阐述《Candy Box》更具“社交性”的原因

作者:Leigh Alexander

上一周,Twitter上出现许多关于“糖果”的信息。比如“我一秒钟就败光100个棒棒糖了”、“我现在在地上扔了1000个糖果,为什么我要把这么多糖果扔地上”;回答青蛙的谜题,升级宝剑等。似乎是在玩一款Facebook游戏。

Aniwey的《Candy Box》——这股狂热的源头,并不是Facebook游戏,或者甚至不是“社交游戏”。它是一个小型、免费、用ASCII码制作、在浏览器上玩的“游戏”。它突然之间就火了。

虽然不是社交游戏,但它有一套跟玩家们嘲弄多年的社交游戏一样“空洞”的机制:你的资源随着时间积累而增加。这意味着,许多玩家会吹嘘自己在周末时在办公室的电脑上开着游戏,以得到糖果奖励。

在《Candy Box》中,当你把资源用于升级时,你必须再次等待升级系统的响应。你可以做任务,但完成这个任务后你必须等待大约两分钟,才能再做另一个任务。甚至还有货币系统(尽管与真钱无关)。

简直就像玩电子表格,但它很快就在玩家当中传播开来,特别是那些反对将强制通告和新闻垃圾邮件当作“游戏机制”的玩家。人们喜欢分享玩《Candy Box》的体验,因为这个游戏虽然没有指导或反馈这种推动游戏进展的社交元素,但出人意料地充满惊喜。

《Candy Box》的成功令人吃惊,体现在几个方面上,最主要一个是证明了它的成功并不是靠Facebook游戏的斯金纳盒式的“刷”机制,也不是靠玩家们诟病的病毒式推广,而是靠平台和表现方式。在Zynga宣布它的Facebook游戏生意持续衰退之后,《Candy Box》开始吸引玩家的关注。

关于《Candy Box》的热潮来得快,去得也快。毕竟,它的主要机制是相当简陋的,玩家可以在几天的沉迷期内就玩完它。但这款小游戏令人难忘,给我们留下几点经验。以下是最有意义的几点:

发现感

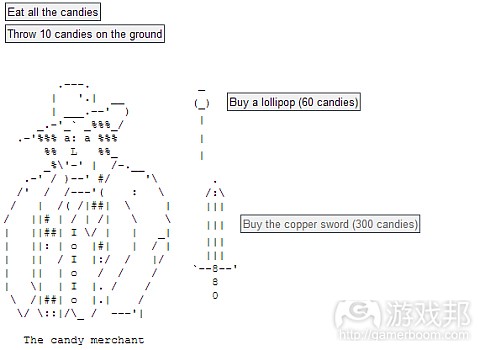

《Candy Box》的界面简单得不可思议:屏幕上只有一个“糖果商人”,其实就是用ASCII做成的一个人物图像。“糖果商人”对糖果非常迷恋,愿意用棒棒糖跟你换糖果。玩家的糖果数量会随着时间慢慢增加。

一开始,你只有两个无目的的选项:吃掉你正在收集的糖果,或者把糖果扔在地上。一般人会看着屏幕,什么也不做。游戏继续进行。

玩家的耐心和好奇心会得到奖励,这就是《Candy Box》令人惊奇的地方。经过几分钟的扔糖果或与商人互动,屏幕上会出现:一个农场,你可以种植棒棒糖,这样你就会收获更多棒棒糖。除了棒棒糖,商人的商品栏中又多了一把宝剑。再然后,屏幕上出现仓库和任务按钮。

按下任务按钮,一个简单的“世界”开启了:无成任务就会得到地图作为奖励,之后还会有更多有趣的道具、升级,如出谜题的青蛙或为棒棒糖疯狂的女巫。每一个新发现都是一个有意义的变化。之后,游戏变得更加困难,要求玩家投入更多时间。玩家迫不及待地想知道下一个稀奇古怪的东西是什么。

传统的“社交游戏”体验

除了一个FAQ提供非常常见的问题答案,这个游戏几乎没有给玩家任何指导和反馈。这种简约的风格让人回想起早期的游戏,那时候的游戏令人费解,进展游戏的唯一办法就是玩家之间分享游戏的各种秘诀和知识。

一开始,玩家根本无法想象在《Candy Box》中居然会出现“龙”。当你还在数糖果和打树桩时,Twitter上已经有人爆料自己开始种树和使用酸雨法术打败城堡中的怪物了。听起来简直不可思议,你决定一探究竟。

童年时代的玩家,总有一帮爱吹嘘的玩伴,透露他们已经在游戏中战胜了你自己不可能克服的挑战。或者你通过各种聊天和传闻知道了游戏中的秘密和惊喜,那些东西是你自己想都没想过,更别说亲自尝试。

《Candy Box》就是这样一个隐藏着许多“复活节彩蛋”般的惊喜的游戏。如果不是有人透露,你可能永远不会想到不停地点击糖果商人,他就会给你一点东西求你不要再纠缠他。玩家仍然怀念那些只能靠各种谣传和秘诀才能进展游戏的日子,而《Candy Box》似乎唤醒了那段美好记忆。

要求极低

《Candy Box》的要求低得难以置信,只占用一个浏览器标签罢了。你可以通过书签按钮保存游戏。在你用电脑工作、阅读或写邮件时,只要让游戏页面开着,你的资源就会一直积累。

游戏允许你通过投入资源加快生产速度,只要点击鼠标几下使得“让游戏开着”的行为不令人生厌。真正的游戏玩法如做任务、购买或用你的大锅(很后面才出现)准备药水和法术,也只需要几分钟的时间就操作完了,之后你只要游戏开在那里就好了。

在社交游戏中,玩家获得经验的主要途径就是花时间。大多数设计师和评论者认为Facebook的城市建造游戏要求太高、容易上瘾、费时间。而《Candy Box》却表明,这种低阻力的游戏之所以吸引人,是因为它可以作为日常消遣、只占一个浏览器标签、让它在后台默默运行就能得到奖励。

《Candy Box》从来没有强占你的注意力——没有通知、没有提示、甚至不会弹出要求玩家与好友分享游戏的窗口。相反地,正是它的这种暧昧不明使它成为一款成功而有意义的游戏,成为一伙人分享和讨论的对象。

似乎当你不强迫玩家邀请其他玩家、不试图占用玩家的时间时,玩家反而会自愿地推广游戏和投入时间。这真是不可思议的力量。

极简风格

毫无疑问,正是《Candy Box》的神秘作者、老式ASCII码图像和只使用一个窗口赢得了玩家的忠实。想像一下,如果这个游戏具有丰富的色彩、卡通自定义角色、说明文字和动画,那会怎么样呢?即使是一点点声音效果,也会使游戏体验大打折扣。

它的画面和创意都受到制约,不会干扰玩家的注意力或对设备性能有要求。玩《Candy Box》的一半乐趣是,看看它的神秘制作者利用这么简单的资源,能还整出什么花样。这种清爽、手动输入的画面和感觉似乎使游戏更有魅力,给玩家提供一种简单但不令人分心的体验。

来得快去得快

玩家对《Candy Box》的热情已经消退,它的高潮只维持了短短几天。那是因为它太容易让玩家觉得“完成了”——游戏的主要玩法只需要几天就能完成,只有最痴迷的玩家才会继续玩下去,毕竟投入相当多的精力后,玩家还是能收获一定的程度的成就感和满足感。

游戏的目的似乎不是尽可能留住玩家,而是用相当简单的机制让玩家随心所欲地玩。这简直是公然挑战社交游戏尽可能留住玩家的传统,虽然《Candy Box》的流行不能长久,但也没有被玩家谴责为浪费时间的垃圾,部分是因为虽然玩家的热情消退了,但对游戏仍然怀有敬意。

赢利策略

现在,游戏的制作者Aniwey当然可以充分利用这个好名声来开发其他项目。制作者表示续作已经在进行中,但表示希望玩家能给予资助作为对他们工作的支持,使更多这种ASCII项目得以诞生。我绝对同意我花在《Candy Box》的时间是值几块钱的;如果有成千上万的人也是这么认为的,那么制作者应该可以建立一个正式的玩家社区了。

那些看似对传统设计的“最佳实践”无兴趣或不在意的游戏,特别是在系统化和离间化的社交游戏竞技场,往往一夜之间大获成功。在《Candy Box》中,我们学习到了重要的一课——人们不一定讨厌“刷”任务似的游戏玩法、社交玩法、定时玩法或者甚至基本上只有电子表格式的图像界面的游戏。他们讨厌的是社交游戏商业强塞给他们的东西。(本文为游戏邦/gamerboom.com编译,拒绝任何不保留版权的转载,如需转载请联系:游戏邦)

Why Candy Box became more social than ‘social games’

By Leigh Alexander

Over the last week, the Twitter feeds of game creators and fans alike began to fill with a peculiar wave of notices about candy. Things like: “I’ve maxed out at 100 lollipops a second,” and “I’ve now thrown 1000 candies on the ground, why am I throwing candies on the ground,” and people answering frog riddles and upgrading their swords into better swords. It looked a lot like a Facebook game.

Except Aniwey’s Candy Box, the source of the craze, isn’t a Facebook game, or even a “social game,” per se. It’s a tiny, free, ASCII stat-based grind played in a browser tab, and for a hot second there, it was all the rage.

This in spite of the fact that it has the same kind of “empty” grind mechanics players have derided in social games for years now: Your resource counts increase simply with time spent, which means scores of people bragging about how they left the game open all weekend at the office in eagerness to return to a candy bounty.

When you spend resources on an upgrade, you have to wait to interact with the upgrade system again. You can undertake a quest, but need to wait about two minutes until you can do another. There’s even a dual currency system (though no real money is ever involved).

It’s a spreadsheet, really, a numerical climb, and yet it spread virally entirely on the volition of participants, the same kinds of players who would have opposed forced notifications and newsfeed spam as a “game mechanic.” People loved the shared experience of participating in Candy Box, and since the game’s surprisingly full of mysteries and secrets with little direction or feedback, that social component became actually-essential to progress for many.

The success of Candy Box is fascinating on several levels, the main one being that it proves that it isn’t actually the hooky, skinner box-ish grind of Facebook games nor their rampant virality that is inherently offensive to gamers, but probably the platform and the presentation instead. And the purveyors, maybe — Candy Box began burning up fan attention right after Zynga reported continued declines in its Facebook game business.

Chatter about Candy Box died down almost as quickly as it sprung up — the main game is relatively short all-told, and players can (and did) devour it in a few days of all-consuming obsession. But the little game that could is sure to be memorable, and leave lessons in its wake. Here are the things that worked best:

Sense of discovery.

Candy Box opens with an incredibly minimal interface: The ‘Candy Merchant,’ actually an ASCII graphic of the “fourth Doctor,” is on the screen. He is obsessed with candy and wants to trade you lollipops. The player’s candy count begins ticking up slowly.

At first, you have two purposeless choices: Eat the candy you’re accumulating with every second you look at the screen, or throw it on the ground. The average person could look at this screen, see nothing of import, move along.

But Candy Box is built on continually surprising players by rewarding patience and curiosity. After a few minutes of throwing candy or interacting with the merchant, more things appear: A farm where you can plant the lollipops you’ve bought, with the promise they’ll produce more lollipops. More items appear in the Candy Merchant’s menu, including a sword. And then you earn buttons to view your inventory and to undertake a quest, and then you’re off.

Even that simple “world” opens up further from there: Completing quest areas rewards you with maps that take you to intriguing helpers that will bestow upgrades, like a riddle-slinging frog or a lollipop-crazed sorceress. Every additional discovery adds meaningful variation. And then the game gets meaningfully hard, redoubling the player’s investment in the grind. It always feels like there’s something new and whimsical around the corner.

Traditional “social gaming” experience.

The game gives the player very little direction or feedback, aside from an FAQ provided to answer very common sticking points. It’s so minimalistic that it recalls a beloved earlier age of games, when all of them were opaque and mysterious, and the only real way to progress was to share playground lore.

In the early stages of Candy Box, it seems impossible that there should be a dragon somewhere in the game, but while you’re still counting candies and fighting tree trunks for practice, seeing on Twitter that people are planting trees and using acid rain spells against a castle beast sounds like a myth you’re determined to see for yourself.

As childhood gamers, everyone always had that friend with the false boast about what happens later in a game you yourself can’t conquer. Or you learned about secrets and easter eggs through rumor and conversation, things you never thought to try for yourself.

Candy Box is loaded with easter eggs — it might never occur to you to click on the Candy Merchant himself until he reacts, but there’s a small reward to be found by pestering his hat or his beloved lollipop accessory, and you wouldn’t know that unless the rumor had spread from someone who’d figured it out. Gamers often fondly miss the days when gossip and lore were the only real direction through a forbidding, mysterious interface, but Candy Box brings that back.

Total accessibility.

Candy Box is incredibly low-stress, requiring only an open browser tab. You can save your game just via a bookmark button. You’re racking up resources just by leaving it open while you work or read or compose emails at your computer.

Since the game allows you to make investments to speed up your resource production, only a few clicks can make just the act of leaving the game on increasingly-gratifying. Actual gameplay, like questing, making purchases or preparing potions and spells in your cauldron (a relatively-later gift) takes only a couple minutes at a time, and then you basically have to leave it alone again.

Social games have depended on these kind of time mechanics to craft experiences intended to be pleasant background noise. But while most designers and critics found Facebook city-builders to become demanding, addictive nuisances constantly intruding, less than an hour with Candy Box illuminates the appeal of having a low-friction game as a kind of daily companion, one tab over from your work, rewarding you quietly in the background.

Candy Box never makes a demand on your time — no alerts, no notifications, not even a humble pop-up asking players to share the game with friends, even though its opacity makes it a game most successful and meaningful when shared as part of a community experience and discussion.

It seems like if you don’t force players to engage others, and don’t try to moderate their use of time, a game can be viral and time-dependent on a purely voluntary basis. That’s a powerful thing.

Charming minimalism.

No doubt Candy Box’s ambiguous author, charming old-school ASCII art and use of only one window helped earn player loyalty and imagination. Imagine the same exact game with brightly-colored, cartoonish customizable characters, illustrated words and animations. Even the addition of sound effects would have impacted the experience negatively.

Its visual innovation is to be reserved yet creative within constraint, and through that choice it never gives the impression it’s going to overwhelm or burden either players’ attention or their device performance. Half the fun of playing Candy Box is discovering what its mysterious creator will invent next with such simple visual resources. The most lightweight, handmade look and feel possible seems to benefit games that aim to provide simple but deep distractions.

Brevity.

The Candy Box craze is already ebbing, having hit peak fervor after only a few days. That’s because it’s easy to feel “done” — the main game only takes a couple days of sustained attention to complete, and while there is an intimidating end game, only the most obsessive players seem to persist with it, since there is a sense of actual accomplishment and fulfillment to be found after a reasonable degree of investment.

The game doesn’t seem motivated by the desire to keep people staring at it for as long as possible, and feels comfortable with creating a meaningful arc within a relatively-simple system. That may fly in the face of the conventional need to keep players doing something for as long as possible, but that Candy Box doesn’t overstay its welcome or become a genuinely-unfriendly time suck is part of why there’s so much goodwill still hanging in the air toward it even after the fervor dies down.

What about monetization?

“Aniwey,” the game’s creator, could certainly parlay that good will into other projects, now. The creator says there’s already a sequel underway, but a good hunch suggests that in the event they decided to solicit donations of some kind as a show of support or to enable more single-tab ASCII adventures, satisfied players would respond. I definitely feel like my time with Candy Box was worth a few dollars; if thousands of others felt the same, the creator could be on their way to launching a formal community.

It’s often the games that seem either disinterested in or oblivious to “best practices” of traditional design, particularly in the systematized and alienating social arena, that become accidental overnight hits. In Candy Box we now have an important lesson — people don’t necessarily hate grinding. Or social play. Or timed engagement, or even games that are basically spreadsheets skinned with a graphical interface. They just hate nearly everything the social games business has tried to feed them so far. Looks like something a little bit sweet can go a long way. (source:gamasutra)

上一篇:分析8种游戏玩家人格的类型及特点

闽公网安备35020302001549号

闽公网安备35020302001549号