长文分析:由游戏制作人员名单所引发的行业思考

长文分析:由游戏制作人员名单所引发的行业思考

原作者:Richard Moss 译者:Willow Wu

你们肯定会觉得展示游戏制作人员名单是再简单不过的事了。

不就是名字、职位而已吗?这能有多难?

但其实这对大多数开发者来说并不是一个轻松的任务。它在游戏制作中起着重要作用,然而却不受重视。

制作人员名单是我们对游戏开发人力投入的最好、也是唯一的记录方式,它不仅能够提醒我们游戏是由人创造的——有时是许多人——同时也是开发者获得职业生涯发展的有力工具。

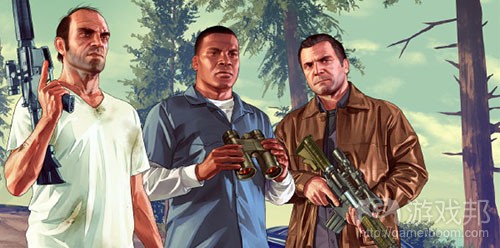

对于游戏公司来说,制作人员名单是有利用价值的。就比如前段时间Rockstar压榨员工的新闻让人们愤怒不已,我们了解到这家公司的一贯政策是没有全程参与游戏开发的员工不会出现在制作人员名单上,他们称这么做的目的是鼓励团队共同抵达终点。

对于历史研究者和记者来说,它是揭开真相的一个入手点。他们能够借此挖出游戏开发者、公司的背后故事。

尽管制作人员名单很重要,但是在发行游戏时出现不准确、不完整、信息过于模糊、甚至(在极少数情况下)严重误导的情况并不罕见。原因有很多,Fun Bits CEO Chris Millar在去年的采访中跟我说了其中主要的一个——游戏人员制作名单没有标准规范。

“虽然比起从前好了很多,但是在这方面我们跟电影行业还有很大差距,”他说。

国际游戏开发者协会(IGDA)最新一版的名单指南还是2014年发布的——在此之前的10年里,发生了多起备受瞩目的制作人员名单丑闻,比如《侠盗猎魔2》的一个55人工作团队没有出现在名单中。数年来围绕名单标准重要性的讨论一直都没有停止。但是这些指导文件很难接触到,再加上缺少工会协议,出版商可以自行决定是否遵循这些指导——如果他们知道这些东西存在的话。

为了让大家更清楚了解制作人员名单是如何帮助、阻碍、扭曲或者是影响游戏历史和档案记录,思考制作人员名单标准能起到多大的作用,我跟四位历史学家和几位开发者请教了这个问题。他们的故事揭示了在游戏开发过程中人力、著作权、所有权以及身份识别之间的复杂关系,当然还有关于未来的展望。

名单的真实性

纽约大学斯坦哈特学院传媒专业的助教Laine Nooney花了很多年时间研究游戏公司Sierra On-Line,他说“游戏制作人员名单的出现实际上反映出了人们对创意产品著作权和所有权的重视。”名单的作用是提供一份创意产品的真实记录,但是正如Nooney所说的,这其中也会牵涉到一些政策因素。

“雅达利管理层规定公司游戏中不能出现设计师的名字,这就是一种对设计师权力的压制,这样一来,涉及到著作权方面的谈判筹码就都在他们掌控中了,”她解释道。但是事情并没能如他们所愿。Warren Robinett在1978年雅达利VCS游戏《冒险》中把他的名字藏在了一个密室中。另外有5位资深程序员对这个政策十分不满,他们毅然离开雅达利,成立了动视。雅达利损失惨重但这个结局讽刺至极。

游戏历史研究者Jimmy Maher在他的博客中列举了其它例子:“电子产品零售商Radio Shack也曾因为不愿意在TRS-80游戏中展示开发者这名字而招致批评,”他说。“甚至在Infocom这样较为开明的公司中,人们也一直在讨论创作者的名字该不该在游戏中强调、如果要的话应该怎么做。”

Maher说有些人认为创作者的名字应该写在包装盒上,而另外一些人根本没有把这事放在心上,只想让Infocom成为一个知名的品牌。”

有关于制作人员名单与公司品牌之间的历史争论,你挖的越深就会觉得越有趣。MicroProse公司领导人Wild Bill Stealey就曾把《文明》系列之父Sid Meier的名字当作品牌宣传工具。Sid Meier’s的标签不仅出现在他主创游戏的标题中,就连只是以咨询师的身份参与的游戏也有这个前缀。

Maher补充说Origin Systems的《创世纪外传1:洪荒帝国》(Worlds of Ultima: The Savage Empire)同样把Richard Garriott以执行制作人的身份纳入到游戏制作人员名单中,尽管他并没有为这部游戏做出什么实质贡献。而负责概念设计、环境、剧情大纲的Warren Spector却没有在名单中。

政策成为阻碍

其实你可以从制作人员名单看出一个公司的内部政策,因为它是由实际项目和公司员工职位所决定的。这对历史研究者来说就是有趣的入手点,但他们首先得知道哪些人是因为政策原因被纳入或者是剔除。

这可能导致历史的埋没,就像Arthur Abraham一样,他为Sierra《国王密使》(游戏邦注King’s Quest)开发了原型脚本语言和游戏逻辑,也就是后来的AGI引擎。“Abraham在《国王密使》开发中途就被解雇了,”Nooney解释说,“除了Apple IIe版本,其它所有版本的游戏中都没有出现他的名字,包括Sierra之后14款应用AGI引擎的游戏。”

Nooney经过几次采访和大量资料研究,前后花了好几年才知道Abraham是AGI引擎开发的关键人物。“我想联系他的时候,他已经在狱中去世了,”她继续说。“如果我一开始就知道他是AGI引擎的创始人,或许我就能早点跟他取得联系,了解《国王密使》的开发过程——他们用错误信息掩盖了真实的开发工作。”

很多发行商都有(或者曾经有)这样的政策:如果开发人员在发行游戏之前离开项目,他们的名字不会出现在制作人员名单中。我在Polygon《刺客信条》口述历史专访时了解到,游戏制作人员名单“additional”底下的那些名字都是游戏的核心团队成员,但是他们在开发工作未全部结束之前就离开了。《星际争霸》的设计师Ron Millar在游戏测试期间跳槽到了动视(讽刺的是现在暴雪隶属于动视),所以他的名字只能出现在“special thanks”底下。

有时候甚至会出现整个游戏工作室都不会在名单中出现的情况。《日本游戏开发者的秘史》(Untold History of Japanese Game Developers)系列作者、游戏媒体人John Szczepaniak表示Namco公司不允许任何在日本公开参与其游戏开发的工作人员的姓名。(然而这并不能阻止Szczepaniak在日本之外地方分享——他已经拿到了《吃豆人》街机游戏的制作人员名单。)他补充说初代《恶魔城》在发行时是没有制作人员名单的。在进行地毯式搜索后,Szczepaniak和他的同事们唯一得到的有价值信息就是游戏主创是赤松仁志,但很遗憾无法联系到他。

同时,“贴牌”外包(公司受合同约束必须保密一切游戏开发工作)已经存在好几十年了。TOSE,一家日本游戏工作室,他们每年要开发30~50个游戏,而只有一小部分游戏会出现他们的名字(奇怪的是,这还是客户要求的,出于业务原因这些人希望保持匿名)。

Szczepaniak在2006年就有为The Escapist杂志写过关于“影子开发者”的文章,也就是像TOSE这样的人群,他认为应该有某种国际监管机构来阻止这种情况的发生。“所有员工的努力都应该让大家知道,”他说。

即使是很小的独立游戏或者是业余爱好者做的游戏也存在这种情况。“对于小型独立游戏,比如粉丝自制游戏或者免费应用来说,最大的问题之一就是缺少制作人员名单,”图书&档案管理员Phil Salvador说。他运营着一个名为The Obscuritory的博客,其中都是关于无名、被遗忘的游戏。

“有时候开发人员会使用假名或公司名称,或者他们会故意不写自己的名字。这是可以理解的,不是每个人都想在工作中使用真名,也不是每个人都想和他们14岁时一起玩的一个奇怪游戏扯上关系。”

但是当他们这么做时——无论是专业人士开发的商业性质游戏还是业余爱好者做的非商业性质游戏——也给历史研究者们带来了令人头疼的问题,他们无法知道这个游戏是怎么做的、什么时候做的、初衷是什么,或者是他们因此无法完善游戏目录。“就算是有个小小的署名也好,这样我们就可以根据线索展开搜寻,” Salvador说。“有的游戏公司倒闭了,记录文件基本上都丢了,游戏中出现任何一个名字都可能给我们提供很大的帮助。”

迷失于文化差异中

把制作人员名单当作入手点来揭开西方游戏背后不为人知的历史,这听起来似乎是个很大的挑战,那么你想想那些深入研究日本游戏产业的人吧,简直是大海捞针。“你都无法想象要挖出日本游戏开发者名单有多艰难,”Szczepaniak说。“摸着线索进入一个兔子洞,然后你发现得到的问题比答案多得多。”

就像其他受访的历史研究者一样(还有据我个人经历来说,其他人也是如此),Szczepaniak将MobyGames视为名单制作的重要参考。它的快速交叉参照功能对研究来说是非常宝贵的,而且这个网站不断在优化:比如列出日语名字的汉字、区分同名人等等。

这是一个极其复杂的问题。Szczepaniak表示,对于日本游戏来说,一个完整准确的人员名单系统应该要有汉字、平假名、振假名(指汉字上方或周围附注的假名注音符号。)还要有正确的罗马音。另外还得有方法区分名和姓(在他的书中,日本人的姓全都以大写的形式展现出来)——因为日本人的传统是姓放在前,而西方人是放在后面。

Szczepaniak举了Naoto Ohshima这个名字。“实际上有这样发音的名字在游戏行业就有三个人,他们分别为不同的游戏工作室工作,手头做着不同的项目,”他解释说。“一个在世嘉工作(大岛直人,《索尼克》系列设计师),一个在ASCII工作(《巫术》系列设计师),另一个在Konami工作(《寂静岭》系列程序员)。在很长一段时间中,有不少网站分不清世嘉和Konami的这两位员工,认为他们是同一个人。

甚至Sega-16(世嘉信息的主要参考网站之一)也是如此。后来还引发了连锁反应,这个张冠李戴的状况扩散到维基百科等多个网站。

“这就是因为非英语名字缺少汉字标注,” Szczepaniak说。“这三个人的名字发音完全一样,但是Ohshima是完全不一样的汉字。”

还有更容易搞混的。“这个问题也可以反过来,不同人名字的汉字完全一样,但发音各不一样,”Szczepaniak说。就比如宫本茂(Shigeru Miyamoto),在早期的NES游戏中,他的名字被写成了Shigeru Miyahon。Szczepaniak说就连日本本地人都觉得他名字的读法令人困惑。于是公司干脆就在名片上标上平假名,让别人知道这个名字的正确读法。Human Entertainment的Masatoshi Mitori就要求姓氏不要用汉字写,因为他们家使用的是古日语,没几个人认识。

其次,日语对话中没有性别代词,这意味着在采访中提到一个名叫“Suzuki-san”的同事可能指的是一个姓铃木的男人或女人——如果这是一份已经存档的采访,要弄清性别就不是那么容易了。你以为上面说的够复杂了?不,还没完!日本游戏开发者有时可能会使用昵称而不是真名。

Szczepaniak解释说这种情况不一定是程序员想要耍酷。有时是发行商的要求。“世嘉公司就经常这么干,Tecmo也是,”他说。“理由是防止被猎头盯上。这些公司特别害怕自家的资深程序员会被竞争对手抢走,同时也是为了避免日后可能出现的版权纠纷。大岛直人说世嘉不允许员工用真名署名,这就意味着公司对所有内部创作内容有着百分百的掌控权。

以小见大

现实情况是,制作人员名单只是游戏混乱历史的冰山一角——其它还涉及到公司内部、团队内部以及个人之间形成的复杂权势结构、媒体的协作以及众多公司和项目背后庞大的正式和非正式的后援组织。

职位经常是流动性或者是非正式状态。也许你刚进公司时做的是编程工作,但是到最后你会成为编剧或者是作曲人或者其它什么。当我在为写作收集资料时,我读了《Mac游戏的秘密历史》(The Secret History of Mac Gaming),我了解到早期Mac游戏《爱丽丝梦游仙境》的最终成果不仅要归功于它的创作者Steve Capps,还要归功于Macintosh营销代表Joanna Hoffman(她是办公室里最优秀的玩家)的一堆非正式要求和抱怨。

类似地,Salvador举了一个例子说1994年发行的游戏Millennium Auction的实际监制人是公司业务拓展部门的副总,但是他只能排在制作人员名单的特别鸣谢部分。

Nooney说这种情况在Sierra也很常见,那些有特定头衔的人参与游戏的其它方面的工作,但出于人际政治原因,他们的额外劳动并不会得到公开表彰。

这是一个两面性问题。人们可能会因为游戏开发之外的其它贡献而得到“感谢”,或者从一个夸大了他们实际贡献的职位头衔中获益,在职业生涯中更进一步。资深开发者Noah Falstein在他30多年的游戏生涯中遇到了各种各样的署名问题,他说他甚至曾经收到过某人的简历,说他曾参与过Sinistar——一个由Falstein领导并共同设计的街机游戏。

“我没有认出这个名字,”Falstein说。“我问了那个时期的同事,结果发现这个人之前是帮助我们把游戏打包装车的员工,所以严格意义上来说他的确有参与,但是跟他现在申请的职位并没有关系。”

不幸的是,正如Maher所言,由于制作人员名单长久以来都没有统一的标准、有时会与实际有所出入,我们不得不抱着怀疑的态度去考究。不管怎样,名单应该是一份值得信赖的参考来源。但人们未能如实地记录人们的劳动付出,这或许表明除了我们需要做的还有很多,而不仅仅是为了记录而记录。

“如果游戏公司能完整记录员工的付出,这肯定对未来的历史研究者很有帮助,”Nooney说。“但我认为,更大胆的一种想法是要认识到在以维护著作权为主要目的的基础上研究历史所带在的局限。除了搞清楚谁为这个游戏付出辛劳之外,我们还要需要思考哪些重要的行业问题?”

对于Nooney,还有所有研究宏观历史的行业内人士来说,内部组织结构往往比制作人员名单更有研究价值,因为你能从中分析整个公司的权力关系。还有就是大型企业或经济事件的记录,比如合并、收购、裁员、引发内部重组的关键人才引入、股市崩盘和IPOs。

“当我们把游戏当成是行业信息的主要来源时,我们往往会忽略这些重要的历史事件,”她总结道。

总结:游戏制作人员名单很重要,我们需要完整、真实地记录下来。但如果想要更好地了解游戏的历史,以及围绕它所产生的行业,光名单还远远不够。大家都必须学会如何更好地记录游戏的制作以及销售过程。

本文由游戏邦编译,转载请注明来源,或咨询微信zhengjintiao

You’d think that game credits would be simple.

It’s just a list of names and roles, after all. How hard can that be to get right?

But credits are rarely simple, because neither is game development. And yet credits are an invaluable, underappreciated aspect of game making.

They’re our best — and often only — record of the human labor that goes into game development, serving not only as a reminder that games are made by people — sometimes lots of them — but also as a tool for developers to advance their careers.

For studios, crediting can be a tool for leverage; amid the recent furor over Rockstar’s bad labor practices, for example, we were reminded that the studio has long maintained a policy of not crediting people who worked on a game unless they were present when it shipped, to encourage the team “to get to the finish line.”

For historians and journalists, meanwhile, they’re a way to begin to peel back the layers. To uncover the stories of the people and companies behind the games.

Despite their importance, however, it’s not unusual for the credits published with games to be inaccurate, incomplete, overly vague, or even (on rare occasions) downright misleading. This is a problem with many causes, but one of the big reasons, Fun Bits CEO Chris Millar told me in an interview earlier this year, is simply that credits in games aren’t standardized.

“While they’re much better than they used to be we’re still not anywhere near the movie industry,” he said, “in terms of giving people credit for all of their work on creative endeavors.”

Indeed, the IGDA published the last version of its crediting guidelines back in 2014 — after multiple high-profile instances of bad crediting in the decade before, including an entire team of 55 people being wiped off the credits for Manhunt 2, and a years-long discussion about the importance of credit standards. But those guidelines are hard to find and with no union agreements in place they’re for publishers to follow (or not) at their own discretion — provided they’re even aware that the guidelines exist.

In order to get a proper understanding of how credits can help, hinder, contort, and otherwise affect games history and archiving, and to start to puzzle out how much of a difference credits standardization would actually make, I asked four historians and a few developers about the issue. Their stories reveal a complex relationship between labor, authorship, ownership, and recognition in game development throughout the history of the medium — and no doubt long into the future.

A (flawed) record of authorship

“The fact that credits exist in games reflects human concerns about authorship and ownership with regard to creative production,” notes Laine Nooney, an assistant professor of media industries at NYU Steinhardt who has spent years researching and writing about the history of Sierra On-Line. The role of credits is to provide a factual record of this creative production but, as Nooney argues, they are also political.

“When Atari management made it policy to not list designers’ names on their games, this was an attempt to dis-empower designers by removing the bargaining power associated with explicit authorship,” she explains. It backfired. Warren Robinett hid his name in a secret room in 1978 Atari VCS game Adventure, and five other star programmers soon left in protest of the policy to start Activision — ironically taking power away from Atari as a result.

Warren Robinett’s famous hidden credit room, tucked away in Adventure

Games historian Jimmy Maher, who runs the Digital Antiquarian blog, points to other examples: “Radio Shack was also notorious for refusing to credit the people who made the TRS-80 games they carried in their stores,” he says. “Even at a progressive publisher like Infocom, there was a lot of debate over whether and to what extent the authors of the games should be highlighted, as opposed to the Infocom brand and the so-called ‘matrix’ of genres and difficulty levels.”

Some, Maher explains, thought their names should be on the box. Others “really couldn’t care less, and just wanted to make the Infocom brand successful.”

The historical relationship between credits and branding gets more intriguing as you dig deeper. MicroProse head Wild Bill Stealey — acting on a comment by the late comedian/actor Robin Williams about the games industry lacking recognizable stars — was responsible for Sid Meier’s name becoming a branding tool. The Sid Meier’s prefix soon came to decorate not only the titles of games that the Civilization designer led creatively but also the ones that he barely more than consulted on.

Maher adds that Origin’s Worlds of Ultima: The Savage Empire similarly included Richard Garriott’s name in the credits as an executive producer “despite having absolutely nothing to do with the game that I could discern.” (And meanwhile Warren Spector was left off the credits despite reportedly creating the concept, setting, and plot outline for the game.)

Politics gets in the way

Credits can be as much a reflection of internal politics as they are of actual project and company roles. While this gives historians interesting threads to explore, they must first become aware of which names are omitted or included because of politics.

This can result in history vanishing, as in the case of Arthur Abraham, who developed the prototype scripting language and game logic for Sierra’s King’s Quest and what would become the Adventure Game Interpreter (AGI) engine. “Abraham was fired part way through the development of King’s Quest,” explains Nooney, “and his name was left out of the credits of every King’s Quest port (with the exception of the Apple IIe version), as well as every future Sierra release that used AGI.”

Because of this, it took several interviews and extensive archival research, spread across several years, for Nooney to discern that Abraham was a key figure in AGI’s development. “He died in prison before I could make an attempt to contact him,” she continues. “Had I known at the start that he was foundational to AGI, I might have been able to correspond with him earlier and shed some light on the development of King’s Quest — a game which is shrouded in misinformation about its development.”

Many publishers have (or had) set policies of not crediting developers for their role on a project if they leave before it ships. I learned while conducting interviews for an Assassin’s Creed oral history at Polygon, for instance, that several people who appeared in the credits under the title “additional” were in fact core team members who left before the game’s four-year development concluded. Starcraft’s original designer Ron Millar was similarly relegated to “special thanks” in the game’s credits when he left to join Activision (which ironically now owns the entire company) while it was in testing.

Sometimes entire studios go uncredited for their work on a game. Games journalist and author of the Untold History of Japanese Game Developers book series John Szczepaniak notes that Namco does not allow anybody in Japan to disclose the names of staff who worked on any of its games. (Szczepaniak, however, has nothing preventing him from sharing those names outside Japan, and as such he has obtained a spreadsheet listing credits for the Pac-Land arcade game.) The original Castlevania was likewise published without credits, he adds. After extensive investigation, the best Szczepaniak and his colleagues can gather is that the main creator was Hitoshi Akamatsu — who they’ve been unable to contact.

Meanwhile, the practice of “white label” outsourcing — whereby companies are contractually-bound to keep quiet about their work on a game — has been around for decades. One Japanese studio, TOSE, reportedly works on 30 to 50 games per year and only receives credit for a handful of those (curiously, this only happens at the request of their clients — they have business reasons to want to stay anonymous).

Szczepaniak, who wrote about this world of “ghost developers” like TOSE for The Escapist back in 2006, believes there should be some sort of international regulatory body preventing this from happening. “Every staff member should be credited for their work,” he argues.

Even tiny indie and amateur games can wind up with names omitted entirely. “For small independent games, like fangames or freeware, one of the most difficult things is a total lack of credits,” says Phil Salvador, a librarian and digital archivist who runs a blog about little-known and forgotten games called The Obscuritory.

“Sometimes developers will only go by a pseudonym or a company name, or they’ll intentionally leave their name off. That’s an understandable problem without much of a fix. Not everyone wants to use their real name on all their work or to be associated with a weird game they threw together when they were 14.”

But when they do this — whether we’re talking commercial efforts made by professionals or non-commercial games by amateurs and hobbyists — they also cause a huge headache for historians, who might want to learn more about how/when/why a game was made or to build up a more complete catalog of games released. “Even minimal credits can be helpful for asking around and starting the research process,” notes Salvador. “With the companies often gone and their records presumably lost, anyone listed in a game’s credits is a potentially helpful source.”

Lost in translation

If it seems like a tough challenge to use credits as a jumping-off point to uncovering more of the history behind Western-developed games, spare a thought for the people digging into the Japanese industry. “You cannot even begin to imagine the Herculean task of disentangling Japanese credit listings,” says Szczepaniak. “And once you find a thread and follow it down the rabbit hole, you just bring up more questions than answers.”

Like the other historians interviewed for this article (and in my anecdotal experience, nearly everyone else), Szczepaniak uses MobyGames as a key reference guide for checking game and individual developer credits. He says its quick cross-referencing capabilities are invaluable for research, and it’s been making great strides with both listing kanji for Japanese names and disentangling different people with the same name.

But it’s an incredibly complex problem. Any fully-accurate staff crediting system for Japanese games, Szczepaniak argues, needs to have support for native kanji, phonetic hiragana and furigana (phonetic symbols that appear above kanji), and correct romanizations of these symbols, plus a means of differentiating between first and family names (in his book, Szczepaniak chose to put surnames in ALL CAPS) — as Japanese convention puts the surname first whereas Western convention is to put it last, but neither culture is always consistent.

Szczepaniak points to Naoto Ohshima as an example of problems with naming conventions. “There’s actually three people with the same phonetically pronounced name, all in the games industry, who all worked on different series at different companies,” he explains. “The Sega guy [who designed Sonic], another at ASCII who worked on the Wizardry series, and a graphics guy at Konami who worked on Silent Hill. And for a very long time a lot of websites mixed up the Sega and Konami, thinking they were the same person.”

Even Sega-16, one of the leading sources on all things Sega. This then had knock-on consequences. The misattribution spread to Wikipedia and then across the Internet.

“This misattribution is due to lack of consistency with regards to listing kanji for non-English names,” says Szczepaniak. “All three men have the same phonetic name, ‘Naoto Ohshima,’ but the OHSHIMA part uses different kanji for each of them — that is, different Japanese symbols, which have different pictographic meanings, but all sound exactly the same.”

It gets more confusing. “This problem can also be inverted, with different people having exactly the same kanji symbols, but in each case using a different phonetic pronunciation,” says Szczepaniak. Shigeru Miyamoto, for instance, was miscredited as Shigeru Miyahon in early NES games. And Szczepaniak adds that even Japanese people find this pronunciation issue confusing — to the point where many business cards use hiragana to explicitly state the pronunciation of someone’s name, and at least one developer, Masatoshi Mitori of Human Entertainment, asks that the kanji for his surname not be listed because his family name uses archaic symbols that nobody recognizes.

Then you have the lack of gendered pronouns in Japanese conversation, which means interviews that mention a colleague named “Suzuki-san” could be referring to a man or a woman with the surname Suzuki — and if it’s an archived interview then you can’t necessarily just ask for clarification. As if that wasn’t enough complexity, Japanese credits also have sometimes had nicknames in lieu of real names in them.

Szczepaniak explains that this was not always a case of programmers trying to be cool. Sometimes the publisher ordered it. “Sega was especially notorious for this, and Tecmo as well,” he says. “The reason was to ‘prevent headhunting,’ since companies were terrified that skilled programmers would be snatched up by rivals, and also to prevent later copyright claims for work they had done. Naoto Ohshima said Sega wouldn’t allow staff to attribute their real name since it meant Sega had a stronger hold over the rights to any work created in-house.”

The failure of credits

The reality is that credits, even as a snapshot, could never properly encapsulate the messiness of games history — the complicated power dynamics that form within companies and teams and between individuals, as well as the collaborative nature of the medium and the vast formal and informal support structures that lie beneath each company and project.

Roles are often fluid or informal. One person might start out on programming but finish as a writer or composer, or something else. When I was researching my book, The Secret History of Mac Gaming, I learned that the final design of the very first Mac game, Alice aka Through the Looking Glass, owed as much to the informal requests and complaints of Macintosh marketing rep Joanna Hoffman (who was the best player in the office) as to the work of its creator Steve Capps.

Similarly, Salvador gives an example where the de facto director of 1994 game Millennium Auction “was actually the company’s vice president of business development, and they only received special thanks in the credits.”

Nooney says that informal cross-pollination of roles was common at Sierra, too, whereby people with specific titles pitched in with work on other aspects of a game but weren’t credited for that additional labor due to interpersonal politics.

This can go both ways. People might get a “thanks” credit for non-development labor, or perhaps benefit from a role title that oversells their actual contribution, then try to leverage that to get ahead in their career. Veteran developer Noah Falstein has come across the full spectrum of crediting issues during his 30-plus years in games, and he says he even once received a resumé from someone who said they’d worked on Sinistar — an arcade game project led and co-designed by Falstein.

“I didn’t recognize his name,” says Falstein. “I asked others I knew who had been at the company at the time, and it turned out he had helped load the games onto trucks, so technically it was correct, but had nothing to do with the role he was applying for.”

The truth of the matter is as Maher says, sadly, that because of their inconsistencies and lack of standardization across the breadth of games history, credits must be looked at skeptically. They are a wonderful resource, no matter what, but their failures to properly document the history of labor perhaps reveal a need for something more than just credits as a high-level document record.

“It would certainly be interesting, and helpful for future historians, for companies to credit the entirety of their staff,” says Nooney. “But I think a more provocative way to think about this issue is to recognize the limitations of the ‘authorship model’ as a basis for historical research on games. What else is worth knowing about the game industry beside who worked on a game?”

For Nooney — and indeed for anyone else doing macro-level histories of the different parts of the industry — internal organizational charts are often more valuable than credits because they provide insight into company-wide power relations. More valuable still, she says, is documentation of large corporate or economic events such as mergers, buyouts, layoffs, key hiring decisions that trigger internal re-organization, stock market crashes, and IPOs.

“We tend to miss this critical historical phenomena when we look at the game as our primary source of knowledge about the industry,” she concludes.

In short: Credits matter, and we need to get them right, but if we want to have a good understanding of the history of this medium, and the industries built around it, they’re actually just the tip of the iceberg. We need to do better, across the board, at documenting how we make and sell games.

(source:gamasutra.com )