阐述故事元素在战略游戏设计中的重要性

作者:Joe Martin

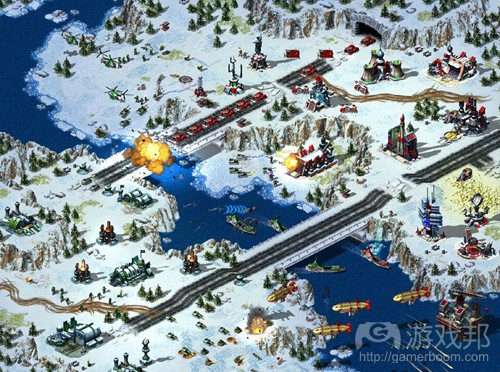

战略游戏

自从《半条命》首次向大众表明,电脑游戏可运用高超的手法处理故事元素,无需令其沦为《龙与地下城》式冒险游戏的冗长故事内容之后,“故事”开始成为游戏领域的一个热词。而之后《半条命2》则更向前一步,并使“物理效果”成了发行商关注的另一热词。

从那时候起,似乎所有类型和大小的游戏都试图将史诗般的故事和出众的角色作为卖点,Gabe Newell和Co.则让Take Two、EA等发行商开始认识到“叙述”这个新词不容忽视的重要性。

但问题是,并非所有的游戏都兑现了这种承诺,也并非任何类型的游戏都是强大的叙事载体。有些类型的游戏擅长说故事,有些则不然——这也是我们之所以无法看到拥有出众情节的《Breakout》克隆游戏的原因所在。

我们将通过本文探讨即时战略游戏(以下简称RTS)的故事元素及其未来演化趋势等内容,并引用《冲突世界》首席设计师Magnus Jensen的观点进行阐述。

《冲突世界》重塑了许多RTS故事的规则和内容,因此是这个话题的极佳案例。在多数此类游戏还在用头部特写或者在各个任务间使用FMV(全动态影像)叙述故事内容时,《冲突世界》已在使用多种手法吸引玩家。

RTS游戏究竟是怎样炼成的?

RTS是史上最易辨别的游戏类型,Westwood Studios推出了世人公认的现代战略游戏开山之作《沙丘2》,该工作室后来开发的《命令与征服》系列也成为现代游戏的鼻祖之一。开发于1992年的《沙丘2》是RTS/冒险游戏《沙丘》的继作,但所涉及的Frank Herbert(美国作家,原《沙丘》系列科幻小说作者)小说内容并不多。

我是《沙丘》小说及其原游戏版本的忠实粉丝,而《沙丘2》也是我在Amiga A500+平台上玩过的首批游戏之一,因此对该游戏较为了解。

《沙丘》系列包含了RTS游戏所需的大量重要元素,Westwood当时也应该找不到一部比它更适合开发成游戏的小说——该小说提供了玩家所需搜集的资源(Spice Melange),明确定义了玩家需打败的敌人,以及制造大量冲突的史诗情节。小说甚至还提到了Kanly这种主导科幻环境战斗情形的一系列规则。

但自从《沙丘》问世之后,人们却很难再向RTS游戏中深度植入故事情节。开发者们很难找到此类现成的故事框架(尽管他们已经更清楚哪些内容可行,自己需要什么元素),之后问世的游戏也证实了这种情况。虽然以游戏的标准来看,《命令与征服》的故事也令人印象深刻,但却无法与《沙丘》小说的精密性相提并论。不过它的玩法却比《沙丘2》更胜一筹。

如果我们排除了那些不甚重要的游戏以及《沙丘2》克隆版本,我们就会发现这一领域已经从强大的玩法结合出众的故事,转向丰富的游戏机制给较少的故事元素这种趋势。但这一点很重要吗?虽然故事元素更少了,但游戏玩法却显著提升,对军队微观管理元素的减少,也开创了RTS游戏的新局面。随着RTS在PC平台的繁荣发展,《Stonkers》等含有模糊RTS特点的早期游戏也被人们抛至脑后。

那么,故事元素对RTS游戏而言究竟有多重要?如果《命令与征服》能够像《沙丘》一样成功平衡故事和玩法,那么其他设计师又该如何在自己的游戏中把握这种平衡?这是否就能证明,玩法在RTS这类游戏的重要性甚于故事情节?

Magnus Jensen的看法如下:

“我原先认为游戏玩法与故事元素的关系,在RTS与在其他任何类型的游戏中并无不同。有许多行业讨论及GDC演讲也常将RTS游戏与其他类型游戏中的这一话题等量齐观。”

“但对《冲突世界》来说,故事元素极为重要,单人模式是一种极为线性和富有情感的体验。如果剥离了单人模式中的故事元素,它与其他多RTS游戏相比就会显得特别肤浅。”

我认为这也许和故事的叙述方式有关。设计师究竟要怎样向玩家传达故事和目标?任务简报也许是一个符合逻辑的方法,而且比起其他类型的游戏,它更适用于RTS游戏。但《毁灭公爵3D》如果每遇到一个敌人前就给你来段5分钟简报,那这样的游戏未免也太无趣了!

RTS的重心正从讲述故事向游戏玩法转移,但在游戏事件中引入目标和叙述内容却能为游戏增加一种戏剧性和紧张感——看看《命令与征服3:泰伯利亚之战》多少次弹出女演员Jennifer Morrison的头像就知道了。

Magnus对此表示:

“过场动画是一种开发成本极高的方法,所以开发者有时候也只用配音或头部特定叙述简报内容。极少有游戏能够拥有像《命令与征服3》一样庞大的预算,完全使用过场动画来讲述故事。在《冲突世界》中,我们极力打破‘游戏玩法’与‘故事’之间的界限。许多重大事件均发生于游戏玩法中,而这恰好也是一种更节省资源的方法。不过RTS游戏中的故事讲述一般发生在任务开始之前。主要原因包括:

首先,这并不仅是RTS游戏中的现象,因为要将角色动机转变成富有吸引力的玩法并非易事。事实上,在令角色置身于某种‘必须存活下来’的故事场景中,可以让玩家执行的有趣操作,基本上不是角色真正会做的事情。”。

电影感

对我来说,《冲突世界》的电影感要强于其他多数RTS游戏,但我却无法解释其中原因。

《冲突世界》当然采用了游戏内交流、不停改变目标和动机等手法,而《最高指挥官》和《横扫千军》等游戏也不例外。虽然后两者也同样是我最爱的RTS游戏,但我却并不认为它们的呈现方式与《冲突世界》一样充满电影感。

对我而言,好莱坞呈现方式就是《冲突世界》的主要魅力之一,它是游戏成功及独特的关键因素,我对这一现象颇感困惑,只能向Magnus寻求解释:

“我们没有在《冲突世界》中植入建设基地或搜集资源的机制,所以我们的角色在游戏玩法中的所做所为,更接近于他们在现实生活或电影中的行动。”

这就是问题的关键吗?我怀疑确实如此,而故事的叙述方式以及玩家的游戏行动之间也确实颇有关联。在现实战争情境中,将军不可能去监管搭帐蓬这种琐事,也不会每隔10分钟就随便进行一次核弹攻击。真正的将军更可能是大规模地调兵遣将,思考战斗策略。搞建设是工程师的事情而不是军人的任务。

游戏设计要取材于真实游戏(游戏邦注:即通过游戏玩法支持玩家扮演现实中的某个角色,同时又让游戏不失趣味性),但这一基本原则似乎已被许多开发者所遗忘。

问题在于,游戏玩法与故事元素通常难以融为一体。现实战争环境中的将军可能只是在桌面移动了一些棋子,而部队资源和数量非但不在其掌控范围之列,而且难以在短期内加速增长。并且他们制定的每一个决策还会遇到军队士气、疲倦和疾病等问题。总之,真实的战争绝非好玩的游戏题材。

与此同时,各类游戏都有自身可让游戏好玩而又不失易用性的幻想元素。在第一人称射击游戏(FPS)中,玩法必须拥有自愈能力,他们自然而然地认为战场中应该四处散布着急救药箱,他们将这种事情视为游戏设计的一个环节,并且是保证游戏公平性的重要元素。

这类问题与故事是否给《冲突世界》开发团队带来了麻烦?Magnus表示:

“你只要无视它就行。玩家通常都知道游戏中必须有什么想象内容。无论你的游戏呈现多少硬核或真实感,它仍然会充满大量不真实和妥协性的内容。”

视角

RTS游戏中最明显的设计幻想体现就是视角。这类游戏经常使用上下视角,从《Stonkers》、《沙丘2》到《地下城守护者》、《主题医院》莫不如此。

现代游戏常给予玩家更多场景控制权,但就算你可以彻底缩放《命令与征服3》,事实也并非如此。几乎所有的RTS游戏玩家都表示,他们希望尽可能地看到更多战况。《冲突世界》和《最高指挥官》甚至特意为此提供了多个监视器,以便在额外屏幕上呈现整个策略地图。

虽然Magnus已经表示设计师制作好玩的游戏时,通常会忽视这些游戏幻想,但我仍想知道更多相关内容,想了解视角如何影响故事发展,究竟是故事决定呈现方式,还是呈现方式主导故事发展?

“我们今天看到的多数游戏类型诞生时还未引入真正的故事叙述内容,通常情况下,故事需配合呈现方式而不是相反。例如在RTS游戏中,你在云端高飞鸟瞰时,如果没有切换摄像镜头并迫使玩家去观看,屏幕就没有什么必要呈现地面玩家之间的故事。”

“而在《半条命》等此类将玩家禁锢于一个相对狭仄空间、周围频繁上演玩家之间搏斗场景的FPS游戏中,设计师并不需要控制玩家的视角,因为玩家基本上不可能错过自己视线范围中的内容,除非他们有意忽略。”

对Magnus来说,把握故事与趣味之间的平衡最为关键。鸟瞰角度未必反映真实情况,也没有人认为它更易呈现故事内容,但它确实令新手更易掌握RTS游戏,也是铁杆玩家更为熟悉的视角。它将整个游戏体验置于一个容易理解的情境中,为玩家提供了一个可总览全局的安全视角。

标准的RTS视角也很适合多数RTS游戏的场景范围。在战略游戏中,你常会同时进行建设营地、应付两三场伏击战,监视军队防御情况等操作。无论你是在《冲突战争》中进行焦土策略,在《最高指挥官》中指挥机器人,还是在《地下城守护者》中摧毁Dark Mistress——所有的战略游戏都有很宏大的场景范围。

但即使是《冲突世界》中的场景范围和故事背景也要与玩法相妥协。

“没错,你一开始就得推出一场大战役。如果你使用当代故事背景就难以达到这一效果,所有的历史和科幻题材游戏都不例外。我们在《冲突世界》中以冷战为背景,因为这是在时间上距离我们最近,并且最有可能发生战乱,同时又能保留一点可信度的时期。”

“但你一定不要忘记,这是一款动作而非模拟游戏。这可以解释为何我们要在游戏中采取让苏联进攻美国这种看似并不可信的做法。在这里,轰炸郊区的趣味性要超过美国大陆被攻占的真实性。”

“但也要避免过犹不及的情况。单人战役的关键任务当然要比战争的结果更重要,但设置一些无关最高指挥部的任务也未尝不是可取做法。假如每个任务都如此重要,这可能就会让玩家对任务感到麻木,所以我们选择关注角色内心的矛盾和实际战争,而非全球冲突的结局。”

“为游戏设定一个服务于玩法的故事背景,就有可能在增强游戏玩法的同时,讲述一个精彩的故事。有些游戏的故事实际上就是玩法,这会增加游戏的复杂性。但这也正是多数RTS游戏获得成功的原因。”

故事创作

我们已经了解游戏故事背景是根据设计师的意图来设计,但游戏设计又是如何组织成形的?

组织整合一款电子游戏绝非易事——你需要一个拥有多个部门的大型团队,并且他们所有人都要听命于同一个设计理念。故事文案负责撰写剧情脚本,美工设计人物和场景,程序员编写关卡和角色动作,测试人员得确保一切工作成果运行无误,但即便是这样也难免百密一疏的结果。

另外,这还只是一种简化版本的游戏开发流程。

不同公司所运用的游戏设计方法各不相同,例如Free Radical Design会专门挑选一名文案根据开发团队已经敲定的想法撰写故事内容,充实角色形象。Telltale Games则拥有不少擅长写作的主设计师和创始人,他们可负责完成《妙探闯通关》搞笑的剧情。Quantic Dream(游戏邦注:代表作包括《暴雨》、《Omicron》和《Fahrenheit》)团队则由David Cage这名自诩为导演而非设计师的多面手,全权负责游戏项目的各个层面。

那么《冲突世界》的开发团队又是如何确立并丰富游戏的故事元素?Magnus的回答如下:

“情况很复杂,一言难尽。我们有许多人都参与了主要事件及人物原型初稿创建过程。游戏中的日常对话和单人玩家的故事脚本大部分是由内部故事写手Christofer Emgård完成——但这并不包括单位对话。还有许多其他对话是由设计团队的不同人创作完成的。”

“关于游戏的故事创作倒有点像是先有蛋还是先有鸡的问题。如果没有故事你就无法设置地理场景,但你又需要一些合适的地图辅助故事创作。从故事角度来看,出色的游戏玩法需具备一定的可信度,但有时候又不能让故事情节过于喧宾夺主。”

“从营销人员、高级管理层、引擎程序员到社区团队,人人都需要知晓故事的每天进展。所以我们尽己所能地进行沟通和交流,但做到这一点真的很难。因为你每天能吸收消化的内容真的很有限。”

“美术和关卡设计团队要与设计保持同步,撰写故事的人员也要每天跟进最新进展,以免在已经被抛弃的关卡上浪费过多时间。”

他们为何要采用让多名文案与设计师、程序员同时打交道这种方法的确让人困惑,让一些专职文案负责所有的叙事内容,不是比分散大家精力的做法更有效吗?Magnus是否也曾因团队的这种做法而感到焦头烂额?

“我们与小说作家Larry Bond和电视剧本作者Ed Zuckerman共同开发《冲突世界》,说实话我觉得跟他们共事真的很愉快。我认为与这种作家“大腕”合作正是我们开发过程中的一大动力。”

“对公司上级管理层来说,这意味着我们的游戏多少拥有一些“品质保证”。对我们开发者来说,我们关心的是制作一款好游戏,而这两者的专长和经验恰好有助于我们实现这一目标。Larry Bond帮助我们重现具有极高可信度的战争场景,Ed Zuckerman帮助我们完善了角色和其他写作细节。”

多人模式及大众用户

RTS故事元素的主要优势之一并不在于单人游戏模式,而是多人游戏体验。

在FPS多人游戏中,玩家通常无法获得什么丰富的游戏体验,因为他们走过的路程,所用的策略与其他人并无区别。而带有策略元素的FPS游戏(例如《反恐精英》、《战地》或《军团要塞2》中)却往往更容易形成故事。因为玩家可以在游戏中讨论组队玩法,选择武器和获取点数。

RTS游戏则将这一特点引向新高度,支持玩家组成正式而灵活的联盟。玩家并不需要局限于恐怖分子或反恐部队这两种选择,他们可与其他玩家组队,组建爱国帮派叛离其他组织。玩家在多人游戏中拥有更多创造自我故事的工具。

Magnus对此似乎认为,从这一方面上看,RTS游戏应排在末位。他指出MMO游戏更擅长此道,不管游戏中植入多少社区创建工具,由玩家生成的故事仍是MMO对玩家的最大吸引力。

有许多开发商试图将成功的MMO模式引进更为大型而休闲的掌机游戏领域,《最高指挥官》等掌机平台的RTS游戏也在尝试这一做法,那么转移平台是否会导致游戏风格或操作输入方式发生变化?

Magnus认为,“游戏故事设计应该不会有什么明显变化。我认为Xbox版本的《冲突世界》不会有太大变动。从设计角度来看,RTS并不是掌机设备的理想搭档。有许多游戏理念都是诞生于以鼠标为主要输入方式的操作环境。”

他指出了Xbox 360版《冲突世界》的一些总体设计变化,例如该版本中没有烟雾战以及FPS摄像视角。我认为这种做法是为了迎合大众用户对快速上手、更休闲化游戏的需求,那么此类游戏题材是否会走向指向点击风格,或者休闲变革的趋势?

Magnus的看法是“我认为将来由大型开发商推出,并以鼠标为主要输入装置的新款RTS游戏(或新游戏理念)不会太多了。这与PC平台AAA游戏销量不济有很大的关系。”

这令我不禁想起今后游戏题材的融合趋势,其中的一个独特典型就是RTS与RPG的结合,但Magnus认为真正持久的在线世界将更为有趣,它的诞生将对未来的RTS产生更广泛的影响。(本文为游戏邦/gamerboom.com编译,拒绝任何不保留版权的转载,如需转载请联系:游戏邦)

How to write…a Strategy game

by Joe Martin

I have a confession to make. When I first started writing this continuing feature, which happened shortly after I started working at bit-tech, I didn’t really have a long-term plan of what to write about. I pretty much just wanted an excuse to show off to Tim that I could write a gamers equivalent of a technical review of a graphics card. Something long, credible and as technical as possible.

Still, by the time the first instalment was complete I had realised two things. The first was that it didn’t matter how clever I tried to be because I still would never be able to top Tim in a jargon-off. The second was that I may have actually stumbled in to a topic which was both interesting and important.

Ever since Half-Life first managed to show the mass audiences that computer games could tackle story in an intelligent and immersive manner without becoming one of those scary Dungeons and Dragons adventures that endless horror stories are told about, “story” has become a big buzzword in the games industry. It’s something that Half-Life 2 would later re-enforce, making “physics” the next big buzzword for publishers.

Magnus Jensen was lead designer on World In Conflict

Since then it seems like games of all types and sizes are trying to claim that they have epic stories and fantastic characters. Gabe Newell and Co. managed to teach publishers like Take-Two and EA a brand new word of supreme importance: Narrative.

The problem though has been that not all games have actually delivered on their promises and that not every type of game can realistically provide a vehicle for the telling of stories. Some genres can do story really well and others can’t – it’s a plain fact and you wouldn’t expect to see a Breakout clone with a romantic tragedy for a plot, would you?

So, in this third instalment in my now re-focused and less selfish series I’m going to be looking at Real-Time Strategy games and try to see how they are written, what stories they can tell well and how they may change in the future. Helping me out along the way is Magnus Jensen, lead designer on the fantastic World in Conflict.

There’s only one man more important than Magnus in RTS games, y’know…

World in Conflict is an especially interesting game to use for a case-study since it basically re-wrote a lot of the rules for how stories are told and what stories are told in RTS games. In a time when most titles in the genre are still using talking heads or, at best, acted-out FMVs between missions, World in Conflict used a mixture of scales to engage players. During gameplay players will be fighting in battles which determine the course of a war, but in between you’ll be embroiled in the much more claustrophobic side of the war – up close with the troops, exposed to their personal battles.

What goes into an RTS game? Do well-known authors like Tom Clancy bring anything worthwhile to a developing title and can any RTS game win our hearts without Joe Kucan? Enough with the questions! It’s time for answers!

Getting to know you…

The Real-Time Strategy is one of the easiest game genres to chart the history of because, although the genre does disappear back into obscure titles like Stonkers on the ZX Spectrum (don’t fail me now, Wikipedia) the first real RTS games as we understand them now didn’t appear until much, much later.

It’s no surprise that Westwood Studios was responsible for inventing what many regard as the grandfather of modern strategy – Dune II: Building a Dynasty. The very same developer would later go on to create the Command & Conquer series, which still stands as one of the forefathers of modern gaming. Developed in 1992, Dune II was the sequel to the RTS/Adventure hybrid Dune and was only loosely based on the Frank Herbert epic of the same name.

Being a massive fan of the book and the first game, Dune II was also one of the first games I played on my Amiga A500+ as a geek-in-training, so naturally it’s one which I know intimately.

As a franchise, Dune contains all the important elements needed for an RTS game too and Westwood couldn’t have picked a better novel to use as a basis for their game – the novel easily supplies the resource players must gather (Spice Melange), clearly defined foes to defeat and a long, epic plot which allows for numerous massive conflicts. The book itself even mentions Kanly, a series of rules which govern the types of allowed warfare in the fictional universe.

From Dune onwards it was a hell of a lot more difficult to work deep storylines into RTS games though. Developers didn’t have the same established framework to cling to – although they had a much clearer idea of what worked and what needed to be there. That simple fact shows in later games too.The C&C story, while admirable and impressive by gaming standards, doesn’t quite compare to the intricacies of the Dune novels. The gameplay of Command & Conquer however is infinitely refined over Dune II.

Dune II was the game that started it all, but RTS come in all shapes and sizes…

So, if we simplify matters by weeding out the lesser games and inevitable Dune II clones, we ostensensibly were moved from a great gameplay style with an awesome story, to an even greater set of game mechanics but with a slightly lesser story. But did it matter? The story was lesser, but the gameplay was infinitely improved and the decreased focus on micromanaging an army opened up later RTS games in a way nobody could have anticipated. The RTS exploded onto PCs successfully and earlier games like Stonkers which had taken inaccurate stabs at the format were left forgotten by the wayside.

So, just how important is story to a Real-Time Strategy game anyway? If Command & Conquer could do so well by balancing story and gameplay out like that then how do other designers work to find that balance for their own games? Is it proof that gameplay is more important than plot for this genre? I put the question to Magnus to try and see how important he thinks story is to RTS games in general and how pivotal it was to the success of World in Conflict.

“My initial thought is that RTS games are usually no different than any other games when it comes to gameplay vs. story. The endless discussions and GDC lectures that have been held on the topic in defence of either side applies to RTS games as well as other genres.” Magnus said, though he first chose to lament the impossible scope of my questioning.

“In World in Conflict though the story is extremely important,” he continued. “Single player is very much a linear, emotional ride (compared to the cerebral nature of classical RTS games). If you strip away the story from our single-player mode, you’re left with something quite shallow when compared to most other RTS games offerings.”

FMV mission briefings are considered a staple of the genre by many

Maybe it’s more to do with how the story is told, I realised. How do designers decide to communicate the story and objectives to a player anyway? Mission briefings are the logical way to accomplish this and briefings are more ideally suited to RTS games than they are to some other genres. It’d be a very boring version of Duke Nukem 3D that gave you a five-minute briefing before every enemy! (unless it had strippers giving it – Ed)

Increasingly though RTS games are moving storytelling into the gameplay itself, issuing objectives and narrative in the middle of game events to increase the sense of drama and panic – just look at how many times Jennifer Morrison pops her head up in Command & Conquer: Tiberium Wars if you don’t believe me!

“Cutscenes are typically very expensive to make in terms of development resources, so the story is also sometimes told in briefings with just voices and/or talking heads. Very few games have the budget to tell the whole story in full cutscenes, like C&C3.,” said Magnus. “In World in Conflict we tried to break down as many of the barriers between ‘gameplay’ and ‘story’ as possible. A lot of the pivotal events happen while playing. The fact that this is much cheaper in terms of resources is just a happy coincidence. Generally though in RTSs, yes, the story does kind of stop at the doorstep when the mission starts. There are a few reasons why this is true.”

“First, and this is true not just for RTS games, it’s quite often hard to get the motivations of the characters (story-wise) to translate into good gameplay. In fact, outside of stories that put the character in a ‘get the f*** out alive at all costs’ kind of scenario, the things that are fun for the player to let the character do are generally not what the character would realistically be doing. For classic RTS games, this translates into the problem of ‘the guy commanding the army is usually not in charge of building the hardware itself’.”

Lights, Camera, Action

It seemed to me that World In Conflict was a game which had a more cinematic feel than most other RTS games, but the information I’d elicited so far didn’t really help me pin down why that was.

Sure, World in Conflict makes use of in-game communication, changing objectives and motives on the fly – but so do games like Supreme Commander and Total Annihilation. While those two are still fantastic games which would definitely stand on my ‘Best RTS Games Ever’ list, I didn’t feel that their presentation was as cinematic and movie-like as World in Conflict.

For me, that Hollywood presentation was one of the main appeals of World in Conflict – key to the games success and part of what made it so unique. It frustrated me that I couldn’t pinpoint why, so I went begging to Magnus for insight.

“In World in Conflict we have no base building or resource gathering, so what our characters do during the gameplay parts is much closer to what they would be doing in reality or in a movie.”

Could that be the key? I suspected so and it was clear that there’s a link between how the story is told and the players actual in-game actions. In a real war situation the Generals aren’t likely going to be in charge of erecting tents and casually launching nuclear strikes every ten minutes. Instead, a real General would more likely be found directing troops and units on a large scale and thinking of the battle ahead. Building is for engineers, not warlords.

Realism isn’t important for all strategy games though, as Black and White proved

The fact that the player is a closer mirror of their assumed identity means that they are pulled closer into the action and more fully immersed. Combine this with the dramatic pacing of the story itself and the fact that complex characters are quickly built around the player from the offset, such as Bannon and Sawyer, and the cinematic effect becomes inevitable.

It’s a fundamental rule for game design in realistic games really – to have the players role as close to the reality of that role as the gameplay allows (and while still making the game fun) – but it’s one which many developers seem to have forgotten.

The problem is that the gameplay and the story are often hard to join together. The true reality is that a wartime General may be doing little more than moving pieces on a board in some cases, with troop resources and numbers not only out of his control but very hard to accelerate in the short term. There’s morale, fatigue and disease to contend with in every decision and choice – in short, the reality of war wouldn’t make a fun game.

World In Conflict sought to balance personal stories with focused gameplay

At the same time though, all genres come with their own conceits which are an important and integral part to making the game both fun and accessible. In FPS games players have to be able to heal themselves and the fact that first aid kits are lying all over the battlefield rarely enters into the mind of the player, who accepts that such things are a facet of game design and are needed in order to build a fair game.

I was interested to know if balancing these game issues with story posed any trouble for Magnus and his team.

“You just ignore it, basically. Gamers know that there have to be conceits for a game to ever happen. No matter how hardcore/realistic you make a game, it’s still shock full of unrealism and outrageous compromises.”

Head In The Clouds

The largest design conceit in RTS games is the most obvious one – the viewpoint. RTS games have always used a top-down perspective of one kind or another, from Stonkers and Dune II right through Dungeon Keeper and Theme Hospital into the present day.

Modern games tend to give the player more control over the scene, true, but even though you can zoom all the way in in Tiberium Wars doesn’t mean that you do – nearly all gamers will acknowledge that in an RTS game you generally want to see as much of the battlefield as possible. World in Conflict and Supreme Commander even went the extra step of providing multi-monitor support so that full tactical maps could be displayed on the extra screens.

Although Magnus had already told me that designers basically have to ignore these gaming conceits in order to create a game which is fun to play, I still wanted to know more. I wanted to know how the viewpoint specifically might affect the story. Was the story dictating the presentation or the other way around?

“Most of the genres we’re seeing in the charts today precede the advent of real storytelling, it’s usually the case that the story has to adapt to the presentation and not the other way around,” Magnus admitted. “In RTS games, for instance, you’re flying around high up in the clouds with a bird’s perspective. It would not make a lot of sense to have person-to-person drama played out on the ground (with facial animations, etc.) without taking control of the camera and forcing the player to watch.”

Early RTS games didn’t have such simple designs – in Dune I players had to recruit troops in person!

“Compare that to FPS games such as Half-Life, where you can lock the player into a relatively confined space and have people-to-people drama play out right there in the room with you. Under such circumstances the designer doesn’t have to take control of the players camera since there is practically zero likelihood of players missing the fact that there is something happening unless they do it deliberately.”

Again, finding the balance between story and fun seemed to be the most important thing to Magnus. The birds-eye viewpoint may not be truly representative of the reality, nor does anybody really try to explain it story-wise – but it makes the game accessible to RTS newcomers and familiar to RTS veterans. It puts the whole experience in an understandable context and gives a safe, established point from which the rest of the game can be exposited.

The standard RTS viewpoint is also fitting given the sheer scope of most RTS games. Often in a strategy game you’ll be using your ability to multitask – building a camp, fighting two or three skirmishes at once and trying to monitor your defences too. It doesn’t matter whether you’re laying scorched earth in World in Conflict, directing a giant robot in Supreme Commander or torturing your Dark Mistress in Dungeon Keeper – all strategy games tend to have an epic scope.

Magnus blames real world events for the lack of contemporary RTS games

It turned out that even the scope and setting of the war in World In Conflict was subject to the vs. gameplay tradeoff.

“Yeah, you need a big friggin’ war for starters. And those aren’t easy to come by if you want to use a present-day setting, hence all the historical and sci-fi games. In fact, us going with the Cold War for World in Conflict was dictated by the fact that this was the closest period in time we could find when there could have been fighting on the scale needed while retaining some shred of plausibility,” Magnus told me.

“But you must never lose sight of the fact that it’s an action game and not a simulator. That’s why we had the Soviet invade the US knowing full well that it wasn’t very plausible at all. The fun of blowing up suburbia basically outranked the concern for how realistic a US mainland invasion really was.”

“You can over-do it though. The key missions in the single-player campaign are of course important to the outcome of the war but it’s nice to have missions that high command doesn’t care that much about. If every mission was so important then it would de-sensitise the player, so we chose to focus on the character’s internal conflicts and actual battles instead of the outcome of a global conflict”

“Make a setting that serves your gameplay, and then you make as good a story you possibly can while still enhancing gameplay. In some games the story pretty much is the gameplay, which further complicates things. But that’s basically how most RTS games work at least,” Magnus summed up.

The Pen Is Mightier

So, now we know how the story is designed in terms of the considerations involved for the designers, but what about how the game design is organised?

It’s a tough task to organise a video game – you’ve usually got a large team spread over numerous departments and all of them have to adhere to a singular vision which may or may not be yours. You need writers to write the script, artists to design the characters and locations, programmers to make the levels and characters work, testers to make sure it all works and even then it may not work that well at all.

Plus, that’s just the simplified way of looking at it.

I’ve chatted with writers and designers from a number of companies in the process of writing this feature and I’ve found that approaches tend to vary wildly. Free Radical Design handpicked a writer for their game design to flesh out the characters and approach for an idea they had already settled on (Haze).

Telltale Games meanwhile is lucky to have lead designers and founders who are also the the lead writers for the hilarious Sam and Max episodes. Quantic Dream (Fahrenheit / Omicron / Heavy Rain) meanwhile has David Cage, a man who dips in and out of every aspect of his games and sees himself as more of a director than a designer.

So, how was the development team for World in Conflict organised and how was the story and plot established and fleshed out? As usual, Magnus has answers for us.

Realism is about more than just using the colour brown a lot

“It’s complicated,” he confessed. I settled in for the long haul. “There’s a handful of people involved in the initial crafting of the main events and rough character descriptions. The day-to-day writing of dialogue and scripts for single player was mostly done by our in-house writer Christofer Emgård – but that doesn’t include all the unit dialogue. That, and a lot of other dialogue is created by various people on the design team who all work on a number of areas.”

“The story creation though is something of a chicken and egg situation. You can’t set the locations without a story, but you want the story to come up with suitable maps. Cool gameplay events need to be plausible from a story perspective, but sometimes the story will have to abide if it’s an awesome enough set piece.”

“Everyone, from marketing to upper management to engine coders to community team, benefits from having an up-to-date grasp of the story. So we try to communicate it the best we can, but it’s hard. There is only so much you can take in on any given day.

“The art and level teams synchronise with the design and story guys on a daily basis though, to avoid wasting time on levels that get cut.”

War may be a popular topic, but it turns out that compromise is the key to good game design

I wondered why the development team was organised this way, with multiple writers on the project juggling responsibilities with designers and programmers. Surely it would be easier to have a handful of established writers taking charge of all narrative rather then letting the idea by diluted? Or had Magnus been burned by such an approach in the past?

“We worked with both author Larry Bond and TV writer Ed Zuckerman on World in Conflict, and I’m not lying or kissing ass when I say they were a joy to work with. I think the motivations for getting a “big shot” writer on board differs throughout the organisation though.”

“To upper management it provides some form of “seal of quality”, and who can blame them for not completely trusting Swedish nerds with tens of millions of dollars? For us, the developer, it’s all about creating a great game, and those guys have the skill and experience to help you do just that. Larry Bond helped us getting the war and the scenarios as plausible as possible and Ed Zuckerman helped us with the characters and nitty-gritty writing.”

OK – no fingers burned after all.

Multiplayer and Mass Audiences

One of the main strengths of an RTS story-wise comes not from the singleplayer experience, but the multiplayer experience.

Think about it. In a FPS multiplayer game players often struggle to come away with meaningful stories of their exploits because they are essentially running through the same routes and tactics that everyone else is. In FPS games with a strategy bent – Counter-Strike, Battlefield or Team Fortress 2, for example – stories are easier to create. Players can talk about teamplay, pincer movements, chosen weapons and capture points.

RTS games often take that to the next level, allowing players to form formal yet fluid alliances which can play key roles in deciding a match. Players don’t need to be restricted to the Terrorist or Counter-Terrorist teams. They can team up with other gamers, form nation-like clans and betray one another spectacularly. There are more tools at the players disposal for creating their own dramas in multiplayer games.

When I broached this idea with Magnus though, he seemed to think that RTS games are at the back of the queue in this regard. He pointed out that MMO games are even better at proving that concept and that no matter how much community building features were integrated in the game players would always prefer MMOs for player generated stories.

With a number of developers looking to bring the success of an MMO format to the large, more casual console market though, another thought popped into my head. What about RTS games on a console? C-RTS games are trying to kick off more properly now, with Supreme Commander and a few other franchises attempt to bring the genre to a wider and not as pirated format. Does a change in platform cause a change in style, or just inputs?

Many RTS games are moving to consoles now in a push to capture the larger market

With an Xbox 360 version of World in Conflict set for a 2008 release, I asked Magnus how he felt on the matter.

“There should be very little difference in story design. I can’t think of anything major we’re doing, anyway, when it comes to the Xbox version. Design-wise though, the standard RTS is a poor fit for consoles. A lot of the concepts were born and raised in an environment where the mouse was your main input device.”

Magnus went on to outline a few of the key differences in the overall design of the game – no fog of war and FPS controls for the camera – and it occurred to me that a lot of the challenge lay in simplifying the genre enough. Whether it was being simplified for the gamepad control system or simplified for the more casual gamer console audiences wasn’t something I wanted to hazard a guess about. That said, I think the desire for quicker and more casual games in mainstream audiences is pretty obvious. Looking forward into the future of the genre then, I wanted to know Magnus’ predictions. Would the genre go the way of the point and click, or would it undergo a casual revolution?

RTS game design differs heavily from other genres

“I think that we’ll see very few new RTS games (new concepts) from the big players that are built around the mouse being its primary input device. This of course due to the economical fact that PC sales alone have a hard time carrying a AAA game,” said Magnus.

I raised the idea of possible genre fusions and hybrid games in the future as the boundaries between games broke down more. One of the things which seemed unique to me was an RTS/RPG, but Magnus saw the birth of truly persistent online worlds as being more interesting and possibly having a massive effect on the future of RTS games. Could an MMO/RTS be on the horizon?

Well, maybe. Magnus didn’t give anything away on that front and I didn’t want to press the issue. What was clear though was that not only had the RTS genre come a long way in recent years thanks to the high quality of key strategy games like Supreme Commander and World in Conflict, but Magnus also saw a bright and interesting future for the genre.

“While I’d like to claim brilliance on our part (and I do think we’ve pushed the RTS genre forward), it’s probably got more to do with the general maturing of the industry. Compare the complexity in personality and motives of a villain from 1998 with that of a villain from 2007 in pretty much any genre with story and you’ll usually find improvements across the board.”

Thanks for reading. In the next part of this on-going series we’ll be moving on from strategy games to tackle a wildly different type of game: RPG. How are RPG games designed and written? How are the complex rule-sets used to complement plot and narrative? Those are the questions we’ll be answering.(source:bit-tech)

闽公网安备35020302001549号

闽公网安备35020302001549号