阐述以“技能抽象化”平衡游戏设计的方法

作者:Josh Bycer

题材的合并是游戏设计演变的关键领域。《神秘海域》系列游戏结合了射击、解谜和冒险元素。

除了拓展游戏可玩性之外,这还实现了另外一个目标——让游戏能为更多人所接受。

最难结合的两个题材是动作游戏和RPG游戏。其原因在于,这两种游戏的抽象化技能以及每类游戏处理这些元素的方法各不相同。可以用“技能抽象化”这个术语来概括这种情况,这个术语的定义是:玩家技能(游戏邦注:或输入)影响游戏可玩性的程度。

在两个题材初期,它们本就是两个对立的极端。随着时间的推移,两种题材的游戏设计慢慢朝中间移动。动作游戏中添加了更多的RPG元素,RPG游戏也变得更为动作化。

一方面,这使得两个题材可以接触到更多的玩家。但是,正如林肯所述:“你无法同时取悦所有人。”

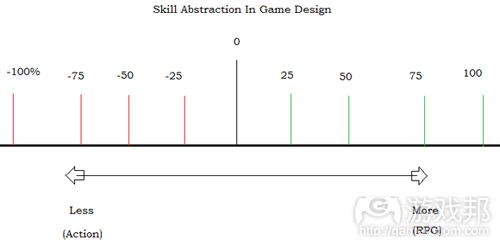

在我们深入探讨这个方面之前,先看看这张展示此类抽象化的图表:

1、100%指完全没有抽象化技能的游戏。在这些游戏中,打通游戏的惟一决定因素是玩家的技能。比如,早期的射击游戏并没有游戏内置精确度这个概念,只要你的光标对准了敌人,你就可以打中他们。街机时代里盛行的枪支游戏是另一个绝佳的范例。决定胜利或失败的惟一要素是玩家能否用枪支瞄准目标。

2、75%的是现代射击游戏,现在角色的精确度和移动对游戏结果会有一定的影响。你不能期盼角色在奔跑和跳跃时还能够精准射击,这也提升了游戏场景中掩体的重要性。技能仍然非常重要,但是现在玩家必须平衡自身的技能和角色身上的其他要素。

3、50%是指那些枪支间有所差异的射击游戏。《潜行者》、《使命召唤》和《军团要塞2》之类的游戏中有着多种多样的武器。在《潜行者》中,有多种手枪、散弹枪和突击步枪,这些枪支的差别不仅仅在于样式上,枪支之间的伤害和精确度等因素都有所不同。即便某些玩家可能是神枪手,如果他们所使用的枪支精确度很低,那么他们可能也无法集中敌人或者对敌人造成足够杀死他们的伤害。

《军团要塞2》便采用了这种概念,其中所有的装备均是如此。不同的枪支有不同的效果,这使得玩家在角色类型的选择上需要考虑更多内容。

4、25%近期的流行要归功于《无主之地》。这款游戏被称为“角色扮演射击游戏”,游戏中的武器系统与上述50%类型的游戏相同。在战斗中集中攻击敌人的弱点能够造成更多的伤害。关键的差异之处在于,现在玩家的经验等级融入了游戏战斗系统。

等级系统的作用方式如下:如果玩家的等级与敌人相同,那么双方的所造成的伤害没有任何变化。如果玩家的等级较高,他们会得到伤害加成,而敌人在攻击玩家时会受到伤害惩罚。如果玩家的等级比敌人低,那么效果就是相反的。

在该系列的另一端:

1、100%抽象化。首款CRPG和桌面游戏就属于这个类别。在这些游戏中,向他们的同伴或角色发出命令是玩家同游戏的惟一互动方式。因而,计算公式以及玩家角色和敌人的属性决定了战斗的结果。

2、75%是《魔兽世界》或《无尽的任务》等MMO游戏的标准战斗模型。玩家可以在动作类游戏中控制角色的移动,但是所有的战斗以及同游戏世界的互动被游戏所抽象化。

玩家仍然被限制只能向他们的角色发出命令,然后等待命令的结果,但是节奏比100%的游戏要快,因为双方是在同时施展动作的。

3、50%的游戏设计中融入了更多的动作元素,就像《巫师》首作那样。玩家可以自由控制角色,而且这会对战斗的结果产生更大的影响。

在《巫师》中,玩家可以控制鼠标点击的时机来形成基本连击。多数的设计仍然是抽象的,角色的属性、武器和等级依然是影响战斗结果的主要因素。

诸如马里奥RPG系列游戏等JRPG也采用了这种方式。玩家可以在战斗中使用定时道具来影响他们的攻击和防御能力。战斗仍然是抽象化的,玩家的状态和装备才是决定因素。

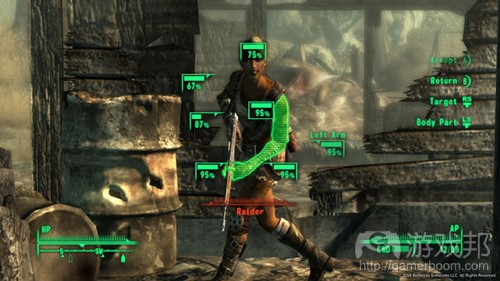

4、25%指代某种特别形式的RPG游戏。这种类别包括《Gothic》系列的欧洲RPG游戏,以及Bethesda Softworks旗下流行游戏《上古卷轴》系列和《辐射3》。在这些游戏中,玩家像在动作游戏中那样控制自己的角色。战斗是实时进行的,需要玩家像在动作游戏中那样躲避炮弹,同时锁定敌人发动攻击。一旦玩家施展动作,游戏将呈现出抽象化的结果。

在《辐射3》中,一旦玩家用枪口对准敌人并开火时,便会有许多因素参与到这个过程中:角色使用该种枪支的技能以及枪支本身的精确度两者都会决定子弹是否命中敌人。一旦子弹命中敌人,敌人的抗性和护甲决定了玩家究竟可以造成多少伤害。

对于如何应付各种情形,玩家可以有各种选择,比如说服某些人帮助他们等。但是,一旦行动被选择,剩下的其他事项都由角色的状态来决定。比如,直到玩家获得足够高的开锁技能时,《辐射3》中的解锁小游戏才会开启。

在我们讨论图表上的0%游戏类型时,先指出两类25%游戏的相似点很重要。在移动和战斗方面,两类游戏都给予玩家一定的自由。不同之处在于,将游戏的哪个部分进行抽象化。我们所举的《辐射3》和《无主之地》这两个范例都将武器伤害和敌人所受到的伤害进行抽象化。不同之处在于,《无主之地》的影响需要玩家的技能,而《辐射3》只需要玩家瞄准敌人即可。

当我们到达图表中0%这个位置时,两种题材之间的界限变得模糊起来。《巫师2》或《质量效应》三部曲的发展趋势正属于此类。在这种情况下,对题材的传统描述已经不足以描述这些游戏。

《巫师2》在设计中贯穿了技能和抽象化两个层面。在战斗过程中,玩家可以完全控制主角Geralt。在玩家发动攻击时,无论使用的是剑、道具还是魔法,游戏都会通过计算来决定玩家造成多少伤害。Geralt的大部分能力通过等级系统进行锁定,比如为咒语添加更多的功能或者反击的能力等。

角色升级后,玩家可以选择提升何种技能,由此来影响角色在战斗中的能力。在对话过程中,游戏将选择不同谈判选项(游戏邦注:如威胁或意识控制)的结果抽象化。如果成功,这些技能的等级就会得到提升,增加将来该选项使用的成功率。战斗是游戏玩法的主体部分,同时与游戏中各种角色的互动决定了情节的发展路线。

对于《巫师2》或者《质量效应3》之类的游戏,我们要把它们称作含有RPG元素的动作游戏,还是含有动作元素的RPG游戏呢?

通过对设计方法的深化,开发商和发行商们正努力实现制作出尽量接近0%游戏的梦想。但是,随着设计师逐渐远离两个极端,他们会面临疏远核心用户的危险。

多亏了这些成为主流的游戏,这一行业才发生了相应的改变。核心玩家,或者说那些想要得到-100%或100%抽象化游戏的玩家,不再占多数。反而,他们多数人都转入开发商瞄准的细分市场,多数AAA游戏正可以满足他们的诉求。

多数基于技能的游戏瞄准的是-70%到-50%的人群,同时RPG游戏关注的是70%到50%的人群。差异立马显现出来:这些粉丝并没有离开游戏,但相对于那些更为主流的游戏的粉丝来说,他们只能算整桶水中的一滴而已。

当开发商和发行商看到《使命召唤》、《质量效应》或《上古卷轴》系列游戏登上最畅销游戏排行榜而且获得各种奖励时,肯定会被大受诱惑,导致他们争先去创造符合所有人诉求的游戏。但是,这篇文章若还能够给你一点启示的话,那就是:你无法制作出受到所有玩家欢迎的游戏。

从设计角度上来说,你不可能创作出100%依靠玩家技能同时将角色互动完全抽象化,并且能够吸引所有玩家的游戏。

重视技能的玩家不希望通过提升等级才能让他们的爆头对敌人产生伤害。相比之下,RPG粉丝希望战斗的结果由他们角色的能力来决定。必须有所让步,在游戏中必须有某个方面处于主要的位置。而当出现这种情况时,总是会有某些人感到不高兴。

作为移向0%的设计师,他们需要认识到的是题材惯例和机制要么不适合加入游戏中,要么就需要做出改变。-100%游戏的UI不需要过于复杂。《子弹风暴》中,屏幕只呈现生命值、弹药容量和分数的信息。随着越来越多的抽象化被增添到设计中,就需要重新对UI进行设计以容纳这些内容,比如准心指示器和库存界面等。

如果抽象化较少,RPG游戏中的一方的严格控制变得较为困难。当所有的事件都是实时发生时,玩家就无法及时做出同样复杂的指令。这需要设计师给予游戏中各方更多的AI控制权,或者改变玩家在战斗期间的地位,从战略制定者转变成战士。

另一个挑战是,玩家对各个题材都有所期待。动作游戏以尽量简洁简单的方式来呈现信息,保证玩家总是处在行动中。但是,RPG游戏中对属性和信息的管理是必要的,玩家想要放慢速度来细心研究数据。随着设计逐渐趋向0%,需要对这两种不同的看法进行处理。如果做法不当的话,会得罪两个题材的粉丝。

以《巫师2》为例,为了寻找与设计RPG方面相关的信息,比如他们对话选项的等级,玩家需要浏览至少3个不同屏幕的信息。这放慢了游戏速度,与激烈的战斗有显著的差异。

而《潜行者》系列游戏开发出了完美平衡动作和抽象化的UI。库存/状态屏幕向玩家提供所有他们需要的有关角色的信息,包括武器的细节。在这里玩家可以找到他们需要的结果,做出些改变,然后尽快地回到行动中。

主流游戏设计已经成为了一场有关两个极端粉丝(游戏邦注:或核心玩家)注意力的拔河游戏,同时扩展了游戏所满足的玩家的诉求。如果一边拉的力气过大,你得到的将是能够让粉丝高兴但吸引力有限的游戏。如果过于偏向另一边,设计师会处在更加糟糕的境地,粉丝很容易便可以体验到游戏的乐趣,但是却很难吸引到更多的玩家。

游戏目前已经进入主流媒介领域,与之前漫画和摇滚音乐的情况类似。在这种新的情况下,维持新旧粉丝平衡的责任就在于设计师身上。(本文为游戏邦/gamerboom.com编译,拒绝任何不保留版权的转载,如需转载请联系:游戏邦)

The Abstraction Of Skill In Game Design

Josh Bycer

One of the key areas of evolution in game design has to be the merging of genres. Games like the Uncharted series combine shooting, puzzle, and adventure elements together.

Besides expanding the gameplay, this serves another purpose; it opens up the game to more people.

Two genres that have been working the hardest to do this would be action games and RPGs. The determining factor is the abstraction of skill and how each game handles it differently. This has lead to the term “skill abstraction.” It’s defined as: The degree of which player skill (or input) has an effect on the gameplay.

In their infancy, both genres existed on complete opposite ends of the spectrum. Slowly, over the years, games designed for both genres have been moving inward. Action games have been adding more RPG elements; RPGs have become more action oriented.

On one hand, this has opened up the respective genres to more gamers. However, to quote Abraham Lincoln, “…you can’t please all the people, all the time.”

Before we examine this, here is a chart showing this abstraction:

-100 percent refers to games with zero abstraction of skill. These are games where player skill is the only determining factor in beating the game. For instance, early shooters didn’t deal with the concept of in-game accuracy; if your cursor was on the enemy, you were going to hit them. Gun games, popularized in the arcade scene, are another great example. How well the player can aim the gun and prioritize threats were the only factors that separated victory from defeat.

-75 percent brings us to modern day shooters, where factors like the characters accuracy and movement now play a role. You can’t expect your character to fire well while running and jumping, this also gave rise to the importance of cover. Skill is still important, but now the player must balance their skill with the additional factors of the character.

-50 percent is where all guns are not created equal. Games like Stalker, Call of Duty, and even Team Fortress 2 feature a variety of weapons. In Stalker, there are multiple pistols, shotguns, and assault rifles, but they are not only differentiated by type. Guns vary in terms of how much damage they do, their accuracy, and so on. Even though the player may be a crack shot, if their gun has poor accuracy, they may not be able to hit enemies or do enough damage to kill them.

Team Fortress 2 has embraced this concept, with all kinds of equipment available. Different guns for the classes have different effects, and give the player more options on their classes’ load-out.

-25 percent has been recently popularized thanks to Borderlands. Billed as a “role playing shooter,” the game features the same kind of weapon diversity seen in games at the -50 percent mark. Combat is still twitch-based, and getting a hit on the weak spot of an enemy will cause more damage. The key difference is that now the player has their own experience level to contend with.

The leveling system works like this: if both the player and enemy are the same level, then there are no modifiers done to damage on either side. If the player is a higher level, they will receive a damage bonus based on the difference in levels, and the enemy will receive a damage penalty when attacking the player. The effects are reversed if the player is a lower level compared to the enemy.

The other end of the spectrum:

100 percent abstraction. The first CRPGs and tabletop games fall into this category. Here, the only interaction the player has with the game is issuing orders to their party or character. From there, equations and the character’s and enemies’ attributes determine the outcome of the battle.

75 percent is the standard combat model for MMOs like World of Warcraft or EverQuest. Players can control the movement of their character as in an action game, but all combat and interacting with the world is abstracted by the game.

Players are still restricted to just issuing commands to their character and then watching how everything plays out, but at a quicker pace then the 100 percent titles, due to both parties performing their actions at the same time.

50 percent is where more action elements begin to seep into the design, as evident in games like the first The Witcher. Players can control their characters freely, and this has a greater impact on how combat plays out.

In The Witcher, they can time mouse clicks to form basic combos. Most of the design is still abstracted; the character’s attributes, weapons and level are still the prime factors in how combat plays out.

Many JRPGs, such as the Mario RPG series, have also gone this route. Players can influence their offensive and defensive abilities with timed button presses during combat. Combat is still abstracted, with the stats and equipment of the characters the determining factor.

25 percent titles cover a very specific type of RPG. This category includes European RPGs like the Gothic series and has been popularized by Bethesda Softworks with The Elder Scrolls series and Fallout 3. In these titles, the player controls their character much in the same way as in an action title. Combat is real-time, requiring the player to dodge projectiles as they would in an action game, while targeting enemies with their attacks. Once the player makes an action, whether that is firing a pistol or trying to pick a lock, the game abstracts those results.

In Fallout 3, once the player has their gun lined up with the enemy and fires, several factors come into play: the character’s skill with the type of gun and the accuracy of the gun itself both determine if the bullet hits. Once the bullet hits, the enemies’ resistances and armor determine how much (if any) damage is actually done.

The player has a variety of choices on how to handle situations, such as convincing someone to help them, or picking a lock. However, once the action has been selected, the rest is up to the stats of the character. For instance, the lock picking mini-game in Fallout 3 is not accessible unless the player has a high enough lock picking skill to begin with.

Before we talk about 0 percent on the chart, it is important to point out the similarities between the two 25 percentile groups. Both types of titles give the player freedom when it comes to movement and setting up combat. The difference is where the abstraction comes into play. Both of our example games, Fallout 3 and Borderlands, abstract damage based on the weapons fired and who is being attacked. Where they diverge is that Borderlands relies on player skill to the point of impact, whereas Fallout 3 is requires only that the player lines up the shot.

As we move to 0 percent on the chart, the lines between the genres begin to blur. Games like The Witcher 2 or the ultimate direction of the Mass Effect trilogy are examples of this. At this point, the traditional description of the genre is not enough to describe these games.

The Witcher 2 uses both skill and abstraction throughout its design. During combat, the player has complete control of the main character, Geralt. Whenever the player lands a hit, either by sword, item, or magic, the game will run calculations to determine how much damage was done. The majority of Geralt’s abilities are locked behind the leveling system, such as adding more functionality to his spells, or the ability to counterattack.

Leveling up allows the player to choose which skills, or traits, to improve which will affect his abilities in combat. During conversations, the game will abstract the results of choosing different negotiation options like threatening or mind control. These skills will level up on success and increase the success rate for future choices. Combat is where the bulk of the gameplay is, while the interactions with the characters of the world determine how the plot plays out.

For a game like The Witcher 2, or with how Mass Effect 3 is shaping up, do we refer to them as action games with RPG elements, or RPGs with action elements?

By casting a wide net with their designs, developers and publishers are chasing the dream of creating games as close to 0 percent as possible. However, as designers move away from the extremes, they risk alienating their core audience.

Times have changed in the industry, thanks to games becoming more mainstream. Core gamers, or the ones who want either -100 or 100 percent abstraction, are no longer the majority. Instead, they have for the most part been moved into a niche market, as most triple-A titles are aiming for greater appeal.

Most skill-based games are aimed at the -70 to -50 percent crowds, while RPGs are aimed at 70 to 50 percent. A distinction has to be made: it’s not that these fans are going away; instead, they are a drop in the bucket compared to the fans of more mainstream games.

When developers and publishers see series like Call of Duty, Mass Effect, or The Elder Scrolls on the top of the bestsellers list, and recipients of numerous awards, that has to catch their attention. This has led to the challenge of creating games that appeal to everyone. However, if there is one lesson to take away from this article it is this: You cannot make a game that has universal appeal.

Design-wise, it is impossible to create a game that relies on 100 percent player skill and at the same time completely abstracts character interaction and expect it to appeal to everyone.

Skill-based gamers don’t want to have to grind levels so that their headshots will do damage. Conversely, RPG fans want their character’s dexterity, not their own, to determine outcomes. Something has to give; one side has to be given priority in the game space — and when that happens, someone is not going to be happy.

As a designer moves closer to 0 percent, they need to realize that genre conventions and mechanics will either not fit, or have to be altered. A UI for a -100 percent game doesn’t have to be complex. With Bulletstorm, the only information on screen is health, ammo capacity, and score. As more abstractions are added to the design, the UI needs to be redesigned to accommodate them — such as an indicator for accuracy, and even an inventory screen.

Strict control of a party in a RPG becomes harder with less abstraction. A player simply cannot give the same complex orders when everything is real-time. This requires the designers to give more AI control to the party, or change the player’s role during combat, from tactician to fighter.

Another challenge is that players have expectations for the respective genre. Action games are about presenting information as cleanly and easily as possible to keep players in the action. On the other hand, in a RPG where managing attributes and information is necessary, the player wants to slow down and examine the data. As the design moves to 0 percent, these two polarizing views will have to be dealt with — and if it isn’t done right, it will annoy fans of each specific genre.

Take The Witcher 2, as an example, in order to find information relating to the RPG side of the design, such as the level of their conversation options. The player has to go through at least three different screens’ worth of information. This slows the game down dramatically, and is a sharp contrast to how responsive combat is.

The Stalker series, on the other hand, developed a UI that achieves a greater balance between action and abstraction. The inventory/status screen gives the player all the information they need about their character, including details on their weapons. This allows players to find what they’re looking for, make any changes, and get back to the action as quickly as possible.

Mainstream game design has become a game of tug of war between keeping the fans (or core gamers) happy, while expanding the appeal of the game with the designers caught in the middle. Pulled too far one way and you have a game that keeps the fans happy, but has limited appeal. Go too far the other way and the designer can have a worse situation: a game that is too watered down for fans to enjoy, yet too inaccessible to attract a larger audience.

The industry is now at a point that it has entered the mainstream, much in the same way that comics and rock music have done before. In this new reality, it will be up to designers to strike a balance between old and new fans. (Source: Gamasutra)

闽公网安备35020302001549号

闽公网安备35020302001549号