分析游戏用户研究方法种类及其优劣(1)

作者:Ben Lewis-Evans

我将在本篇文章以及接下来的后续文章中阐述开发者能够用于游戏用户研究中的一些不同方法。

在此我将涉及游戏用户研究的某些要点,并详细讨论3种方法,焦点小组,启发式评估以及问卷调查等内容。

什么是游戏用户研究?

开始之前我们必须先搞清楚什么是游戏用户研究?首先,让我们将其与质量保证(QA)进行比较。QA是软件开发过程中的一大组成部分,并且总是由一些开发团队中一些专业人士去执行这一任务。这些专业人士的主要目标便是寻找漏洞并确保游戏的顺利运行。

然而,由一些致力于某一项目的人员去执行QA也就意味着这些人士非常专注并熟悉这项工作。而这恰好也是问题的根源,特别是涉及游戏可用性和游戏体验的评估时。因为对于那些专注于项目中的人员来说,他们认为很明显或者很有趣的内容对于新用户来说可能是完全陌生且让人沮丧的内容。

所以这时候便需要游戏用户研究方法的介入——即完全专注于用户以及他们游戏体验的领域,并且这一领域所关注的主要问题是“玩家是否会觉得游戏有趣?”

简单地来说,QA和测试是关于软件,以及它是如何在用户面前运行的,而游戏用户研究则正好相反,它是关于用户,以及用户是如何面对软件。

所以,如何才能做到这一点?并且什么才是真正的乐趣?乐趣是一种很容易使用的元素,但是它同时也会伴随着奋斗和挑战的出现。有趣的体验,吸引人的体验或者轻松的体验都能够为玩家带来乐趣。

如此看来乐趣是一种主观的变量,即不同人在不同情境下对于乐趣的感受也不同。而因为乐趣拥有情感成份,所以可以说当玩家在你的游戏中感到乐趣时,他们便会想要告知你——但是前提是你必须知道如何去询问玩家的这种反馈。

那么应该如何询问玩家的反馈呢?

在开始阐述细节内容之前我想先列出一些重要的基本原则:

明确目标玩家

不论你选择的是何种方法,你都需要明确正确的玩家。这就意味着你需要获得富有代表性的用户,也就是那些你希望能够玩这款游戏的玩家。

如果你拥有大把的时间,你当然能够尽可能地拓宽用户群体(如果你真的认为所有人都会喜欢游戏的话),但是通常情况下你总是会受到时间(以及金钱)的限制,所以你最好能够专注于那些你所明确的目标玩家。

测试游戏而不是玩家

其次,当你在进行这类型的研究时都必须确保让玩家清楚自己并不是测试对象。研究是关于如何完善游戏而不是玩家,所以即使玩家在某一方面做得不好也不用因此感到自责。原则上来看,他们所提供的所有反馈(不管好坏)都是非常有价值的信息。

但是做到这点却不容易,因为你参与了游戏设计工作,所以如果听到别人对于游戏的批评肯定会感到不舒服。但是不管怎样你都要想办法克服这一障碍而让自己更加客观地接受玩家反馈。

明确自己要了解的信息

每当你在进行研究时,你都需要明确自己想要知道哪些内容。你在创造游戏时肯定会亲自尝试游戏,并且因为你拥有明确的设计文件,所以你知道游戏中的每个环节是如何运行的。所以不要责怪那些输掉游戏的玩家,而是仔细想好自己要问他们哪些问题。仔细思考哪些区块是问题所在,并在测试之前搞清楚自己想知道些什么。

请注意:我并不是说你们带有偏见或者已经“知道”自己想要的答案;我只是希望你们能够准备好并知道自己真正在寻找哪些内容,否则你将只会收到一些无用的信息。同时,你还需要学会处事不惊,因为你根本不知道自己会收到哪些答案。

尽早且频繁地进行测试

这是用户研究中最重要的一点,也就是你应该在自己认为合适的时间尽早进行测试。但是做到这点却很难,因为你可能在游戏还未完善之前就将其暴露在用户面前。但是你却可以因此更早地进行测试——例如测试纸上原型。

如果能够尽早进行测试,你便能够及早发现问题并即时做出修改。而当你做出修改后,你必须再次进行测试。也就是说你最好确保游戏不会漏洞百出,因为当你在测试游戏体验时,你肯定不希望因为漏洞而破坏体验。

一种有效的方法便是微软的游戏用户研究员所研发出来的快速迭代测试和评估方法(RITE)。在这一方法中,研究员需要不断运行测试(经常是通过行为观察),并在发现问题时立刻进行修改(直到面向下一名测试者)。有可能在第一名测试者完成测试时便会发现问题。

听取问题并付诸行动,但是测试者所提出的却不一定是解决方法。

当你在面对用户时,你需要足够开明地听取他们所提出的各种问题。你同样也可以听取他们所提出的解决方法——但是这一方法对你来说不一定有用。你是游戏开发者,所以你知道该使用自己所拥有的技术,时间和资源完成某些内容。但是你的玩家却不行。所以当玩家提出相关问题时你一定要正视它,并进行一定的研究,但对于玩家所提出的解决方法你可以持保留态度。

游戏用户研究是另外一种数据来源

通常情况下像我们这类文章发布到网上时,便会有人担忧这些研究是否会破坏游戏的艺术性或者是否会催生出“评委式设计”等问题。当然了,我理解这种担忧,但是与QA一样,用户研究也只是帮助你完善游戏的一种工具罢了。它不会主导你的设计或压制你的艺术才能;而如果你能够合理利用这一工具,不仅你的才能有望得到进一步扩展,你还能够以一种全新的视角去看待游戏。

细节内容

我将在之后的内容中从各种深度分析:焦点小组,启发式评估和问卷调查。

焦点小组

这一方法本身就存在一定的问题(其实它也是“评委式设计”问题中的一环)。所以我们将最先解决这一问题。

你可能已经非常熟悉焦点小组了——尽管你可能从未亲眼见识过。基本上来看,焦点小组就是你号召一群人来玩你的游戏,然后将他们汇聚在一个房间里谈论游戏。他们可以很自由地谈论自己的观点,不管喜不喜欢你的游戏;而你需要在房间里安排了一名引导者,负责询问一些特殊问题。

我们也可以在开发的早期阶段使用这一方法(而不是让人们单纯地玩你的游戏),即你可以阐述关于游戏的相关理念并获得相关反馈。

焦点小组的优点便是它们总是包含许多参与者,而你能够因此获得更多反馈。这是一种相对有效的方法,即所有人都聚集在一处地方,由引导者负责向他们提问。所以如果有人提及他们喜欢或不喜欢的内容时,你应该让他们更加详细地说出原因。

如果处理不当的话,焦点小组便会成为一种浪费时间的无用方法。所以为了避免这一问题你就需要安排一名优秀的引导者去组织你的焦点小组。引导者必须拥有足够的能力以有效地引导对话,同时也不会绝对地主导着小组成员的讨论。

焦点小组所存在的最大风险,也是为何研究员很少使用这一方法的最大原因便是:有1至2名的焦点小组成员会主导整个讨论。迫于小组的压力,你甚至不会听到其他人关于游戏的更有价值的想法。并且焦点小组总是倾向于讨论问题的解决方法而不是问题本身。而这正好都不是你所希望看到的。

最后,焦点小组还是一种非常主观的方法,也就是我们所获得的反馈都是来自于不同人的看法,我们还需要去判断他们所持有的不同“态度”,思考他们的可能性行为,并且我们也清楚人们不一定总是会按照自己所说的去行动。

优点

参与者越多也就意味着能够收到越多反馈

能让所有人汇聚到同一个地方

允许在讨论后提出问题

如果是讨论理念便非常有帮助

缺点

要求必须要有一名优秀的引导者

主导者总是会抢尽风头导致其他人不能发表自己的见解

一窝蜂地讨论解决方法而不是问题所在

人们的所言并不一定是其所行

启发式评估

启发式评估是指你找到游戏用户研究领域的专家,让他们帮你玩游戏,并基于一定标准(启发法)进行评估。有点像系统式游戏评估。

基本上来看,这些专家都需要使用一系列启发法——一些基本规则或心理模式,反馈你的游戏是否匹配这些启发法并提出问题所在。启发法多种多样,我将在此列出Christina Koeffel及其同事在2009年所列出的一些可能的启发法:

是否提供了明确的目标?

是否提供给玩家有意义的奖励?

玩家是否能够掌控局面?

游戏是否保持平衡?

游戏是否留给玩家一个好印象?

游戏中是否拥有一个好故事?

游戏是否能够有序地发展?

游戏是否具有一致性并且能够得到响应?

玩家是否能够清晰地知晓自己失败的原因?

游戏中是否拥有各种难度等级?

游戏以及游戏结果是否公平?

游戏是否具有重玩价值?

游戏的AI是否明显,是否一致,或者是否存在一些不可预知因素?

游戏是否会让玩家感到沮丧?

游戏中的学习曲线是否过于起伏不定或者太长?

有何情感影响?

是否存在过多无趣的重复内容?

玩家是否能够认出屏幕上的一些重要元素?

我认为启发法最让人惊喜之处便在于即使你不是专家,你也能够基于这一系列内容更好地去思考你的游戏。例如,你的游戏是否提供给玩家足够的反馈,并让他们知晓自己的行动对游戏世界会产生何种影响?游戏是否强迫玩家以一种笨拙的方式去使用控制器?当然了,这些都是一种常识,但是你常会发现这些所谓的“常识”却并不为人所正视。

而启发式评估的一个明显的优势便在于你只需要使用少数的专家(有时候甚至只需要一名),并且专家们也总是清楚自己在讨论些什么。但这一优势同时也是问题所在,因为你需要思考该去哪里才能找到这些专家?以及你是否能够找到合适的专家?不同专家可能会使用不同的启发法,而你还需要确保这些启发法能够适用于你的游戏——这一点非常重要。

但是有时候专家其实都太过专业,常常会忽略一些新手们可能会遇到的问题。这是因为当我们变得更加有经验时我们便不会下意识地考虑那些我们所察觉到的一切,然而那些仍然处于学习阶段的人却仍需要思考这些内容。这也是为何想要做好一件事需要遵循专家的做法,而想要学习一件事则需要咨询新手的道理。

优点

不需要太多人参与

能够较快速地解决问题

专家就是专业人士

缺点

你要去哪里寻找这些专家?

你是否能够找到合适的专家?

专家都太过专业

问卷调查

你肯定知道什么是问卷调查,但是你是否知道如何正确设计并使用这一方法?

首先,你需要清楚何时能够使用这一方法?问卷调查是关于玩家对于你的游戏的主观评价,特别是关于价值的判断。而这些调查的范围更是广泛,包括玩家喜欢何种武器以及一些更开放的问题如他们对于游戏体验的总体评价等。

开发者能够在游戏期间向玩家发放问卷调查,因为这时候他们正切身感受着游戏体验——但是这么做的风险则是会打断玩家的游戏进程(游戏邦注:所以开发者最好寻找一些更加合适的暂停时间去提出这些问题)。开发者也能够在游戏结束后进行问卷调查。而问卷调查的一大优点便是它是面对大众群体,也就是开发者能够因此获得更广泛的研究数据。

在详细阐述如何创造属于你自己的问卷调查之前,我想先列举出一些致力于评估游戏体验乐趣的问卷调查案例。

这类型问卷调查的例子包括“游戏体验问卷调查(GEQ)”——用于调查玩家的游戏体验以及影响规模或者针对于不同情感等级的人体模式系统。这些问卷调查都非常优秀,因为其中的问题都是设计师精心设计而成的,可以说都是可信赖的问题。但是通常情况下这些问卷调查问题更倾向于学术性,所以你需要谨慎设置这些问题以让它们能够更好地反映你的游戏,并在适当的时候做出调整。

所以,你到底该如何设计你自己的问卷调查?以下我将列出四大步骤:

步骤1:明确你想知道些什么

就像之前所阐述的,所有的这些方法都需要你事先明确自己想要了解的信息。特别在问卷调查中更加重要。因为你不可能不断追踪着每个玩家的答案,所以你肯定希望他们能够尽可能清晰地回答你的问题,并且你也需要确保你所获得的信息就是你想要知道的内容(保证这些问题不会太多也不会太少!)

你可以通过头脑风暴,制作列表等一系列方法明确自己到底想了解些什么。然后再进行压缩,留下那些自己真正需要知道的内容。切记一定要有所侧重!

新手研究员经常会犯的一个错误便是认为机会很多而一直问一些非常简单的问题。但是如此便会创造出一大堆需要分析的数据并最终促成一些没有意义的结果。除此之外,你肯定也不希望玩家需要投入超过15至20分钟的时间去回答你的问卷调查吧!

步骤2:设计内容

内容的设计是创造问卷调查的核心内容,我们可以将其分解为以下内容进行分析。

问题或陈述?你希望调查对象是回答问题还是进行陈述?这一点非常直接但同时也非常重要。一般来看,问题更能够帮助你获得想要的信息,例如:

Horrible Bog Beast具有多大的挑战性?

1 2 3 4 5 6 7

非常简单 非常困难

问题也能够以指令的形式表现出来。例如:“根据1至6个分数点为你刚刚玩过的游戏关卡评级,1代表你非常喜欢这一关卡,而6则代表你非常讨厌它。”这是一种非常有效的方法,就好象你在询问每个人对于不同关卡的评价等级一样。

Horrible Bog Beast是玩家所遭遇到的一个有趣的敌人。

1 2 3 4 5 6 7

强烈赞同 强烈反对

问题也好陈述也罢,你都应该为你的游戏选择最适合的方式,并且不要在同一份问卷中频繁地转换不同方式。

语言的使用。你必须使用那些耳熟能详的日常用语;避免使用晦涩的专业术语。如此你才能够确保你所询问的对象能够理解你的问题。很多研究员只是简单地提出问题,有时候甚至都不理解自己的问题(我敢保证很多人都这么做过),如此他们最终只能够获得一些没有用的信息。所以切记一定要直接提出那些你真正想知道的问题!

当你提供了一些问题的可选择答案时(游戏邦注:例如他们不得不从自己所拥有的控制台列表中做出选择)。你必须确保这些答案足够详尽。换句话说,你必须好好思考这些可选择答案。在此添加其它额外选项很有帮助,但是前提是不要频繁使用这种“其它”选项。

同时你还需留意不要问一些重复的问题(即使是基于不同方式)。一定要尽可能地压缩问题。避免出现任何消极语气;也就是基于肯定的语气而不是否定,如“我喜欢跳跃机制”而不是说“我不喜欢跳跃机制”。就比如说在消极语气问题中,人们便不得不逆向思考到底要选择“同意”还是“不同意”,而因此混淆了问题与自己的答案。

避免出现诱导性问题,双重问题以及含沙射影式问题。诱导性问题是指人们会被引导着而给出一个肯定的答案,如“这是一款有趣的游戏。而它的趣味性在哪?”当然了,这个例子太夸张了,但是你还是得正视这一点,因为实在有太多问卷调查中出现了这种类型的问题。所以请一定保持提问措辞的直接与中立。不要装腔作势!

双重(或多重)问题指同时影射多个问题。我将列举一个游戏外部的例子,即新西兰的公民投票进行说明:

“我们是否应该改革司法制度,更多地强调受害者的需求,提供给他们赔偿,并以最低的刑罚和较重的苦役判定任何严重的暴力犯罪?”同意/反对

我们可以看到在这个疑问句中至少出现了六个问题,包括是否需要进行改革,是否需要更加强调受害者的需求,是否应该提供赔偿,是否应该执行最低刑罚,是否应该施以苦役,是否应该面向所有严重的暴力犯罪?但是你却只能回答一次。正如我所说的,这一问题是面向整个新西兰的民众,但是却严重地破坏了他们的投票体验。

含沙射影式问题是指做出一些道德上的判断或没有根据的假设;同样以新西兰公民投票中的一个问题作为例子:

“在新西兰应该将打巴掌这一良好的管教孩子方法视为刑事犯罪吗?”同意/反对

这个问题使用了一个道德术语,即“良好”;同时它也使用了一个不够明确的表达,即“良好的管教孩子方法”(不管是什么方式),并最终造成了一种误解,即反对打巴掌的人不得不回答“同意”而赞成打巴掌的人则需要回答“反对”。

封闭式或开放式?问题可以是开放式的,也就是玩家可以随心所欲地说出自己的想法;也可以是封闭式的,即给出玩家一定的选项让他们做出选择。

开放式问题能够帮你收集到更多信息,因为它能够让玩家尽情地阐述反馈。但与此同时它也会产生局限,并且因为没有明确的方向而导致所有的问题变得更加含糊。

所以如果你选择开发式问题你就需要尽量确保拥有足够的时间阅读这些问题,以防你可能会要求回答者解释他所给出的答案。但是如果你的问卷调查是远程发放(游戏邦注:如通过电子邮件或在线发放)的,你便很难做到这一点。

而如果是封闭式问题你便可以通过不同衡量法掌控参与者的答案:

二分量表:也就是最简单的是与否的问题。通常情况下这是用于收集一些肯定与否定,正确与错误之类的信息。尽管这种方法非常直接,清晰,但是它却不能创造出多少信息。所以这种问题只能用于收集人口统计资料,或者当你必须在两个选项中做出选择时使用。

连续量表:也就是要求人们沿着数值的增减或基于比例增减做出选择(游戏邦注:就像你在游戏中定制角色的脸部比例)。这种方法的一大优势便是能够给出明确的衡量数值。但是通常情况下过于明确的数值也没有多大的用处(就像96.43与93.21又有多大区别呢?)

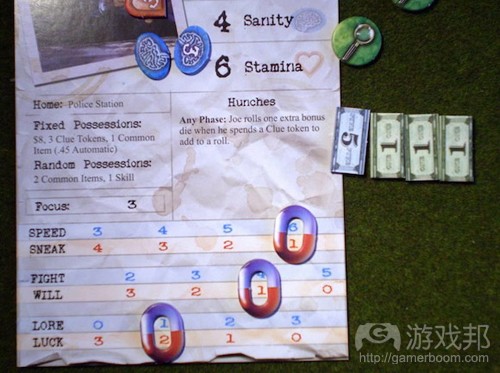

等距量表:这是我们最熟悉的一种量法类型。在此你可以基于一些相互分离的步骤而做出等级评定。

比起连续性选择,这种方法虽然会降低量表的精确度,但是我们却能够因此更好地比较结果。依我看来,1至7的量表是最合适的选择,因为这一范围的精确度也是最合理的,不会过宽。

如果你选择了等距量表,你就需要进一步将其分解为以下类型:数值量表,李克特量表(游戏邦注:是一种心理反应量表,常在问卷中使用)或语义量表。

数值量表非常简单,你只要使用一些数值进行提问即可。这种方法经常用于评级中。

李克特量表是最频繁出现的一种方法,当你想要知道有多少人表示赞同或者反对时便能够使用这一量表,例如在1至7的数值范围中,1表示强烈反对而7表示强烈赞同。

语义量表常用于单纯的评级或价值判断中,例如在1至7的数值范围中,1代表最糟糕而7代表最优秀等。

你可以基于不同需要使用不同量表,但是最好不要过度混合使用;否则将会误导回答问题的群众,让他们不知道是该直接回答同意或不同意,还是需要逆向进行思考。

除此之外在等距量表中,你可以提出单级问题(以程度去区别变量),如在1至7的数值范围中,1代表不是很有趣而7代表非常有趣,或者是双极问题(即对比两个变量),如1代表非常无聊而7代表非常有趣。单级变量能够更深入地表现出同一种情感,而双极变量则给予人们更多的空间去传达他们的想法。切忌在同一份问卷中过度混合使用这些不同类型的量表。

步骤3:整合在一起

现在你已经明确了自己想知道哪些问题了,接下来你就需要将它们整合在一起。首先,思考你需要使用何种媒介,也就是你想通过电脑还是纸发放你的问卷?如果可能的话,通过电脑发放问卷更加有效,因为你不需要在之后进行额外的数据输入,但是如果从可携带性和易用性来看,纸上问卷则更胜一筹。

你应该投入更多时间去做出选择,如果你决定使用基于电脑的调查方式,你可以寻求一些专业公司的帮助(有很多专门提供问卷调查服务的公司),SurveyMonkey便是一个非常好的选择。

接下来你需要考虑问题的排列顺序。一般来讲我都会建议研究员将最简单的问题放在最前面。这样才不会让回答者感到厌烦——只要你的问卷不会过长,他们也会愿意回答你之后提出的较困难的问题。

基于一种合理的模式或者它们所涉及的内容将剩下的问题整合在一起。不要再问过大量关于武器的问题后一下子跳到boss身上,然后又转回到武器上。

确保你在问了一些问题后能够排除一些不可能的问题或相对应地衍生出一些新问题,也就是如果你问的是“你是否拥有Xbox”有/没有,而回答没有的人则不需要列举出他们所拥有的前10款Xbox游戏。

步骤4:测试

任何计划都需要与玩家进行第一次接触,所以你就需要先亲自测试你的问卷调查。如果你使用的是基于电脑的问卷调查,你应该尽可能保证你最终获得的信息是良好。然后邀请其他人(最好是那些不熟悉你的游戏的人,并且最好不是游戏设计师)去填写你的问卷调查(而此时的你不应该与他们待在同一个房间,所以不可能帮助他们回答问题),并询问他们对于该份问卷的意见。基本上来看,问卷的测试过程也是遵循用户测试,提出一些问题并且你予以改进(然后继续进行测试)的过程。我知道这是一项相对繁琐的工作,但是一旦你拥有了一份完善的问卷,你便能够在今后重复使用它(或至少利用其中一些有帮助的内容)。

优点和缺点

问卷的最大优点便在于你能够同时面向许多人提出相同的问题,也就是你可以获得一致的可量化数据,并基于这些数据去比较不同人的看法。

但是这种方法却缺少后续过程,也就是你不能够询问人们为何他们选择这一级别;这并不是一种绝对客观的方法,而如果你希望获得一些可靠的结论你便需要投入额外的努力。即当你针对于某些人进行测试时,你所提供的问卷只能帮你获得这些人的观点而已。

优点

一致性

足够量化

能够快速进行管理

可以大规模地使用

缺点

缺少后续过程

不够客观

至多只能代表接受测试者的观点

整合一份优秀的问卷需要投入不少时间

最后,我想说的是我在此所阐述的内容还不够全面,但是至少我希望它们都是有帮助的。而在之后的系列文章中,我将进一步涉及面谈,观察法,游戏参数以及生物统计学等内容。

(本文为游戏邦/gamerboom.com编译,拒绝任何不保留版权的转载,如需转载请联系:游戏邦)

Finding Out What They Think: A Rough Primer To User Research, Part 1

by Ben Lewis-Evans

This article, and its forthcoming followup, is intended to give a rough idea to developers of several different methods that can be used in games user research.

However, many, many books have been written on research methodology and I cannot cover everything. Therefore these two articles cannot be taken as completely comprehensive.

In the first of the articles I will be covering a few general points about Games User Research and then discussing three methods, focus groups, heuristic evaluation and questionnaires in some detail.

What is Games User Research?

So, before getting really started, what is games user research in the first place? Well, let’s start by comparing it with Quality Assurance (QA). QA is a well-established part of software development, and is often carried out by professionals within a development team. These folks are, generally speaking, aimed at finding bugs and making sure the game runs smoothly.

However, because those working on a project usually carry out QA, it means they have an investment in it, and are familiar with it. This can cause problems when it comes to evaluating the usability and experience of a game. What seems obvious and fun to someone that has been working on a project may be completely alien and frustrating to a new user.

This is where games user research methods come in, a field that is all about the user and their experience of the game — in particular, the big question, “is it fun?”

To really (over) simplify things, it could be said that QA and test is about the software, and how it functions when dealing with users, and game user research is about the user and how they function when dealing with the software. Notice I say just it is about how the user functions when dealing with the software, and that it is NOT about testing the user (more on that later).

So how is this done? And what is fun, anyway? Well, there has been plenty written on fun already, so let us just say that fun has quite a few dimensions. Fun can be something that is easy to use, but it can also come along with a struggle and a challenge. It can arise from an engaging experience, a compelling experience, or a relaxing one.

All this means fun is a subjective variable, which changes from person to person, and situation to situation. However, due to the emotional component of fun, what can be said is that if your players are having fun, then it is likely they can tell you about it — if only you know how to ask.

So How Do We Ask?

Okay — I’ll get to that. But before I get into the fine details, please bear with me as I outline some general principles to keep in mind:

Get the right players

Whatever methods you choose, make sure you get the right sample. For most methods, this means getting representative users, aka the people that you expect will play your game.

If you have the time, perhaps there is some advantage to getting as wide and large a user group as possible (if you really think that everyone will want to play your game), but given that you are likely to be constrained by time (and money) it is generally best to concentrate on getting as close a sample of the target type of player you are after as possible.

The game is being tested, NOT the user

Secondly whenever doing this type of research make sure it is clear to the user that they are not being tested. The research is about improving the game, not the user, so the user shouldn’t be made to feel inadequate if they can or cannot do something. In principle it is all valuable information.

This can be hard to do sometimes, as you are the ones designing the game, and it can be uncomfortable to hear others criticising it. But try your best to not be defensive or judgemental (i.e. avoid thinking the problem exists between the keyboard and chair.)

What do you want to know?

Whenever doing research, you should be clear about what you want to know. You will be playing the game yourselves as you work on it, and you should have design documents, so you know how things are supposed to work. So don’t just plonk people down with the game and come up with questions on the fly. Work out what areas you think might be problems and know what you want to ask about before it’s time to test.

Please note: I am not saying you go out there with preconceptions and already “know” the answers you want; rather I am just making the point that you should be at prepared and know what you’re looking for. Otherwise, you get a mass of data that may not be of any use to you at all. At the same time, be open to surprises. You never know what might pop up.

Test early and test often

The next point is considered one of the most important by user researchers, and that is to test as early as you feel it is possible to do so. This can be difficult, as it feels bad letting your baby out into the hands of users before it is 100 percent compete. But really, the sooner you can test the better — test with paper prototypes, for instance!

The primary reason for this is that it is much easier to change the game if you find an issue early in development rather than late. Once you have made the changes, you should test again. That said, it is also a good idea to make sure that the product isn’t too buggy; you want to test the experience of playing the game, not the experience of crashing due to bugs.

One extreme example of this approach is the Rapid Iterative Testing and Evaluation (RITE) method, developed by games user researchers at Microsoft. In this method a test is run (usually via behavioural observation — which will be covered in the second article in this series), and changes are made to the game as soon as problems or issues are detected, before the next participant arrives. This can occur perhaps even after just one user has been tested.

Listen to and act on problems, but not necessarily the solutions

When dealing with your users, you should be open, and listen to the problems they are raising. You can also listen to the solutions they give to those problems — but they are likely to be less useful to you. You are the game developers, and you know what is possible with the technology, time, and resources you have. The users won’t. So observe, do the research, and treat it seriously when it reveals issues, but take suggestions from users as to how to solve the issues with a grain of salt.

Games user research is just another source of data

Often when articles such as this appear online, there is much gashing of teeth and angst about taking the art out of game design and instituting “design by committee”. I can understand this worry; however, much like QA, user research is just another tool to improve your game. It shouldn’t dominate your design or suppress your artistic talent; rather, if done correctly, it should augment your talent and give you new insight.

Time for the Crunchy Stuff

Are you still with me? Great. Here, then, are the research methods that I will cover, in varying degrees of depth, in the rest of this document: focus groups, heuristic evaluation, and questionnaires/surveys.

Focus Groups

This method can be something of a dirty word (and is definitely part of that whole “design by committee” problem). So let us deal with it first and get it out of the way.

You are probably familiar with focus groups, even if you’ve never seen them used in person. Basically this is where you get a bunch of people, have them play your game, and then put them in a room to talk about it. They can be free to talk about what they like and what they didn’t like, but you also have a facilitator in the room who can ask specific questions of interest.

This process can also be used quite early on in development, where instead of getting people to play the game, you give a presentation or talk about ideas for the game and get feedback on that.

The advantages of focus groups are that they involve a lot of people, so you can get more feedback. They can also be somewhat efficient, as everyone is together in one place, and the facilitator can ask follow-up questions. So if someone mentions they like or dislike something in particular, you can gain a bit more detail on why.

Although at the same time if you are not careful, focus groups can get away from you, and end up wasting far too much time. To avoid this last problem you really need a good facilitator to run a focus group. The facilitator has to be strong enough to guide the conversation to areas that are useful, but not dominate the discussion.

Probably the biggest risk with a focus group, and one of the reasons why focus groups are not often used, is that just one or two members of the focus group can dominate the discussion. Due to group pressure, you may not hear from other people who have valuable insight into the game. Focus groups also have a tendency to get more into discussing solutions for issues rather than just the issues themselves. This is not what you want.

Finally, focus groups are a subjective method, and all you have to go on is what people say — and as much as we like to judge people on the “attitudes” they hold, and think that they predict behaviour (they usually don’t), we all know that what people say is not always what they actually do.

Pros

More people can mean more feedback (although see cons…)

Gets everyone together in one place

Allows for follow-up questions

Can be useful when discussing concepts

Cons

A good facilitator is required

Strong voices may take over and reduce feedback overall

Too many solutions, not enough issues

What people say is not always (or even often) what they do

Heuristic Evaluation

Heuristic evaluation is where you get an expert (or experts) in games user research, get them to play your game, and then they evaluate it on a set of criteria (heuristics). Kind of like a scientific game review… Kind of.

Basically, to do this, the expert(s) will use a list of heuristics, which are basically rules or mental models, and give you feedback on whether your game fits these heuristics, and where problems might come up. These heuristics can vary, but here is a selection of some possible heuristics listed in a 2009 article [PDF link] by Christina Koeffel and colleagues:

Are clear goals provided?

Are the player rewards meaningful?

Does the player feel in control?

Is the game balanced?

Is the first playthrough and first impression good?

Is there a good story?

Does the game continue to progress well?

Is the game consistent and responsive?

Is it clear why a player failed?

Are there variable difficulty levels?

Are the game and the outcome fair?

Is the game replayable?

Is the AI visible, consistent, yet somewhat unpredictable?

Is the game too frustrating?

Is the learning curve too steep or too long?

Emotional impact?

Not too much boring repetition?

Can players recognize important elements on screen?

The article itself lists over 29 of these heuristics, and goes into much more detail than I have provided here, so I recommend reading it if you have the time.

The good thing about heuristics, in my opinion, is that even if you aren’t an expert, they can provide a list of things for you to think of when you look at your game. For instance, does it provide enough feedback to players that their actions are affecting the world? Does it force players to hold the controller in an awkward fashion? And so on. Again, this may seem like common sense stuff, but it really is amazing how often so-called “common sense” is not common at all.

Now, one obvious advantage to heuristic evaluation is that you only need to use a small number of experts (just one in some cases), and being experts they know what they are talking about. This also leads to the problem that you do need experts, and where do you find those? Plus have you found the right one(s)? The types of heuristics used can vary by expert, and of course should fit your type of game — so this is obviously important.

Also sometimes experts can be a bit too expert and miss stuff that might be a problem for novices. This is because as we become more experienced at something we no longer need to consciously consider everything that we perceive and do, whereas someone who is still learning is still thinking about what they are doing all the time. This is why generally if you want to see something done well you watch an expert, but if you want to learn how to do something it is often best to ask a novice.

Pros

Smaller number of people needed

Relatively fast turn around

Experts are expert

Cons

Where do you find experts?

Did you find the right one?

Experts can be too expert

Questionnaires & Surveys

I am sure you know what a questionnaire is, but do you know how to design and use one correctly? Mountains of books have been written on this, but hopefully I can make at least some important points clear.

First of all, when do you use questionnaires? Well, they are usually used to evaluate subjective views about your game, particularly value judgements. This may vary from specifically asking players about their favorite weapon to open-ended questions asking for general comments on the experience.

Questionnaires can be given to players during the game, which means the experience is fresh, but this risks interrupting the flow of the game (if possible, find natural down times to ask). They can also be used after a gameplay session is over. The big advantage of questionnaires is that they can be given to many people, and as such you can end up with lots of nice data to examine (in theory).

Before I go into the detail of constructing your own questionnaire, there are some pre-existing questionnaires out there aimed at evaluating the fun of gameplay experiences.

Examples of such questionnaire are the Game Experience Questionnaire (GEQ) for examining gameplay experiences and the affect grid [PDF link] or the manikin system [PDF link] for rating emotions. These pre-existing questionnaires can be great, because they are usually well-written and reliable. However, they also have a tendency to be more academic in nature, and care should also be taken that they fit your game, so modify them if necessary.

So how do you go about designing your own questionnaire? Here are four steps that I hope can help you.

Step 1. Work out what you want to know

As stated already, all of these methods require that you know what information you are after. But this is extra important when it comes to questionnaire design. You usually don’t get any chance to follow up on people’s answers, so you want them to be as clear as possible, and for the information you gain to be what you are after (and neither too little nor too much!)

So, brainstorm, make lists, do whatever is best for you in terms of getting down what you want to know. Then cut it down to only what you really, really need to know. Be focused!

A mistake that novice researchers often make is to ask for everything simply because the opportunity is there. However what this results in is a mess of data that will take forever to be analyzed, and may not produce a meaningful result. You don’t really want your questionnaire taking more than 15 to 20 minutes to answer (this is not a target, by the way, but a maximum).

Step 2. Design the content

The design part is the meat of the process and can be further broken down into a few things to consider.

Questions or statements? Do you want people to answer questions, or rate statements? This is pretty straightforward but still important. Basically, questions are good for gaining information, for example:

How challenging was the Horrible Bog Beast?

1 2 3 4 5 6 7

Very easy Very Hard

Questions can also be worded in the form of an instruction. For example, “Rank the levels you just played in order from 1-6, where 1 is the one you enjoyed the most, and 6 is the one you enjoyed the least.” It’s effectively just like asking a question about the ratings for each level individually.

On the other hand, getting people to rate statements is more typically used to assess value judgments or agreement with ideas, so an example would be something like:

The Horrible Bog Beast is an interesting enemy to encounter.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7

Strongly Agree Strongly Disagree

Either questions or statements are fine; however, use them where they are best, and don’t switch between the two types too often.

Language use. It is incredibly important that you use clear, everyday language. Avoid jargon. This is vital because you want to be sure that the people you are testing understand what you are asking. Many people will just answer anyway, even if they don’t understand a question (be honest — I am sure you have done it) and the data you get may not be useful at all. So be blunt, be direct, and ask for exactly what you want to know.

When you offer alternative answers to your questions (for example if they have to select from a list of consoles they own), these should be relatively exhaustive. So in other words there shouldn’t be any alternatives that you haven’t thought of. Adding an “other” where additional options can be filled in can help here, but it is best if this “other” option isn’t used too often.

You should also be careful not to ask what is essentially the same question, but in a different way. Remember the goal is to keep the number of questions down. Also avoid asking questions that are phrased negatively. So “I like the jumping mechanic” and a gradient from agree to disagree rather than “I don’t like the jumping mechanic”. In the case of negatively-phrased questions, people filling your questionnaire have to select “agree” to disagree, and “disagree” to agree. It seems silly, but this can confuse people.

Also avoid leading, double barreled, and loaded questions. A leading question is one where the person filling it in is lead or biased to give a certain answer, e.g. “This game was fun. How fun was it?” This example is, of course, over the top, but you would be surprised how often leading questions can slip into questionnaires, so just try and keep your wording direct, and neutral. Don’t assume. Ask!

Double (or multiple) barreled questions ask about more than one thing at a time. Here’s an example from outside the world of games — from a national referendum held in New Zealand:

“Should there be a reform of our justice system placing greater emphasis on the needs of victims, providing restitution and compensation for them and imposing minimum sentences and hard labour for all serious violent offences?” YES/NO

As you can see, there are at least six questions here; should there be a reform, should it place greater emphasis on the needs of victims, should it provide restitution and compensation, should it impose minimum sentences, should it impose hard labour, and should it be for all serious violent offences? But you only get to say yes or no once. As I say, this question was put to the whole of New Zealand, and really ruined my first ever experience of voting.

Loaded questions are ones that make moral judgments or make assumptions that are unfounded; an example of this type of question also comes from a New Zealand referendum where it was asked:

“Should a smack as part of good parental correction be a criminal offence in New Zealand?” YES/NO

This question is loaded in that it uses a moral term like “good”. It is also ill-defined, as it uses the term “good parental correction” (whatever that is), and finally it is misleading in that if you are anti-smacking you have to say yes (agree) and if you are pro-smacking you have to say no (disagree).

Closed or open? Questions can be either open, as in the player can say whatever they like, or closed, where there are only a few limited options to select.

Open questions allow for richer data to be collected, as they let players give as much feedback as they want. However they can also give as little as they want, and often without direction, the answers may be vague.

One way to get around this if you do use open questions is to make sure you have time to read them before the end of the session, in case you want to ask for clarification on any points people bring up. However this is difficult if the questionnaire is being given remotely, such as when it is being used via email or online.

Closed questions on the other hand let you have much tighter control on the answers your participants give, and come in several flavors (scales):

Dichotomous: This is for simple yes/no questions. So usually it used to collect stuff like yes/no, true/false. It is nice, direct, and precise. However, it is also not very data rich. So generally speaking such questions are used just to collect demographics, or when you really want to force a choice between two options.

A dichotomous choice in Diablo III

Continuous: This is where you ask people to give ratings along a continuum or sliding scale (like when you are doing face customization in games). The big advantage of a continuous scale is that it gives a lot of resolution. However that much resolution is hardly ever needed (is there really a difference between a rating of 96.43 and a 93.21?).

A (semi) continuous scale in Saints Row: The Third

Interval: This is probably the type of scale we are most familiar with. Here, you give a rating along some sort of scale with each step being separate/discrete from the other (rather than continuous).

This does lower the resolution of the scale when compared to a continuous scale, but it is much clearer in terms of allowing for comparison of results. In my opinion, a 1-7 scale is probably the best way to go (over say a 1-5, or something larger) as it allows for some good resolution, while not being too broad. Others may disagree

Several interval scales in Arkham Horror

If an interval scale is used, then it can also be broken down further into several types: numeric/categorical, Likert, or semantic.

A numeric scale is simple; it just asks for a number, and is used often to rank things.

Likert scales you have probably seen many, many times and are usually for when you want to see how much someone agrees or disagrees with a certain statement, e.g. 1-7 where 1 is strongly disagree and 7 is strongly agree

Semantic scales are when you want to simply ask for a rating related to something or a value judgment, e.g. 1-7 where 1 is poor and 7 is good.

Each of these types of scales can be used where necessary, although generally speaking, it is best not to mix scale types too much. Otherwise people filling in the questionnaire might get confused and provide a rating that they think is using an agree to disagree dimension but is actually asking for poor to good.

Finally, with interval scales, you can either make them unipolar, where you ask for varying levels of one variable e.g. 1-7 where 1 is not very exciting and 7 is very exciting, or they can be bipolar where you contrast two different variables, e.g. 1-7 where 1 is very boring and 7 is very exciting. Unipolar scales zoom in on one area a bit better, but bipolar scales give people filling in the questionnaire more room to express their opinions. As with before, try to not mix these styles up within the same questionnaire too often, or at all.

Step 3. Put it together

You have your questions, so now’s the time to put it together. First, work out what medium you are going to use. Will it be collected via a computer (say a through a web interface), or via paper? Collecting via a computer is preferable if possible as it means that there will be less data entry later on, however sometimes the portability and ease of paper can win out.

Give yourself plenty of time to do this, and if you are planning on using a computer-based survey, there are many companies online that offer this kind of service. In particular I hear that SurveyMonkey is a popular choice, although I have not used it myself.

You should next consider what order to put your questions in. Generally speaking I advise putting the easy questions at the start. This gets people rolling, and as long as your questionnaire isn’t too long, they should be more prepared to tackle the bigger questions you want to ask later.

Then try and cluster the remaining questions in a sensible fashion, such as by subject, or what they refer to within the game. Don’t ask a bunch of questions about the weapons, then move on to the boss, and then go back to the weapons.

Also check to see if answering some questions excludes other questions or could cause new questions to be asked later on. If so, make sure this occurs. In other words, if you ask “Do you own an Xbox” yes/no, make sure later on the people who answered “no” aren’t asked to list the top ten Xbox games that they own.

Step 4. Test it

No plan survives its first contact with the players, so first test your questionnaire yourself. If you are using a computer-based questionnaire, make sure the data that comes out the end looks okay. Give it to a few other people (preferably people who are not too familiar with the game, or are not designers) and ask them to fill it in (with you outside of the room so you can’t help them), and then ask for their comments on the clarity of the questions. Essentially, user test it, and then change anything that might be wrong (and then test again…) This is a great deal of work, I know, but once you have a good questionnaire, you can possibly use it again in the future (or at least cannibalize it for juicy parts).

Pros and Cons

There is much more that could be said, but perhaps this is already too much for a “primer” — so I will move on. The best thing about a questionnaire is that you are asking the same questions to everyone, so you get consistent quantifiable data that you can compare between people.

However they lack follow-up, in that you can’t ask people why they selected a certain rating, they are not objective, and you do need quite a few people if you want to draw completely solid conclusions from them. That said, even when testing with just a few people, providing a questionnaire can give you some ideas about what those individuals thought.

Pros

Consistent

Quantifiable

Relatively quick to administer

Can be used on a large scale

Cons

Can lack follow-up

Not objective

Really at their best with large sample sizes

It can take a while to put together a good questionnaire

Hopefully that is more than enough for this first article. While again this article is in no way comprehensive, I hope it has proven to be useful. In the upcoming part of this rough primer, I will be covering interviews, observational methods, game metrics and biometrics.

Finally, if you are interested in games user research or work in the area, then please consider checking out the IGDA Special Interest Group for Games User Research (GUR-SIG) on LinkedIn (just search for the group). It is a great place to get together and discuss GUR with others working in or around the industry.(source:GAMASUTRA)