解析7大游戏设计风格及系列设计建议

作者:Danc.

我曾试图询问朋友喜欢制作什么类型的游戏,而我发现我竟不知如何巧妙组织问题。我发现游戏具有特定风格。这些不是视觉风格。游戏风格也和首选开发过程毫无关系。相反,它们有独特游戏设计风格,混合和搭配机制、故事、玩家身份和反馈方式的模式也别具一格。你强调什么?你的设计选择强调何种玩家体验?

设计风格类型

这是个宽泛话题,所以我会直接切入。下面是我发现的若干游戏风格。你可以把这些类型想象成游戏最终设计内容的组成成份。虽然所有风格都存在,但每个风格在特定游戏的体现程度都不同。

1. 模仿:模仿另一有趣游戏制作内容

2. 体验:制作某趣味横生的游戏时刻

3. 叙述:创作有趣故事

4. 空间:创造有趣地点或世界

5. 机制:制作有趣机制和物品

6. 玩家技能:创造有趣玩家动作

下面就来简短描述每种风格及其运作方式。

模仿

模仿设计师基于既有游戏类型添加新内容。“模仿”一词在此属于描述性,而非嘲笑性质。我个人很喜欢从其他游戏中“窃取”内容,我觉得“窃取”是任何设计师都需要的技能。

* 模仿者从之前作品中借鉴最佳元素,然后以最小设计创新将他们混合起来创造新流行趋势。

* 若出现设计问题,最佳解决策略通常出现在同类游戏的以往作品中。最佳模仿设计者熟知其他同类游戏内容。

* 目标通常是创造比既有内容更优质或“更准确”的作品。

多数设计师都是模仿者。从供给方来看,热衷某类游戏的玩家通常会产生制作更优质内容的欲望。这给市场带来源源不断的新模仿设计师。从需求方来看,消费市场渴望续集,这就使得大量开发工作都需要复制设计。此趋势之所以能够维系是因为成为模仿设计师并不困难。寻找你喜欢的游戏,然后进行复制。你无需掌握理论或强大设计哲学。经过多年付出,你将能够在基于原始模型制作优秀衍生内容上得心应手。

局限性

* 竞争激烈。多数时候你都是在某数量饱和的游戏类型中抢占市场份额。你可通过建立强大既有品牌避免竞争(游戏邦注:这成本颇高),或者选择开拓新平台(这需要技术资源及要求开发者能够预测市场趋势)。

* 成本颇高。大量完善工作意味着你需要较长开发周期,庞大团队和高额营销预算。

* 风险规避置于首位:模仿玩家和开发者都积极回避风险。玩家希望能够顺利进展,开发者不希望在原本就有资金风险的项目中引入过多设计风险。这通常只会形成不一定是更优内容的大型作品。

体验

体验设计师脑中通常已有游戏大致轮廓,知晓游戏总体外观、风格和音效。他们希望给玩家带来符合其预期的情感体验。

* 体验设计师从游戏心智图像着手。这或许是个静止画面,或许是个场景,或许是充满感人细节的场景。

* 所有游戏元素旨在呈现此影像。

但谈及体验风格作品,我立马想到《Flow and Flower》。《Graveyard》也是个典型例子。从目标体验着手益处颇多。你可以改变画面、机制、故事和其他游戏元素,配合体验内容。体验设计使得原生作品设计师地位显著,几乎无可替代。游戏场景几乎都存储于他们的脑海中,他们是评判实际作品是否符合设想的最终裁决者。

局限性

* 基于设想的设计无法沟通。在大型团队中,沟通失误将加重项目工作,使项目陷入困境。

* 团队将周旋于各种不同路线,无法把握设计师脑海中的短暂构思画面。

* 有时其他玩法元素将无法获得充分体现。你能够轻松制作出外观突出的作品,但其也许不那么有趣。

叙述

故事设计师都有其故事,通常是他们希望叙述的呈直线顺序发展的感人事件(或者是这些事件的图表)。游戏是故事叙述的舞台。

* 游戏通常被想像成叙述脉络,玩法被视作将各部分联系起来,支撑故事脉络形成的迷你游戏。

* 设计工作通常通过关注符号和节奏引起情感共鸣。当设计师消灭或去除某角色,而玩家无能为力时,你就知道故事设计师的重要性。

* 若玩家在体验过程中给予故事内容强烈反应,说明游戏是个成功作品。

故事设计师通常制作大型作品。很多AAA游戏都采用叙事设计倡导的“过山车”结构。出自故事设计师之手的作品无处不在。《Choose your own adventures 》就是个经典例子,但令我感到惊讶的是就连《Passage》之类的游戏也被视作具有固定结局的故事。

局限性

* 多数基于故事的游戏,玩家玩过1、2次后就不再感兴趣。游戏已传递其故事,变得毫无价值。

* 所有精选叙述内容都限制部分玩家自主权。游戏未让玩家创作自己的故事,相反,设计师介入其中,将其自身叙述故事强加给玩家。这限制玩家尝试和学习新事物的自由。

* 此类游戏很少融入失败元素,或者至少不会将失败作为重要元素。毕竟游戏存在某个必须叙述的故事。通常玩家只消付出极小努力便能从某个故事转折点转移至另一转折点。

空间

空间设计师以设想虚拟空间开始设计工作。他们以玩家角度设想游戏空间。

* 地点是个决定性的组织概念。道具、角色和组织都存在于特定地点中,其空间关系赋予游戏世界实际含义。空间设计师通常以地图、建筑、村庄、种族、公会和地区角度思考问题。

* 大多地点的风味都是通过历史细节形成。基本假设是玩家消失后,游戏世界就出现,玩家离开,游戏世界就会出现。

* 空间设计师通常通过新画面内容创造置身该世界的情感效果。他们通常始终都使用相同游戏机制,但通过变化地点背景取悦玩家。

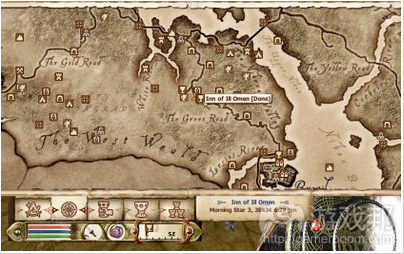

空间设计师的典型作品出现在纸质角色扮演游戏世界。开发公司高管通常会从绘有各大洲的地图着手,将文明、种族和联盟元素具体化。《创世纪》、《Oblivion》和《魔兽世界》之类的游戏通常具有强烈空间风格。

局限性

* 空间设计通常形成大型作品。你脑中不断发展的游戏世界存在众多元素,因此你很难获悉何时停止添加内容。所创造的新机制和动作旨在探索世界各个角落,鲜有机制以新鲜方式进行联系。

* 空间设计需耗费大量工作。制作单个场景或情景要比呈现整个世界简单得多。

* 设计师通常过于注重创建游戏空间,以致忘记在其中添加有趣内容供玩家体验,结果形成毫无生气的呆板空间。

机制

机制设计师通常以系列有趣规则(游戏邦注:这些规则以意想不到的方式相互作用)开始设计工作。

* 设计师通常通过系列物品、道具及物品间的有趣作用方式开始设计。

* 灵感普遍来源包括概率、组合学、空间关系、物理现象、时机和经济博弈论。

* 目标是给玩家创造挑战,不论是谜题形式的短期挑战,还是深层可能空间形式的长远挑战。

* 深刻系统通常会曝露其机制,以便向高级玩家清楚呈现其内部运作方式。结果游戏给予叙述或空间创建之类的细节内容极少空间。

众多业内原始玩法形式都是出自受系统启发人士之手。设有简单规则的代表作品是《俄罗斯方块》,而复杂系统的代表作品有《模拟城市》和《上帝也疯狂》。

局限性

* 作品机制通常能够吸引设计师眼球,但在玩家看来却不那么有趣。

* 很多瞄准设计的机制在玩家看来相当抽象。游戏未给予新玩家清晰设计入口(游戏邦注:以亲切暗喻或背景形式)。

* 由于各种意外出现的互动,机制很难获得平衡。

玩家技能

关注玩家技能的设计师能够创造系列动作供玩家操作。他们创造帮助玩家学习此技能的机制。

* 你通过书写希望玩家操作的动作开始设计。

* 然后你会开始研究适合这些动作的机制。

* 你弄清当系统呈现于玩家面前时,还需何种额外技能。

* 最后你设计正确反馈机制,以愉快方式向玩家传递技能内容。

宫本茂就是个受玩家动作启发的设计师。当制作这类游戏时,他倾向关注玩家行为。《Mario》原本根据游戏核心动作取名“Jumpman”。《WiiFit》是款基于自称体重活动而创建的游戏。《Mario 64》是基于游戏测试床内容的作品,游戏玩家所要做的就是奔走于小房间中,练习游戏基本活动。

局限性

* 当设计师借助最简单的系统呈现特定动作时,游戏玩法有时会演变成系列分离迷你游戏。例如,在《FishingGirl》中,我使用Frogger风格机制呈现钓鱼元素。作为模仿这相当局限,其几乎同其他投掷和购买鱼饵的迷你游戏毫无关系。在《战神》中,其把“杀死领头怪物”动作变成简单迷你游戏“Simon”。

* 确立系列有趣动作后,叙述和空间只是进行润色。这将形成包含蘑菇、炮弹爆炸画面和其他视频风格的超现实游戏世界。

新兴游戏风格

以下风格开始在系列游戏社区中崭露头角。

社交型:是指鼓励多玩家间特定类型的互动风格。此内容设计师能够协调项目或者组织派对,关注气氛,懂得打破僵局,转移各互动的玩家,能够有效创建和取消项目。他们坚持的重要组织理念包括“活动”和“社交空间”。MMO、派对和社交网络游戏倾向吸引社交设计师。我觉得下批优秀设计师将会是社交游戏设计师。

商业性:关注商业内容,企图从玩家身上榨取尽可能多利益的设计。我接触过以此设计理念投身在线游戏和赌场游戏领域的设计师。一般来说,如今已转至发行领域的前设计师就是持这种设计观点。这是个强大而少见的视角。随着免费模式越来越普遍,玩法和商业模式将更融为一体。

产品易用性:首先关注玩家价值的设计师能够识别产品带给玩家的易用程度。关注易用性的设计师通常来自传统设计领域,注重创造创新解决方案,解决既有问题。雅虎、亚马逊、Iminlikewithyou及众多web 2.0公司都忙于通过游戏创造性内容,谋求功利。总而言之,这是个有目的的社交编程。

选择适合自己的风格

很多设计师都倾向混合各种风格。例如,喜欢致力授权领域的开发者常通过空间风格着手,然后深入挖掘,理解授权内容的空间世界。随后他们会通过模仿设计进行扩充。或者,致力艺术游戏的设计师通常会把强大叙述内容同瞄准系列机制的系统结合起来。

我认为大多设计师都无法把这些风格均衡应用至同款游戏中。首先,每个风格都需花费几年努力才能掌握。其次,游戏需有所侧重方能传递其预期价值。过多突出元素同时抢占玩家时间会弱化最终成果(游戏邦注:这有点像烹饪)。

不妨参考投放市场的众多游戏,看看你是否能够辨别其融入多少风格。《光晕》就是款外表由叙述元素粉饰(旨在让游戏看起来更庞大)的模仿游戏。《Desktop Tower Defense》是款动作和机制游戏,几乎不含有其风格。博格斯特在“程序主义”中谈到贾森·罗勒的作品。他的游戏是叙述和机制风格的有趣结合。

所以设计作品时,选择2-3种风格。将某个风格置于主导位置,然后把其他内容放在次要位置(以免在随后设计过程中出现冲突)。不要忽视剩余风格,因为某天你或许会需要其中某些内容,制作游戏功能。但注意你所制作游戏的主流风格,预先决定好关注焦点。

理解设计风格能够减少团队冲突

通常某些团队成员或玩家会是其他游戏设计风格的粉丝。我经常碰到游戏行业杰出人士热情洋溢地想要陈述他们在电影中看到的感人故事。对他们而言,故事和体验非常重要。但任何有关机制的沟通都必然会演变成混乱的模仿讨论。

人格测试用于解决不同工作风格人员之间的冲突,同样你也可以通过类似方式使用上述设计风格。

1. 确定个人风格。你喜欢上述那些风格?觉得哪些内容呆滞或令人生厌?

2. 确定目前致力的游戏风格。这点通常不同于个人风格。公开宣布正在制作游戏的风格,这样整个团队才会就游戏方向保持一致。

3. 看看自己是否能够理解周围大谈特谈游戏设计人士所偏好的游戏风格。

4. 需明白团队有成员着迷其他各种风格是好事。因为千奇百怪的观点并不意味着其毫无价值。

5. 当需在个人风格之外添加些许“香料”,是否能够充分利用偏好此风格人士的热情。我们无法始终在各个领域保持领先,也不应将此作为目标。

我的风格

我总是以机制视角着手新设计。发现系列以有趣方式互相交织的目标后,我就会试图以此创建游戏。我通常的过程是尝试各种机制,然后进行测试,看看哪种“有趣”。这要耗费大量劳动,但你能够通过使用小型灵活团队和简单模型降低成本。这会形成偏向模仿元素的游戏。但其还存在超现实元素,因为体验、故事和空间通常都是当场进行再次想象,以适应最新机制。

最近我更倾向动作风格。在机制风格中,我通常都制作设计过程趣味横生的作品,但体验起来却不那么有趣。通过瞄准动作风格,把握机制如何帮助玩家学会操作,我的模型更常“发现趣味”。若游戏通过探索学习创造乐趣,那么我们就可以说瞄准动作和技能是创造迷人游戏玩法的更直接方式。

叙述是我弱点,是我应投身的方向。

总结

游戏设计没有标准风格。就宫本茂和威尔·赖特作品而言,总存在诸如《猴子岛》和《极速天龙》之类的积极故事和体验。大家都喜欢这些游戏。游戏设计风格和其他消费市场的风格一样,只是个品位问题。好消息是如今我已能够制作各种不同风格的内容,以不那么模糊的方式讨论它们。

我更年轻些的时候更关注基于体验的游戏设计。我清楚记得我曾致力某款以疾病为主题的作品,我极力说服团队同伴,令邪恶癌细胞离开玩家。但随着年龄的增长,我开始转投更理智,不那么情绪化的设计。若某天能够重新着手我年轻时的设计应该会非常有趣。

当然此游戏设计风格列表还处在不断完善中。所以最后我以两个问题结束本文。

* 你是什么风格的游戏设计师?你适合其中某一模式吗?

* 此列表是否还错过其他设计风格?其是否能够通过其他风格的结合进行呈现?

游戏邦注:原文发布于2009年3月1日,文章叙述以当时为背景。(本文为游戏邦/gamerboom.com编译,如需转载请联系:游戏邦)

What is your game design style?

By Danc.

I was about to ask a friend what sort of games she liked to make and I realized that I didn’t even know how to frame that question in an intelligent manner. I’ve noticed that games have distinct styles. These are not visual styles. Nor are they styles associated with prefered process of development. Instead, they are unique styles of game design, how you mix and match mechanics, story, player agency and feedback. What do you emphasize? What aspects of the the player’s experience do you highlight with your design choices?

A spectrum of game design styles

It is a broad topic, so I’ll just jump right in. Here are some styles that I’ve noticed. You can think of these categories as pieces of a spectrum that cover all major aspects of the final game design that the player experiences. Though they are all present, each style is emphasized to varying degrees in a particular title.

1. Copycat: make a game like another game that is interesting.

2. Experience: Make a distinct moment of game play that looks and feels interesting.

3. Narrative: Make a story that is interesting

4. World: Make a place or world that is interesting

5. Systems: Make systems and objects that are interesting.

6. Player Skills: Make verbs for the player that are interesting.

Let’s give a brief description of each of these styles and how I’ve seen them work.

Copycat

A copycat designer takes an existing game genre and builds a new work within it. The term ‘copycat’ is descriptive and not derisive. I personally steal with great gusto from other games and consider an elegantly pulled off theft to be an essential skill for any practicing designer.

* Copycats borrow liberally from the best elements of past works and mix them together with minor design innovations to create the new flavor of the month.

* If design problems arise, a good solution is often readily available in a historical product in the same genre. The best copycat designers have encyclopedic knowledge of other games in their genre.

* The goal is almost always to make something better or ‘more correct’ than what has been on the market previously.

Most working designers are copycat designers. On the supply side, there exists a natural urge for a player who deeply loves a particular genre to attempt to do a better job. This provides a constant wellspring of new copycat designers. On the demand side, the market’s lust for sequels ensures a wide range of jobs that need good copycat designs. Helping this dynamic is the fact that it is quite easy to learn to be a copycat designer. Find a game you like and copy it. You don’t need to know theory or have a strong philosophy of design. Over many years of labor you’ll likely get quite good at making polished variations on the initial blueprint.

Limitations

* Competition is intense. Most of the time you are fighting over market share in a crowded genre. You can avoid the competition by building a strong established brand (which costs lots of money) or you can be first to a popular new platform (which requires technical resources and the ability to predict future markets)

* Costs are high. All the polish required results in long development cycles with large teams and large marketing budgets.

* Risk aversion dominates: Both copycat players and developers are risk averse. Players want their comfortable fix and developers don’t want to introduce undue design risk in an already financially risky project. This often leads to bigger titles that are not always better.

Experience

An experience designer has a vision in their head of how the game will eventually look, feel and sound. They seek to create an emotional moment for the player that matches their vision.

* Experience designers start with a mental image of the game. It could be a still shot. It could be a scene. The scene is laden with strong emotional and evocative detail.

* Everything in the game exists to serve and bring to life that vision.

When I think of games that demonstrate the Experience style, I immediately think of Flow and Flower. Graveyard is also a good example. Starting with a target experience has a lot of benefits. You can change your art, mechanics, story and other game elements to match the experience. Experience designs have the added benefit of making the original designer valuable and nearly irreplaceable. The vision resides primarily in their head and they can act as the final arbiter of whether or not the actual product meets their vision.

Limitations:

* Designs based on a vision are difficult to communicate. On larger teams, communication mistakes can multiply and bog down the project.

* Teams can wander down dozens of different paths and still not reach the ephemeral vision in the designer’s noggin.

* Occasionally other game play elements are poorly fleshed out. You can easily end up with something that is pretty, but isn’t all that fun to play.

Narrative

A story designer has a tale, usually a linear sequence of evocative events (or graph of such events), that they wish to tell. Games are the stage upon which the story is performed.

* The game is conceived as a narrative arc and gameplay is often relegated to mini-game set pieces strung together to support the creation of the arc.

* Design efforts focus on the use of symbols and pacing to evoke emotion. When the designer kills or removes a character and there is nothing the player could have done, you know you are dealing with a Story Designer.

* The game is a success if players react strongly to the story that has been woven for them over the course of their play.

Story designers are quite common in larger scale games. Many AAA titles sports a very specific ‘roller coaster ride’ structure that has narrative design at it’s heart. Examples of games built by Story Designers are everywhere. Choose your own adventures are the classic case, but I’d be curious if even a game like Passage was ultimately conceived as a tale with fixed endings (albeit one where authorial intent was enforced by a predestined algorithm).

Limitations

* Most story-based games can only be played once or twice before they are no longer interesting. They deliver their tale and then their value is spent.

* Every little bit of must-see narrative steals a smidgen of agency away from the player. Instead of letting the player author their own story, the designer steps in and forces their own narrative upon the player. This limits the player’s ability to try and learn new things.

* Failure is rarely an option, or at least not a serious one. After all, there is a story that must be told. Many times players are shunted from plot point to plot point with minimal gaming fuss.

World

A world designer begins by envisioning an imaginary space. They picture how it might be if they escaped into it as a player.

* Place is a critical organizing concept. Items, people, organizations lives in specific places and their spatial relationships give meaning to the world. It is quite common for world designers to think in terms of maps, architecture, towns, races, guilds, districts etc.

* Much of the flavor of the place is created through the use of historical detail. The underlying assumption is that the world existed when the player was gone and it will exist when the player leaves.

* World designer will often lean heavily on fresh content in the form of new vistas to create a sensation of being in the world. They will often use the same game mechanics throughout, but delight the player by varying the setting from location to location.

The classic example of a World Designer is found in the paper RPG world. A GM will start with a map of continents and flesh out civilizations, races and alliances. This creates a playground for imaginative adventures. Games like Ultima, Oblivion and World of Warcraft also have a strong World style.

Limitations

* World designs can often result in bloated games. There is so much stuff in the ever evolving world in your head that it is hard to know when to stop adding. New systems and verbs are created to support the exploration of every nook and cranny and few mechanics interconnect in crisp manner.

* World designs are usually an immense amount of work. It is far easier to make a single scene or a situation than it is to flesh out an entire world.

* Designers can focus so much on building the space that they forget to fill it with interesting things for the player to do. The result is mechanical place that feels lifeless.

Systems

Systems designers begin with a curious and intriguing set of rules that interact in unexpected ways.

* Designs often begin with a set of objects, properties and interesting ways that the objects interact.

* Common sources of inspiration include probability, combinatorics, spacial relationships, physics, timing and economic game theory.

* The goal is to create a challenge for the player, be it a short term challenge in the form of a puzzle or a long term challenge in the form of a deep possibility space.

* Truly deep systems often lay bare their mechanics in order to provide advanced players with absolutely clarity on their inner workings. The result is less room for details like narrative or world building.

Many of the industry’s most original forms of gameplay were conceived by people inspired by systems. With simpler rule sets, you find games like Tetris. Complex systems yield creations like SimCity or Populous.

Limitations

* You’ll often end up with a system that is fascinating to the designer, but not that enjoyable to the player.

* Many systems oriented designs come across to players as overly abstract. There isn’t a clear entry point into the design for new users in the form of a friendly metaphor or setting.

* Systems can be quite difficult to balance due to all the various emergent interactions.

Player skills

Designers that focus on player skills create a set of actions (or ‘verbs’ in Chris Crawford lingo) for the player to perform. Then they create systems that help them learn those skills.

* You start by writing out the type of verbs that you want the player to perform.

* Then you figure out systems to go with those verbs

* You figure out what additional skills are discovered when the systems are put in front of players.

* Finally you figure out the right feedback systems to teach people those skills in an enjoyable manner.

Miyamoto is a good example of a designer inspired by player actions. When developing games he tends to focus on what the player is doing. Mario was originally named Jumpman after the key action you performed in the game. WiiFit came about by asking what sort of game could be built around the joy of weighing yourself. Mario 64 started as a playtest bed where all you could do is run around a small room and exercise the basic verbs of the game.

Limitations

* Game play occasionally devolves into a series of disconnected mini-games when designers grab the easiest system available to represent a particular action. For example, in FishingGirl, I used a Frogger-style mechanic to represent fishing. As a simulation it was quite limited and was barely connected to the other mini-games associated with of casting and purchasing lures. In something like God of War, they turn the action “Kill boss monster” into the simplistic mini-game “Simon”.

* After coming up with a set of fun actions, narrative and world are applied as a skin to the results. The result are surreal worlds involving mushrooms, exploding barrel graphics and other videogame-isms.

Rising design styles

The following styles are starting to appear within a few pockets of game design community.

Social: Designers that focus on encouraging particular types of interactions between multiple people. They have skills of event coordinators or party planners and focus on atmosphere, breaking the ice, moving people from activity to activity as well as efficient build up and take down of the event. Important organizing concepts include ‘Events’ and ‘Social spaces’. MMOs, Party games, and social networking games tend to attract Social designers. It is my believe that the next generation of great designers will be social designers.

Business: Design that focus on business try to squeeze as much money out of players as possible. I meet designers operating in online games and gambling games with this design slant. Typically, you encounter it in ex-designers who have moved onto publishing roles. It is an extremely powerful perspective that is unfortunately rather rare. As free-to-play becomes more popular, gameplay and business model will become even more interwoven.

Product Utility: Designers that focus on player value first identifies some form of utility that the product bring to the player. Product Utility designers often come from a more traditional product design background and focus on creating innovative solutions to observed problems. Yahoo, Amazon, Iminlikewithyou, and numerous web 2.0 companies a busy using the motivational aspects of games for utilitarian purposes. In short, this is social engineering with a purpose.

Pick your style!

Most designers tend to mix a couple major styles together. For example someone who enjoys working on licenses might start with a world style and do a deep dive to understand the world of the license. Then they augment that with a copycat design. Or someone who works on art games could mix a strong narrative with a systems oriented set of mechanics.

My suspicion is that most designers will have trouble applying all these styles to a game equally. First, each style can easily take years of intense labor to master. Secondly, games need focus in order to clearly convey their intended value. Too many dominant ingredients fighting for the player’s time can weaken the end result. It is a bit like cooking.

As an exercise, take a look at various games out on the market and see if you can figure out the handful of styles they’ve stirred together. Halo is classic Copycat with a heavy coating of Narrative to make it seem like something bigger than your typical game. Desktop Tower Defense a straight Verb and System game, barely seasoned with any other styles. Ian Bogost refers to Jason Rohrer’s work at ‘Proceduralism’. I see a fascinating mix of Narrative and System styles.

So pick two or three styles for each game you build. Prioritize one as primary and others as secondary (in case there is a conflict at some point later in the design.) Don’t ignore the remaining styles since you’ll certainly need dashes of them to make the game function. However, be conscious of the dominant style of game you are making and make the hard decisions on what to focus on up front.

Understanding design styles to reduce team conflict

Inevitably there will be people on your team or in your audience who are fans of the other styles of game design. I regularly run into good people working in the game industry who passionately want to tell the sort of emotional stories that they see in movies. Story and Experience are paramount to them. However, any sort of Systems conversation inevitably devolves into a muddled Copycat discussion.

You can use the game design styles above much like how personality tests are used to resolve conflicts between people with different work styles.

1. Identify your personal style. Which of those styles above do you love? Which ones do you find dull or unpleasant?

2. Identify the style of the game you are working on right now. It is very common for this to be something different than your personal style. Publicly declare the style of game you are making so the entire team can agree upon the game’s direction.

3. See if you can understand the preferred style of other people around you that tend to hold forth passionately on game design.

4. Realize that having people on the team who are passionate about a variety of different styles is a good thing. Just because you occasionally feel the other person is coming from a bizarre and alien perspective doesn’t mean that they don’t have something valuable to contribute.

5. When the opportunity comes to up to add in a dash of ‘spice’ in an area outside your personal style, see if you can tap into the passion of someone who prefers that style. We can’t lead all the time in all areas, nor is it a good idea to try.

My style

I almost always approach a new design from a Systems perspective. I find an interesting set of objects that interact with one another in interesting ways and then attempt to build a game around it. My typical process is to try lots and lots of systems, throw them at kleenex testers and see which ones are ‘fun’. This is labor intensive, but you can keep the costs down by using small agile teams and simple prototypes. It yields games that are lower on the copycat factor. However, they also have a bit of a surreal aspect to them since experience, story and world tend to be re-imagined on the spot to fit the latest mechanics.

Lately, I’ve been moving more in the direction of a Verb style. With Systems, I’ll often end up creating a game that is fun to design, but not fun to play. By focusing on the verbs and how the systems help the player learn to manipulate the system, my prototypes “find the fun” more often. If games create pleasure through exploratory learning, it makes sense that focusing on verbs and skills are one of the more direct paths towards creating engaging game play.

Narrative is my main weak point and something I should work on.

Conclusion

One thing I get out of this exercise is that there is not one True style of game design. For every Miyamoto and Will Wright creation there is a game like Monkey Island or Full Throttle pushing story and experience. People love all these games. Game design style, like style in almost any consumer market is a matter of taste. The good news is that now I can name the various styles and discuss them in a less vague fashion.

I also realize that I’ve been leaving certain powerful perspectives out of my palette of game design tools. When I was younger (and driven more strongly by raging hormones), experience-driven games mattered immensely. I vividly remember working on a game about sickness and trying to convince my fellow teammates that it was of utmost importance that black cancerous growths fall off the player and scuttle away on their own. As I aged, I’ve moved onto more intellectual and less emotional designs. It might be fun to bring that side of my design back one day.

Of course, this list of game design styles is a work in progress. So I’ll end with some questions.

* What style of game designer are you? Do you fit into one of these approaches?

* Is there another design style that is missing from this list? Can it be expressed by a combination of the other styles?(Source:lostgarden)

上一篇:异步游戏的优点及其机制的发展方向

下一篇:游戏设计师不可盲从所有用户的需求

闽公网安备35020302001549号

闽公网安备35020302001549号