长篇探讨:饱和的游戏市场下开发者的现状及对策

长篇探讨:饱和的游戏市场下开发者的现状及对策

原作者:Steven Wright 译者:Vivian Xue

“我不建议人们在这些日子里辞掉自己的日常工作,”豪赫·巴科(Jordi de Paco)深深地叹息。

在这变化无常的独立游戏开发领域里,巴科已不是初来乍到者。多年来他参与制作了数十个游戏原型,许多都已在市场上发行。尽管经历了事业上的起起落落,但巴科认为2018年对小团队来说是最具挑战性的一年。

“人人都可以开发游戏,但要面对现实。……曾经你可以做人们从未见过的东西,或者借鉴人们熟悉的游戏并把它做得足够好。但如今你必须创新,并且保证游戏的质量上乘。”

巴科说,他们的工作室Deconstructeam在2014年发行了第一款游戏Gods Will Be Watching,游戏在预售阶段就为他们赚取了利润。而他们的最新作品,2018年1月上线的赛博朋克风格的冒险游戏The Red Strings Club,尽管在推特上获得了无数好评,但游戏直到最近才开始盈利,距离发行日已经过去好几个月了。

然而这种成功的例子只是少数。

同许多游戏开发者一样,巴科目睹了如滚雪球一般日益膨胀的游戏市场,Steam就是其中之一,他感到自己的生计受到了威胁。“如果我们在今天发行Gods Will Be Watching,肯定会失败,”他说道,“过去Steam一周上线20个游戏,如今是一天20个。”

据巴科估计,在他的家乡西班牙遍布着数百个新兴的独立工作室,但其中只有10个通过他们的游戏获得了可观的利润。他提到开发者们在通讯软件Telegram上建的一个私人讨论群组,其中尽显了追逐梦想的艰辛。

“基本上人们在讨论组里抱怨着成功的不易,羡慕其他的开发者,排解失落,”巴科说,“我所了解的西班牙开发者们都在担忧这个问题。当他们发行了一款游戏,能在Steam上卖出500份就已经很幸运了。”

这个讨论组的名称已说明了一切。他们把它称作“独立游戏末日”(indiepocalypse)。

饱和的游戏市场

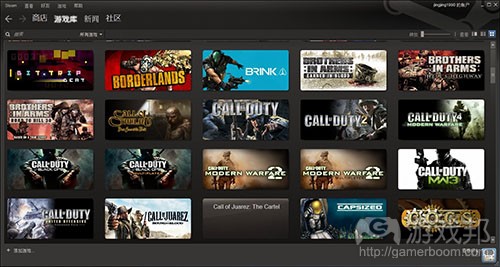

过去十年来,市场上的电子游戏数量呈指数式增长。Steam从一个默默无闻的平台发展成一家资本巨头,汇集了所有的PC游戏,同时任天堂等主机游戏商店紧随其后。夹在《刺客信条》、《使命召唤》等热门的大型系列游戏中,开发者往往感到自己很难有出头之日。Steam上独立游戏数量的成倍增长加剧了竞争,形势对开发者来说越来越不利。

随着大量游戏涌入,Steam平台已然成为一片汪洋,自2014年起至今,平台游戏数量几乎每年翻番——2014年1772个,2015年2964个,2016年4207个,2017年7672个。SteamSpy利用Steam公开数据估算了超过6000个游戏到目前为止的销售情况,根据平台创始人谢尔盖(Sergey Galyonkin),这些游戏大部分销量都在500份以下。

2017年夏天时,任天堂Switch商店每周最多新增5-6款游戏,根据Eurogamer的消息,如今这个数字是原来的四倍甚至五倍,开发者们纷纷渴望抓住这个新平台机会获得销量。

手游市场的形势甚至更加严峻。经历了年复一年史无前例的增长后,苹果商店市场变得拥挤不堪,分析数据显示2017年的新增应用数量减少了将近30%。而管理相对松散的谷歌商店未受到影响,仍以每年17%的速度增长——可能是苹果日益严苛的审核条款带来的副效应。虽然数字缩水,但两大平台上每天诞生的新应用数量仍然达到几百甚至几千个。

随着各大平台游戏数量与日俱增,开发者们不得不承认,拥挤的市场对处于各个发展阶段的开发者来说都会产生负面影响,小到在车库追梦的Solo开发者,大到3A开发商。那些出于爱好制作独立游戏的开发者如果暂时没法实现理想,大不了回去干他们的本职工作,可是如今游戏的制作成本急剧攀升,这意味着对于很多的工作室来说,一旦失败,可能就要面临裁员或解散了。

“如今的市场和我当初开始做游戏时大不相同了,”id Software的前董事兼CEO托德·赫伦希德(Todd Hollenshead)说,id Software是许多知名射击游戏的开发商。最近这位CEO辞职加入了独立工作室Nerve Software。“现如今,像育碧这样的大型发行商对那些销量只有几百万(《毁灭战士》和《雷神之锤》都未达到)的游戏根本不屑一顾。我是id公司的第13个入职员工,Nerve的第10个员工。成功的可能性大不相同了。如今你没有一两百个员工,做不出能让这些家伙改变主意的游戏。成本是个天文数字。”

意识到这些变化后,一些工作室制定了新颖的战略以求从同行中脱颖而出,比如采用非传统营销方式,或者直接借助如今有声望的游戏媒体宣传游戏。一些工作室选择继续呆在舒适区中,持续地创作并尽可能同知名的发行商保持密切联系。但还有一些因为惧怕财务失败,采取了较为严厉的措施。

工作室转型

如今无论做哪种游戏,你都会发现竞争者在不断增加,因此一些做相对冷门类型起家的工作室发现自己只好快马加鞭地追赶流行趋势,渴望挤入下一个热门。不过,尽管做时下热门的类型游戏的确更能迎合主播和其它名人的胃口,但这样的转型会为新兴的开发者以及老开发商带来一系列危害。

当芬兰工作室Housemarque 2017年在Steam上发行双摇杆射击游戏《死亡机器》时,他们并不期望游戏能马上赚到钱。但即便已经抱着这么低的期待,工作室还是为结果感到震惊。凭借着代表作《光电战机》,他们觉得自己似乎已经在Steam上树立了品牌,然而结果不尽人意。当销量最终有所起色时,Housemarque却拒绝讨论相关的细节,但是从SteamSpy和最近泄出的数据来看,这款游戏2018年夏季的销量略低于10万份。工作室情绪悲观,负责发行的主管迈克尔·哈维里(Mikael Haveri)称这是一次“灾难性”的发行。

“结果令我们很震惊,”他说,“目前我们必须要恢复清醒,思考一些别的东西。”

“从某种程度上说,我们的制作是盲目的,”他说,“当我们2017年开始做这款游戏时,我们丝毫没考虑过它的商业潜力。我们甚至不知道如何说服开发商。因此,我们只考虑了游戏的艺术性。这是第一个真正由我们创造、属于我们的IP,我们以往做的游戏IP通常由发行商持有,因此我们认为这是一个跳过中间商的机会,为我们自己做东西,顺便从中赚点钱。”

在哈维里看来,2017年前的Housemarque从不考虑什么宏伟战略,一心只为做他们热爱的摇杆射击游戏。正是抱着这种心态,他们做了《死亡机器》,希望它能成为比《光电战机》更伟大的游戏,就像当初《光电战机》的目标是超越《守卫者》一样。尽管工作室成功地抓住了街机游戏的精髓——甚至请了双摇杆游戏之父尤金·贾维斯(Eugene Jarvis)当设计顾问——由于市场上这种风格类型的高质量游戏实在太多,虽然Housemarque成功让老树开新花,但结果不足以支撑他们这种规模的工作室。

游戏发行四个月后商业表现依旧不乐观,出人意料的是CEO伊拉里·库伊蒂宁(Ilari Kuittinen)在工作室官网上发布了一则题为“街机已死”的通告,宣布街机游戏的销量无法支撑这个中型的工作室的运作。尽管哈维里认为这篇通告有点标题党,但他认为这是公司大胆的转型的第一步,未来公司将采取更温和的策略,比如在发行前先吸引主播和其它有影响力的媒体,以及对每一款游戏的机制给出明确独特的定义,而非列出一长串模糊的想法。

公开宣布脱离街机游戏开发后,Housemarque团队将重点转向一款全新的动作游戏:即将到来的《风暴潜行者》(Stormdivers),这是一款快节奏多人对战第三人称射击游戏,他们希望通过这款游戏绝佳的环境效果挑战日益庞大的吃鸡游戏。尽管哈维里热情支持这种迎合市场的全新策略,但他也承认打入几近饱和的射击游戏市场仍然是个冒险的想法,尤其是Epic《堡垒之夜》和暴雪的《守望先锋》等热门大作已经占领了市场。

这种先寻找潜在市场再创作游戏的想法得到了开发商Dodge Roll的认同,他们的游戏《挺进地牢》(Enter the Gungeon)是一款休闲、操作频繁并具有一定难度的Roguelike游戏,受《以撒的结合》启发制作而成。尽管游戏总监戴夫·克鲁克斯(Dave Crooks)非常庆幸游戏获得了百万销量,但他说这款从头虐到尾的游戏并不是团队一开始想做的类型——工作室的四个人当初被EA解聘后,他们本来商量着做一款像麦克米伦(McMillen)的《超级食肉男孩》那样的传统平台游戏。

“这一切都从给游戏起名字取乐开始,”他说,“后来有一次我们认真地思考后,突然觉得它似乎是个好主意,并且比平台游戏更赚钱。我们真的很喜爱平台游戏,比起《挺进地牢》,平台游戏更加吸引我。但当我们开始设计时,我们想到‘天,要怎么做出一个超越《超级食肉男孩》的游戏?他们有350个关卡。你怎么跟他们比?’《蔚蓝》(Celeste)是做到了,但他们花了好一段时间,不是吗?”

为直播而生的游戏

这不是说《挺进地牢》还没发行就获得了万众瞩目,虽然这是游戏的发行商Devolver所希望的。事实上在克鲁克斯看来,《挺进地牢》成功登顶榜首的唯一原因是它吸引了大量直播用户以及大批喜爱挑战高难度和灵巧性的Roguelike游戏粉丝。

“游戏做出来后,我们开始定期和那些以撒的主播进行交流,”克鲁克斯回忆道,“在PAX展上,有人向我走来说道,‘哟,海军上将巴鲁罗告诉我这是PAX展上必玩的游戏。’好吧我只想说,‘谁他妈是海军上将巴鲁罗?’但事实证明他是位很有名的主播。还有一些其他人走过来说,‘人们说这是下一个以撒。’我心想,‘哇,那太棒了!’这甚至改变了我们的游戏开发,以撒的粉丝希望我们在游戏中添加更多可以和枪支互动的物品。我们成功关键是吸引大主播的关注,NorthernLion、Markiplier、Lyric……这些人的影响力之广是我们做什么都无法达到的。如果你正在制作Roguelike或独立游戏,却没有考虑借助直播的力量,那么你需要重新评估您的营销策略。”

目前他们拥有了庞大的资金储备——并且在7月下旬新增了一堆游戏内容和补丁——不过当谈到下一部作品时,Crooks表示,尽管团队已准备好开发新游戏,但这种兴奋背后隐藏着一丝不祥的感觉。他提到了一个和他住在同一个街区的开发者朋友,他痴迷于研究SteamSpy和其他公共数据,试图从中找到适合开发的完美的游戏类型,但由于一直无法确定,再加上市场起起落落、充满了优秀的游戏,所以迟迟未动工。

尽管直播看似是使游戏(至少动作游戏)成功的秘诀,但在的《堡垒之夜》时代,让你的游戏获得主播的青睐是一件困难的事。那些超级热门,碾压市场的游戏——比如当前市场持久力超乎寻常的吃鸡游戏——都像悬在独立开发者头上的无声威胁。。

Devolver的奈杰尔·劳里(Nigel Lowrie)表示,虽然许多业内资深人士和玩家都认为游戏市场是一座有限的金矿,饥饿的消费者愿意在特定的时间段内消费,比如最近这个神作满天飞的假期(《刺客信条:奥赛德》和《荒野大镖客2》相继发行),很明显,过去几年来开发者面临的限制因素不再是金钱,而是时间。在当前市场下,每一款游戏都充满了各色战利品宝箱、庞大的开放世界、大量可选内容,游戏还没上架,一连串新内容补丁已经在路上了。游戏开发者为了争夺全球的关注,似乎比以往任何时候都更加努力地相互打击。

“即便最硬核的玩家一天能玩14个小时,这仍然是一段有限的时间,”他说,“并且如果玩家在《绝地求生》或《堡垒之夜》上花了10个小时,那么留给我们的游戏的时间还能有多少呢?所以发行的时机至关重要,当然,我不认为单人游戏,小众游戏会消失,它们总是有发展的空间。但你要考虑到一点,一旦人们和其它游戏建立了长期的关系(花在你的游戏上的时间就少了)时间是你无法移动的东西。”

“实际上,这种危机实际上比你想象的还要糟糕。因为不仅游戏的数量在增加,人们的实际游戏时长也会缩减。如果有一些人花大量时间打《堡垒之夜》,那么这些人甚至连Steam客户端都不会打开。因此如果你还在抱怨无法让游戏登上Steam首页,那么这将是另一个令你忧虑的问题。”

克鲁克斯回应了这种观点:“有些人做自己的游戏,有些游戏明显面向一个现存市场。说实话,这很可怕。我有一些朋友对于要选择什么类型或项目感到困惑。我们对下一部作品有很多设想,但我们无法拿定主意。获得像《挺进地牢》一样的成功似乎是一个遥远的想法。我们已经不再对此抱有期待了。但愿将来有人会为了Dodge Roll的口碑而来,但从某种程度上说,做独立游戏意味着你不得不忍受一些苦事。”

品牌的效应

为了发挥熟悉品牌的效应,少数独立工作室决定克服困难,向续作不断的3A游戏大厂看齐。最佳例子是Stoic的回合制策略RPG游戏《旗帜的传说》(Banner Saga)三部曲。团队成员说,游戏的成功不是因为其丰富机制,而是其异常强大的剧情,玩家们不断地为这些剧情付费使他们得以在整个行业动荡的时代中维持周期两年的开发工作——即便周遭的环境不断地变化,热门游戏一次次占领市场然后逐渐消失。

“当你找3A游戏公司商讨续作的事时,他们的回应永远是,‘等你们有了这么精良的画面再来吧,’”《旗帜的传说》三部曲发行商Versus Evil的创始人史蒂夫·埃斯卡兰特(Steve Escalante)说,“即使《黑暗之魂》(Dark Souls)也是如此。从第一部到第三部,视觉效果永远是讨论的话题。在这方面,《旗帜的传说》拥有独特的视觉风格,但不同的是,我们讨论的不是如何把续作做的更宏大、更糟糕还是更好,而是剧情的延伸。这是我们讨论的重点。”

“我们认识许多独立开发者朋友,他们发行过一款很棒的游戏,”《旗帜的传说 3》的剧情创作主管亚历克斯·托马斯(Alex Thomas)说道,“当第二款游戏问世时,他们本想依靠上一部作品累积的玩家基础,但玩家们已经离开了。不知出于什么原因,我们的玩家一直都在那里。游戏剧情是我们长尾战略的一部分,人们仍然喜欢这个游戏,并且我们希望他们在未来几年里依然会喜欢它。 ……我无法具体分析玩家离开或是留下的原因是什么;他们可能去打《堡垒之夜》或者被其它游戏吸引走了。“

正如不少工作室所指出的那样,要想充分利用你的品牌效应,一个关键点是通过提供补丁或者免费的新内容来维持游戏文化的影响力,如此你才能获得稳定的年收入以便开发下一部作品——或者,更好的是进入一个新平台,比如去年吸纳了大量顶尖游戏的任天堂的Switch,据开发者们说,这些付出的回报是十分巨大的。

“为此我们得改写游戏的数据储存方式,”Dodge Roll的克鲁克斯说道,“我从未想过我们的游戏会在这个平台上运行,但我们确实这么做了。自Switch宣布发售以来,我们从各个平台上收到的最多的评论是,‘你们的游戏什么时候登陆Switch?’最终它在Switch上的表现非常好。”

尽管如此,一些开发者觉得这股淘金热快要结束了,轻松把钱赚的Switch早期时代已一去不复返,正如《独立游戏大电影》中Steam昔日的辉煌一般。“我们正处于Switch平台大浪淘沙的时代,”《旗帜的传说》制作人泽布·韦斯特(Zeb West)说,“人们进入商店说,‘我玩够了塞尔达和马里奥,我想要更新、更有深度的游戏。’随着平台的转变,机会也在变化。《旗帜的传说 3》也许赶上了这股趋势的末流,但我认为Switch对我们来说仍是个强势的平台。”

任天堂表示,他们将继续把独立游戏视为Switch平台游戏阵容的关键部分,尽管他们认为这应该由玩家和开发者共同来决定。“我们讨论的是一个真正由我们的消费者驱动的过程,他们想要更广泛的内容,而随着这个范围的扩大,最终平台的选择会越来越多,”任天堂发行-开发关系部副总裁史蒂夫·辛格(Steve Singer)说。

但随着流量不断膨胀,一些开发者想知道他们的游戏是否会被埋没在Switch商店里,就像在Steam上一样。尽管Valve推出的“鉴赏家”功能(curators)没能完全消除开发商和玩家对很难找到喜爱游戏的抱怨,但Switch商店对此采取的措施甚至更少。对此辛格表示这是任天堂目前首要考虑的事。

“例如,我们最近更新了Switch系统的商店,在游戏筛选中加入了‘精选’类别(Featured),我们的‘畅销游戏’中也增添了‘所有游戏’和‘Download-only’(只有数字版无实体)两个筛选项。说来有趣,我感觉我们的粉丝也非常擅长寻找那些独特而优质的独立游戏,然后分享给他们的朋友。”

自主营销

游戏行业内不乏因考虑不周而臭名昭著的PR案例,前有育碧寄送包装酷似引爆装置的《看门狗》游戏而惊动警方,后有动视为宣传《使命召唤 12》编造恐怖袭击新闻。但随着过去五年内优秀游戏的频频诞生,独立工作室开始避开轻松的传统公关路线进行特色营销,以求从人群中脱颖而出——之前《比特币之谜》(Montecrypto:The Bitcoin Enigma)的开发商就为第一个通关的玩家提供了一枚真正的比特币。

Landfall就是其中的一个例子:他们一家小型瑞典工作室,以结合了幽默和创新机制的古怪游戏而闻名。虽然他们的单人游戏没能像《迈阿密热线》一样打入Steam的销量榜,但从竞速平台游戏《卡车跑酷》(Clustertruck)到奇葩又欢乐的吃鸡游戏Totally Accurate Battlegrounds(TABG),几乎所有他们的非正统游戏都获得了来自评论家和粉丝的积极评价。

首席运营官彼得·亨利克森(游戏邦注Petter Henriksson)将Landfall的自我营销描述成一个持续且耗时耗力的过程,以至于干扰了工作室的开发进度。例如,他们最初计划在3月内制作出每年一度的愚人节游戏,但开发人员热衷于吃鸡游戏热潮,最终他们几乎日夜不停地工作了将近三个月,终于将制作出了这款“搞笑游戏”。

然而,尽管这款娱乐的TABG成功在一周内吸引了数百万玩家——主要是因为它是免费的——亨利克森承认开发过程让人筋疲力尽。

“去年圣诞节刚结束,我们就在YouTube频道上发布了TABG的新战斗单位,这花了我们很长一段时间,”他说,“制作免费的《卡车跑酷》Alpha测试版也是如此。这是一种很棒的产品营销方式,因为你可以向那些没买抢先体验版的玩家传达游戏的内容,但做这些东西很消耗时间和资金。不过,我认为这才是当下真正酷的做法。只要你喜欢制作游戏,你完全可以通过制作游戏进行营销,并让出版商或者你的核心团队来帮你处理你要做的大部分事情。”

不过,尽管Landfall的营销方法是他们脱颖而出的关键因素,但亨利克森认为该工作室的持续成功主要源于他们愿意在热门的游戏类型上做尝试和突破。“我们在基于物理的动画方面进行了深入的研究,而这是一个几乎未开发的游戏领域,”他说,“一旦我们做出了东西,它会和同类型的其它游戏不一样。比如,如果我们做了一个基于物理的RTS,那么从定义上看,它将是一种全新的游戏。“

尽管Devolver的奈杰尔·劳里承认像他们这样的发行商需要有潜力的新开发商才能继续生存,但他十分赞赏那些进行自我营销的工作室,尤其是当他们凭借自己纯粹的创造力吸引公众目光时。”如果我们要求拿30%的收入,那他们至少需要比自主发行多赚50%。这么说不是在为我们自己开脱什么,而正是由于我们对我们的业务感觉良好,”他说,”你很难说服所有的开发商,发行商也不是什么开发商都愿意合作的。我在游戏开发者大会的演讲中提到过你根本不需要一个发行商,正是出于这个原因。并不是所有人都需要和开发商合作。即使你有一个发行商,作为一名游戏开发者——如今比曾经多多了——你的工作是让玩家对你的游戏产生兴趣,不仅仅是在Steam上浏览你的游戏。你必须找到你的玩家群体并充分利用他们的力量,告诉他们‘这是我正在做的游戏。跟我来吧,顺便告诉你的朋友们。’”

未知的未来

本文提到的所有工作室都各自经历了因游戏泛滥而导致的行业发展的艰辛。但最终,大家达成共识的是:没有人知道要发生什么。

“我遇到过太多我认为保准能成为热门却最终失败的游戏,”Dodge Roll的克鲁克斯说,“每当这种情况发生,我就愈发担忧我的下一部作品也会是这样的结局。我本来要投资他们的,我本来要买下他们两人公司的股份。”

“大家会一起交流,”Stoic的亚历克斯说,“不过从根本上说,没有人知道什么游戏会火、人们想要什么。这就是为什么一些人像玩足球竞猜一样预测Steam上出现的游戏,因为预测什么游戏会走红是一件有趣的事。每个人都在制作自己热衷的游戏并希望自己能成功。 ”

然而,对于Deconstructeam的巴科来说,除了一些市场上难以预见的变化——在这个充满变数的游戏市场上这总是可能发生——他所想到的未来似乎格外残酷:那些出售开发工具的人将榨干所有的利润。

“当我参加西班牙当地的游戏展时,最大的展位是高校的招生展位,每个人都在试图招纳新生。如果我在年轻的时候碰到了他们,估计我会被他们所吸引,成为莘莘学子中的一员,然后背上一大笔债。我去过这些学校演讲,发表过类似‘瞧这位哥们,他在他的房间里做了一个游戏,还在Steam上发行了’的言论,后来我不再这么干了,因为我感觉自己怂恿了很多年轻人去创立公司然后失败。这些学生需要4万美金完成所有的学业。如果你能招到五名这样的学生,就是20万美金,这笔资金相当于在西班牙进行2-3年建模和测试的花销。游戏开发不像科学,更像炼金,而并且他们希望借助我宣传他们的资质。目前西班牙本土有数百个游戏工作室,其中只有大约 10 家在盈利。”

“在西班牙,那些通过做游戏盈利的正是这些学校,而非开发商。后者的投入成本越来越高,但是盈利机会却越来越小。我认为这是我们真正应该担忧的事。“

本文由游戏邦编译,转载请注明来源,或咨询微信zhengjintiao

“I don’t recommend quitting your day job to anyone these days,” says Jordi de Paco with a heavy sigh.

De Paco is no newcomer to the erratic world of independent game development, having worked on dozens of prototypes and multiple commercial releases over the years. But while his career has had ups and downs, he sees 2018 as the most challenging year yet for small teams.

“Everyone can make games, but be realistic. … It used to be that you could do something that nobody had ever seen before, or you could do something familiar really well. Now, it has to be innovative and have incredible quality.”

De Paco says that his studio Deconstructeam managed to make a profit just off the pre-orders for its first game, Gods Will Be Watching, back in 2014. For its latest game, a 2018 cyberpunk adventure called The Red Strings Club — which received floods of enthusiastic tweets and positive reviews — sales have only started to slip into profit now, many months after its release.

And it’s the exception — the game that’s been able to make it work.

Like a lot of game developers, de Paco sees the daily avalanche of games crashing onto online marketplaces such as Steam as a severe threat to his livelihood. “I think that if we released Gods Will Be Watching today, it would’ve failed,” he says, “because it used to be 20 games a week on Steam, and now it’s 20 games a day.”

By de Paco’s count, there are now hundreds of indie studios sprouting up all around his native Spain, and only 10 of them are actively turning a profit off their games. He describes a private developer group chat on the messaging platform Telegram that illustrates the trevails of chasing the misty specter of building your dream game.

“It’s basically a lot of people complaining about not being able to make it, and being envious of other developers and letting their frustrations go,” de Paco says. “All of the developers I know in Spain, it’s something they fear. When they release a game, they sell 500 copies on Steam, if they’re lucky.”

The group’s name says it all. They call it the “indiepocalypse.”

A SATURATED MARKET

Over the past decade and change, the number of video games on the market has increased exponentially. Front and center, Steam has surmounted its humble origins and transformed into a behemoth of capital and the port of call for all of PC gaming. Meanwhile, console storefronts like the Nintendo eShop aren’t far behind. For independent developers struggling for eyeballs against blockbuster mega-franchises like Assassin’s Creed and Call of Duty, it’s easy to feel like the deck is stacked against them from the start. But the exponential growth of indie games on Steam has tightened the vise against them even further, making it harder to stand out in an ever-crowding market.

The weekly trickle of games flowing into Steam has surged into a roaring river, with the number of games on the platform nearly doubling every year from 2014 to now — 1,772 that year, 2,964 in 2015, 4,207 in 2016, and 7,672 in 2017, according to Sergey Galyonkin of SteamSpy, a site that uses a quickly vanishing trove of public data to estimate the sales of games on the platform. So far in 2018, there have been over 6,000 games released on Steam; the majority of them have sold fewer than 500 copies.

Prior to the summer of 2017, the Nintendo Switch’s eShop saw an influx of five or six games a week at most; now, that number has multiplied by a factor of four or even five, according to Eurogamer, as studios hungry for sales seize the opportunity of a fresh platform.

In the mobile market, the situation is even more dire. After years upon years of unprecedented growth, Apple’s App Store market grew so crowded that analysts reported almost a 30 percent decrease in the volume of new submissions in 2017. The less curated Google Play Store experienced no such drop, growing at a rate of 17 percent year-on-year — a possible side effect of Apple’s more aggressive abuse-deterrence policies toward app makers. Even with these deflated numbers, however, both platforms receive hundreds of new arrivals per day, if not thousands.

As the daily deluge of games continues to pour into these disparate storefronts — and many others — developers of all sizes are forced to reckon with the debilitating effect that the crowding shores are having on every level of development, from solo developers building 8-bit dreams in their garages to AAA behemoths cranking away at massive shared worlds. But while enthusiastic hobbyists might simply return to their day jobs if their indie dreams stay unfulfilled, the scale of big-budget games spirals ever skyward, meaning that more and more employees may lose their jobs if the studio’s one big bet doesn’t pan out.

“The market’s hugely different now from when I started,” says Todd Hollenshead, the former president and CEO of the breakthrough shooter factory id Software, who recently joined indie studio Nerve Software. “Now, a big publisher like Ubisoft would look at a game that sells only a couple million units — which is more than what Doom and Quake sold — as something not worth their time. I was the 13th employee at id; I was the 10th employee at Nerve. The possibilities are very different. Today, you can’t make a game that moves the needle for those guys without less than a hundred, 200 people. The costs are just astronomical.”

In the wake of these changes, some studios have developed novel strategies to stand out from the pack, such as directing their own unorthodox marketing campaigns, or targeting their output directly to the current crop of cachet-wielding influencers who blanket the airwaves with gaming content every day. Some cling to the traditional mantra: Stay within your comfort zone, keep up a steady stream of sequels, and stick as close as you can to an established publisher. But others, stung by the fear of financial failure, have taken more drastic measures.

CHANGING GEARS

As competitors spring from the woodwork in every genre, some studios that cut their teeth on less popular genres have found themselves galloping toward more populated pastures, eager to elbow in on the next hot trend. But while it’s certainly easier to whet the appetites of streamers and other notables by capitalizing on the game-of-the-now, such a transition comes with its own set of perils for both freshly minted newcomers and surly veterans alike.

When Finnish studio Housemarque released a twin-stick shooter called Nex Machina into the wilds of Steam in 2017, it didn’t exactly expect the game to to set tills alight. Even with those lowered expectations, however, the team behind the acclaimed defend-’em-up Resogun found itself shocked at the lack of impact that the Housemarque name seemed to have on the droves of consumers scrolling through Steam every day. When the sales numbers finally trickled in — Housemarque declined to discuss specifics for this story, but SteamSpy and this recently patched achievement leak puts the number slightly below 100,000 copies sold as of summer 2018 — the mood was somber, with the studio’s head of publishing, Mikael Haveri, describing it as “devastating.”

“It was a shock,” he says. “We had to come back to our senses and realize that we had to figure out something else at this point.”

“To a certain extent, we were blind jumping in,” he says. “We never really considered the commercial viability of a twin-stick shooter in 2017. We didn’t even know how to start that conversation with a publisher. So, we considered it from a pure artistic perspective. This was the first IP we actually own and created, and the publishers generally hold onto the IPs we work on, so we saw a possible venue to cut out the middleman and do everything for ourselves, and make a little more money in the process.”

Haveri describes the pre-2017 Housemarque as a studio that eschewed grand strategy for the pure impulse of a twitch action fan. True to form, Nex Machina emerged from the company’s long-held desire to create “the ultimate Robotron game,” just like how Resogun aimed to one-up the classic Defender. But while the studio succeeded in capturing the spirit of the arcade — even roping in twin-stick pioneer Eugene Jarvis for the ride — Haveri says that there are simply too many small developers churning out quality games in that style and genre for Housemarque’s neoclassical approach to support a studio of its scale.

Four months after the news of the game’s subpar commercial performance, CEO Ilari Kuittinen published a surprise announcement on Housemarque’s website with a headline that blared the now-infamous phrase “ARCADE IS DEAD,” declaring that the team’s arcade niche had failed to recoup the sales that the mid-sized studio needed to survive. While Haveri describes the provocative post as “a bit of BuzzFeed-y clickbait,” he says that he views the company’s shift in focus as the first step toward a bold new image, bolstered by less radical tactics like capturing the attention of Twitch streamers and other influencers prior to launch, as well as communicating a single unique mechanic that defines a game rather than a laundry list of unclear ideas.

Since Housemarque’s public departure from the jumble of old-school genres that constitute the ever-nebulous “arcade” label, the team has shifted its focus to an entirely new vein of action game: the upcoming Stormdivers, a fast-paced multiplayer third-person shooter that utilizes showstopping environmental effects to shake up the ever-growing battle royale genre. While Haveri is enthused by this market-driven concept, he admits that trying to break into the ultra-saturated competitive shooter field, where titans like Epic’s Fortnite and Blizzard’s Overwatch continue to eclipse the spotlight, remains a risky proposition.

This sense of developing a potential market first and letting the ideas follow is echoed by Dodge Roll, the developers behind Enter the Gungeon, a light-hearted but wrist-snappingly difficult roguelite that takes a songbook’s worth of cues from Edmund McMillen’s The Binding of Isaac. While game director Dave Crooks is thankful for the millions of sales, he says that the fiendish top-down Gungeon isn’t necessarily in the genre that the four-man team first set out to make — when they got laid off from EA Mythic following a studio closure, they had discussed making a more traditional platformer in the vein of McMillen’s other breakout hit, Super Meat Boy.

“It started as a joke name to a game,” he says. “And then once we thought about it, it suddenly seemed like a good idea, and a better way to make money than a platformer. We really like platformers, and I would personally play a platformer over something like Gungeon on the store, but when we sat down to design it, we thought, ‘Man, how do you even make a platformer after Super Meat Boy? They have 350 levels. How did you even compete with that?’ Well, it turns out that was Celeste, but it took awhile to figure that out, huh?”

DESIGNING FOR THE STREAMER CROWD

This isn’t to say Gungeon garnered the sort of pre-release hype that the game’s publisher, Devolver, expected. To Crooks’ mind, the only reason that Gungeon managed to rocket its way to the top of the charts was the sudden realization that streamers were poised to embrace the game with unrivaled vigor, along with the legions of roguelike fans slavering for a stiff challenge of dexterity and wit.

“Once the game was out there, we started talking to the bigger Isaac streamers pretty regularly,” recalls Crooks. “Somebody would walk up to me at PAX and say, ‘Yo, Admiral Bahroo told me that this is the game to play at PAX.’ Well, to me, I just said, ‘Who the fuck is Admiral Bahroo?’ But it turns out that he’s this huge streamer. And someone else walks up and says, ‘People are calling this the next Isaac.’ And I thought, ‘Well, that’d be great!’ It even changed how we developed the game. … The Isaac fans wanted more items to interact with the crazy guns we’d added to the game. The single most critical component of our success was catching the attention of big streamers. That’s what made our game. NorthernLion picking it up for as long as he did, Markiplier, Lyric — the reach of those people is far beyond anything else we could really do. If you’re making a roguelike or an indie game, and you’re not thinking about how streamers can help you, then you need to reevaluate your marketing strategy.”

Still, even with that colossal mound of cash banked — and a heap of content added to the game with a free patch in late July — when it comes to Dodge Roll’s sophomore effort, Crooks says that while the team is ready to work on something fresh, behind the excitement lurks a sense of impending doom and gloom. He relates a story of a developer friend of his who lives just down the block who obsessively combs through SteamSpy and other public data, trying to pinpoint the perfect genre to strike, but remains paralyzed by a lurking sense of uncertainty, the buck and jolt of a market stuffed to the gills with excellent games.

But while streamers might seem like a silver bullet of sorts, at least in the action genre, it can be difficult to get onto a streamer’s docket in the first place in the age of Fortnite. The specter of hyper-popular, market-crunching games — such as the current battle royale craze, which has displayed more endurance than the usual gaming fads — hangs like a silent threat over the heads of indie developers everywhere.

Devolver’s Nigel Lowrie says that although many industry veterans and gamers alike think of the gaming market as a finite amount of money that hungry consumers are willing to spend in a given time period — say, this bloody holiday season, which is particularly awash with high-profile franchises that must duke it out, such as Assassin’s Creed and Red Dead Redemption — in the past few years, it’s become apparent that the limiting factor isn’t measured in dollars, but hours. In a climate where every game is stuffed to the gills with five tiers of colored loot, massive open worlds, reams of optional content and a dozen content patches lurking on the schedule before the core package even hits store shelves, it seems that game developers are battering each other harder than ever before to compete for the attention of games worldwide.

“Even if the most hardcore gamer plays 14 hours a day, that’s still a finite amount of time,” he says. “And if you’re spending 10 of those in a PUBG, or a Fortnite, what does that leave for the rest of us? It’s true that timing of release is critical, sure, and I don’t think that single-player, smaller-scope games are going to go away; there’s always going to be room for that. But time is something that you really can’t move, and you have to account for that when people move into these long-term relationships with games.

“The crunch is actually worse than you might think, because it’s not just the number of games that are increasing; the number of actual gaming hours out there could be shrinking, too. If some number of people are playing Fortnite for some massive amount of time, well, that’s a lot of people who aren’t even opening their Steam client. If you’re a developer out there complaining that you can’t get your game on the front page of Steam, well, this is a whole new thing you have to worry about.”

Crooks echoes this ambiguity: “Some people do their own thing, and some games come out that are clearly pointed at an existing market. To be honest, it’s scary. I have some friends who aren’t doing that well, or are obsessing over what genre or project to pick. We have a bunch of ideas for Game 2, but we really have no idea. The thought that we could ever capture the success of Gungeon again seems like such a long shot. We’ve already resigned ourselves to never expect anything like that. Hopefully some people will come over for the name Dodge Roll, but at some point, you just got to swallow that pill if you decide to make indie games.”

WHAT’S IN A NAME

Of course, in terms of relying on a familiar brand, a scant few indie franchises have managed to beat the odds and carve out a scheme more akin to the endless sequel-izing of the AAA games machine. Perhaps the best example remains Stoic’s Banner Saga trilogy. While the small team behind the turn-based series has managed to keep the candle burning throughout a turbulent era of the industry, team members say that they owe their success not to the game’s wealth of mechanics, but its unusually strong narrative, which keeps players invested through each two-year development cycle — even as the industry changes around them, and two or three Next Big Things each dominate the scene and fade away.

“When you have the sequel conversation with triple-A games, it’s always, ‘Wait till you see these updated graphics,’” says Steve Escalante, the founder of Versus Evil, the publisher of the trilogy. “That’s the case even with Dark Souls. From 1 to 3, there’s a visual conversation there. Banner Saga paved the way for this unique visual style in this space, but it’s this extension of this amazing story, as opposed to doing it bigger, badder or better. That’s our sequel conversation.”

“I know a lot of indie developers that are friends of ours who put out a game that did great,” says Alex Thomas, the lead writer on The Banner Saga 3. “But the second game comes out, and they expect it to feed off the community from the first game, but the players have moved on. For us, for whatever reason, they haven’t. The story is part of our long tail, people are still enjoying the game, and we hope they enjoy it from years to come. … I can’t break down why players come back or don’t come back; they’re on Fortnite or something else.”

As several studios note, a key part of leveraging your brand is staying in the cultural conversation long enough through patches or free updates so that you can harness years of continuing revenue to fund your next project — or, better yet, justify entry into a fresh market, like the Nintendo Switch, which has experienced a rapid influx of top-notch games in the past year. According to these developers, the return can be massive — and overwhelming.

“We had to rewrite how the game stores all its data,” says Dodge Roll’s Crooks. “I never thought our game would run on that thing, but it does. The most common remark we got on all of our platforms since the announce of the Switch was, ‘When’s it coming to Switch?’ It did really well.”

Still, some developers feel that the gold rush is at its end, and the easy money of the early Switch era is spent, much like the glory days of Steam that inspired Indie Game: The Movie. “We were in the middle of the big wave on Switch,” says Zeb West, producer at Stoic. “People were going to the store and saying, ‘I’m done with Zelda and Mario. I want another game for this. I’m digging deeper.’ As the platforms change, the opportunity changes. We’re maybe on the tail end of it with Saga 3, but I think it’ll continue to be a strong platform for us.”

For its part, Nintendo says it continues to view indies as a key part of the Switch’s lineup of games, though the company casts it as a groundswell led by players and developers alike. “We’re talking about a process that’s really being driven by our consumers, who want a wide range of content, and as that range grows, ultimately have more to choose from,” says Steve Singer, vice president of publisher and developer relations.

But as the flow continues to swell, some developers wonder if their games will be buried on the Switch eShop, creating the curation problems that Valve faces with Steam. Though Valve’s “curators” program has failed to totally stem the tide of game makers and players alike complaining of issues discovering games that appeal to them, the eShop has even fewer options than that. Singer says that such concerns are “top of mind” for Nintendo.

“For example, we recently updated Nintendo eShop on the Nintendo Switch system to include a ‘Featured’ view, and our ‘Best Sellers’ view now allows customers to sort using ‘All Games’ or ‘Download-Only Games’ filters. Speaking anecdotally, my sense is that our fans are also very good at finding those unique, quality indie experiences, then evangelizing that content to their friends.”

DOING IT YOURSELF

As any industry observer knows, the gaming sphere is notorious for ill-considered PR stunts, from review copies disguised as explosive devices to livetweeting a fictional terrorist attack to promote a new wargame. But as virtual shelves have begun to overflow with great games over the past half-decade, indie studios have begun to eschew the cozy traditional PR route to perform their own marketing in a plea to stand out from the crowd — after all, just look at the indie puzzler that offered a Bitcoin to those who first solved it.

Landfall is one such case: a small Swedish-based studio that’s cultivated a reputation for phenomenally kooky games that strike at the intersection between low comedy and innovative mechanics. And while its individual games haven’t exactly cracked the skybox of Steam in the manner of a Hotline Miami, nearly all of its unorthodox fare, from the high-speed vehicular platformer Clustertruck to the delightfully wonky battle royale parody Totally Accurate Battlegrounds, has garnered positive buzz from critics and fans alike.

Chief operating officer Petter Henriksson describes Landfall’s process of self-marketing as continuous and all-consuming, so much so that it can interfere with the development of the studio’s games. For example, Landfall originally planned to dedicate the month of March to the production of its yearly April Fools joke, but the developers’ love for the battle royale milieu took over, and they ended up working on it for nearly three months, pulling nearly all-day shifts to get the “joke game” just right.

Still, even when it works — as with the legitimately entertaining TABG, which lured in millions of players over a week, largely due to its lack of a price tag — Henriksson admits that the process can be exhausting.

“Last year, right after Christmas, we were posting daily updates on our YouTube channel for new units for Totally Accurate Battle Simulator; it took a huge chunk of time,” he says. “Same thing with making a free alpha for Clustertruck. It’s a great way of promoting a product, because it’s a great way of communicating what the game will be to a customer without Early Access, but you burn time and money on these things. But, for me, I think that’s what really cool about right now. As long as you love making games, you can do marketing through making games, and get around most things you’d need to do through a publisher or such just through your core team.”

Still, although Landfall’s approach to marketing is a key differentiator, Henriksson feels that the studio’s consistent success has mostly come from its willingness to experiment with established genres. “We work really deeply with physics-based animation, and that’s a very unexplored territory of games,” he says. “As soon as we do something, it almost becomes different from other things on its own. Like, if we did a physics-based RTS, for example, that would be fresh by definition.”

Though Nigel Lowrie admits that publishers like Devolver need promising newcomers to survive, he applauds studios that take their promotion into their own hands, especially when they turn heads with sheer inventiveness. “If we’re going to ask for 30 percent of the revenue, then they need to make at least 50 percent more than they would’ve on their own. That’s not just to cover our asses; that’s so we feel good about our business,” he says. “You can’t work on them all, and they don’t all make sense for a publisher. I did a talk at GDC that said you don’t need a fucking publisher, and that’s for that very reason. Not everybody needs to be working with one. … Even when you have a publisher, as a developer — now more than ever — your job is to get people interested in your game, period, not just when scrolling through Steam. You have to find your community and really leverage them and say, ‘This is what I’m doing. Follow me, and tell your friends.’”

THE UNCERTAIN TRUTH

Each of the studios mentioned in this story each has a distinct experience with the travails that the sheer deluge of interactive entertainment has brought onto the industry. But in the end, they all agree on one thing: Nobody knows what’s really going on.

“I’ve seen so many games that I think are surefire massive hits end up failing,” says Dave Crooks, of Dodge Roll. “Every time it happens, I become more and more worried that the next thing I decide to make will go that route. I would’ve bet on these people — I would’ve bought stock in their two-person company.”

“Everybody talks to each other,” says Alex Thomas of Stoic. “The underlying thing is, nobody knows what’s going to hit, what people want. And the boring answer is that nobody really knows at all. That’s why some people play fantasy football with games that come out on Steam, because it’s fun to make a game of guessing what’s going to do well. Everybody just makes the games they’re excited about and hope they hit.”

For Jordi de Paco of Deconstructeam, however, barring some unforeseen change in the market — always a possibility in the quick-fire world of games — the future he envisions seems particularly trying: one where those who sell the tools are the ones who extract all the profit.

“When I go to games events here in Spain, the biggest stands are the ones for the universities, and everybody is trying to recruit students. If they were there back when I was younger, I would’ve joined them, and gone into debt. I’ve been to those universities to give speeches, like, ‘Look at this guy, who just in his room made a game and made it on Steam.’ I stopped doing that, because I felt like I was pushing a lot of young people to build companies and fail. These students have to pay $40,000 to go through all the studies. If you put five of those students together, that’s $200,000, and that’s a budget of 2-3 years here in Spain to prototype and experiment. Game development is an alchemy, not a science, and they want to use me as a poster boy to sell their degrees. There are now hundreds of dev studios here in Spain, and about around 10 of them are profitable.”

“In Spain, the ones who are making money in video games are the schools, not the developers. They’re feeding the machine. I think it’s something to worry about.”(source:Polygon )