万字长文,从机制设计角度激活玩家的游戏创造性

作者:Eddy Léja-Six

如何将创造力引入游戏中—-可能吗?设计师Eddy Léja-Six通过解释创造力和游戏的本质,提出的最终问题是:什么样的游戏允许创造力以及这类游戏如何鼓励创造力?

创造力和游戏是人类活动中最重要的两个方面。儿童花大量的时间用于游戏和发明,并且通常是同时:“现在你是抢银行的劫匪,我会骑一只看不见的恐龙来追捕你!”

许多成年人会告诉你,他们不玩扫雷是因为它“简直算不上游戏。”其他人会说是因为那些人不够创意,他们“不懂怎么扫。”

事实上,创造和游戏正是人类生活的组成部分,就像呼吸一样自然而然,基本上也是很益的。

作为电子游戏开发者,我们都知道如何娱乐玩家,给他们提供有意义而触动的体验。但我们拥有让玩家在游戏时产生创造力的必要工具吗?游戏如何激发玩家的创造力?我们应该 试试将玩法与创造力相结合吗?

首先,什么是创造力?以下定义是我认为最多人会赞同的:

创造力一种让我们找到和运用新想法的心理过程。

我将在下文中继续充实上述定义。

calvin_hobbes(from gamasutra)

摘要

本文的目的在于剖析电子游戏中的玩法是否能够以及如何与创造力相结合。我会尽量引用相关的游戏作为案例。在我达到最终目的以前,我要先完成以下任务:

1、充实创造力的含义

2、定义游戏玩法

3、鉴定现存的游戏如何将二者相结合

4、分析试图给予玩家创造自由的游戏为什么会成功或失败

用户生成内容

在电子游戏中,关于创造力的最明显的例子当属用户生成内容。关卡编辑器和角色自定义存在已久,而最近的游戏如Media Molecule的《LittleBigPlanet》给予玩家的创造机会更 是多得令人惊叹。

我们来看看用户生成内容和可以将其视为创意玩法的标准。

试玩《Faceez》

在Neko Entertainment公司,我们开发了一款DSiWare应用,名为《Faceez》。在这款游戏中,玩家可以混合、装饰和动画照片中的人脸。这是我参与制作过的唯一“非游戏”的应 用,它向玩家提出的创造力要求比我设计过的所有游戏都高。事实上,整个应用就是一个角色自定义菜单。

当然,一款应用和一款游戏之间的区别在于玩法。所以,就玩法能不能与创造力相结合这个论题,《Faceez》绝对算不上一个好例子。但它告诉我许多关于玩家如何在软件中产生 创意的线索。

faceez(from gamasutra)

(如果有人要拿你的脸来装饰你设计的软件,相信我,你应该拒绝。)

试玩《Faceez》非常有趣,产生了两个不同的现象:玩家根据经验浏览游戏资源(附件和动画)中的可用选项,然后使用随机按钮,最后才开始自己设计。相反地,当从他们自己 拍的照片中混合脸蛋时,玩家马上就产生创意想法了。这是什么呢?

玩家使用的照片是他们周围的人的。使用游戏资源和自己拍的照片的区别是,玩家已经认识照片中的人物了。一旦他们知道系统如何运作,他们立刻就想到如何使用自己拍的照片 :

“我姐姐长着我的粗眉毛……”

“我留着老板的发型!”

“喔,我可以布拉德皮特的照片跟我的混合起来!”

“等等,将我、布拉德和我邻居的照片跟猩猩组合在一起会怎么样呢?”

……

完成这些构想可能需要测试、验证、修改想法和机遇……但在这个过程中,始终是有想法的——有创意的想法。

相反地,在玩家产生创意想法以前,在《Faceez》中做一只挥着刀虚张声势的金枪鱼,他必须:

根据经验,知道应用包含一个金枪鱼的附件和一段挥刀的动画。

或猜想这两个选项必须可用——我的意思是,只有蹩脚的游戏才会没有金枪鱼!然后是主动搜索选项。软件用户极少那样想,因为结果通常是令人失望的。当然,猜想也是一种不 错的体验(我们后面再谈)。

要有创造力,玩家必须很清楚存在什么可用选项。

这一点的负作用是,玩家的选择越多,学习和掌握所需的时间就越长。是吧?

叫什么名字?有什么任务?最喜欢的颜色?

想象一下Xbox 360中的Rare的角色编辑器如果只有四种发型、三种鼻形、两种衬衫……会怎么样呢?在这种条件下玩家会产生创意吗?玩家可以混合这些元素得到他想要的结果吗 ?或者玩家就喜欢最合适的搭配?

创造力只有在选择多时才可能发生。

看来有矛盾了:要产生创意,玩家必须很容易地就理解游戏给予他们的选择。但为了容易,我们又不得不减少需要学习的选项。但这么做又减少了可用选项,进而减少了创造的可 能性。

Five_minutes_to_kill_yourself_copy(from gamasutra)

(Adult Swim的《Five Minutes to Kill Yourself》的角色自定义设计得相当好,因此创造力完全是不可能的;通过大量减少有意义结果的数量,它很好地贴合了游戏世界的消极 气氛。)

在《The Art of Game Design》中,Jesse Schell分享了一段关于间接控制的有趣经历:

在游乐园时,我有时会在糖果店打工。我就站在60种口味的棒棒糖前面,每天都听到有人问:“你们有什么口味的?”

一开始,我自作聪明地背诵60种棒棒糖的口味——当我这么做时,顾客会目瞪口呆地在我背到第32种口味时叫停:“好了!好了!够了!”他们完全被这么多的选择搞晕了。过了 一阵子,我想到了新的回答。当顾客问口味时,我会说:“只要你想得到的我们都有。好吧,你最喜欢的是什么口味——我肯定我们有。”

他们先是很惊讶居然有这么多选择。但之后他们就皱眉了,想得很辛苦才说:“呃……樱桃?不要,等下……嗯……薄荷?不……算了。”说罢,他们郁闷地走开了。

最后我想出一条策略,帮我卖了很多棒棒糖。当有人问口味时,我就说:“只要你想得到的我们都有,但最受欢迎的口味是樱桃、蓝莓、柠檬、沙士、冬青和甘草。”他们会很高 兴有这么多选择,但更高兴的是有几个中意的选择;事实上,大多数顾客都会从“最受欢迎的六种”中选择,而这六种我会经常改的,好让其他口味的棒棒糖不会在货架上留太久 。

间接控制可以避免玩家对过多的创意自由感到不知所措。其实,默认配置和“随机”按钮的作用就在于此。它们告诉玩家:“你可以随意设计你的角色,或者使用默认的这个。”

为什么要在口红和胡子之间做选择?

这个问题的另一个经典解决方案是,减少选项的数量,但允许玩家组合选项,这样就仍然可以产生许多有意义的结果。例如,玩家在《魔兽争霸3》(暴雪)有12种颜色可选择;因 此有12种可能的结果。而在《泰坦之旅》(Iron Lore)中,玩家的性别选择有2种,服装选择有5种。

我们可以通过计算各个选项的结果比率来评估系统的组合深度:在《魔兽争霸3》中,玩家有12种选项和12种可能的结果。12/12=1,所以它的比率只有1。完全没有组合深度。《泰 坦之旅》共有7种选项(男性、女性、白、褐、蓝、灰和红)和7种可能的结果。这意味着它的比率是10/7=1.42。

组合选项的能力对需掌握选项的数量和有意义结果的数量影响很大。它满足了某些游戏的要求:挑选一种几乎算不上自定义的颜色:暴雪的设计师需要不同的颜色让玩家看起来不 一样,所以《魔兽争霸3》就有了12种角色。而在《泰坦之旅》中,增加了男性和女性的性别选择,这是自定义组合的初始阶段(游戏的后期,角色的外观也会因为装备和增益魔法 而有所区别)。

注: 我一直强调“有意义”的结果是因为,如果变化太过细微,根本不能产生可以感知的区别,那种结果就是“无意义”的;比如,将角色的下巴移动1毫米,这种变化等于没有 变化。

Little Big Planet(from gamasutra)

(就自定义和创意方面而言,《LittleBigPlanet》可能是最有深度的游戏。)

组合选项的方法表明,游戏玩家只能通过组合已经存在的物品来产生创意。除此之外,创造力是非常有限的。但是,组合旧东西不能算作一种有创意的过程吗?正如斯坦福大学的 Robert I. Sutton所说的:

创造力是利用旧东西做出新事物。

一个想法要被称作创意,必须是全新的吗?好吧,创新只是一种心理过程。如果玩家认为他们发明了世界上从来不存在过的东西,那就是创新。所以,创新只需要对创造者来说是 新的就行了——而不是对世界上的其他人来说。

但正如我所说的,《Faceez》没有玩法。其他非常有创意的游戏,如《Elektroplankton》(Indies Zero)或《Art Academy》(Headstrong),也没有什么玩法。为了发现用户生 成内容如何成为玩法的一部分,我们必须先定义一下“玩法”是什么。

什么是“玩法”?

读者们应该都很明白什么是电子游戏,所以我就不再多说了,也不打算在这里重新定义它。注意:本文包含的观点可能会让某些读者不能认同。如果你认为《The Sims》不是游戏 ,那么你不要再往下看了。

我们都知道游戏可以做得“有创意”,就像杂志也可以做成拼贴画。我们必须确认,在游戏过程中,是否可以发生创造力。令人吃惊的是,“玩法”这个词并没有得到一致的定义 。Tom Heaton认为:“大多数人都会同意这条宽泛的定义‘游戏的元素’。但不同意的人很快就会提出游戏玩法到底是什么,它的元素是什么,为什么一种特征能促进玩法而另一 种不能。”

出于本文的目的,我将提出一条我个人的定义。玩法是游戏流的核心。因此,玩法是玩游戏这一活动的中心。

电子游戏的玩法活动的例子有:探索地图以发现隐藏的秘密、移动白色方块后弹出一个白色的方块、在《Track D》上用42号车创造个人时间纪录、装备新防御物品以增加武器等级 、或爬上高山看看你能眺望多远。等等。

那么,什么不是玩法?例如:浏览菜单来选择游戏模式、看过场动画、调节音量或在游戏大厅等待匹配玩家。

玩法产生时,玩家应该:

-有目标

-在实现目标的过程中存在阻碍而不能立即达到

-必须采取行动来克服这些阻碍

当然,不同游戏的细节可能相差很大:可能是同时有几个目标,可能玩家要自己选择或创造自己的目标,阻碍可能是由任务、规则、迷宫、谜题等组成的,需采取的行动可能需要 玩家动脑筋(“要不要现在就升级我的基地呢?”)或纯粹的条件反射(“用特殊技能吧!”)

玩家生成内容对玩法的影响

游戏越来越多地允许玩家创造他们自己的角色、关卡和游戏世界。可用选项的数量和深度决定了玩家的自由程度。在大多数编辑器中,可能结果的数量多得令人眼花。

这些编辑器中有许多是与玩法无关的:例如,制作关卡并分享,让玩家成为关卡设计师。你大概知道,关卡设计本身并不是游戏。

有时候,玩法可能会影响这些编辑器,最常见的就是通过解锁选项和道具(“干得好!你升到2级啦!你可以用3×2平台制作新关卡了!”)但是,即使在这种情况下玩法打开了创 造力的大门,它也没有使创造力成为玩法的一部分。当扑克玩家花掉她羸来的钱时,她扮演的就不再是扑克玩家的角色。

有时候,玩法也可能限制创造力。例如,在Lionhead的游戏《The Movies》中,玩家管理一家电影制作工作室,编辑电影的工具很多,但只能让可用演员出演,或使用已经解锁的 场景等。再者,在一部电影中能使用的创意方法并不会影响玩法。创意的结果只是,在线分享一段非常不错的视频。

《Audiosurf《(Audiosurf LLC)和《Vib-Ripple》(Nana On-Sha)等游戏用音乐或照片作为关卡设计的材料。即使有创造性的资源,它们通常也是在游戏之外制作的(大多数时 候不是玩家做的。Prodigy是我最喜欢的《Audiosurf》关卡设计团队。)

APB_copy_2(from gamasutra)

(《All Points Bulletin》(Realtime Worlds)允许玩家将自己的持枪角色变成70年代的蓝胡子色情影星。)

最普遍的自定义功能允许玩家改变角色的外观。这种编辑通常很多,但对游戏玩法没有影响:例如,我曾经给Commander Shepard(BioWare的《质量效应》中的角色)的脸上加上 小胡子,但显然,这不会影响人们对他的反应。

当然,玩法不是游戏的一切。角色的外观对游戏体验是有影响的;否则大游戏工作室也不会那么麻烦地开发那么多自定义功能了。玩一个自定义出来的独特角色会改变玩家对整个 游戏的印象……可能会让玩家意识不到自己只是在操作第65535个玩家角色。在线分享创意也让玩家非常有满足感。但毫无疑问,这种创造虽然很有益,但它与游戏玩法并不直接相 关。

我可以让加农炮换一种颜色吗?

然而,角色编辑器也可能对玩法有影响。在Bethesda Softworks的《天际》中,玩家可以从10种角色中挑选1种。玩家的选择会影响角色的属性、技能和某些NPC对角色的反应;还 决定了其他自定义选项是否可用。例如,Khajiits是长得像猫的种族,玩家可以给它定义很多种面部特征,但角色始终是像猫。

在这个例子中,我们看到玩家的选择有10个与玩法相关的结果,以及上亿种纯外观的结果。通常在角色自定义选项中,与玩法相关的选项(如技能、种族、特技)比外观选项少( 颜色、服装、面部特征)。

为什么会这样?好吧,所有做出好系统的设计师都知道,不同元素越多,越难实现平衡。在开发后期增加一两种新技能可能会毁掉整个玩家体验,而在发布前一周增加15种胡子形 状却很安全。

除非我们说的是《Fable》(Lionhead),在这款游戏中,面部毛发可是有非常重大的意义。记着:Sheriff的胡子会让你非常迷人,但也很可怕!

现在看来,玩法自定义几乎没给玩家什么创造的自由:没有大量选项,创造力就是不可能的。提供大量游戏玩法相关的选项相当困难。当然,并非没有例外。

Maxis的《Spore Creature Creator》可能是有史以前最有深度的角色创造工具。它允许玩家产生亿万种完全不同的生物。不用说,任何允许创造七条腿、三个鼻子的生物的都是令 人惊艳的创意工具。另外,已选中的元素会影响生物的能力:它靠翅膀飞,大尖牙说明它食肉,灵活的脚让它跑得飞快。

其他几款游戏允许角色自定义也对玩法也有影响,如《Impossible Creatures》(Relic)和《Freakyforms 》(Asobism)。当使用这些编辑器时,角色的原创性和能力就有冲突 了。有时候,这种冲突会导致甚至更多的创意,但也可能是令人失望和不符逻辑的结果:想象一下,你要创造一个完美的捕食者,它有许多尖锐的爪子。之后你查看它的属性发现 ,因为你使用的是基础等级1的爪子,所以它的攻击力非常弱……

跟朋友说到这一点以后,我发现他也有同样的疑问,抱有和我相同的想法(创意)。他在生物的脚之间添加了一个攻击等级5(最大值)的小东西,没人会看到。就这样,这个生物 具有了他期望中的战斗力;但它并没有毁掉他想要的外观,除了多了一条锋利的小东西。

Spore(from gamasutra)

( 左边的生物有1级的攻击选项(打、咬和冲),而右边的有相同的攻击动作,但等级是5。在近身战中,这只单腿的青色小怪物真的比紫色的大块头强五倍么?)

相同的现象(自定义与玩法之间的互补或相克)也出现在其他游戏中。《SimCity》(Maxis)的玩家可能会发现,他们想建设的小镇完全行不通。这种发现可能是一种有趣的体验 (“啊,人们不会交两倍的税来建这么奢华的公园!”)但即使是这样,执行这种创意确实减少了玩法的效率。玩家意识到自己的两个目的并不能兼顾:一是创造一个“我自己” 的小镇,二是避免破产。

相反地,之后玩家更加理解游戏的玩法,想出有创意又高效的设计。《Spore》的玩家也一样。玩家在这款游戏中制作的生物往往与游戏的逻辑一致,同时又具有突出的创意,即使 那些玩家并不知道游戏是如何运作的。

知道游戏规则和游戏世界的逻辑的玩家不太可能犯下可笑的错误——如给一个隐密的角色戴上三副亮绿色的眼镜。

创造力的语法

一个众所周知的真相是,这个世界上最伟大的发现往往来源于转瞬即逝的灵感。当然,首先得有大量的基础工作,但对整个发现起决定作用的是,比如一颗下落的苹果或一只沸腾 的水壶或溢出澡盆的水,这些东西启发了观察者,让他们犹如醍醐灌顶。据说,发现DNA的形状要归功于科学家苦思冥想之际偶然看到螺旋形的楼梯。如果他是搭电梯,整个基因科 学的发展恐怕要被推迟了。

- Terry Pratchett,《Sourcery》

美学和玩法丰富的设计之间的根本区别是什么?事实上,它们使用的不是同一种语言。当玩家根据玩法(使用所有满足某种操作风格的必要技能)制作《Spore》中的生物时,他们 考虑游戏的规则、可能遇到的障碍、最终目标和达到目标的方法。

那么,在玩家很了解玩法以前,他们设计创意的动机是什么?确实,当他们在《Spore》中制作第一个生物时,他们并不清楚自己将面临什么问题。是的,他们的感觉是不是就像脑 袋空空时使用Zbrush雕刻东西?当然不是。

对于初级玩家,使用编辑器是很容易的,因为游戏会指导你,你不会遇到“脑袋一片空白”的情况。但主要的区别可能是,玩家知道他们的生物会生气勃勃(即使他们不知道它是 否能生存很久)。当设计他们的生物时,玩家根据他们想象中的游戏世界的样子来想象它将如何过活。

如果创造力是指组合旧想法以产生新想法的能力,那么我的问题是:这些旧想法从哪里来?大多数玩法相关的自定义系统是非常狭隘有限的,并没有给玩家太多选项来实现创意。 来自其他领域的想法通常没有太多价值。唯一相关的语法是严格内源性的。

当编辑工具有足够的深度,允许玩家根据创意来设计时,如在《Spore》中,玩家使用的语法就广泛得多了。可能是组合了来自现实世界的(“看看我的蝴蝶飞花!”)、游戏世界 的(“其他生物都想吃的小飞物”)、日常生活(“模仿我那位恶心的数学老师”)、想象(“一个大阴茎”)、文化符号(“长了狼人爪子的辛普森”)或同时来自许多不同的 语法(“长着大阴茎、中间带滑轮的、飞翔的辛普森”)

butterfloctopus_copy(from gamasutra)

(这正是为什么《Faceez》的照片能让玩家产生创意。游戏不仅给予玩家大量选项,而且允许使用玩家已经知道的语法。)

当然,创造一些同时满足创意语法和玩法语法的东西总是有可能的。有时候,效率也具有自身的美学价值,熟悉游戏的人仅通过观察(“我看到你已经设计了一只群居动物,让它 变成短跑能手是个好主意,以防万一嘛!”),就能够解码创意的特征。

无论想法来自哪里,将不同来源的概念联系起来的能力正是创造力的基石。或者更简单地说:

创造力需要灵感。

灵感主要是指大脑联系已存在的想法,以形成新的样式、概念、活动……这个过程大部分是无意识的,而且来无影去无踪,虽然如此,但总有激发灵感的办法。

我们已经探讨过随机按钮如何使玩家熟悉可用的选项。随机性可能也会带来创意,就像浏览自己搜索到的图片或在头脑风暴大会时听其他人发言。随意流动的概念是思考的养料。

随意性条件可能发挥着相同的作用:当你唯一拥有的工具就是一把锤子时,任何席琳狄翁的CD都可能带给你灵感。条件不仅给玩家提供创造的元素,但也意味着一定数量的限制。 有时候限制会引导灵感;有时候又会摧毁灵感。玩法的语法限制了自定义的过程。这些限制可能促进新创意的诞生,也可能抑制并扼杀所有创意的思维。结果是,用户生成内容虽然鼓励灵感和创造力,便并没有让它们成为玩法的一部分。几乎没有游戏允许创造力对玩法产生重大影响,无论前者起的增益作用还是冲突作用。

冲突来自不可避免的事实:所有玩家至少有一个玩法目标。用户生成内容可能或可能不会与这个目标结合得很好。这就提出了一个重要的问题:创造的目的是什么?

缪斯女神的秘密

对于我们所有人,创造力会唤起观察、联想和想象。这确实是创造力的一个非常重要的方面:没有想象的能力,创造力就不存在了。

但创造力还不止于此。它是有目的的。这个目的可能是变化的,无意识的,随意的,愚蠢的……但仍然是一个目的。如果你没有目的,那你就不可能有创意。创造是灵感加上汗水 。

从理论上说,抱有一个目标和提出一个问题是同一件事。当然,它们听起来是完全不一样的。例如,我可能指责你自己给自己制造问题,但我会表扬你定下了自己的目标。哪个听 起来更好?虽然感觉不同,但我说的确实是同一个情况:创造你自己的问题就是给你自己树立目标。类似地,树立了你自己的目标,你也就面临着如何达到它的问题。

创造力是一种解决问题的能力;它需要目的。

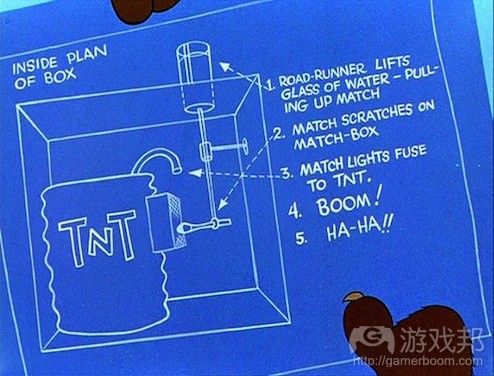

coyote(from gamasutra)

(ACME 统计学表明,土狼挨饿时的创造力会比平时高78%。)

生活充满了目标:野心、梦想、必须品、职业挑战和要求、社会义务……所以哪一种现实的问题有办法通过“找到并运用新想法”而得到解决呢?很多:结束商业合同、让你的孩 子吃蔬菜、想一个笑话打破沉寂、把所有行李塞进车里、周日晚上写一篇10页的作文、打开荒岛上的宝箱等。

如果说有一个目的,和找到了问题的解决办法是一样的,那么玩法和创造力就非常接近了。另外,以上例子都非常有难度。是的,它们是不是差不多?

所有游戏都至少有一个目标,没有也要玩家创造一个。否则,这个游戏就不是游戏了。但是,解决现实问题不同于解决玩法问题。在游戏中,玩家的选项有限,且不断根据游戏作 判断。

你可能会说这取决于游戏,但现实生活却不是。记住,我们在这里是将游戏比成现实生活:在与现实生活作比时,甚至模拟最出色的AAA游戏也不过包含极其简单和有限的物品和系 统。

如果说游戏的目标就是创造力,那会怎么样呢?我们来看看《Create》(EA Bright Light)是怎么说的。

因为创意而创意

《Create》是一款混合了复杂的谜题、巧妙的挑战和高度自定义的环境的游戏。虽然它是一款很好的益智游戏,且包含上百个不同的自定义选项和可解锁的玩法道具,它还是没有 达到EA网站上显示的目标:“Create tracks your creativity and rewards you for it(创造你的创意轨道,并以此奖励你自己)。”

游戏有一种特殊的挑战名为“创造链”:玩家在特定的等级时使用一套特定的工具就会得到奖励。显然 ,“创造链”的目的是给玩家很多创意的机会,以便他们了解更好的可用选 项。这些选项就好比关卡编辑器,但它们完全是内置的,且使用了相同的界面作为解决问题的玩法——就像出自《Trackmania》系列(Nadeo)的游戏,给玩家一个关卡编辑器界面 来设计他们想到的最有效的轨道。

事实上,创造不是“创造链”的真实目标。真正的目标是“使用各种工具”。玩家可能会因为使用任何一种工具和随机点击画面而得到奖励:任务是完成了,但没有产生创造力。 因为这个任务没有障碍。

玩家为了继续玩下去,只是简单地满足游戏的要求。

Create(from gamasutra)

(在上面的图片中,你可以看到《Create》给你的场景,作为“创造链”第一关的起点:主题公园。另外两张图片显示了不同的“解决方案”,同样完成系统的要求,但显然创意 程度是不同的。)

我们已经知道灵感是不能强求的。所以我们理解了为什么游戏不能要求玩家马上产生创意(“有点创意!就是现在!”)。

你不能强求创造力。

即使玩家乐意做点有创意的事,他们可能也不能马上实现。需要时间。但如果我们承认某个玩家有创意,那又怎么样呢?

如果创造力>0.5,那就继续到10

《Create》称不上是有创造力的。现在还没有游戏称得上。甚至我们有时候也很难评估其他人的想法——作为开发者,你可能理解这个难题。一个基础的游戏AI怎能解决这么主观 的问题呢?

不然,游戏通常假装理解玩家的感觉,比如,当判断玩家的内部设计(如任天堂的《Animal Crossing》)或当对你刚刚输入的名字作出反应时:“‘胡说’?天啦,真是个好名字 !”

Duke_Nukem_Forever_copy(from gamasutra)

( 在《Duke Nukem Forever》(3D Realms)的第一关,AI控制的地球防卫军战士好像接受了我写在白板上的狡猾计划。 )

任天堂的《Wii Music》有非常有趣的办法。它允许玩家挑选乐器,演奏选中的音乐,设计封面,甚至系统还要求玩家自己评估自己的作品,没有什么限制。设计师知道游戏不能判 断音乐的质量,所以唯一的态度就是玩家自己的态度。

电脑无法识别或评估创造力。

如果创造力不能被电脑识别,电脑就无法奖励它。更重要的是,它永远不会因为玩家没创意而惩罚玩家。甚至因此阻碍玩家继续游戏也是一种轻微的惩罚。

我们现在已经充实了创造力的定义。下来我们来总结一下创造力的定义:

创造力是一个让我们找到并运用新想法的心理过程。

要有创造力,玩家必须很清楚有哪些可用选项。

如果没有大量的选择,创意可能不会发生。

创造力是利用旧东西制作新东西。

创造力需要灵感。

创造力是解决问题的能力;它需要目的。

你不能强求创造力。

电脑不能识别或评估创造力。

富有创造性的解决方法

尽管在某些谜题解决关卡中,创造性能够有效地激发玩家的创造性思维,但却并不意味着任何谜题解决游戏玩法都具有创造性。聪明才智在《数独》等游戏中并不能派上用场。而 具有创造性的玩家能够在像《蜡笔物理学》(Kloonigames)等游戏中具有更好的表现。

不管是面对何种游戏元素,谜题都具有客观性。当用户尝试着去克服某一障碍时,如果他知道某些可行的方法,他的创造性便会被激发出来,并因此相想出更多不同的解决方法。

这便引起了一个有趣的问题:如果游戏中只存在一种解决方法,玩家是否还会具有创造性?Jonah Lehrer使用复合远距离联想(CRA)去明确人们是何时以及如何使用创造性思维。 尽管谜题只存在一种解决方法,但是人们会使用任何与之相关的理念去解决它。也许只提供一种解决方法的谜题更能激励玩家通过创造性思维去寻找解决方法。

谜题并不能识别并评定创造性。它们只是关于玩家最后想出的解决方法。即使是最具深度的谜题也不能保证玩家能够表现出创造性。谜题只能在游戏中提供给玩家发挥创造性并做 出有趣选择的机会。而游戏将基于结构,关卡设计或时间设定去激发玩家的灵感。

当然了,在我们所谓的益智游戏中不一定总是能够找到具有创造性的解决方法。举个例子来说吧,比起玩《宝石迷阵闪电战》(PopCap),我们在《班卓熊:神奇螺丝》(Rare) 中设计汽车时更能够发挥创造性思维。

创造性的程度则是基于我们所明确的一些元素:例如,《犰狳空间》(Peter Stock)比起之前的《奇妙大百科》,更能激发玩家的创造性。

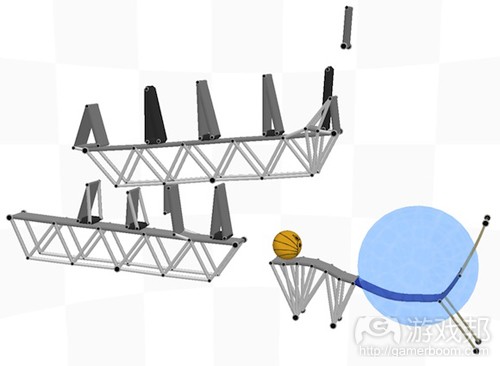

这类型游戏的“始祖”便会在每个关卡中提供给玩家一套特别的道具。例如在《不可思议的机器》的第三个关卡中,玩家便只能使用一个篮球,一颗乒乓球,一只风箱以及一把剪 刀去完成任务。《犰狳空间》也总是提供给玩家七种类型的道具,两种附加选择(电压/压缩器/计时器)以及一定数量的钱。

这种设置能让玩家更轻松地掌握游戏选择,并提供给他们更加自由的空间。同时这么做也能够通过关卡设计去激发玩家的灵感;也就是提供给玩家新问题,让他们去解决新的约束 条件:如距离,高度,预算,障碍,时间等等。

Armadillo_Run_copy(from gamasutra)

许多游戏会给予具有创造性的玩家一定奖励。例如《机器人打擂台》(Gabriel),《链齿轮火箭》www.crackingideas.com),《捣蛋猪》(Rovio)以及《鲍勃的飞船》 (Ludosity)。但也有许多不一样的游戏类型,如《超级格斗》(Nabi Studios),《麦克斯与魔法标记》(Press Play),《魔法对阵》(Arrowhead),《Pontifex》 (Chronic Logic)等。在所有的这些游戏中,创造性都不是游戏的目的,而只是玩家最重要的武器之一。

从这些例子中我们可以看出,创造性需要复杂的游戏系统作为推动力。并且这种开放式复杂性并不只是存在于谜题中。

策略是为了达成某一特定目标而设置的长期行动计划,或者是某一规划。所以它属于游戏玩法的“行动”,尽管面对种种障碍,游戏玩家也会通过制定并执行策略去达成目标。

如你所见,我并不是在谈论即时战略游戏或回合制策略游戏,如《横扫千军》(Cavedog)或《高级战争》(Intelligent System)。实际上,几乎任何一款游戏中都存在策略。例 如在《耻辱》(Arkane),《杀手》(IO),《孤岛惊魂》(Crytek),《丧尸围城》(Capcom)或《刺客信条》(育碧)中的行动方案都具有策略性(或至少具有战略性)。

与解决谜题一样,策略也能够激发玩家的创造性。如果玩家掌握了可行的选择,并能够做出最合理的选择,那么任何意外的发现都能帮助他们到达最终目标。

与解决谜题一样,并非所有的策略都要求玩家使用创造性思维。技巧型玩家也许在许多游戏中能够执行一些简单的策略,但是只有真正具有深度创造性的玩家才能制定出富有成效 的行动计划。例如史上最厉害的象棋玩家在经历了创造性思考后总是会叫出“啊哈”。

ruse(from gamasutra)

如此我们能够将策略和战术总结为是解决游戏中问题的创造性方法。

但是在任何游戏中,玩家需要花多长时间才能想出一个新想法?他们总是会反复使用相同的解决方法;甚至有些玩家会忽视任何创造性思维而解决上百种谜题并赢得上千次对抗。

如果游戏让玩家在一个熟悉的世界中拥有太多自由会出现怎样的情况?

沙箱

沙箱游戏(游戏邦注:指在陪伴者的陪伴和引导的同时,游戏者从玩具架上选择玩具,放进盛有沙子的箱子里创造作品的一种心理游戏)便侧重于给予玩家更多自由:让他们能够 自由决定前进方向,目标以及过程等。

《模拟人生》(Maxis)和《侠盗猎车手》(Rockstar)便属于这类型游戏。这两款游戏最大的区别(除了对于女性角色的尊重)便是,《侠盗猎车手》混合了沙箱游戏与基于目标 的讲故事游戏,而《模拟人生》则更像是一个巨大的玩具箱,不设定任何条款也不存在任何背景故事。

沙箱电子游戏主要是受到“沙箱”的启发。《沙箱》(Pixowl)便是一个很好的例子。

the_sandbox(from gamasutra)

如果继策略和问题解决后,玩家还留有创造性思维,那就该沙箱上场了。的确,这些开放性系统留给玩家许多选择,并鼓励他们去选择属于自己的目标。结果便是,沙箱游戏经常 包含各种类型的策略,战术以及问题解决方法。

沙箱将童年作为最纯粹的创造性的标志——尽管事实上,沙箱游戏玩家的表现与现实沙箱游戏中孩子们的表现并不相同。这些孩子们面对的只是沙子和自己的想象力。如果足够幸 运的话还会有一些玩具,否则便只有一些隐藏的狗粪。

Aldous Huxley曾经写道:“沉默是潜在的智慧表现,就像一个精致的雕塑中一块未被磨削的大理石。”在空荡荡的沙箱中,孩子们就变成了游戏设计师。他们的目标是为自己的游 戏体验设计工具。有时候也会包含某种形式的游戏玩法。

在沙箱电子游戏中,游戏正式开始前总会出现先各种内容,包括角色,环境,行为,能量,控制等。尽管在这里,沙子并不具有任何个性,但是所有的这些元素都将影响着玩家的 心理状态。还有一种更有趣的比较对象,就是让一个孩子独自在玩具店挑选礼物。

游戏主题能够带给玩家灵感,其规则亦是如此。举个例子来说吧,《模拟人生》和《侠盗猎车手》的汽车就不同。在Maxis的游戏中,汽车只是作为一种事件:它们是用于传达角色 的通勤;玩家不需要真正与此发生交互作用。而对于《侠盗猎车手》的玩家来说,汽车则是一种探索道具,运输方式,能够用于撞车,诱骗对象并引爆。

如此便让我们想到另一种创造性形式:也就是利用创造性思维去寻找现有问题的解决方法。有时候找到解决方法也能够引出一个全新的目标。我们也可以将这种机遇称之为创造性 。

任何《侠盗猎车手》玩家都知道,从A点前进到B点是最愚蠢的做法。举个例子来说,尽管在游戏中,唯一与故事有关的目标是到达城镇的另一端,但是任何突发的情境都有可能改 变玩家的优先顺序。例如出现一辆值得偷窃的好车,去埋伏敌对帮派,或在某一场所表演特技。大多数时候,玩家最终都会遭到警察的追捕。而这时候有可能又会出现其它情境( 如遭遇射击)。

你打开《侠盗猎车手:血战唐人街》(Rockstar Leeds)去尝试新偷来的跑车,并最终遭遇了这一情境!

GTA(from gamasutra)

《模拟人生》也是遵循着相同的模式:玩家创造某些事物(主要是人和房子)去维持生计,与别人交流或交换。玩家的计划总是会根据事物的发展以及他们的游戏愿景而发生改变 。大多数时候,玩家都会对游戏系统所创造的情境做出回应:“Will应该邀请邻居共进晚餐吗?Grace想要获得多少优惠?起居室太小了,放不下全新的家庭影音设备;我该如何从 新摆放家具?”

期望值

开放式游戏让玩家能够自由选择前进路径,并呈现出一个布满各种互动式玩具的开阔环境。就如我们所看到的,游戏有时候也会引出一些没有联系或不一致的短期目标。尽管这些 目标也很有趣,但是这种短期的游戏玩法循环却会降低玩家对游戏的期望值。

我们都知道,电子游戏世界通常都是静态的。商人们会一整天在同一个地方等待着,怪物们会漫无目的地游荡,直到被冒险者杀死,非玩家角色则永远不会去碰触宝箱。尽管他们 在游戏世界中好像没什么意义,但是对于让玩家去控制事物的发展变化却非常重要。如果游戏世界中的所有内容总是不断地发生变化,玩家便很难预见自己行动的结果,从而导致 他们难以制定长期策略。

复杂的动态行为会降低玩家的期望值,并同时带给开发者消极影响。当玩家不能预见游戏的发展时,各种漏洞便会相继涌现出来。这便是有关漏洞的定义:软件的某一环节中所出 现的不能预见也不被需要的行为。

跳脱思维框架

当一些不可预见的行为是因为复杂而引起的,那么大多这种行为都属于漏洞。但是如果这些行为在游戏世界中是有趣且具有意义的,那又是怎样的情况?游戏设计师便会皱皱眉, 然后将其称为“意外的游戏玩法”——如此这便算是幸运的漏洞。

关于意外的游戏玩法的两个有名的例子便是,《骇客任务》(Ion Storm)中借助矿山而攀升,以及在许多第一人称射击游戏中利用火箭的冲击力而快速上升到更高的场所。如今, 这种游戏玩法变得更为经典,《军团要塞2》(Valve)的设计师甚至将其整合到游戏中,将其作为游戏的一般技巧。

找到游戏问题的新解决方法需要玩家发挥创造性思维,特别是当他们面对的是意外的解决方法:这时候玩家就必须比设计师更具有创造性。

意外游戏玩法与漏洞之间的界线其实极为狭窄。实际上,它们之间的不同只是停留在道德上:每个玩家都能自行判断某某意外功能在游戏中是否合法。有些玩家认为攀登矿山是不 合理的,因此便会拒绝这么做。就像在每种类型的游戏中,欺骗便是一种道德问题。

但是如果玩家使用欺骗去寻找更有效的解决方法,它便具有创造性。但是我并不是说欺骗是一种游戏玩法,因为它经常会摧毁设计师所设置的各种障碍。而没有了障碍也就不存在 任何游戏玩法。

我们并不是在此讨论黑客行为及其创造性优势,很明显这是发生在游戏以外的行为。而创造性游戏行动只会发生于游戏内部。尽管玩家的目标是来自“游戏外部”:即主要是通过 玩家的想象。但同时也有来自于游戏中的成就或战利品系统。

猜测

内部和外部目标有什么不同?大多数时候是没有差别的。角色要求玩家去打倒boss,成就亦是如此。即使成就与游戏内部的目标并不一致,它也仍是游戏目标,这对于创造性潜能 并没有多大影响。

有时候,成就会激励玩家去猜测目标——即不提供任何描述(或者只是含糊地说明)或将其隐藏在菜单的最最最下方。

就像《成就解锁2》(Armor Games)便提供了许多机会让玩家去猜测自己剩下的目标是否太过不现实,如“死在朝下的钉鞋上”,“表现出绝望”或“悬浮死尸2秒钟”等等。

achievement_unlocked_copy_2(from gamasutra)

猜测是否具有创造性?比起终点,创造性更应该说是过程。即我们的大脑朝着所有方向去寻觅真正解决方法的方法便是创造性。即使世界上的所有玩家最终都会得出一个相同的答 案,但是每个玩家都有可能依靠创造性思维而达到目标。

缺少了成就系统便难以实现猜测,但是如果是缺少目标,猜测也仍将照常运转:因为猜测是一种隐藏功能或秘密领域。所以猜测有可能是创造性思维,也有可能不是。就像许多资 深玩家会为了获得奖励而进行各种猜测摸索,很明显,这种态度便不具有创造性。

猜测能够给予玩家特殊的反馈。让玩家觉得就好像设计师在对自己说:“我们也是这么想的!”通常情况下,这些功能都是使用外生语法。例如,在《王国守卫战》(Ironhide) 第一个关卡中,我尝试着反复点击绵羊,并惊喜的发现游戏具有与《魔兽世界》一样的效果。我朋友也发现,在《狂飙:旧金山》(Ubisoft Reflections)中以超过88mph的速度 驾驶DeLorean是一种非常特殊的挑战。

我们能从桌面游戏中学到什么

着眼于非电子游戏也非常有趣。作为电子游戏开发者的我们还不是很成熟。据说,最早的一款游戏是出现在公元前5000年(甚至在《Crash Bandicoot》之前),即来自埃及的 《Senet》。

电子游戏借助了电脑的帮助而改变了人们的游戏方式。也许这听起来很可怕,但事实却不是如此:呈现图像并播放声音能够帮助玩家发挥想象;管理规则意味着玩家无需为此费神 ;模拟AI角色则能替代人类对手。甚至有时候游戏还会模拟人类玩家的行动(游戏邦注:如实时演示,教程,AI vs. AI打斗等)。

说到这里,你也许会认为我将开始大谈桌面游戏的优点,大谈人类在社会中的地位,或者计算机永远不懂日落之美等等。但不可否认的是,电子游戏也拥有许多很棒的特性,并且 大多数特性都是基于人们对电脑的使用。我并不会通过对比电子游戏和非电子游戏去判断哪一种更加优秀。但是因为创造性较为主观,所以可以确切地说,计算机的出现对游戏系 统带来了巨大的影响。

几乎在每一款电子游戏中,计算机都把控着规则管理。而在传统游戏中,这则是属于所有玩家,或特定玩家(游戏邦注:如游戏控制着,裁判员,银行家等)的任务。这种区别让 我们能在电子游戏中看到更多复杂的规则:除了基于纸和笔的硬核游戏玩家,没有人会想去估算剑撞击怪物的时间。这时候计算机强大的估算能力便派上用场了。另一方面,桌面 游戏并不会利用游戏系统的复杂性去激发玩家的创造性。

我们意识到计算机并不能识别创造性,同时也不能评价道德,美术价值,协商,美感或任何主观意识。而在桌面游戏中,那些可以按照自己的想法去面对这些内容的玩家便能够有 效地应对游戏规则。

似乎桌面游戏将创造性当成是一种游戏目标。但事实上却不是如此。这种能力只是一种手段,而非结果。

当创造性作为桌面游戏的主要机制时,它将致力于实现某些目标,如通过绘画或泥土让玩家猜测一个隐藏的单词;在自由言论中隐藏一些怪异的词;为某一单词想出一种可信的定 义;通过角色扮演而表明自己的看法或帮助别人摆脱麻烦——“角色扮演”在电子游戏中具有多种特点:为角色命名,以一种奇怪的方式交谈,创建属性等等,但它从不意味着角 色的行为会对游戏玩法造成影响。

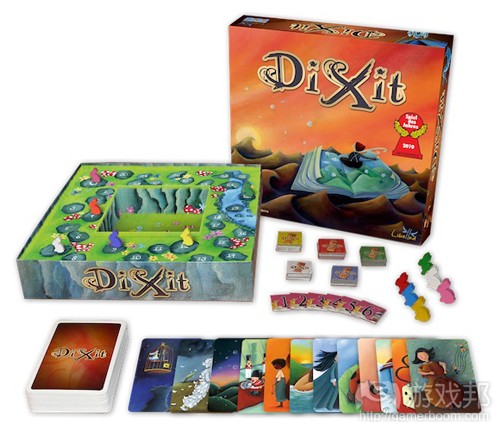

DiXit_copy(from gamasutra)

《Dixit》(Jean-Louis Roubira)是一款华丽且精致的桌面游戏,总是会不断鼓励并奖励玩家发挥创造性。

电子游戏还允许玩家去评估其他玩家的创造性,例如给予其他玩家的定制关卡5颗星的评价。但是这些决定都是发生在游戏之外。在上述桌面游戏中,其他玩家的决定才是游戏中的 决定:将影响着玩家最终的成败。

电子游戏中也有这样的设定。基于现在的社交网站和异步游戏趋势,多人游戏更倾向于让玩家花时间与自己认识或喜欢的人玩游戏。而电子游戏能否效仿桌面游戏呢?当然可以。就像大受欢迎的《Draw Something》(OMGPOP)便是受到经典的《看图说词》(Rob Angel)的启发。《Drawception》(Nihildom)便使用了与传统游戏“纸电话”一 样的原理。还有一些MMO允许玩家通过评价其他玩家的创造性而决定他们的分数,就像《Mamba Nation》(Mimesis Republic)。

我认为这一趋势非常有趣,并且非常适用于社交游戏——尽管许多理念并不是来自于电子游戏中。

在结尾之际,我必须提及两款最适合创造性玩家的电子游戏。

《涂鸦冒险家》让玩家通过打出道具的名字而找到它们:你可以产下一只“蓝色的鸭嘴兽”,让它戴上“潜水镜”,并将其扔到“黑暗的小洞中”。游戏中设置了上千万个单词, 这点真的很让人吃惊。创造性玩家甚至不需要在任何关卡中寻找乐趣,光是在主菜单中他们便能够发挥创造性思维。

《涂鸦冒险家》中有两种类型的关卡。第一种关卡便是让玩家从A点走到B点。当玩家到达终点时都会觉得非常无聊,因为他们至始至终都在使用相同的解决方法;并且因为玩家能 够涂鸦大量的直升飞机和巨型乌贼,所以在这里创造性并不能帮助他们克服任何障碍。

而另外一种关卡类型便能够使用创造性。即玩家需要写下一些相关的道具或生物。关联性主要是基于词汇系统:每种道具都标记着一定的主题,类别,物种以及物理性质等等。这 也是为何当游戏关卡询问我恐怖电影的道具时,我能够使用一批死马去完成电子游戏的挑战。这是多么让人高兴啊!

尽管《涂鸦冒险家》也具有某些缺陷,但它提供给玩家发挥创造性的广阔空间:源自许多可理解的语法(包括日常生活以及各种文化)的大量选择,大量能够刺激灵感的情境,以 及关于关于开发者所设置的各种选择的猜测。

强大的游戏目标

最后,我不得不提到这款吸引全世界上百万名玩家产生疯狂想法的游戏,《我的世界》(Mojang)。

《我的世界》具有创造性的游戏玩法。许多玩家都花费了上百个小时在游戏中挖掘矿山,设计自动化轨道,并创建彩虹教堂。尽管游戏世界充满竞争性,但是却很容易进行改变。 只要进行几次点击,玩家便能够移动山脉,创建城堡并挖掘地下城。

minecraft(from gamasutra)

《我的世界》从未告诉玩家该做什么,这里不存在故事目标,不管是短期还是长期的。《我的世界》并不只是一个关卡编辑器。

游戏总是以一种巧妙的方式去激发玩家内在的冲动。游戏中随处可见的竞争性为玩家呈现出了一个目标,即努力存活下去。他们往往只需要几分钟时间便能够习惯游戏所制造的恐 怖感。如果他们想在游戏中生存下去,就需要找到一个避难地。这便推动着他们去寻找安全地点,从而躲避野兽的攻击。虽然今天的建筑学已经演变成了一种艺术形式,但是一开 始它却只是人们躲避危险野兽的工具。

所以游戏拥有非常强大的目标。玩家可以采取各种方法去获得生存,如利用巨大且坚固的墙壁,铠甲,武器,陷阱等等,所以游戏中总是包含大量的创造性策略。而锻造这些工具 还需要各种原材料,所以玩家必须在游戏世界中不断探索。在探索中他们将遭遇并发现各种事物,并产生更多不同的想法。《我的世界》提供了巨大的机遇让玩家去发挥创造性, 不过因为游戏世界是静态的(除了一些系统化或随机事件,如树木生长或怪物闲逛),所以玩家能够在此发挥长期的创造性。

游戏玩法和游戏世界分享着相同的语法,并混合了独特且让人印象深刻的生物(如爬行动物),被简化的现实机制(如被“加工过”且能够用于制作玻璃的沙)以及经典的虚拟元 素(如缓慢行走的僵尸)。

简单且清晰的游戏语义设置能够让玩家即使在停止游戏后也仍会继续思考游戏内容。

我认为游戏忽略了许多能够推动玩家发挥创造性思维的元素,如砖块堆积,生物系统所支撑的区域相容性,并且未存在一个明确的目标去推动玩家寻找冒险的真正意义(除了获得 生存)——《我的世界》需要一个完整的功能。不过有一点可以确定的是:它有效地结合了游戏玩法与创造性

结论

我们已经阐述了创造性是如何结合早前的理念而创造一些全新内容。灵感是生成这些理念的过程,但是创造性却远远超越了这些理念:这是一种问题解决能力,并要求许多可行的 选择。

另一方面,我们已经创造了要求玩家采取行动去克服种种障碍并达到目标的游戏玩法。

我们必须牢记,计算机并不能识别创造性。所以我们必须提供给玩家足够的空间去发挥创造性,并鼓励他们发挥创造性——要知道创造性可是急不来的。

游戏玩法将为创造性元素腾出更多空间,而不只是玩家一开始想的那样。

毫无疑问,关卡创造者和游戏制作人都属于创造性人士。尽管他们是面向游戏设计创造内容,他们有时候也会走出游戏领域。

通常情况下,定制内容都不会对游戏玩法造成影响。而如果产生了影响,那么玩家的创造性动机和游戏目标之间便会出现各种冲突。

因为创造性作为一种工具而非目的,所以它的最大功效便在于解决复杂的问题,制定策略,战术或开放式系统等。但前提必须是拥有稳定,一致且深层次的游戏玩法系统。

以下便是我们所明确的8种创造性游戏玩法形式:

1.游戏内部角色编辑器,有时候会给予玩家许多深层次且能够相容的选择,以此去决定他们的角色能力和游戏风格。

例子:《孢子》

2.复杂的谜题,有时候会让玩家寻找并使用新的解决方法去解决某一特定的问题。

例子:《犰狳空间》

3.给予巧妙的策略或战术奖励的深层次游戏。

例子:《横扫千军》

4.在开放式游戏中,玩家能够描述他们自己的目标。

例子:《模拟人生》

5.具有各种动态系统的游戏,特别是沙箱,能够有效地刺激玩家发挥创造性

例子:《侠盗猎车手》

6.复杂且一致的游戏系统,能够让玩家使用意外的游戏玩法而发挥优势。

例子:《骇客任务》

7.成功地猜测出游戏的反应便是最大的奖励。

例子:《涂鸦冒险家》

8.电子游戏中很少使用这种方法,即基于其他玩家的评判去决定胜负。

例子:《Dixit》

小结

为什么创造性如此重要?作为人类的一种能力,这是一种天赋,是我们本性的重要组成部分。这一技能能让所有人受益,能够经受鼓励,训练和挑战等,尽管在这一点上我带有一 定的偏见,但是我认为游戏是激发人类创造性的最佳媒介。

我并不只是在说一些严肃的游戏。但是就像Raph Koster在《A Theory of Fun》中所提倡的,游戏就是关于学习。所以创造性游戏玩法对于玩家来说非常有帮助。

如今,关于媒体连接的主要趋势便是对用户的授权:社交网站让用户能够分享自己生活中的各种信息,关卡编辑器让玩家能够按照自己的想法去定制游戏体验,而越来越多手机设 备的出现也意味着电子娱乐已经得到最大化的普及。

对于玩家来说,创造性可以有效地区分盲目地按压按键和富有深刻见解的体验。推动玩家去发挥创造性也能够延长游戏的寿命,并提高其病毒式传播能力:当我在午休时玩《犰狳 空间》,总是有人停在旁边提供各种建议。而最终结果便是这些人也去购买了这款游戏,并开始实践自己的建议。

通过使用创造性去解决一些微妙的问题,我们同样也能够学会如何处理其它主观问题,如道德选择。当游戏玩法使用了与游戏世界一样的语法时,玩家所做出的选择便能够带来深 层次,意外的且具有深刻意义的结果。

相关拓展阅读:篇目1,篇目2(本文由游戏邦编译,转载请注明来源,或微信咨询zhengjintiao)

How can creativity be brought into games — is it even possible? Designer Eddy Léja-Six examines the nature of both creativity and games to get to the bottom of the question: which games allow for creativity, and how do they encourage it?

Creativity and games are among the most important human activities. Children spend a lot of time playing and inventing, often at the same time: “Now you’ll be the bank robber, and I’ll chase you with this invisible dinosaur!”

Many adults will tell you they do not play games because WinMine (a.k.a. Minesweeper) “isn’t really a game.” Others will assure you they are not creative, as “they can’t draw properly.”

In fact, these two activities are part of everyone’s life, and turn out to be as natural and spontaneous as breathing; almost as useful too.

As video game developers, we know how to entertain players and offer them meaningful and emotional experiences. But do we have the necessary tools to allow players to use their creative mind while they play? How did the games that attempted it fare? Should we even try to mix gameplay and creativity?

First and foremost, what is creativity? Here is the definition I could craft that gained the most consensus.

Creativity is the mental process allowing us to find and apply new ideas.

We’ll add chunks to this rather short definition as the article goes on.

Calvinball, a perfect example of (excessively) creative gameplay

Calvin & Hobbes, ? Bill Waterson

So What’s the Plan, Then?

My objective in this feature is to identify if and how gameplay and creativity may work together in video game design. I shall try and cite as many relevant games as possible along the way. Here is a list of the missions I shall have to complete before I reach the en of my quest:

Define creativity further

Define gameplay

Identify how these two have already been used together in existing games

Analyze why those games succeed or fail in their attempt to give the players creative powers

UGC

The most obvious case of creativity in a video game comes from user generated content. While level editors and character customization have been around for a long time now, recent titles such as Media Molecule’s LittleBigPlanet have given the players tremendous creative opportunities.

Let us look at user generated content and the way it can be considered as creative gameplay.

Playtesting Faceez

At Neko Entertainment, we developed a DSiWare app called Faceez, in which users may mix, accessorize and animate faces from photographs. It is the only “non-game” I have ever worked on, but it requires a lot more creativity from the user than all the games I have designed. In fact, the whole app is a character customization menu.

Of course, the difference between an app and a game is gameplay. So Faceez is never going to be a good example of how gameplay and creativity may or may not mix. But it gave me a lot of clues about user creativity in software.

If someone asks to use your face to promote the app you’ve designed, believe me, you should say no.

Playtesting Faceez was particularly interesting, as two distinct behavior patterns emerged: Users combining game assets (accessories and animations) began by empirically browsing the available options, and then used the random button for a while before they felt really comfortable enough to be creative. Conversely, when mixing faces from their own photos, people had creative ideas right away. Why is that?

The faces that users mix come from pictures of the people close to them. The difference with other assets is that users already know them. Once they grasp how the system works, they immediately come up with ideas using the photos they have taken and the ones they could take:

“My sister with my big eyebrows…”

“Me with my boss’ hair!”

“Oh, and I could take a picture of Brad Pitt and mix him with me!”

“Wait, what about a mixture of me, Brad, and my next door neighbor all inside the face of a chimp?”

And so on…

Applying those ideas may require testing, validation, mind changing, and chance findings… But at some point in the process, there are ideas — creative ideas.

In the opposite, before a user may have the creative idea, for example, to make a Faceez use a tuna fish for swashbuckling, she either:

Must know, from experience, that the app contains a tuna accessory and a sword-fighting animation.

Or guess those two options must be available — I mean, only crappy games don’t feature tuna! — and then actively search for them. Software users rarely think like that, because it is often disappointing. Of course, when guessing works, that is an awesome experience (we shall get back to that later on).

To be creative, a player must know the available options well.

The downside is that the more options the players have, the longer it takes to learn and master them. Or does it?

What is Your Name? What is Your Quest? What is Your Favorite Color?

Imagine how Rare’s avatar editor for the Xbox 360 would feel with only four haircuts, three nose shapes, two shirts… Could anyone get creative in that context? Could a player try and mix those elements to meet the result she imagined? Or would any user just go for the least inappropriate result?

Creativity may only happen if there is a large number of choices.

Already, there seems to be a conflict: to allow for creativity, the users must easily understand the tools we give them. So to keep it simple, we might want to reduce the number of options to learn. But that would reduce the amount of available choices, thus reducing creative potential.

Character customization in Adult Swim’s Five Minutes to Kill Yourself is brilliantly designed so that creativity is totally impossible; this is achieved by drastically reducing the number of meaningful outcomes, and it suits the depressing atmosphere of the game world perfectly.

In the indispensable The Art of Game Design, Jesse Schell shares a very interesting personal experience about indirect control:

In my amusement park days, I sometimes worked in the candy store, in front of a big display of 60 flavors of old-fashioned stick candy. A hundred times a day, people would come in and ask, “What flavors do you have back there?”

At first, I thought I would be a smart aleck, and recite all 60 flavors — as I did this, the customer’s eyes would get wide with fear, and right around the 32nd flavor they would say, “Stop! Stop! That’s enough!” They were completely overwhelmed by so many choices. After a while, I thought of a new approach. When they asked about the flavors, I would say, “We have every flavor you can imagine. Go on, name the flavors you would like — I’m sure we have them.”

At first they would be impressed with this powerful freedom. But then they would furrow up their brows, think hard, and say, “Uh… cherry? No, wait… I don ’t want that… Hmm… Peppermint? No… Oh, just forget it,” and they would walk away in frustration.

Finally I figured out a strategy that sold a lot of candy sticks. When someone would ask about the flavors, I would say “We have just about every flavor you can imagine, but our most popular flavors are Cherry, Blueberry, Lemon, Root Beer, Wintergreen, and Licorice.” Thy were delighted at having the feeling of freedom, but also glad to have a small number of attractive choices; in fact, most customers would choose from the “popular six,” a list I made up, and a

list I would change frequently to help ensure the other flavors didn’t get too old on the shelf.

Indirect control may be used to help players overcome the overwhelming sensation of creative freedom. In fact, default settings and “randomize” buttons do just that. They tell the player: “You could design any character you want, or you might also just use that one.”

Why Choose Between Lipstick and a Moustache?

Another classic solution to that problem is to reduce the number of options, but allow players to combine them so that there still is a large number of possible meaningful outcomes. For example, Warcraft III (Blizzard) allows players to pick a color among 12; there are just 12 possible results. Players of Titan Quest (Iron Lore) may choose their clothes color among five choices per gender.

We may evaluate the combinatorial depth of a system by calculating a ratio of outcomes per option: in Warcraft III, the player has 12 options and there are 12 possible results. 12/12=1, so its ratio is just 1. There is no combinatorial depth at all. Titan Quest has seven options in total (male, female, white, brown, blue, gray and red) and 10 possible outcomes. This means Titan Quest’s ratio is 10/7=1.42.

The ability to combine options may create a great difference between the number of options to master and the number of meaningful outcomes [1]. It’s interesting to see that it suits those games’ ambitions: Just picking a color hardly qualifies as customization: Blizzard’s designers needed different colors to make each player different, and Warcraft III allows up to 12 players. Adding the choice between male and female, as in Titan Quest, is the beginning of combinatorial customization. (Later in the game, the appearance of characters mainly varies due of their equipment and active buffs.)

LittleBigPlanet may be the deepest game ever when it comes to customization and creation.

This way of combining options illustrates how game users can only be creative by combining things that already exist. Put that way, it seems very limited. But cannot the same thing be said of any creative process? As Robert I. Sutton of Stanford University points out, creativity is making new things out of old ones.

Creativity is making new things out of old ones.

Do ideas need to be new in order for them to qualify as creative? Well, creativity is a mental process, above anything else. If the players think they invented something the world has never seen (“Ooh, how about a Barack Obama Mii!”), then it just feels that way. So yes, creative ideas need to be new for the creator — not for the world.

But as I said, Faceez did not have gameplay. Other very creative titles, such as Elektroplankton (Indies Zero) or Art Academy (Headstrong), will not help either. In order to find if and how user generated content is a part of gameplay, we must first define the word.

[1] I keep mentioning “meaningful” outcomes because moving the character’s jawbone one millimeter down will not result in a perceptible difference.What is Gameplay?

All Gamasutra readers have a good grasp of what a video game is — so while there’s room for argument, I will not even bother to redefine it here. Warning: this article contains ideas that some readers may find offensive. If you don’t think The Sims is a game, look away now!

We all know games may be “used” to be creative, just as a magazine may be used for collage. We need to find out if creativity may occur during gameplay. Surprisingly, there is no easy consensus on the word “gameplay”. Tom Heaton wrote: “Most people could agree on a rough definition along the lines of ‘the gamey bit of the game.’ But disagreement will quickly arise as to what gameplay actually is, what its elements are, why one feature contributes gameplay and

another doesn’t.”

For the purpose of this article, I will try to build my own personal definition. Gameplay is the core of the game’s flow. Therefore, gameplay is the heart of the activity of playing.

Here are a few examples of gameplay actions in a video game: exploring a map to find hidden secrets, moving a white rectangle to bounce a white square back, trying to beat your own time record on Track D with Car #42, equipping a new shield for increased armor class, or climbing a large mountain to find out how far you can see.

So what isn’t gameplay, then? For example: navigating a menu to choose a game mode, watching a cutscene, modding, turning the volume up, or waiting for an opponent in a matchmaking lobby.

Gameplay occurs when players:

- Have an objective

- Cannot immediately reach their objective because of the obstacles on their way

- Have to undertake actions to overcome these obstacles

Of course, the details may vary greatly from game to game: there may be several objectives at once, the players may choose or invent their own objectives, the obstacles can consist of challenges, rules, labyrinths, puzzles and many more, and the actions may range from very intellectual choices (“is it the right moment to upgrade my base to Tech Tier 2?”) to mere reflexes (“Do a barrel roll!”)

The Impact of User Generated Content on Gameplay

More and more, games allow players to create their own characters, their own levels, and their own worlds. The amount and depth of available options determine the user’s freedom. In most editors, the number of possible outcomes is just dizzying.

Many of those editors do not partake of gameplay: for instance, building levels and sharing them turns the player into a level designer. And level design, as you probably know, is not a game in itself.

Sometimes, gameplay may affect those editors, most commonly by unlocking options and items (“Well done, you’ve completed Level 2! Here is a nice 3×2 platform to build new levels!”) But while, in this case, gameplay opens the door to creativity, it does not make creativity a part of gameplay. When a poker player spends the money she won, she is no longer playing poker.

Other times, gameplay may limit creativity. For example, Lionhead’s game The Movies puts the player in charge of a production studio. A rich tool allows editing movies, but the player can only cast the available actors, use the already unlocked sets, etc. Yet again, the creative efforts one may put in one’s movie will not impact the gameplay. It may just result in a very nice video to share online.

Games such as Audiosurf (Audiosurf LLC) and Vib-Ripple (Nana On-Sha) make level design out of assets such as music or photos. Even if these are creative assets, they are usually created outside of the game (and most of the time not by the player. The Prodigy is my favorite Audiosurf level design team.)

All Points Bulletin (Realtime Worlds) gives you the amazing power to turn your gun-toting character into a male pornstar from the ’70s with a blue moustache.

The most common customization feature allows the player to craft the main character’s appearance. This kind of editing is usually very deep but has no impact on gameplay: for example, I once gave Commander Shepard (from BioWare’s Mass Effect) the face of a skinny grumpy guy with distasteful facial hair, but understandably, it did not have any impact on the way people reacted to him.

Of course, gameplay is not everything in a game. The character’s appearance has an impact on the play experience; otherwise the greatest game studios would never bother to develop deep customization features. Playing as a unique custom charcter changes the player’s whole impression of the game… and it may prevent a MMO player from realizing that she is just player #65535. Sharing creations online is also amazingly satisfying. Again, there is no doubt this kind

of creativity is very rewarding, but it is not directly gameplay-related.

May I See this Plasma Cannon in Another Color?

However, it may happen that character editors have an impact on gameplay. In Bethesda Softworks’ Skyrim, players can pick a character race among 10. This choice influences stats, skills and some of the NPC’s reactions. It will also determine what the visual customization options are. For example, Khajiits are humanoids with cat-like heads. The player may customize many facial features, but the character will always look like a cat.

In this example, we see the player’s choices have 10 different gameplay-related outcomes, and billions of purely aesthetic possible results. It is often the case during character creation: there are fewer options pertaining to the gameplay (such as skills, classes, perks) than visual options (colors, clothing, facial traits).

Why is that? Well, any designer who has actually fine-tuned a game system knows that the more different elements you have, the harder it is to find a balance. Adding just one new skill too late during the production may ruin the whole experience for players, whilst adding 15 moustache shapes just one week before Gold Master seems quite safe.

…Unless of course we are talking about the Fable games (Lionhead), in which facial hair patterns grant bonuses. Remember guys: a Sheriff Moustache makes you attractive but scary!

It now seems gameplay customization hardly gives enough freedom for players to get creative: without a large number of options, creativity is impossible. And allowing a large number of gameplay-related options is quite difficult. There are a few noticeable exceptions, thogh.

Maxis’ Spore Creature Creator may be the deepest character creation tool ever made. It allows the user to spawn trillions of totally different creatures. Doubtlessly, any editor allowing creating a seven-legged creature with three noses is indeed an amazing creative tool. What’s more, the chosen elements have an impact on the creature’s abilities: wings allow the creature to fly, nasty big pointy teeth make it carnivorous, and nimble feet will make it the best dancer in the ecosystem.

Several other games allow character customization to have deep gameplay effects, such as Impossible Creatures (Relic) or Freakyforms (Asobism). When using those editors, a conflict may emerge between the will to create original creatures and the desire for efficiency. Sometimes this conflict will result in even more creativity, but it may as well get frustrating and illogical: imagine yourself creating a perfect predator, a huge carnivorous brute with massive claws. You then check its stats and, because you used basic Level 1 claws, it has weak combat abilities…

After mentioning this to a friend, I realize he had the same problem, and came up with the same (creaive)idea as me. He added a tiny appendix granting a Level 5 attack ability (the maximum value) hidden between the creature’s legs, where no one would see it. That way, the creature was the fighting juggernaut he expected; yet it did not ruin the look he wanted it to have, notwithstanding the tiny razor-sharp genitalia.

The creature on the left has Level 1 attack options (Strike, Bite and Charge), while the creature on the right has these same attack options at Level 5. Does the single-legged teal freak really look five times more powerful in close combat than the purple hulking beast?

The same phenomenon (synergy or rivalry between customization and gameplay) appear in other games. Players of SimCity (Maxis) may discover that the town they always wanted to build is not viable at all. Discovering that might be an interesting experience (“Oh, people will not pay twice as much tax for a magnificent park!”) but even in that case, following wacky ideas will actually reduce gameplay efficiency. The players then realize their two objectives do

not mix: creating a “me-town” and avoiding bankruptcy.

On the contrary, players may later get to understand the gameplay better and come up with creative and efficient design. The same goes for Spore. The creatures players build later in the game tend to be consistent with the game’s loic and at the same time be noteworthy creations, even for those who do not know how the game works.

Players who get to know a game’s rules, as well as the game world’s logic, are less likely to make ridiculous mistakes — such as giving a very stealthy character goggles with three bright green lenses.

The Grammar of Creativity

It is a well-known established fact throughout the many-dimensional worlds of the multiverse that most really great discoveries are owed to one brief moment of inspiration. There’s a lot of spadework first, of course, but what clinches the whole thing is the sight of, say, a falling apple or a boiling kettle or the water slopping over the edge of the bath. Something goes click inside the observer’s head and then everything falls into place. The shape of DNA, it is popularly said, owes its discovery to the chance sight of a spiral staircase when the scientist’s mind was just at the right receptive temperature. Had he used the elevator, the whole science of genetics might have been a good deal different.

- Terry Pratchett, Sourcery

What is the fundamental distinction between aesthetic and gameplay-efficient designs? In fact, they do not use the same language. When players create Spore creatures tailored for gameplay (with all the skills necessary for a certain play style), they think about the rules of the game, about the obstacles they may encounter, about their ultimate goals and the way they are going to reach them.

On the other hand, what motivates players to design creatures before they even know the gameplay that well? Indeed, when they create their first Spore creature to try the game out, they do not have a clear idea of what they will face. Yet, is it the same feeling as modeling a creature from scratch in Zbrush? Not at all.

For starters, it is easier with a creature editor, as you are guided and never experience a “blank page” syndrome. But the main difference is probably that players know their creature will come to life (even if they do not know if it is going to survive for long). When designing their creature, players imagine how it would fare in what they expect the game world to be.

If creativity is the ability to combine old ideas to generate new ones, the question is: Where do these old ideas come from? Most gameplay-related customization systems are very narrow and limited, and do not allow a large enough number of options for players to be creative. Ideas from other domains usually do not have much value. The only pertaining grammar is strictly endogenous.

When the editing tools are deep enough to allow for designs based on a creative idea, as in Spore, the player uses a much wider grammar. It may be a combination of elements from the real world (“behold the butterfloctopus!”), the game world (“tiny flying animals every other creature wants to eat”), from everyday life (“a clone of my ugly math teacher”), from fantasies (“a giant penis”), from cultural icons (“Homer Simpson with Wolverine’s claws”) or even from many different grammars at once (“flying Homer with a giant penis and a pulley in the middle!”)

Behold the butterfloctopus!

This is exactly why Faceez’ photos allow users to be creative right away. Not only do they allow for a larger number of options, but they use a grammar the player already knows.

Of course it is always possible to create something that will work in creative grammars as well as the gameplay grammar. Sometimes, efficiency brings its own aesthetic value, and people familiar with the game will be able to decipher the creation’s characteristics by just looking at it (“I see you’ve designed a social creature; nice idea to make it a fast sprinter, just in case!”)

Wherever ideas come from, the ability to connect concepts from very different worlds is a cornerstone of creativity. Or more simply:

Creativity requires inspiration.

Inspiration mainly describes the way the brain connects existing ideas to build new forms, concepts, actions… The process is mostly unconscious, and has the reputation of coming and going. While this is true, there are several ways it can be stimulated.

We have already discussed how randomize buttons may familiarize players with the available options. Randomness may also give ideas, just as browsing Google Images or listening to people during a brainstorming session. An arbitrary flow of concepts gives food for thought.

Arbitrary situations may have the same effect: When the only tool you have is a hammer, any Celine Dion CD you come across may give you ideas. Situations do not only give players elements to work with, they also imply a certain number of constraints. Sometimes constraints guide inspiration; sometimes they destroy it. A gameplay grammar brings constraints to the customization process. These constraints may help new ideas appear, or they may just prevent and kill any creative ambition.

It turns out user generated content allows for inspiration and creativity but is not strictly a part of gameplay. Few games allow creations to have a deep impact on gameplay, and that may result in synergy or conflict.

Those conflicts come from this unavoidable fact: all players have at least one gameplay objective. User generated content may or may not mix well with it. This raises an important question: What is the purpose of creativity?

The Muses’ Secret Agenda

For any of us, creativity evokes insight, epiphanies, imagination. This is indeed a very important aspect of creativity: Without the ability to have ideas, creativity cannot exist.

But creativity does not stop there. It has a purpose. That purpose may fluctuate, be unconscious, arbitrary, silly… but it still is a purpose. If you do not have an objective, there is just no point in being creative. Creativity is inspiration plus perspiration.

On a theoretical level, having an objective and having a problem is just the same thing. Of course they do not sound the same at all. For example, I may accuse you of creating your own problems, and that would sound bad. Or I could praise you for deciding of your own objectives, which sounds a lot better. While these feel different, I am really talking about the same phenomenon: creating your own problems gives you objectives. Similarly, by picking your own goals, you will face the new problems of how to reach them.

Creativity is a problem-solving ability; it requires a purpose.

ACME statistics show that coyotes are 78% more creative when they are starving. (Citation needed)

Life is full of goals: ambitions, dreams, needs, professional challenges and requirements, social obligations… So which real-life problems may the ability to “find and apply new ideas” solve? Plenty: closing a business deal, getting your children to eat vegetables, coming up with a funny joke to break the ice, getting all the luggage in the car, writing a 10-page composition on a Sunday evening, opening a strongbox on a desert island, and so many more.

If having a purpose and looking for a solution to a problem are the same, then gameplay and creativity seem very close. Moreover, the above examples are all quite challenging. Yet, are they similar?

Any game has at least one goal, even if the player had to invent it. Otherwise, it would not be a game at all. But it turns out real-life problem-solving is different from gameplay problem-solving. During gameplay, the player has limited options and is constantly judged by the game.

You may think this depends on the game but, in reality, it does not. Remember, we are comparing games to real life here: even the most amazing free-roaming physics-based massively multiplayer triple-A game contains extremely simple and limited objects and systems when compared to the real world.

What would happen if creativity were deemed the objective of the game? Let us look at Create (EA Bright Light) to find out.

Creativity for the Sake of It

Create is a mixture of Incredible Machine-like puzzles, contraption-building challenges, and highly customizable environments. While this title is a good puzzler and contains hundreds of different customization and/or gameplay items to unlock, it fails to reach the objective displayed on Electronic Arts’ website: “Create tracks your creativity and rewards you for it.”

The game features special challenges called “Create Chains”: the player is rewarded for using a specific set of tools in a given level. Apparently, the ambition of Create Chains is to give players many opportunities to be creative, and thus get them to know the available options better. These options are quite comparable to those of a level editor, but they are entirely built-in and use the same interface as the problem-solving gameplay — just as games from the Trackmania series (Nadeo) brilliantly gives players a level editor interface to design the most efficient track they can.

In fact, creativity is not the Create Chains’ real objective. The real hardcoded objective is “use each of these tools enough”. The player may be rewarded for picking any option and clicking randomly in the scene: the challenge has been completed but there has been no creativity. The challenge is a no-brainer.

The player simply gave the game what it wanted in order to keep playing.

At the top, you can see the situation Create gives you as a starting point for a Create Chain in level 1: Theme Park. The two other pictures show different “solutions” to the challenge, equally valid for the game system, but one of those is clearly more creative than the other.

We have seen how inspiration cannot be forced. So we understand how a game cannot ask a player to be creative on demand (“Be creative! NOW!”)

You cannot just make creativity happen.

Even if players are willing to be creative, they may not be able to do it on demand. They may need time. But let’s admit a given player succeeds in being creative, what happens then?

IF CREATIVITY>0.5 THEN GOTO 10

Create is unable to rate creativity. No existing video game could. Even fellow human beings are sometimes very poor at assessing another person’s ideas — as developers, you probably know about that problem. How could a basic video game AI crack such a subjective question?

Of course, games often pretend to acknowledge the players’ sensitivity, for instance when judging the player’s interior design (as in Nintendo’s Animal Crossing) or when reacting to the name you just typed in: “Bollocks? My, what a pretty name!”

In the first level of Duke Nukem Forever (3D Realms), this AI-controlled Earth Defense Forces soldier seems to approve the cunning plan I’ve written for him on the whiteboard.

Nintendo’s Wii Music has a very interesting approach. It allows the players to pick instruments, play the chosen track, design a cover, and then the system asks them to rate their own work, with no limitations whatsoever. The designers knew the game was unable to judge the music’s quality, so the only pertinent opinion is the players’.

Creativity cannot be identified or rated by a computer.

If creativity cannot be identified by the computer, it cannot reward it and more importantly, it should never punish players for not being creative. Even preventing the player from continuing to play is a slight punishment.

We have now defined creativity in a satisfying way. Let us gather all the fragments so that we can forge the ultimate definition of creativity.

Creativity is the mental process allowing us to find and apply new ideas.

To be creative, a player must know the available options well.

It may only happen if there is a large number of choices.

Creativity is making new things out of old ones.

It requires inspiration.

It is a problem-solving ability; it requires a purpose.

You cannot just make creativity happen.

It cannot be identified or rated by a computer.

Ironically, Create does a good job of allowing a form of creativity in some of the puzzle-solving levels. It does not mean that any puzzle-solving gameplay is creative. Brilliant ideas will not make you better at Sudoku. But arguably, creative players fare a lot better in a game like Crayon Physics (Kloonigames).

As any gameplay element, puzzles have an objective. Users may be creative when trying to overcome the obstacles if they know the available options and may come up with many different solutions.

That raises an interesting question: can a player be creative if there is only one possible solution? Jonah Lehrer presents Compound Remote Association Problems as a way to identify when and how the creative mind is used. These puzzles have only one solution, but the mind uses inspired idea associations to solve them. A puzzle with only one possible solution may allow a player to find this solution in a creative way.

Puzzles do not try to identify and rate creativity itself. They only care about the solution the players come up with. Not even the deepest puzzle may guarantee the players are going to be creative. It may only give them opportunities for creativity and interesting choices within the gameplay’s endogenous grammar. Games may also encourage and stimulate inspiration by their structure, their level design or their time scale.

Of course, we do not always find creative problem solving in the games we would describe as puzzle games. For instance, there is more room to be creative when designing a vehicle in Banjo and Kazooie: Nuts and Bolts (Rare) than in Bejeweled (PopCap).

The degree of creativity depends on the factors we have identified: for example, Armadillo Run (Peter Stock) allows for much more creativity than its timeless predecessor, The Incredible Machine.

The ancestor of the genre gives the players a specific set of items in each level. For example, Level 3 of The Even More Incredible Machine must be completed using only with a basketball, a tennis ball, a bellows, and a pair of scissors. Armadillo Run almost always gives the same seven types of items with only two added options (tension/compression and/or timer) and a specific amount of money.

This makes learning the options easier and gives the player loads of freedom. It also does a very good job of stimulating inspiration via the level design’s initial situations; in other words, by giving the players new problems to solve with new constraints: distance, height, budget, obstacles, timed events, etc.

Armadillo Run is a puzzle game so rich it allows for creative thinking.

Many games reward creative ideas. Robot/Contraption builders are a good example: Robot Arena (Gabriel), Sprocket Rocket (www.crackingideas.com), Bad Piggies (Rovio), and Bob Came In Pieces (Ludosity). But there are many others in different genres: Toribash (Nabi Studios), Max and the Magic Marker (Press Play), Magicka (Arrowhead), Pontifex (Chronic Logic)… In all of them, creativity is not the game’s purpose, just one of the player’s most valuable weapons.

From these examples, it appears creativity requires complex gameplay systems to emerge. Is this rich open complexity exclusive to puzzles?And then I Had an Idea: Shoot That Alien!

Strategy is a long-term plan of action designed to achieve a certain goal, or the act of devising such a plan. As such, it belongs to the “actions” of gameplay. To reach their goal despite the obstacles, the players invent and apply strategies (among other actions such as exploring, solving riddles, monster grinding…)

As you see, I am not strictly talking about RTS or turn-based strategy games such as Total Annihilation (Cavedog) or Advance Wars (Intelligent Systems). In fact, strategy is a part of almost any game. For example, deciding of a course of action in Dishonored (Arkane), Hitman (IO), Far Cry (Crytek), Dead Rising (Capcom), or Assassin’s Creed (Ubisoft) can be strategic indeed (or at the very least tactical).

Strategy is as likely to allow for creativity as it does puzzle solving. If the players master the available options and must make clever choices, then serendipity may help them reach their objectives.

As with puzzles, not all manners of strategy ask for inspiration. A skillful player may prevail with a simple and basic strategy in many games, but only insightful creativity allows for brilliant plans of action. As an example, the greatest chess players throughout history gave their names to openings they invented. They must have had those “a-ha” moments that characterize creativity.

We can therefore conclude that strategy and tactics are potentially creative ways of solving gameplay problems.

But for how long can players come up with new ideas in any given game? They shall soon be applying the same solutions over and over (Zerg rush!) What’s more, a given player may solve a hundred puzzles and win thousands of battles without being truly creative.

What would happen if you let the player a very large freedom in a familiar game world?

Sandboxes

Sandbox games focus on giving players a great deal of freedom: freedom to decide where to go, what to do, and how to do it.

The Sims (Maxis) and Grand Theft Auto (Rockstar) are good examples of this trend. The main difference between those two series (apart from the dignity of female characters) is that Grand Theft Auto mixes sandbox and traditional story-driven goal-oriented gameplay, while The Sims is a giant toy box, with no obligations and no background story at all.

Sandbox video games are inspired by, err… sandboxes. Here is a good example called… The Sandbox (Pixowl).

If strategy and complex problem solving leave room to the player’s creativity, so do sandboxes, only more. Indeed, these open-ended systems give a lot of options to the players and encourage them to choose their own objective. Consequently, sandbox games often include some forms of strategy, tactics, and problem solving.

The name “sandbox” uses childhood as the ultimate symbol for sheer creativity, within reason — despite the fact that a sandbox player does not behave like a child in a real-life sandbox. Those children have nothing but their imagination and sand. If they are lucky, they have a few toys as well. If they are not, maybe a few hidden dog turds.

“Silence is as full of potential wisdom and wit as the unhewn marble of a great sculpture”, Aldous Huxley brilliantly wrote. In the desert of an empty sandbox, children become game designers. Their goal is to devise the tools for their own meaningful play experience. It sometimes includes some forms of gameplay.

In a sandbox video game, there usually is already a lot of content in the game before it even begins: characters, environments, behaviors, powers, controls, etc. While sand has no personality at all, these elements have a great influence other the player’s state of mind. A better comparison would be that of a child alone in a toyshop. So many things to try out!

The game’s theme gives players ideas, but so do its rules. For example, motorized vehicles are very different in The Sims or GTA. In Maxis’ game, vehicles are mere events: they are a simple depiction of commuting, and that’s that. The players do not even try to interact with them. GTA players, on the other hand, soon find out that vehicles may be used as quest items, transportation modes, battering rams, decoys, explosives…

This brings our attention to another form of creativity: so far, we have described how the creative mind can find solutions to an existing problem. Some other times though, finding a solution makes a new objective appear. Let us call that opportunity creativity.

Any GTA player knows that going from A to B is the best way to have silly ideas. For example, even though the only story-related objective is to reach the other end of town, suddenly a situation arises that changes the player’s priorities. It could be a very nice car to steal, a rival gang to ambush, or just the perfect spot for a stunt. In most cases, the player ends up being chased by cops. And from there, other situations arise (being shot for example).

You just launched GTA: Chinatown Wars (Rockstar Leeds) to try your freshly stolen sports car and you end up in this situation: typical!

The Sims follows the same pattern: things players create (mainly people and their home) keep on living, interacting, changing. The players’ plans are always shifting according to what happens and how their Sims’ wishes evolve. Most of the time, players react to situations generated by the game system: “Should Will invite his next-door neighbor to dinner? How may Grace get the promotion she wants? The living room is too small for a new home video system; how can I

rearrange the furniture?”

Anticipation

Open-ended games leave the players the freedom to choose their path and provide a rich environment with lots of highly interactive toys lying around. As we have seen, it may sometimes lead to a series of short-term objectives with no connection or consistency. While this is fun indeed, these short-term gameplay cycles reduce the player’s anticipation.

As we all know, video game worlds are often extremely static. Merchants wait at the same spot all day, monsters just wander aimlessly until adventurers kill them, and NPC’s never loot chests. Though it makes no sense in those game worlds, it is necessary for players to control what happens. When everything is dynamically changing, they cannot anticipate the results of their actions, and this leaves little room for long-term strategies.

Conversely, complex dynamic behaviors decrease the player’s anticipation. Unfortunately, they have the same effect on the developers. And when we fail to anticipate how the game will behave, this leads to a larger number of bugs. In fact, that’s the definition of a bug: an unforeseen and unwanted behavior that emerges in a piece of software.

Thinking Outside the Box

When complexity leads to unexpected behaviors, most of them are bugs: they are unwanted. But what if those behaviors actually turn out to be interesting and make sense in the game world? Then the game designers turn their frown upside down and start calling it “emergent gameplay” — lucky bugs, if you will.

Two famous examples of emergent gameplay are the ability to use wall mines as steps to climb up (Ion Storm’s Deus Ex) or using the blast of a rocket to “rocket jump” to very high places (various FPS). Now this move has become a classic, and has even been integrated as a perfectly normal technique in Team Fortress 2 (Valve).

It takes a creative mind to find new solutions to gameplay problems, especially when these solutions are emergent: players even need to be more inventive than the designers.

The frontier between emergent gameplay and loopholes is quite thin. In fact, the distinction is purely moral: every player judges if such and such emergent features are a legitimate part of the game. One could argue that mine-climbing makes no sense, and therefore refuse to use it. As in every type of game, cheating is a moral issue.

Still, the act of cheating can indeed be creative when it implies finding a clever workaround. But I would not qualify cheating as gameplay, because it usually removes all obstacles intended by the designers. Without obstacles, there cannot be any gameplay.

We will not discuss hacking here and its creative merits, as it clearly happens outside of the gameplay. Creative gameplay actions can only happen inside the game. We have already seen though that the player’s goal may come from “outside the game’s box”: from the player’s imagination, mainly. But it may also come from an achievement or trophy system, for example.

Guessing

What is the difference between internal and external objectives? Most the time, they are the same. A character asks the player to beat the boss, and an achievement asks the same. Even when an achievement is not consistent with in-game goals, it still is a gameplay objective, and this has no impact on creative potential.

But achievements may sometimes encourage players to guess what the objectives are. They do that by giving no description (or a very cryptic one) or just by being hidden away in a sub-sub-sub-menu.

With 250 achievements such as “die on downward spikes”, “look hopeless”, or “suspend a corpse for two seconds”, Achievement Unlocked 2 (Armor Games) gives you many occasions to guess how silly or surrealist your remaining objectives are.

Is guessing creative? Again, creativity is more about the path than the destination. The way your brain sniffs in all directions to find the solution may be creative. Even if every player in the world will end up with the same answer, each player may or may not have been creative reaching it.

Guessing may happen without an achievement system. It may even work without an objective: guessing about hidden features or secret zones. Again, that may or may not be considered creative. Most seasoned gamers check behind waterfall for bonuses, but that attitude is clearly non-creative.Guessing gives unique feedbacks to the players. They feel as if the designers are telling them, “Yeah, we thought about that too!” Usually, these features use an exogenous grammar. For example, in the first level of Kingdom Rush (Ironhide), I tried clicking sheep over and over, and I was thrilled to discover it had the same effect as in Warcraft. Similarly, a friend of mine was very excited when he discovered empirically that driving a DeLorean over 88mph in Driver San Francisco (Ubisoft Reflections) unlocked a special challenge.

What We May Learn from Board Games

Looking at non-video games is always very interesting. We, video game developers, are a very young species. The Egyptian game of Senet is said to be one of the first games ever, and apparently dates to around 5,000 BCB (Before Crash Bandicoot).

Video games changed the play paradigm by having computers assist or replace humans. It sounds creepy, but it really isn’t: displaying graphics and playing sounds assists the player’s imagination; managing the rules means the players do not have to do it; simulating AI characters replaces human opponents [2]. Even the human player’s actions are sometimes simulated (real-time demos, tutorial examples, AI vs. AI fights, etc.)

At this point, you may suspect that I am going to rant about how board games are better, about the place of human in society, and the fact that computers may never understand the beauty of a sunset… Not at all: video games have a lot of cool specificities, and most of them come from the use of computers and what that allows for. I do not compare video games and non-video games to determine which is better. But creativity being highly subjective, the presence of

computers has a large impact on the game system.

In almost every video game, a computer is in charge of managing the rules. In more traditional games, this has to be done by all the players or by a designated player (the game master, the referee, the banker, etc.) This difference allows for much more complex rule sets in video games: apart from hardcore pen and paper role players, no one would enjoy calculating the chances for a sword swing to hit a monster when it is influenced by a dozen variables. So the computer’s enormous calculation power is put to good use. Board games, on the other hand, seldom allow the kind of creativity that emerges from the game system’s complexity [3].

We have seen about Create that a computer is unable to identify or appraise creativity. The same goes for morality, artistic value, negotiation, aesthetics or any other subjective matter. In a board game, the players, who deal with these matters as they see fit, handle rules intelligently [4].

Board games, it seems, could just treat creativity as the game’s goal. But often they don’t. Again, this ability is a means, not an end.

When creativity is a major game mechanic of a board game, it serves a purpose such as making someone guess a hidden word by drawing or modeling clay (Cranium, Richard Tait & Whit Alexander), hide a few weird words in a free speech (Nonsense, Véronique Houbaert & Bernard Ralet), coming up with a believable definition for a word (The Dictionary Game), role playing to make a point or get oneself out of trouble (The Werewolves of Miller’s Hollow, Philippe des

Pallières & Hervé Marly) — contra this last example, “role playing” may mean a lot of things in a video game: giving your character a name, chatting in a weird way on ye olde public channels, building stats… but it never implies that your role playing has an impact on gameplay.

Dixit (Jean-Louis Roubira) is a gorgeous and subtle board game in which creativity is encouraged and rewarded.

Video games do allow other players to rate another person’s creativity, for example giving five stars to another player’s custom level. But those decisions are made totally outside of gameplay. In the aforementioned board games, the other players’ decisions are gameplay decisions: they have an impact on victory or defeat.

Video games have other players too. Of course, I am not talking about 12 year-old rage-quitting Counter-Strikers. But with the current trend of social networks and asynchronous games, multiplayer is more and more about taking time to play with people you know and like. Could we follow in the footsteps of board games?

Actually, we already do. The very popular Draw Something (OMGPOP) is obviously inspired by the timeless classic Pictionary (Rob Angel). Drawception (Nihildom) uses the same principles as the traditional game of Paper Telephone. A few MMOs allow rating other players’ creations to determine their popularity score, such as Mamba Nation (Mimesis Republic).

I believe this trend is very interesting and makes a lot of sense for social games, as do many ideas coming from the world of non-video games. It is up to us to hear what they have to teach.

As this article nears its conclusion, I realize I cannot conclude this article without mentioning two of the greatest video games ever for creative players.

Written to Life

When Mark Twain came home after visiting 5th Cell, he came up with his most famous sentence: “they did not know it was impossible, so they did it!” [5]

The Scribblenauts games allow the player to just type the name of items to make them appear: you thus may spawn a “blue platypus”, equip it with a “diving mask” and then throw it into a “tiny black hole”. The game recognizes tens of thousands of words, which is pretty amazing in itself. A creative player does not even need any level to have fun: I have spent countless hours on the main menu just trying things out.

If I remember correctly, my first true experiment aimed to discover how many crocodiles were necessary to kill God, but I got bored before I found out. God kicks massive ass.

There are roughly two types of levels in Scribblenauts. Firstly, those in which the player must go from A to B. Reaching the exit may get quite boring as the player ends up applying the same solutions, which is a pity; but with the ability to spawn an infinite number of helicopters and giant squids, creativity is not really necessary to overcome any obstacle.

The other type of level can get very creative. These ask the player to write relevant items or creatures into the level. The notion of relevance here depends on a brilliant lexical fields system: each item is tagged with several themes, categories, species, physical properties and so on. That’s how, when a level asked me props for a horror movie, I was able for the first time in my life to complete a video game challenge using a dead horse. What a delight!The Scribblenauts games have their flaws but they are certainly unique, and give the players many occasions to be creative: a huge number of options from many accessible grammars (from everyday life to cultural icons such as the Great Old One, Cthulhu), an immense number of choices, various situations susceptible to trigger inspiration and a never-seen-before pleasure of guessing the myriad of options the developers stuffed the code with.

One More Obsidian Block and I Quit!

Finally, I have to mention the game that already gave millions players from the whole world the craziest ideas… Ladies and Gentlemen, let us discuss, review, and praise Minecraft (Mojang).

Minecraft obviously qualifies as creative gameplay. Many players have spent hundreds of hours digging mines, designing automated rail tracks and building rainbow-colored cathedrals in this amazingly compelling construction game. The game world is very hostile, yet very simple to alter. In a few clicks, players may move mountains, build castles, and excavate dungeons.

Minecraft: changing the world has never been so easy.

Minecraft never tells the players what to do. They do not have a story objective, whether short-term or long term. How come Minecraft is not a mere level editor?

Well, the game plays with our most instinctive urges in a very clever way. The omnipresent hostility gives players an objective: survival. They are always no more than minutes away from nightfall and the horrors it spawns. If they want to survive, they need to find a shelter. This urge to find a safe place has been important to mankind ever since wild things realized we were mouthwatering. Architecture has bloomed into an amazing art form, but it all started as just an attempt to get away from dangerous beasts (including other homo sapiens).

So the game has a very strong objective. Players have many ways to stay alive: big strong walls, armors, weapons, traps… hence a large array of creative strategies. Crafting these tools requires raw material so the players have to explore the world. This exploration leads to encounters, discoveries and… ideas. Minecraft has a tremendous potential for opportunity creativity, but its world being very static (apart from systemic or random events such as trees

growing or monsters wandering), it allows for long-term creativity just as well.

The gameplay and the game world share a common grammar, mixing unique memorable creatures (especially the creepers), very simplified real-world mechanics (sand is “cooked” to make glass) and classic fictional elements (zombies are tough and slow).

The simplicity and clarity of the game semantics allow players to keep thinking about the game even after they stop playing [6].

I suspect many other things are at work to make this game a wonderful creativity enhancer: the mindlessness of block-piling [7], the regions’ consistency ensured by the biome system, the absence of a clear goal pushing players to find a meaning to their adventures beyond survival… Minecraft would deserve an entire feature. One thing is for sure: it makes gameplay and creativity a happy couple.

Summary

We have discussed how creativity is the way we combine old ideas to create new ones. Inspiration is the process of generating those ideas but creativity goes beyond ideas: it is a problem-solving ability and requires a large number of possible choices.

On the other hand, we have established that gameplay requires that the players take action to overcome obstacles and reach an objective.

We must remember that computers are unable to identify creativity. We can only give the player room for creativity and try to stimulate it, but it cannot be rushed.

Gameplay can leave a lot of room for several aspects of creativity, just not in the games you would expect at first.

There’s no arguing level makers and modders are a creative bunch. Kudos to them! But while they build stuff for the community, they temporarily step out of the realm of gameplay.

Customization usually has no impact on gameplay. When it has, conflicts may emerge between the player’s creative motivations and the gameplay objective.

As creativity is a tool, not an end, its most efficient application is in complex problem solving, strategy, tactics or open-ended systems. This requires solid, consistent and deep gameplay systems.

Here is an overview of the eight forms of creative gameplay we’ve identified here [8]:

1.In-game character editors sometimes give players a lot of deep and combinable options to determine their character’s abilities or play style.

Example: Spore

2.Complex puzzles sometimes ask players to find and apply new solutions to a given problem.

Example: Armadillo Run

3.Some deep games reward clever strategies or tactics.

Example: Total Annihilation

4.In open-ended games, players may elaborate their own objectives.

Example: The Sims

5.Games with a lot of dynamic systems, especially sandboxes, are perfect for opportunity creativity.

Example: GTA

6.Complex and consistent game systems allow players to use emergent gameplay features to their advantage.

Example: Deus Ex

7.Successfully guessing how the game will react is extremely rewarding.

Example: Scribblenauts

8.Though this is rarely done in video games, victory may depend on other players’ judgment.

Example: Dixit

Closing Comments

Why does creativity matter? As a human ability, it is a gift, intrinsically part of our nature. This skill may benefit everyone, and it may be encouraged, trained, challenged… I may be biased on the matter, but I think games are the best medium for that.

I am not only talking about serious games here [9]. But as Raph Koster advocates in A Theory of Fun, games are all about learning. Creative gameplay is good for you.The current trend of connected media is all about empowering users: social networks allow them to share information about their own lives, level editors give them the ability to tailor their experiences to match their idiosyncrasies, and the increasing success of mobile devices means electronic entertainment is available everywhere at any time.

For players, creativity can make all the difference between mindless button-mashing and unique insightful experiences. Allowing players to get creative may expend your game’s lifespan and increase its virality: playing Armadillo Run during lunch breaks taught me how open-ended gameplay makes people stop behind the player to give advice. These people end up buying the game to try their own solution.

By tackling the very subtle matter of creativity, we may also learn how to deal with other subjective issues, such as moral choices. When gameplay uses the same grammar as the game world, then choices made by the player may have deep, emergent, and meaningful consequences.

Thanks!