关于游戏IAP设定与儿童玩家误消费问题的探讨

作者:Richard Stanton

Nathan Ditum已经做了10年的游戏记者,现在他与妻子和其他家人住在英国。当他的儿子9岁的时候,Ditum送给他一台iPod Touch。而那也是麻烦的开始。

Ditum说道:“那是一款名为《Fantasy Manager》的免费足球游戏,也是引起问题的根源。在之后的某一天,当我自己在玩游戏时,打开手机并收到了一封23英镑(38.5美元)的App Store账单。”

当Ditum在研究该账单时,他又收到另外一笔费用。一笔接着一笔,他共收到将近200美元的账单。

“我简直吓坏了,我立刻打电话给妻子,她询问了我们的儿子,但是他却表示并未做任何事。”

美国联邦贸易委员会在听取了来自家长(他们的孩子在App Store中进行了应用内部购买)的“无数抱怨”后对苹果展开调查。在许多游戏中都带有应用内部购买,并经常伴随着免费业务模式,可以换取扩展包,订阅内容以及付费货币。

这些购买远远超过了预算。有一名儿童便花费了6000多美元于名为《蓝精灵村庄》这款游戏中,这样的故事导致如今游戏产业中充满了“账单震撼”这样的说法。引起广泛关注的IAP让人们开始注意到这样的极端,而逐渐忽视了像Ditums等家庭所遇到的较常见的问题。

Ditum说道:“我回到家并让儿子解释他到底做了什么。通常情况下在《Fantasy Manager》中,你需要购买名为‘shields’的货币,但是游戏却并未将其与真钱清楚地联系在一起。你知道有一些蓝色对话框会提醒你需要购买100个shields或其它东西。这样的文本隐藏了其联系,所以才会导致一个9岁的儿童在短短几分钟内花了100多英镑。”

在发现发生了什么事后,Ditum采取了其他家长并未做到的方法—-继续联系苹果,并找到了在From the Bench《Fantasy Manager》的开发者。“我找到了他的电子邮件并联系他,向他传达了我的不满,让他清楚自己和苹果所困扰我的问题是围绕着密码的问题。”

困扰Ditum的是,不管是他还是妻子都不知道进入设备的密码,所以他们的儿子也不可能知道。这个家庭有好几台苹果设备,这是可能的原因,但是却不能解释这些IAP是如何进行的。

Ditum说道:“他们都不想解释这一问题。只是退了钱而已。”他们拒绝进一步讨论问题。

然而事情并未这么结束。再一次收到账单后,银行冻结了Ditum的账号,认为这次的交易存在可疑性。

Ditum说道:“这本身就是一个标志不是吗?如果IAP能够出现在一个致力于识别信用卡诈骗的系统中,这便在暗示着一些问题。”

儿童的游戏

面向儿童们的游戏开发商Toca Boca的CEO兼联合创始人Bjorn Jeffery说道:“为了在免费游戏中获得成功,你必须创造一些带有游戏化且伴随着虚构约束的内容,然后你便可以通过花更多钱去推动游戏的发展。”

“这与尝试着创造一些儿童们会喜欢的内容是截然不同的。”

自从2010年以来,总部位于斯德哥尔摩的Toca Boca的游戏便累积了超过5000万的下载,获得了无数奖励以及5颗星的评级。Toca Boca将其广受好评的作品称为“玩具”,因为它们并不具有明显的游戏装置,如关卡和前进系统。

举个例子来说,《Toca Band》提供给玩家一个舞台以及多个角色,然后让他们能够混合并匹配舞台设置,从而基于无数编曲去演奏一首歌。Toca Boca的游戏是基于事先成本进行出售,并不包含应用内部购买,而创造Jeffery所谓的“健康利润”。作为面向儿童们的应用开发商,这样的工作室真的只是少数。

Jeffery说道:“对于Toca Boca,免费游戏是在我们开始前就计划好了。我们很快就意识到IAP对于许多家长来说将会是个痛处,会带给他们不安全感,就像‘当我给儿童这台设备后会发生什么呢?’这便是我们想要改变的一点。不幸的是,情况好像并未发生多大的变化。”

免费游戏业务模式是一种变量,即先让消费者玩游戏,然后再通过广告,或者IAP进行营利。后面的购买方法(到2013年12月为止)占据了92%的App Store收益以及95%的Google Play收益。随着这些平台不断进入更多家庭(55%的美国成人拥有一台智能手机,42%拥有一台平板电脑),免费模式不断主导着儿童们的游戏。

Jeffery说道:“面向儿童的免费游戏领域具有强大的掠夺性。有许多开发者其实在做着那些他们自己也知道并不正确的事。这既具有掠夺性,同时也是非常赚钱的。我们一年制作了6款应用。而像TabTale这样的公司能够制作200款。这就像是一台机器,一台免费转换机器。”

多少?

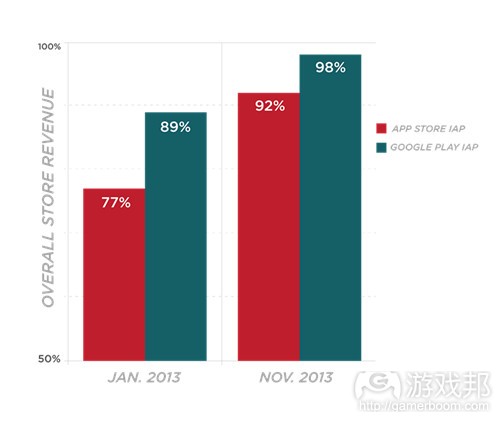

IAP是推动手机收入获得巨大提升的原因。外部应用分析平台Distimo关于2013年的报告表示,在2013年1月,77%的App Store收益是源自IAP;直到2013年11月,该数据增加到了92%。Google Play上的IAP在同一时期的总收益百分比也从89%增加到了98%。这让IAP成为了应用中最大的单一收益来源。2013年App Store的收益是100亿美元,保守估计的话,单单在iOS平台上,免费游戏市场的价值便是60亿美元一年。

《Moshi Monsters Village》

Mind Candy的CEO兼创意总监Michael Acton Smith OBE说道:“重点是我们很难基于一个预付价格去创造一款面向儿童的成功手机游戏。App Store上的许多游戏都是带有IAP的免费游戏。”

《Moshi Monsters Village》是Mind Candy第一款免费游戏,发行于2013年12月24日;其第二款免费游戏《Moshi Karts》紧接着发行于2014年2月。《Moshi Monsters Village》是一款城镇建造游戏;一开始你只拥有一只怪物,随着时间的发展你将收集更多怪物并为它们创建一个村庄。

游戏系统是围绕着免费游戏原则进行构建:玩家先从少量的付费货币开始,很快地他们便知道可以使用这些货币去加快建造速度。游戏中存在计时器,能够限制特定活动的能量仪表以及在建造成本上的巨大变化。这是针对于区分并人为减慢玩家进程的设计,如此便能够诱导玩家通过IAP去购买推进道具。

这是一款针对于儿童们的游戏。这同样也是在鼓励玩家花钱的游戏。这些具有潜在矛盾的目标并未对Mind Candy或苹果造成影响。

作为面向平板电脑和智能手机发行的苹果iOS 7的一部分,苹果将儿童作为一种类别带到了App Store。它将应用划分成3个年龄范围,并要求它们遵守儿童在线隐私保护法,且对广告和数据收集实施一定的限制。根据苹果,被规划到这一部分的应用必须是“适合儿童的”。

iTunes上的儿童类别是经过精心设置的,不幸的是却未包含足够的应用。这里没有足够的空间去放置像《Memo’s Reef》或《SpongeBob Moves In》这样的免费游戏,出售付费货币的城市建造游戏以及像《My Little Pony:Friendship is Magic》(出售需要花费70美元付费货币的小马)等游戏。

Jeffery说道:“苹果基于指南创造儿童类别是一个好的开始。但不幸的是,有很多开发者并未选择这一类别。他们虽然在创造儿童的产品,但是为了避免这些限制而未将自己的产品置于这一类别中。”

来自Osborne Clarke的互动娱乐律师Jas Purewal说道:“关于怎样的游戏属于儿童游戏并不存在明确的规定。《愤怒的小鸟》,《割绳子》,《小鳄鱼爱洗澡》难道不都是儿童游戏吗?《割绳子》的评级是7+,所以我们可以将其当成是一款儿童游戏,但是如果你这么问别人,你可能会获得许多不同的答案。另一方面,Mind Candy的《Moshi Monsters Village》属于儿童游戏吗?这是几乎可以肯定是事。”

但是《Moshi Monsters Village》却不在App Store的儿童类别中。

《Candy Crush Saga》是最成功的免费游戏之一,我们可以从其开发商King最近的IPO中看到它的成功,即在2013年最后3个月时间里,玩家在其手机应用中共消费4.93亿美元(78%的人是在玩《Candy Crush Saga》)。迪士尼的《Frozen Free Fall》是一款与儿童电影进行搭配的游戏,它复制了《Candy Crush Saga》的方式,并在某种程度上基于同样的节奏引进了同样的三消机制,为了同样的功能使用了可购买的升级道具,还使用了同样的进程结构,虽然它带有较少的关卡。迪士尼Interactive是世界上最大的传媒集团的分部,它基于2013年最大规模的一部儿童电影创造了搭配销售的免费游戏便证明了其通过用户获取了巨大的盈利。而《Frozen Free Fall》也未出现在苹果的儿童类别中。

在《Moshi Monsters Village》中,名为“Rox”的付费货币能够用于略过计时器或交换其它游戏内部货币。玩家是不可能忽视Rox菜单图标,因为它以最明显的形式呈现在玩家面前,伴随着其它图标并不具有的闪亮标识。Mind Candy宣称这对于13岁以下的玩家的作用是不同的,尽管这似乎非常适合7岁的玩家。

Simth说道:“我们广泛地测试了产品并发现未引起任何抱怨。实际上,我们的用户非常乐意支付额外的货币,我们所收到的反馈也都是正面的。用户应该成为设计决策的审判官。”

“如果儿童产品并不允许使用IAP,那么开发者所能够采取的经济模式便很少,从而很难再手机设备上为儿童用户创造非常棒的娱乐产品。这真的是一个让人很无奈的情况。”

法律与自律

免费游戏最早在20世纪90年代末期凸显于亚洲市场中,特别是在中国和韩国。如今西方开发者所面对的许多有关免费市场的问题已经被东方开发者们解决了。

2010年,韩国通过了相关法律,规定学龄儿童在早上12点至隔天早上8点之间禁止玩像《MapleStory》或《Mabinogi》等19款大受欢迎的MMOG—-这一法律被称为“关机法”或“灰姑娘法”。

来自《坦克世界》开发商Wargaming的全职经济学家Ramin Shokrizade说道:“在韩国,儿童的免费游戏面对更大的问题,所以他们会更重视这类型游戏。他们采取相当于社交安全号码的措施,即你必须在游戏前输入这些号码,这样便能够了解玩家几岁,从而决定你是否能够购买游戏,如果你是未成年人,你可以消费多少钱,甚至能玩多长时间的游戏等等。我认为这真的是很酷的设定。”

在这个例子中,韩国政府是在经过几年对于这些问题的咨询和研究后采取的行动;但是法律并不总是源于慎重的考虑。专攻虚拟经济的经济社会学家,同时也是牛津大学研究所的一名研究人员,以及Habbo和Mojang等公司的虚拟经济顾问的Vili Lehdonvirta教授说道:“就像在日本,之所以会出现kompu gacha机制便是因为媒体遭遇了道德恐慌。”

从根本上看,Kompu gacha机制就是一种赌博机制,即使用游戏内部的老虎机去分布各种玩家需要收集的道具,同时也包含“稀有”道具。根据日本的报纸《Yomiuri Shimbun》报道,便有用户花费超过50万美元去购买一些特殊的虚拟道具。

Lehdonvirta说道:“所以我们需要监管部门能够采取行动,并宣称这是非法的行为。突然间政府开始约束这些公司的做法。如果他们足够聪明的话—-面对许多关于gacha的讨论和公众的愤怒,他们便应该足够自律并通过自我控制去避免糟糕情况的发生。”

在西方市场关于瞄准儿童的免费游戏的道德恐慌是非常显著的。Lehdonvirta说道:“我不知道儿童游戏中的IAP将会发生些什么。但我认为产业如果能够自律的话便是一种很明智的做法。”

然而自律的前提是承认问题。迪士尼和Nickelodeon都开发了一系列儿童应用,包含了许多带有付费货币的免费游戏,我就不在本文进行评论了。

Shokrizade说道:“我认为如果没有监管者的参与,像迪士尼这样的公司是不会采取任何做法的。我对迪士尼施加了压力,并且不是只有我一个人在这么做。特别是考虑到他们真的带有一些非常具有攻击性的作品,我必须让他们意识到这点。”

在2013年10月,Shokrizade在巴拿马举办的International Consumer Protection and Enforcement Network中发表了演讲并在迪士尼代表面前演示了《Marvel Super Hero Squad Online》的免费机制。他还未看到任何关于问题所采取的行动。

Shokrizade说道:“我敢保证如果没有外在推动的话迪士尼是不可能去改善他们产品的质量的。”

在像手机游戏这样快速发展的领域中,有许多公司都在讨论匆忙做出的判断是否会适得其反。在前几周,欧洲委员会宣称将举办会议去讨论四个关于IAP的问题,其中一个便是“直接诱导儿童去购买道具。”采取进一步的行动也是有可能的,但是欧洲委员会最初的态度应该是尝试着在现有法律框架下行事。

Purewal说道:“所有的法律已经存在着。包括消费者保护法,数据保密法,IP法等等,但是它们在一个产业中的使用还不够成熟,仍然带有不确定性。起点总是关于我们拥有怎样的法律,调整者将如何使用现有的框架去获得想要的结果—-在这个例子中便是对于消费者的保护。”

我们很容易识别出IAP问题最大的利益相关者,也就是平台所有者。如果已经存在适当的法律,开发者便不会自愿限制自己的活动,Shokrizade相信门户本身以及像苹果的App Store这样的地方是法律必须进行干预的目标。

Shokrizade说道:“平台所有者是解决这一问题的唯一人选。如果每年会出现4万款全新应用,你便不可能通过评价每一款应用去决定它是否符合管理标准。但是如果平台所有者能够负责这项工作,一切便都是可行的。特别是如果平台所有者能够从每款应用中抽成30%,他们便更有兴趣去做到这点。”

让我们回到App Store的儿童部分以及像《Moshi Monsters Village》这样的游戏是如何避开它。

最近关于苹果和美国联邦贸易委员会之间的处理导致苹果需要偿还3250万美元给那些无意识地在IAP上花钱的孩子们的家长。但这一协议的条款并未直接提及所涉及的特定应用。

Shokrizade说道:“联邦贸易委员会的抱怨中有一些奇怪的内容能够帮助苹果彻底脱身。最让人讨厌的便是对于‘适合儿童的’游戏的描述。有非常少的游戏‘适合儿童’。但是儿童却在玩许许多多的游戏,这便是出现各种消费和滥用的原因。”

关于赔偿的解决方法是基于苹果自身对于受影响人数的估计。但是Shokrizade认为苹果并非这一数据的客观来源。

Shokrizade说道:“EEDAR才是数据的客观来源。”EEDAR最近发现,那些在自己的设备上完电子游戏的家长中,有80%的人的孩子也在他们的设备上完游戏。在这些孩子中,22%的人进行了非授权的应用内部购买,而当他们这么做后,他们便有可能花费比成人还多的钱于游戏中。

“0.13%的非授权购买率(苹果所提出的)与22%之间的区别在于苹果需要支付325千万美元的赔偿金以及他们本该支付的53万美元。”

成人

尽管本文是关于儿童游戏中的免费模式的使用,但是关于特定业务模式的技巧问题也能够延伸至成人用户身上。手机市场中的最高5%消费者被归为“鲸鱼用户”,像《Candy Crush Saga》和《部落战争》这样的游戏便是为了最大限度地利用这类型玩家的消费行为。

如此问题便形成了,除了儿童以外,这些用户是否也应该得到保护呢?与赌博产业相比较,因为有非常多人处于上瘾的风险中,所以这是受到严格管制的。关于特定的免费游戏技巧是否具有强制性是一个开放性问题,如果它们是这样的,那么我们又应该怎么做。到目前为止,产业一直隐藏在商业秘密中,但它也一直抵制可能具有各种道德和财政问题的相关领域的调查。

对于儿童的利用

像《Moshi Monsters Village》等游戏是围绕着广泛使用的免费游戏模板进行创造。不管是城市建造还是宠物收集或者赛车类型,免费游戏经常会提供伴随着全新视觉效果且已得到认证的业务模式。因为这是一种受到数据驱动的设计。

在互动娱乐产业中,数据收集真的很广泛;在某些游戏中,每一个单一的行动,特定屏幕或部分所花费的时间都会被记录下来。在这一领域中的每一家游戏公司都拥有一个致力于寻找人们如何玩自己的游戏,他们该如何调整设计从而获得盈利的“商业智能团队”。

缺乏建设性使用是严重瓶颈出现的标志—-这将在尝试着诱导最初投资的游戏中发挥作用,也许是伴随着一扇紧闭的门,在此之后玩家将更有可能再次消费。之前Zynga的执行者Roger Dickey曾经将这样的时刻描述为引起“有趣的痛苦”的时刻。

这些受数字牵引的设计,并结合着对于反馈越来越深刻的理解,意味着这些游戏已经将过去观察玩家行为变成尝试着去塑造玩家的行为。儿童是否会玩这些游戏,或者情况正好相反?

儿童与电子媒体互动的专家(游戏邦注:已经出版过超过25本关于这一主题的书籍)David Buckingham教授说道:“心理操纵术这一词有点杞人忧天了。你可以讨论我们读过的每一本关于心理操纵术的书或看过的每一部相关的电影。”

“那些拥有游戏经验的人都知道它们是如何运行的,系统是如何操作的。操纵意味着人们是模型般的存在,他们变成了所有全能系统的傀儡,这样的话我是不可能花钱购买的。”

Buckingham教授最近领导了一场关于英国政府的独立评价,名为“商业世界对于儿童幸福的影响。”他认为关于免费业务模式的焦点应该是关于儿童做什么,以及不理解什么。例如许多免费游戏是依赖于广告而不受IAP赚钱,但这却是具有侵略性的,孩子们也是这么想的。

Buckingham说道:“伴随着传统广告,许多证据证明儿童们理解广告是什么以及它的目标是什么。他们可以选择接受它或拒绝它,但是他们的确是认识它的。所以在某种程度上,你必须将其当成是合理且合法的。”

然而还有许多其它的游戏通过销售付费货币和道具赚钱。就像在《卑鄙的我:胶囊快跑》中购买代币而重新开始比赛并不能与在《海盗奇兵》中花费40美元购买Blackbeard的船只进行直接的比较,这也与在《Moshi Monsters Village》中加速建设计时器不同。但免费模式都是依赖于幻想经济去销售它们的推进器或道具—-每个例子中的IAP都是关于一定的宝石,代币,Rox等等。

Buckingham说道:“基于这些方法,存在一种全新的方法,而这也是一个致命的陷阱。或者至少会误导人们。因为我们所讨论的是虚拟货币,对于真钱的替代品。如果孩子们不能完全理解如何进行操作以及它的价值,我想这便是一个很大的问题。”

Buckingham对于那些6,7岁且“不清楚钱的价值或东西的成本”的孩子们进行了研究。

我们可以发现一个关于儿童对于成人经济世界的理解的研究。在20世纪50年代初Anselm Strauss和Karl Schuessler这两位先驱呈现了孩子们从4岁半到11岁半这一过程循序渐进的认知发展—-即从模糊地认为钱是用于购买东西到理解利润的概念。之后在1981年Anna Berti和Anna Bombi所进行的研究则专注于3至8岁的儿童,他们的研究告诉我们即使是这些样本中最年长的孩子也不能理解定量意义上的金钱(如“特定货币单位的”真正价值)。

在2000年R.S.Siegler和D.R.Thompson也展开了一项名为“低买,高卖:非正式经济理论的开发”的研究。这项研究检查了从6岁至10岁的孩子们对于经济理念的理解,并为了帮助理解将其划分成4个核心部分—-最小的孩子理解人们想要获得商品,而10岁的孩子理解人们追求利润,节约,竞争等理念。

还有一些后续研究,即使在不同研究中关于年龄和理解的划分是不同的,但是整体的证据弧线却是无可争议的。儿童对于经济理念的理解在他们到达青少年前是不断发展的;年纪越小,理解便越模糊。

Buckingham说道:“他们可能了解广告和市场营销,但却不了解他们所花费的钱。所以我认为存在一个基本原则:如果人们理解发生了什么,那么是否还存在欺骗的可能性?”

我们必须在虚拟货币环境中进行考虑—-这是“真”钱上一个抽象的层面。Lehdonvirta说道:“不管你是在说孩子还是其他消费者,交易都是发生在一个不熟悉的货币单位上,这让消费者更难将其与其它事物的价值进行比较。机会成本也变得更难评估。”

如果孩子们未能完全理解金钱,那么虚拟货币将增添他们的困惑,从而导致欺骗的可能性。

未来

小男孩拿着家里的平板电脑,便窝在了沙发上。他快速翻阅着屏幕并直接打开了基于IAP的《海岛奇兵》。但在游戏加载时,这位玩家已经被识别出是个孩子了,所以在他游戏过程中不会出现任何IAP或购买画面。

这是我所想象的场景,但却不一定是幻想。苹果的iPhone 5S是伴随着Touch ID(游戏邦注:手指识别服务)发行。现在以及未来的设备能够轻松识别玩游戏的家庭成员并自动隐藏IAP,然后在遇到成人手指时快速恢复。这样的措施将取代法律并让任何家长感到满足,但同时也意味着游戏将不能再面向儿童销售或推广IAP。

Nathan Ditum说道:“双方都是有责任的。家长必须判断游戏体验是否值得花钱,这是支付一种之后不会再向你要钱的游戏体验的真正价值。而关于游戏产业,我认为创造致力于培养孩子们对于需要不断花钱的东西的欲望是一种不道德的做法。”

在3月27日,苹果向那些执行了IAP的家长发送了一封电子邮件,突出了该公司的家长控制同时说明已经“为家长完善了控制,如此他们便能够更好地管理孩子们的购买或限制他们”,并会“在某种程度上”提供赔偿。

免费的儿童游戏呈现了一个全新的业务和道德十字路口,这里的目标市场包含了最年轻的也是最脆弱的社会成员。

我们未能追踪到独立应用的目标用户群体。缺少客观的外部数据(基于学术和社会研究)将会造成严重的后果。开发者和平台所有者并不想要谈到这点。

Jeffery说道:“如果你认为这些游戏是软件提供给儿童的内容的巅峰,你便大错特错。这里还存在一些关注点,即付费市场正不断衰退。但主要还是取决于独立开发者,只要他们不创造致力于骗孩子钱的产品便可。”

Shokrizade说道:“这并不像是我作为一个局外人在发牢骚。我是一个实实在在的局内人。我正效劳于这个产业中最知名的公司之一。我也不是在提一些空想的建议。我是真的在说一些能够带给包括苹果在内的公司帮助的建议。”

“现在,人们普遍带有的一种心态便是这些设备上的免费游戏都是骗人的。而现在最容易受骗的消费者便是年纪小的孩子们。如果不存在任何针对于这些消费群体的保护措施,这将酿成巨大的问题。”

(本文为游戏邦/gamerboom.com编译,拒绝任何不保留版权的转功,如需转载请联系:游戏邦)

SELLING CANDY TO BABIES

By Richard Stanton

Nathan Ditum has been a games journalist for a decade, and lives in England with his wife and family. When his son was 9 years old, Ditum gave the boy an iPod Touch. That’s when the trouble started.

“It was a free football game called Fantasy Manager that caused the problems,” Ditum says. “I was playing [real] football myself a day or two later, checked my phone afterward and saw an App Store receipt had come through for £23 ($38.50).”

As Ditum read the bill, another charge came through. And then another, for a total of close to $200.

“I freaked out, rang my wife straight away and she spoke to our son who said he hadn’t been doing anything.”

The United States Federal Trade Commission recently investigated Apple after hearing “at least tens of thousands of complaints” from parents whose children had made in-app purchases on the App Store. These IAPs are available within many games, are often associated with free-to-play business models and can be for anything from expansion packs to subscriptions to premium currencies.

These purchases can rapidly amount to budget-busting extremes and beyond. One child spent well over $6,000 on a game called Smurfs’ Village, the type of story that has led to the game industry coining the euphemism “bill shock.” The widespread attention IAPs have generated tends to focus on extremes like this and less on the much more common problem of smaller amounts charged to families like the Ditums.

“This one’s text went out of its way to hide that link, and so a nine year-old spent over a hundred pounds within a few minutes.”

“I went home and got my son to show me what he’d been doing,” Ditum says. “And basically within [Fantasy Manager] you needed a currency called ‘shields’ to buy [football] players — and it in no way made it clear that this was linked to real money. You know there’s normally that blue dialogue box saying do you really want to buy a hundred shields or whatever? This one’s text went out of its way to hide that link, and so a nine-year-old spent over a hundred pounds within a few minutes.”

After discovering what had happened, Ditum went further than most parents — as well as contacting Apple, he tracked down the developer behind Fantasy Manager at From the Bench. “I found out his email and contacted him to tell him how unhappy I was and made it clear to both him and Apple that what really bothered me was this issue around the password.”

What bothered Ditum was that neither he nor his wife had entered the device password — and there was no way his son could’ve known it. The family had multiple Apple devices, which was one possible cause, but no explanation was forthcoming about how these IAPs had gone through.

“Neither of them engaged with that,” says Ditum. “They just refunded the money.” And they refused to discuss the issue further.

Yet that wasn’t the end of it. After the fourth charge came through, Ditum’s bank put a hold on his account as a precaution, viewing the activity as suspicious.

“That’s a flag in itself, isn’t it?” Ditum says. “If IAPs can turn up on a system designed to spot credit card fraud, that suggests something’s not right.”

Child’s Play

“In order to be successful in freemium games,” says Bj?rn Jeffery, CEO and cofounder of children’s developer Toca Boca, “you have to build something that is very heavily gamified and with fictitious constraints, which you can then accelerate by spending more money.

“This is intrinsically different from trying to make something that children will love.”

Since 2010, Stockholm-based Toca Boca’s games have amassed over 50 million downloads and countless awards and five-star ratings. Toca Boca calls its critically acclaimed productions “toys” because they’re free of overtly gamey apparatus-like levels and progression systems.

Toca Band, for example, gives players a stage and multiple characters then lets them mix and match the stage setup to play a song in thousands of arrangements. Toca Boca’s games sell for an upfront cost with no in-app purchases and make what Jeffery calls a “healthy profit.” In terms of children’s app developers, this puts the studio in a vanishingly small minority.

“For Toca Boca, F2P was on the agenda before we even started,” Jeffery says. “We quickly identified [IAPs] as a pain point for a lot of parents, creating an insecurity — ‘What will happen when I give my kids this device?’ — and not really knowing. That was one of the things we wanted to change. Unfortunately, not a lot has changed.”

F2P business models are variations on making the consumer play the game first, then monetizing through advertising or, overwhelmingly, IAPs. The latter method of purchase is, as of December 2013, responsible for 92% of App Store revenue and 98% of Google Play revenue. And as these platforms make their way into more homes (55% of America’s adult population owns a smartphone, and 42% owns a tablet), F2P models are increasingly dominant in children’s games.

“The F2P space for kids is unfortunately a highly predatory one,” says Jeffery. “There are a lot of developers doing things they must know and feel are not the right things to do. It is predatory, and it is lucrative. We make six apps a year. Companies like TabTale make 200. It’s a machine, a freemium converting machine.”

How much?

IAPs account for an increasingly overwhelming proportion of mobile revenue. External app analytics platform Distimo’s 2013 report says that in January of 2013, 77 percent of overall App Store revenue came from IAPs; by November of 2013, that figure was 92 percent. IAPs on Google Play, as a percentage of total revenue over the same period, jumped from 89 percent to 98 percent. Games represent approximately two-thirds of these purchases, making gaming IAPs the biggest single source of revenue in apps — by a long distance. The App Store’s revenue for 2013 was $10 billion, so a conservative estimate of the value of the F2P games market — on iOS alone — is around $6 billion a year.

Moshi Monsters Village

“The bottom line is that it’s extremely difficult to build a successful kids’ mobile game with an upfront price,” says Michael Acton Smith OBE, CEO and creative director at Mind Candy. “The vast majority of games in the App Store are free with IAP.”

Moshi Monsters Village is Mind Candy’s first F2P app, released on Dec. 24, 2013; its second F2P, Moshi Karts, followed it in February. Moshi Monsters Village is a town-builder; you start with one monster and, over days and weeks, collect more and build a village for them to live in.

The game’s system is constructed around classic F2P principles: Players begin with a small quantity of premium currency, which they are immediately taught to use to speed up building times. There are countdown timers, an energy (“Gloop”) meter limiting certain activities, and huge jumps in construction costs. It is a design meant to compartmentalize and artificially slow the player’s progression so the player becomes tempted to buy a boost through IAP.

It is a game designed specifically for kids to play. It is also designed specifically to encourage players to spend money. These potentially conflicting goals are not lost on either Mind Candy or Apple.

As part of Apple’s iOS 7 release for its tablets and smartphones, Apple introduced a kids category to the App Store. It divides apps into three age ranges, demands compliance with the Children’s Online Privacy Protection Act and places restrictions on advertising and data collection. Apps placed into this section are, according to Apple, “suitable for children.”

The Kids category in iTunes is meticulously curated, well-organized and unfortunately doesn’t contain nearly as many apps as it should. There is no room here for F2P games like Nemo’s Reef or SpongeBob Moves In, city-building games that sell premium currencies, nor for infamous apps like My Little Pony: Friendship is Magic, which sells a pony costing roughly $70 worth of premium currency.

“Apple making a kids’ category with guidelines is a good first step,” Jeffery says. “But what’s happening unfortunately is that a lot of developers are not fitting within that category. They’re making kids’ products but not putting [them] in that category to avoid those constraints. I think that speaks for itself.”

“There’s no real agreement as to what constitutes a kids’ game,” says Jas Purewal, an interactive entertainment lawyer who works at the firm Osborne Clarke. “Angry Birds, Cut the Rope, Where’s My Water? — are they kids’ games? Cut the Rope is rated 7+ so it’s a pretty good bet that’s intended as a children’s game, but if you ask people you might get a variety of answers. On the other hand, is Mind Candy’s Moshi Monsters Village a kids’ game? Almost certainly yes. It just is.”

Yet Moshi Monsters Village is not in the App Store’s Kids section. Neither is one of the most successful children’s games released last year, a movie tie-in to Disney’s Frozen.

Candy Crush Saga is one of the most successful F2P games ever, and the scale of this can be seen in developer King’s recent IPO filing which shows that over the last three months of 2013 players spent $493 million in its mobile apps (78% of whom are playing Candy Crush Saga). Disney’s Frozen Free Fall, a tie-in to the children’s movie, copies the formula of Candy Crush Saga thoroughly, to the extent of introducing the same match-three mechanics (such as T and L shapes) at the same pace, using purchasable power-ups for the same functions, and using the same progression structure, albeit with fewer levels. Disney Interactive is a division of the largest media conglomerate in the world, and it made an F2P tie-in to the biggest children’s movie release of 2013 based on a design proven to successfully monetize its audience in a big way. Frozen Free Fall is not listed in Apple’s kids’ category.

In Moshi Monsters Village, the premium currency, called “Rox,” can be used to skip timers or exchanged for other in-game currency. It is impossible to miss that the Rox menu icon is highlighted over and above its surroundings with an eye-catching, shiny effect that no other icon shares. Mind Candy claims this works differently for users under the age of 13, although it seems to work for players registered as young as 7.

“We’ve tested the product extensively and have had no complaints about it,” Smith says. “In fact our users are very happy to pay for additional currency, and our feedback has been very positive. The users should be the judge of the design decisions.

“If IAP isn’t allowed for kids’ products then the economics are such that very few developers will … be able to make amazing entertainment for kids on mobile devices. That’s a very sad scenario for all concerned.”

Legislation and self-regulation

F2P first rose to mass-market prominence in Asia in the late 1990s, particularly in China and South Korea. Many of the current questions facing Western developers in the F2P market have therefore already been addressed by or for Eastern developers.

Legislation was passed in South Korea in 2010 and among its specifics are that school-age children are barred from playing 19 popular MMOGs like MapleStory or Mabinogi between 12 a.m. and 8 a.m. — this legislation is referred to as the Shutdown Law, or the Cinderella Law.

“In South Korea [children's F2P games] have been a much bigger issue and they take it very seriously,” says Ramin Shokrizade, the full-time economist for the World of Tanks developer, Wargaming. “They have the equivalent of a social security number that you have to input before playing a game so they know how old you are, and they put restrictions on how you can be sold to, how much you can spend if you’re a minor, even how much you can play. I think that’s pretty cool and ahead of everyone else.”

In this instance the South Korean government was acting after several years of consultation and research into the issues; but legislation is not always born of considered reflection. “With kompu gacha [in Japan] the way it happened was that moral panic took hold of the media,” says Dr. Vili Lehdonvirta, an economic sociologist specializing in virtual economies, a research fellow at the University of Oxford’s Internet Institute as well as a virtual economy consultant for companies including Habbo and Mojang.

The kompu gacha mechanic is basically a gambling mechanic, using in-game slot machines to distribute various items that have to be collected in sets to acquire “rare” items. The Japanese newspaper, Yomiuri Shimbun, reported, among many other examples, that one user had spent in excess of $50,000 chasing particular virtual items.

“So regulators needed to be seen … doing something and eventually declared this illegal,” Lehdonvirta says. “Suddenly these companies have very invasive government regulation that restricts what they can do. If they’d been smarter — there was a lot of discussion and public indignation about gacha, so they could have self-regulated and possibly avoided this by putting softer self-control in place.”

The potential for a Western moral panic around F2P games aimed at children is obvious. “I don’t know what will happen [with IAPs in children's games],” Lehdonvirta says. “But I think it would be very smart of the industry to do some self-regulation.”

Self-regulation, however, requires first acknowledging a problem. Disney and Nickelodeon, both of which develop a wide range of children’s apps including multiple F2P titles with premium currencies, declined to comment for this article.

“I don’t think companies like Disney will take any action without regulators making them,” Shokrizade says. “I’ve been putting pressure on Disney and I’ve not been alone in that regard. Especially considering they have some of the most offensive products, and I’ve let them know this.”

In October of 2013, Shokrizade spoke to the International Consumer Protection and Enforcement Network in Panama and demonstrated the F2P mechanics of Marvel Super Hero Squad Online, a browser game, in front of Disney representatives. He’s yet to see any action on the issue.

“I don’t think companies like Disney will take any action without regulators making them.”

“I’m absolutely certain Disney will not improve the quality of their products without being forced to,” Shokrizade says.

Many companies argue that, in such a fast-moving field as mobile games, rushing to judgement will be counterproductive. The European Commission, in the last few weeks, has nevertheless announced that it will hold meetings with the industry to discuss four issues around IAPs, one of which is “direct exhortations to children to buy items.” Further action is possible, but the European Commission’s initial attitude will be to try and work within the existing legal framework.

“All of the laws exist already,” says Purewal. “Consumer protection, data privacy, IP laws, but their application to an industry that is very young is still uncertain. The starting point is always what existing laws do we have, and how can a regulator try to use that existing framework to achieve the outcome it wants — in this case the protection of consumers.”

The biggest stakeholders in the IAP question are easy to identify — the platform holders. If appropriate legislation already exists, and developers will not voluntarily limit their own activities, then Shokrizade believes the gateways themselves, places like Apple’s App Store, are where interventions must be made.

“The platform holders are the only way this can be solved,” Shokrizade says. “If there are 40,000 new apps coming out every year there’s no way you can go in and evaluate each app to decide if it’s meeting regulatory standards; there’s just no way. But hold the platform holders responsible and then it’s gonna happen. Especially if the platform holder’s getting 30 percent, then they have a vested interest in making sure it happens.”

And that leads back to the App Store’s Kids section and how games like Moshi Monsters Village are avoiding it.

A recent settlement between Apple and the US Federal Trade Commission led to Apple refunding up to $32.5 million to parents whose children had unintentionally spent money on IAPs. But the terms of this deal, and the specific apps it concerns, are not as straightforward as they appear.

“There was some strange language in the FTC complaint that I thought let Apple completely off the hook,” says Shokrizade. “What was bothersome was how it talked about games ‘suitable for children.’ There are very few games that are ‘suitable for children.’ There are lots of games played by children. And that’s where the vast majority of spending and possibly misspending is happening.”

The settlement figure for refunds was based on Apple’s own estimate of the number of people affected. But Shokrizade believes Apple is not an objective source of information on those figures.

“EEDAR is an objective source,” says Shokrizade. And EEDAR found recently that, of parents who play video games on their devices, 80 percent of their children also play mobile games on their devices. Of those children, 22 percent make unauthorized in-app purchases, and when they do, they tend to spend much more than an adult would.

“The difference between the 0.13 percent unauthorised purchase rate [that Apple suggests] and 22 percent is the difference between the $32.5 million Apple spent and the $5.3 billion that they maybe should’ve spent.”

Grown-Ups

Although this article concerns the use of F2P in children’s games, questions over certain business models’ techniques extend to the adult audience. The top 5 percent of spenders in the mobile market are categorized as “whales,” and games like Candy Crush Saga and Clash of Clans are built to take maximum advantage of their spending habits.

The question then becomes, with the exception of children, should these users be protected from themselves? Consider the gambling industry for comparison, which is heavily regulated due to a high enough proportion of the population being at risk of addiction. It is an open question as to whether certain F2P techniques are coercive, and if they are, what should be done about them. The industry has thus far been able to hide behind commercial confidentiality, but it is resisting investigation of an area that could have enormous ethical and financial consequences.

Candy from babies

Games like Moshi Monsters Village are built on a widely used F2P template. Whether the genre is city building or pet collection or racing, F2P games often offer little more than a proven business model with new visuals draped on top. The reason for this is data-driven design.

Data collection in the interactive entertainment industry is widespread; in some games every single action is registered, as well as the time spent on particular screens or sections. Every gaming company in this space has a “business intelligence unit” dedicated to finding out how people play its games and what can be done to fine-tune the design and, thereby, the profits.

“They want to collect as much data as they can about everyone using their products,” says Shokrizade. “Then if you have the right people you can use that to change pricing or maybe look at weaknesses in the game — like if everyone’s quitting after 30 minutes, why? There are a lot of constructive uses for this information and then there are some less constructive uses.”

Less constructive uses are the identification of especially acute bottlenecks — points in the game that squeeze and tempt that crucial first investment, perhaps with a difficulty spike or a locked door, after which players are much more likely to spend money again. Former Zynga executive Roger Dickey memorably described these moments as causing “fun pain.”

Such numbers-led design, combined with an increasingly sophisticated understanding of feedback loops, means these games have moved past observing player behavior into attempting to shape it. Are children playing these games, or is it the other way around?

“The term psychological manipulation is a bit alarmist,” says Professor David Buckingham, an expert on children’s interactions with electronic media who has authored or edited over 25 books on the subject. “You could argue every book we read or movie we see engages in psychological manipulation.

“People who have experience of games learn how they work and how the systems operate. Manipulation implies people are being molded, that they’re passive dupes of some all-powerful system, and I just don’t buy that.”

Professor Buckingham recently led an independent assessment for the UK government called “The Impact of the Commercial World on Children’s Wellbeing.” He argues that a focus with the F2P business model should be on what children do and do not understand. Many F2P games, for example, rely on ads rather than IAPs to make money — but that is intrusive and ugly, and children think so too.

“With conventional advertising, a lot of evidence makes it pretty clear that young kids understand what advertising is and what it’s trying to do,” Buckingham says. “They may accept it or not, but they understand it. So on some level you have to see it as reasonable and legitimate.”

Many others, however, make money by selling premium currencies and consumable items. It might seem like buying tokens in Despicable Me: Minion Rush to restart races is not a straight comparison with buying Blackbeard’s ship for around $40 in Playmobil Pirates, which is not the same as speeding up a construction timer in Moshi Monsters Village. But F2P models all share a reliance on fantasy economies to sell their boosts or items — the IAPs in each case are for quantities of gems, tokens, Rox, and so on.

“With these methods there’s a new issue and that is deception,” Buckingham says. “Or at least people being very misled. Because what we’re talking about is virtual currency, a surrogate for real money, and if children don’t fully understand how that operates and what it’s worth — then I think there’s a problem.”

Buckingham has done research with children who are as young as six and seven years old and who “clearly have a very hazy idea about the value of money or what things cost.”

There is a significant body of research into children’s understanding of the adult economic world. The pioneering work of Anselm Strauss and Karl Schuessler in the early 1950s showed gradual cognitive development in children from ages 4 1/2 to 11 1/2 — from a vague idea that money is used to buy things to an understanding of the concept of profit. Later work by Anna Berti and Anna Bombi in 1981 built on this and, focusing on a younger age group of 3 to 8 years, showed that even the eldest of the sample didn’t understand money in a quantitative sense (i.e., the “true value” of a given monetary unit).

More recently in 2000 R.S. Siegler and D.R. Thompson undertook a study, Buy Low, Sell High: The Development of an Informal Theory of Economics. This examines children’s understanding of economic concepts from the ages of 6 through 10, and by dividing them into four core areas of understanding shows a clear development — the youngest children understand that people desire goods, and not much else, while by age 10 there is an understanding of profit-seeking, saving and competition.

There is much subsequent research but, even if the exact division of ages and understanding differs from study to study, the overall arc of the evidence is indisputable. Children’s understanding of economic concepts develops gradually until they are teenagers; the younger they are, the poorer it is.

“They may understand the advertising and marketing side, but not the money they’re spending,” Buckingham says. “So I think there’s a fundamental principle: Do people understand what’s happening, and is there a possibility of deception?”

This must be considered in the context of virtual currency — a layer of abstraction atop “real” money. “Whether you’re speaking of children or any other consumer,” says Lehdonvirta, “the idea that transactions take place in an unfamiliar unit of currency makes it harder to compare the value in relation to other things. The opportunity cost becomes harder to evaluate.”

If children do not fully understand money, and virtual currencies add even more confusion to the mix, then that possibility of deception exists.

The future

A young boy picks up the family tablet and slumps into the couch. He flicks through screens and straight to the IAP-packed Boom Beach. But as the game loads, this player has already been identified as a child, so not a single IAP or purchase screen appears during his playtime.

This is an imagined scenario, but it’s not necessarily fantasy. Apple’s iPhone 5S launched with Touch ID, a fingerprint recognition service. Current and future devices could therefore easily identify when young family members are playing and automatically hide or disable IAPs, then restore them just as easily for adult fingers. Such a measure would preempt legislation and satisfy any parent, but would also mean games could no longer sell or advertise IAPs to children.

“On both sides there’s a responsibility,” Nathan Ditum says. “Parents have to recognize that experiences are worth paying for, and there’s real value in paying for an experience that isn’t going to ask you for more money afterward. And on the part of the industry I think it’s unethical to create children’s games designed to foster this desire for things with potentially infinite costs.”

On March 27 Apple sent out an email to customers who had made IAPs, highlighting the company’s parental controls and saying that it has “improved controls for parents so they can better manage their children’s purchases, or restrict them entirely,” and “in some cases” will offer refunds.

F2P children’s games represent a new intersection of business and ethics worth an enormous amount of money, one in which the target market is comprised of the youngest and most vulnerable members of society.

The demographics for individual apps are either untracked or unknown. The absence of objective external data, in the form of academic and social research, is crippling. Developers and platform holders simply don’t want to talk about it.

“If you think these games are the peak of what software can offer children then you are sadly mistaken,” Jeffery says. “There are concerns … that the paid market is declining. But it’s up to individual developers not to make products that are intentionally designed to cheat children out of money. That’s just awful.”

“It’s not like I’m an outsider complaining,” Shokrizade says. “I’m an insider. I work for one of the top companies in the industry. I’m not giving advice that’s fantastical. I’m giving advice that I think would help the income of these companies, including Apple.

“Right now F2P on [these devices] is dominated by a mindset where it’s all about tricking the consumer. And right now the most gullible consumers available are small children, or any children. And as long as there’s no protection for that consumer group, it’s the wild, Wild West.”(source:polygon)

.jpg)

.jpg)

闽公网安备35020302001549号

闽公网安备35020302001549号