社交游戏的反社交机制:隔三差五请求帮助

作者:Leigh Alexander

Facebook游戏备受轻视,而几年前此矛头瞄准的是所谓的“休闲”游戏。近来,扎根游戏领域的人士都认为无需迁就休闲内容的内在质量——甚至连我们都开始觉得“休闲”一词已和现代社会无关。

“社交”是否会步此后尘?鉴于热门核心作品社交工具和高级社交功能的层出不穷,这似乎颇有可能。当所有内容都在线呈现,要求多人功能。以“社交”定义游戏意义何在?

但目前,被称作“社交游戏”的内容多半指Facebook游戏——而它们大多被当作低文化内涵的内容。游戏至多被视作肤浅而简单的正派娱乐活动,而最糟则被视为欺骗、狡诈,和电脑病毒无异的游戏内容。

但当EA宣布将倍受欢迎的《模拟人生》移至Facebook平台时,似乎又令人觉得社交游戏还是存在些许希望。

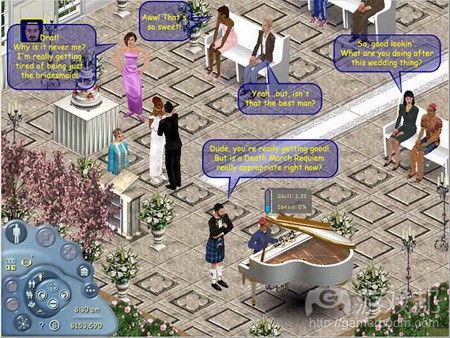

这是款备受广泛用户追捧的热门作品,其内容和平台非常契合:《模拟人生》依赖众多Facebook游戏的精髓元素——表达个人身份;拜访其他角色,进行互动;管理日常任务;通过细心维护赚取奖励。

凭借共同元素和广泛吸引力,《The Sims Social》有望稍稍提高Facebook游戏的地位——确实如此,游戏通过手眼协调模式瞄准更微妙、更难界定的用户体验元素,致使内容更受欢迎,更完善(游戏邦注:即便这些元素无法立即获得病毒式传播)。

这能够带动玩家更多好友参与游戏:这是新款备受欢迎的游戏内容,与《FarmVille》之类蒙受污名的游戏截然不同。

但EA的这款Facebook作品《The Sims Social》似乎大量借鉴Zynga作品,而Zynga作品是Facebook游戏的污名之源。从某种程度看,这些都是该领域领袖建立的最佳范例:Zynga给予所有活动奖励,分散各处供玩家点击(呈现极具诱惑的“弹出内容”,令玩家不知不觉受其吸引),这极富吸引力,《Sims Social》亦采用此策略。

“能量”原则亦是如此,这用于限制玩家每游戏回合的活动数量。其构思是,因需管理时间和资源(从而换得持续趣味体验)而倍感沮丧的玩家更愿意通过刺激性通知利用好友,或者购买积分来减少受挫感。

但遗憾的是,《The Sims Social》是模仿Zynga既有游戏中最糟糕的特性设计而成——虽然它完全没有必要这么做。

Facebook一大普遍社交机制是创造多组成要素的任务,要求好友共同参与完成各步骤。例如,若玩家想要城市中的某种建筑,或房内装饰道具,她需向好友索要道具,零件或劳动。这些通常不依赖实际存储;无论好友是否“拥有”所说道具,其只需接受,同意好友“帮助”请求。这个过程所需的并非真正物品,而是互动。

这造就此情形:很多游戏目标(游戏邦注:通常是那些标有“钥匙”符号的内容)若未通过发送通知给好友或发布广告式墙报告知所需物品就无法实现。通常随着游戏的进展,依靠帮助实现的成就和目标会越来越多。此目的是促使玩家保持依赖关系,借助一方促使另一方保持活跃。玩家曾投入大把时间关注游戏内容,但待新鲜感消失后便不再如此。

这些游戏的设计师也许会称,标准“请求”机制促使游戏更具“社交性”,鼓励玩家共同体验,但它们某种程度上也限制了社交互动。随着旨在帮助完成重要目标的墙报和通知消息数量的增加,任何有社交意识的玩家都会开始留意所发出的请求数量。有些游戏会限制玩家每天向好友发出的请求数量,而非阻止“垃圾信息”的发送,这反而会促使发送数量的增加。

这是因为玩家通常会很自然地向常给他们发消息的好友发送信息——但当那些好友已全都发过,游戏还继续要求他们进行索要资源,玩家会发现自己也开始向不确定是否会领会或回复的好友发消息。

最终结果是负强化。为得以在游戏中前进,玩家需发布自己的简单请求,最终需借助那些不确定是否会同样投入的好友。所以仅让玩家同少量一样活跃的好友保持联系会更好;每天发送请求确实有些令人尴尬。

Zynga游戏更令人为难——幼稚动画艺术及《Cityville》要求的基本任务都令人有些尴尬。你能想象进入成人Facebook页面,发现众多有关好友需要Fairy Wands(以便在农场创造奇迹)的帖子?备受尊敬的同事需要更多贝壳来完成他的水族馆!令人钦佩的雇主帮助臭鼬恢复其臭味!前途光明的合伙人有额外肥料可供分享!!这是真的?

当人们称Facebook游戏并非真正具有社交性时,他们所指的就是这些反社会的机制。这些机制忽视粘性的重要性,阻止通过体验深入交流。但《The Sims Social》完全无需借助这些元素;毕竟拜访好友家园是原生游戏的核心机制。创造自己的小人及其小生活的一半乐趣在于他们交流和分享的对象(游戏邦注:通过滑稽熟悉头像同好友共同体验本身就非常有趣)。

由于玩家在《The Sims Social》进行的所有活动都会带来奖励,他们似乎已倍受鼓舞,愿意邀请好友,寻找邻居,尽可能进行互动。即便通过墙报分享《Sims》趣事都要比仅宣布你有Mystery Eggs供应有趣。游戏似乎不该迫使玩家在个人墙面宣传简单物品或向好友发送通知。

玩家通过社交活动赚取积分,然后用它们购买房屋装饰道具是种有趣联系。然而,就像《The Sims Social》以前的所有恼人尴尬作品一样,玩家每次想要添加房间或购买某日常道具都需请求帮助,这在此类游戏中似乎有些违反逻辑。

若Facebook游戏要摆脱其污名,就需停止迫使玩家公开请求。在最初问世时,《The Sims Social》相比其他内容似乎有望充满趣味,引人入胜,真正融入社交性。但借鉴其他作品,引入接连涌现的“帮助”内容似乎不是明智之举。(本文为游戏邦/gamerboom.com编译,如需转载请联系:游戏邦)

Analysis: Anti-Social Game Design And The Sims Social

by Leigh Alexander

[Some "best practices" are undermining the evolution of Facebook game design -- Gamasutra editor-at-large Leigh Alexander looks at the worst carryover adopted in The Sims Social.]

Games on Facebook are often subject to a breed of blanket disdain, a sort of universal condescension which was several years ago reserved for so-called “casual” games. These days, people closely entrenched in the gaming universe generally agree there’s no inherent quality compromise necessary in the casual space — most of us even feel that “casual” isn’t a relevant term anymore in the modern landscape.

Will the word “social” follow the same arc? It seems likely, given the explosion of networking tools and advanced social features around popular core franchises. When everything’s online and requires multiplayer functionality, what does “social” even mean when used to qualify games?

For the moment, though, games referred to as “social games” are mostly Facebook titles — and for the most part, they sit largely in a cultural ghetto. At best, they’re perceived to be too shallow and simple to be respectable entertainment, and at worst, they can be seen as deceptive, insidious, not much better than computer viruses.

But when Electronic Arts announced it would bring an edition of its beloved The Sims brand to Facebook, it seemed to suggest some promise for social games.

Here was a popular brand with a history of respect among an unusually wide audience, and moreover, it appeared a perfect fit: The Sims as a game relies on a number of traits quintessential to Facebook gaming: Expressing individual identity, visiting and socializing with other characters, managing daily tasks and earning rewards for attentive upkeep.

Armed with those common factors and with its proven appeal, The Sims Social should be expected to raise the Facebook gaming bar at least a little — and it does, clearly developed with a hand and eye toward subtle, tough-to-define elements of user experience that feel more welcoming, more polished, even if (gasp!) those elements appear unlikely to immediately affect virality.

And it helps that more of one’s friends are likely to be attracted to the game: It’s new and it’s a well-liked brand, versus if you’re into FarmVille or something that carries a higher degree of negative stigma.

But EA’s The Sims Social on Facebook seems to have taken a surprising number of design lessons from Zynga, the mother of negative stigma on Facebook. To some extent it’s all best practices as established by the market leader: Zynga’s shown that having rewards springing out of every action, scattering everywhere to be clicked — an alluring “pop” that draws players’ attention even in spite of themselves — is strangely compelling, and Sims Social uses this tactic.

So is the “energy” principle, used to limit the amount of actions a player can accomplish in one play session. It seems the thinking is that a user frustrated by the need to manage time and resources in order to keep having fun would be more willing to impose on friends with irritant notifications, or to buy points, to alleviate the frustration.

But unfortunately, The Sims Social takes the absolute worst trait of Zynga’s established games and emulates it — even though it’s not obvious that it needs to.

One of the common social mechanics on Facebook is to create tasks that have multiple parts, and require participation from friends to complete each step. For example, if a player wants a certain kind of building in their city, or decorative item in their home, a player will have to ask friends for items, parts or labor. These generally don’t rely on actual inventory; whether a friend “has” said item or not, they need only to receive and accept a “help” request from their friend in order to complete it. What’s required isn’t actually an object, it’s an interaction.

This creates conditions where many game objectives — often those framed as “key” — aren’t achievable without sending notifications to friends or making advertisement-style wall posts about what they need. And generally, as a game progresses, achievements and objectives that rely on asking for help multiply. This seems designed to keep players reliant on one another, employing them to keep one another active, once players have invested enough time to care about the game world but after the novelty has begun fading.

Designers of these games may argue that the standard “ask for help” mechanic helps games be more “social,” encouraging people to play together, but they actually limit socialization somewhat. Because generally the number of wall posts and notification messages required to achieve important objectives increases, any socially-conscious player will begin to become mindful of the number of requests they’re sending. Some games limit the number of requests you can send to a single person per day, but rather than preventing the types of missives that could be perceived as “spam”, it probably increases them.

This is because players generally feel comfortable messaging others who also message them often — but when those are exhausted and the game still forces them to ask for resources, players often find themselves sending notifications to people they aren’t so sure will appreciate or answer them.

The end result is negative reinforcement. In order to progress in the game, players need to shout simplistic requests into the aether, and eventually will need to impose on those who aren’t guaranteed to be equally invested in progressing. It’s better just to stick with the small handful of players who are equally as active as you; it feels embarrassing, to be that person sending daily requests.

And in the case of Zynga’s games, it’s even more embarrassing — the child-like, cartoonish art and the basic tasks demanded by Cityville can make things downright awkward. Can you imagine going to an adult’s Facebook page and seeing post after post about how your friend needs extra Fairy Wands to make magic on their farm? Respected Colleague needs more seashells to complete his aquarium! Admired Employer is helping a skunk get his stink back! Prospective Partner has extra fertilizer to share!! I mean, honestly?

When people say that Facebook games aren’t actually social, these antisocial mechanics are precisely what they’re referring to. They trivialize engagement and discourage further networking through play. But The Sims Social shouldn’t need to rely on them; after all, visiting friends’ houses is core to the mechanics of the original game. Half the fun of making your own little person and building them a little life is who they get to talk to and share it with — the idea of being able to play with your friends using comical, familiar fantasy avatars is compelling enough by itself.

And since every action one can undertake in The Sims Social yields a reward, it seems possible that players will be already encouraged to invite their friends, seek out neighbors and interact with as many people as possible. Even sharing, via Wall posts, funny occurrences among Sims in the game seems a lot more interesting than just declaring that you have Mystery Eggs to offer. It doesn’t seem that the game should have to force players to advertise for simple objects on their personal walls or to send notifications to their friends.

That players can earn points by socializing and then later use them to buy decorations to their houses (versus real money transaction, or even versus in-game currency) is a cool touch. And yet, like in all The Sims Social’s irritating, embarrassing predecessors, that players have to solicit assistance every time they want to add a room or purchase certain types of household items seems like backward logic in a game like this one.

If gaming on Facebook is ever going to escape its cumbersome reputation, it needs to stop forcing players to beg in public. At early blush, The Sims Social seems promisingly fun, exciting and actually social relative to other choices. But the multi-stage “help” projects are not a welcome carryover from other games.(Source:gamasutra)

闽公网安备35020302001549号

闽公网安备35020302001549号