教育类电子游戏的兴盛与衰败

作者:Bryant Francis

从20世纪80年代末到20世纪90年代,主机游戏和计算机游戏一直是两个非常分裂的市场,其中一些工作室更是在蓬勃发展的个人计算机市场上创建了一个轰动一时的“帝国”:教育类电子游戏。

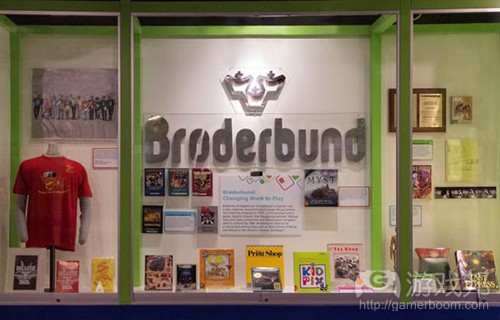

包括Broderbund,The Learning Company,The Minnesota Educational Computing Consortium都拥有一些具有百万销量的游戏,如《The Logical Journey of the Zoombinis》,《神偷之门》和《俄勒冈之旅》。

尽管许多这个时代的游戏系列都继续引起了巨大轰动,但却很少有游戏能够宣称自己与这些游戏拥有同样高的价值:它们因为提供了明确,具有社交性,且能够教授学生有关数学,历史,地理和艺术等内容而得到广泛的认可。根据你的年龄,你可能会有在教室里使用Apple II玩这些游戏的经历。如果你在这个时代有自己的小孩,你可能会记得自己曾经每年花费200至300美元在家庭PC上安装这些售价40美元的游戏并希望它们能够帮助你的孩子提高学习水平。

而在1999年之后,这种局面发生了变化。

尽管一些品牌在全新开发团队的支撑下又继续艰难地发展了几年,但是在CD-ROM发行商Softky收购了The Learning Company并使用了它的名字,然后以同样的方式又收购了Broderbund后,90年代的教育游戏发展热潮开始陷入停滞状态。之后Mattel又收购了The Learning Company,而在他们发布一些损失后,该公司又再次易主卖给了Gores Technology Group,最终,该公司被分解并归给了育碧和Riverdeep,于此同时它不得不裁掉那些曾经创造了有趣的游戏玩法与高质量教育内容结合体的雇员们。

这些游戏影响了一代人。游戏中的“课程”不仅激励了学生深入了解有关数学,地理或历史等内容,同时在某种程度上也让他们产生了学习编程或游戏开发的想法。也是因为这些游戏推动了许多学生成为了今天游戏产业中的一份子,而如今像《Zoombinis》等游戏也凭借Kickstarter重新回到我们面前。所以我们可以从那个时代的游戏中学到什么并将其应用到现在的游戏产业中?

什么内容对教育有帮助?

对于那些想要延续那个时代内容的人来说,Broderbund和The Learning Company的瓦解是教育类电子游戏的巨大损失。设计师James Portnow便始终拥护当代游戏具有教育的可能性。他强调在这个时代,教育专家和游戏设计专家应该结合在一起去创造那些并不只是复制教科书内容的游戏。他认为如果缺少这种联系,教育游戏便不能到达它们过去所创造的那一高度。

他说道:“现在让我们将教育游戏和娱乐游戏当成两个不同的产业。我们将进行不同的交谈,浏览不同的网站,并与不同的发行商进行合作。而如果我们希望看到教育游戏发挥自己的真正潜能,这种情况就必须发生改变。”

让我们回去与那个时代的开发者和执行官们交谈,还有许多来自那个时代的经验教训能够推动着这个产业取得成功。首先便是:当开发者拥有机会能够最大限度发挥创造性,并且他们身处一个非常健康的环境下,那么寓教于乐型游戏便可能发挥自己的最大潜能。

Unity现在的研究和开发工程师Peter Feese曾经是Edmark(游戏邦注:这是一家专注于为学生开发游戏的教育软件公司)的程序员。

他参与的第一款游戏《Thinkin’ Things》仍然是他最喜欢的那个时代的游戏。对于Freese来说,这款游戏之所以比其它游戏有趣是因为它是一个包含许多全新设计师,并且这些设计师在此投入了比一个更高级项目更多价值的创造的试验型项目。Freese说道:“我们的配合非常棒,同时我们也拥有许多自由能够决定我们在游戏中该做些什么。”

Laurie Pedersen(之前在Broderbund作为教育部开发总监时叫做Laurie Strand)回忆起过去12至14个月的开发周期,那时候他们会花3至6个月时间去创建游戏原型。而对于像《The Logical Journey of the Zoombinis》等广受好评的游戏,他们会与开发搭档,如名为TERC的剑桥智囊团合作,并获得来自孩子们的反馈(游戏邦注:通常都是公司雇员的孩子们),同时还将这些反馈用于完善原型。

Pedersen解释道:“TERC本身便包含测试功能。之后我们会聚集在一起并判断内容是否可行,他们会测试不同的游戏玩法,我们的动画团队也会调整角色的外观。”

她补充道:“这是一个较长的过程。而这也是在今天我们不可能做到的,因为现在你可能需要在不到30天时间内便创造出一款应用。”

Pedersen同样也重复了Portnow关于共同参加会议的评价,她回想起Broderbund参加了全国教育计算大会以及其它在波士顿和旧金山举办的教育大会,并认可了这对于推动游戏销售并分享有关设计信息的必要性。

而所有的这些都是发生在一个乌托邦式的工作环境中。Michelle Bushneff(在Broderbund工作期间她从美术师变成了艺术总监后又变成了成了副经理)是这么描述他们的工作室,“我在这里真正感受到了生活该是怎样的,因为这就像是一家家庭运营的公司。我们公司允许员工带狗,并且我们也为动画师们提供了在线绘画课程,甚至在Pixar诞生初期还有一些来自Pixar的工作人员跑来与我们交谈。”

我们很少会有加班的情况。并且所有人都非常信赖自己所分配到的任务。我们的整个销售团队中包含了一些之前当过老师的人,他们与许多学校合作希望将数更多Broderbund游戏带到课堂上,而这些开支也是公司能够负担得起的。这是一个非常正面的环境,它并不会影响到Bushneff及其Broderbund中的同事之后的职业生涯。在各自去追寻自己的其它目标后他们仍保持着密切联系,并且每隔几年他们都会在创始人的家里聚会。

“无形之手”

安全的现金流,优秀的人才,相互协作的空间,扁平的等级制度以及长期的原型创建过程等都是任何工作室的理想条件,但这也还是不能保证长久的成功。

见证了教育类游戏的起起落落,并与自己在Edmark的程序员搭档一起致力于像《Blood》等游戏的Freese对于该类型游戏最大的开发商的衰败并不感到惊讶,反而他更惊讶于之后未曾再出现其它替代者,因为他也有自己的小孩。随着90年代的过去,当他想要购买高质量的教育游戏时,他却发现自己很难再找到适合的游戏。

Freese解释道:“不管是公司改变,各种起起落落,成功与失败,这些都是很正常的事,但总是会出现一些新事物去替代它们。”

当进一步着眼于The Learning Company和Broderbund的衰败时,我们会发现这主要是因为孤立的环境所造就的,而这也是不断改变的市场的一个通病,还有部分的改变也是源于他们的收购者Softkey。Softkey的销售模式完全改变了Broderbund和The Learning Company之前创造出最佳游戏所使用的高成本和高奖励性模式。

Ken Goldstein(曾经是Broderbund的娱乐和教育部副总监,而现在是一名作家也是初创公司顾问)表示,伴随着游戏的高销量以及CD-ROM的盛行,Softkey引进的全新定价模式彻底改变了Broderbund的业务方式。

Goldstein说道:“在90年代,即当CD-ROM开始盛行时,第一个找到我们的便是Price Costco,他们想要在每个店面出售我们的游戏。于是我们便从制作10万份游戏变成制作100万份的游戏,并且在一年内我们90%的业务都是面向超级卖场。”

“我们曾经将所有的游戏堆积在停车场,并祈祷着千万别下雨,因为我们的仓库已经没有足够空间放这些游戏了!”

“如果你使用的是49.95美元至59.99美元的零售价,你便不可能卖出100万份的游戏。所以你需要将价格降至29.95美元,这意味着批发价为22至23美元。随后更有竞争力的零售价又降至了19.95美元,而批发价也降到了12美元。”

伴随着价格的下降,利润也跟着下降了。Broderbund董事会决定将公司的整体业务转向大规模的零售业,并且该公司也发现自己正与Softkey等以极低价格(9.95美元)出售CD-ROM的软件开发商们展开激烈的竞争,这意味着他们每出售一份游戏只能赚到1至2美元的利润,而基于这样的利润,他们便很难再资助长期的原型创建与高价值游戏的创造。

Softkey以及其它以低价出售CD-ROM的开发商所主张的全新定价模式破坏了寓教于乐产品制作的经济可行性。显然Goldstein因为这样的并购感到难过,但在17年后的今天,他也表示这是无法改变的情况。对于他来说,Broderbund的定价模式是基于“消费者–产品–利润”的原理,在这里优秀的人才将创造能够带来利润的优秀产品,但一旦出现并购,这一原理将被彻底颠覆,而之后,作为The Learning Company一部分的Broderbund又被卖给了Mattel。

Portnow强调,随着巨大改变的出现,Mattel只能想到一种方法便是去利用The Learning Company的数百万美元教育资源—-即开发一款授权的芭比娃娃游戏并在环城百货中出售这款游戏。

毕业

但即使Mattel不知道他们手上握着的到底是什么,全世界也能告诉他们答案。

不管何时当Goldstein谈论到他在Broderbund的日子,他都会想起为什么Broderbund的工作如此重要:“当有人看到我的履历表中有Broderbund所创造的游戏时,他们都会跟我说是这些游戏将他们带到了软件工程领域。还有什么比这个更让人感动的呢?”

Freese在Edmark的工作影响着他之后的游戏开发工作,并不断提醒着他现代游戏中一些功能是源于那些教授玩家数学和阅读的游戏。

Freese说道:“我学到了许多有关呈现内容给那些不是阅读者的用户。我始终牢记自己是什么时候在制作一款游戏,并且如何设计游戏界面。我所坚信的一个理论便是,如果你必须向某人解释你做的是什么的话,那便说明你做错了。”

非盈利的TERC通过在Kickstarter上筹集到101716美元而复活了《Zoombinis》,来自西班牙或非洲裔美国人的游戏开发者谈到了《The Chief》的Carmen Sandiego和Lynne Thigpen角色是如何帮助他们始终保留对于教育的兴趣,而教育也始终是游戏产业追逐多样化表现的早前里程碑。

90年代教育游戏所撒下的种子在多年来仍持续影响着游戏产业,它们的经验教训对于那些面向娱乐领域的设计师来说仍然非常重要。基于强大的数字分销模式以及那些已经拥有自己的小孩,消息灵通且具有怀旧情结的消费者基础,或许在不远的将来我们便能看到这类型游戏重现江湖。

(本文为游戏邦/gamerboom.com编译,拒绝任何不保留版权的转发,如需转载请联系:游戏邦)

Where in the world did blockbuster educational games go?

By Bryant Francis

From the late 1980s through the 1990s, as console games and computer games remained two very separate markets, a handful of studios built a blockbuster empire atop the burgeoning personal computing market: the educational video game.

Broderbund, The Learning Company, and The Minnesota Educational Computing Consortium were selling millions of copies of games including The Logical Journey of the Zoombinis, Where in the World is Carmen Sandiego?, and The Oregon Trail.

While many game series from that era went on to be massive blockbusters, not many could claim the same value these titles did: that they were widely accepted as providing a clear and arguable social good, capable of teaching students about math, history, geography, and the arts. Depending on your age, you might remember playing some of these games on your classroom’s Apple II. If you had kids in that era, you may remember shelling out between $200 to $300 a year for these $40 games on your home PC in the hope yourself that it might help your child’s grades.

But after 1999, it all just suddenly stopped.

Though some of these brands limped along for a few more years under new development teams, the educational game boom of the 90s slowed to a halt after CD-ROM publisher Softkey purchased The Learning Company and adopted its name, then acquired Broderbund in a similar fashion. The new giant known as The Learning Company was bought up by Mattel, but after posting losses even as the sale was ongoing, The Learning Company was sold to Gores Technology Group, then splintered between Ubisoft and Riverdeep, all the while laying off and forcing out the employees who made the secret combination of fun gameplay and quality education possible.

These games had a huge impact on an entire generation. Their lessons inspired students not just to dig deeper into lessons about math, geography, or history, but in some cases to take up programming or game development themselves. With these students now becoming part of the game industry, and titles like Zoombinis making a successful return on Kickstarter, what lessons from the era still apply to the game industry today?

What Worked In Education?

To those working to carry on this era’s legacy, the fracturing of Broderbund and The Learning Company represented a huge loss for the potential of educational video games. Designer James Portnow, who writes for Extra Credits and runs the nonprofit Games for Good, has been championing the educational possibilities for modern games. He notes that this era was the one time that experts in education and experts in game design worked together and produced games that weren’t just re-skinned textbooks. He argues without that connection, educational games can’t reach the same potential they did at their incredible heights.

“Now we think of educational games and entertainment games as two different industries,” he says. “We go to different conventions, read different websites, and work with different publishers. This needs to change if we ever want to see educational games grow into their true potential.”

Going back to speak with developers and executives from this period though, there are other lessons from that time period that drove this cottage industry’s success. The first: the edutainment genre was one that operated at its finest when its developers had both the opportunity to push their creative limits, and a healthy environment in which to do so.

Peter Freese, one of Unity’s current research and development engineers, was a programmer at Edmark, an educational software company specifically developing games for classrooms.

Thinkin’ Things, the first game he was hired to work on, is still his favorite from the era. To Freese, that game stood out from the other titles because it was an experimental project filled with new designers where input from all team members held more value than on a more hierarchical project. “We bonded really well, but we also had a lot of freedom to decide what we were doing in the game,” Freese says.

Laurie Pedersen, known as Laurie Strand during her time with Broderbund as head of development for the education division, recalls that in a 12- to 14-month development cycle, three to six months of that time would be spent building a prototype. And on critically acclaimed titles like The Logical Journey of the Zoombinis, that meant working with their development partner, a Cambridge think tank called TERC, to take feedback from children—often children of company employees—and use it to improve those prototypes.

“TERC was also very very involved in testing on their side as well,” Pedersen explains, “and then we would come together, and say ‘well this didn’t work,’ and they would test different gameplay, our animation team would fine-tune the look of the characters.”

“It was a long process,” she adds. “It’s not something possible in today’s world where you might need to do an app in as little as 30 days.”

Pedersen also echoed to Portnow’s comments about mutual conference attendance, recalling Broderbund’s participation in the National Educational Computing Conference and other educational conferences in Boston and San Francisco being essential both for driving sales and sharing knowledge about the design at hand.

All this took place in a utopian work environment many would consider a work of fiction if it hadn’t actually existed. Michelle Bushneff, who rose from artist to art director to vice president during her time with Broderbund, describes the office as one that “kind of spoiled me over what life would look like, because it was just for the family-owned run company at the time. Dogs were allowed at the office, we had on-site life drawing classes for the animators, and in the early days of Pixar we even had some of the guys from Pixar come in and talk to us.”

Crunch was limited. The mission was something everyone believed in. And with assets like an entire sales force filled with former teachers working with school districts to get millions of copies of Broderbund games into the classrooms, those luxuries were ones the company could afford. It was an environment so positive it didn’t just spoil Bushneff for the rest of her career, but also her fellow Broderbund employees. They’re still close, gathering at the founder’s house every couple of years and keeping in touch even after going their separate ways.

The Invisible Hand Strikes

Secure cash flow, talented staff, collaborative spaces, flat hierarchies that work well with long prototyping periods–all of these conditions would be ideal for any studio, but they still don’t guarantee constant success.

Freese, who watched the edutainment genre rise and fall as he struck out to work on games like Blood with his fellow Edmark programmers, wasn’t so much surprised with how the genre’s biggest developers fell apart, but he was surprised with the fact that nothing came in to replace them, mostly because he had kids of his own. As the 90s passed, when he went shopping for high-quality educational games, what he found was often either inadequate–or just plain nonexistent.

“Companies changed, they had rise and falls, and successes and failures and that kind of thing,” Freese explains. “That was normal, and we expected that to happen, but there weren’t new stars rising to take their place.”

Looking closer at The Learning Company and Broderbund’s collapse, that’s because it wasn’t due to isolated circumstances–it was a symptom of an entire changing market…which changed in part because their purchaser, Softkey. Softkey’s sales model ultimately interfered with the high-cost high-reward model Broderbund and The Learning Company had built their best games on.

Ken Goldstein, now an author and startup consultant, was vice president of entertainment and education at Broderbund and can chart exactly how the pricing models introduced by Softkey, mixed with the huge sales of their games and the CD-ROM boom shifted the entire way Broderbund did business.

“In the 90’s, when CD-ROMs went crazy through the ceiling, the first one who came after us was Price Costco, who asked for a pallet of games for each of their stores,” Goldstein says. “We went from producing 100,000 copies on a run, to 1 million copies on a run, and within one year 90 percent of our business was in big box stores.

(Zoombinis CD case picture credit: The Strong.)

“We used to stack it all up in our parking lot and pray it wouldn’t rain because our warehouse couldn’t hold all the goods!

“When you went from these kinds of volumes the idea of a retail price point like $49.95 to $59.99 doesn’t work if you want to sell through a million copies. You need to sell at $29.95 at retail to hit that goal, which means selling at $22-$23 wholesale. Then competitive retail dropped to $19.95 and wholesale slipped to $12.”

And with dropping prices came dropping margins. With Broderbund’s board pushing to move all of the company’s business into high volume mass retail, the company found itself competing with other software developers, like Softkey, who were selling CD-ROMs at dramatically lower prices as low as $9.95 thanks to mail-in rebates. That meant only $1-$2 profit margins on every individual copy of every game sold, and on such margins, the ability to fund the long prototype times and high production values of Broderbund’s software slid away with every game.

The new pricing model, driven by both Softkey and every other developer in the business selling CD-ROMs at such low prices, destroyed the economic viability of the edutainment production cycle. Goldstein was obviously frustrated with the merger, but 17 years later, he says it’s water under the bridge. To him, the Broderbund model was built on the philosophy of “people–products–profit,” where talented people created good product that drove profit, but once the merger kicked in, that philosophy seemed to flow in reverse, and Broderbund, now part of The Learning Company, was sold to Mattel.

Portnow notes that in the wake of this dramatic change, Mattel could only think of one way to utilize The Learning Company’s multimillion dollar educational resources–developing licensed Barbie games destined for the dollar bin at Circuit City.

Graduation

But even if Mattel didn’t know what it was holding on to, with practically an entire genre of gaming in its hands, the rest of the world did.

Whenever Goldstein gives talks about his time at Broderbund, he has a frequent encounter that reminds him why Broderbund’s work was so important: “When someone sees these Broderbund games in my bio and they tell me that these games were what got them into software engineering…what can warm your heart more than that?”

Freese’s work at Edmark was massively influential in the rest of his game development career, and a reminder that some features in modern-day games have strong roots in games meant to teach math and reading.

“I learned a lot about how to present things to users who are not readers,” Freese says. “I’ve always carried with me the idea that when I’m working on a game, how I design the interface? And one of my philosophies is, if you have to explain to someone what to do, you’ve done it wrong.”

The nonprofit TERC has revived the Zoombinis franchise on Kickstarter to the tune of $101,716, and game developers of Hispanic or African-American backgrounds talk about how Carmen Sandiego and Lynne Thigpen’s character of The Chief were fixtures that helped them stay interested in education–early milestones in the game industry’s quest for diverse representation.

The seeds sown by the 90s educational games have continued to influence the game industry over the years, and their lessons remain relevant both for designers working in the entertainment space. With strong digital distribution models and an informed and nostalgic consumer base now having kids of their own, will we soon see a strong attempt to revive the genre?

And knowing how it all fell apart before, could it be kept from collapsing once again?(source:gamasutra)

下一篇:对独立开发者有帮助的工具包

闽公网安备35020302001549号

闽公网安备35020302001549号