阐述社交游戏与街机游戏的相同点

作者:Brice Morrison

游戏设计会让玩家沉迷,难度加深会导致他们投入更多金钱,在前30秒内提供大额奖励从心理上吸引玩家,展示朋友及其他玩家的行为保持玩家的竞争性。

你能猜到我说的是哪种游戏吗?

假如你现在在线的话,可能会想到我在说的是Facebook游戏。这个平台席卷全球,现在每月都有数亿人在玩上面的游戏。与以往相比,更多人通过游戏互动。事实上,在Facebook上玩游戏的人数比任何时代玩主机游戏的玩家都要多。

但是,这种改革同时伴随着批判。许多游戏开发者,尤其是那些成长中有主机游戏伴随而且习惯于长期游戏时间的人,完全否定社交游戏。有些人根本不能理解。为何有人会为一匹虚拟的马花那么多的钱?这是种毫无意义的行为。

作为前社交游戏设计师和游戏狂热分子,我不认同这些人草率否定整个题材。这个话题我很关心。因此,我打算编撰这篇文章分析今日Facebook的族谱,其渊源可追溯至当年的自助街机游戏。

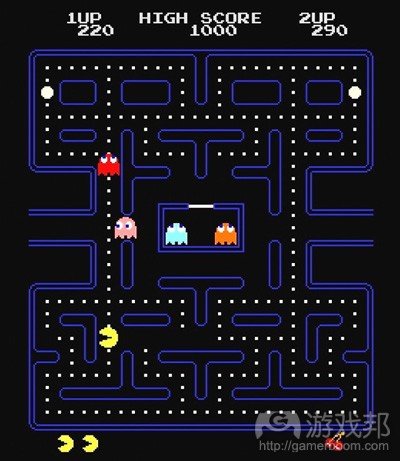

以上所提到的所有游戏设计也都是街机游戏的特征,包括《大金刚》、《吃豆人》和《杀虫大战》。

经济利益驱动的游戏设计

佐治亚州技术教授Ian Bogost颇得我尊敬,他在SF Weekly文章《FarmVillains》中表示,Zynga的游戏好似掠夺性开采。他们并不关心这种形式或体验的寿命,这种态度类似于那些石油或医药公司。这些游戏并不关注艺术性和娱乐。

我认为,这种说法为许多游戏开发者所认同,即Facebook游戏完全由经济利益驱动。游戏构建目标不是为了让玩家从中获得乐趣,而是想将利益最大化。设计师讨论的全是如何设计玩家愿意购买的新地产,而不是那些有趣的功能。他们讨论的是那些能产生盈利的特征。许多人认为这是错误的做法,这种话题也让许多开发者感到很不舒坦。

但此类注重盈利的游戏设计讨论并不只在Facebook游戏中出现,街机游戏也是如此。如果你制造的游戏太难,那么玩家会丧失信心,也就不会再玩了。但是,如果你将游戏设计得过于简单,玩家也就无需花上很多的金钱。因而,技巧就在于如何制作出吸引玩家且让他们认为自己下次尝试能做得更好的游戏。

在许多街机游戏中,玩家再次投入硬币时游戏重新开始。但《雷电》或《合金弹头》之类的游戏允许玩家用更多硬币来继续游戏,即花钱购买更多角色生命值。你既可以凭借技术也可以凭借金钱来实现某个目标,这与今日许多Facebook游戏无异。游戏设计会直接影响到公司获得的盈利,无论公司接下来选择继续运营游戏还是制作出系列游戏。

如果将某个BOSS设计得过于简单,就失去了许多从玩家手中赚取硬币的机会。

因而,经济利益驱动的游戏设计想法并不新颖,其深深扎根于街机游戏和其他我在此文中未曾提及的游戏形式中。事实上,不只街机游戏以盈利为目标,主机游戏也是如此。不同之处只在于过程,因为后者的运营是与游戏设计同期进行的。15年来,自首台NES到PS3,游戏行业的现状是开发者和运营人员各司其职。开发者只关注游戏的趣味性,除了尽力向玩家呈现绝佳游戏体验外无需思考其他内容。同时,营销人员和MBA们正倾尽全力销售产品,与零售商交谈,获取他们的订单,压低价格与竞争者对抗。

所有的运营事务或者有关金钱的事情并非游戏开发者真正感兴趣的东西。因而,当开发者们被要求将运营融入到游戏设计中,可以想象对其心理的冲击力有多大。而以上正是许多Facebook游戏身上发生的事情。但我的观点是这不仅存在于Facebook,上世纪80年代的街机游戏也是如此。

即时满足感和沉迷性

在Facebook流行游戏中,玩家升至第二级所需的时间不到3分钟。处处都可以获得经验值和钱币,他们装载游戏后发现到处都是梦幻般的物品。许多玩家只做出几项行为,还没明白过来就发现自己已经升到了第二级。

投币街机游戏的设计风格也是如此。只要玩家投入硬币,瞬时就能体验到其中的乐趣。他们很快便会熟悉掌握控制,数秒钟之内便开始获得分数。摘到樱桃或扔下炸弹,游戏便立即奖励玩家10分、100分甚至1000分。不到1分钟的时间内,他们便可以获得数万分,而且分数还在不断增加。游戏继续进行,玩家对他们获得的东西感觉异常良好。

这些游戏的设计意图是相同的,在尽量短的时间内让玩家感觉他们完成某些事情,这样他们才能为游戏体验所吸引。无论是在《Mafia Wars》中点击“做任务”,还是在《大金刚》中跃过油桶,玩家都感觉良好,觉得自己正向更高分迈进。

友善的竞争

比玩游戏更有趣的是什么呢?当然是和朋友一起玩游戏。友情、对手以及现实世界中的竞争让游戏更加有趣和令人兴奋。竞标赛、公会甚至是周四晚上的扑克游戏都会让玩家聚集起来共同享受乐趣。因而,将好友和他人纳入游戏机制中以加深玩家体验是种很有意义的做法。

我们都行业内熟悉Facebook游戏的病毒性机制,无论我们是否对此表示认同。游戏不时传达“与好友共享钱币和经验值!”、“有只牛在你的农场里来回游荡,你要帮它找个家吗?”、“要建起这座商店,需要让好友赠送你5个螺栓。”这类的信息。没有玩家会讨厌看到这些,这也是为何Facebook制定游戏信息只向那些同样玩游戏的用户展示的原因所在。玩家喜欢听到好友在游戏中做什么的信息。如果看到“James刚刚抢劫了你的工厂,快去把东西抢回来!”这类信息,我相信没有人不会选择回到游戏中。

街机游戏有着类似但技术相对落后的功能,即高分排行榜。几乎每款游戏都允许玩家在游戏结束后输入自己名字的大写首字母,将分数记录在高分榜上。他们可以看到与其他玩这台街机的玩家想比自己的位置如何。

所设计的这些特征仍旨在让用户返回游戏。和Facebook一样,这种方法能产生社群感,是一种围绕游戏整体(游戏邦注:而不是单一游戏过程)来构建趣味性的强大方式。这些设计的存在有两个目的:让玩家花更多硬币并且为人们提供更多乐趣和更大的挑战性。

外界反应强烈的原因

Facebook游戏同我们所钟爱的投币街机游戏有诸多相似之处。我的观点是,许多所谓的“邪恶”Facebook游戏并非现在这个时代特有的东西,它们有着悠久的历史。

那么为何外界对这些游戏的反响如此强烈呢?为何我们都把枪口对准Facebook游戏?这让我回想起游戏行业数年前对Wii的反对之声。当Wii面世之时,玩家接触到许多新类型游戏。当时他们可能觉得《Wii Sports》是适合自己母亲甚至祖母的游戏,这类垃圾作品根本不能算作是真正的游戏。

这种情况听起来和现在很像,不是吗?

Susan Douglas曾批评《Where the Girls Are》的作者在大众媒体中讨论同类现象。此类的公开反对与Facebook游戏和Wii的处境类似,当成功产品面世时经常会遇到这种情况。但人们对其并不理解,而且这个产品产生数百万美元盈利,他们就变会变得愤怒。

尽管我们已经指出投币街机游戏和Facebook游戏有众多共同点,但两者间最大的差异是目标用户不同。许多Facebook游戏并非以硬核游戏玩家为受众。《光晕》适合此类人群,《Sorority Life》并不是如此。因而,当我们寻找理由来解释为何这些游戏很糟糕,我们得出的结论是“它们是利益驱动而制成的游戏”或“它们的目标是让玩家沉迷其中”,完全忽略了伴随我们成长的游戏性质与之相同。唯一不同的是,街机游戏是适合硬核玩家的游戏。

我们正迅速步入这样的游戏世界,全球人人都在玩游戏。我指的确实是每个人。每个电视节目也不是所有人都喜欢,因而自然游戏行业也是众口难调。尽管这些差异化令我们倍感失望,或许会导致我们提出质疑或批判,但最终结果依然是会出现某些我们不喜欢的游戏。

但是如果能让全世界人民都玩上游戏,即便是那些我可能无法理解的游戏,这也足以让我感到欣慰。

游戏邦注:本文发稿于2010年12月17日,所涉时间、事件和数据均以此为准。(本文为游戏邦/gamerboom.com编译,如需转载请联系:游戏邦)

Meet Facebook Games’ Ancestor: Coin-Op Arcades

Brice Morrison

Game designs built to keep players addicted. Perfectly tuned difficulty to compel them to cough up more real-world cash. Giving lavish rewards within the first 30 seconds to psychologically hook players. Showing activity of friends and other players to keep competitive juices flowing.

Can you guess what genre of games I’m talking about?

If you live in the present, which I assume you do, then you would probably think that I’m talking about Facebook games. The platform has taken the world by storm and now with over 200 million people playing them every month, more humans are interacting with games than ever before. In fact, there are more people playing games on Facebook than on every current generation console combined.

This movement hasn’t come without its critics, however. Many game developers, particularly those who grew up in the console generation and are well accustomed to their 3 hour play sessions and 50-hour intensive titles, absolutely despise social games. Some of us just don’t understand it. Why would someone spend extra money on a virtual horse that doesn’t do anything except animate? It makes no sense.

As a former social game designer as well as retro game enthusiast, I will not stand for such cursory dismissal of an entire genre. This is a topic I care deeply about.

So at the risk of being a little too combative, it pleases me to write an analysis of the family tree of today’s Facebook games, all the way back to the titles that introduced many of today’s game development generation to games in the first place: Coin-Op Arcade Games.

That’s right. All of the game design aspects mentioned at the top of this article apply to coin-op games as well. Donkey Kong, Pac-Man, Millipede, you name it. But don’t take my word for it. Let’s look at the facts.

Financially-Driven Game Design

Ian Bogost, a Georgia Tech professor who I respect a great deal, was quoted in the SF Weekly article “FarmVillains” saying that Zynga’s games are “like strip-mining. They don’t really care about the longevity of the form or the experience. … That sort of attitude is the sort of thing you usually hear about from oil companies or pharmaceuticals. You don’t really hear about it in arts and entertainment.”

This quote echoes how I think a lot of game developers feel, that Facebook games are all driven by financial incentive. That they aren’t built for player to have fun, they are crafted and tuned in order to maximize profit. When the designers sit down with their whiteboards to talk about the new homesteads players can purchase, they aren’t discussing what features they think would be fun. They are discussing what features they think will generate revenue. And this is wrong. It’s a conversation that makes a lot of us developers uncomfortable.

But these kinds of revenue-combined-with-game-design discussions weren’t unique to just Facebook games. Coin-Op Arcades had them too. If you created a game that was too difficult, then players would put in their quarter, lose, and quit playing. But if you made it too easy, then they would keep playing for hours, edging out other kids who had their own quarters to spend. Thus, the trick, and the pattern learned by some of the beloved games of that generation, was to make a game that got you hooked and made you think you could do better on the second go around.

Many games only allowed players to start and restart with each quarter. But other coin op games, like Raiden Fighters or Metal Slug, allowed players to go further in the game by using more quarters, plunking them in literally for extra lives. You could get there by skill or by paying…not unlike many Facebook games today. And the actual design of the game had a direct effect on the amount of revenue the company would make, whether they would stay in business, and whether they would make another game in the franchise.

Make the second tank boss too easy? You’ve just missed out on a lot of quarters and a lot of revenue from players purchasing more lives.

So the idea of financially-driven game design is not new. It has its roots in Coin-Op games and other models that I won’t get into here. What’s different then is not that the games have a financial incentive, because even console titles have a financial incentive. The difference is in the process, that the business model is “mixed up with” the game design model. For a good 15 years or so, from the first Nintendo Entertainment System to the Playstation 3, the game industry was able to exist with developers in one room and business people in the other room. The developers would just focus on the “fun”, with no other thought than delivering a great play experience. Meanwhile down the hall, the marketers and MBA’s would try and figure out how to sell the thing, negotiating with retailers, getting their distribution in order, and haggling prices to undercut competitors.

All of that business stuff, the money matters, isn’t particularly something that many of us game developers are really interested in. So it’s understandable that many of us are a bit shocked when are suddenly asked to incorporate the business model into the actual design of the game. In Facebook games, this happens all the time. But my point is that it’s not unique to Facebook. It was true in the 80′s as well.

This main similarity, game design model and business model in one, drives a lot of the other similarities as well.

Instant Gratification and Addiction

In Facebook games, the well developed ones anyway, players Level Up to Level 2 usually in under three minutes. They are receiving XP and Coins even before that. They load the game, and BAM, magical stuff is popping out of everywhere. Chopping trees yields stars and hearts in Frontierville. Clicking cities gives higher Population score in City of Wonder. And before you know it, you’re hit with a massive “Congratulations! Level 2!” screen.

Arcade Coin-Op games were almost identical design-wise. Once the player dropped that 25¢, then the fun flew off at 60 mph. They would quickly get familiar with the controls, and within seconds start racking up points. Grabbing a cherry or chomping down on a pellet would immediately award the player with 10 points, 100 points, 1,000 points. Within a minute they were in the tens of thousands and gaining more every second. The beeps and bloops keep going, and they player feels absolutely great about what they’ve accomplished.

The design intent in all of these games is the same: get the player to feel that they are accomplishing something as soon as possible so that they are hooked on the experience. Whether it’s clicking “Do Job” in Mafia Wars or jumping over barrel #1 in Donkey Kong, the player feels good and knows they are on their way to a high score.

Friendly Competition

What’s more fun than playing a game? Playing a game with friends, of course! Friendship, rivals, and real world competition makes games exciting and fun. Tournaments, guilds, and Thursday night poker games bring people together to enjoy something they all share in common. Thus, it makes sense that friends and other people would work their way into games as a mechanism for deeper player engagement.

We’re all familiar with the viral features of Facebook games, whether we like it or not. “Share Coins and XP with your friends!” “A lost ox has wandered onto your Farm. Will you help it find a home?” “In order to build the shop, you need to get 5 bolts from your friends.” Non-players hate them, which is why Facebook revamped their distribution policy to only have game feeds show up for people who are also playing the game. But players love them; they are re-engaged, and they love hearing about what their friends are doing in a game they also love. Who wouldn’t want to jump back into a game after hearing “James just robbed your Factory! Get him back now!”

In Coin-Op games there was a similar, though less technologically advanced feature: High Score Leaderboards. After each game, on almost every title, players had the opportunity to enter their initials and be displayed as the High Score. They could then see how they stacked up against other players from that arcade. JDC? Ah, I hate that guy! He has 1,444,000 points! I can never seem to top his score!

Again, each of these features were designed to keep people coming back to the game. Like Facebook, they provided a sense of community, which was a powerful way to build fun around the game, not just inside a single play session. And their intent was twofold: to keep people spending more quarters, and also to help people enjoy the game more and provide a sense of challenge.

So Why the Backlash?

Facebook games are similar to our beloved Coin-Op Arcade games in many ways. My point here is that many of the so-called “evils” of Facebook games are not unique to this generation. They have a long history, a history driven by business, a history driven by creating fun player experiences, and a history that has created many wonderful childhood memories for millions.

So why the backlash? Why are we all picking on Facebook games? The outcry reminds me of another outcry that has happened in the game industry in the last few years:

The Wii. When the Wii came out, you could log on to any gaming forming and almost feel the gamer community convulsing with disgust. Wii Sports? Give me a break. These games that my mom and grandma like? They aren’t real games. They’re just garbage.

Sounds familiar, doesn’t it?

Susan Douglas, critically acclaimed feminist author of Where the Girls Are discusses similar phenomena in the mass media. Outcries like this, like the outcry towards Facebook games, towards the Wii, often happen when successful products are made for people other than the usual crowd. When games are made for women instead of men.

When games are made for older non-gamers instead of young players. When things are made that some people just…don’t get. And when the status-quo people don’t understand it, and it’s sucking away millions of dollars, they get upset.

And so while there are many similarities between Coin-Op games and Facebook games as we’ve pointed out, the biggest difference is the demographic. Many Facebook games just aren’t made for core gamers. Halo was made for them. Sorority Life wasn’t made for them. And so while in looking for reasons to explain why these games are worse, we come up with things like “they’re just driven by money”, or “they’re built to get players addicted,” ignoring the fact that many of the games that we grew up on had the same attributes except one: they were our kind of game.

Games For Everyone, But Not Every Game For You

We are rapidly entering into a world where everyone plays games. And I do mean everyone. And that’s going to mean that just as there aren’t TV shows that every single person likes, there are going to be games that are for some people and not for others. And while those differences may be frustrating, may make us ask questions and criticize and pick apart, the end result is going to be that for some games, we just don’t like them.

But if it gets the world to play games, games that they enjoy but I may not understand, then that’s fine by me. (Source: The Game Prodigy)

.jpg)

闽公网安备35020302001549号

闽公网安备35020302001549号