分析单人模式电子游戏的局限因素

作者:Jason Rohrer

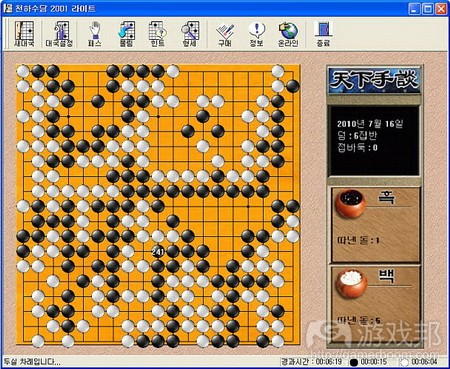

围棋常被视作是由简单基本机制衍生深刻玩法的典范。玩家掌握游戏规则只需不到1分钟,但要花大半生探究游戏深度玩法。围棋是款能够持续回访的游戏。它总是能够向玩家呈现新内容,永不过时。

艺术游戏或现代电子游戏要像围棋那样通过简单设计获得深入玩法是件难事。无限重玩价值?这几乎闻所未闻。在磨破手指终于可自由驾驶游戏(《几何战争》),找到所有收集品,或学会如何巧胜AI(《星际争霸》)后,你未来是否还会继续返回游戏,从中寻找潜在价值?

那么电子游戏哪里出错?行业经验告诉我们要赋予玩家有趣选择,我们真的有这么做,但为什么还是以失败告终。我们难道不能效仿国际象棋、黑白棋和西洋棋之类的棋盘游戏?当然可以,而且我们也这么做。这些游戏似乎大多都基于若干连锁机所创造的有趣选择。所以,我们在电子游戏中添加若干连锁机制,但我们发现这机会无法起到深化玩法的作用。我们设计有层次的机制,但似乎都缺乏深度,这些内容都无法促使玩家持续思考和学习。

那么《俄罗斯方块》呢?这是款玩家能够持续回访的电子游戏。玩家无法达到最佳状态,游戏随关卡的升级而加速,创造无尽肢体和心智挑战。但逐步加速似乎不是玩法深度的关键;这是众多电玩游戏为创造持续挑战所采用的典型伎俩。学习体验《Centipede》与学习如何操控更多小球类似。

姑且将《俄罗斯方块》中的时间因素移除,假设玩家在放置方块前可以进行无时间限制的思考。游戏缺乏反应挑战还会是款有趣游戏吗?我得还是。所出现方块的随机性及优化问题确保每个全新游戏回合都是新鲜智力挑战。如果去除随机性元素会怎么样?假设每个《俄罗斯方块》回合都以相同顺序呈现系列方块?这留给玩家的只是单一的优化问题,玩家需在随后的游戏中进行反复尝试。我相信此改变会损害《俄罗斯方块》的玩法深度,将其变成单纯求分数的谜题游戏。在找到放置系列方块的最佳方式后,你很快就会丧失兴趣。

那么什么是关键要素?随机性?但诸如围棋之类的经典棋盘游戏并未融入任何随机元素。但纸牌游戏《Solitaire》有:每个新游戏回合都提供新顺序的纸牌,创造新鲜智力挑战。大家可以在不失深度的情况下体验众多回合的《Solitaire》。

《Solitaire》最终解答有关深刻玩法的谜题。为什么《Solitaire》需要随机性,而围棋不需要?《Solitaire》、《Centepede》、《时空幻境》及其他上面提到的电子游戏与《俄罗斯方块》存在什么共同之处?

这些都是单人游戏,虽然所有深刻棋盘游戏都基于多人模式。其实多数电子游戏都是单人游戏。Raph Koster发现单人传统主要源自技术限制;例如,早期电脑无法实现网络连接。Koster把焦点放在单人游戏缺乏人与人的交流,但缺乏深刻机制的游戏还是一样有趣。

所以是双人模式令我们能够从围棋的简单机制中挖掘出无限玩法深度。但多人模式不只是能够像升级内容那样添入游戏的要素。相反多人模式更像是肥沃的土壤,其中所有玩法机制都能够发展成独特而意外的内容。游戏规则就像DNA,而潜在玩法的蔓延空间就像最终生成的有机体。缺乏多人模式,即便是最复杂的游戏机制都会变得发育不良,无法绽放。

那么单人电子游戏存在什么元素?基于速度的肢体挑战,随机性,谜题,角色前进和故事发展——真正有趣玩法的讨厌替身。

艺术游戏尤其推崇单人传统,围绕故事的主流故事亦是如此(游戏邦注:这类内容也倾向追求艺术目标)。我们是否借助其他媒介(这从根本来说都是单玩家视角)陈述瞄准艺术的作品应如何为用户所享有?我们可以自己享受绘画、雕刻、电影、书籍、戏剧和音乐。我们最后会同同伴讨论内容,但同伴不是艺术体验的必要元素。若你孤身一人在荒岛,你依然能够从这些作品中得到深刻感受,虽然换作围棋,你的收获不会太大。

若你试图收集单人非电子游戏,就会发现几乎不存在这类内容。一方面是上述《Solitaire》纸牌游戏,游戏通过随机性创造深度。另一方面是各种形式的《孔明棋》;无随机性,但具有较难的优化问题,就像系列方块出现顺序确定的《俄罗斯方块》。若你曾在《孔明棋》中胜出过,那你就完整感受过游戏的深度,因为只要你能够记住制胜的移动顺序,未来你便能够在每回游戏中获胜。

那么这是否就是单人游戏的最高心智挑战水平?融入长到而无法记住的谜题?单人游戏是否就是这样?纸牌游戏《Solitaire》和魔术方块的根本区别在哪里?回到电子游戏,融入时间挑战的《俄罗斯方块》如何转变方向,不再是个谜题?在魔术方块中融入时间限制能否将其变成一款游戏?

我早先提到的电子游戏就是个典型例子。《星际争霸》及其他即时、非即时策略游戏都未受制于类似的深度局限,即便是在单人模式中。但这些游戏的“单人模式”包含什么元素?AI对手——由电脑控制的额外玩家。虽然这些游戏以玩家&玩家对抗时存在的无尽深度著称,但游戏机制依然能够在玩家同AI对抗时发展成有趣玩法。若你能够找到助你获胜的AI弱点,那单人模式的深度就消耗殆尽。在这种情况下,问题在于这类游戏的AI尚不够成熟。

关于AI的讨论说明,人类因素不是促使简单游戏机制发展的内容。促使游戏出现美妙复杂性和巧妙玩法的不是人类赋予游戏的内容,而是相互竞争玩家所创造的火花。即便如此,没有什么比得上同好友共同体验游戏,但社交趣味及看到好友个性从玩法中显现不是创造围棋类游戏深度玩法的根本要素。围棋的深度同游戏玩家的特性无关,它就像是两个对立实体置身有待探索的宇宙空间。

但现代单人电子游戏几乎都放弃在游戏中融入AI功能。是的,多数3D游戏都将敌人同基本路线探索、规划和随机行为绑定,但这都无法匹敌国际象棋中的AI。这些主流AI都试着模拟可信人类行为,未提供对手,供玩家挖掘游戏机制的深度。

关于AI的讨论是引出本文话题的最后铺垫,也就是:

我们能否制作无AI,无随机性,无肢体挑战,融入类似《围棋》玩法深度的单人游戏?

是否存在呈现类似玩法深度的单人艺术游戏?

我现在坚信答案是“没有”。理由体现在玩家在这类游戏中的获胜方式(游戏邦注:或是争取杰出表现的方式)。若存在唯一最佳获胜路线,那么有条不紊地寻找此路线就是游戏的主要任务。只要找到相应路线,运用于将来的探索,那游戏的深度就完全丧失。若存在多个潜在获胜路线,那么找到某路线后继续探索其他路线就是选择性操作,是挖掘机制深度的体现。

所以这就是我对于此问题的答案。但此答案无法阻止我制作这类单人游戏。

我试着制作颇具深的单人抽象策略游戏。我借助成功参数,因为二元胜/负条件太像直白的谜题。

我在设计过程中的主要发现是挖掘单人机制的深度是件非常困难的事情,即便只是一丁点的深度。我试验许多潜在机制,但结果或是带来较多分数的退化情况,或是带来理想分数的琐碎策略。即便去除这些问题,我还是看到在游戏中运作良好,但无法通过修改进行完善的策略。添加更多玩法层次无法对玩法起到促进作用。最后,在发现存在深度的机制后,则需移除其他机制,给此有趣机制腾出空间,让其尽情绽放。

这似乎同我设计双人游戏(其中我可以通过限制陈旧机制获得众多玩法深度)的经验形成强烈对比。围棋经典的简单特性似乎是个特例,但深刻、简单、多人机制与其说是例外,不如说是规律。例如,就与围棋类似的设置而言,还有其他类似深度的更简单游戏,如五子棋和《Hex》。

在设计过程中我发现,几乎任何失败的单人游戏都能够在双人模式中立即起死回生。退化的琐碎高分策略会因对手找到反击方式而消失。

我将自己依此设计的一款游戏称作《i45hg》,就会变得非常有趣(游戏邦注:至少在短暂的体验过程里)。游戏体验更倾向因优化谜题而非真正体验过程而受损。只要找到合理的探索方式,你很快就会丧失兴趣。我目前获得的最高分数是84。

《i45hg》的规则

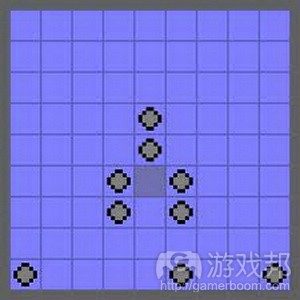

在每回合体验中,你需将9个白石放置于空旷的蓝色方框中。放置完石头后,也许还收回及替换若干前些回合的白石,点击绿色箭头就能够提交操作。在提交过程中,会出现各种转换,积分出现相应调整。然后玩家就可以步入下个回合,再放置9个白石。提交操作存在如下3个规则:

1. 白石靠近1个或多个黑石就得1分。

2. 周围白石少于3个的白石就会变成黑石。

3. 周围有3或4个黑石的方框将从游戏中消失(取而代之的是空白的无用方框)。

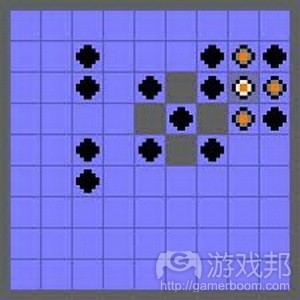

在玩家提交前,游戏会呈现有关操作结果的提示。例如,会因规则2而变黑的白石会被标上灰色。

会因规则3而遭移除的方框将被替换成空白方框。

注意替换空白方框不会阻碍你放置白石。

能够换来积分的白石标有橙色。游戏会呈现相应提示。8个白石将变成黑色,所以它们标有灰色。6个白石,包括4个标有灰色的白石,存在黑石邻居,所以此回合玩家将在操作完毕后获得6分。此回合后,4个方框将拥有3个或更多黑石邻居,所以它们将被移除。

游戏邦注:原文发布于2008年8月8日,文章叙述以当时为背景。(本文为游戏邦/gamerboom.com编译,拒绝任何不保留版权的转载,如需转载请联系:游戏邦)

Game Design Sketchbook: Testing the Limits of Single-Player

by Jason Rohrer

Go is often cited as a touchstone for profoundly deep gameplay that emerges from a shockingly simple set of basic game mechanics. You can learn the rules in less than a minute, but you can spend the rest of your life plumbing the depths of this game. Go is a game that you can return to over and over. It will always have something new to show you. It will never grow old.

As simple as Go’s design is, Go-deep gameplay for art games, or even modern videogames generally, seems to be a tough nut to crack. Infinite replayability? It’s almost unheard of. After you’ve honed your thumbs until they’re pumping like well-oiled machines (in Geometry Wars), found every last collectible (in Super Mario Galaxy), or learned how to out-smart the AI (in Starcraft), can you really come back to a game in the future and find further value in it?

Where are videogames going wrong, then? Industry-wide design wisdom tells us to give the player interesting choices, and we really try to make games that do this, but somehow we’re failing. Can’t we study board games such as Chess, Othello, and Checkers and learn from them? We can and we have. It seems that many of these board games create interesting choices out of several interlocking mechanics. So, we add some interlocking mechanics to our videogames, but we see very little added depth as a result. We add layer upon layer of mechanics, but nothing seems to profound-ify our gameplay – nothing that will keep the player thinking and learning forever.

What about Tetris? There’s a videogame that you can come back to over and over. Optimal play is probably unattainable (the game is known to be NP-hard, and that’s assuming that you can see the entire future piece queue), and the speed-up as the levels progress provides an endless physical and mental challenge. But gradual speed-up doesn’t feel like the key to gameplay depth; it’s a classic gimmick used in hundreds of arcade games to create eternal challenges. Learning how to play Centipede well, for example, is akin to learning how to juggle more and more balls.

Let’s take the time factor out of Tetris – say that you get to think for as long as you want before placing each piece. Would it still be an interesting game without the reflex challenge? I think it would. The randomness of the piece queue, combined with the optimization problem, makes every new game a fresh mental challenge. What if we take out the randomization? Suppose every game of Tetris presented you with a series of pieces in exactly the same order? That would leave you with just a single instance of the optimization problem (how to best pack this particular series of objects into the well) to try over and over on subsequent games. I believe this change would sap the gameplay depth out of Tetris, changing it into a scored puzzle. After settling on the best way you can discover to pack that series of pieces into the well, you would quickly lose interest.

So is that the key? Randomization? But classic board games like Go don’t involve any random elements. The card game Solitaire does, though: Each new game offers a new sequence of cards for a fresh mental challenge. People can play thousands of games of Solitaire without exhausting its depth.

Considering Solitaire finally leads us to answer our question about deep gameplay. Why does Solitaire need randomization while Go does not? What does Solitaire have in common with Tetris, Centepede, Braid, and almost all the other videogames mentioned so far?

These are all single-player games, while all the deep board games require multiple players. In fact, the vast majority of videogames are single-player games. Raph Koster has observed that the single-player tradition stemmed primarily from technological limitations; computers were not connected together in the early days, for example. Koster’s focus was on the absence of human contact in single-player games, but the absence of deep game mechanics is just as interesting.

ng

So it’s two players that lets us wring limitless gameplay depth out of the incredibly simple mechanics of Go. But multiplayer is not just an ingredient that can be added to a game like yet another power-up. Instead, multiplayer is more like the fertile soil in which each gameplay system can grow and blossom into its unique, emergent potential. The rules are like the DNA, and the sprawling space of possible gameplay is like the resulting organism. Without multiplayer, it seems that even the most complicated systems of mechanics become stunted and never blossom.

So what do we, with our single-player videogames, have instead? Speed-based physical challenges, randomization, puzzles, character progression, and story advancement – lousy stand-ins for truly interesting gameplay.

Art games in particular carry on the single-player tradition, as do story-centric mainstream games, which also tend to have artistic aspirations. Are we using other mediums, which are fundamentally single-viewer/reader, as a model for how an artistically-meaningful work should be consumed? We can consume paintings, sculptures, films, books, plays, and music by ourselves. We tend to discuss works at length with our companions, but companions are not a necessary component of the art experience. You could still reap deep personal benefit from these works if you were alone on a desert island, though your Go set wouldn’t do you much good.

Look around for single-player non-videogames, and you’ll find that they are almost non-existent. On the one hand, you have the aforementioned Solitaire card games, which rely on randomness for depth. On the other hand, you have Peg Solitaire in its various forms; no randomness, but another NP-hard optimization problem, like Tetris with a known piece queue. If you ever win at Peg Solitaire, you have officially exhausted the game’s depth, since you can then win every future game, so long as you can remember the move sequence that resulted in a win.

So is that what single-player games are doomed to be, at their intellectual best? Puzzles with solutions that are too long to memorize? Is there even such a thing as a single-player game? How is card Solitaire in a fundamentally different class than Rubik’s Cube? Turning to videogames, how is Tetris, with the time challenge turned off, not a puzzle? Does placing a time limit on Rubik’s Cube turn it into a game?

One videogame that I mentioned earlier is actually a special case. Starcraft, and other realtime and non-realtime strategy games, are not subject to these same depth limitations, even in single-player mode. But what does “single-player mode” for these games involve? AI opponents – additional players controlled by the computer. Though these games are famous for their endless depth when played against other humans, the mechanics can still blossom into interesting gameplay when you play against an AI. You can only exhaust the depth of the single-player variant if you find a weakness in the AI that you can exploit to guarantee a win. In that case, the problem is just that AI for such complicated games is not well developed.

The discussion of AI highlights that the human factor is not what allows simple game mechanics to blossom. It’s not what humans bring to the game, but what two competing players – human or not – bring that allows the beautiful complexity and subtlety to emerge. Granted, there is nothing like playing a good game against a good friend, but that social enjoyment, as well as seeing your friend’s personality expressed through his or her gameplay, is not a fundamental component of Go-like depth. Go’s depth exists separate from the personalities that play it, like a property of the universe just waiting to be discovered whenever two entities sit down, in opposition, to explore it.

But modern single-player videogames, both fringe and mainstream, have almost completely abandoned AI as a game feature. Yes, enemies in most 3-D games are equipped with rudimentary path-finding, planning, and randomized behavior, but it’s nothing like what an AI does for Chess. These mainstream AIs are essentially trying to mimic believable human behavior, not provide an opponent with which you can explore the depths of the game mechanics.

The discussion of AI adds a final wrinkle to include in this article’s fundamental question, which I will now pose explicitly here:

Can you make an AI-free, randomness-free, physical-challenge-free, single-player game with gameplay depth akin to that of Go?

Is there any hope for the single player art game that seeks to provide that kind of depth at the gameplay level?

I now firmly believe that the answer is “no.” The proof comes from considering how one might go about winning, or doing well at, such a game. If there is a single, optimal path to victory, then systematically finding that path is the main task in the game. Once the path has been discovered and documented for future use, the game’s depth is exhausted. If there are multiple possible paths to victory, finding the rest after you’ve found one is an optional act of completionism, an exploration of mechanical depth.

So that’s my answer to that question. But my answer to that question didn’t stop me from trying to make such a single-player game anyway.

I’ve tried to create the deepest possible single-player, abstract strategy game that I could. I went with a score for a success metric, because a binary win/loss condition felt too much like a straight puzzle.

The main thing that I noticed during the design process was how incredibly hard it was to wring even the tiniest bit of depth out of any single-player mechanics. I tried out many possible mechanical systems, but most revealed degenerate cases that led to infinite scores or trivial strategies that led to nearly optimal scores. Even after ironing out these problems, it was often easy for me to find a strategy for doing well at the game and then be unable to improve upon that strategy through modification. Adding more layers of mechanics didn’t ever seem to help the gameplay. In the end, after finally discovering a mechanic that had some depth to it, removing almost all of the other mechanics made room for that one interesting mechanic blossom to its fullest potential.

This felt like a sharp contrast to my experience designing two-player games, where it seemed that I could pretty much slap down any old mechanics and see quite a bit of depth emerge. Go’s extreme mechanical simplicity may seem like a special case, but deep, simple, multiplayer mechanics are more the rule than the exception. For example, using Go equipment, there are even simpler games that offer similar depth, like Gomoku and Hex.

During the design process, I was aware that almost any of the failed single-player mechanics I was exploring would have instantly leaped to life in a two-player environment. The degenerate, trivial-high-score strategies would melt away as the opposing player found simple counters for those strategies.

The resulting game, which I’ve called i45hg (a nonsense name, so don’t read anything into it), is reasonably interesting, at least for a few plays. Still, the play experience is much more akin to chipping away at an optimization problem than playing a real game. Once you discover a reasonable heuristic, you will likely lose interest quickly. Oh, and as a reference point, my high score, so far, is 84.

The Rules of i45hg

During each turn, you must place nine white stones on vacant blue squares. After placing the stones, and possibly retracting and replacing white stones lingering from previous turns, clicking the green arrow will commit your moves. During the commit process, various transformations take place and points are tallied. You then you move on to your next turn, placing nine more white stones. The following three rules govern the commit phase:

1. A white stone that is adjacent to one or more black stones scores a point.

2. A white stone that has less than three white neighbors becomes black.

4. A square that has three or four black neighbors is removed from the game (replaced with a blank, unusable square).

The game gives you hints about the effect of your move before you commit. For example, white stones that will become black, due to rule 2, are marked with gray.

Squares that will be removed, due to rule 3, are marked as ghosted blank squares. In the following picture, the empty square near the middle is adjacent to three white stones that will become black when the move is committed.

Note that ghosted blank squares do not block the placement of white stones during your turn.

White stones that will score points are marked with orange. The following picture shows all the hints in conjunction. Eight of the white stones will become black, so they are marked with gray. Six of the white stones, including four that are marked with gray, have black neighbors, so this turn will score six points when it is committed. Four squares will have three or more black neighbors after this turn, so they will be removed.(Source:escapistmagazine)

闽公网安备35020302001549号

闽公网安备35020302001549号