以斯金纳原理分析社交游戏道德性及趣味性

作者:Benjamin Jackson

19世纪90年代,苏联生理学家巴甫洛夫(Ivan Pavlov)在圣彼得堡大学研究自然科学,分析狗的唾液分泌情况。巴甫洛夫发现,狗在被喂食前会分泌更多的唾液,而且仅仅看到工作人员的白色实验服就会引发唾液的分泌,即便实验员手上并没有食物。所以,他尝试在给它们提供食物时摇铃,发现随着时间的推移,狗在听到铃声后就会分泌唾液,即便没有向它提供食物也是如此。巴甫洛夫的研究结果就是所谓的“条件反射”,一级强化物(游戏邦注:能够自然触发反应的东西,比如食物或疼痛)与条件或二级强化物有关,比如实验服或铃声。

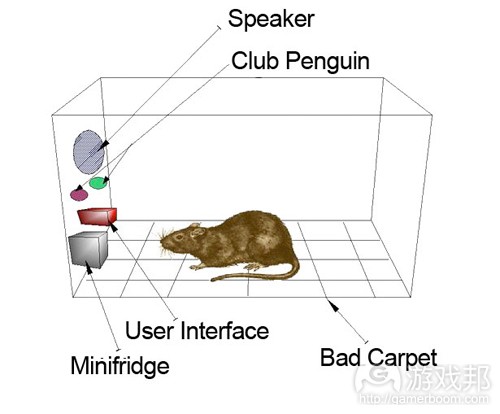

40年后,年轻的心理学家伯尔赫斯·弗雷德里克·斯金纳(Burrhus Frederic Skinner)以巴甫洛夫观察到的现象为基础构建新的理论。他建造了一个隔音且无光照的场所,在其中喂养小动物。在动物可触及的范围内放置杠杆,该杠杆可以触发一级强化物。这个被称为斯金纳盒的设备成为随后许多实验开展的工具,这些研究都获得了一定的突破,比如可卡因在单独环境与较大社区中的相对成瘾性以及探索老鼠是否拥有情感共鸣等问题。

现在,斯金纳被誉为操作性条件反射之父,这是种通过联系某些一级强化物来让对象在特定条件下对二级强化物做出反应的研究形式。斯金纳的研究不仅表明自然界中的一级强化物和二级强化物存在联系,还显示出人们还可以制作出新的强化物。

斯金纳和巴甫洛夫证明,一级强化物是很强大的刺激因素。除了性行为和睡眠外,熏肉是自然界中最强大的一级强化物之一,部分原因在于,与其他肉类相比,它拥有丰富的脂肪和蛋白质。熏肉成了人所共知的“开胃肉类”,其味道可以触发很强烈的食欲,对素食主义者也不例外。但是在现代世界中,我们对熏肉和其他高脂肪事物的本能渴望会带来严重的健康问题。

这个盒子还让我们明白了两个基本道理,其中之一的延伸已经大大超过斯金纳的研究范围。与其他动物一样,人类也会对一级强化物做出很大的反应。在我们产生满足感后一级强化物的效果会减弱,于是金钱或社会地位等二级强化物便会成为我们的需求,而这些需求不存在满足点。换句话说,我们很希望能够获得同辈的认同,而且永远都不会满足于所获得的认同。

许多人认为《FarmVille》是无害之物,他们辩解就算没有玩游戏,我们也会把数千个小时浪费在其他行为上。毫无疑问,社交游戏市场依靠虚拟货币和无限的商品成为巨大的摇钱树。当你认真研究《FarmVille》后会发现,这款游戏的所有设计显然只有一个目标:尽量让用户在这片虚拟土地上多花时间。游戏利用了我们回馈好友赠礼的本能,让我们不断请求好友回到游戏中。精心设置的作物成熟时间强迫玩家每天都要定期回去查看他们的农场。其他游戏采用的又是什么技术呢?

道德性

撇开道德相对主义,假设我们能够清晰地确定“坏”的概念,我认为确实会存在“坏”游戏。在《道德形成上学基础》(Groundwork of the Metaphysics of Morals)一书中,德国哲学家伊曼努尔·康德(Immanuel Kant)尝试以“绝对命令”,即一套能够衡量行为道德性的规则对此进行定义。但是,无论我们选择如何评估游戏的道德性,必然会有些特征会将其推向“邪恶”的范围。

不道德游戏的主要特征是操纵、误导或同时兼有两者。从用户体验角度来看,这些游戏呈现出阴暗模式,比如那些引发用户做与其意志相反的设计元素。阴暗模式往往用来使成功指标(游戏邦注:比如注册邮箱、激活或升级数量等)达到最大化。

比如,《FarmVille》、《Tap Fish》和《Club Penguin》利用深层次的心理冲动来从用户处赚取金钱。通过呈现进度条,他们利用玩家更快完成的欲望,鼓励用户付费升级。游戏中的随机时间奖励像赌博机那样吸引玩家回到游戏中,即便这种行为不会让玩家获得多少好处。他们通过让玩家不断向好友提出要求来进行病毒式扩散。

这种趋势并不只在社交游戏领域中出现,还包括《美国陆军》等许多战斗游戏,这款游戏的制作由美国军方赞助,用来作为招募士兵的辅助工具。有些品牌产品也发布了Facebook游戏,比如《Cheez-It’s Swap-It!》,他们将此作为出售更多产品的工具。这些技术可以用在任意类型的游戏中和任何背景下。

当然,并非所有游戏都能够被清楚地划归善或恶。“好”游戏没有要求玩家进行批判性思考和解决问题,但是仍然会令人感到愉快。《俄罗斯方块》是款复杂和内容丰富的游戏,其吸引力与1988年首次面世时相比丝毫没有减弱,但许多人辩解称,游戏缺乏解决问题的挑战或丰富的故事情节,而这些正是《Sword & Sworcery》和《塞尔达传说》等冒险游戏充满吸引力的因素。不同的人可以看到游戏玩法不同层面的意义,这才是让玩家和游戏设计师对游戏充满兴趣的原因。

困难趣味

横向卷轴跳跃游戏《屋顶狂奔》是最畅销的独立iOS游戏之一。游戏内容是一个小人在虚拟城市的屋顶上奔跑。玩家点击屏幕让小人跳跃,小人的奔跑速度会逐渐增加。《屋顶狂奔》并没有终点,只有无尽的奔跑:目前最长的奔跑记录是,玩家花了8分16秒时间穿过22公里的倒塌建筑物、掉落的障碍物和妨碍小人奔跑的窗口。

在2011年10月的IndieCade上,《屋顶狂奔》制作者Adam Saltsman讨论了“持续时间直至死亡”的观点。我们所有人在地球上生存的时间都是有限的,无论任何时候,当我们将时间花在某个行为上,就无法将其花在另一个行为上。这意味着,我们花在游戏上的时间也是投入的成本,这项成本比我们花在游戏上的金钱还要多。如果在这段时间内能够感受到乐趣,那么这样的游戏才值得我们投入时间。

不同的人会以不同的方法来创造价值,但是最直接的是让玩家产生参与感直到他们精通游戏。2011年西雅图Casual Connect举办的讨论会上,游戏设计师兼顾问Nicole Lazzaro描述了两种类型的趣味性:简单趣味和困难趣味。如果游戏向玩家呈现的挑战没有超过“简单趣味”点,那么他们永远也不会精通游戏,这也会使他们失去玩游戏的兴趣。

Zynga纽约工作室总经理Demetri Detsaridis也参加了此次讨论会。Zynga对《FarmVille》及其同类游戏中“真正的趣味性”有着自己的看法,这种看法与公司的商业利益相符。他对公司如何利用“简单”和“困难”趣味的说法是:

我们在开发游戏时脑中并不一定有这样的框架,在我昨天看这场讨论会的主题时,我在想:Zynga的大量开发工作都是在这种‘人类’趣味和‘简单’趣味的循环间完成的。这两者之间并没有清晰的界限,存在许多重叠的部分。我觉得许多社交游戏已经做到了将‘人类’趣味和‘简单’趣味融合起来,至少3/4的游戏已经实现。所以你会看到困难趣味出现在令人惊讶的地方,比如考虑自己的社交圈范围,以及你在现实生活中如何向好友发送请求。这些都是社交游戏的组成部分,而且设计师明白这一点,所以几乎所有‘困难’趣味都是以人类和简单趣味为中心。

Detsardis同意了他的看法,本次讨论会的主持人Rob Tercek总结道:

游戏本身并不是动作发生的地方,其策略元素存在于:你要何时利用社交圈?你要何时向好友发送信息?你是否频繁使用这些功能?

用更容易理解的话来说,Detsaridis认为玩Zynga游戏最具吸引力的部分在于决定何时以及如何利用消息来提醒好友玩Zynga游戏。

创造困难趣味并不是项容易的工作,它要求设计师深入思考玩家体验,而不是只使用简单的技巧来推动参与度。《FarmVille》、《Tap Fish》和《Club Penguin》都采用了类似斯金纳的技术来说服玩家投入更多的时间和金钱。但是,创造参与度的方式还有很多,作为游戏开发者和消费者,我们有义务要求这种娱乐方式呈现更有诚意的趣味性。

游戏邦注:本文发稿于2012年1月24日,所涉时间、事件和数据均以此为准。(本文为游戏邦/gamerboom.com编译,拒绝任何不保留版权的转载,如需转载请联系:游戏邦)

The Zynga Abyss

Benjamin Jackson

In the 1890s, while studying natural sciences at the University of Saint Petersburg, a Russian mathematician named Ivan Pavlov was analyzing dogs’ saliva output over time. Pavlov noticed that dogs tended to salivate more before eating and that merely the sight of a white lab coat would induce salivation — even if no food was on the way. So he tried ringing a bell before presenting them with food, and found that over time, the dogs would salivate even if a bell was rung with no food presented. Pavlov’s research defined classical conditioning, in which a primary reinforcer (one which naturally elicits a response, e.g. food or pain) is associated with a conditioned or secondary reinforcer, such as the lab coat or bell.

Forty years later, Burrhus Frederic Skinner built upon Pavlov’s observations as a young psychologist in graduate school. He constructed a soundproof, lightproof chamber that housed a small animal; a lever was placed within the animal’s reach, which triggered a primary reinforcer. Called the Skinner box, the device opened up many possibilities for experimentation, leading to breakthroughs in later research: from the relative addictiveness of cocaine in isolation versus in a larger community, to the question of whether rats have empathy.

Skinner is now credited as the father of operant conditioning: a form of learning where a subject is conditioned to respond to a secondary reinforcer through association with some form of primary reinforcement. Not only did Skinner’s work show that associations between primary and secondary reinforcers appear in nature, it also demonstrated that new reinforcers can be manufactured.

Skinner and Pavlov proved that primary reinforcers are extremely powerful motivators. After sex and sleep, bacon is one of nature’s most powerful primary reinforcers, partly due to its high fat and protein content in comparison to other meats. Bacon has become known as the “gateway meat”: the smell triggers intense cravings, even in vegetarians. But in our modern world, our instinctual craving for bacon and other fatty foods can cause significant health problems.

The box also taught us two fundamental lessons, one of which had ramifications that extended far beyond Skinner’s experiments. Humans are hardwired to respond to primary reinforcers, just like any other animals. And while primary reinforcers have a diminishing effect once we’re satiated, secondary reinforcers, like money or social status, exist outside our biological needs, and these never hit a satiation point. In other words, we are hardwired to seek approval from our peers, and we can never get enough of it.

Many people defend FarmVille as a harmless distraction, arguing that the thousands of hours spent playing the game would still have been wasted on other activities. But there’s no question that the social game market, with its virtual currencies and unlimited stock of goods, is a huge cash cow. And it’s also clear, when you look more closely at FarmVille, that it was engineered with one goal in mind: to coerce users into tending their virtual plots of land for as long as possible. Using our natural tendency to reciprocate gratitude from our peers, we end up pestering our friends to keep returning. And cleverly-timed crop cycles force players to return to their farms at all times of day. But what about the techniques employed in other games?

Black, White, and 254 Shades of Gray

Moral relativism aside, I think “bad” games exist — provided we define “bad” in unambiguous terms. In Groundwork of the Metaphysics of Morals, Immanuel Kant tried to specifically define this with the Categorical Imperative: a set of rules that could gauge an action’s morality. But regardless of how we choose to evaluate a game’s morality, there are certain traits which can push it closer to the “evil” side of the spectrum.

The primary characteristic of unethical games is that they are manipulative, misleading, or both. From a user-experience standpoint, these games display dark patterns, which I define as common design decisions that trick users into doing something against their will. Dark patterns are usually employed to maximize some metric of success, such as email signups, checkouts, or upgrades; they generally test well when they’re released to users.

For example, FarmVille, Tap Fish, and Club Penguin play on deep-rooted psychological impulses to make money from their audiences. They take advantage of gamers’ completion urge by prominently displaying progress bars that encourage leveling up. They randomly time rewards, much like slot machines time payouts to keep players coming back, even when their net gain is negative. And they spread virally by compelling players to constantly post requests to their friends’ walls.

This trend is not just limited to social games, though: many combat games, like America’s Army, are funded by the U.S. military and serve as thinly-veiled recruitment tools. Some brands have launched Facebook games like Cheez-It’s Swap-It!, and they serve as tools to sell more products. These techniques can be used in any sort of game, in any context.

Of course, not all games fall neatly into a clear division between good and evil. “Good” games can ask little in the way of critical thinking and problem solving, but still be fulfilling. Tetris is a complex, enriching game that is just as addictive today as when it debuted in 1988; and yet many would argue that it lacks the problem solving challenges or rich plots that make adventure games like Sword & Sworcery and The Legend of Zelda so compelling. Different people find meaning and fulfillment in different aspects of gameplay; that’s what makes gaming so fun for players and game designers.

Hard Fun

One of the best-selling independent iOS games is a side-scrolling jumper called Canabalt. It consists of a tiny man running over the rooftops of a dystopian cityscape. Players tap to jump, and the gameplay speeds up over time. There is no end to Canabalt, only longer runs: the longest run yet recorded, at 8 minutes and 16 seconds, takes the player through more than 22 kilometers of crumbling buildings, falling obstacles, and inconveniently placed windows.

At IndieCade in October 2011, Adam Saltsman, Canabalt’s creator, discussed the notion of “time until death.” All of us have a finite amount of time on earth, and any time we spend on a particular activity is time that we can’t spend doing something else. This means that the time we spend gaming represents most of a game’s cost of ownership, far more than any money that we spend. If that time is enjoyable (or rather, if its benefits outweigh its costs), then the game was worth our time.

Value is created in different ways for different people, but the most immediate is through generating engagement until players achieve mastery. In a panel held at Seattle’s Casual Connect in 2011, game designer and consultant Nicole Lazzaro described two types of fun: easy fun and hard fun. Games that don’t challenge players beyond a certain point — “easy fun” — will never allow them to achieve mastery, which could deprive them of a highly rewarding part of playing.

The panel also included Demetri Detsaridis, the general manager of Zynga’s New York office. Zynga has its own ideas of what constitutes the “real fun” in FarmVille and similar games, which align neatly with the company’s business interests. His answer of how they approach “easy” vs. “hard” fun was telling:

You know, while we don’t necessarily have this framework in particular in mind… you know, while I was looking at this chart yesterday, while we were talking, I was thinking “Well, Zynga does a lot, if not most, of its development work in this kind of infinity symbol loop here between ‘people’ fun and ‘easy’ fun… there’s sort of an overlap here that isn’t maybe entirely clear on the chart, but a lot of… I think a lot of social games kind of are really quite close to the top, you know three-quarters of this, that the ‘people’ fun and the ‘easy’ fun are really sort of mushed together, and that where you see the hard fun coming in is in perhaps surprising places, like thinking about your social graph and how you, in real life, are managing that – well, am I sending, you know, friend requests to these, these people? Is that – you know, so that’s actually part of the game, and designers know that, so that sort of is an interesting almost meta-game layer of almost ‘hard’ fun on top of what otherwise might seem in this structure to be really people- and easy-centric.

Detsardis nodded in approval as Rob Tercek, the panel’s moderator, summed it up:

The games themselves aren’t where the action happens; the strategy component is: when do you reach out into your social graph? When are you going to spam that list? How frequently are you gonna do that?

I’ll reiterate this in plainer language, just in case the quote wasn’t clear: Detsaridis said that one of the most compelling parts of playing Zynga’s games is deciding when and how to spam your friends with reminders to play Zynga’s games.

Creating hard fun isn’t an easy task. It requires thinking deeply about the gamer’s experience, not just using cheap tricks to drive engagement. FarmVille, Tap Fish, and Club Penguin all employ Skinner-like techniques to persuade people to spend more time and money. But there are plenty of honest ways to create real engagement, and it’s our responsibility as creators and consumers of games to demand more honest and fulfilling fun from our entertainment. (Source: The Atlantic)

闽公网安备35020302001549号

闽公网安备35020302001549号