为什么我们应该将游戏比作戏剧?

作者:Nate Ewert-Krocker

我经常在许多对于游戏前提的描写中看到一个短语,即在某某游戏中,“玩家扮演的是**角色”。通过在谷歌搜索这个字段,我们便能获得一些与电子游戏相关的答案,但直到最近我才真正开始正视这一术语。

除了游戏,唯一能够使用类似表达的媒体便是戏剧,但是我却未在任何游戏资讯中看到将玩家与演员相提并论的内容。但是我个人却认为拾起控制器与拿起脚本在很多方面看来其实非常相似。

大多数参与过戏剧表演的人都应该非常熟悉所谓的“演员的噩梦”:在表演过程中你忘了自己的台词,而演对手戏的人则不断地催促你,尽管事实上你根本没有脚本,也没有戏装。

而我认为玩电子游戏,或者至少是玩那些带有故事情节的游戏都与“演员的噩梦”非常相似——你在扮演游戏故事中的某个角色,虽然不清楚任何台词但却仍需要踏上一个大舞台,而非常神奇的是每当你进入下一个故事时,所有台词都会不知觉地从你嘴巴蹦出来。

当我们说玩家“扮演”的是John Marston,Commander Shepard甚至是Sly Cooper时,这便意味着我们不只将这些角色作为完成游戏目标的代理,同时他们也在积极扮演一个角色而赋予游戏生命。

我想《刺客信条》应该是在这种角色扮演中做得最到位的一款游戏。你的生命值指示器能够有效地衡量你的角色在游戏过程中的健康状况。因为在游戏中玩家如果扮演的是Desmond Miles,他将能够呈现出玩家的人格,而如果玩家与历史上的刺客难以保持“同步”,他便会遭遇失败。

杀死平民?Altair(游戏邦注:《刺客信条》的主角)绝对不会这么做的!千万不要再这么做了,否则你将再次出现“不同步”,并因此遭遇失败。如果你在执行任务时被发现了或者在游戏世界中进退两难的时候,这便是你结束游戏的一个很好的理由。

尽管《刺客信条》是少数一些围绕这一原理构建游戏世界的游戏,但却不意味着其它游戏不适合这一原理。有多少人觉得在《黑色洛城》中控制Cole Phelps非常不协调?Cole简直就是一个混蛋!

在舞台上扮演一个混蛋并不容易。但是Cole Phelps并不是玩家,他只是游戏所使用的代理而非游戏角色,也就是说他并不会直接传达玩家的人格。我们并不是混蛋,我们只是在游戏中控制一个混蛋而已。

然而这与其它媒体并不相同:即玩家只能够控制Cole在谈话中的行为而已(当然,这不像他们在控制Commander Shepard的谈话那样自由,即使是这种情况也存在许多不协调元素!)。有时候我会带着满满的质问惊慌后退。“啊,侦探!他们告诉我X按钮意味着‘怀疑’,而不是‘替换证人!’”

然而我却非常热衷于玩《黑色洛城》中的角色。除非身处追逐场景中,我都会非常小心地驾驶着我的车辆,即使能够猛冲我也只会选择慢慢前进,我甚至不会在满是人流的大街上横冲直撞。许多玩家希望推翻游戏世界的界限并检测游戏究竟提供了多大的空间;但是也有许多玩家并不希望打破这种界限,因为这也将打破他们的幻想。

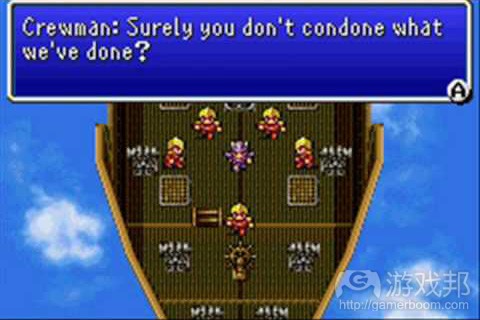

我曾经阅读过许多关于过场动画所存在的问题及其在游戏中的安置等讨论,但是我认为Alois Wittwer所提出的噩梦模式是站在为这一问题辩护的立场上。Wittwer以《最终幻想IV》的开场为例子进行说明,阐述一个我们不能控制的场景是如何将我们带进游戏世界中:我们将在游戏中扮演Cecil Harvey,而他在游戏中做了一些应受谴责,并且我们也难辞其咎的事情,所以我们有必要与他一起赎罪。

Cecil是一个军事组织中的成员,他们为了获得一些珍宝(《最终幻想》中一种普遍的水晶)而洗劫了一个无辜的村庄。在此玩家没有多少代理:在玩家能够真正控制英雄前,却只能眼睁睁地看着几场战斗发生。反对过场动画(支持玩家代理)的人认为我们不应该对Cecil的罪行感到自责,因为我们没有选择。与Cole Phelps一样,Ceci也只是游戏中的代理,并不是真正的游戏角色。他并不是玩家的代表,他只是我们不得不接纳的一个角色而已。

而Cecil所面临的困境是他并不能够控制自己所处的情境,他只是在为一个自己不再信任的国王卖命,执行着一些自己会感到懊悔的行动。而带有同情心的玩家自然希望帮助他逃离这种境况(并在帮助他后感到自我满足)。

任何参与过戏剧演出的人都会说戏剧表演非常有趣。扮演一个特殊的角色并与同伴们共同为观众们演绎一个故事是一种非常让人满足的体验。而游戏中的好故事也能推动着玩家参与并融入其中,而不需要别人的帮助。我们扮演一个角色只是因为我们站在舞台上,并相信游戏设计师所创造的内容。

许多游戏评论已经反复陈述了玩家既是创造者也是观众这一事实,并且没有其它媒体能够体现出这一点——但是我想补充的是,如果要说哪种媒体最接近这种效果,那只能是戏剧。在舞台上,演员们将融入一个实时展开的故事,并且这里不存在任何后期制作。舞台作品创造者与观众间进行交流的唯一台词是无形的,假设性的,且是双方共同认可并受到所有参与人员所重视的。

玩游戏就像是身处移除了第四堵墙(游戏邦注:戏剧术语,指沿台口的一面不存在的墙,它的作用是将演员与观众隔开,使演员忘记观众的存在,而只在想象中承认“第四堵墙”的存在 ) ,观众受邀参与其中,并立刻知晓了所有台词。多么神奇啊!随后有些玩家甚至会因为游戏代理提供生产服务而想要抛弃他们。

比起电影,我们认为游戏更类似于戏剧。而游戏设计师们更应该清楚这一点,特别是当他们在思考玩家代理设计时。如果我们将游戏玩家视为自己所扮演的角色,我们应该会以不同方式进行演绎,并因此而提高了自己的游戏体验!(本文为游戏邦/gamerboom.com编译,拒绝任何不保留版权的转载,如需转载请联系:游戏邦)

Why we should be comparing games to theater

I’ve read very often, in descriptions of a game’s premise, a phrase which I’ve begun to consider: In a given title, “players take the role of”…. A Google search of this phrase naturally turns up almost exclusively hits relating to video games, but it wasn’t until recently that I sat down and really considered the terminology here.

The only other possible medium besides gaming to which this might apply is theater, and yet I don’t see a lot of criticism in games journalism drawing parallels between players and actors. It strikes me that picking up a controller and picking up a script are, in many respects, quite similar.

Most folks who’ve done some theater are familiar with “the actor’s nightmare”: You are in the middle of a performance for which you have forgotten all of your lines and most of your cues, and you are constantly being urged by your castmates to continue despite the fact that you have no script, no costume, and no pants.

I think that playing a video game, or at least any game with a narrative, is a bit like the actor’s nightmare with all of the bite removed — you have assumed a role, you set foot onto a grand stage knowing none of the lines, and yet miraculously, every time you reach the next bit of the story, the words come tumbling from your mouth unbidden.

When we say that the player “takes the role of” John Marston, Commander Shepard, or even Sly Cooper, the implication is that we’re not just using these characters as agents by which to accomplish gameplay objectives, but we are actively taking on a role — as an actor takes a role in bringing a play to life.

I wish I’d had a health bar when I did theater in high school.

The Assassin’s Creed franchise has probably the most direct implementation of this of any game that I can think of. Your health bar effectively measures how in-character you are when you’re playing. Because of the narrative conceit that you are Desmond Miles taking on the personae of his ancestors, the game will cause you to fail if you act “out of sync” with these historical assassins.

Kill a civilian? Nope, Altair didn’t do that! Don’t do it again or you’ll be “desynchronized!” Essentially, you fail if you are out of character. This is an excellent excuse for giving you a game over if you’re detected on certain missions (“Oops! Ezio wouldn’t have gotten caught there!”) as well as constructing the limits of the game world. (“Altair never swam a foot in his life!”)

Just because the Assassin’s Creed games are some of the only ones to take this concept and construct their world around it doesn’t mean the principle isn’t at work in other games. How many of us felt an uncomfortable dissonance playing Cole Phelps in L.A. Noire? Cole’s kind of a jerk!

Look at him! He knows it.

It’s not easy being a jerk onstage. Cole Phelps, however, isn’t the player; he’s an agent rather than an avatar, meaning that he doesn’t directly represent the player’s persona. We’re not jerks; we’re just playing one in the game.

Nevertheless, this sort of thing isn’t as black and white as it can be in other media: The player has some agency over how Cole behaves in conversations but not a lot (certainly not as much as they do in the conversations of Commander Shepard — and yet, even there, there’s some dissonance!). Sometimes, in the midst of an interrogation, I would back off in alarm. “Whoa, Detective! They told me the X button meant ‘doubt,’ not ‘tear the witness a new one!’”

Nevertheless, I played an awful lot of L.A. Noire “in-character.” I was careful with my driving unless we were in the middle of a chase scene, I walked when I could have dashed, and I didn’t run people down in the street. Many players like to push the boundaries of the world and test the limits of the play space they’re given. There are plenty of others who don’t — players who don’t like to break the game because it breaks the illusion.

I’ve read a lot of arguments considering the matter of cut-scenes and their place in gaming, but I think that this one, by Alois Wittwer over at Nightmare Mode, might be among the few I’ve read in defense of them. In discussing player agency, Wittwer uses the excellent example of Final Fantasy IV’s opening to show us how a scene over which we have no control can be used to invest us in a world: We’re taking on the role of Cecil Harvey, who does something pretty reprehensible in which we’re immediately complicit, and so his redemption over the course of the story is in some way shared by the player.

Boy, it’s a shame you didn’t do something about it, huh?

Cecil is a member of a military organization which ransacks a tiny, helpless village to obtain a precious resource (one of the ubiquitous crystals in the Final Fantasy franchise). The player has very little agency here: A long story sequence, including a handful of battles, plays out before we’re given control of our hero. The argument against cut-scenes — the argument for greater player agency — suggests that we can’t feel guilt over Cecil’s actions because we had no choice in them. Like Cole Phelps, Cecil is an agent, not an avatar. He’s not representative of the player; he’s just a role we’re taking on.

Cecil’s plight, however, is that he’s not in control of his situation any more than the player is; he’s in service to a king he no longer trusts, committing acts for which he feels remorse. A sympathetic player naturally wants to enable his escape from such a situation (and will feel satisfaction for him when we finally help him to do so).

Anyone who has played a part in a theater production at any level will tell you that there is great joy in putting on a play. Taking on the role of a character and working with comrades to bring a story to life for an audience is an enormously satisfying endeavor. What a good narrative in a game allows us to do is to participate in this experience on our own, without the aid of others. We take on one role, just as we would onstage, and trust to the game’s designers to carry the rest.

Much has been said in games criticism about how the player is simultaneously creator and audience, something which is true in no other medium — but I would add that if any other medium comes close, it’s the theater. Onstage, one can participate in a story which unfolds in real-time and which has no “post-production.” The only line drawn between the creators of a stage production and the audience is one which is invisible, hypothetical, mutually agreed upon, and respected by all parties involved (or not!).

Playing a game is like having that fourth wall removed, being invited up from the audience to participate, and immediately knowing all of the lines. What a wonder! Is it so surprising, then, that some of us gamers are perfectly willing to abandon our agency if it’s in service of the production as a whole?

I think that those of us who consider games critically ought to be more cognizant of the parallel between games and the stage — it strikes me as a more apt comparison than games and cinema. It might behoove game designers, as well, to consider this comparison when thinking about matters of player agency in their design. If we think about the roles that we’re taking on as gamers, we might be inclined to play differently — and the experience might even be improved!(source:venturebeat)

闽公网安备35020302001549号

闽公网安备35020302001549号