分享设计RPG主要迷你游戏类型的建议

作者:Robert DellaFave

迷你游戏的最大优点在于,为玩家提供了在不同游戏场景中测试自己技能的机会;而它的最糟糕之处就是,它们要么不够完整,要么在游戏情境中无甚意义。在你准备为自己的下一款RPG添加迷你游戏之前,最好先考虑下它们的用途,沉浸因素以及开发时间。对了,不要忘了,还要确保它们的趣味性。

什么是迷你游戏?

在深入讨论之前,我们有必要先定义一下何为迷你游戏。不幸的是,它实际上并没有听起来这么简单。迷你游戏在范围、相关性,以及与游戏核心机制的差异这些方面各有不同。

混合越多,迷你游戏与实际玩法之间的界线就会越模糊。例如,我问两名《魔兽世界》玩家(其中一名只参加公会活动,另一名只玩PvP战斗)PvP场景算是一种迷你游戏还是一个整体玩法功能,我可能就会得到两种截然不同的回答。

鉴于这种情况,我们最好将迷你游戏进行归类,直接将其称为:

游戏中的游戏

主角也有自己的兴趣爱好。迷你的游戏的存在意义就是让我们的英雄有事可做。例如《Chrono Trigger》中的狂欢节游戏,以及《最终幻想X》中同时令人推崇和讨厌的Blitzball游戏。

这类迷你游戏有一些共同点:

*它们在整体上极少具有故事隐喻。

*精通迷你游戏与你能否打败游戏的能力无关。

*玩家通常只需要玩一次这种类型的迷你游戏。

*如果取胜或表现良好,玩家可以获得库存道具、黄金或其他增值升级内容等奖励。

*它们的设计是一种趣味消遣。

此类迷你游戏在90年代晚期和21世纪初极受欢迎,但之后的人气则远不如当初。但也有大量非RPG游戏含有迷你游戏,例如《Mario Party》。

考验你的耐力

你已经打败了成百上千只小猪和森林小妖,穿越了死亡火山并创造了自己的首个传奇。那些强手也注意到了你的战绩,并邀请你参与一场竞技战斗。有些迷你游戏会考验你至今所学到的技能。无论是在战斗还是RPG游戏,尤其是更为现代的游戏中,这些迷你游戏通常会为玩家提供以不同方式利用他们新学技能的选择。其共性包括:

*他们通常对游戏进程没有多大影响。但是,在某些情况他它们可能会要求推进故事发展。

*获胜同游戏进程一样需要一定的精通度。

*获胜奖励通常是物质性或地位性的,而失败可能会导致丧失地位,受伤或者死亡。

这方面的例子包括《暗黑破坏神III》中的Jar of Souls以及《魔兽世界》中的PvP竞技场。而非战斗型的迷你游戏例子可能就是那些测试你对游戏世界知识的掌握情况的问答题了。

胜利或原地踏步

也有一些迷你游戏要求玩家成功完成任务。但如果失败了,通常不会有任何后果。还记得《最终幻想I》中的Phantom Train吗?为了取得进展,玩家必须以合适的模式翻筋斗。另一个例子包括解谜和解决逻辑或空间谜题。普遍特点包括:

*通常来说,失败的唯一惩罚就是停止进前。但是,也有一些例外情况。例如,你可能要先解开一个谜题才可能得知地下宝藏的入口。在这种情况下,你仍然可以在未“打败”迷你游戏的前提下获得进展,虽然你可能会错过那把新宝刀。

*与之相似,获胜的奖励通常就是推动游戏进程。

*这类迷你游戏更依赖不断试错、创意思维以及其他非战斗能力等二级技能。

*“获胜或原地踏步”型的迷你游戏通常会整合到游戏的主要情节中。

我知道这令人难以置信,但有些游戏开发者就具有虐待狂倾向。他们不仅仅会因为你翻错一个跟斗而阻挡你的去路,还会将你彻底杀死!我建议只有在迷你游戏本身并不那么复杂,以及玩家能够找到与答案相关的进示这种情况下才可以采取这种路线。

获胜或者自食其果

“获胜或者自食其果”型迷你游戏与“获胜或原地踏步”型迷你游戏极为相似,唯一区别就在于复杂性有所增加,并且失败会导致游戏结束分叉。通常情况下,“获胜或自食其果”型迷你游戏会耗尽游戏的延长环节。这正是迷你游戏以及核心玩法功能之间的界线开始变模糊的地方。但为了方便我们叙述,我们将把这些结果视为“并不太迷你”的迷你游戏。我们的逻辑就是,因为这些结果偏离了RPG中的刷任务和探索惯例,它们在一定程度上算另一款不同的游戏。西方现代RPG整合了这种类型的许多结果。在此我们就不讨论延展性的玩法偏离应该算游戏的核心属性还是迷你游戏这个话题了。但是,无论是哪种情况,将它们整合进去需要一个严密而深思熟虑的设计方案。这就引出了我们的下一个话题:

迷你游戏设计建议

好消息在于上述提到的迷你游戏类型可以给RPG增加额外的深度。但在你投入创造一个不规则竞技场或司法机构之前,重要的是先考虑迷你游戏对你的开发循环会产生什么影响。铭记这一点,让我们记住迷你游戏的以下常见规则:

迷你游戏也是游戏!

首先,迷你游戏就是游戏。你可能会很意外地发现有许多开发者将迷你游戏视为插科打诨的新奇事物而已。好吧,那么这一点为何这么重要呢?回顾一下《最终幻想X-2》中的迷你游戏桥段你就知道了。但更具体地说,那些无法获得足够关注的迷你游戏不可避免地会使整个游戏体验逊色。这是个坏消息。

为了解决这一问题,就要将每个迷你游戏视为独立的游戏,遵从与主要游戏相同的前期制作、制作和后期制作标准。重要的是,要让你的游戏至少在该游戏情境下合情合理。

成本考虑

作为一名独立开发者,你可能预算非常有限。而不管是16位的RPG,还是开放世界沙盒RPG,都是一个庞大的项目。光是平衡游戏这一过程就足以至少让团队耗尽数月时间。也就是说,你在为RPG引进任何新功能之前都必须谨慎考虑其中的风险投资回报率:尤其是支线任务和迷你游戏。这需要开发者做出一些困难的管理决策。

为了让你的任务更轻松,一开始就要自问:“我真能负担得起设计、分配资源、编码和优化迷你游戏理念这些工作吗?”如果答案是否定或者不确定,那就要重新评估迷你游戏的范围,将其替代成你的团队能够处理的迷你游戏,或者将其彻底抛弃。

如果你发现自己超出了预算,或者被迫削减预算,那可能就要最先在迷你游戏上动手。这正是我建议你在游戏开发末期执行迷你游戏的一个原因。这并不是说你不需要事件做好计划 ,而是指应该以你的游戏核心功能为主导。

游戏中的游戏:添加迷你游戏很棘手

迷你游戏无需极具意义,或者与游戏世界紧密融为一体,但它们至少要有在游戏情境中存在的理由。我想起一款付费获胜、发生于奇幻背景的MMORPG,它颇具哈里波特电影风格。玩家可以获得许多召唤咒语和直接施咒,在每个关卡中都会变得更加强大。这相当合理。

但游戏中有个怪异的特点。为了快速存储你的魔法能量,你得走向游乐场,并玩一个不成熟版本的Tetris Attacks、Dig Dug或Concentration游戏。这一体验很费劲和脱节。更糟糕的是,在游戏早期这是唯一补充你宝贵资源的可行方法了。通过赢得大量点数,你可以获得其他奖励,但其中投入的时间与回报却并不成正比。

这种MMORPG几乎打破了每一条如何制作“游戏中的游戏”规则。你可千万别效仿。

在设计一款迷你游戏之前,要将你的游戏世界和主角牢记在心。例如,你的英雄是一个左臂佩戴一刀的壮硕水兵,那么他真的会对玩沙滩排球感兴趣吗?《辐射3》中的居民会在缺电的情况下玩电子游戏打发时间吗?巫师会通过玩Dig Dug来补充自己的能量吗?显然不会。

但是,地下赌场在遭遇大劫难的世界背景中却颇为合情合理,就好像全息纸牌游戏在科幻游戏中一样自然。关键在于,迷你游戏并不一定要利用与游戏本身相同的机制,只要它们在该情境中合理即可。其他设计这种“游戏中的游戏”通用原则还包括:

*要求:永远不要强迫玩家掌握这种类型的迷你游戏。最多迫使他们尝试一次。如果他们喜欢,那很好。让他们根据自己的意愿玩游戏。

*奖励:通过提供奖励,给予玩家掌握迷你游戏的理由。将奖励内容局限于增量升级和可通过其他途径赢取的道具。如果奖励过于强大,或者别处无法获得,那些不喜欢迷你游戏的玩家就会处于劣势了。在最糟糕的情况下,这会让你整款游戏都失去平衡。

*原创:以其他迷你游戏作为灵感来源,但不要剽窃它们。如果游戏玩家想玩《俄罗斯方块》,他们可以玩原版或其他变体版。否则,就要给予玩家体验你的迷你游戏的充分理由。

*润色:如果你的迷你游戏崩溃了,漏洞不断,或者比起游戏其他部分缺少了什么,玩家就会注意到了。正如之前所言:如果你无法做好,那最好都不要去做。

注意这类更有野心的迷你游戏会让你的开发周期增加更多时间和成本,所以如果你预算有限就要回避这种情况了。

可以添加要求玩家去体验“游戏中的游戏”这种提示

只有以下这些情况,我才鼓励开发者迫使玩家去体验“游戏中的游戏”:

*迷你游戏兼作一项技能。例如,撬开门锁会增加你在游戏中撬开更多困难门锁的能力,撬锁的艺术和迷你游戏一样算是一种技能。《天际》中植入的撬锁功能就是这方面的典型例子。

*用户有多种完成任务的方式。例如,让玩家去对付一扇紧锁的门。他应该可以选择撬锁,也可以使用爆破技术炸开这扇门,或者使用强力把门砸开,总之他可以根据自己偏爱的玩法风格和独特技能来完成任务。因此,不要让玩家去玩某一款迷你游戏,而要让他们去玩多款迷你游戏之一。

*除非成功完成迷你游戏,否则玩家无法取得进展。

考验你的耐力

这类迷你游戏会考验你究竟有多棒。这种迷你游戏的主要优势就在于,你不需要引进任何新玩法机制,因为它们依靠的是一种现成的玩法。但是,由于它们通常以不同的形式出现,所以可能会有额外的美术和音乐资产,以及游戏逻辑调整等要求。但是,这也总好过一切重新创造。

“考验你的耐力”型迷你游戏的另一个好处就在于,它们可能是基本或非基本的,拥有严厉的惩罚或者根本就没有惩罚,总之一切选择在你。但是,我认为任何惩罚都要与情境对应。如果你成了整个银河系中的顶级竞技斗士,并遇到了之前终极斗士冠军的挑战,你就可能会战死。虽然这很残忍,但至少是合情合理的。

并非所有“考验你的耐力”型迷你游戏都必须是战斗型的。你可以植入一个在特定时间段从世界的一端穿越到另一端的故事序列,利用你对游戏世界的了解来帮助自己成功完成任务。或者你也可以利用自己的说服技巧令自己摆脱困境。无论是什么任务,都要尽量遵守以下规则:

*等比例的难度:竞技场战斗应该更为困难,如果失败的话最终会导致可怕的结果——甚至是死亡。

*奖励:如果没有奖励,那就没有参与挑战的理由了。有时候奖励可以是让玩家幸存下来,但如果迷你游戏是可选择型的,玩家就必须得到一些获胜的动机。

*合而不同:强迫玩家采用不同的战术。WoW中的PvP比纯粹的DPS更依赖躲避和防御。通过挑战玩家来尝试新建筑和技术,你的游戏可以获得巨大的价值,但却不会让开发团队付出多少成本。

获胜或原地踏步:如果迷你游戏失去趣味,就会变成枯燥的任务

“获胜或原地踏步”型迷你游戏有一系列优势。它们相对容易执行,所以颇为划算。它们还可以打破传统上与多数RPG相关的战斗/探索循环。所以,它们可能有一点投机取巧,但没有关系,只要它们设计精良,并且挑战玩家的二级技能即可。这还有助于避免它们过于无趣。

如果你是《最终幻想VI》粉丝,你可能就会记得Zozo钟谜题。玩家可以从不同NPC那里获得与这个钟的时间有关的提示——只是这个小城充斥着许多骗子。因此找到正确时间的唯一方法就是排除所有错误的时间。这些NPC没有提到分针所指的时间。为了解开这一谜题,玩家必须检查另一个钟的时间。所幸玩家可以得到足够的提示,从而推断出解开谜题的方法。

要知道令人受挫的“获胜或原地踏步”型迷你游戏与设计精良的此类迷你游戏之间的区别就在于:提示。如果没有提示,更困难的谜题就需要玩家更多次试错才能解谜,而这最终只会演变成一种无聊的任务。这并不是说提示必须一目了然,而是指必须含有提示。如果你预算有限,就要考虑多次采用相同的“获胜或原地踏步”型迷你游戏。如果你选择这么做,就要将这些建议铭记在心:

*学习曲线:迷你游戏也需要一个学习曲线。让迷你游戏的首个操作成为一个完整的教程,并据此逐步提升难度。

*要求或选择性的:多数此类迷你游戏都要求玩家必须成功完成任务才能推动情节发展。但是,没有必要融入数个选择的变体版本。要让可选择的任务成为游戏中最困难的一个,并为玩家提供征服这一挑战的特殊奖励(游戏邦注:例如进入藏宝室等)。

*趣味因素:摁压开关可能很无趣,尤其是在你同多个敌人交战的时候。遇到这种问题要摆脱常规思维。例如,谜语、战斗谜题或计时迷宫可能就会比按顺序点燃火把更有趣。如果你决定采用更为传统的做法,那就要确保取得相当的效果。

获胜或自食其果:极富野心的游戏

毫无疑问,最耗时间和最费成本的迷你游戏的主要益处就在于,它们真的很棒。

以《星球大战:旧共和国武士》中的谋杀调查现场为例,在高达两个小时的游戏时间中,玩家要抛开他们的光剑,去做一些老式的侦探工作。这要求玩家采用截然不同的技能,迫使他们禁得起劝说,这个故事序列成了不同于与敌人战斗、探索新大陆和掌握新技能的新颖任务。我认为《星球大战:旧共和国武士》整款游戏都因此而受益。

更棒的是,你的行动还会产生持久的结果。你会得到一个反对相关证据的选择。这样你可以得到一些Dark Side积分奖励。

这种“获胜或自食其果”型迷你游戏不适合不敢冒险或预算有限的开发者,它需要精妙的创新、趣味和情境。其中的支线任务是选择性的,通常还包括核心游戏机制,“获胜或自食其果”迷你游戏完全不同于你至今所经历的内容。所以要小心设计这类游戏,并对其进行充分测试。

最重要的是,要衡量其中的风险。不要为了植入一个让玩家痛恨的情节设置而让自己的预算和开发时间增加了20%。

总结

让我们看看不同迷你游戏类型的成本与价值比:

*游戏中的游戏:高预算和制作时间,对玩家的价值有所不同。作为一种技能,游戏中的游戏价值会增长。

*考验你的耐力:低预算和制作时间,价值中等。

*获胜或原地踏步:你低成本和制作时间,低至中等价值。

*获胜或自食其果:中至高成本和制作时间,高价值。

通过为你的大型迷你游戏提供情境,以及有意岔开的分支提供趣味,你可以为自己的RPG增加深度、重玩价值和额外层次。只是要在进入制作阶段之前清楚自己的方向,并时刻牢记时间和预算限制。(本文为游戏邦/gamerboom.com编译,拒绝任何不保留版权的转载,如需转载请联系:游戏邦)

Designing RPG Mini-Games (and Getting Them Right)

by Robert DellaFave

The following blog post, unless otherwise noted, was written by a member of Gamasutra’s community.

The thoughts and opinions expressed are those of the writer and not Gamasutra or its parent company.

At their best, mini-games offer players a meaningful way to test their skills in an alternative game setting. At worst, they’re either incomplete or make little sense within the game’s context. Before peppering your next RPG with mini-games, it is imperative that you consider their purpose, immersion factor and development time. Oh, and don’t forget: they should also be fun.

This post originally appeared on Tuts+, where you can find more of my RPG design tutorials.

What Is a Mini-Game?

What better way to start off a piece on mini-games than by defining exactly what a mini-game is? Unfortunately, that’s not as simple as it might initially sound. Mini-games vary widely in scope, in relevance, and in how much they deviate from a game’s core mechanics.

Compounding matters further, the line between a mini-game and an essential feature can sometimes be blurred. For instance, if I asked two World of Warcraft players, one who only raids and one who PvPs (that is, takes part in player vs player combat) exclusively, whether the PvP arena is a mini-game or an integral feature, I’d probably receive two completely different answers.

With that in mind, it may be best to group mini-game types—or perceived types—into categories first. Without further ado:

A Game Within a Game

Protagonists have hobbies too. Mini-games of this nature, for lack of a better term, give our hero something to do. The carnival games in Chrono Trigger and the simultaneously revered and loathed Blitzball from Final Fantasy X come to mind.

These types of mini-games have several things in common:

They have minimal implications on the story as a whole.

Mastering the mini-game will have little to no bearing on your ability to beat the game.

Players are typically only required to play this type of mini-game once, if at all.

By winning or playing well, players are rewarded with inventory items, gold or other incremental upgrades.

They’re designed to be a fun diversion.

Mini-games of this nature were exceedingly popular in the late 1990s and early 2000s, but have since fallen slightly out of favor. That said, there have been a slew of non-RPG releases that consist solely of mini-games—think Mario Party.

Test Your Mettle

You’ve defeated hundreds of fledgling pigs and forest imps, traversed the Volcano of Doom and crafted your first legendary quiver. Your feats have gone noticed by the powers-that-be and they have invited you to participate in arena combat. Some mini-games will test the skills you’ve learned thus far. Whether it be in battle or otherwise, RPGs, particularly more modern ones, will often provide players with the option to utilize their newly honed skills in alternative formats. Commonalities include:

They generally have little impact on progression. However, in some cases they may be required to advance the story.

Winning requires the same proficiency as game progression does.

The rewards for winning are usually material or status-worthy in nature, while losing can result in loss of status, injury, or death.

Examples include the Jar of Souls event in Diablo III, and World of Warcraft’s PvP arena. A solid non-combat example would be a quiz that relies on your knowledge of the game world.

Jar of Souls: Not as foreboding as it initially looks.

Win or Stay Put

And then there are mini-games that require successful completion. Failure to do so usually results in, well… absolutely nothing at all. Remember the Phantom Train from FFVI? In order to progress, players must flip the appropriate switches. Other examples include deciphering riddles and solving logic or spatial puzzles. Common characteristics include:

Generally speaking, the only penalty for failure is stunted progression. However, there are exceptions. For instance, you may be tasked with solving a puzzle before gaining entry to an underground treasure cove. In this case, you can still progress without “beating” the mini-game, although you’d be missing out on that new broadsword.

Likewise, the reward for winning is usually continued progression.

Mini-games of this nature rely more on trial-and-error, creative thinking, and other secondary skills than they do fighting ability.

“Win or stay put” mini-games are typically integrated into the main plot.

I know its hard to believe (not really), but some game developers are sadistic. Instead of merely denying you passage for flipping the wrong switch, they’ll kill you off! I’d only advocate going this route if the mini-game itself isn’t exceedingly complicated and the player is either provided with or can find clues regarding its answer.

Win or Suffer the Consequences

“Win or suffer the consequences” mini-games are very similar to “win or stay put” mini-games, with the only exceptions being increased complexity and that failure can result in game-ending ramifications. Often, mini-games of the “win or suffer the consequences” variety eat up elongated sections of the game. It is here where the proverbial line in the sand between what is a mini-game and what is an essential gameplay feature begins to blur. But for our purposes, we’ll dive right in, and treat these sequences as “not-so-mini” mini-games. Our logic being that because these sequences deviate from the RPG staples of grinding and exploration, they are in some ways a different game. Modern Western RPGs incorporate multiple sequences of this type. I’ll leave the discussion of whether or not extended gameplay deviations are core attributes or mini-games up to you. But, either way, incorporating them requires a disciplined, well-thought out design schema. Which segues nicely into our next topic:

Mini-Game Design Tips

The good news is that each aforementioned type of mini-game can add extra layers of depth to an otherwise by-the-numbers RPG. But before you commit yourself to building a sprawling arena or judiciary establishment, it’s imperative to first consider the impact mini-games will have on your development cycle. With that in mind, let’s kick things off with a few general guidelines before diving into mini-game type specific tips:

Mini-Games Are Games Too!

First and foremost, mini-games are just that: games. Painfully obvious, I know, but you’d be surprised at how many developers view them as mere novelties. Alright, so why is this important? Recall the massage mini-game from Final Fantasy X-2—that’s why. But, more specifically, mini-games that aren’t given the attention they deserve inevitably detract from the overall gaming experience. And that’s just bad news.

To counter this, treat each mini-game as an individual game, subjecting to the same pre-production, production and post-production standards that you would your main game. Going further, it’s vital that your game at least makes sense within the game’s context; more on that later.

Cost Considerations

As an independent developer, you’re probably on a rather modest budget. RPGs, regardless of whether they’re a 16-bit homage or an open world sandbox, are massive undertakings. Just the balancing process alone has set teams back months, if not years. That said, you must carefully consider the risk-reward ratio of introducing any new feature into your RPG: side-quests and mini-games especially. This will require making some difficult managerial decisions.

To make your task easier, start off by asking yourself: “Can I really afford to design, allocate resources to, code, and polish my idea for a mini-game?” If the answer is “no” or “maybe,” either reevaluate the mini-game’s scope, replace it with a mini-game that your team can handle, or ditch it entirely.

And if, at any point, you find yourself over-budget or late and forced to make cuts, mini-games should be one of the first features to go. It’s for this reason that I suggest waiting until near the end of your development cycle to implement them. That’s not to say they shouldn’t be planned for in advance, but your core functionality should always take precedence.

A Game Within a Game: Tacked on Mini-Games Are Tacky

Mini-games don’t have to be meaningful or intimately tied to the gaming world, but they should at least make sense in the game’s context. I recall reviewing a pay-to-win MMORPG that took place in a high-fantasy setting, reminiscent of the Harry Potter movies. Players gained access to a myriad of summoning spells and direct casts, growing more powerful with every level. Standard fare, really.

But there was one peculiarity. In order to quickly restore your magical energy, you would head down to the Fairgrounds and play an unpolished, feature-light version of either Tetris Attacks, Dig Dug or Concentration. The experience was laborious and disjointing. Even worse, early in the game it was really the only viable way to replenish your valuable resources. By scoring an inordinate amount of points you could win other prizes, but the time investment was hardly worth the reward.

This MMORPG broke nearly every rule on how to make “a game within a game.” But you won’t do the same.

Always keep your game world and protagonist in mind before designing a single mini-games. For instance, if your Hero is a burly ex-Marine with a sword for his left arm, would he really be interested in playing beach volleyball? Would the residents of a game like Fallout 3 pass the time playing video games, despite the lack of electricity? Would a Wizard replenish his magical energy playing Dig Dug? Clearly not.

Yes, because this makes sense in a game about wizardry.

However, an underground casino would make total sense in a post-apocalyptic setting, as would a holographic card game in a science fiction game. The point is, mini-games don’t have to necessarily utilize the same mechanics as the game itself, as long as they make sense within its context. Other general rules to follow when designing a “game within a game” include:

Requirements: Players should never be forced to master a mini-game of this variety. At most, force them to try it out exactly once. If they enjoy it, great; let them play it to their hearts’ content.

Rewards: Give players a reason to master a mini-game by gifting them with rewards. Limit the rewards chart to incremental upgrades and items that can be won via other means. If the rewards prove too powerful or are otherwise inaccessible, players who don’t enjoy mini-games will be placed at a severe disadvantage. In a worst case scenario, this will unbalance your entire game.

Originality: Use other mini-games for inspiration, but don’t rip them off. If gamers wanted to play Tetris, they can play the original version or one of its many variants. Instead, give players a specific reason to play your mini-games.

Polish: If your mini-game is broken, buggy, or otherwise lacking compared to the rest of your game, players will notice. As I mentioned before: If you can’t do it right, it’s better not to do it at all.

Do note that more ambitious mini-games of this assortment will add serious time and costs to your development cycle, and should be avoided if you’re on a strict budget.

A Note on When Requiring Players to Play “A Game Within a Game” Is Acceptable

There’s only one set of circumstances where I would advocate players being forced to play a “game within a game”:

The mini-game doubles as a skill. For instance, if picking locks increases your in-game ability to pick more difficult locks, the art of lock picking is just as much a skill than it is a mini-game. Skyrim’s implementation of lock picking is an excellent example of this.

The user is given more than one means of completing the task. For example, a player approaches a locked door. He should be given the option to either pick the lock, use his knowledge of explosives to blow up the door, or use sheer brute force to knock it down, depending on his preferred playing style and unique skill set. Thus, instead of requiring players to play a mini-game, you’re only asking them to play one of many mini-games.

Players cannot proceed unless the mini-game is successfully complete.

Modern lock picking at its finest.

Test Your Mettle: To Arms!

Ah, the mini-game that tests just how good you really are. The main advantage of this type of mini-game is that you won’t have to introduce any new gameplay mechanics, as they already rely on existing ones. However, because they generally take place in alternative formats, they may require additional art and music assets and game logic tweaks. Still, that’s better than reinventing the wheel.

The other beauty of “test your mettle” mini-games is that they can be essential or nonessential, have severe penalties or none at all; the choice is really up to you. However, I would suggest that any imposed penalty match the context. Case in point: if you’ve become the top arena fighter in the entire galaxy and are challenged by the former undisputed champion, you should probably fight to the death. Barbaric I know, but it makes sense.

Not all “test your mettle” mini-games need to be combat-based. You may implement a sequence where you must travel from one end of the world to another in an allotted amount of time, using your prior knowledge of the world to help you succeed. Or you may be tasked with relying on your skills of persuasion to talk yourself out of a sticky situation. Whatever the task, try to adhere to the following:

Difficulty scaling: Arena battles should become more difficult, and losing should eventually bear dire consequences—even death.

Rewards: Without rewards, there is little reason to participate in a challenge. Sometimes the reward will be that you survive, but if the mini-game is optional, players must be given some sort of incentive for winning.

Same but different: Force players to employ slightly different tactics than they would otherwise. PvP in WoW relies on evasion and defense more than it does on pure DPS. By challenging players to experiment with new builds and techniques, your game gains enormous value, all at little cost to the development team.

Win or Stay Put: When Mini-Games Stop Being Fun, and Start Becoming Chores

“Win or stay put” mini-games offer a slew of advantages. They’re relatively simple to implement, and thus cost effective. They also do a nice job of breaking up the combat/exploration cycle typically associated with most RPGs. Alright, so they might be a little gimmicky, but that’s OK, as long as they’re well-designed and challenge players to use a secondary skill set. It also helps if they’re not painfully boring.

If you were a fan of Final Fantasy VI, you may recall the Zozo clock puzzle. Simultaneously exhilarating and brilliant, players would receive clues from various NPCs regarding the time on a clock—only, the town was comprised of a bunch of liars. Thus the only way to figure out the right time was by eliminating all the wrong times. Compounding matters, the NPCs made no reference to the minute hand. In order to solve that piece of the puzzle, players were tasked with examining another clock. Thankfully, you’re given just enough clues to deduce how to solve the puzzle.

What time is it again?

And that’s the difference between a frustrating “win or stay put” mini-game and a well-designed one: clues. Without them, more difficult puzzles will require an extraordinary amount of trial and error, ultimately becoming a bore. Now, that’s not to say the clues need to be blatantly obvious, but they should exist. If you’re on a budget, consider relying on the same “win or stay put” mini-game more than once. If you choose to do so, keep these other handy tips in mind:

Learning curve: Mini-games need a learning curve too. Let the first instance of a mini-game act as a sort of integrated tutorial, and ramp up the difficulty accordingly.

Required or optional: Most mini-games of this variety must be successfully completed in order to progress the plot. However, there’s no reason not to weave in a couple of optional variants. Make the optional ones the hardest in the game, and reward players who conquer them with access to a treasure room or other special treat.

Fun factor: Pressing switches can be a chore, especially if you’re fighting enemies in between. Counter this by thinking outside of the box. For example, a riddle, combat puzzle or timed maze might prove more interesting to players than lighting torches in a particular order. And if you do decide to go a more traditional route, make sure the payoff is worthwhile.

Win or Suffer the Consequences: Awesomely Ambitious

Undoubtedly the most time consuming and costly mini-games to implement, the major benefit of “win or suffer the consequences” mini-games are that they are truly awesome.

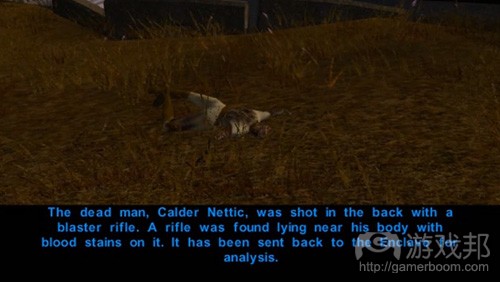

Take the murder mystery investigation scene from Star Wars: Knight of the Old Republic, for example. For upwards of two hours of game time, players are asked to put away their lightsaber and do some old-school detective work. Requiring an entirely different set of skills, force persuasion withstanding, this sequence acts as a refreshing change from the norm of fighting enemies, exploring new lands, and acquiring skills. I’d argue that the game as a whole benefits from it.

The infamous KOTOR murder mystery investigation. Whodunit?

Better yet, there are long-standing consequences to your actions. Without giving too much away, you’ll be given the option to go against the evidence. Doing so results in a whole slew of Dark Side points.

Not for the faint of heart (and light of wallet), “win or suffer the consequences” mini-games require a delicate juxtaposition of novelty, fun and context. Whereas side quests are optional and typically incorporate core game mechanics, “win or suffer the consequences” sequences are complete deviations from everything you’ve experienced thus far. Design them with care, and playtest the heck out of them.

Most importantly, gauge the risk involved. The last thing you want is to increase your budget and development time by 20% just to incorporate an alternative plot device that players abhor.

On a personal note, one of the games I’m working on—Hiro Fodder: A Blue Hope—incorporates one of these sequences. Our little blue slime undertakes a heroic journey to infiltrate the human city. Doing so requires him to find expose secret passageways, uncover clues and spy on guards without appearing in their field of vision. It’s terrific fun, but, admittedly a gigantic risk.

Conclusion

Let’s look at an overview of the cost-to-value ratios of the different mini-game types:

Game within a game: High expense and production time; value to gamer varies.

As a skill, a game within a game’s value increases.

Test your mettle: Low expense and production time; moderate value.

Win or stay put: Lower cost and production time; low to moderate value.

Win or suffer the consequences: Mid to very high cost and production times; high value.

Be providing context to your larger mini-games, and fun to your purposely divergent ones, you can add depth, replay value and additional layers to your RPG. Just be aware of what you’re getting into before entering production, and always keep your time and budgetary restraints in mind.(source:gamasutra)

上一篇:阐述有效的用户体验设计的注意要点

闽公网安备35020302001549号

闽公网安备35020302001549号