关于印度游戏市场下载,用户体验和消费意愿的分析

本文原作者:Matthew Handrahan 译者:ciel chen

对印度游戏行业,即使最粗略的分析都能知道其潜力与现实之间存在的鸿沟。

印度的希望是可以被迅速而且有力地被实现的,仅仅通过他们庞大的12.5亿人口就行。阻碍的问题是:尽管有一半的人口拥有了手机,会进行APP内购买行为的受众对于游戏开发者来说是复杂并有关联性的,这需要多种的解决方案,也因此会花费他们非常大量的时间。

Nazara Technologies公司打赌5年能看到一个成熟的印度游戏市场。Moonfrog Labs则认为是10年。

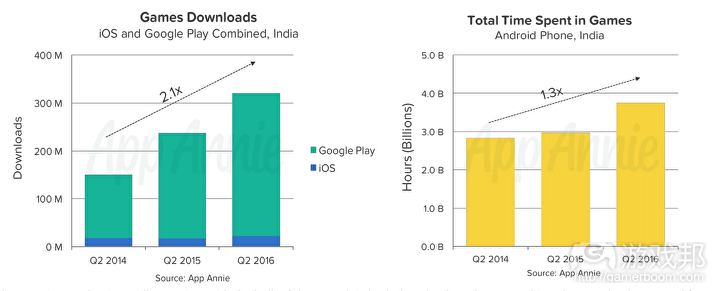

对于Nasscom Gaming Forum的董事长兼Dhruva Interactive的创始人(于去年被Starbreeze收购)——Rajesh Rao来说,至少有机会看到了印度游戏行业发展的基石。根据被特别委托的App Annie报道(于去年在Nasscom GDC正式公布),印度首次成为iOS和Google Play2016年第二季度游戏下载量前五名之一的国家,在一年的时间越升了两名仅次于俄国、巴西、中国和美国之后位居第四。

看到2016年累积的16亿下载量,Rao相信印度市场潜力的最大问题之一已经有了答案。

“证据就在下载量的增长中,”在我们的Nasscom GDC会面中他这样说。“十六亿的下载量出现了。这真实发生了。印度现在是前五名国家之一了,我们还会攀得更高。根据CAGR(年复合增长率)显示,我们可以进入前三”

“是否越来越多的人在玩游戏已经不是一个争论点了。现在是要看有多少人会为游戏付费。这个才是要讨论的。”

App Annie的数据,其持续增长的数字表明印度人会继续玩下去。十六亿的积累下载量预计在2020年会达到53亿;在同样地时间表里,Statista预测印度的手机用户数量将会从2.92亿增加到4.44亿。这是个庞大的数字,也意味着一个庞大而有价值的市场,但是这也是造成印度潜在能力与现实表现之间一道鸿沟越发明显的要点所在。同一季度,印度在iOS加安卓平台游戏下载量排世界第五名,App Annie的数据表示总收入只有1600万美元。两年前,在2014年第四季度里,印度游戏总收入为900万美元。

根据App Annie所示,在收入增长方面印度游戏正处在快速改变的风头浪尖。87%的CAGR会推动印度手游市场,使其年收入在2020年达到11亿;市场价值大幅进步的今天,这样的数字会抓住很多国际公司的眼球。当我对Rao提到App Annie这个项目的时候,他的回答相当慎重。

“当我们看到这个结果的时候,我们觉得……这似乎是一个相当积极的预测。但让人们为游戏买单会是一个心理层面的转变。这个改变的决定权在他们手上。你可以创造出点东西加速这个改变,但是你无法逼迫玩家做出改变。”Rao这样说。

为了实现这个改变,出现了各种“赋能品”被研发应用来缩短这个转变的过渡期:有Google和Facebook都积极推行的——更高速、更实惠、无处不在的无线网络,有移动钱包、运营商扣账的付费方式、以及更多的支付选择;还有,自从Google Play(目前最流行的电子商城)把最低消费从50卢比降低到了10卢比,移动App store消费门槛也降低了。

然而,Rao快速地指出对印度游戏业来说是没有“速效剂”的。他更愿意看到App store的最低消费再下降更多。比如说从5卢比降到2卢比,这会让支付变得更加可行来吸引成百上千万的人们来消费。Rao还说这个问题不仅仅跟印度的基础建设有关,更多还得追溯到印度历史的“文化”方面。 “运营商扣账的付费方式不是一个特效药,”他提到App Annie报告中提到的“赋能品”之一。 “它一定会有所成效的,但并非是唯一能支撑住我们的。”

但是文化在改变,Rao相信印度电影市场的成熟会是游戏市场未来的缩影。一张电影票的价钱“在5至25卢之间已经是非常久的事了,”但是在过去十年里电影产品的进步——让不断发展的中产阶级相信体验有更高的价值所在。 “现在你为了一场周五表演花500卢比,没人为此觉得心痛。”

电视节目也有相同效果,有一点就是,它们是属于国家的。根据Rao所说,第一个私人频道是在90年代早期引进的,全部由广告商资助。后来这些频道需要通过有线电视运营商进行订阅,可以套餐订阅或者单独订阅。“这个频道5卢比一个月,那个频道7卢比一个月,从今往后的15或者20年后,有些频道可能会标价到150卢比一个月。”

“重要的是,最终,【印度人】会为游戏内容买单。但是历史数据告诉我们,我们印度人喜欢免费,所以这还得耗些时间。”

如果Rao说的没错的话,这抛出了一个对于这个国家的开发者群体很重要的问题,他们大部分是以小团队的形式存在的,资金渠道有限,而且很难让发行商发现他们。这些因素都让iOS和安卓商店首页成为了印度游戏通向商业的最可行途径,但是这当中的收益并不足以支撑他们继续下去。

对于Rao来说,印度游戏创业环境的经验不足——这跟印度游戏业的相对年龄有不可避免的关系——让开发者们很难做出当务所需的选择。他们的选择多出于对游戏的激情,却脱离了创业的现实性和实际生存的必要性。

“我认为很多开发者都是不假思索就跳进了这个行业。印度与西方的开发者群体不同的特点在于他们很多是在大公司有工作经验的人,他们在游戏里已经投入了自己的青春,他们是有经验的。然后,他们从大公司里跳出来开始自己的事业。

Rao说印度的开发者群体很年轻,相对于那些全球各地已经发展完善的企业来说,他们的管理费用较低。“他们可以在创业道路上奔跑很长一段时间。但是,最终,如果你赚不到钱那……现实就是很多这样的年轻人会做很多反思思考他们要如何生存下去。

“独立游戏的概念、做自己的游戏、做我想做的游戏——这都是扯淡,因为这些都没法养活你。很多人就陷入了这种想法里,这种想法很好非常好,但是,钱从哪里来?”

“如果你没有一个成功的商业模式,在某种意义上来说你的创业之路已经结束了。”

Rao举了个例子,Timus就是先在印度所需要的开发者,它由Ahmed Mohammed创立于海德拉巴(印度南部一城市),从一个四人小组在六年内发展到百来人。它制造的游戏是按照一个很紧凑的时间进度在发行,涵括了各个种类游戏,稳健地发展了足够庞大的玩家受众,通过植入广告盈利。这个公司迄今为止的最大型游戏是《模拟火车2016》,但是Timuz并非仅仅靠单一的产品发展,而是主要靠投资组合的力量。”

“那家伙简直要命。就我所知他可是赚了大钱了。也就是说他看破了些东西。他明白印度现在还不是付费的时候,所以他主攻投资组合这块……好样的,再接再厉。他在做这些的时候,有一个相当图书馆那么大的内容库,装了足够多有关游戏类型和游戏风格的内容,他现在所掌握的数据会在未来帮到他。”Rao说道。

“聪明。这的确是个聪明的独立游戏开发者”

本文由游戏邦编译,译者ciel chen,转载请注明来源,或咨询游戏邦,微信zhengjintiao

“India is now a top five country, and we’ll probably climb further”

Indian people are playing, says Dhruva’s Rajesh Rao, but the road to payment might be long, and unforgiving for the country’s indie developers

Matthew Handrahan

European Deputy Editor

Wednesday 8th March 2017

Even the most cursory analysis of the Indian games business reveals the vast gulf between potential and reality.

India’s promise can be encapsulated, swiftly and powerfully, by a single, very large number: 1.25 billion, the country’s population. The problems that stand in the way of even half that number becoming a smartphone owning, in-app purchasing target audience for game developers are complex and interconnected, demanding a variety of solutions that will play out over very different timescales. Nazara Technologies sees a mature Indian games market as a five-year bet. Moonfrog Labs has suggested ten.

For Rajesh Rao, the chair of the Nasscom Gaming Forum and founder of Dhruva Interactive, which was acquired last year by Starbreeze, it is at least possible to see the founding stones on which the Indian games business will be built. According to a specially commissioned App Annie report, officially unveiled at Nasscom GDC last year, India entered the top five countries for combined iOS and Google Play game downloads for the first time in Q2 2016 – jumping two places in the space of a year to nestle behind Russia, Brazil, China and the US.

With 1.6 billion downloads accrued for the whole of 2016, Rao believes that one of the great questions over the potential of the Indian market has been answered.

“The proof is in the downloads growing,” he says when we meet at Nasscom GDC. “1.6 billion downloads has happened. That’s not notional. India is now a top five country, and we’ll probably climb further. Based on what the CAGR is showing, we could go into the top three.

“Whether people are playing is no longer a debate. Now it’s a matter of how many people will pay. That’s the debate.”

App Annie’s data indicates that Indian people will continue to play, and in ever increasing numbers. The 1.6 billion downloads amassed last year is projected to reach 5.3 billion by 2020; in that same timeframe, Statista forecasts that the number of smartphone users in India will rise from 292 million to 444 million. These are huge numbers, suggestive of a huge and valuable market, but this is the point at which the gulf between potential and reality becomes startlingly apparent. In the same quarter that India placed fifth in the world for iOS and Android game downloads, App Annie’s data shows total revenue of just $16 million. Two years before, in Q4 2014, total revenue was $9 million.

According to App Annie, that is on the cusp of rapid change. A CAGR of 87% will push the Indian mobile games market to $1.1 billion in annual revenue by 2020; a vast improvement over the value of the market today, and the kind of figure that would draw the gaze of many international companies. When I mention App Annie’s projection to Rao, though, his response is notably measured.

“When we saw that, our view was… it seemed like a fairly aggressive extrapolation,” Rao says. “Getting people to pay is a change in mindset. It has to come from themselves. You can create things that help to accelerate it, but you cannot force them.”

To that end, there are “enablers” being developed and implemented to hasten that transition: faster, cheaper and more pervasive wireless internet, which both Google and Facebook are actively pushing; mobile wallets, carrier billing, and a broader range of payment options; lower payment thresholds on the mobile app stores, after the minimum price tier on Google Play (by far the most popular store) dropped from Rs. 50 to Rs. 10 (about 15 cents).

However, Rao is quick to point out that there is no “magic bullet” for India. He would like to see a further reduction in the minimum app store price tier, for example; RS. 5 or Rs. 2, which would make payment more feasible and attractive for millions of people. Rao describes the issue of payment in terms of India’s “cultural” past rather than simply about infrastructure.

“Carrier billing is not a magic pill,” he says, referring to one of enablers mentioned in App Annie’s report. “It will definitely show results, but it’s not the only thing holding us back.”

But culture’s change, and Rao believes the maturation of the Indian film market is indicative of what lies ahead for games. The price of a cinema ticket was “between Rs. 5 and Rs. 25 for a very long time,” but an improvements to the product over the last ten years – in the form of modern theatres, and films with better production values – has convinced the growing middle-class that the experience has a higher value. “Now you could have a Friday show for 500 rupees,” Rao says. “And nobody’s blinking.”

The same effect can be seen with television, which at one point was operated by the state. According to Rao, the first private channels were introduced in the early 90s, all of them funded by advertising. Then channels were offered for subscription through cable operators, in bundles or individually. “This channel is Rs. 5 per month, that channel is Rs. 7 per month,” he continues. “Cut to now, 15 or 20 years later, some channels are priced at Rs. 150 per month.

“The point is that, eventually, [Indian people] will pay for game content. But the historical data shows that we love free, and we take a little time.”

If Rao is correct, this poses a significant problem for the country’s community of developers, most of whom are in small teams, with limited access to funding, and far from the radar of international publishers. These factors make the Indian iOS and Android storefronts the most accessible place to do business, but there isn’t much revenue to go around.

For Rao, the lack of experience within the Indian startup scene – unavoidable given the relative age of the country’s games industry – is preventing developers from making choices that the situation demands. Choices made from passion, rather than the reality of building a business and the pragmatic necessity of survival.

“I think there’s a lot of developers who just jump in without thinking,” he says. “The developer community in India, the characteristic that distinguishes it from the community in the West, is that the startups there are more often than not people who have worked in large companies; they’ve put in their years, they have experience. Then, after that, they’re stepping out into startups.”

India’s developer community is young, Rao says, with much lower overheads than in more developed industries around the world. “They can make their runway last for quite a while. But, eventually, if you aren’t making money… The reality is that a lot of these guys are going to do a lot of soul-searching at some point, about how they can really survive.

“This notion of indie, and doing my own game, making the games I like to make – all nonsense, because that doesn’t feed you. A lot of the guys got caught up in that kind of thinking, and it’s all fine and dandy, but where is the money?”

“If you don’t have a successful business model, then at some point you come to the end of your runway.”

Rao offers Timuz as an example of the kind of developer that India needs. Founded in Hyderabad by Ahmed Mohammed, Timuz has grown from 4 people to more than 100 in just six years. It produces games on a very busy release schedule, spanning multiple genres, steadily building a large enough audience to monetise through interstitial advertising. The company’s biggest game to date is Train Simulator 2016, but Timuz is thriving on the strength of a portfolio rather than any one product.

“That guy is killing it,” Rao says. “He’s making a ton of money, from what I know. That means he’s cracked something. He understood that Indians are not paying yet, so he’s building a portfolio…. Good man. More power to you. In doing so, he has a library of content in enough genres and enough styles that he now has data that can help him in his future.

“Smart. That’s a smart indie.”

GamesIndustry.biz is a media partner for Nasscom GDC. Our travel and accommodation costs were provided by the organiser.(source:games industry.biz )

闽公网安备35020302001549号

闽公网安备35020302001549号