角色和世界创造:分析日式游戏的优势(下)

作者:Zack Wood

我很快就发现,其他日本的开发者和玩家通常也是这么使用这个术语的。但是,我很好奇,游戏有一个好世界观(游戏邦注:在日语中的发音为sekaikan,就是世界观的意思)意味着什么?通过采访、研究和个人经验,我终于想出这个术语的定义了,可以分成两个部分:(请点击此处阅读本文上篇)

1、“世界观”可以指游戏世界中存在的感情基调,这是玩家看不到的。这类似于角色的“存在感”(sonzaikan)。具有良好的世界观的游戏世界是生动而逼真的,即使它并不是对现实的准确模仿。

2、有时候,人们也使用“世界观”来指创作者对游戏世界的看法,这可以通过游戏的视觉设计、规则、操作、剧情等方面体现出来。它是游戏世界的整体“感觉”,是由所有这些元素的交互作用产生的。

所以,有一个好世界观就是指,第一眼看上去,游戏让人觉得真实,但第二眼看上去,也是有趣而精致的。通常这意味着玩家会希望重访游戏世界,无论是通过重玩游戏还是玩该系列的其他游戏或观看其他媒体。

欧美游戏中的世界观

考虑到“世界观”在日本游戏中如此广泛地使用,而欧美游戏中却极少提及“世界观”,这不免让人惊讶。我在网上很少找到与之有关的材料。

在《Anime Creativity》中,Ian Condry解释了世界观及其在动画创作中的作用,多少让我看到了它对于电子游戏的重要性。

他叙述了自己听取一个动画系列《发条武士》的制作团队的讨论。他注意到,开发者们并没有把动画当成故事——这是许多玩家和评论者的看法,而是使用“背景+世界观+角色”的模型。如Condry解释的:

“在动画制作中,比剧情更居核心地位的是角色设计、与角色有关的戏剧性背景以及定义角色所在世界的属性。角色、背景和世界观的组合通常优先于剧情编写。”

Condry继续提到游戏也可以利用相似的模型,不过他并没有详细说明那种模型是怎么样的。他的研究表明世界观在流行文化如动画和电子游戏开发中具有关键作用。世界观是开发过程的第一步,是二级元素如剧情和画面的基础。

另外,尽管Kelly从来没有在《What Games Are》使用到“世界观”这个词,但他强调的要点类似于日本的开发者头脑中的“世界观”。首先,他在《Numina》一文中基本上定义了“世界观”:

“相比于屏幕上显示的东西,事实上我们通常从游戏体验中能推导更多东西。我们可以把游戏作为想象的跳板,据此猜想人格特征、角色、行为和游戏世界的整体感觉,这些甚至超过开发者所设计的。我们的认知跳跃了,观察和关联分析不能产生移情共感,所以我们所感觉到的东西超过眼睛所看到的。”

在另一篇标题为《Worldmakers》的文章中,他指出游戏开发者就是“Worldmakers”(世界构建者),并且强调“游戏设计的艺术基本上体现在世界构建上”。对此,他解释道:

“构建世界是一个复杂的任务,需要的不只是想象力,还要考虑美感、形式和方向……不只是地形或艺术风格,并且与剧情没什么关系。构建世界是平衡动态、音画和变化节奏的元素,从而创造一种沉浸感。

世界构建是创造信服感的艺术……我的书描述了游戏是世界构建的艺术,因为我认为世界就是真正的游戏艺术所在。”

我认为,这听起来类似于日本游戏中强调的构建“世界观”。Kelly是我知道的唯一一个利用同时适用于欧美游戏和日本游戏、FPS和RPG、《模拟人生》和《满月》的游戏理论来说明和解释游戏乐趣的西方人。

在星华大学学习游戏设计

最后,我想分享一下我在京都星华大学的老师Kenichi Nishi的游戏设计课上学习到的一些实用的知识。

每个学生都想一个自己的创意,然后由老师指导我们设计游戏的主题,如“强大”或“友谊”等。一开始,我认为这么概括整个游戏太可笑了,但很快我就意识到,简单地归纳“世界观”其实有助于保证游戏的结构和一致性。他以《Katamari Damacy》为例,说该游戏的基本主题是“强大”,从剧情、画面和玩法上可以看出来。

与此同时,Nishi鼓励我们从各个角度思考我们的游戏的世界:政治系统是怎么样的?气候条件如何?能量来源是什么?人们的着装风格呢?等等。即使这些问题与玩法无关并且没有出现在游戏中。

此外,他鼓励我们仔细考虑游戏世界中应该加入的物品中。在某堂课上,我们讨论了一名学生的创意,那是关于一个能飞的可爱角色一边避开眼罩障碍一边收集心的游戏。当Nishi提问为什么是眼罩时,学生答不上来。他说,眼罩改变了一切——引入晚上戴眼罩的人,以增加整个世界的关联性。

他要强调的是,各个对象都会改变玩家对游戏世界的理解和反应,所以只是因为从现实角度觉得合理或者其他游戏也这么做,就草率地加入某些东西是很危险的。各个元素都要契合你的游戏的“世界观”,这样你的世界才能让人觉得真实合理。

具体案例:《Cafe Murder》

尽管我使用了如“日式角色”和“日式游戏开发方法”等短语,我并不是说这些东西基本上就是日本人的专属或在日本以外的地方就看不到。相反地,我认为日本人只是发展了这些技法,世界上的所有人都可以学习和使用它们。

事实上,作为尚未发布的iOS游戏《Cafe Murder》的美工和设计师,去年我就已经尝试把这些概念运用于开发实践。

12个独特的顾客

《Cafe Murder》是一个Kickstarter的融资项目,是关于某咖啡厅厨师谋杀顾客的游戏。我根据能定义外貌、行为的简单概念,设计了12个顾客角色,类似于Condry所说的“Dekoboko and Friends”。视觉画面上,我尝试丰富各个角色的颜色,使之容易辨认、能够以符合他们的个性和概念的方式表达他们的情绪。

例如Frantic Fred,他是一个“忙碌”的人,一个挑剔服务的匆忙商人。Sharkeeta是一个富有的胖鉴赏家,非常好吃。Pincushion与其他角色不同,他是一个爱打洞的朋克仔。

(Frantic Fred、Sharkeeta和Pincushion)

我还尝试尽量减少当面对话,同时添加顾客的反馈菜单——当玩家有空闲时,如果想了解各个顾客的个性时可以看。

《Cafe Murder》的世界观

在京都星华大学时,我在游戏设计课上就开始设计《Cafe Murder》了。在那时,我选择的主题是“服务和保护”。尽管基本的游戏玩法是快速选择材料、制作三明、上单,这要求玩家理解和迎合各个顾客的个性,以提高效率和顾客满意度。

例如,玩家最好先给Fred送上还没做好的三明治,因为他个性急,多花时间给Sharkeeta准备她的三明治的时间,因为她的小费很大方,这样都可以避免他们暴跳如雷。

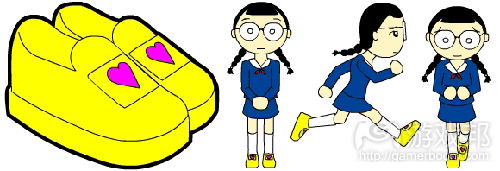

在与世界观有关的具体,我尤其在间一点。当给女服务生Rainy设计“加速鞋”时,我原本在鞋子上画了一个类似于赫尔墨斯的翅膀的东西,但我很快发现,那样看起来太奇幻了,会令人想起《Kid Icarus》那样的动作游戏。

在《Cafe Murder》的世界中出现带翅膀的加速鞋是不合适的,而带心形的可爱加速鞋就合理多了。我意识到《Cafe Murder》的世界是一个关心顾客比魔法翅膀更重要的地方。如果你亲自证实一下,那就去苹果应用商店下载《Cafe Murder》吧。

结论

就设计角色和使用世界观而言,我看到了日本游戏设计中的核心:简化和风格化可以用于创造真实感和增加拓展性。

就个性和外观上,日式角色是简单而夸张的,表现力强且容易理解;游戏世界围绕简单的概念来构建;应该慎重地选择出现在世界中的物品。

然而,这些方法更多地是为了创造一种感觉而不是愉悦视觉;角色要让人觉得可爱而真实,热门角色的号召力是无穷的。类似地,游戏的世界要让人觉得逼真,这样玩家才会想在不同的媒体中重复欣赏它。

但愿我已经把我在日本学到的东西讲清楚了。感谢阅读!(本文为游戏邦/gamerboom.com编译,拒绝任何不保留版权的转载,如需转载请联系:游戏邦)

Characters and Worldbuilding: Analyzing the Strength of Japanese Games

by Zack Wood

I soon discovered that other developers and gamers in Japan often use the term in similar ways. But, I wondered, what does it mean for a game to have a good sekaikan? Through interviews, research, and my personal experiences, I have developed a definition of the term, which can be broken down into two parts:

First, sekaikan can refer to the feeling that a world exists beyond what you see onscreen. This is similar to characters’ sonzaikan; the world feels alive and real, even though it may not be a physically accurate simulation of reality.

At other times, people use sekaikan to refer to the creator’s vision for the game’s world, which informs everything from the visual design, to the rules, to the controls, to the story. It is the overall “feel” of the world, created by the interaction of all these elements.

Having a good sekaikan, then, means that the game feels real in the first sense, but is also interesting and well-done in the second sense. Often this means that the player wants to re-visit the world, whether through replaying the game, playing other games in the series, or through other media.

Sekaikan in the Western World

Given its frequent use in Japan, there is surprisingly little discussion of sekaikan in the English-speaking world. I found only a few mentions of it on the internet, here and here.

In Anime Creativity, however, Ian Condry touches on sekaikan and its role in the creation of anime, which sheds some light on its importance in video games.

He describes what it was like to sit in on discussions among the production team of an anime series called Zenmai Zamurai. What he noticed was that, rather than thinking about the anime in terms of the story — which is the focus for many fans and reviewers — the developers used a “premise + worldview + characters” model. As Condry explains:

More central than the story itself in organizing the collaborative production of anime was… the design of characters, the establishment of dramatic premises that link the characters, and the properties that define the world in which the characters interact. This combination of characters (kyarakutaa), premises (settei), and world-settings (sekaikan) generally came prior to the writing of the story.

Condry goes on to mention that a similar model could be used for games, and although he doesn’t specify what that might be, his research shows the crucial role of sekaikan in the development of popular culture like anime and video games. It is established in the beginning of the process, and it informs secondary elements like the story and visuals.

In addition, although Kelly never uses the term sekaikan on What Games Are, he emphasizes points similar to those that Japanese developers consider when addressing sekaikan. First, he essentially offers a definition of sekaikan in his post titled Numina:

We often infer more from a game experience than is actually on the screen. We have the capacity to use the game as an imaginative springboard, inferring personality traits, characters, behaviors and a sense of a larger game world beyond even what the developer intended. We make cognitive leaps, little observations and associations that contain the quality of empathy, and so it feels like there is more there than meets the eye.

In another post entitled Worldmakers, he goes on to insist that game developers are “worldmakers,” and that “the art of game design is all about the place,” explaining that:

Creating a world is a complex task that demands not just imagination, but elegance, form and direction… It is not just geography or art style, and it has very little to do with story. It’s a balance of dynamic, audio-visual and pace-changing elements all intended to achieve a kind of engagement.

Worldmaking is the act of creating a canvass… Much of my book talks about the art of games as worldmaking because I believe that worlds are where the true art of games lies.

To me, this sounds similar to the focus in Japan on the world experienced through a game. Kelly is the only person I am aware of in the Western world with a theory of games that takes this into account and explains the fun of games in a way that applies to both Western and Japanese games, FPSs and RPGs, The Sims and Harvest Moon.

Game Design at Seika

Finally, I wanted to share some practical lessons that I learned in Kenichi Nishi’s game design class at Kyoto Seika University.

As each student came up with their own idea, he instructed us to assign a theme to our game, such as “getting bigger” or “becoming friends.” At first, I thought it was ridiculous to summarize an entire game in such a way, but I soon realized that, as a simple expression of your “worldview,” it can actually help provide the game with structure and consistency. He said that in Katamari Damacy, for example, the basic theme would be “getting bigger,” which is reflected in the story, visuals, and gameplay.

At the same time, Nishi encouraged us to consider the world in our game from all angles: What is the political system? What is the weather like? What is the source of energy? What types of clothes do people wear? And so on, even if the element in question doesn’t have anything to do with gameplay and won’t appear in the game.

In this vein, he encouraged us to think carefully about what items we would include in the game’s world. In one class, we discussed a student’s idea for a game about a cute character that flies through the sky, collecting hearts while avoiding obstacles like eye masks. When Nishi questioned her inclusion of eye masks, however, she didn’t have an explanation. Eye masks, he said, changed everything — they bring in the existence of human beings who wear eye masks at night, adding a whole world of associations.

His point was that each object changes the user’s understanding of and response to the game’s world, and so it is dangerous to thoughtlessly include something just because it would make sense in reality or because other games have done the same thing. Each element must fit with your game’s sekaikan in order for the world to feel real and make sense on its own terms.

A Concrete Example: Cafe Murder

Though I have been using phrases like “Japanese characters” and “the Japanese approach to video game development,” I don’t want to imply that these things are fundamentally Japanese or inaccessible to people outside Japan. On the contrary, I think that while Japan has developed these techniques and approaches, anyone in the world can learn from and utilize them.

In fact, as artist and designer for an upcoming iOS game called Cafe Murder, I have had the chance to try to put these concepts into practice over the course of the past year.

Twelve Unique Customers

Cafe Murder, which began as a Kickstarter project, is a restaurant simulation game with a chef who attacks the customers. I built each of the twelve customer characters around a simple concept that defines their appearance and how they behave, similar to what Condry described with “Dekoboko and Friends.” Visually, I tried to make each character colorful and easily recognizable, expressing their emotions in a way that suits their personality and concept.

Frantic Fred, for example, is the “busy” one, a rushed businessman who has to be served right away. Sharkeeta, the wealthy and corpulent connoisseur, represents gluttony, and Pincushion, unlike all the others, will both survive and enjoy a stabbing.

Frantic Fred, Sharkeeta, and Pincushion

I also tried to keep in-your-face dialogue to a minimum, while adding a customer feedback menu that can be viewed at the player’s leisure if they choose to read through and learn about each customer’s personality.

Sekaikan, Cafe Murder-style

I started designing Cafe Murder in the game design class at Kyoto Seika, and at that time I chose the theme “to serve and protect.” Although the basic gameplay revolves around using quick reflexes to catch ingredients and assemble sandwiches, getting good at the game requires understanding and catering to each character’s individual behavior in order to serve sandwiches with maximum efficiency and satisfaction.

Knowing, for example, that you should serve that imperfect sandwich to Fred before he gets too impatient, whereas it is worth taking longer to get Sharkeeta’s sandwich just right because of her generous tips — all while protecting them from the insane chef’s rampages.

In terms of concrete design decisions related to sekaikan, I remember one in particular. When designing the “Speed Shoes” upgrade for Rainy the waitress, I originally began drawing sneakers with Hermes-looking wings on them; I soon realized, however, that this felt too mythological, reminiscent of an action platformer like Kid Icarus.

It didn’t feel right to have speedy wing shoes in the world of Cafe Murder, whereas cute, speed-boosting hearts made a lot more sense. Cafe Murder, I realized, is a place where loving care for customers is more powerful than magical wings. If you’d like to check it out for yourself, Cafe Murder is free to download in the App Store.

In Conclusion…

In terms of both the approach to characters and the use of sekaikan, I see one overarching theme in Japanese game design: simplification and stylization as a means of creating a sense of reality and expansiveness.

The characters, both in terms of personality and appearance, are simplified and exaggerated, expressive and easy-to-understand. Game-worlds are organized around simple concepts, and items in the world are chosen or rejected with great care.

The effect of these measures, however, is to create the feeling that there is more than meets the eye; characters feel endearing and real, and popular ones are consumed almost endlessly. Similarly, the worlds in games feel alive, and players want to visit them again and again through different media.

I hope I have been able to convey clearly what I learned during my years in Japan. Thank you for reading, and please let me know if you have any comments, criticisms, or insights about the ideas I presented here.

You can read more analysis from Zack at his blog, and also check out Beaver Toad Software — the official site for the team behind Cafe Murder.(source:gamasutra)

闽公网安备35020302001549号

闽公网安备35020302001549号