观察家解析社交游戏的“红海大战”现象及其成因

游戏邦注:本文作者为Tadhg Kelly,他在文中重点讨论了社交游戏公司的“红海战略”,观察并剖析了这些公司的产品同质化、运营策略雷同的现象及成因。

本文的灵感来自于《蓝海战略》(Blue Ocean Strategy)这本书,该书作者W. Chan Kim和Renee Mauborgne在书中提出了一些方法,供企业了解自身竞争模式,并针对它们提出了全新的解决方案和开拓新市场的途径。

该书作者表示,很多公司都陷入了经济领域中的红海竞争(例如血腥的厮杀和竞争)模式。也就是说,很多时候这些企业都试图采用既有的熟悉模式与对手过招,而竞争的结果通常也惨不忍睹。在研究采用红海竞争策略公司的过程中,两位作者发现,这些公司常常学习对手的策略,有的模仿,有的则独树一帜。这似乎是采用红海战略公司的主要思考和行为方式,大家彼此处于对立状态,这样一来就会出现大量雷同作品,它们的市场营销方式也如出一辙。

书中引用的一个典型例子是美国的葡萄酒行业:葡萄酒主要有两中销售模式,即高档型和经济型,酒业公司都采用相同的要素进行竞争。高档型模式的生产商注重葡萄酒的年份、口感层次以及包装。而经济型模式的厂商虽然也注重包装,但他们并不关注口感层次,而是更多关注价格。虽然两种模式的酒商都努力让自己更具竞争力,但作者认为,这些企业凸显优势的方式大同小异。X酒获得的荣誉比Y酒多12%;A酒年份比B酒早50年。

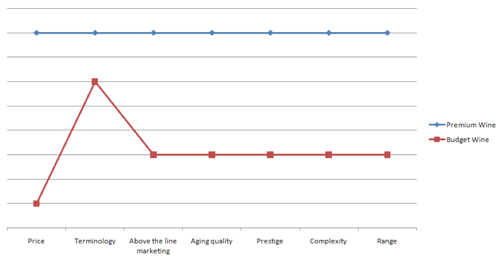

作者绘制了一个Strategy Canvas图表来说明葡萄酒行业的发展概况。横轴代表公司的多种竞争要素,而纵轴则代表酒商所获得的回报情况。

图表如下:

该书对于红海竞争市场的结论是:在这种模式中,企业争夺的是现有顾客或者现有类型的顾客。红海竞争模式只顾当前问题,但并没有应对新问题的解决方案。酒商们都在争取酒的荣誉,宣传酒的口感层次,力图招揽竞争对手的顾客。而市场上的葡萄酒老顾客也提高了品味,开始寻找更多更好的酒类,而大多数酒商们都完全忽略了非顾客群体。

Facebook游戏

我认为Facebook游戏开发商正身处一片新红海之中。虽然几年前,他们还处于蓝海地带,但很快他们就开始陷入和葡萄酒行业一样的关键要素竞争当中。游戏邦认为,虽然他们还没达到血红的地步,但也已经处在红透了的阶段。

各种开发商都推出了大量游戏,有不少重量级选手,也有一家独大的超级竞争者(Zynga)。虽然有很多小型开发商都获得了不少用户,但除Zynga之外的高端市场已经在走下坡路了,这是因为没有新对手加入市场来打破格局。从市场营销和发行渠道来看,Facebook市场似乎更垂青于财力雄厚的开发商。

但游戏邦看到,即使是规模很小的公司,也在采用与大公司一样的竞争模式。就像小酒商宣传自己的酒年代久远,口感有层次一样,小型Facebook开发商通常在效仿大公司制作的游戏。

据称这个市场上有99%的开发商都在争取同一个用户,有些公司之所以能够取得成功,纯粹是因为这一行业的发展让它们水涨船高。Facebook本身也在不断发展,所以在这种情况下,许多克隆游戏还能够维持良好的发展势头。但大高潮带来的问题是,潮水达到颠峰状态后,有许多船会搁浅触礁。

大部分的Facebook游戏都同属一个范畴。游戏邦发现,它们看起来大同小异,营销方式也趋于一致,通过同样的用户关系增加玩家的黏性,而且连品牌都很神似。和葡萄酒行业一样,游戏开发商也在以同样的路径寻求差异化发展。

如果这个观点成立的话,那么就意味着Facebook游戏之间的竞争也是遵循了某些特定模式。那么这些模式是什么呢,而这些模式对应的要素又是什么呢?

Facebook上的游戏和应用类型

一般说来,我认为Facebook游戏可以简单分为以下3种:

* 社交应用

* 休闲游戏

* 扩展游戏

社交应用在短期内可以取得很高的MAU,但据游戏邦观察,它们的DAU/MAU比值最大的时候还不到5%。早期的社交应用,例如单一的测试或者热门电影列表,早已被如今的综合型应用所取代,因为后者支持玩家自己设计和创建内容。综合型应用的生命周期比前者更长,但在DAU/MAU的表现上仍然不是很理想,它们主要通过广告或者交叉推广实现营收。

休闲游戏主要是指为单人玩家提供的游戏体验。这类游戏设有积分排行榜,但更注重的是玩家的技能。《宝石迷阵闪电战》、《Texas Hold’Em》或者Mindjolt推出的系列游戏都属于休闲游戏。它们的营收方式比较丰富,主要有积分、筹码、广告等。

扩展游戏主要是以农场、黑手党、城市或者宠物为主题的模拟类游戏。据游戏邦了解,它们大多是时间管理游戏,鼓励用户有创造性地投资,同时也推动用户参与虚拟经济活动。成功的Facebook游戏大多是扩展游戏,

这主要是因为游戏要求用户每天来访问和签到。早期的这类游戏多为以PHP创建的角色扮演游戏,但在过去2年,这个同质化的模拟类游戏才是这个领域的主力军。这类游戏还包括《Bola》和《FIFA Superstars》等体育游戏。

竞争要素

上面所谈的是策略模式,那么下面的就是竞争要素:

病毒式传播:与大家的普遍看法相同,社交游戏在病毒式传播的基础上获得了发展。这些游戏和Facebook社交关系网络紧紧绑定在一起,借助所有的免费营销渠道定期向新老用户推销自己、发布通知、发邮件、发消息等。社交游戏把病毒式传播放在第一位,Facebook游戏至少每隔5分钟都会提醒用户发布消息,让他们晒出高分或者寻求援助。

游戏设置:休闲游戏的设置最重视玩家技能,社交应用其次,而社交游戏最次。这三个种类的有趣之处在于它们的游戏设置都很相似。游戏邦发现,休闲游戏长约1分钟,动作密集,强度大(扑克游戏是个例外)。扩展游戏则主要是基于时间的活动,如消耗能量、晋级以及完成关卡任务,它既不需要策略也不需要技能。社交应用可能会有简单的测试(如小测验),旨在制造发布消息的社交传播活动。很少有游戏会超出这三个范畴。

人物角色:Facebook游戏大多比较温和,没有粗话,也没有暴力画面,只有大量甜美可爱的人物。游戏没有阴暗面,也缺少幽默感。相对于其他视频游戏来说,这是社交游戏的两个特征,但这同时也符合网站的基调和用户的国际化特点。当然和其他的游戏相比,社交游戏的人物最多只能说是符合主流文化,如果极端一点来看,它们其实很平庸。不过,这并非多数玩家关注的重点。

游戏区域:所有Facebook游戏页面规格都是:760像数(宽)X 600-700像数(高)。大多数的社交应用都是根据标准的Facebook API组件建立起来的,而游戏则是由Flash创建而成。它们之间存在许多共性,包括立体化的场景、社交好友工具栏、下侧工具栏、右侧高分图表、上侧的等级条、能量条以及纯粹的鼠标控制功能。很少有游戏曾对游戏区域进行创新,它们只是把游戏压缩到有限的空间。

营收模式:一般来说,社交游戏有三种主要的运营模式:广告赞助(价值低)、充值途径(价值中等)以及虚拟商品交易(价值高)。社交应用偏向于广告赞助模式,休闲游戏采用充值途径,同时兼有虚拟商品交易,而扩展游戏采用商品交易模式,也同时也兼有充值模式。营收方式的创新让社交游戏位居众游戏之首,投资社交游戏成为许多公司的首要电子商务活动。

品牌策略:Facebook的游戏理念从它们的名字中就可以看出一二(英国人把这称作Ronseal营销),用户顾名思义就能立刻了解游戏内容。用户对游戏的认知程度更多依靠曝光度,而非营销活动。典型的游戏品牌战略(例如依托名人效应、授权游戏、电影以及电视节目的关系)效果都不太好,同时曾经在Facebook平台上拥有极高知名度的游戏,现在也已经不怎么受欢迎。游戏邦获悉,《FarmVille》是最有名气的社交游戏品牌,但它现在并不是多数人的最爱。

广告推广:大多数公司都知道充分利用各式各样的广告渠道推广游戏。从Facebook的广告属性来看,这类广告一般具有即时性和直接性的特点,通常会有“现在加入吧”等字样。从基调来看,广告内容不会太宽泛。扩展游戏的广告推广力度比其他两者更大,这多关是因为这类游戏开发商的收益更高,他们可以承担大量的广告费用。

交叉推广:几乎所有的社交游戏都在采用交叉推广模式。一般的观点是,交叉推广是增加游戏在Facebook平台曝光度的最佳途径,因为它的定位更准确,内容的可视性更强。大型开发商很早就开始采用交叉推广模式,而后期或者小型开发商则使用Applifier或者Appstrip来提供的交叉推广服务。Facebook游戏的定位和交叉推广内容实际上都大同小异,它们一般放置于游戏界面顶端(这很好理解,因为宽度有限制),展示5、6个其他游戏的图标。社交应用的主要目的是交叉推广其他游戏,而扩展游戏则致力于让用户从一个游戏转移到另一个游戏。休闲游戏也有交叉推广的行动,但又总让人觉得它们一点儿也不希望用户离开本游戏。

奖励机制:社交应用几乎没有什么奖励机制,这也正是它们用户留存率很低的原因所在。休闲游戏是根据技能提供奖励的,这对消遣时间的用户来说还是很有吸引力的,但这种方式也存在不足,因为所有玩家迟早都会精通这些本领,除非这它们真的有很好的游戏机制,每周的高分排行榜和特殊加级赛可以弥补这点不足。扩展游戏则以时间为基本要素,要求玩家不断回来照料花园、处死黑帮大佬或者通过做类似的事情来获得更多的能量。这是个很聪明的创意,但也被很很多游戏效仿,甚至有许多开发商认为,能量和等级是维持社交游戏用户留存率必不可少的元素。

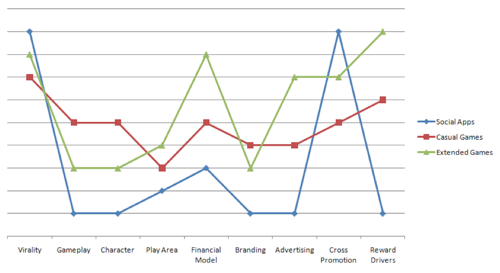

上述要素对于社交应用、休闲游戏和扩展游戏的影响如下图所示:

为什么红海战局还在扩大?

虽然Facebook游戏开发商可能会认为,有效利用玩家反馈参数可以开发出好游戏,或者开发最低可行性的产品,但事实上,他们和所有企业一样,通过都是在互相模仿中前进。公司之间相互效仿作品,这种方式速度快,成本低,因为成功的领路人已经首先承担了一切风险,然而由于害怕风险,仍有不少投资者停滞不前,等待前者的创意获得成功后再下手。我们常常可以发现,从平板电脑到上网本,再到游戏产业,整个科技领域都有这种情况。

传统智慧来自于市场先驱,无论他们的想法确实很成功,或者后来被证实是个不可行的策略,他们都已为后人开创了先河。红海的成因就是各个公司都认为他们要依照现有的模式竞争,争取现存的用户,这样一来,市场开始在“已知事物”的模式中僵化,因为大家都更愿意采纳更易理解的运营方法。

在社交游戏中,我最喜欢的是富有立体感的游戏,自从《Restaurant City》、《Farm Town》出现以来,从《FarmVille》到《Crime City》,几乎所有的扩展游戏都充满三维立体感。但如果看看《百万大富翁》(Monopoly Millionaires)等游戏,从用户的角度来说,它制作成3D游戏其实并没有多大意义。

Facebook的屏幕大小很有局限性,但却适合传播富有竞争力的游戏内容。但这些开发商为什么还要继续通过游戏画面争夺用户眼球,而不是推出更具有深度的内容呢?因为所有开发商都在这么做,其中必然有一定理由,对吧?

当然在现实世界中没有人知道这一点。这也正是蓝海思维的起因。(本文为游戏邦/gamerboom.com编译,转载请注明来源:游戏邦)

The Red Ocean of Social Games

[Editor's note: How can social game developers create unique new products? In the first of a two part series below, guest author Tadhg Kelly discusses how the social gaming industry fits into the "red ocean/blue ocean" business framework -- basically, why social games are so often copies of each other and what developers can do differently in order to succeed. He covers the red ocean aspects below, and will get into the blue ocean part in a follow-up post.]

I was inspired to write this article by Blue Ocean Strategy. In the book, authors W. Chan Kim and Renee Mauborgne explore methods that companies can use to understand how everything that their competition is doing falls into well-defined types, and then create completely new ways to overcome them and consequently new markets.

Most companies, they contend, are locked into competition with each other in the red ocean (i.e. bloody) side of the economy. This means that most of the time they are trying to compete along well-understood existing lines, and that the results of this kind of competition are angry and merciless. In studying red ocean companies, they observe how they all tend to study competitors’ tactics and then emulate or attempt to differentiate themselves. Such tactics seem to be the main way that red ocean companies think and act, as though they are at war, and this leads to a lot of very similar products created, marketed and sold in much the same way.

One particularly effective example that the book cites is the US wine industry: Wine is sold along two lines, premium and budget, and all of the participants in the market tend to compete using the same factors. Premium wine makers talk about heritage, complexity of taste and image. Budget wines also use image, but they talk less about complexity of taste and more about price. While each wine works hard to differentiate itself, Blue Ocean Strategy argues that most of it tries to differentiate itself in the same way. Wine X has 12% more medals than Wine Y,while Wine A has 50 years more heritage than Wine B.

The authors produce a diagram to illustrate the strategic profile of the wine industry, called a Strategy Canvas. The horizontal axis shows the various factors, whereas the vertical reflects the offering level for buyers (meaning the amount invested by the winemakers in the factor, or the price to the buyer).

Their wine canvas looks something like this:

The book’s conclusion about red ocean markets is that they are a result of focusing on competition for existing customers, or existing types of customer. Red ocean companies offer better solutions for existing problems rather than alternatives solutions for new problems, so wine makers try to win medals and plaudits for the complexity of their product in order to win existing customers away from their competitors. Their customers, consequently, are educated enough in wine to look for more and better of those traits, and wine makers by and large ignore non customers entirely.

Facebook Games

I think that Facebook game developers find themselves in a newly red ocean. While it was blue in all directions a few years ago, increasingly it has become dominated by key factors and competition that are analogous to the wine industry. It may not be blood red yet, but it is certainly a reddish purple.

There are a lot of games from a lot of developers, some heavy hitters, one huge hitter in particular (Zynga). While many of the smaller developers (championed by Inside Social Games and others) certainly have grown to interesting audience sizes, the top of the end of the market outside Zynga has actually been declining for a while, with no obvious new competitor to shake things up. The Facebook market seems to reward financial muscle more than anything else in terms of raw marketing and distribution power.

Yet at the same time even the smallest developers are competing along much the same lines as the big boys. Like small wine makers talking up their own heritage and complexity, smaller Facebook developers commonly make games that are very similar to those of their larger brethren.

99% of the developers in the market are convinced that they are hunting after the same customer, and most of the successes are happening purely because the tide is still rising. Facebook itself is still growing, so in those conditions many clone games will still do well. A rising tide may raise all ships, but the problem with high tides is that they do eventually peak, leaving many boats stranded on the rocks.

Most of the games in the Facebook ocean are virtually identical as a product category. They look identical, are marketed the same way and try to engage the player in the same sort of relationship. They are also branded very similarly. Like wine, they seem to be trying to differentiate in the same way.

If true, then that would mean that Facebook games are also competing along well defined lines. So what would the lines be on the Facebook canvas, and what would the corresponding factors for those lines be?

Types of Games and Apps on Facebook

Broadly speaking, I think Facebook games fall into three easily-understood lines:

* Social apps

* Casual games

* Extended games

Social apps can achieve very high MAU for short periods of time, but even at their height they rarely see more than 5% DAU/MAU engagement from users. Early social apps featuring a single quiz or a top-movies list have long since given way to aggregator applications that allow users to create their own content. Aggregator applications are much more sustainable than their forebearers, but still pretty un-engaging on a DAU/MAU basis. They primarily monetize through advertising or cross-promotional activities.

Casual games are games which are meant to serve as single-play experiences. They may retain high scores, but their focus is largely based on skill. Bejewelled Blitz, Texas Hold’Em or the variety of games offered by Mindjolt are all in the casual ballpark. They monetise with a combination of virtual goods for things like chips, play bonuses or advertising for the game aggregators.

Extended games are the farm, mafia, city and pet simulators. They are the largely time management games that encourage players to creatively invest in them, but also meter play out to encourage virtual economy participation. Most of the very successful games on Facebook are extended games, mostly because they invite a considerable quantity of daily visits and just- checking-in behaviour. Early versions of this kind of game were PHP-built role-playing games, but in the last 24 months they have moved over into isometric sim games instead. This category also includes sports sims like Bola and FIFA Superstars.

Factors

So if those are the strategic lines, then perhaps these are the factors:

Virality: Social games, goes the conventional wisdom, are built on virality. What this pretty much means is that they are hooked into the Facebook graph, and they use whatever free marketing channels are available to publish, notify, email or otherwise message new and existing users on a constant basis. This makes virality a high priority for all social applications, and virtually every game on Facebook prompts its users to Publish at least once every 5 minutes, usually to announce a high score or ask for help.

Gameplay: Casual games use skill-based gameplay the most, social apps the least, and extended games are somewhere toward the bottom of the middle. What’s interesting within these three categories is how similar the gameplay is. Casual games will typically have a minutes-length gameplay with tight actions and dynamics (Poker may count as a bit of an exception here).

Extended games are entirely based on timed activities such as spending energy, acquiring levels and completing gated tasks, requiring neither strategy nor skill. And social apps may have a simple test (like a quiz) with the objective of creating a socially relevant viral publishing action. There really are very few games outside those types.

Character: Facebook games are almost universally friendly. There is no bad language, no violent imagery, and a surfeit of cute characters. They generally have no dark side, nor much of a sense of humour. Both are unusual traits in comparison to many other kinds of video game but may well make sense given the tone of the site itself and the international nature of its audience. Certainly in comparison to many other kinds of game, the character of social games could at best be described as mainstream, or at worst bland. Regardless, it doesn’t seem to be of high concern to most of the existing players in the market.

Play Area: All Facebook games operate within a constricted page of 760 pixels width, and most are between 600 and 700 pixels tall. Most social apps are built with standard Facebook API components, while games are built in Flash. There are a very large number of commonalities across games, including isometric landscapes, social friend bars, lower action bars, right-side high scores tables, upper bar level and energy meters, and purely mouse-driven controls. Very few games (if indeed any) make innovative use of the play area, however, with games simply squashed in to the available space.

Financial Model: There are, broadly speaking, three distinctive business models in social games: Advertising (which is low value), Power-ups (medium) and Property (high). Social apps focus on the former, casual games on power-ups with some property, and extended games on property with some power-ups. Financial innovations were a big feature of why social games took off in the first place, and considerable investment is made by many companies in making sure that they are on top of their e-commercial activities.

Branding: The game concepts in Facebook are generally describable by their names (in what the British call Ronseal marketing), and require the audience to understand nothing beyond that to immediately grasp the game idea. Level of recognition is based more on visibility than through marketing stories. More typical game branding (celebrities, licenses, movies and TV shows) are mostly not effective, yet at the same time the brands that have come through from Facebook are largely not well regarded nor sought after. FarmVille is probably still the most famous social game by brand, but it’s not exactly loved.

Advertising: Most companies (thought not all) take advantage of as many advertising channels as possible. Given the nature of the Facebook advertising space, advertisements tend to have to be immediate and blunt, with a variation of a Come Play Now message. Advertising content tends not to be too broad in terms of tone. Extended games tend to feature more heavily in advertising than any other, most probably because they can afford it with their revenue model.

Cross Promotion: Nearly every Facebook application cross-promotes. Cross promotion is conventionally held to be the best way to create visibility within the platform because of the positioning and the largely visual content. Big developers learned to cross-promote early, while later or smaller developers use Applifier or Appstrip to cross promote among one another. The positioning and type of cross promotion in all Facebook games is virtually identical, consisting of a long strip across the top of the game (this makes sense because of the width restrictions) showing 5 or 6 icons of other games. Social apps’ primary purpose is arguably to cross promote into other games, while extended games have used tactics to encourage audiences to move from one game to another. Casual games cross-promote, but feel like they don’t entirely want to send users away.

Reward-Drivers: Social apps have almost no real reward drivers, which is why their retention is generally very low. Casual games tend to make rewards all around skill, which is a compelling way for many players to pass some time, but has its limits as most players will reach their maximum mastery with most casual games early unless the game has a particularly good game dynamic.

Weekly high scores competitions and special upgrades help. Extended games, on the other hand, use time as a factor to make players wait, obliging them to keep returning to tend their gardens, kill mob bosses or perhaps acquire more energy to do more of the same. It’s very clever, but also copied by many games in an identical fashion to the point that energy-and-levels are regarded as de-facto parts of making social game retention work.

The result is something like this:

Why Has the Red Ocean Developed?

While Facebook developers may talk a good game about using metrics to validate users and develop minimum viable products, the reality is – like most businesses – they tend to just copy each other. It’s simply faster and cheaper for companies to ape each others’ products where possible because successful standard bearers take all the risk, while more risk averse investors simply hang back and wait to see what’s a proven idea or not. We see this all time in technology, from tablets to netbooks, and also in games.

Conventional wisdom forms around the leaders in the market, and the choices that they make become baked in regardless of whether they actually are a good idea or not, nor whether later metrics then tell the developers that the idea doesn’t actually work. Red oceans develop because companies become convinced that their job is to compete along existing lines and for existing customers, so the market tends to calcify around certain ‘known knowns’ because it makes the business easier to understand.

In social games, my favourite example of this is the use of isometric perspectives. Since Restaurant City and Farm Town, almost all extended games from FarmVille to Crime City have incorporated isometric perspectives to give a sense of three dimensionality to their games. But if you stop and look at some of the more silly examples, such as Monopoly Millionaires, it simply makes no sense from a user perspective.

The Facebook environment is the most constricted in terms of screen real estate, and the most competitive in terms of distracting content around a game. And yet these developers go ahead making isometric games in which the players cannot see any meaningful amount of game real estate. Why? Because that’s just what everyone does, so there must be some reason to do it that way. Right?

In the real world of course, nobody knows. And that’s where Blue Ocean thinking first begins.(source:insidesocialgames)

闽公网安备35020302001549号

闽公网安备35020302001549号