阐述富有道德性的F2P游戏设计原则

作者:Greg Costikyan

游戏行业元老和前Playdom高级游戏设计师Greg Costikyan在此文讲述了免费模式(F2P)道德性如何影响游戏的成功。

广告行业发展过程中的一位重要人物David Ogilvy曾说过:“消费者并不是傻子,她是你妻子。”他用此话回应了自己对讽刺性和操纵性广告的看法。但在F2P游戏领域中,多数人都为这种将消费者视为傻瓜的态度而愧疚。更糟糕的是,甚至有人将他们视为可通过操纵性和不道德的商业手段所宰割的羔羊。或者换句话说,我们通常会为了短期收益而牺牲长期留存率,为了提升短期的盈利指标而冒险惹恼玩家。

我们的F2P行业从本质和文化上看,都过于强调短期利益。初创公司急于推出关口,立即兑现收益,基本上没有长期的目标,或者仅过了三五年就委身于更大的公司或者进行IPO。在此我不想列出公司名称,但我知道至少有一家F2P游戏公司有意最大化一款游戏的短期收益,也完全清楚这会危及用户基础,导致游戏迅速衰落,因为他们已经趋于全面被收购状态,打算让本季度收益财报更好看,从而卖个好价钱。

我们的指标很容易看出短期发生情况,却更难确定其中的长期影响,如果你调整了游戏,进行了A/B测试,从指标中看到你的ARPDAU增加了,呈现了很棒的趋势,并因收益增加而结束了测试。

但这些指标没有告诉你,你的所做所为已经惹恼了玩家,数周或数月之后,这只会增加你的用户流失率,如果你看到流失率增加,很可能是过去数周和数月进行了调整,但此时就很难追踪究竟是哪个调整导致的结果。

当然,我们的行业有许多善于思考和有道德的人,但毫无疑问这一行也有许多相信可以靠一些心理操纵伎俩来诱使玩家付费,并且认为这是一种优秀而合理的商业手段之人。

因此,我们看到在F2P市场中:F2P游戏通常的生命周期不会超过一年。它们发展,吸金过程中,用户数量却开始下降,在某些时候运营者会发现其终身价值(LTV)却远低于用户获取成本(COA),突然停止营销活动,游戏就不知不觉中进入一个死循环中。原有用户流失后,少数新用户进入,游戏之后也很快面临关闭的境地。

对于像我这种已有数十年网络游戏背景的人来说,这真是令人惊讶。在F2P崛起之前,网络游戏具有永久运营的潜力,事实上,我们很难真正让一款网络游戏毙命。我以3个例子来说明:

《Hundred Years War》(hyw.com)是出现于70年代晚期的电脑邮件式游戏,后来成了旧广告GEnie网络上的一款网络游戏,至今仍在开放网络运行。

《Gemstone》(www.play.net/gs4/)最初是GEnie平台上的一款付费MUD,至今仍存在(并为其开发商Simutronics持续创收),它现在是一款拥有铁杆粉丝的文本MMO游戏。

《Ultima Online》(www.uo.com)发布于1997年并且持续至今,拥有成千上万玩家,现在是一款次世代领域的复古2D MMO游戏。

再看看发布于1996年并且曾被运营者两次关闭的《Meridian 59》 (www.meridian59.com)——今天仍然在世,成了被粉丝所拥护的免费游戏。

你可能会说这些游戏的商业条件与F2P市场截然不同,我们不可能长期维持F2P游戏的运营,但你错了。《FarmVille》就是一个杰出的典型,它发布4年后,至今仍然拥有庞大的用户群体,在Zynga总收益中仍然占比16%,尽管Zynga后来又推出了《FarmVille 2》。

在去年的GDC大会上,Mike Perry发表了“为何《FarmVille》不会亡”的演讲,我和Perry都认为它没有理由无法延续数年,原因很简单:现在它正努力培养用户留存率。

Facebook现在已经是一个成熟的市场,Facebook游戏仍有许多创收空间,但这已经不是一个发展中的市场。手机F2P市场发展势头正猛,但预计再过两三年,它也会趋于成熟与饱和。成熟的市场要求的是独特的想法:淘金热可能会让快速和短视者受益,但在成熟的市场中,能够建立用户忠诚度的公司才是赢家。因此,开发者除了尊重玩家之外别无选择。

那么该如何进行有道德的F2P游戏设计?答案很明显:尊重你的用户。其他一切都要遵从这个简单的原则。

这个变化多端的市场无疑令那些已经习惯于过去一两年可行的模式的许多人胆战心惊,但我们应该欢迎这些变化。要考虑这个问题:你是愿意为一家拥有许多忠实粉丝的公司效力,还是一家将游戏视为一次性的垃圾,将玩家视为宰割对象的公司卖命呢?

尊重

我知道,有时候要尊重玩家真的很难,尤其是在你查看针对目标群体的用户测试,看到他们究竟有多无知的时候。或者看到你的首个用户体验参数,看到玩家在某个看似极为简单的任务上失手的情况之时。尤其是在休闲市场,你所有的玩家都很“无能”,你在设计游戏时应铭记这一点,但无论他们有多无能,仍然需要得到尊重。“你所有的用户都很无能”与“尊重你的玩家”这两种说法看似互有冲突,但你要同时抓好这两个原则:你必须同时制作极为简单的UI以及尊重他人的盈利系统。

制定长期计划

正如我之前所言,我们很难处理一项变化对玩法的长期影响。但事实上,常识和直觉会让你受益匪浅,迫使玩家向好友发送垃圾信息或者花钱的门槛今天可能会让你收到一点钱,但傻子都知道明天玩家就不会再来了。

《Pioneer Trail》的失败不是没有原因的,它拔高了垃圾信息门槛,玩家迅速对此生厌。

还有其他方法吗?

首先,不要将变化视为影响你短期指票的因素,而是视它们视为提升玩法的机会。在此我将以《Dragons of Atlantis》作为反例进行说明,如果你仔细观察,就会发现原设计师打算让游戏培养玩家的战略和阵地战意识,但战斗系统太残酷了所以就没有实现这一目的。你永远不会将军队留在前哨,因为那样就会让他们不堪一击。你几乎永远也保卫不了自己的基础(你将自己的军队设置为隐藏状态)因为战斗总会令其中一方彻底毁灭,而重建军队却是一项冗长而令人疲劳的任务。在游戏刚发布时就是这种情况,尽管Kabam做了多次更新,他们还是没有修复这个糟糕的战斗系统——我认为有可能是这款游戏已经够受欢迎了,所以其制作人被迫关注那些能够提升收益的调整。

如果他们能够关注玩家体验,我认为他们就会发现因为一不留神就让自己一方溃不成军真是一个令人恼火的时刻,如果能够修改这一战斗设计,重现设计师的本意,也许就有可能制作出更能长久留存玩家的游戏。Perry曾透露《FarmVille》持续成功的一个原因就在于其团队持续添加令玩家惊喜的新内容和功能。

我并不是说你永远不要进行有利于提升收益的调整,而是说你应该先让游戏从设计角度来看得到了优化。任何优秀的在线团队都应该包含一名游戏设计师和一名玩家顾问,以及一名作为盈利顾问的制作经理人——以及一名决定应该如何分配开发资源,并作为这两者调解人的制作人。

惊讶与快乐

你玩游戏是因为它们令你吃惊和快乐——好游戏基本如此。我们仍然听到发布F2P游戏的正确方法就是“创造最小可行性的产品”,即发布游戏,如果它获得关注,就继续投入优化——这里的“优化”意味着你需要A/B测试功能。更直接地说,这种方法可以描述为“抛出粪便并进行A/B测试,直到它不发臭为止”。

但这种方法并不可行,如果没有一个过硬的核心游戏,无论多少调整都无济于事。而构成“最小可行产品”的要素则像游戏开发的其他方面一样,其质量要随时间发展而逐渐上升,在Facebook游戏早期甚为成功的纯HTML5社交网络RPG现在永远不会获得关注了,因为我们现在对网页游戏的要求更高了。

更重要的是,在F2P游戏中,市场中的华文不是“你只能发布一次”。数据显示游戏的首批玩家盈利性比后来者更高;当玩家流失的时候,他们就极不可能再回头了。你可不想发布“最小可行产品”,你想发布惊人的产品,因为这样才有希望获得庞大的用户群体,实现长期成功。当然,你可以先针对某地区市场的小部分用户进行短期测试,并在全面发布之前获取相关参数,并降低你的营销投入,但你只有在游戏润色之后才能全面发布产品。

你的玩家并非A/B测试的小白鼠,他们是人类,如果你身处娱乐行业,那就有责任一开始就为他们提供高质量的娱乐内容。

我们应该放弃初创团队的思维,额外投入20%的精力创造优质的游戏。

不要滥发垃圾信息

在F2P领域,我们总能听到许多关于“K因子”的讨论。实际上,这是一个借用流行病学的术语。K因子是指健康的人被一名病人传染的数量,在与传染病斗争的过程中,你得通过将病人隔离在家,戴上面罩、接受治疗等措施将K因子降到最小。在游戏中,我们用它来指代每名已获取玩家所带来的新玩家数量,我们需要增加K因子。Facebook游戏曾一度出现非常可观的K因子,即新游戏的用户量可以飞速增长——这也意味着游戏开发者为实现自己的利益而让玩家发送更多信息,创造更多动态和涂鸦墙内容,因为他们的曝光度而吸引了更多玩家。

所以每款游戏都鼓励你每回都发布病毒信息,在某些情况下甚至强迫你去做——因此许多城建游戏中含有“人员安置”机制:为了启动一个新建筑 ,你需要6名好友来安置其中成员,所以今天就要邀请他们。

在这种人员安置机制的条件变得很麻烦(有时要求高达14名成员)时,我就退出了游戏,我相信并非只有我一个人受不了。它们确实培养玩家发信息的习惯,但也损害了游戏的长期留存率。那么我们还能做什么计划呢?

这里举个欺诈性做法的例子:多数游戏会让你在首次用户体验时邀请好友参与。但许多游戏并不允许你关闭这个邀请的弹出对话框。游戏中只有一个“邀请”按钮。用户只能被迫点击按钮——不然就退出游戏。此时就会弹出好友列表对话框,你可以关闭它,在不发送邀请的情况下返回游戏,但这等于是告诉玩家“我们将你视为待宰的羔羊,并想让你发送病毒性消息。”这根本就是与尊重玩家背道相驰。

A/B测试含有和不含关闭按钮的邀请对话框,我保证你会发现两种情况:第一,如果没有关闭按钮,会有更多玩家发送好友邀请。第二——你会发现在自己的游戏中,更多玩家在此节点上退出,甚至有些玩家会说“去你的,我才不干。”换句话说,你得权衡保留这些玩家,以及获取更多其他用户这两个选择。很难说哪一者更有长期利益,但我们不难说“你就是不尊重这些玩家”,所以这是一个大忌。

在手机F2P游戏中,发送信息功能的问题更多。没错,玩家很容易向自己手机通讯录中的人发送信息,如果他们通过Facebook Connect登录,也可以向Facebook好友发磅。但手机并非社交网络,在手机上发送这种信息也显得极不自然。没有多少玩家会这么做,除非你逼他们——而胁迫他们就是不道德的行为。

现实就是现在的K因子已经很小了,很大部分是因为Facebook削弱了病毒渠道(发送信息也从来不是手机平台的主要玩家来源)。你将无法再看到来自游戏的动态或涂鸦墙,除了那些你已经在玩的游戏相关信息。通常情况下,不到3%的用户是来自病毒渠道,那么你认为值得为这么少的用户去骚扰玩家吗?

病毒传播仍是玩家留存的一个有用功能,通过好友而获得游戏信息的玩家更可能重返游戏,当然,这正中你下怀。但最好是通过积极的信息,例如“免费礼物”而非消极的游戏门槛来培养玩家的游戏习惯。

如果你想培养玩家发送信息的习惯,不要采用强迫手段,而要让它与游戏具有内在联系,与游戏设计浑然一体。例如,在《Knighthood》这款游戏(目前已经不存在)的游戏中,你要扮演一个中世纪的贵族。如果你邀请好友,他们也加入了游戏,那么他们就会成为你的奴仆——你能收到他们每天生成的一小部分资源。这与游戏核心想象十分匹配,也提供了玩家发送邀请的强烈风餐露宿同,从玩法角度来看也极具实用性,因为你想让自己的好友开心,以免他们离开投向另一个主人的怀抱,因此也有帮助他们的强烈动机。换句话说,这是优秀的社交工程和游戏设计。

不要再问“Zynga会怎么做”了。我们知道Zynga会怎么做,但对他们来说结果并不理想。我们应该问的是“我该如何让玩家想发送信息?我该如何为他们创造积极的体验?我该如何将信息功能嵌入游戏核心,让它成为自然而自发的行为?”

为内容付费永远是可取的

《英雄联盟》是目前市场上最成功的F2P游戏之一。与多数F2P游戏一样,它有一系列不同的盈收点,但其中最具盈利性的却是champion。这是一款DOTA风格的游戏,champion是可玩角色,每个都有自身优势和弱点,每个都能带来不同体验,他们与其他角色会以有趣的方式结合,总能让玩家产生解琐更多角色的渴望。

虽然玩家可以通过刷任务来购买角色,但这需要极冗长的时间才有可能解琐所有角色(以及解琐定制化champion的符文——仅限使用软货币购买)。因此,玩家有极强的游戏动机,至少有许多玩家时常如此。

这是一个极为诚恳而合理的系统,我知道自己获得了什么,也能看到其中的价值。更多的是,如果我满足以只玩一个或一系列champion,我就可以不花钱获得所有champion的符文。只有在我对游戏非常依赖的时候,我才可能为之付费;而如果我真的那么喜欢游戏,我就会觉得自己花钱买到了价值(注:我并不是赞扬《英雄联盟》的盈利系统是完全道德的,符文的销售表单让我厌恶,但销售champion却是相当合理的)。

另一个例子,《Plague,Inc》提供了7种可玩的病毒类型(在Anroid版本中免费,在iOS则是付费),玩家可以在游戏过程中解琐。没耐心的玩家可以付费早早解琐,游戏还提供了3种附加内容包供玩家购买,其中两种提供了截然不同于最初7种病毒的可解琐病毒,另一者提供了14个额外场景。这是一种诚实的交易,我很高兴地全部购买了这3个内容包,因为我非常喜欢这款游戏,也想为其开发者做一点贡献。

当然,制作内容需要开发时间和资金,这并不像易消耗品或门阀一样极具盈利性。它可能无法成为你唯一的盈利点,但比起一次性绕过计时器的道具,玩家更愿意购买这些内容。我如果你提供付费内容,将会看到更高的付费玩家比例(例每付费玩家收益不一定会更高)。

获取进步,而非付费取胜

不久之前,Wargaming.net宣布移除《坦克世界》中的“付费取胜”元素。这可以说是一个明智之举,毕竟付费取胜是导致玩家忿而离去的一大关键因素,玩家离开是因为觉得被游戏唬弄了。如果你是一名免费玩家,或者手头拮据者,在游戏中就会感受到其中深深的恶意——那些玩家只是因为有钱就可以打败你。

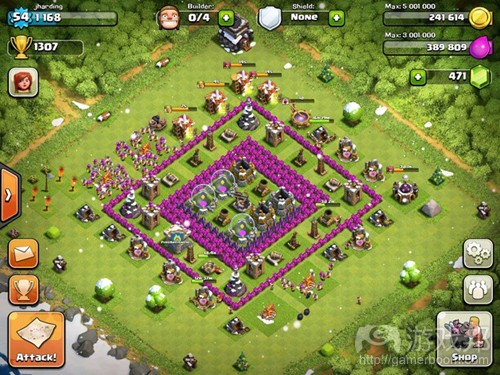

《Clash of Clans》以一种明智的方式处理了这个问题,同许多游戏一样,你可以通过付费绕过计时器而加快进度,但涉及战斗时,你却只能和实力不相上下(取决于城镇中心水平)的玩家过招。如果我有一个6级的城镇中心,我就会与水平与我相当的玩家战斗——他们是通过刷任务还是付费升级与此无关,总之这还会是一场公平的战斗。付费会让你更快进步,但不会让你在战斗中获得优势。

显示价值

有个曾玩过《CityVille》的朋友告诉我“我花了50美元——这钱就这么没了。”换句话说,他喜欢这款游戏,也愿意为之掏钱——但过后就后悔了。他并不觉得自己花钱获得了价值,不久之后他就退出游戏了。

《Clash of Clans》是为数不多能够让我心甘情愿掏钱的游戏之一。它限制了你一次可建造的建筑数量。你一开始建造一栋小屋,并在首次用户体验中用硬货币购买了另一栋。你可以马上看到价值,更多小屋意味着你在持续、长期地加速前进。额外小屋需要花费硬货币,你可以通过完成任务、刷任务而赢得硬货币。有趣的是,这些任务奖励足够你再通过刷任务建造第三和第四个小屋。但花上10美元,你就可以立即购买第三个小屋,并且还有剩余的硬货币,再刷上几天任务就可以买到第四个小屋。从F2P标准来看,这一点相当合理。我喜欢这款游戏,也愿意为之付费(花钱绕过计时器,但我不是高消费用户,所以不会在其中挥霍)。

我很欣赏游戏给予玩家选择:即我可以选择刷任务。这感觉像是一种公正而诚实的交易。有趣的是,有款与之相似的游戏《Backyard Monsters: Unleashed》却是让你掏钱购买第3个建筑,不允许你通过刷任务获得。我很想知道这种做法究竟是更好还是更差。它仍然是个可靠的交易,但《Clash of Clans》允许玩家刷任务这一点会让我更喜欢游戏。Supercell知道如何盈利,但却不动声色地使用了调控措施。(至少在更早的游戏中,黑暗炼金药的低生产率为玩家提供了另一个强烈的购买动机)

与之相似,《英雄联盟》每周都会让玩家免费玩一些champion,以便玩家接触不同的champion,了解他们的优势和弱点。玩家显然会喜欢这种试玩体验。这无疑就会提升额外销量,当champion不再免费时,喜欢这些champion玩法风格的玩家就可以花钱购买。换句话说就是在你购买之前试玩,但使用的却是能够让玩家觉得积极而无可非议的方法。

刷任务可取,硬门槛不可取

许多人谴责F2P游戏中的刷任务机制,但这并非这种商业模式的特点,它源自几乎所有F2P游戏都有的“游戏永无止境”这种类似MMO游戏的特点。也就是说,它们没有尽头,也没有赢家输家之分。在一款永无止境的游戏中,你需要尽量拉长玩法,因为你得限制内容,即使是在最佳情况下,你的玩家消耗内容的速度也会超过你的预期。这正是为何计时器会延长游戏时间,为何《魔兽世界》中的升级需要通过mob战斗刷任务的原因。

刷任务从游戏设计角度来看并不是理想选择,但却是让游戏永无止境的必需品。

让玩家花钱来加速或绕过刷任务是可行的选择,而不付费就不让加速或者疯狂提高加速的难度,则是令人难以接受的做法。例如,在《Candy Crush Saga》有些关卡似乎就是有意设计成让玩家需要经过成百上千次尝试才能过关,除非你花钱购买额外的行动或能量提升道具。

有趣的是,Jing似乎随着时间发展而削弱了这种关卡。我毫不怀疑他们回应了玩家的抱怨,并且还A/B测试了这些调整。所以我认为我们可以用更柔和的方式提升盈利杠杆,成功增加他们的长期用户价值,与其让他们忿而退出游戏,不如庞寄希望于让他们将来实现更好的盈利性。

当然“疯狂的难度”是一个模糊的短语,其要点在于你已经向玩家承诺他们可以在不花钱的情况下玩游戏,刷任务,如果他们做出了这种选择,你就要信守承诺,不要让他们觉得“你只有一点点进步的可能”。

不要使用诱导转向法

《Marvel Avengers Alliance》每月都会发布“spec ops”。spec ops是一系列串联的战斗(以一个故事轴相联系在一起),在一定时间内完成这些系列的玩家(通常需要几周时间)可以免费获得一个新的可玩超级英雄。

但是,spec ops中的每场战斗都需要支出一定的货币(游戏邦注:这些货币只有在spec ops的期限内有效,在此将其称为“不稳定的ISO”)。每次你展开系列中的一场战斗时,你都要支出一定的货币。玩家一开始会有一定量的货币,但这些货币并不足以完成整个系列。

玩家可以相互赠送不稳定的ISO,但玩家每天可收到他人赠送的量是限定的,并且不稳定的ISO在战斗过程中也会成为掉落道具奖励。简而言之,开发者可以通过调整“每日可接收量”参数,以及战斗中的掉落率来限制玩家可以赢取的不稳定ISO数量。

这是spec op过程中的立即奖励,在任务序列中的某个节点,玩家还可以得到稀有的武器奖励,或者少量硬货币,或者其他某件东西。游戏中的玩家喜欢spec ops,因为它们提供了新颖而定期的内容,在这些序列的末尾有可口的奖励,即使他们无法完成,也可以获得即时奖励。

毫无疑问,玩家可以花真钱购买不稳定的ISO。因为spec op所奖励的超级英雄之后会出现在硬货币购买选项中,所以你通过购买限量的不稳定ISO,有可能以更少的直接购买价格得到这个超级英雄。

这种系统有道德吗?我认为这要看情况。如果游戏参数经过调整,在最理想的游戏情况下(最大的日常不稳定ISO礼物接收量,在战斗中耗损少,花时间刷任务),玩家就可以完成这些序列,那么这在我看来就是有道德的:你给予玩家更多内容,非付费玩家仍可成功,只是他们要花点精力。

如果,这些参数调整后让玩家根本无关在不付费的情况下完成序列,那么它在我看来就是不道德的。这是一种诱导转向法,就好像Lucy从Charlie Brown手中夺走足球。你是在冒充提供奖励,让玩家觉得他们可以通过刷任务实现目标,但却并不给他们机会。玩家最终会意识到这一点——你就会因此而失去这些玩家。

与玩家交友和支持玩家

我们应该重新掌握客服和关系管理的艺术。MMO开发者深谙此道,他们知道论坛的重要性,粉丝是游戏的传播大使,当更新内容出问题时论坛上的言论可能会出现警告标志,有时候你的一些最佳想法可能是玩家首创。没错,这种信息是道听途说的,你的参数才是硬数据,玩家有时候真的不知道自己需要什么,玩家通常会误解问题(游戏邦注:例如,他们会说某事“太困难”了,而实际上它是太无聊了);通常情况下你无法如他们所愿,因为市场条件不允许。当然你可以继续分析你的指标。

在F2P领域,客服却被视为一种沉没成本,即易被忽视或最小化的成本。许多游戏出现问题时,玩家却总是难以找到一个提供帮助的人。即使该公司具有客服部门,也通常与开发团队相隔绝,客服仅向开发者反馈一小部分内容,而任何来自开发团队的更新信息几乎都无法被玩家所知晚。这并不能培养一个社区。

客服并非沉没成本,客服是留存你可能会失去的玩家的机会——而考虑到你获取玩家所投入的成本,留存玩家就显得颇具价值。

让玩家设置上限

F2P市场的一个现状就是多数游戏是依造鲸鱼玩家为生,即一小部分高消费用户。如果你的鲸鱼玩家是迪拜王子或科技大鳄,那么这就不存在什么道德问题了。但如果住在贫民窟的人也在游戏中投入自己所无法承受的5000美元,那就真是个问题了。

为什么不更道德一点呢?

某人一个月中第三次在游戏中花钱时,弹出一个对话框:“我们感谢您的惠顾,很高兴您想在我们游戏中花更多钱。但您本月已在游戏中消费XXX美元,您确定要再支付XX美元吗?”

也许可以再添加一个复选框:“我有钱,不用再次询问我。”

没错,这样可能会让你赚的钱更少。但你是会结下善缘,晚上睡觉也会更安稳。

我想花钱

零售市场中的交易很简单。如果你想玩《使命召唤》,你必须花钱购买,但其发行商的收益会受到标准零售价的限制。

F2P领域就不同了,你可以使用心理操纵技巧从用户口袋中掏钱——你也可以让他们自愿为你掏钱。无论是哪一种,你的每用户收益只会其消费意愿的限制。

如果他们真的愿意掏钱不是更好吗?

为什么有人愿意为你花钱?

*因为你向他们呈现了价值,他们可以看到这种交易可以让自己访问新内容,或者给予他们目前还没有的能力,或者让他们更快进步。他们理解这种交易,并认为它物有所值。

*因为你已经为他们提供了一种惊人而愉悦的体验,他们就不会在是否花点钱支持你这种事情上斤斤计较。

*因为你在同社区互动时具有响应性、尊重和创新性,他们就知道你是和他们一样热爱游戏的好人。你并不是那种千方百计想骗他们为游戏掏钱的世故投机者,你想提供真正的价值,确保他们愉快消费。

*因为他们对游戏发展(你在信息和论坛上为他们准备的开发内容)抱有更高的期望,知道付费有助于确保游戏继续发展下去。

*因为他们喜欢你,也感觉你喜欢他们。

这是富有道德的F2P游戏设计,它会确保你的玩家会在游戏中逗留,这是进入成熟市场的明智方法,也是让你的游戏永久持续下去的选择。

这里有个称为4X的原则,代表“探索(explore)、扩展(expand)、剥削(exploit)以及消灭(exterminate)”通常情况下,我们总是着眼于“剥削和消灭”,其实我们应该更关注“探索和扩展”。(本文为游戏邦/gamerboom.com编译,拒绝任何不保留版权的转载,如需转载请联系:游戏邦)

Ethical Free-to-Play Game Design (And Why it Matters)

by Greg Costikyan

Long-time game industry veteran and former Playdom senior game designer Greg Costikyan offers a practical look at how ethics in free-to-play design affects a game’s success.

David Ogilvy, an important figure in the evolution of the ad business, once said “The consumer is not an idiot; she is your wife.” He was responding, of course, to what he viewed as cynical and manipulative advertising; but in the F2P market, we — not all of us, but certainly most — are equally guilty of treating our customers as idiots; or worse, as sheep to be fleeced by manipulative and fundamentally unethical business practices. Or to put it another way, we have typically emphasized short-term monetization at the expense of long-term retention, risking annoying our players in order to improve short-term metrics.

Our F2P businesses have, by nature and culture, been highly focused on the short term; startups push to get things done now, to pull in revenues now, and basically have no long-term horizon, or no longer than the three to five years before a hoped-for “exit,” a sale to a larger company or an IPO. I won’t name names, but I know of at least one instance in which a F2P provider purposefully set out to maximize short-term revenues from a game, knowing full well that they were burning their user base and causing the game rapidly to decline, because they were nearing a buy-out and wanted to make this quarter’s revenue growth look good, to support a higher sale price.

As well, our metrics make it very easy to see what happens in the short term, and much harder to determine how things affect the long term; if you make a change to your game, A/B test it, and the metrics say your ARPDAU has increased, the tendency is to say “Great!” and close out the test in favor of your increased revenues.

But what the metrics don’t tell you is that you’ve also done something that annoys your players and, weeks or months later, will increase your user churn; and if you see churn increasing, you will have likely made many changes in the past weeks and months, and it will be difficult or impossible to trace back to determine which changes were most responsible.

And, of course, while our businesses contain many thoughtful and ethical people, it’s also unquestionably true that they contain many cynical bastards who actually believe that deploying psychological trickery to gull people into paying more is good and appropriate business practice.

As a consequence, we see, in the F2P market, exactly what you’d expect to see: F2P games typically have a lifespan of a year or less. They grow, they pull in money, the audience starts to decline, and at some point the operator concludes that life-time value (LTV) is now less that cost of user acquisition (COA), pull the plug on marketing, and the game drops into a death spiral. Existing customers churn out and few new ones enter, with the game being shuttered shortly thereafter.

For someone like me, who has been involved in online games for decades, this is astonishing. Prior to the rise of F2P, online games had the potential to live basically forever; in fact, historically it has been actively hard to kill an online game. I’ll give three examples:

Hundred Years War (hyw.com) began as a computer-moderated play-by-mail in the late 1970s, became an online game on the old commercial GEnie network, and is still played on the open web today.

Gemstone (www.play.net/gs4/) began as a paid MUD on GEnie, and still exists (and makes money for) Simutronics, its developer today — a text-only MMO still with its devoted fans.

Ultima Online (www.uo.com) was launched in 1997 — and continues to this day, with tens of thousands of players, a now-retro 2D MMO in a next-gen world.

And let’s not even talk about Meridian 59 (www.meridian59.com), launched in 1996 and shut down twice by its operators — and still alive today, supported as a free game by its fan community.

Now, you could argue that somehow the business conditions for these games are very different from the F2P market, and that it is impossible to sustain F2P games over the long term; and you would be wrong. FarmVille is the stellar example here; it still has a large and stable user base, and it still constitutes 16 percent of Zynga’s total revenues, four years after its launch, and despite the launch of FarmVille 2.

At the last GDC, Mike Perry gave a talk entitled “Why Won’t FarmVille Go Away?” Which it will not; neither I nor Perry see any reason it can’t last for years to come, and for one simple reason:

Today, although not in the past, it is managed specifically to foster player retention.

The Facebook market is, today, a mature one; there’s plenty of revenue for Facebook games still, but it is not a growing market. The mobile F2P market is still growing fast, but in (at a guess) two to three years, it too will be mature. Mature markets require you to think differently: a gold rush may reward speed and short-term thinking, but a mature market rewards businesses that build customer loyalty. And treating your customers with anything other than respect is no way to do so.

Where does ethical F2P game design come into it? That should be obvious: Treat your customers with respect, and you are behaving ethically. Everything else follows from that simple principle.

The changes demanded by this shifting market will doubtless terrify many who are used to behaving in ways that seemed to work a year or two ago; but we should, in fact, welcome them. Consider:

Would you rather work for a company that has loyal fans eager to play your game, or a company that assumes games are disposable trash, and players, marks to be fleeced?

Respect

Yes, I know, sometimes it’s hard to respect your players, particularly after you’ve just watched a user test with your target demographic and marvel at how clueless they seem to be. Or look over the metrics for your first user experience, and see a big drop off when players are called upon to perform what seem like amazingly simple tasks. Particularly in casual markets, all of your players are clueless, and you need to design with that in mind; but regardless of their cluelessness, they still need to be respected. “All of our users are clueless” and “respect your players” may seem contradictory, but you need to act on both principles: You must both make your UI desperately simple, and your monetization system respectful.

Plan for the Long Term

As I argued above, it’s often very hard to tease out the long-term impact of a change to gameplay from the short-term effects on other aspects. But in truth, common sense and a bit of intuition will get you pretty far; a gate that forces a player to either spam friends or pay money may make you a buck today, but any fool should be able to see that it will drive away players tomorrow.

There’s a reason Pioneer Trail failed; it pulls shockingly hard at the spam gate lever, and players quickly grew tired of it.

What else can help?

For a start, stop thinking of changes as purely things to impact your short-term metrics; think of changes as an opportunity to improve the gameplay. I’ll give Dragons of Atlantis as a (bad) example here; if you look under the hood, it’s pretty clear that the original designer had intended the game to foster a sense of strategy and positional warfare, but the combat system is so brutal that this never happens. You never leave troops at an outpost, because that simply leaves them vulnerable; and you almost never defend your home base (you set your troops to hide) because battles tend to result in the complete elimination of one side, and rebuilding your forces is a tiring, long-term grind. This has been true since the game launched, and despite the many updates Kabam has made, they have never bothered to fix the fact that they basically have a broken combat system — I assume because the game is popular enough, and its producers are focused on changes that improve monetization.

If instead, they actually focused on the player experience, I think they’d realize that losing your whole army through a moment of inattention (or an attacker exploit) is a clear rage-quit moment, and that modifying combat to try to recapture the designer’s original intent would likely produce a game that retains users longer. Perry, revealingly, says that one of the reasons for FarmVille’s continued success is his team’s work to continually add new content and features that surprise and delight its players.

I’m not saying you never make changes with a view to improving monetization; you should. But you should also be trying to make your game better purely from a game design standpoint. Any good live team should contain both a game designer as an advocate for the player, and a product manager as an advocate for monetization — as well as a producer to determine where scarce development resources should be allocated, and serve as a moderator between the two.

Amaze and Delight

We play games because they amaze and delight us — good ones, at any rate. We still often hear that the right way to launch a F2P game is “create the minimum viable product,” launch the game, and if it gets traction, invest in improving it — with “improving it” meaning A/B testing features. To put it more brutally, this approach can be described as “throwing shit against the wall and A/B testing it until it doesn’t stink.”

This doesn’t work, and never has; without a sound core game, no amount of tweaking will save you. And what constitutes a “minimum viable product” is subject to the same ramp up in quality over time as every other aspect of game development; the pure HTML social network RPGs that were successful in the early days of Facebook gaming would never get traction today, because we expect much more from browser games now.

Moreover, it’s now true, in F2P games, as it always has been in the conventional market, that “you only get to launch once.” Data shows that a game’s first cohort, the first people who flock to it, monetize more effectively than later ones; and once you have lost a player, they very rarely return. You want to launch not with a “minimum viable product;” you want to launch with something amazing, because that’s your best hope of snowballing a big audience and achieving long-term success. And of course, you can do geoalphas and short-term tests with small audiences to massage your FUE and your metrics before going full-bore and doubling down on your marketing spend; but you absolutely should not be launching your game broadly until you have something polished and cool.

Your players are not guinea pigs to be A/B tested; they are living human beings, and if you are in the entertainment business, it is your obligation to provide them with quality entertainment, from the very start.

We need to stop thinking in start-up mentality terms, and start putting in the extra 20 percent effort that produces polished games.

Spam Not; Message Endogenously

Time was, you heard a lot of talk in the F2P space about “K-factor.” It’s a term borrowed from epidemiology, actually; K-factor is the number of healthy people infected by one sick person, and in fighting an epidemic, you try to get K-factor as small as possible, by doing things like getting sick people to stay home, wear face masks, take medication, and so on. In games, we use it to refer to the number of new players recruited by each player acquired, and we want to increase K-factor. Once upon a time, Facebook games saw very appreciable K-factors, which meant that a new game could grow by leaps and bounds — and also meant it was clearly in the interest of game developers to get players to send as many messages, and make as many newsfeed and wall posts as possible, because their visibility attracted more players.

So every game encouraged you to post virals at every turn, and in some cases pretty much coerced you to do so — hence the “staffing” mechanic common to so many builders: to open a new building, you need six friends to agree to staff it, invite them today.

I have quit games when staffing requirements became too onerous (14 friends? you’ve got to be kidding); and I am sure I am not alone. They do foster messaging; they are also bad for long-term retention. And what are we planning for again?

Here’s an example of dishonest practice: Most games ask you to invite friends early in the first user experience. Fair enough, as far as that goes: But many also do not allow you to close the pop-up that asks you to invite. There’s only a single “invite” button. The user is forced to click it — or quit. This pops a friends-list dialog, and you can close out of that, and return to your game without sending invites; but you have just told your players “We treat you like sheep and try to trick you into sending virals.” This is the opposite of respect.

A/B test your invite dialog with a close button and not, and I guarantee you will see two things: First, yes, more invites will be sent if there’s no close button. And second — you will see more drop-off at this point in your FUE, as some players say “screw you, I’m not doing that.” In other words, you are trading off keeping this user against the hope of acquiring some other user; which is better in the long term is hard to say, but it is not hard to say, “You are disrespecting this user.” Don’t do that.

Messaging is even more problematic in mobile F2P; yes, a player can easily send messages to someone in their phonebook, or if they signed on via Facebook Connect, to FB friends. But a phone is not a social network, and this kind of messaging is even less natural than it is on a social network; few of your players will do so, unless you force them to — and forcing them to is unethical.

The reality is that K-factor is now small, mainly because Facebook has nerfed the virals (and messages were never a main source of players in mobile). You will no longer see newsfeed or wall posts from games, except for those you already play. Typically, no more than 3 percent of your users will be acquired by virals; is it really worth annoying your players for such a small number?

Virals still are useful in terms of player retention; a player who gets a game message from a friend is more likely to return to the game, which you want, of course. But this is best fostered by positive messaging, like “free gifts,” rather than negative barriers to play.

If you want to foster messaging, don’t force it; instead, make it endogenous to your game, make it fall naturally and comfortably out of your design. As an example, in the (no longer extant) game, Knighthood, you played as a medieval nobleman. If you invited a friend and they joined the game, they began as your vassal — and you received a small portion of the resources they generated each day. This perfectly suited the core fantasy of the game, and provided a strong incentive to send invites; it also served a useful purpose in terms of gameplay, because you wanted to keep your vassals happy lest they leave you for another lord, and therefore had a strong incentive to help them out. Good social engineering as well as good design, in other words.

Stop asking “What would Zynga do?” We know what Zynga would do, and it hasn’t worked out so well for them. Instead, start asking “How can I get my players to want to send messages? How can I make doing so a positive experience for them? How can I build messaging into the core of the game, make it natural, make it emerge spontaneously from play?”

Paying for Content is Always Okay

League of Legends is currently one of the most successful F2P games on the market. As with most F2P games, it has a number of different monetization points, but among its most lucrative is the purchase of champions. It’s a DOTA-style game, and champions are playable characters, each with its own advantages and disadvantages; playing each one is a different experience, they combine with others in interesting combined-arms ways, and there’s always a desire to unlock more.

While the currency used to purchase them can be ground for, it would take an enormously long time to unlock all (and to unlock the “runes” used to further customize champions — which are only available for soft currency, and the main sink for such). Consequently, there’s a strong incentive to pay, at least at times, and many players do.

This is a perfectly honest, and reasonable system; I know what I am getting, and I can see the value. Moreover, if I’m content with playing just one or a handful of champions, I can reasonably get all the runes I want for them without paying; it’s only if I become very attached to the game that I’m likely to pay, and if I am enjoying it that much, I presumably feel I’m getting value for the money. (I’m not claiming LoL’s monetization practices are wholly ethical, by the way; sale of rune sheets strikes me as pretty skeevy; but selling champions is pretty reasonable.)

As another example, Plague, Inc. provides seven playable disease types (for free, in the Android version, or for a buck with iOS), unlockable through play. The impatient can pay to unlock them early; but in addition, there are three additional content packs you can buy, two unlocking diseases that work very differently from the original seven, and the third providing fourteen additional scenarios. Again, an honest transaction, and I have paid for all three packs, and gladly, since I love the game and actively like giving a little money to its developers.

Content, of course, requires development time and money; it is not as lucratively monetizable as consumables or gates. It probably can’t be your only point of monetization; but it is something your players will feel far more willing to pay for than a one-time bypass for a timer. I guarantee you will see a higher percentage of paying players (though not necessarily higher revenues per paying player) if you provide content for pay.

Pay to Progress, Not Pay to Win

Not long ago, Wargaming.net announced that they were removing “pay to win” elements from World of Tanks. This was almost certainly a smart move; the feeling that a game is pay-to-win is a key driver of rage-quit moments, when players decide to leave because the game is pissing them off; if you’re a free player, or one on a budget, it feels hateful if people are beating you just because they have more money than sense.

Clash of Clans handles this in a clever way; as in many games, you can speed your progress through the game by paying to bypass timers, but when it comes time for a battle, you are always matched against a player of roughly equivalent power (based on town center level). If I have a level 6 town center, I will be matched against a player within a couple of levels of mine — and it doesn’t matter whether they got there by grinding or paying, it will still be a fair battle. Paying advances you quicker, but it doesn’t give you an advantage when the battle begins.

Show the Value

A friend who played CityVille once told me “I paid $50 — and it’s gone.” In other words, he liked the game, and was willing to pay — but afterwards, regretted it. He didn’t feel as though he’d gotten value for money. And soon afterward, he was gone, too; he quit the game.

Clash of Clans is one of the few games to have monetized me. It gates the number of buildings you can have under construction at one time with “builder huts.” You start with one, and purchase another with hard currency (a forced purchase) in the first user experience. You see the value at once; more huts means a permanent, secular, continuing speed up in your ability to progress.

Additional huts cost hard currency, and you can grind for hard currency by completing achievements; interestingly, the achievement rewards are rich enough that you can build a third and a fourth hut by grinding (though the fourth hut won’t come in until the elder game, by which time you are more likely to be resource constrained than held up by too few builders). But for $10, you can buy a third hut immediately and have enough hard currency left over that a handful of days’ grind will get you a fourth. That’s pretty reasonable, by the standards of F2P. I liked the game, and was willing to do that. (Paying to bypass timers, not so much, but then, I’m no whale.)

I appreciated that I had the choice: That I could grind, if I preferred. It felt like an honest and reasonable transaction. Interestingly, Backyard Monsters: Unleashed, a similar game, makes your third builder a real-money transaction, and doesn’t let you grind; I’d be interested in knowing whether this works better or less well. It’s still an honest offer, but CoC’s willingness to let me grind made me like the game more; Supercell knows how to monetize, but it pulls gently on the levers. (Well, at least until the elder game, when the slow production rate of dark elixir provides another strong temptation to spend.)

Similarly, League of Legends lets players play some champions for free each week, on a rotating basis. This exposes players to different champions and their advantages and disadvantages; players actively like the opportunity to experiment with them. This undoubtedly leads to additional sales, when a champion is no longer free to play; players who enjoyed that champion’s play style will be motivated to purchase it. Try before you buy, in other words; but in a way that players find positive and unobjectionable.

Grind is Okay; Hard Barriers are Not

Many have decried the level of grind in F2P games, but this isn’t a characteristic of the business model; rather, it follows from the fact that virtually all F2P games are “games neverending,” like MMOs. That is, they do not come to an end and have no winners or losers. In a game neverending, you need to spin out gameplay as long as possible, because you have limited content, and even in the best case, your players will consume your content more rapidly than you expect. That’s why timers lengthen in the mid-to-late game in games that have them; that’s why leveling in WoW requires grinding through mob battles.

Grind is not ideal from a game design perspective; but it’s pretty much a necessity for games neverending. (Which is a reason why I’d love to experiment with F2P games that do come to periodic conclusions, but that’s another story.)

And it’s acceptable to allow players to speed up or bypass the grind for purchase; what isn’t acceptable is make progress either impossible or insanely difficult without paying. Some levels in Candy Crush, for instance, are (seemingly) purposefully designed to require dozens or even hundreds of attempts to get past unless you pay for additional moves or powerups.

Interestingly, King seems to have nerfed some of these levels over time; I have no doubt they responded to player complaints, but also that they A/B tested the change. So I think we can posit that, yes, pulling on the monetary levers more gently has been successful in increasing their long-term customer value; better to keep them playing with the hope of monetization in future than cause them to rage-quit.

Of course “insanely difficult” is a fuzzy phrase; but the point is that you’ve made a promise to players that they can play, and grind, without paying, if they so chose; you have to keep that promise, and that means more than just “you have a tiny chance of being able to progress.”

No Bait and Switch

Marvel Avengers Alliance has monthly “spec ops” releases. A spec op is a series of linked battles (with a story arc attached); players who complete the series within a set period of time, usually a couple of weeks, get a new playable superhero for free.

However, each of the battles in the spec op requires expenditure of a currency available only for the duration of the spec op (called “unstable ISO”). Each time you initiate a battle in the series, you expend some of it. Players are seeded with a certain amount, but not nearly enough to complete the sequence.

Players can gift each other unstable ISO, but the amount a player can receive per day is strictly limited; and unstable ISO can also drop as a reward during a battle. In short, the developers can constrain the amount of unstable ISO a player can earn by adjusting the “receivable per day” parameter, and the drop rate in battles.

There are intermediate rewards over the course of the spec op; that is, at some point in the mission sequence, a player will be rewarded with a rare weapon, or a small quantity of hard currency, or something else of value. Players of the game actively like spec ops, because they provide new, periodic content, there’s a tasty reward at the end of the sequence, and even if they are unable to complete it, they can receive the intermediate rewards.

Needless to say, unstable ISO can also be purchased for real money. And since the superheroes rewarded by a spec op are later put up for hard currency purchase, it is possible that, by purchasing a limited quantity of unstable ISO, you may be able to obtain the superhero for less than the outright purchase cost.

Is this system unethical? I would argue that it depends. If the game’s parameters are tuned so that, with optimal play (maxing daily unstable ISO gift reception, losing few to no battles, spending the time to grind), a player can complete the series, then it strikes me as ethical: You’re giving players more content, and non-payers can still succeed, though they have to work at it.

If, however, the parameters are tuned so that players literally cannot complete the sequence without paying, then it strikes me as unethical. It’s a bait and switch; it’s like Lucy pulling the football away from Charlie Brown. You’re holding out a reward and giving players the impression that they can get there by grinding, but denying them that opportunity. Players will wise up to this, eventually — and you will lose some who do.

Make Friends and Advocates of Your Players

We need to relearn the dark arts of customer service and relationship management. MMO developers know this well; they know how important the forums are, how fans can serve as ambassadors for the game, how what gets said on the forum can raise warning flags early when updates cause problems, how sometimes some of your best ideas can come from your players. Yes, it’s true that this kind of information is anecdotal, while your metrics are hard data; that players sometimes don’t really know what they want; that players often misidentify a problem (e.g., they say something is “too hard” when really it’s too boring); and that quite often you can’t do as they wish, because market conditions don’t permit it. Of course you keep analyzing your metrics, too.

In the F2P space, by contrast, customer service has been treated as a cost sink, something to be ignored or minimized; many games make it actively hard to find anyone to help when you have a problem. Even when there is a customer service function in the organization, it often is isolated from live teams, with only a trickle of information back from CS to the developers — and almost never any information from the dev team to players in advance of updates. This is no way to foster a community.

Customer service is not a cost sink; customer service is an opportunity to retain players you might otherwise lose — and given how much money you spend acquiring players, retaining them is valuable. A customer in hand is worth two in the bush.

Let Them Set a Limit

The F2P market has been dinged on the fact that most games rely on whales, a small proportion of the audience who spends disproportionately. This raises no ethical issues if your whales are princes from Saudi Arabia or tech-boom millionaires; it is an issue if someone living in a trailer park is spending $5000 they can’t afford.

Why not be super-ethical?

The third time within a month that someone makes a real money purchase, pop a dialog saying, “We appreciate your business, and are very glad you want to spend more on our game. But you’ve already spend $XXX this month. Are you sure you want to spend another $XX?”

Likely with a checkbox saying “I’m fabulously wealthy, don’t bother me with this again.”

Yep, you’ll likely make less money. But you’ll build good will. And maybe you’ll sleep better at night.

I Want to Pay

In a retail environment, transactions are simple. If you wish to play Call of Duty, you must pay to purchase it — but the revenues of its publisher are capped at the standard retail price.

F2P is different. You can use psychological techniques and ethically dubious tricks to slide bills out of your customers’ wallets — or you can get them to want to pay you. And either way, your per-customer revenues are capped only by their willingness to pay.

Isn’t it better if they are truly willing to pay?

Why would someone want to pay you?

Because you’ve shown them the value; they can see that this purchase will provide access to new content, or give them capabilities they don’t currently have, or let them advance more quickly.

They understand the transaction, and find it worthwhile.

Because you’ve provided them with an amazing and delightful experience, and they don’t mind giving you a little money to support you and your future efforts.

Because you’re responsive, respectful, and creative in your interaction with the community; they know you to be good guys who love games as much as they do. You are not cynical vultures tricking them into something dubious; you want to provide value for money, and to ensure that they are happy with the exchange.

Because they anticipate and hope for even more amazing developments in the game — developments you’ve primed them for on the forums and in your messaging — and know that paying helps ensure the game will continue and grow into the future.

Because they like you, and have the sense that you like them.

That is ethical F2P game design; that’s what will ensure that your players stick around; that’s the smart way to approach a mature market; and that’s what will make your game last, potentially forever.

There’s a genre called 4X: that stands for “explore, expand, exploit, and exterminate.” Too often, we concentrate on “exploit and exterminate.” Let’s focus more on “explore and expand.”(source:gamasutra)

上一篇:列举宣传和推广手机游戏的9个要点

下一篇:如何通过客服支持策略提高转换率

闽公网安备35020302001549号

闽公网安备35020302001549号