰的骏马,猎鹰站在你的手腕上,风吹过你的头发。”

但也许佛洛伊德更接近事实。性和行动是固有的,生物的“推动”,在能够做到的时候会从本能上感觉更好,“碾压你的敌人,看着他们在你面前逃跑,听他们的女人的哀号。”

感知寻求者会追求超高等级的刺激和危险,虽然这些人会在他们想要的具体程度上有所变化。

在推动之上添加重要的对激励,社会需求,和自我实现的“拉动”。我们从子宫中出来时可没有要每隔5分钟通过我们的3G Droid应用鸣叫一次的需求,尽管过去的奖赏和好的关联告诉我们这样做让我们的大脑快乐。

我们的大脑在对快乐产生不满时会有助于改变我们的信仰和价值观。这一紧绷状态被称为认知不协调,像“吸烟并不那么坏”或“我家族中没有癌症,”是自然的人类对其反应的例子。比如“通过我的庆典游戏并不是件大事,”或“我的婚姻已经出现了问题。”感谢这些认知不协调的反应自然而然的消除了令人厌恶的不舒适,有助于我们保持正轨并让人类持续的寻求乐趣。

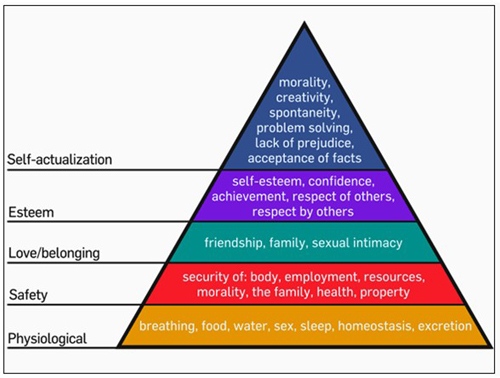

亚伯拉罕•马斯洛提出的著名的人类动机理论,他的金字塔理论提出,一旦满足了底层的需求,人们会寻求它们最深层次的需要和渴望:内在目的实际上是让人生更具价值。

一旦人猿有了食物和满足感,人猿就会寻求安全感。要拥有安全感,人猿会寻找爱和所有物。那么,亲爱的,人猿就会去寻求同等地位上的尊敬以及更高层次社会的威望。至此,人猿先生不再是丛林野人和饭桶,庄严的开始了他更高层次的生活。总会有更高的动机,但是在我们照顾好基本需求之前,我们都看不到它们。

设计问题?每个人的深层需求和潜在需求都不同。

谢天谢地,在设计我们自己的球形图时,只要认识到卓越和自我实现的需求就足够了。我们控制水平线和垂直线。我们控制媒介体验中以我们的理念对自我实现进行的定义,因此我们能够在玩家和他们的新欢之间划一条直线。他们不用离开座椅,就能迎接内心对智慧,美丽和创意的需求。

在现实中,很多人都被这种观念打击,即想成为伟人只会让你离失败更近。尽管挑战这种观念不是我们的工作,但是我们的游戏却能成为一个让深层需求结出硕果的地方。

我们能将他们的思想送进眼花缭乱的天堂,让星星围绕着他们。最好的是,一旦大多数人尝到了自我实现的好处,他们就会舍弃生理需求,安全感,爱和尊重来继续品尝我们媒介体验的滋味。

供应

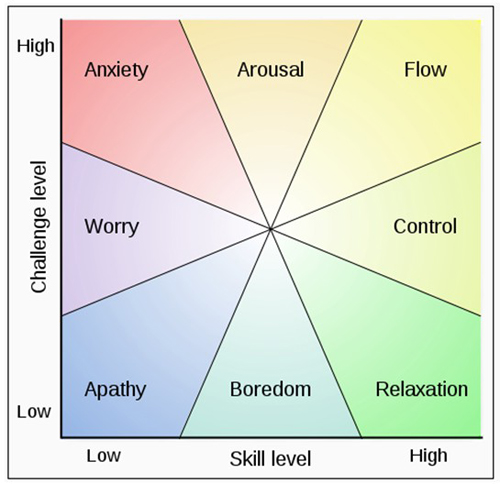

心流完美的平衡了挑战与技能。这是Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi的混合理论,它混合了我们对知觉瓶颈的认知和自我实现的人文主义理论。Csikszentmihalyi最初在管理者,运动员,知识分子,和创意者中发现了心流,当让他们描述“进入那个地带”时,就好像他们实际上超越了其职业的极限。

组织乐符,撰写脚本,或者甚至是生产线上的固定工作,都有一个点,在那个点上,创意开始自然而然的从我们的思想中倾泻或流出。

外部世界因为我们的生理机能而且断层;我们只能掌握这么多信息。视觉本身所搜集的信息要比发送至大脑的多。大脑持续的运用它接收到的少量信息来搭建实体空间的意象图,时刻接着时刻。

对于在给定的时间上工作记忆能够把握多少定理(数学的或艺术的)和策略(生理上或精神上)是有生理局限的,意味着实际的心流似乎遵循10000小时法则。即,要比普通人进行更多的练习。这是游戏之所以如此重要的原因。

设计师可以借助心流的投入,这只需要其中的一个片断。在现实中,我们喜欢让我们有完成某些深奥的事情的成就感。在这种方法中,心流状态极其强大。它们能够为玩家提供全部物有所值的生活乐趣,不带有任何的挣扎。

赖以生存

每件好的事情都有其批判性。Ian Bogost尤其对心理学应用上的赢家 – 社交游戏嗤之以鼻。Bogost对其表示担忧,认为它传播了四种倾向:框架性,强制性,可选择性,并摧毁了时间。关于框架性,他表示,社交游戏鼓励对象化,“朋友不是真正的朋友;他们只是资源。”

通常,玩家,开发者,以及人们似乎并不将其他人看作“他们是谁”,而是以“他们能为我们做什么”来看待。但是如果这种情况到处都是,跨越文化和媒介,那么为什么只有游戏行业要负这个责任呢?更为重要的是,如果它已经扎根于社会,那么人们会更为容易地了解如何给自己奖励的方式。很多社交游戏玩家没有时间学习复杂的规则 – 因此这是最不令人厌恶的,也是最有趣的。

Bogost还认为多数社交游戏强迫“Brain Hack”,这只会起到让我们持续点击的作用。然而逐步建立的点击,点击 – 正是奖赏。这些点击是设计精华的乐趣,是游戏唯一实际的目的。

关于可选性,Bogost主要批评技巧含量较少的GameVilles,游戏中通过花钱能够避免机械的点击。这只是游戏设计的另一个层面。这里我们已经赋予了挑战和技巧,显然这些挑战和技巧都消失不见了!用户只是去买他们的快乐,达到了更为有力的神经化学上的奖赏,或乐趣。每个人都是赢家。

对于摧毁时间,Bogost说,“社交游戏垂涎我们的时间,当离开它们的时候就通过义务,担忧,和错失良机来抓住我们。”他甚至对是否有一些不应该为用户添加的性能表示担忧。

然而,这种担忧只是建立在可感知的,化学的奖赏创建之上的。记住,多巴胺是化学追求,它吊起我们的胃口。成就的小把戏不是诅咒,而是乐趣的礼物。如果人们不想要(或不需要)乐趣,那么为什么Zynga还会拥有那么多用户呢?

但是那些易变的家伙们呢?他们把自己看作是浴火重生的艺术家,将我们从不需要的责任强加在我们之上。漫画作家Alan Moore(《守望者》作者),在《The Mindscape of Alan Moore》一书中这样评论传媒行业:

“他们接受了世俗的观念,认为艺术和写作只是娱乐形式。并没有将艺术和写作当作能够改变人类,改变社会的推动力。而是将它们当成简单的娱乐,只要20分钟或半个小时就能填满,然而我们在等死。艺术家的工作不是给大众他们想要的。如果大众知道他们想要什么,他们就不会是受众了,他们就是艺术家。艺术家的工作是给大众提供需求。”

错误,我们的行业不需要安乐椅批判或模糊的文字参考。大众购买产品。他们不是要花费时间找出实际上成为了下一个Jimi Hendrix或Peyton Manning的心流,我们的工作不是激发那种程度的沉浸或上瘾。我们的工作在于创造《吉他英雄》或《Madden》,尽可能给玩家最为即时和有力的一击。

如果责任不在我们的玩家,它必然在我们的股东手上。没有创意项目会在缺乏资金的情况下成功,这是公认的常理。如果我们从发行商,投资人,或股东手中拿钱,那么我们就要履行法律和道德义务,用我们的力量为他们的投资带来回报。

甚至在没有投资人的情况下,运用心理学理论仍有助于控制我们自己的目标。它帮助我们让项目进展顺利。

艺术家

好的商人显然会节约打印游戏生理拷贝的费用;也许很快我们也会合成产生体验的种子。这棵树的分支能有多长!它的成果会有多么诱人!不要提醒我统一艺术家,棘手的事情和反复无常的细枝末节!我让他进化!

随着我们社会的进步,奖赏,GPS芯片和屏幕更深入的植入到现实中了,我们会越来越好。我希望更多的学院教授和辍学生成为让我的生活更有乐趣的游戏设计师。请不要询问我的许可。我想要的奖赏是按时睡觉,对我的牙膏品牌的忠诚度,以及去玩其他人的规则。

像大多数普通人一样,我不希望去为我自己的生活承担责任。我只想要乐趣。如果你给我你所认为我应该做的,这不再是我的问题;我从惹人讨厌的担忧中解脱,世界的回报有意义。

我从游戏中获得的乐趣只是生理上的愉悦。如果你停止这日益增加的乐趣,我就一无所有了。我不能改变我人生的方向。请别让我改变。那不是你的工作。我购买产品,这个产品让我从该死的世界转移注意力。每个人都这样认为。

由于人们对奖赏行为所涉及的要素自然而然的显示好奇并进行思考,他们当然会对传媒行业对心理学的应用有所了解,尤其是游戏行业。他们会推崇你所开发的心理需求,并购买更多的游戏。

你看到了,乐趣必须是游戏的中心要素。你不是有着力量和承诺的新行业,只是旧机器上的新嵌齿。你总是这样。小团队在车库里开发游戏是谎言。某人因为热情而不是利润去开发游戏,或者为了创造新东西而承担风险也是谎言。没有少于20小时游戏时间的游戏会盈利,最新的图形引擎和大量的开发资金都是市场营销。

创意总是责任控制的练习,最重要的是,记住乐趣是心理学。心理学即乐趣。(本文为IIEEG编译,由游戏邦/gamerboom.com整理发布)

[In this thought-provoking piece, psychology researcher and author Clark takes a look at how psychology and can must be applied to game development, to produce works that engage audiences -- offering up concrete examples of the right techniques.]

Gaming’s core is fun, and psychology is fun’s touchstone. This article restricts itself to psychology’s most foundational, most immediately-applicable methods for crafting sticky, captivating experiences. From behaviorism’s methods for structuring overpowering rewards, to motivational theories on generating wants and needs, to hybrid theories like flow, it is no longer fiscally responsible for games companies to shun psychology. Let’s jump right in.

The Heart Asks Pleasure First

Pleasure first, and then, excuse from pain, shape every move that we will ever make — so say the behaviorists. It may sound callous, or reductionist, until we realize that the overwhelming majority of life’s rewards and punishments are too tiny or timeworn to remember.

Whether we know it or not, whether we like it or not, behavior is shaped by reward. Through behavioral tenets, psychologists have conditioned pigeons to play piano, play ping-pong, and to spot drowning men and women while mounted onto Coast Guard helicopters.

Operant conditioning, often associated with Edward Thorndike, then B.F. Skinner, is the study of how any behavior can be strengthened through reward.

There are two fundamental ways to strengthen behavior through reward: bring pleasure, or excuse pain. Positive reinforcement, and negative reinforcement, respectively. There’s also punishment, which introduces sharp consequences but does not necessarily remove what first reinforced a behavior.

Not all rewards are created equal. Primary reinforcers are so named because they are the most automatically powerful, and rely on the innate; some examples would be sleep, visual surprises, or sex.

Let’s talk about sex. Whether or not a player realizes, a physically attractive character, when on screen, will serve as an innate positive reinforcer. On the flipside, allowing the player to remove visually aversive characters or imagery is an innately rewarding negative reinforcer. If we care about giving players pleasure, and fun, then we will first work to maximize primary reinforcers.

Though it takes little work to reward ourselves with primary reinforcers, we often associate them with other stimuli. Classical conditioning, the precursor to Skinner’s work, would call innate pleasures the unconditioned stimulus because they’re automatic. No association necessary.

For me, a powerful association comes from that one scene from The Hangover (at the tail of this trailer), when, to the famous movement of Phil Collins’ In the Air Tonight, Mike Tyson has his moment with Zach Galifianakis. If you’re not expecting it (and for some of us doubly so once we do expect it), this is a novel visual stimulus which provokes an innate physical response.

In the Air Tonight is now for me a conditioned stimulus. I wait the whole song, building up to that movement, which due to the visual association acts as a conditioned response with a very particular reward. I grin. In classical conditioning the level of reward is typically dictated by the timing (the above scene is timed to match the song), intensity of the innate stimuli (Tyson is an intense guy – but some folks might not even notice this scene), and the frequency with which the two stimuli are paired (How many times have you seen The Hangover?)

After enough pairings, many rewards become secondary reinforcers. Money, barter objects, praise, achievements, though there are few limits to what can become attractive by association, we’ll want to first take advantage of culturally popular reinforcers. Money is great for developing games in any Western market, because we can literally drown players with money.

Though not every monster is fun to kill, or working for the equipment upgrade delivery service, each may carry the universal symbol for reward. It’s as Madonna once said: “the boy with the cold hard cash is always Mr. Right.” Though some designs will be too abstract for some secondary reinforcers, working with the grain of cultural assumptions helps to make reinforcement obvious and powerful. It makes the game fun.

But a fun game won’t just throw money, goods, or innate rewards at players; it will deliver those on a weighted and considered schedule. Foundationally, behaviorism offers us five foundational ingredients for a healthy and balanced reward schedule. Firstly, continuous reinforcement operates just as it sounds. We reinforce a player every single time they perform the behaviors that we’d like to see. We may even reinforce behaviors that get incrementally closer to what we’d like to see, what behaviorists call shaping.

A great example for both continuous reinforcement and shaping is level one in World of Warcraft, regardless of race or class selected. Learn to walk properly, kill efficiently, use skills, loot, sell, etc., and there’s no dearth of praise, experience, and cash value. Yet, continuous reinforcement is the first to wear off, because players immediately notice once you’ve staunched the flow of reward.

So we also distribute rewards in ratios and intervals. Sometimes these are fixed ratios, or fixed intervals, rewarding only after a set number of correct responses, or rewarding after a set amount of time, respectively. We can also use variable ratios, or variable intervals, rewards that come after roundabouts a number of correct responses, or roundabouts a certain amount of time, respectively. Along with continuous reinforcement, these first five are the most common of the simple schedules.

Variable ratio is widely noted for its effectiveness and consistency. Note that such charts vary where FR and FI are concerned. Some paint FR as inciting more responses than portrayed, some paint FI as inciting fewer than portrayed. (CC: Public Domain)

Most of us have probably played through compound reward schedules (though perhaps not noticed). Say you need 100x ghoul extremities (it’s for a quest, okay?) At first you’d find extremities on one of every three ghoul corpses. Before long, however, you’d only find extremities once every two minutes, and then only on one of about every five ghouls, and then (zounds!) on every damn ghoul you’d marauded, but that didn’t last long.

Finally, once you had about ninety-five helpings of ghoul extremities, you could only seem to find one every, say, three minutes or so. Noticing this is not purely paranoia. Using simple schedules in tandem, as with the example above, is common.

If a quest-giver actually provides us some indication of the reward conditions, for instance, “just kill six ghouls,” then, “gooooood, now kill one every minute for fifteen minutes, that shall work quite nicely,” and so on, until there’s an extremity-themed reward at the tail end, behaviorism also calls this a chain. If you’re looking to go further with compound schedules, Wikipedia (as usual) is a great place to start, though (as usual) is not always scholarly.

As with game design, behaviorism encourages seeding concurrent reward schedules. They let our brain pick and choose the best way to reward itself. The key to generating fun in the brain of the player is to cater to them. They should always have options for how they want to stimulate themselves. Don’t bother them with aversive situations. We already know about the world we’re escaping from.

It’s as the great Dr. Frank-N-Furter once said, “Give yourself over to absolute pleasure.”

Though do so with savvy. It may, for instance, help pleasurability to take short breaks now and again, as pointed out by this short Gamasutra piece on hedonic adaptation. Well-structured rewards may make it hard for us to do this ourselves, as our chief neurochemical for motivation, dopamine, has been shown to have less to do with pleasure than with appetite, or “seeking.”

Our brain changes itself structurally, over time, in a process called plasticity. Though we may feel the delightful spritz of dopamine the first few times we encounter a new stimulus, before long we rewire to feel the need of these once-novel stimuli. Rewards then begin to trigger the same motivational neurocircuitry as food, sex, stress, and so forth. Games, therefore, must further their understanding of this neurocircuitry, as well as behaviorism, should they desire to keep up the pace.

The Definition of Love

Now let’s look at the player’s deep-seated needs, desires, and loves. Rather than exploring behavioral reward, motivational theories ask about our optimal levels of stimulation, as well as what drives us to seek out certain experiences. Freud made the first list of instinctual motivations, unsurprisingly comprised of aggressive and sexual impulses.

William James’ list was longer, including such instincts as emulation (or rivalry), pugnacity, (anger and resentment), sympathy, hunting, (novelty of) strange men or animals, (fear of) black things or dark places, kleptomania, shyness, jealousy, cleanliness, and so on. The problem with these instincts is that after many years and many theorists, the list is unmanageably bloated.

Much like Behaviorists, motivational theorists begin to parse these instincts by distinguishing between primary (innate) and secondary (learned) drives. Drive theory suggests that all motivation is a matter of seeking homeostasis.

Biologically we maintain blood sugar and body temperature, but once everything there is in order we also seem to have intrinsic needs to test novel stimuli and to seek out a certain level of arousal. We may extol simple motivations, for instance “the open steppe, fleet horse, falcons at your wrist, and the wind in your hair.”

But perhaps Freud was closer to the truth. Sex and action hold an inherent, biologic “push,” that may have some feeling more intrinsically good when able to, “Crush your enemies, see them driven before you, and to hear the lamentation of their women.”

Sensation seekers will go after overly high levels of thrill and danger, though even these individuals will vary in the exact level that they want.

Add to that push the considerable “pull” to incentives, social needs, and self-actualization. We don’t come out of the womb with some insatiable need to tweet every five minutes through our 3G Droid app, though past rewards and good associations can teach us that doing so makes our brains happy.

Our brains will help us to change our beliefs and values when they’re at odds with that happiness. This state of tension is called cognitive dissonance, and statements like, “Smoking isn’t so bad,” or, “Cancer doesn’t run in my family,” are examples of our natural human reactions to it. As are, “Gaming through my anniversary wasn’t a big deal,” or, “There were already problems in my marriage.” Thankfully these reactions to cognitive dissonance eliminate aversive discomfort naturally, helping us stay on track, and allowing the human body to keep seeking fun.

Abraham Maslow forwarded the famous Theory of Human Motivation, whose pyramid suggests that once lower-order needs have been satisfied, people seek out their most deep-seated wants and desires: the inner goals which truly make life worth living.

Once Tarzan have food and gratification, Tarzan seek safety. Having that, Tarzan may just look for love and belonging. Then, dear chap, Tarzan might chance to find out the respect of his peers and the prestige of higher society. Whereupon Sir Tarzan, bushman and scallywag no longer, augustly inaugurates his more empyrean avocations. There are always higher motivations, but we often can’t see them until we’ve taken care of basics.

The design problem? Everyone’s deep-seated needs and potentials are different.

Thankfully, when designing our own planispheres, just acknowledging the desire for transcendence or self actualization is enough. We control the horizontal and the vertical. We control what it means to self-actualize in our slice of the media experience, so can draw a straight line between players and their new loves. They can greet deep inner desires for wisdom, beauty, and creativity without ever having to leave their couch.

In reality, many people are stymied by the belief that attempting greatness only sets you closer to failure. Though it’s not our place to challenge those kinds of beliefs, our games can be the one place that deep desire comes to fruition.

We can send their minds to the giddy heavens, conjoin them with the stars. Best of all, once most folks get a taste for self-actualization, they’ll sacrifice physiological, safety, love, and esteem needs in order to keep tasting the sweet magnanimity of our media experience.

Provide, Provide

Flow is that perfect balance between challenge and skill. It’s Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi’s hybrid theory, which mixes our knowledge of perceptual bottlenecks with humanistic theories of self-actualization. Csikszentmihalyi originally found flow among executives, athletes, intellectuals and creatives, when they sought to describe the “getting into the zone,” that happened as they truly surpassed the mundanities of their craft.

Composing melodies, writing a screenplay, or even perfecting a set job on a factory line, there’s a point at which creative generation begins to pour, or flow, naturally from our minds.

The outside world is tuned out due to our physiology; we can only process so much information. Vision alone collects vastly more information than what is sent to the brain. The brain is constantly using what little information it receives to construct mental maps of physical space, moment-to-moment.

There’s a physical limit to how many theorems, mathematical or artistic, and stratagem, physical or mental, can be held in working memory at any given time, meaning that reality’s flow seems to follow the 10,000 hours rule. That is, it takes more practice than any typical person can manage. This is why games are so important.

Designers can tap flow’s engagement, while demanding only a fraction of the dedication. In reality, we favor the challenges that make us feel we’re accomplishing something profound. In this way flow states are immensely powerful. They can provide gamers all the joy of a life worth living, without any of the struggle.

The People Will Live On

As with every good thing, there are critics. Ian Bogost is particularly unimpressed with one champion of psychology’s deployment: social games. Bogost worries that they forward four trends: enframing, compulsion, optionalism, and destroyed time. By enframing he means that social games encourage objectification, where “friends aren’t really friends; they are mere resources.”

More and more often, players, developers, and people generally seem to see other people not as who they are, but as what they can do for us. But if it is happening everywhere, across cultures and mediums, then why is our industry the only one responsible? More importantly, if it’s already entrenched in society, then people are going to have an easier time understanding how to reward themselves. Many social gamers don’t have the time to learn more complex rules – so this is the least aversive, and the most fun.

Bogost also calls much of social gaming compulsive ‘brain hacks,’ which only serve to keep us clicking. Yet the buildup to the click, and the click, are rewards. These clicks are the fun that design distills, and the only real purpose of a game.

By optionalism Bogost is primarily critiquing the skill-less GameVilles, where rote clicking can be avoided by spending money. This is just another height for game design. Here we’ve painted the appearance of challenge and skill where clearly there is none! Users who pay simply buy their own happiness, achieving more powerful neurochemical rewards, or fun. Everybody wins.

Of destroyed time, Bogost says, “Social games so covet our time that they abuse us while we are away from them, through obligation, worry, and dread over missed opportunities.” Such that even he worries if there’s some feature he oughtn’t to add for users.

And yet, this worry only adds to the buildup of tangible, chemical rewards. Remember that dopamine is a chemical seeking, it whets our appetite. These little ticks of achievement are no curse, but rather the gift of fun. If people didn’t want (or need) fun, then why does Zynga have so many users? Riddle me that, Bogost-man!

But what about those fickle folk who, considering themselves fireborn artistes, foist responsibilities we never asked for? Comics author Alan Moore (best known for Watchmen), in The Mindscape of Alan Moore, says of the media industry:

“They have accepted the prevailing belief that art and writing are merely forms of entertainment. They’re not seen as transformative forces that can change a human being, that can change a society. They are seen as simple entertainment things with which we can fill twenty minutes, half an hour, while we’re waiting to die. It is not the job of artists to give the audience what the audience wants. If the audience knew what they needed, then they wouldn’t be the audience – they would be the artists. It is the job of the artists to give the audience what they need.”

Wrong. Our industry doesn’t need easychair critics or obscure literary references. The audience pays for a product. They aren’t paying to spend a decade finding the flow of actually being the next Jimi Hendrix, or Peyton Manning, and it’s not our job to inspire that level of dedication or drug use. It’s our job to create Guitar Hero, or Madden, and to give players the most immediate and powerful kick possible.

And if the responsibility isn’t to our players, it surely is to our stockholders. It is a truism that without money, no creative project would ever lift more than two inches from the muddy ground. If we take money from publishers, from investors, or from shareholders, then we then have a legal and moral obligation to do everything in our power to give them a return on that investment.

Even where there are no investors, using psychology helps us to stay in control of our own destinies. It helps us to get it all right.

An Artist

A good businessman would obviously weed out costs related to printing physical copies of a game; perhaps soon we could also synthesize the seed which produces experience. And how long the branches of such a tree! How tempting its fruit! Do not remind me the trifles of consoling the artist, tender and fickle! I have here his evolution!

As our society moves forward, and rewards and GPS chips and screens are further integrated into reality, the better off we’ll be. I want more college professors and college dropout turned game designers making my life more fun. Please do not ask for my permission. I want to be rewarded for going to sleep on time, for being brand-loyal with my toothpaste, and for playing by another person’s rules.

Like most reasonable human beings, I do not want to take responsibility for my own life. I want only fun. If you reward me for living how you think I ought to, it is no longer my problem; I am saved from aversive worry, and the world’s rewards make sense.

The fun that I get from gaming is the only physically pleasurable outlet I have left. If you stop this ever-increasing cascade of fun, then I will have nothing. I cannot change that aspect of my life. Please do not ask me to. That is not your job. I pay you for a product, and that product is a distraction from a world of shit. Everybody in the world feels this way.

Since people are naturally inquisitive and thoughtful where extremely rewarding behaviors are concerned, they will of course become savvy to how psychology is being employed by the media industry generally, and the games industry specifically. Where this happens they will laud you for creating this physical need, and buy even more of your games.

So you see, fun must be the central element to games. You are not a new industry with power and promise, you are just a new cog in an old machine. You were always this way. Myths of small groups making games in garages are lies. It is also a lie that anyone has ever worked on a game for passion rather than profit, or taken a personal risk in order to create something new. No game has ever been profitable with less than 20 hours of gameplay, the latest graphics engine, or millions of dollars in marketing.

Creativity is always an exercise in liability control. Most of all, remember that fun is psychology. Psychology is fun.(source:gamasutra)

闽公网安备35020302001549号

闽公网安备35020302001549号