对于游戏开发者来说自信到底是利还是弊?

作者:Matt Waldron

上周我参加了在波士顿的Massachusetts Convention Center举办的PAX展会。而我作为一名作曲家兼写手,为了能在游戏产业中获得一定的发展,我便投入大量的时间参加各种研讨会,以学习各种专业知识。作为一名音乐人,我在年轻的时候总是会定期参加NEMO会议(游戏邦注:每年在波士顿地区召开),所以我很肯定这些研讨会对于鼓舞士气的重要性。所以在我频繁参加了各种研讨会(有好有坏)后,我得到了两个重要的结论:(1)每个讨论小组成员(至少他们的观点都具有可取性)都充满自信(或者至少表现出自信),深切肯定了自己对于这个产业的了解;(2)任何握着假文凭的人也能够轻松成为研讨会小组的一员,并且他们所提出的一般意见也都会得到重视,也没有人会提出疑问。

这些研讨会小组成员会说“我们有请‘Fake Games, Inc.’总裁兼创始人XXX向各位传授如何进入游戏产业。”而此时演讲者就会告诉人们“离开这里,开始积极地创造你的游戏”并“始终致力于创造并思考你的游戏”,而“如果我发现简历中出现排版错误的情况,我便会毫不犹豫地将其丢弃。所以请确保你的简历绝对准确。”之后学演讲者会让人们向其提出问题,而他也将即兴地阐述一些内容,然后他会递交自己的名片,并与参加者握手表示感谢!

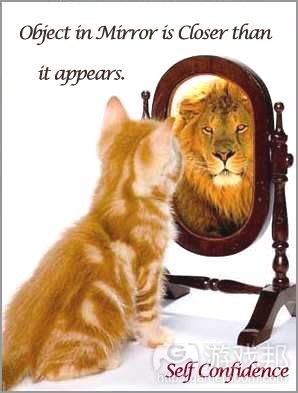

我们总是会不经意地相信那些自信地表达自我想法的人。自信之所以会等同于实力,是因为我们常将自信作为判断一个人所言是否与其所行相符(或者只会吹牛)的一种辅助手段。在商务领域中,那些过度自信并将这种趋势扩散至整个社会中的人士并非由内而外散发出这种自信。相反地,这些人大多都是因为有钱,有关系,或者擅于伪装自己而呈现出这种自信。而因为游戏产业比起“西装革履”领域,我们更重视创造性和娱乐性,所以上述所提到的这种趋势在这里并不明显——不过也并非完全不存在。而这种不幸的现实更是不利于那些投身于游戏创意层面的开发者,优秀的艺术工作者一般也总是那些直面现实,并且容易对自我和自己的作品产生怀疑的群体。

可取的自信 vs 不可取的自信

自信应该是:你投入了大量的时间精通了一种技能,从而推动你能够使用这种技能而更有效力地完成任务,直至这种技能成为你的第二天性。所以这时候当你自信地向别人展示这一技能时,并不是因为你想这么做,你只是在诚实地表达自己的能力而已,因为你真的非常能干。然而在现实中,这种形式的自信却非常少见。通常情况下人们只会注意并极力效仿这种“可取”自信的特征,他们行事的主要前提就是——“如果我成功骗过了所有人,我就不需要真的会做事情”。结果,这个世界因此催生出了“不可取的自信”的多种版本,我们将其区分为多个子集,如“错误的自信”(这种人至少在心里清楚自己充满过度自信)以及“幼稚的自信”(这种人总是天真地认为自己非常出色,并且也尽力去伪装自己,不过现实却往往与之相反)。

遗憾的是,不可取的自信将会引导着人们走向生活中的误区,即这些人会以自己获得金钱,物质以及地位的能力作为评判价值的标准。我有一些朋友也是如此,即过度高估了自己的实践能力。我曾经听过一个备受尊敬的投资顾问(在一家全国知名的投资公司中享有非常高的地位)对于掷骰子游戏的演讲,但是当我尝试着去询问其概率时他却瞬间目瞪口呆了。当我服务于一家投资咨询公司时,我发现有些律师们总是会曲解法律条款,而持有数十亿避险基金的管理者也会犯一些让中学生耻笑的错误。我想只要一个人不至于太愚蠢,都有可能挖掘出内心“不可取的自信”而利用它去谋取利益。

创意和自信:难以共存

就如上述所提到的,真正的自信是源于对一种技能的精通;并且作为一种目的而非手段,我们能够基于一定标准轻松且客观地做出衡量。举个例子来说,一个服务员能够通过几次的实践学会平衡托盘与餐具的重量,从而在执行送餐任务时表现出真正的自信(游戏邦注:我们可以通过他多久摔碎一次餐具去评判这种自信)。而对于艺术创造则不存在明确的“好”与“坏”;尽管我们尝试着去找出合理的衡量标准,但却始终未找到最适合的限度。如此也就是,你永远不可能写出一首完美的音乐,创造出一个完美的角色,设计一幅完美的图像,因为在你前面总是停留着一块等待完善的空间。所以在艺术领域中,我们总是很难找到真正的自信。

任何一名优秀的艺术家都是经过不断的自我批评才磨练出现在的品质。所以应该是一开始便拥有自我意识的心态才推动着这些艺术家成为真正的艺术家。作为作曲家的我也是如此,从来不会对自己的作品感到完全的满意——部分原因是我从不会从竞争角度去评判我的音乐质量,而是基于一个绝对的标准做出判断,也就是任何一首音乐的质量是来自于内在及其应用。并且我敢保证,这种心态适用于所有媒体的艺术家。有时候我也会去回顾我在几年前所创作的音乐,从而让我能在多年后再次发觉到这是一首具有出色想法的优秀曲子;但是在当时的创作过程中我的心态却是:如何做才能变得更好?如何做才是更加有效?通常来说这也是大多数艺术家所具有的共同想法;而也正是因为抱有这种想法才导致了一个严重问题的出现,即艺术家的自信遭到了极度的遏制。

困境

这对于那些想要在游戏产业谋得一份职业的艺术家来说便是一个巨大的矛盾:因为一般来说那些负责招聘的人员总是希望在应聘者中看到自信。而艺术家却因为知晓自己的作品不管多么优秀都存在着不足而始终缺乏自信。如果艺术家的身上开始出现不可取的自信感,那就等于为他自己的作品敲响了丧钟:当他们开始对自己的作品产生信心的时候,他们便开始趋于满足,并不再追求进一步的完善。你唯一需要表现出这种自信感的时机只有在面试的时候。但是难道唯一的解决方法便是在这种情况下违背自己内心的真实想法而虚造自信?这是我在这个产业中屡试不爽的一种方法,因为这种欺骗行为并不会导致任何实质上的影响。游戏产业总是很难有效地结合艺术与商业——游戏是各种不同艺术家和个体注重商业元素而协作完成的产物。之前我总是欺骗自己能够创造出一些优秀的作品,但是后来我发现我的这种想法将对别人倾注了时间和努力的艺术品造成消极的影响。

作为一个项目的作曲者,如果有人问我“你是否有创作高科技舞曲的经验?”那么我将会有两种回答。一种是“是的!(问话者一般不会去证实我的答案或者他不一定具有足够敏锐的音乐素养以判别我的能力)我非常了解并且喜欢高科技舞曲的节拍和音律,在创作这类型舞曲时我们需要在EQ中添加超低音频或者将低音率设置为60赫兹(我只是在随便扯一些无意义的术语,并且我知道问话者不会对此探究根底,他只会想着“这人真是专业人士啊”)。”另外一种回答则是完全诚实的回答,也就是“我了解高科技舞曲,但是我却没有创作这类型音乐的经验,可以说这并不是我的强项。”如此看来第一种回答更能够帮助我通过面试;但是第二种回答则深刻考虑到我自己对于整个创造性工作的影响,顾及到其他艺术家也将在此倾注自己的努力,并且能够推动我与其他人进行更紧密的协作而创造出真正优秀的作品。如果该公司真的希望应聘一名擅长创作高科技舞曲的作曲者,并且他们也愿意雇佣我,我便会投入百分百的努力于工作中。而如果该公司选择的是一名擅长制作高科技舞曲的人,也就说明他们愿意雇佣一名能力不如我的人只是因为他选择了第一种回答。

其实我对于这一困境的定位还很含糊,老实说,是我的道德指南指引着我这么做的。有时候道德指南真的非常有效,但是有时候当我面对着结果时我也会感到疑惑。而作为游戏产业中的一名艺术家,我总是不断地思考着一系列问题,如优秀的艺术技巧和自信是否能够共存?自信是否真的会阻碍艺术发展?艺术家为了获得工作是应该假装自信还是考虑同项目其他艺术家的立场而坦诚相对?不论何时,艺术家是否都需要保持诚实?

(本文为游戏邦/gamerboom.com编译,拒绝任何不保留版权的转载,如需转载请联系:游戏邦)

Confidence: Virtue or Vice for Game Designers?

by Matt Waldron

Introduction

This past weekend I attended the PAX East showcase at the Massachusetts Convention Center in Boston. While the majority of attendees were there to have fun, hang out with like-minded gamers, and check out some of the newest games on or coming to the market, I, as a composer and writer looking to make headway in the game industry, spent the vast majority of my time darting from panel to panel to learn as much as I could. Being a musician, I used to regularly attend the NEMO conference (held annually in the Boston area) in my youth, so I was under no illusion about how much value those panels actually tend to wind up yielding. As I attended panel after panel—some good, some bad—I was struck most by two overarching observations: (1) that every panelist (that is, at least every panelist worth listening too) brimmed with confidence (or at least appeared to brim with confidence) that he or she had everything there was to know about the industry figured out; and (2) that it would have been a piece of cake for me to serve on one of those panels with some fake credentials and spout generic advice that would have been taken seriously and never questioned.

“We have Matthew Waldron, president and founder of Fake Games, Inc., here to speak to you about how to get into the game industry,” they would have said. I would have proceeded to tell everyone to “get out there and take the initiative to make a game” and to “persevere by working on and thinking about games all the time” and that “if I see a typo on a resume I just throw it in the trash, so make sure your resume is perfectly clean.” They would have eaten it up. I would have had people ask me questions afterwards, I would have made something up off the top of my head, and soon enough I’d be getting a business card and a hand shake and a “thank you so much for your insights!”

It is astonishingly easy to unwittingly give credence to someone who presents himself or herself confidently. The assumption that confidence equals clout is used all too often as a substitute for making a thoughtful and educated assessment of what someone has said and deciding if he or she is someone who actually knows what he or she is talking about, or if he or she is simply good at BS-ing (the latter makes up the vast majority of people involved in almost any industry in my experience). In the business world, it is nearly universally true that those who consistently present with that awful ubiquitous, arrogant confidence that pervades our society have no right to be so high on themselves. Chances are those people got where they are because of money, connections, or a talent for shoveling BS (which they shoveled at an HR representative, himself a BS-er, who ate it up). Because the game industry is by nature more focused on creative products and entertainment than are the ‘suit and tie’ businesses, the aforementioned trend is certainly less prevalent—but it is far from absent. And this unfortunate reality creates a very difficult situation for those involved in the creative aspects of games, because good artists tend to be those people who are in touch enough with reality to have doubts about themselves and their work.

Distinguishing Legitimate Confidence from Illegitimate Confidence

Here is what confidence really ought to be: you work hard to develop a skill for a long time, and eventually become so effective with that skill that your ability to employ it with effectiveness and consistency becomes second nature. As a result, you present to others as confident with respect to that skill, not because you’re trying to present confidently, but simply because you’re presenting yourself honestly, and in truth you are extremely capable. However, confidence in this form exists quite sparsely in reality. More often than not, people observe the characteristics of those ‘legitimately confident’ individuals and mimic them on a premise that roughly equates to ‘if I can successfully fool everyone, I won’t have to put in the work’. As a result the world winds up with multiple variations on ‘illegitimate confidence’ that one could codify and classify into subgenres such as ‘false confidence’ (which relates to a person who at least knows deep down that he is full of it) and ‘naive confidence’ (which relates to a person who has actually convinced himself that he is as great as he presents to be, despite overwhelming evidence to the contrary).

It is a sad fact that being illegitimately confident will generally get one quite far in life, at least insomuch as one measures one’s worth by his ability to obtain money, materials and status. I have several friends who think far more highly of their abilities than is deserved who have done tremendously well in business. I’ve listened as a well-esteemed investment adviser in a lofty position at a nationally recognized investment firm gave me a lecture on how Craps is a game of hot and cold streaks (he stared at me dumbfounded as I tried in vain to explain how probability actually works). When I worked at an investment advisory compliance firm, I watched lawyers misinterpret the law for what I could best classify as an inability to read, while billion dollar hedge fund managers sent communications that would make a middle school student blush. As long as a person can be just a hair smarter than completely stupid, he’ll do just fine making money with a little bit of illegitimate confidence in his corner.

Creativity and Confidence: Rare Cohabitants

True confidence, as described above—the natural offspring of the mastery of a skill; an ends and never a means—manifests readily with respect to perfunctory or otherwise easily-definable skills the quality of which can be objectively measured with ease. For example, a waiter will eventually get very good at balancing a trays worth of dishware with a little practice, and so will eventually exhibit confidence in carrying out this task (we can measure the appropriateness of this confidence by how often he shatters a tray’s worth of dishware). With respect to creative arts, however, there is no easily definable ‘good’ or ‘bad’, and even when we do manage to figure out some of the criteria for measuring quality, there is no hard ceiling to define perfection, viz., you’ll never write a perfect piece of music, create a perfect character, design the perfect graphic—there is always room for improvement in the arts. Therefore, in many respects it is extremely difficult to ever be confident when it comes to artistic endeavors.

Every good artist I know became good by being extremely self-critical. In fact, it is probably that mentality of self-awareness that drives artists (in the true sense of the word) to become artists in the first place. As a composer I am never fully satisfied with anything I write, and very rarely am I satisfied at all—in part because I judge the quality of music not relative to competition but on an absolute basis; the quality of a piece is intrinsic to the piece and its application. I am certain this mentality is the same for artists in every other medium as well. Sometimes I can listen to something I wrote years ago that I have long since left behind and discover that it was a pretty solid piece with some cool concepts behind it; but during the creation process my mentality is always: how can this be better? how can this be more effective?. Aside from a few outliers, this is the way artists think; and it this way of thinking that creates a serious problem when it comes to being confident about one’s art.

The Dilemma

Here is the conflict for artists looking for work in the game industry: people in charge of hiring, generally speaking, want to see someone who is confident in his work. Artist are generally, by nature, not confident in their work because they are aware that their work, no matter how good it is, could be so much better. Adopting a significant illegitimate confidence as an artist is pretty much the death knell for one’s craft: the moment one becomes confident in his art he also become content, and contentment pretty much ends the quest for improvement. Yet often times presenting with that air of confidence is the only way to get hired. So is the solution to fake confidence in those situations and just know the truth yourself? That’s certainly what I have done in the business world many times over, because there is really nothing of substance being affected by such deception. But the game industry is a difficult mix between art and business—a game is a collective work that comes together through the collaboration of many different artists and many individuals focusing on the business aspects as well. I personally have a very hard time being deceptive about what I can bring to the table when I know that I could have a negative impact on a piece of art that so many other people have invested their time and effort in.

If I’m being considered as a composer for a project and I’m asked ‘are you experience in writing techno?’ there are two replies I could give. One is ‘Yes! [it's not like the interviewer can prove otherwise or has the musical acuity to determine otherwise] I have a library of beats and sounds I like for techno [lie: I'll just yank a few out of a program on the spot] and for production you just concentrate a lot on panning and make sure to add a sub-bass and boost the bass fundamental at 60Hz in the EQ [true, but I'm just throwing out buzz words that I know the interviewer isn't going to follow so he moves on thinking 'this guy knows his stuff']‘. The other, far more honest answer is ‘I understand the principals behind techno, but I don’t have a ton of experience with it and it isn’t something I would cite as a strength’. The first answer is far more likely to get me hired than the latter; yet the latter is considerate of my effect on the overall creative work and takes into account the fact that other artists will be working hard on this game and deserve to collaborate with someone who can make the best end product. If they need someone really good at writing techno, I’m thrilled to give it my best effort if they want to hire me, but if they can find someone who is a techno wiz, that person is probably a better choice. On the other hand, they might end up hiring someone less competent than me for the job who just happened to choose option #1 from the answer choices above.

As you can tell from the equivocation in the previous paragraph, I haven’t really settled on an appropriate course with respect to this dilemma. I tend to be honest, because that is what my moral compass tells me to do. Sometimes it works out for the best, other times I look at the result and wonder if it would have served me and everyone else better had I just lied and gotten in the door. So at this point I open the debate up to the reader. Can great artistry and confidence coexist? Does confidence definitionally put an end to artistic improvement? Are there circumstances under which an artist is best to feign confidence for the sake of getting hired, or should the artist be honest in consideration of the other artists working on the project? Should an artist, nay, a person simply be honest regardless of the circumstances? These are serious philosophical questions I find myself considering quite regularly as an artist in the game industry; I’m very interested to hear what people think on this topic.(source:GAMASUTRA)