动态定价时代释放鲸鱼玩家消费潜力

作者:Nicholas Lovell

你的游戏价值几何?开发商和发行商经常忽略这个问题。他们认为所定的价格很合适(游戏邦注:实体商店中盒装游戏一般售价为30至40英镑),就不费神去考虑价格的问题了。

但是事实上,这个问题的答案就是“用户愿意花多少钱”。

长久以来,游戏行业的运营都处在神话之中。支撑其运营的神话是,用户愿意为游戏花多少钱由行业说了算。

但事实并非如此。

我可以想到4种让用户改变游戏价格的方法:

购买二手游戏;等待价格在数月后下落;从好友处借游戏;盗版。

事实上,零售商对游戏价格的影响力比发行商更强,所以第5种方法是从Sainsbury等地方购买游戏,而不是GAME或其他独立零售商。

现在我们已经破解了游戏发行商控制用户为游戏花多少钱的神话,稍停片刻考虑下为何发行商从一开始便会设定单一价格或许有一定价值。

出售实体商品很困难

在互联网还未普及的年代里,商品出售只有一个途径:实体店。

出售实体化的商品非常困难。你需要准备生产、包装和储存。你必须投入资金生产出数十万套产品,努力将其销售出去,只有这样你才能知道这种产品能够售出还是只能埋在内华达州的沙漠中。

而且,还需要支付主机生产商的版税和营销游戏的费用。

毫无疑问,游戏的成本会很高。

(游戏邦注:这里所说的不是开发成本。《使命召唤:现代战争2》的开发成本为5000万美元,生产和营销费用为1.5亿美元。对于多数游戏而言,开发成本在总成本中所占比例很小。)

在我们继续深入探讨之前,我想应该先说说价格和需求曲线。

价格和需求曲线

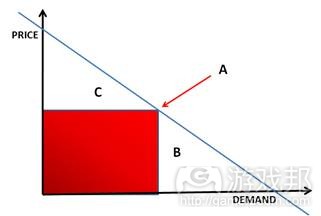

下图可能是最为简单的图例。图表中显示的价格和需求曲线是条直线,表示随着价格下降,需求量会逐渐上升。如果你将商品的价格设置在A点(游戏邦注:红色箭头所示),那么你就能够从阴影区域内的所有用户中获取到最大化的价值。

区域B中的用户是你失去的用户。他们不准备花A美元来购买产品。他们更愿意放弃这个产品,而不会付全额购买。

区域C中的用户对产品的这个价格感到甚为满意。他们甚至愿意支付更多的金钱来购买产品,但是价格是固定的。营销人员将商品价格设定为A美元,就无法赚到这些人愿意多付出的金钱。

从传统意义上来说,营销的作用是使需求曲线上的潜在购买者购买产品。使用营销技术增加他们对产品的需求欲望,直到他们开始认为产品价格是合理的。营销活动需要耗费大量的金钱,用John Wanamaker的话来说,“我花在广告上的半数资金是毫无用处的,问题在于我不知道浪费的是哪些资金。”

在实体销售的世界中,对于那些甘愿付出更多金钱的顾客,营销人员无计可施。毕竟,将区域B中的用户同区域C中的用户区分开来并非易事。即便你可以将这两个群体区分开来,也很难为他们提供不同类型的产品。

所以我们不得不接受40英镑的心理价位,被迫以等待、二手交易或购买盗版等方法,用我们认为合理的价格获得想要的产品。

动态定价时代

现在,我们进入了动态定价时代。这为那些理解如何发掘最大潜力的人提供了大量的机会。

如果你不相信,看看Turbine的做法就知道了。他们努力地使《龙与地下城Online》变得商业化。所以他们将游戏转变为免费游戏,然后通过虚拟商品来盈利。

如此做法的结果令人震惊,在最初半年内盈利增加了500%。一款处在困境中的游戏变成了一款非常成功的游戏。像我这样的评论员为此大为狂喜。这种现象支撑了我们认为玩家偏爱免费游戏的论断。根据看到的这种情况,我们说道:“看看,当你让人们慢慢在游戏中花些许金钱,减小玩家进入游戏的障碍,你就会获得更多的盈利。”

但是,我们是错误的。

错误的地方不在于结果。免费游戏的做法确实奏效。Facebook、iPhone和传统MMO游戏所取得的成功都可以说明这一点。

错误在于我们的推理。事实证明,动态定价释放的不是区域B中的消费潜力,而是区域C。

简单地说,参与其中的是鲸鱼用户,是那些愿意在游戏中花大笔金钱的粉丝。

鲸鱼用户在游戏中花费的金钱足以令人震惊。有一家主流网游公司80%的盈利(游戏邦注:以千万美元为单位衡量)仅来源于其中的2.3万个用户。

真正的事实是,免费游戏的作用不是让许多人免费玩游戏,而是允许少数玩家在他们钟爱的游戏中花上大量的金钱。虚拟货币供应商Jambool发现英国、美国和沙特阿拉伯都有此类鲸鱼玩家,他们表示世界各国都存在此类玩家。

Bigpoint声称其ARPPU(游戏邦注:每付费用户平均盈利)高于《魔兽世界》。“平均”是这个度量中的关键词。有些人只在游戏中花1到2美元,有些人会花上百美元甚至更多。

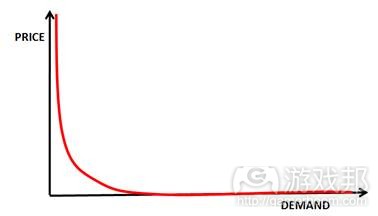

事实上,游戏的价格和需求曲线并不像我们之前讨论的那样。这条曲线属于幂次法则。

多数用户希望游戏能够免费。他们并不认为游戏很有价值,玩一段时间后就会将其遗忘。

少数用户认为你产品的价值与你设定的价格相符,比如40美元的盒装产品、10美元的订阅MMO和0.99美元的iPhone应用。

不足1%的极少数用户非常喜欢你的游戏,他们愿意在上面花上大量金钱。这便足够为你的游戏带来盈利。

可笑的是,我们这些游戏制作者已经知道了这种情况。我们已经知道了我们拥有某些十分喜爱我们的游戏的硬核玩家。他们会自行制作mod,创建自己的网站,在游戏中花上很长时间,自称是我们最忠诚的粉丝。

而我们只是让他们通过花钱来表示对我们的欣赏。

我们是在利用自己的用户吗?

当然不是。

我们应当允许并鼓励那些想要为这些内容花更多钱的用户。

这里有个条件。你必须向他们提供其真正需要并且能够增加他们生活价值的东西。我说的就是他们的生活,许多此类东西的价值已经超越游戏进入现实生活中。

在免费游戏中,你很容易就可以知道可以提供哪些内容。你可以创造出游戏内置道具,将它们以1美元、10美元或100美元的价格出售。传统游戏中的做法也会如此简单吗?

我觉得是这样的。我们可以看到需要额外购买的“特别编辑”包,玩家可以向他人吹嘘自己获得了夜视护目镜。我们也可以看到有着极高售价的可下载内容。事实上,这些内容甚至高到让我认为原版游戏并未含有完整的设计,其目标只是吸引玩家并从中找出鲸鱼用户,然后通过扩展包、游戏内置道具和其他可下载内容从这些人当中获取盈利。

简而言之,免费增值模式出现在所有类型的游戏中。

原因很简单:发生这种事情是因为玩家的需要,也可以帮助公司对游戏进行商业化运作。

我觉得,如果你在制作游戏的话,你需要理解互联网不仅改变了我们销售游戏的方式,还改变了玩家的期待。我们即将进入动态定价、满足鲸鱼用户、让多数用户免费享受大部分游戏内容的时代。(本文为游戏邦/gamerboom.com编译,如需转载请联系:游戏邦)

HOW MUCH IS YOUR GAME WORTH?

Nicholas Lovell

How much is your game worth? It’s a question that developers and publishers don’t ask often enough. They think that the price is pretty well set (around about £30-£40 in the shop) and don’t bother thinking about pricing very hard.

But the truth is that the answer is this: “Whatever your customer chooses to pay”.

The games industry has long operated under a myth. It operates under the myth that the industry determines what price a consumer pays for a game.

This is not true.

Off the top my head, I can think of four ways that consumers can alter the price of a game: by buying a used game; by waiting a few months for the price to drop; by borrowing it from a friend; by pirating it.

In fact, retailers have a stronger influence over the price than publishers, so a fifth way would be to shop around and buy your game from Sainsbury’s rather than GAME or an independent retailer.

Now that we’ve dismissed the myth that games publishers have control over the price consumers pay for games, maybe it’s worth stopping for a moment and thinking why publishers set a single price point in the first place.

Selling physical stuff is hard

In the pre-Internet days, there was only one way of selling content; physically.

Selling stuff physically is difficult. Very difficult. You have to arrange for manufacturing, packaging and warehousing. You have to invest in hundreds of thousands of units, store them, distribute them and only then do you get to see if they sell or if you will be burying them by the truckload in the Nevada desert.

And that’s not including the royalties due to the console manufacturers or the cost of marketing the game.

No wonder a game cost so much.

(Note: it’s not about dev costs. Modern Warfare 2 cost $50 million to develop and $150 million to manufacture, market and distribute. For most games, development costs are a fraction of the total costs.)

Before we go any further, I think it’s time to talk about the price/demand curve.

The price/demand curve

This is the simplest illustration possible. The price/demand curve shown here – in fact a straight line – shows that as the price falls, the demand rises. If you set the price of a good at point A (indicated by the red arrow), then you will capture the maximum amount of value for all consumers who fall into the shaded area.

Customers who fall into area B are lost customers. They are not prepared to buy the product for $A. They would rather forgo the product than pay a full price for it.

Consumers who fall into area C will be delighted by the price. They would happily have paid more for this product, perhaps much more, but there was no mechanism to let them. By setting the price at $A, the marketer has left that money on the table.

The role of marketing, in a traditional sense, has been to shift potential purchasers up the demand curve: to use marketing techniques to increase their desire for the product to the level that they will start to view the price point as reasonable. This can be expensive, especially since, in the words of John Wanamaker, “Half the money I spend on advertising is wasted; the trouble is I don’t know which half.”

In the old world of physical distribution, there was nothing marketers could do about people who would happily have paid much more. After all, there was no easy way to separate customers who fall into group B from customers who fall into group C. Even if you could separate the groups, it was hard to offer them differentiated products.

So we were stuck with £40 RRPs and were forced to wait, trade-in or pirate to get titles we wanted at prices we thought were reasonable.

Welcome to the era of dynamic pricing

We have now entered the era of dynamic pricing. It offers huge opportunities to those who understand how best to make it work.

Don’t believe me? Ask Turbine. They were struggling to make Dungeons and Dragons: Online work commercially. So they took a deep breath and turned it into a free-to-play game, monetised by virtual goods.

The result was staggering: revenues were up 500% in the first six months. A struggling game became a very successful game. Commentators like me were ecstatic. It vindicated our arguments in favour of free. “See,” we said, “when you let people spend a dollar here, five dollars there, reducing the barriers to entry, you get much more money.”

Boy, were we wrong.

Not about the results. Free-to-play is clearly working. It works on Facebook (see Zynga). It works on iPhone (see ngMoco). It works for traditional MMOs (see Dungeons & Dragons: Online and The Lord of the Rings Online).

We were wrong about the reasoning. It turns out that dynamic pricing isn’t about releasing the potential of the cheapskates in the area labelled B under the price/demand curve; it’s about the area labelled C.

In short, it’s about the “whales” – the high-spenders – the fans who want to spend a lot of money on their title. It’s not about the tiddlers.

The concentration of spend amongst the whales can be staggering. One major online games company sees 80% of its revenue (which measures in the tens of millions of dollars) from just 23,000 users.

The real truth about free-to-play games is not that they allow many players to play for free; it’s that it allows a few players to spend huge sums of money on their favourite game. Jambool, a virtual currency provider, has identified high-spenders in the UK ($11,635), the US ($19,054) and Saudi Arabia ($25,540) and says that similar high spenders can be found right around the world.

Bigpoint has said that its Average Revenue per Paying User (ARPPU) is higher than that for World of Warcraft. The key to that statement is the word “average”. Some people are spending a dollar or two; others are spending $100 or more.

In truth, the price-demand curve for games looks nothing like the curve we discussed earlier. It’s a power-law.

Most of your users want your game for free. They don’t value it very highly, will play for a bit, and then forget about it.

A few of your users value your product at exactly the price you would normally set it at. $40 for a boxed product. $10 for a subscription MMO. $0.99 for an iPhone app.

A very few, a small fraction of one percent, love your game so much that they want to spend lots of money on it. Enough to make your game extremely profitable.

The ridiculous thing is that we, as game makers, already knew this. We already knew that we had hard-core fans who loved our games to bits. They would code their own mods, create their own websites, commit hours to gameplay and claim to be our biggest fans.

We just didn’t give them any way to show that appreciation though spending money.

Are we exploiting our customers?

Emphatically not.

Customers who want to pay more for the content they consume should be allowed and encouraged to.

There is a proviso. You have to offer them stuff that they really want and that adds value to their lives. (I do mean their lives; much of the value of this stuff goes beyond the game and into real life, but I haven’t got time to cover that here.)

In free-to-play games, it’s easy to see what you can offer. You can create in-game items and offer them for a dollar, ten dollars, a hundred dollars. Is it so easy in traditional games?

I think so. We are seeing premium “special edition” packs which come with bragging rights “I’ve got the night vision goggles”. We’re seeing downloadable content with very high tie ratios. So high, in fact, that I can envisage a time when the original game is a loss-leader designed to draw gamers in, to identify the whales and to monetize them through expansion packs, in-game items and other DLC.

In short, a variant of the freemium model is coming to every type of game.

The reason is clear: it’s happening because it is what gamers want (as evidenced by their wallets); it’s happening because it’s what makes sense for companies on a commercial level.

I believe that if you make games, you need to understand how the Internet has not just changed how we distribute games. It has changed the expectations of gamers. It has ushered in the era of dynamic pricing, of satisfying the whales and of making much of your content available for free to most of your users.

As a businessman, as a gamer, as someone who helps companies make games, I couldn’t be more excited. (Source: Games Brief)

闽公网安备35020302001549号

闽公网安备35020302001549号