细述游戏设计10大重要步骤及原则

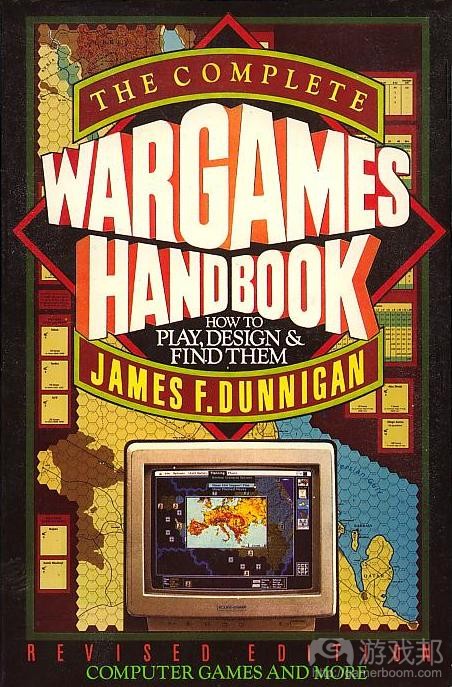

《The Complete Wargames Handbook》作者James F. Dunnigan(游戏邦注:他同时也是著名战争游戏设计师)将桌面战争游戏设计总结成10大步骤。我就其所述内容深入扩展以便进一步挖掘游戏设计理念。

设计游戏没有所谓的万能指南。但这里我要分享的是成功战争游戏均遵循的10大设计步骤。

1. 首先最重要的步骤是概念发展。也就是说你需在最初阶段确定你所要制作的内容。

这里高概念(High Concept)、吸引力(The Hook)和简要描述语(One-Sentence Marketing Description)均非常适用于定义游戏设计的目标。

然后你就逐步转移到定义“金字塔的底层”。在动工前把握设计包含哪些及未包含哪些内容。这能够有效避免出现“激进现实主义”:随着开发的进展,越来越多内容开始融入其中,设计所覆盖的范围因此越来越大。

若你在实施前清楚知晓界限所在,你就不会犯下一些错误,例如排除某些对设计而言非常有用和重要的内容,或囊括某些模糊设计焦点的内容。

不要偏离先前确定的简要描述语。所有内容都要重新回到游戏的原始高概念、吸引力和简要描述语,否则你就会陷入困境,制作出有违最初设想的作品。

2. 再来就是调查研究。你需要在概念发展阶段完成其中的部分内容。此时,你需尽力填补自己的知识缺口。

就制作战争游戏而言,调查研究非常重要。若你打算基于历史主题制作不那么“严肃”的游戏,那么调查研究能够有效帮你向忠实玩家灌输某些“教育价值”,但注意把握好度。例如,Sid Meier并不是很重视历史调查研究,而是选择基于常识设置游戏的“历史”元素,这样玩家就能够在开始游戏时“立即熟悉”自己的所见内容。

若你在虚构背景下制作游戏,那么此阶段的任务就是进行大量背景构思。事实上,你就是在给金字塔的底层奠定基础。

若你制作的是抽象或文字游戏,你也许会想要探究定义游戏设计“公差”的数学概率。

若你制作的是基于组件的游戏,你会想要斟酌特殊组件的材料,它们的价格和实用性。

3. 此步骤就是我所谓的“整合”:将所有研究资料和游戏机制知识整合进模型游戏。

无论模型是纸上游戏,还是首份完整设计文稿,这都是你设计和“组合”所有设计组件的阶段。此时你需要纵观全局,而非瞄准局部。

换而言之,这就是游戏设计的“大体解剖”。也就是说,你需确定游戏的大型机制如何进行组合和配合。

“总的来说,游戏的组件是什么?”“它们如何进行移动?”“它们如何互动?”“玩家如何同组件互动?”“游戏的目标是什么?”这些问题能够帮你定义和安排大型组件,这样你就会发现你的金字塔结构非常整齐和稳固。

4. 充实你的原型,创造类似于可玩游戏的内容(或者完整的游戏设计文件)。

完成将知识植入设计大型组件的大体解剖后,现在就得锁定细节任务,连接“神经节”,创造能够利用的内容。此时你的焦点就会从全局转移到局部。

此设计阶段将出现许多恼人的情况,所以请做好心理准备。有时基础设施(步骤3)的设置天衣无缝(步骤4),那就更容易实现预期目标。但更多时候,你会发现理论构思(步骤1-3)要比完成所有细节(步骤4)的实际操作简单得多。

在此阶段你需要左右脑并用因为解决方案源自其中。有时发挥左脑的严谨性,有助于避免设计出现漏洞。而某些时候,你需要用右脑的创意思维,以全新方式设计基础设施,创造新元素解决某设计问题。通常情况,我们完全能够结合两种方式消除设计缺陷,创造能够进行远程体验的内容(游戏邦注:这就是所谓的左右脑并用)。

需要强调的是:游戏设计师需要双脑并用;也就是所谓的“左右脑并用”。若你没有充分利用你的右脑,游戏设计就会在机制、创意和原创性上缺乏预期的魔力。若你左脑较弱,那么平衡、组织、编辑和表达设计方面就会出现问题。很多游戏设计师的大脑都是一强一弱,这也是他们选择同他人搭档的原因所在,以此弥补自己的不足。当你读到游戏设计工作人员名单时,你就会知道谁是设计团队的“创意”人士,谁负责将艺术图像转化成表达充分、具有可玩性的平衡游戏。

5. 准备游戏规则的初稿。很多人都忽略此步骤,倾向将规则记在自己的脑中,在后期时才进行记录。他们事后通常都会后悔。

在之前的步骤中,你也许已记录些许要点,让自己专注于预期目标,这是件好事。现在你需要将这些规则具体化,或者起草粗糙的游戏手册,这样你就能够向他人展示,他们就能够清楚把握你的游戏设计目标。也就是说,他们能够设想游戏的运作方式,及需采取什么行动让游戏运作。

6. 游戏开发是相对困难的步骤。这意味着你需要进行游戏测试,调整游戏内容,重新编写游戏规则,承受某些宁愿体验游戏而不愿参与制作,不懂得尊重设计师劳动成果之人的犀利批评。

游戏设计师需密切参与此步骤;这属于“亲自动手”操作。此时你会亲自同他人体验自己的游戏,回答团队成员有关设计的问题及他们的预期。你会听到很多“但你需考虑这点”、“若出现这种那种情况,你就会错过某些内容”的言论及其他你在组合基础设计时(步骤4)所忽视的漏洞。

你信任及共事的重要人士会首先查看被你视为珍宝的游戏作品,可能会将其视作胡乱拼凑的粗糙怪物。若你想要制作出更好的作品,你需忍受他们的“无情攻击”,并将其中的建设性批评铭记于心。

此步骤的目标是重新起草和撰写游戏的薄弱环节,为下个步骤作准备:

7. 我将此步骤称作“盲测”。此时你会将自己的实体模型和书面规则发给某个无需你在场就能够进行体验的人士。

就电脑游戏来说,这就类似于“向外部”发送测试版内容,让新眼光审视作品。

需从新测试者身上把握的最关键要素是他们在游戏中的“第一次经历”。他们是否能够轻松进入游戏?是否能够靠直觉感知?游戏的总体人机工程学是否协调,不会令人感到沮丧?他们是否能够在游戏要素中快速和轻松地找到问题的答案?换而言之,就是他们头几分钟体验是否愉快、趣味横生?若没有,这就是你所要修复的大问题。

在它们反复体验游戏后,你就会得到什么可行,什么不可行的反馈,二者均涉及游戏设计的大型组件及玩家遭遇的细节内容。在此过程的此阶段,我们很难做出重大调整,所以明智设计师需巧妙地将解决方案落实到所面临的真正问题。当你步入此阶段,最佳解决方案通常是那些包含最少工作量或变化的调整;进行巧妙调整或削减内容通常才是正确路线。

8. 编辑。此步骤出现在盲测结果呈现且植入手稿的时候。现在会有其他人接手手稿,进行编辑。这同时也意味着你需要试着基于所有调整和变更体验游戏,尽量找出其中缺陷。

创作者无法编辑自己的作品,游戏设计师亦是如此。此时无需忘却过去内容的新鲜眼光和思维能够比你更好地“完成”游戏。

我所说的无需忘却过去游戏版本是指那些只玩过游戏最终版本的新人。他们不知晓7个版本前游戏的运作情况。也就是说,他们无需通过“忘却”来体验游戏的最新版本。因此他们不会基于长期测试体验做出任何假设。这会让你的规则或游戏手册忠于最新版本,未融入任何之前版本的错误参照。

此时你所要做的就是参与最终测试,所做调整应是能够轻松融入游戏、旨在提高游戏平衡性的细微改变,同时检查所有内容,确保所有内容顺利运作。

9. 制作。若你即将发行游戏,就是处于制作阶段。此时很多事情都会出错。设计师需要设置规则,基于原型准备美工内容。此阶段存在很多潜在危险。

你需要承担很多校正工作。你无法做到万无一失,亲自检查制作的各个方面。你需要查看所有广告副本、包装样式、新闻发布内容及邮件谈话。若这是以书面形式,且涉及你的游戏,有机会的话,你最好还是参与其中,进行检查(游戏邦注:重要的是确保游戏在发行前做到尽善尽美)。

10. 反馈。若你打算设计更多作品,此步骤也非常重要。此时你能够系统地从玩家身上收集反馈信息,查看自己的优点和缺点所在。

这是非常沉重的担子,很多设计师会发现此时自己如履薄冰。记住在此阶段,你将获悉作品的优缺点。这些反馈信息其表达方式非常个人和主观。

游戏批评者的看法非常主观。这些不仅包括不分青红皂白的网民,也不局限于所谓的“正统”媒体批评者。应该还包括你最亲近的同事,最好的朋友,甚至是你的家人!别人批评你作品的感觉就像是所有你认识的人都在揍“你的孩子”,你会很想尖叫,“什么时候才会结束啊?”

但这永远都不会结束,除非你的作品完全淡出大众视线,但即便作品消失,批评声也不会完全终止。

所以你的内心一定要足够强大才行。批评者的口诛笔伐主要针对你的游戏设计,若你无法承受攻击,那这就可能是你的最后一个作品。接受这样的事实:不是所有人都会喜欢你的游戏,这些攻击性反馈信息是“整个开发过程的组成部分”。这是你自己的选择,而且你事先也已经知道会出现这种情况。

要学会淡然看待这些。从谩骂中提取有用信息,总结好的评价,然后进行反思。这些人很多只是“试着给予帮助”。记住在生活中,不要将原本只是出于愚昧的批评归结为恶意相向。关于设计师或作品的批评多数时候只是出于某人愚昧无知,而非有意针锋相对。(本文为游戏邦/gamerboom.com编译,拒绝任何不保留版权的转载,如需转载请联系:游戏邦)

Principles of Game Design

In his book The Complete Wargames Handbook (published by Morrow), author and legendary wargame designer James F. Dunnigan summed up board wargame design as a ten-step process. I’ve taken the liberty of expanding upon his ideas to broaden the subject to cover game design in general. Hopefully, you will find this a useful listing of one approach to the steps you need to take to design your own game. There are other approaches, and if you become a game designer as your ‘day job,’ you’ll be indoctrinated into their approach, I’m sure. If you become an ‘independent’ game designer, you’ll devise your own approach but should refer to these notes from a couple of ‘old hands’ as a useful reference of ideas so that your own approach doesn’t ‘leave out anything important’ in the process.

The sections in non-italic type are the words of Jim Dunnigan. My commentary follows in italic type. –Alan Emrich

10 Steps to Designing a Game

There are no ironclad, guaranteed (‘Follow these rules and you cannot fail’) guidelines for designing a game. I do have, however, 10 steps that are generally followed in successful [board] wargame designs. The number of steps has actually changed over the many years that I have been designing games. But, in essence, these 10 steps, albeit rearranged and renamed occasionally, have remained remarkably consistent.

1. The first, and most important step, is concept development. That is, you must determine at the very beginning what it is that you want to do.

This is where the High Concept, The Hook(s), and the One-Sentence Marketing Description all fit in to define the target you’re aiming for in your game design.

From those, you move on to defining “The Base of the Pyramid.” It is important to know before going any further what specific things (and what kinds of things) will be expressly included and excluded from the design. This will go a long way toward avoiding the problem of “Kitchen Sink-itus” where the design keeps growing and growing as more stuff gets added over the course of the game’s development cycle.

If you clearly know where the boundaries are before you get the ball rolling, you won’t make the mistake of excluding something philosophically proper and important to your design or including something that blurs the focus of the design (which threatens every single game design).

And never, never deviate from the One-Sentence Marketing Description that has been previously decided upon (unless you get everyone on board to change what kind of game to make). Everything has to connect back to the game’s original High Concept, Hook(s), and One-Sentence Marketing Description or else you’re heading off into the weeds and making a different game than you knew you needed to when you started. (Don’t go there.)

2. Next comes research. You will probably have done a little of this during the concept development stage. At this point, you must fill in as many of the gaps in your knowledge as you can.

When making wargames, research is very important and thus very high on Jim’s list. If you’re making a less ‘serious’ game on a historical subject, research is important if you’re trying to sneak in some “education value” to the unsuspecting player, but be careful not to overdo it. Sid Meier, for instance, does his historical research last, opting to have the ‘history’ elements of his games based upon common knowledge (and misperceptions) so that players are ‘instantly familiar’ with what they see when they start playing that game.

If you’re making a game in a fictional setting, then this stage is for doing as much conceptualizing of that setting as possible. In effect, you’re starting to lay the foundation of The Base of the Pyramid.

If you’re making an abstract or word game, you might want to consider the mathematical probabilities that will define the ‘tolerance’ of your game design (i.e., how many pieces there will be, how many letter C’s in the Scrabble bag, etc.).

If you’re making a component-based game, you might want to consider materials for those special components, their prices and availability.

3. This step is what I call “integration.” It is where you take all of the research material and your knowledge of game mechanics and integrate it into a prototype game.

Whether your prototype is a paper game or the first complete pass through writing a design document, this is where you have to design and ‘fit’ the big pieces of the design plumbing together (without worrying too much about sealing the leaks). This stage is where you’re focused on the forest, and not the trees.

Let me put it another way; this is the Gross Anatomy part of game design. That is, you must start nailing down how the larger systems of how the game will fit and work together (but not sweat the minutiae of how every synapse will connect).

Answering questions like, “What, in general, will the pieces in this game be?” “How will they move?” “How will they interact with each other?” “How will the player(s) interact with the pieces?” “What’s the object of this game?” will help you define and arrange the Big Pieces together such that you’re satisfied that your Pyramid’s structure is straight and sound.

4. Now, you flesh out your prototype and come up with, in effect, something that looks remarkably close to a playable game [or a complete design document, for computer games].

Satisfied with the Gross Anatomy of integrating your knowledge into the big pieces of your design, now it’s time to focus on the detail work, connect the synapses, and create something usable. This is where your focus zooms in from the forest (which you arranged in the previous step) to the trees.

There will be a lot of agonizing at this stage of the design, so expect it. Sometimes, the plumbing (from step 3) fits without a leak (in step 4) and you’re golden. More often, though, you’ll find that the design was much easier to dream up in theory (steps 1 through 3) than to execute in practice by completing all the details (step 4).

This step is where you really have be ‘both-brained’ (as opposed to just left-brained or right-brained) because solutions come from both sides of your brain. Sometimes, working the formulas will provide the right sealant to stop a leak in the design [using your left brain]. Other times, you’ll need to envision the pipes in a whole new way and innovate something fresh to get around a design problem [using your right brain]. Usually, it will take a combination of approaches to iron out the kinks in the design and come up with something that’s remotely playable (which is what I call being ‘both brained’).

Let me emphasize that: being a game designer means being ambi-brain-trous (as opposed to ambidextrous); that is, being ‘both brained.’ If you don’t have sufficient chops in your right brain, your game designs will lack a certain expected magic in cleverness, creativity, and originality. If you’re left brain is a weak link, then balancing, organizing, codifying, and clearly communicating your design will be problems. Many game designers are strong on one side and weak on the other, which is why they pair up with others who compensate for their weak side. When you read the game design credits for games, you’ll learn to see who was the ‘creative’ person on the design team, and who did all of the grunt work to turn that artistic vision into a well communicated, playable, and balanced game.

5. Prepare a first draft of the rules. Many people overlook this step, preferring to keep the rules in their heads for a while longer. They usually come to regret this.

During the previous steps, you’ve probably made some notes to yourself already to help you stay focused on what you’re trying to achieve, and that’s a good thing. Now you need to flesh out the rules or draft a game manual to at least a minimal level where you can hand it off to someone and they’d have a good idea what you’re trying to do with this game design. That is, they can envision how the game will work and what they need to do to make it work.

6. This is one of the more difficult steps: game development. This means playtesting and changing the game and rewriting the rules and taking a lot of abuse from people who would rather play games than work on them and don’t appreciate all the problems the poor designer has in getting anything done.

You, the game designer, stay very involved in this step; it is a ‘hands on’ operation. This is where you play your own game with others and answer team member’s questions about your design and what they’re expected to do. You’ll hear a lot of “You needed to think this though” and “You left out what happens if this and that and then the other occurs” and all about other leaks that you didn’t catch while fixing the plumbing in Step 4.

Important people that you trust and are working with on this game are getting their first look at “your baby” and seeing it as the crude Frankenstein monster that you’ve been able to cobble together thus far. You need to be able to get past their abuse and take their criticisms to heart if it will make a better game. (Hey, it’s not like you’ve got some monopoly on brilliant ideas, bucko.)

The goal of this step is to redraft and rewrite over the game’s weak spots and prepare for the next step:

7. I call this step “blind testing.” This is where you take your physical prototype and your written rules and send them out to somebody who can play the game without your presence. This is often very revealing.

For computer games, this is the same as send a beta copy ‘out of house’ and having some fresh eyes see the game for the first time.

The most critical thing to learn from new testers is their all-important ‘first experience’ with the game. Could they get into it easily? Was it intuitive? Where the general ergonomics friendly and not frustrating? Could they find the answers to their questions quickly and easily within the game’s components? In other words, where their first few minutes (say, up to a half-hour) with the game pleasant and enjoyable? If not, you’ve got a big problem to fix right there!

After they’re used to the game, you’ll get feedback about what’s working and what’s not, both about the big pieces of the game’s design, as well as the minutiae players encounter. It will be difficult to make major changes at this point in the process, so a good designer has to be clever in applying solutions to real problems that are brought to his or her attention. When you reach this step, the best solutions are usually those that involve the least amount of work or changes; a clever tweak or cutting something out entirely is generally the right way to go.

8. Editing. This step occurs when all of your blind testing results have come back and have been integrated into the manuscript. Somebody else should now take over the manuscript and edit it. This also means trying to play the game with all of the final corrections and changes in an effort to smoke out as many gremlins as possible.

It’s nearly impossible for writers to edit their own writing, and so it is with game designers editing their own games. At this point, a fresh pair of eyes and a mind that doesn’t have anything to forget about past iterations the game design will do a much better job on ‘finishing’ your game than you will.

What I mean by not having anything to forget about past version of the game design is that a new person will have never played any but the final version of it. They don’t remember how some aspect worked six versions ago (and won’t be confused by having a knowledge of any past iterations of the game). That is, they have nothing to ‘unlearn’ to play the latest version of the game. Thus, they won’t make any assumptions based upon long playtesting experience (like you will). This will make your rules or game manual true to the latest (‘final’) version of the game and not include any false reference to previous versions.

What you need to do at this time is to join in the final playtesting, not make any changes greater than a subtle tweak that is easily incorporated and improves the balance of the game, and proof-read everything to make sure everyone’s got it right.

9. Production. If you are going to publish the game, this is the production step. This is where a million things can go wrong. Rules have to be laid out (and things can get scrambled there). The artwork has to be prepared from your prototype (and is subject to untold misinterpretations). There is a lot of potential danger in this stage.

And a lot more proofreading for you to do. You can’t do enough proofing and hands-on inspection of every aspect of production. You should read all the ad copy, the box copy, the press releases, email interviews… everything that you can. If it is in writing and about your game, you’d better jolly well interject yourself into the process and proofread it if you have the opportunity. It’s important that nothing is said about the game that it doesn’t deliver.

10. Feedback. This step is also extremely critical if you are going to design more games. This is the step where you systematically collect feedback from those who play your game to see where you went right and where you went wrong.

This is a heavy burden where more than one game designer has found himself or herself martyred at the stake. Remember, this is a step where the game is analyzed to tell you what you did right or wrong. It is very personal that way.

Critics of the game can get quite personal (abusively so). These are not just indiscriminate flaming idiots on the internet Newsgroups, nor even the critics of the so-called ‘legitimate’ hobby press. No, these will include your closest coworkers, your best friends, even your family! When there’s something bad to be said about your game, it’s going to seem like everyone you ever knew is beating up on ‘your baby’ and you’ll want to scream, “When will it all end?”

But it never ends until your game has been retired to obscurity, and even then it only dies down and never quite ends.

So you will need very thick emotional armor. The slings and arrows of outrageous fortune are all targeted at your game design (and sometimes you personally), and if you can’t take the abuse, then this will be the last game you ever design! Take solace in the fact that not everyone is going to like you or your game, and that this kind of hurtful (and occasionally helpful) feedback is all ‘part of the process.’ This is what you signed up for, and you were warned (because I just warned you).

Learn to take it all in stride. Separate the useful feedback from the invective and file the good criticism away and reflect upon it. Many of these people ‘are only trying to help’ (even though you many find it personally hurtful). Remember, in all things in life, never ascribe to malice what can just as easily be assigned to stupidity. Most of the hurtful things you’ll hear about you or your game are being said stupidly by someone who really doesn’t think they’re being mean.(Source:alanemrich)

上一篇:阐述游戏设计师的主要工作职责

闽公网安备35020302001549号

闽公网安备35020302001549号