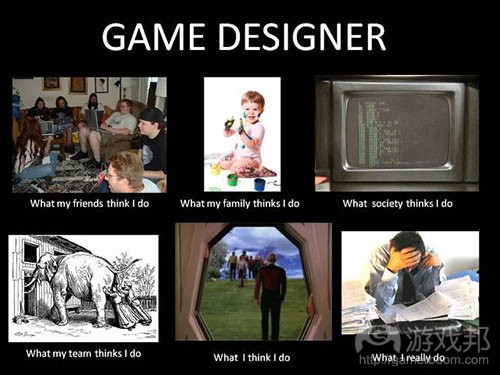

万字长文,从知名游戏设计师角度谈游戏设计概念,下篇

篇目1,Brice Morrison解构游戏设计的五个层面上篇

作者:Brice Morrison

分析游戏设计标准之核心体验

制作出一款非常成功的游戏只是因为运气?或者因为你使用了一些系统化的方法?是否那些能让我们感到开心并能够丰富生活的游戏只是开发者运气或正确决策的产物?是否有哪 种方法能够用来分析成功游戏的优劣?并将其真正落实到你自己的游戏中去。

我认为这些问题的答案是肯定的:即我们可以去策划,学习,并按照可靠的范例去设计并开发游戏。一些成功的公司,如任天堂,Valve,Zynga以及暴雪也会同意这个答案。一些 传奇游戏的设计者,如宫本茂,Will Wright以及Peter Molyneux也可能会赞成这个答案。这些公司或者开发者都找到了合适的方法而让他们能够一年接着一年推出大受欢迎的游戏 。因为如果你的第三款或第四款游戏都能够取得好成绩了,那么这种成功便不再是巧合或运气了。

通过分析过去几年的那些独立游戏和公司巨作,我发现了设计与学习游戏还是有一套标准的方法。即使是游戏产业发生了变化也不会破坏这个标准。新的公司,新的类型,新的控 制器都不会改变它。不论是独立游戏还是公司游戏,这些标准都是一样的。那是一套不可改变的系统准则,而很多开发者经常会无知地忽视它。

这个方法被称为游戏设计标准,通常由五个不同的部分所组成:核心体验,基础机制,奖惩系统,长期动机以及美学布局。游戏设计的目标是提供给开发者,包括独立开发者以及 游戏开发老手们一个有力的分析和规划工具,并帮助他们去分析游戏的优劣从而学习并完善其未来的游戏。

这篇文章只是对于游戏设计标准的初步介绍,为那些不了解这个概念的开发者做出解释。而首先我们要先关注其中最重要的一部分,即核心体验。

game-design-canvas(from thegameprodigy)

关于游戏设计标准的概述

游戏设计标准是个用于分析并规划游戏极其发展的工具。通过使用它去定义成功游戏和失败游戏,我们能够更容易地掌握影响游戏成功或失败的因素。一旦我们理解了这个概念, 那么开发者便能够使用它去找到适合自己游戏的设计方法了。

游戏设计标准可以用来分解那些包含不同游戏的系统,并判断它们的构成要素是什么。正如上述所说,游戏设计标准是由五大因素构成:

核心体验-玩家在玩游戏时有何体验?

基础机制-玩家到底在做些什么?

奖惩系统-玩家在游戏中的哪种行为应该得到鼓励或者批评?

长期激励-是什么激励玩家继续玩游戏?

美学布局-游戏设置是如何体现视觉和音效?

在今后的一些文章中我们将以一些使用了游戏设计标准的游戏为例子,进一步研究这五个构成因素。而现在,我们先来讨论这五个因素中最重要的:核心体验。

什么是核心体验

孔子曾经说过:“听而易忘,见而易记,做而易懂。”

核心体验是每一款游戏的核心内容。玩家能够在游戏过程中由内而发地感受到这种体验。核心体验之所以重要,是因为每一款游戏的目的都是向玩家传输体验。明确定义了核心体 验的游戏将能够提供给玩家更多乐趣,并因此赢得利润。

真实的核心体验可以由开发者自行决定时间。同时开发者也可以选择提供抽象的核心体验。

作为一名军人在战争中战斗(游戏邦注:《使命召唤》,例子在下文详述)

不断锻炼而成为一个健康的人(《Wii Fit》)

就像一次有趣的探险(《塞尔达传说》)

成为一名懂得社交的农场主(《FarmVille》)

以另外一个人的身份生活(《模拟人生》)

成为警员或者罪犯(《侠盗猎车手》)

生活中的每一个碎片都是一种体验。而游戏也正是在研究如何将生活中的典型片段(按照开发者的兴趣)融入到游戏中,并让玩家感受到这些体验。书籍,电影和其它媒体也在尝 试着这么做。它们将读者带进一个生动的爱情故事中,或者让观众能够体验场景中的奋斗场面。而游戏与之相比做得更好,因为它让玩家能够采取行动,并真正加入游戏中,成为 该体验的一部分。

如果一款游戏成功地向玩家传达了这种核心体验,那么它便能够预测到玩家对于游戏的评价。开发团队应该清楚自己理想中的核心体验,而如此他们在开发过程中所做出的任何决 策便都会体现该体验了。完全忠实于核心游戏体验的游戏开发能够造就一款优秀的艺术品。

核心体验的历史:从象棋到第一人称射击游戏

我们认为,一个好的核心体验必须是真正吸收了现实生活中的某些方面。当然了,一切皆有可能,在游戏产业中也因为一些趋势和偏好而构成了我们现在的游戏方向。让我们纵观 核心体验的发展历史从而更好地理解我们今天所看到的核心体验。

早前的游戏或者体育运动中总是在表达一些冲突的理念。在很久很久之前,当计算机时代刚刚来临之时,象棋和击剑便是传统游戏的最佳例子,并与早前的游戏有一些相似之处。 这些游戏的核心体验都围绕着战斗;如象棋模拟了策略战争,让玩家在游戏中做决策,并为了获得最后胜利而必须做出牺牲。而击剑游戏则为玩家再现了中古战场那种一对一搏斗 的场景。

同样的,与游戏一样的活动,如跳舞或音乐也有很长的一段历史。这类型的活动远离了冲突,充满了各种和谐感,注重参与者间的交流。小提琴手随着鼓手的节奏拉着琴,并反复 进行这种节拍。跳舞时,领舞的一方需要轻柔地拉着对方在舞厅里来回旋转滑行,而在整个过程中无需任何的言语交流。当对方也同步感受到相同的喜悦时,核心体验便成功了, 这就是一种让两个或者更多人体验到相同感受的概念。

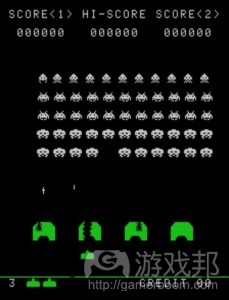

在70年代,当电脑辅助的视频游戏横空而降而投币的游戏机也渐渐开始走红之时,游戏开始趋向于关注挑战体验了。包括人与机器以及人与人之间的挑战。《Pong》以及《太空入 侵者》吸引了玩家长达一个季度的关注便证明了它的魅力。在游戏中,几乎所有玩家都能够登上高分排行榜中,并且都能够展示自己的技巧和才能。这时候游戏的核心体验来自于 玩家战胜了自己并战胜了游戏中的挑战,也就是战胜了之前玩家的游戏成绩。在这种投币游戏产业里,玩家的能力对于核心体验有很大的影响,而这类型的游戏直到90年代仍然大 受欢迎,即使它们的设计已经不再适应时代变化了。

在八九十年代,比起个人的高分表现,游戏开始以更广泛的标准去区分核心体验。在当时最受欢迎的角色扮演游戏,如《最终幻想》或者《塞尔达传奇》都更加侧重于故事描述, 而非玩家的自我表达。这些游戏都迫使玩家去听一些关于骑士或农民在过去的探险或者未来发展的一些悲惨故事。所以这个时期游戏的核心体验是侧重于模仿不同的故事。开发者 通过开发游戏角色,勾画游戏世界,添加游戏故事(美学布局)等去创造这种体验。通过扩展这种核心体验的可能性,开发者能让玩家在虚构的游戏世界中进行一些有意义的行动 ,并让他们能够尝试自己从未尝试过的东西。

从2000年以来,游戏有了进一步的发展,并开始呈现给玩家更广泛的游戏体验了。紧随着90年代的游戏传统,这个时候的游戏希望玩家能够感受到与现实世界不一样的游戏体验, 而且因为技术的进步使得这种体验也比早前的游戏更具有吸引力。在这个时代里,《侠盗猎车手》与《孢子》也比早前的系列更具有真实性了。包括水,烟,建筑,人群,人类和 非人类,音效等都比之前更加真实,但是核心体验却保持不变,即讲故事,进行冒险,完成任务,反败为胜。

其它现代游戏也力求将玩家的真实生活片段带进核心体验中。Wii Fit同时也帮助我们丰富了游戏以外的生活。玩家在游戏中不再仅仅为了获得高分而努力或者只是一味地想要沉浸 在虚构的游戏故事中,反而他们更能够从中去品味并改善自己的现实生活。

核心体验案例:《使命召唤:现代战争2》

使命召唤:现代战争2(from inquisitr.com)

《使命召唤》是一款成绩显赫的系列游戏。凭借广告宣传而最新发行的那个系列堪称是游戏产业中最大且最具侵略性的游戏,即单在游戏发行的第一天就获得了超过470万的销量。 取得如此好成绩便是因为这款游戏意识到核心体验的重要性,始终坚持落实核心体验,将其贯穿于游戏始终。

《现代战争2》有一个非常严格的核心体验:当前作为一名士兵。这是所有接触游戏的玩家都能够感受到的体验。与相同类型的其它游戏相比,这款游戏凭借销量和玩家的称赞,无 可厚非是位优胜者。游戏中的点点滴滴,包括喷射机翱翔云霄(美学),游戏的得分结构和武器(奖惩系统),多人模式中的排名系统和晋升体系(长期的激励)等所有方面都支 撑着游戏的核心体验。

针对于游戏中的每个功能,你都要自问:“如何做才能让玩家感受到这些功能?”答案都一样:必须让玩家感受到自己就是在战场上战斗的士兵。

游戏中的方方面面都应该重视这个问题,因此游戏才能得到玩家的喜爱。如果这些附加功能在游戏开发过程中就已经存在着,那么电子游戏开发商Infinity Ward的开发小组一定不 会让它们一直延续到成品游戏的身上。因为游戏的制作始终强调着一致性。

让玩家能够坐在起居室的沙发上手握游戏控制器便能够感受到与恐怖组织之间的战斗,那么这真的是一个伟大的创举。这种对于人脑的“欺骗”只能是那些特定且明确的核心体验 能够给予的,而且也必须得到游戏设计标准的其它四大因素的支持。《使命召唤:现代战争2》正是为玩家呈现出了力量与控制这种核心体验,所以才能取得如此巨大的市场份额。 如果一款游戏能够描写它的体验并根据游戏设计标准去分析这种体验,那么它的成功便不再是话下了。

核心体验对推广和销售的影响

核心体验是游戏设计标准的中心内容,因为它能够影响游戏中的每一个方面。游戏的基础机制,奖惩系统,长期激励以及美学都是围绕着核心体验而发展变化。如果游戏的核心体 验平淡无奇,那么其它因素亦然。因此,不仅是游戏开发团队对于游戏的核心体验充满兴趣,市场营销团队也同样对其充满好奇。

当你完成了一款游戏并打算将其投放市场供全球的玩家下载时,你应该回答玩家一个问题,即“游戏的核心体验是什么?”如果玩家听说一款游戏很“优秀”,那么他们也不会仅 仅依靠这种评价便去购买游戏。玩家需要知道自己能够从游戏中获得何种体验。是忍者探险还是阅读导师?不论你提供的是何种游戏体验,这都将成为游戏销售的市场营销口号。 玩家关于游戏的每一个评价都与游戏体验有着直接的联系。

游戏设计应优先确定核心体验

最后,游戏的成功与失败都是基于它们对于核心体验的选择,而核心体验执行的成败更是归结于对游戏设计标准其它因素的贯彻。基础机制,奖惩系统,长期激励以及美学布局都 深深扎根于游戏中,并随着核心体验的发展而发展。这就是为何定义核心体验对于开发团队来说是如此重要了。而且这也是游戏开发中的首要任务,如果你发现自己的首次尝试是 错误的,那你就需要去调整它并因此改变其它因素。如果没有了核心体验,而只是把游戏设计标准的其它四个因素之一当成最重要因素,即使创造出震撼人心的视觉效果或者扣人 心弦的游戏故事,但是最后的一切也不会有多大意义。

如果你的游戏并不能让玩家感受到核心体验,那么再棒的游戏内也不可能让其取得成功。即使玩家会在评论中赞扬你的图像,音乐或者音效(美学),但是整体的游戏乐趣也只 能是平淡无奇了。

然而,如果你能很好地定义游戏的核心体验,并竭尽全力为玩家创造这种体验,而且这也是玩家心目中的理想体验,那么游戏的成功便是指日可待了。

分析游戏设计标准之基础机制

Dave目前正在着手自己的大型独立游戏。他已把握题材和总体构思。这是款有关僵尸的动作/冒险游戏,玩家吸收受害者的血液。玩家得避免日光曝晒,游戏涉及浪漫爱情故事。听 起来是款不错的游戏。

他向业内好友陈述自己的想法。他的激动之情溢于言表,他非常喜欢僵尸吸血这个游戏。但当好友问及:

“玩家如何盗取血液?”

Dave告知好友僵尸可以瞄准任何人,吸取他们的血液,这就是游戏的运作方式。但好友反复表示,“玩家点击什么按键?你如何通过按键点击传递僵尸盗取他人血液的信息?”

Dave低头不语,发现自己的构思虽然理论上看颇为有趣,但有些操之过急。

巧妇难为无米之炊

Dave的构思也许非常不错,但能否最终实现?这要看情况;构思都很好,但其中缺乏组织关系。Dave没有腾出时间创建游戏基础;他只是从某些有趣故事下手。若Dave草率动手, 未先创建联系,就开始根据构思编码,游戏最终很可能只是款同其他作品大同小异的普通之作。也就是说游戏难成为轰动巨作。

要想构建僵尸体验,Dave需在制作初期思考基础机制。

就如之前提到的是,本系列的“游戏设计标准”是个分析和规划方式,游戏开发者可以凭此设定游戏轮廓、目标和用户体验。通过运用这些标准,设计师能够围绕预期核心体验创 建游戏内容。

通过这一系列的游戏设计标准,设计师、开发商和用户能够描述和分析游戏的核心要素。此前我们就已谈及核心体验的重要性,就是开发者希望用户体验游戏时收获的感觉。本文 主要谈论基础机制。

不妨先来看看一个类比例子。房子由砖块砌成。大家走进房子的时候不会想到砖块、木头和管道。新屋主不会像好友吹嘘房子使用什么泥浆;他们期望瞄准其他更优的元素!他们 希望展示时髦木质地板、大理石案台,或者多层供暖设备。砖块是基础元素,若砖块的堆砌方式不当,那么其他都免谈。

同样,游戏也是由基础机制构成。这些机制是玩家的实际操作活动。当玩家点击按键时,屏幕就会出现反应。当玩家移动鼠标时,游戏就会出现变化。当玩家移动Wii遥控或其他输 入装置时,目标就会出现变化。这些互动是组成游戏的要素,非常重要。矛盾的是,玩家通常不会过多考虑游戏机制。要想呈现高质量作品,开发商就必须专注于这些“砖块”。

基础机制

基础机制是一组玩家操作&反应活动。虽然玩家考虑的也许是游戏故事、关卡目标,或其他设计标准中的高级元素,但他们每时每刻进行的内容都能够通过基础机制陈述。丧失基础 机制,玩家就没有可操作的内容。

游戏需要玩家同内容进行互动。若玩家未同内容进行互动,他们就不是在体验游戏,他们只是观察内容,并没有参与其中。玩家的互动内容很多(游戏邦注:就现代游戏而言,主 要是按键的点击;就运动控制游戏而言,主要是遥控手势)。除电子游戏外,还有运动游戏的活动操作,棋盘游戏的移动操作。这些是玩家采取行动影响游戏内容的体现。

游戏具有象征性。游戏赋予某些活动特殊意义。若我拾起木制小人,在桌面移动,这个活动没有意义。但若是在国际象棋游戏背景下,这个操作的意义是我通过小兵进攻对手。

基础机制具有各种类型。要想正确运用至游戏,我们需要把握这些类型的具体内容。

原子基础机制

有些基础机制呈原子形式,也就是说它们是游戏中最小的动作&效果组合。这通常是单个按键点击或手势,这也可能更复杂些,取决于游戏。重点是,在游戏游戏规则中,这些动作 无法分解成更小内容。

Atomic Base Mechanic from thegameprodigy.com

在《宝石迷阵》中,玩家需点击不同宝石,交换它们的位置,将3个同类宝石排成一列。这里的原子基础机制是玩家点击单个宝石。玩家点击产生的反应是宝石移动。虽然这款游戏 已被各类玩家玩过数亿小时,所有玩家活动都是点击宝石,然后移动。整个过程反反复复。

《Wii Sports Tennis》的原子机制是玩家摇摆Wii遥控,令角色挥动球拍。玩家通过此行为体验各场比赛。

许多游戏都由极少原子基础机制构成。上述两个例子只有一个原子机制。即便是复杂现代游戏最多也只有3-4个原子基础机制。战斗游戏包含攻击、防卫和移动。第一人称射击游戏 通常包含进攻、防卫,运用魔法和道具。这些游戏也许会粉饰这些元素,将其变成复杂链条,但玩家进行的原子操作通常非常简单。

原子基础机制非常有趣,因为他们以略显无趣的科学方式呈现游戏。虽然制作游戏的目标是获得核心体验(游戏邦注:体现在玩家感受),但实际组成“砖块”通常没有整体内容 那般有趣。思考下列游戏的趣味性:

* 你所要进行的操作是移动球体,试图将其射入特定区域

* 点击某物,然后选择期望互动方式。这就是游戏。

* 所进行的内容是阅读文本,基于不同选择进行抉择。

不是很有趣,是吧?但它们是某些倍受欢迎游戏的原子机制。

* 足球运动

* 《模拟人生》

* 《最终幻想》,或经典RPG游戏

这些例子说明我们不能够通过原子基础机制描述评判游戏。这就好比阅读许多关于某人的事迹后称自己了解此人。“此人有棕色头发,身材颇高,喜欢烘培。你喜欢他吗?”这是 电脑的思维方式,但人类会更深入地思考。只有待到我们深入下层基础机制,游戏的核心体验才会开始显现出来。

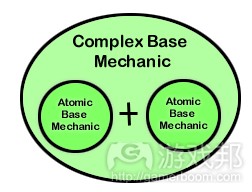

复杂基础机制

原子基础机制非常重要,但游戏的内容当然远不止奔跑和跳跃活动。玩家奔跑于拥挤城市,努力向上跳跃,同时确保头部不触及建筑顶部。他们奔跑越过缝隙,然后跃至3个敌人之 上。他们持续奔跑,然后停下等待守卫穿过,然后继续奔跑。

Complex Base Mechanic from thegameprodigy.com

复杂基础机制形成于各种原子机制绑定起来创造新内容。玩家通常只有在掌握潜在原子机制后才能把握这些新行为。游戏会告知他们,或给予充足时间,让他们自己发现。

在《宝石迷阵》中,我们曾谈到游戏的原子基础机制是玩家点击两个宝石,交换它们的位置。这令玩家得以串联3个宝石。但若玩家连接的宝石超过3个?通过点击宝石将其放置于 合适位置!若它们形成链条,玩家将获得额外较高积分!通过以特定方式执行原子基础机制,玩家能够完成创建链条的复杂基础机制。

在国际象棋中,开旗法是指玩家故意牺牲某棋子换得长远优势。例如,他们可以将小兵放于易受攻击的位置,因为当对手拿下小兵后,他们将处在更加危险的位置。象棋的原子机 制并未涉及此概念。这属于复杂机制概念,结合若干原子机制创造更加有趣的内容。

开发商如何支撑复杂机制完全取决于他们自己。例如,在复杂游戏中,玩家能够奔跑和跳跃,所以当然他们也能够通过同时奔跑和跳跃到达新 高度。开发商可以让玩家通过既有原 子机制完成此操作,或者他们可以选择添加额外内容,从而使跳跃+奔跑组合操作能够让玩家跳得更高,并伴有新的特效和音效(游戏邦注:开发商如何创造此内容及其他复杂基础 机制完全取决于他们自己)。

全局视角

基础机制是游戏的构建模块,但它们主要依赖于游戏设计标准中的其他元素。虽然它们组成玩家所操作的活动,占据玩家所有体验时间,但仅由基础机制构成的游戏相当乏味。

游戏奖惩系统赋予玩家行为含义;玩家如何知晓操作什么内容及何时进行?这些机制应通过什么方式进行运用和优化?长期奖励促使玩家继续饶有兴致地反复操作这些基础机制。 美学布局给予玩家行为此刺激因素:当玩家以正确顺序完成操作时给予玩家漂亮的“结合物!”所有这些要素都同基础机制及玩家行为联系密切,赋予操作相应意义,促进传递核 心体验。

“千里之行始于足下”

就像古话说的,“千里之行始于足下”。同样,游戏也是一步一步构建而成,由各个基础机制组成。持续支持核心体验和基础机制能够给各游戏创造构建模块,引导玩家的各体验 时刻。若这些“砖块”组建合理,将创造惊人体验时刻。

篇目2,Brice Morrison解构游戏设计的五个层面下篇

分析游戏设计标准之美学布局

是否有人会关注角色是穿着银色护甲还是橙色的披风?军队在欧洲和亚洲战斗有何差别?拯救世界和拯救自己真正喜欢的人和游戏之间是否有区别?

事实上,这些元素确实会对游戏产生影响,而且影响还很大。画面、音效和感觉构成了游戏的核心体验,这是游戏其他部分所无法比拟的。正是它们使得游戏成为了一种真正的艺 术形式而不是单纯的科学产物,正是它们让游戏显得更接近戏剧而不是算数,恰似绘画艺术而不是几何绘图。这些艺术内涵就像是游戏的皮肤、脸和外在表象,是世界在审视游戏 时看到的内容。

以下是游戏设计标准之美学布局的相关内容。

美学布局的组成要素

硬核玩家甚至某些游戏开发者时常会将游戏当成纯粹的机制化系统。这可以理解,因为上述人群通常都玩过大量的游戏,他们已经成为了这个领域的专家。他们可以分析和解剖游 戏,透过游戏的表象将其花里胡哨的外观分解成最基本的齿轮和机油。我们游戏设计标准中探讨的所有系统,包括基础机制、奖惩系统和长期动机,都属于此类齿轮。一旦他们能 够将这些内容分析清楚,那么就可以尽其所能操作这些齿轮,得到他们想要的东西。

这个过程被游戏开发者称为“最小最大化”。最小最大化过程就是利用最小的经历让游戏获得最大化的好处。玩家和游戏开发者是这个方面的专家,他们可以迅速地理解整个游戏 ,然后寻找并执行可选的路径来达成目标。这种老式的思维模式可以追溯到当年的街机游戏,当时游戏的核心体验便是征服挑战并获得最高分。使用最小最大化策略并没有过错, 将游戏设计当作系统来看待可以创造出有趣的最小最大化情形。

但是,游戏所具有的不仅仅是机制和系统。美学布局便能够赋予游戏技巧、格调和典雅,决定角色的模样、跳跃或奔跑时的音效以及油画或刚强超现实主义的背景,过场动画和系 列电影,故事和情节主线,游戏盒子的外包装。执行恰当的美学设计能够让优秀的游戏受到关注并且被用户所铭记。设计不佳的美学甚至会毁掉整个游戏的体验。

游戏的美学布局由许多关键的子部分组成。前3大子部分可以在几乎所有的传统电子游戏中看到,那就是视觉效果设计、音效设计和内容。第4个子部分也存在于所有的游戏中,但 是多数传统主机的PC游戏并没有过多地考虑这个方面,那就是互动设计。

视觉效果设计

游戏的视觉效果设计很容易理解,但是却很难掌握。视觉效果就是游戏的外观,包括图像、颜色、屏幕上或者玩家手中卡片上的图画。由于人类对视觉的依赖性最强,所以游戏的 视觉效果至关重要。这是将出现在海报、广告和零售盒包装上的最为主要的游戏层面。船长的脸部和随风飞舞的头发的细节、水面上的闪光或者耀眼的太阳光,这些都属于游戏视 觉效果设计的一部分。额外添加某些内容完全不会影响到游戏可玩性,却能够以重要但间接的方法丰富玩家的游戏体验,比如《使命召唤》中从头顶上飞过的飞机。

现在,游戏在这个层面上比过去要好得多,这需要归功于过去三十年来技术上的进步和那些富有开拓精神的艺术总监。在上世纪90年代,当时流行的是Super Nintendo和初代 Playstation,开发者们追寻的是在游戏中呈现完美的现实主义,他们的目标是制作出完全吻合现实生活的游戏。这十年来,上述目标已经几乎在Xbox 360和Playstation 3上实现 ,开发者们便开始自寻其路,形成自己的风格。

《Farmville》之类在线网页游戏精通的是高清卡通画图像,让玩家觉得舒适而且易于理解。《Spelunky》等独立游戏追求的是90年代像素艺术的改良版本,勾起那些童年体验过任 天堂游戏的成年人的回忆。《Okami》或《塞尔达传说:风之杖》等游戏专注的是提供高程式化的效果,让玩家产生诧异感。所有的这些视觉效果设计都支持了相应游戏的核心体验 ,为其他开发者提供了可以模仿或者超越的高质量范例。

游戏的视觉效果设计能够传达出大量信息,比如哪些人会玩游戏以及这些玩家对游戏的期望。网页游戏容易理解并且有着简单的规则,但是它们或许无法让那些追寻《战争机器》 等超现实主义感的玩家产生兴趣。因而,将这类游戏的艺术风格现实化完全是在浪费精力,在决定视觉效果设计风格时,明白游戏将吸引哪类玩家非常重要。对许多玩家而言,这 个子部分的质量非常重要,尤其是第一印象。即便游戏的剩余部分很不错,但是如果视觉效果的质量越过了玩家所能够接受的底线,他们也很难会想去尝试游戏。视觉效果设计是 能最快让游戏显得过时的因素。

音效设计

游戏的音效和音乐很重要。观察过电影行业之后,游戏行业迅速明白,音乐能够被用来引发玩家在游戏中的情感和沉浸。勇敢的英雄骑马奔向敌人时,配乐应当是管弦乐和小号。 更富娱乐性的游戏或许会使用充满童稚的音乐,比如游戏《Wii Play: Tanks》,让玩家回到他们的童年。诸如《生化危机》之类的游戏选择使用动态音轨,改变音乐依赖于屏幕上 的动作的情况。在玩家在黑暗幽静的街道上游曳时,听到的是令人紧张的低沉音乐。而当怪物从墙边冒出时,音乐就会变得急促快速。通过美学布局的音效设计,所有的这些选项 都为核心体验提供了支持。

wii play_tanks(from forums.toucharcade.com)

除了背景音乐之外,游戏的音效也起到重要的作用。仍以《Wii Play: Tanks》为例,任天堂本来可以将小坦克的音效设计成第一人称射击游戏中那种庞然大物的音效。但是他们却 选择将它们的音效制成类似于那种上发条的玩具。这个看似并不重要的改变针对的恰恰是游戏的目标受众,这种设计会让那些想要驾驶真正坦克的玩家离开游戏,而加深了那些想 要再次体验塑料车辆的玩家的体验。

需要花较长时间来玩的游戏可能不需要背景音乐,但是含有故事情节的游戏时常会使用背景音乐和音效来提升游戏效果。而且,视觉效果和音效设计能够相辅相成,用来表现某个 事件的发生,比如当玩家受到伤害时屏幕会变成红色同时会听到砰砰的心跳声。这些都是开发者和音效设计师需要考虑的做法。

内容

游戏的内容包括角色、故事、场景和关卡设计。从开发层面上来说,内容通常被视为由设计师和制作者(游戏邦注:而不是工程师)负责的游戏部分。无论是推翻邪恶的Ganondorf 还是寻找已经遗失很久的珍宝,游戏的故事主线确属于美学布局中内容的一部分。就像美学布局的其他层面一样,内容有时并不会对游戏的机制化系统构成任何影响,只是帮助寻 找出那些真正对游戏感兴趣的人。以中世纪为背景的角色扮演游戏或许并不会满足那些选择以现代高中为背景的同类游戏的玩家的诉求。

开发者能够以自己喜好的方式将游戏的故事和角色成分插入游戏中。游戏是构建在规则和玩家的行动(游戏邦注:这些是游戏的基础机制和P&R系统)之上,但是玩家的游戏体验就 与游戏内容相关。每个关卡提供新内容,这是玩家之前并未见过的场景。游戏故事、角色和情节的重要性完全取决于开发者。有些玩家偏向于最小最大化,他们会跳过所有的故事 情节。或者,开发者可以像《Braid》那样把故事情节分离成可选项。内容对玩家的重要性由开发团队来决定。

互动设计

美学布局的最后一个子部分是互动设计,也就是玩家同游戏互动的方法和技术。无论是通过按键、移动、模拟操纵杆、网球拍还是其他已经被发明出来的设备,玩家与游戏进行互 动的方式不仅是美学布局中最重要的层面,也是整个游戏设计标准中最重要的层面。

多数视频游戏使用手持控制器来玩,但是我们这里所定义的标准适用于所有游戏,而不仅仅是视频游戏。玩家用来同游戏进行互动的器具和设备属于游戏美学布局的一部分。这些 设备能够发挥何种作用取决于基础机制,玩家所做的动作的结果取决于奖惩系统,但是设备本身也能够起到决定性的作用。

正如我们已经说过的那样,有着两个操纵杆、一个方向盘和数个按键的传统游戏控制器只是游戏互动设计的形式之一。任天堂的Wii遥控器便是个不同的互动方式,玩家需要的只是 将遥控器对准电视即可。与传统视频游戏互动设计相差更远的是足球类的运动游戏,玩家踢的是真的球,而且在场地上进行互动。另一个范例是《Poker》,玩家在游戏中交换和接 收卡片,使用特别的手势来回应叫牌或者盖牌等动作。在这些情形中,互动设计都会影响到玩家与游戏及其他玩家的互动体验。

这些设备和系统给予游戏非同寻常的美学感受。游戏开发者需要决定游戏将采用何种互动设,了解这样的选择会如何提升或损害游戏的核心体验。仅仅使用控制设备是远远不够 的,因为这种趣味性显得并不充实,比如,玩家每次开门时都需要使用Wii遥控器。开发者需要思考和揣摩的是,自己所做出的美学选择会对玩家的体验产生何种影响。

美学布局对玩家的重要性

game design canvas(from thegameprodigy)

就吸引玩家尝试游戏这个层面而言,美学布局是我们所谈论的游戏设计标准中最为重要的成分。在游戏开发方面(游戏邦注:尤其是设计和编程方面)有丰富经验的人往往会忽视 游戏中图像和音效的重要性。但是,忽视美学布局的重要性,往往是自食其果。比如,许多独立开发者倾尽心血创造有着复杂和创造性基本机制的游戏。但是,他们并没有考虑、 调查甚至想到过游戏的图像、音乐和音效。正因为开发者的这种做法,最终会导致某些本来可能觉得游戏富有吸引力的玩家无法接受游戏。

你可以看到音乐唱片行业也有着类似的情况。在美国,乡村音乐在南部之外的州郡并不流行。许多人声称,他们听过所有种类的音乐,除了乡村音乐。尽管出现这种情况的原因多 种多样,但是这种市场的分裂性是显而易见的。如果听众听到他认为是乡村音乐的歌曲,就会自动把设备关掉。但是如果是他们更为熟悉的音乐,他们就乐于接受。

录音艺术师理解这种情况。将歌曲打上“乡村音乐”的标签会对歌曲的市场潜力产生影响。因而,成功的艺术师会在创作歌曲时对选项极为关注。他们会预先决定歌曲将进驻哪个 市场,然后挑选合适的创作方法。

结果,你时常会看到,流行音乐的主流和乡村版本之间的几乎没有差别。有时只是将背景器乐从班卓琴(游戏邦注:乡村乐器)变为电吉他(游戏邦注:主流乐器)。这边是两个 版本的歌曲间唯一的差别之处,但是这种微小的改变便能够产生很大的影响力。有些人听到班卓琴的版本之后,在数秒之内便会认为他们不会从这首歌曲中获得乐趣。他们会完全 抛弃这首音乐。但是,同首歌曲的电吉他版本就会被当成其他流行歌曲来对待,这些人可能会认为自己也能像其他流行歌曲那样喜欢上这首歌曲。

回到游戏行业中,开发者关注美学布局对游戏认知产生的影响必然会使游戏受益。如果可玩性独特的游戏因为美学布局的不佳而不受玩家待见,这完全是个悲剧。比如,某个游戏 的目标用户是老年妇女,但是却使用上世纪90年代的中古场景的RPG游戏图像。

结语

美学布局对开发者来说至关重要,因为它能够决定游戏的用户。图像、音效、故事和输入设备虽然看似与游戏设计的其余部分并不相干,却能够显著地决定某个玩家是否将接受游 戏。而且,这也是艺术师在游戏上打上自己烙印的机会,可以将这种简单的电脑游戏转变成艺术巨作。通过这些元素的使用,游戏开发者可以开始构建和完成他们的艺术作品,供 全世界玩家进行互动。

分析游戏设计标准之长期动机

是什么支撑着玩家对一款游戏不离不弃?是什么让30秒的游戏经历拉长至30小时?

回答以上问题以前,我们先思考:玩家一开始玩游戏的动机是什么?显然,为了娱乐和享受。感受追击、挑战和寻找的紧张感,与他人的交流互动,提高自己的操作技能或在在游 戏世界里探索冒险——这些都是核心体验,这也正是玩家最初开始玩游戏的原因。玩家希望得到有趣的体验,而游戏正好充当了玩家与体验之间媒介。

玩家开始游戏了,然后呢?每一款游戏都是一个新国度,玩家就是新国度的探索者,他们进入游戏寻找核心体验。在一路的跳跳跑跑中,玩家的游戏人生开始了。在游戏所创造的 社会结构里,玩家与游戏互动。寻找体验的过程首先从了解并适应游戏的基本机制开始,也就是,学会在游戏世界里活动和生存。

玩家学会游戏的基本机制后,就可以学习更加宽泛的游戏玩法了。一开始玩家只会跳,但现在他知道跳以前得先看好位置;一开始玩家开门见山就谈敏感话题,现在他知道讨论时 还要尊重对方;一开始玩家只知道见了敌人就开打,现在他知道对付红色的敌人得用红色的炮弹才有效。总之,他开始把自己的行为和游戏给予的结果联系起来,这样,他渐渐地 明白了游戏世界还存在一个指导着”新国度的居民们”有所为有所不为的奖惩系统。这套高高地建立在基本机制之上的系统,指引着新国度的探索者们深入到核心体验之中。

再然后呢?

玩家们已经周游了这个国度(游戏本身)、理解了这个国度的体制、体验了这个国度的生活,还有什么值得他们留恋的呢?还有什么能让玩家不断地采取相同的举动、实施相同的 策略、参与相同的活动,周而复始,不厌其烦,甚至仍然乐在其中?

为了目标而努力

在设计良好的游戏里,玩家坚持玩某款游戏是因为玩家有所追求,他们是为了某个目标而坚持不懈。所谓的目标未必如你所想的那样明确,甚至对玩家来说也不是非常重要。事实 上,玩家可能没有意识到有一个目标在牵着他们的鼻子走。但确实有一个目标存在,即动机,让玩家坚持玩某款游戏。

在《超级马里奥兄弟》里,玩家只要不断地玩下去,就可以不断地通关不断地进入新地图。在典型的投币游戏,如《吃豆人》,玩家的长期动机就是拿到最高的积分。在《孢子》 或《尼特》这类探索游戏里,玩家的目标只是不断地发现新东西、探索未知。以上这些都是在玩家已经“吃透”游戏后还能坚持玩下去的诱因所在。与游戏的其他成分一样,长期 动机也可以扩宽游戏玩法。

没有长期动机的游戏算不上一款完整的游戏。以上体验类型更像是玩具。玩家先了解他们能做的行为(基本机制),再研究行为与结果之间的关系(奖惩系统),接着欣赏游戏的 内容(美学布局),然后……没了——能研究的都研究了,能玩的都玩了。

玩具Vs.游戏

我们来看一个简单的例子:假如你走在大街上,看到一个蓝色的小皮球。“有意思!”你这么想着,“按一下会怎么样呢?”你按了一下皮球,它马上像被施了魔法一样蹦起来。 “哇!有趣!”你这么想着又按了一下,不过这回好像没有跳得那么远了。“看来要让球一直跳,我得有节奏地按。”你验证了自己的猜想,假设成功。但是玩了不一会了你就厌 倦了,不玩了。

这就是长期动机缺失的例子。但是,把这个按球活动中增中一个动机,就可以创造一个游戏了。想像一下,你看到球后,又在街的另一边看到一个盒子。“我要把这个球投到那个 盒子里!”此时,你就有了一个动机——把球投进盒子里,你就赢了。

虽然这个例子很简短,但请注意是什么拓展了蓝球的玩法。当你把球投进对面的盒子里时,没有新的机制产生,也没有新的奖惩系统起作用。只是有一个目标激励着你去展开行动 、指引着你去解决困惑。

普遍的长期动机

游戏中存在着许多长期动机,以下列举了一些比较普遍的类型:

1、通关。这种类型的长期动机流行于早期的电脑游戏,且仍然在当下许多主流硬核游戏中长盛不衰。例如,战士必须穿过枪林弹雨,或者英勇的怪物猎人必须拯救王国,才能开启 游戏的下一章节。玩家完成一个阶段就进入下一个阶段,整个游戏如此生生不息。通关的另一个变种是积分:玩家已经累积了115876点积分,只要再多射死一个太空入侵者就可以 多拿一点积分,怎么能在这个关头就不玩了呢?

太空入侵者(from thegameprodigy)

这种长期动机的升级版是给予玩家代表不同等级的奖牌金银铜,或代表不同积分层次的ABC,其本质就是“通关+积分”——玩家不仅要通过某道关卡,还要在这道关卡中争取得到 最高分。这个版本非常接近我们将要提到的下一个流行的长期动机……

2、收集物品。有些玩家几近偏执,他们非得把每一块石头都翻开,每一个宝箱都打开才肯罢手。只要还有东西可以收集、还有事情可以做、还有任务可以完成,他们就绝不会离开 ,直到一切都处理得妥妥贴贴为止。这动机的变种包括角色满级、找到所有特殊物品或收集所有成就。

有些游戏对收集目标设置得很清楚,比如对每个成就都贴上标签。RPG给玩家开辟了许多副本,供玩家收集更高级的装备等。虽然副本并不需要玩家完成游戏(游戏邦注:除非是对 成就解锁的拙劣模仿),但确实大大延长了玩家的游戏寿命。

3、获取新信息。许多游戏设置了悬念信息来吸引玩家继续玩下去。剧情就是其中一种。即使策略/战略游戏的关卡变得相当无聊,玩家仍然会继续玩下去,只要他们还关心Leon王 子或自己喜欢的其他角色又发生了什么事。在《Flow》中玩家可以看到一个洞穴的深处或海洋底部,但尚不清楚会发生什么事。当那些形态各异的海怪若隐若现,玩家禁不住好奇 潜入更深的水域,一窥究竟。

4、升级技能。《街霸》、《光晕》等动作游戏长久地占据玩家的“芳心”归功于升级技能。技能升级意味着攻克困境,或战胜强敌。为什么玩家能够一次又一次地沉浸于相同的战 斗、相同的关卡、相同的武器和动作?这就是长期动机在起作用。长级技能有时候与等级系统相结合。如《光晕》,根据玩家的技能等级,安排遇上有相似技能的敌人。这就更进 一步刺激玩家磨炼技术以战胜敌人。

单一或多重?明示或隐藏?

长期动机不一定要按时间来分。任何有意义的方式,只要能鼓励玩家继续游戏的都是长期动机。要在游戏中放入什么样的长期动机取决于游戏开发者。有些游戏看似不完整,正是 因为缺乏真正的长期动机;有些游戏只有单一的长期动机;现代游戏大多有数个长期动机,可以说在深度上已经升级到专业水准。一款游戏有许多让玩家追随的东西,如果其中一 种玩腻了,玩家还能继续追求另一种。如此一来,开发者就好像为游戏上了双重保险,有效地防止玩家从游戏中流失。

除了决定单一或多重动机,开发者还可以设计动机的明确程度。有些游戏赤裸裸地把长期动机摆出来,如列出各个阶段的成就或者给予玩家非常正式的得分,有些游戏则隐晦得多 ,玩家玩这两类游戏时的感受是非常不同的。像《Spore》或 《Flow 》这类目标(游戏邦注:通关+获取信息)相似的游戏,却很少向玩家透露长期动机,而是让玩家自己去寻找 目标,从而产生一种他们是沿着自己的道路玩游戏的感觉。隐藏长期动机的好处是,让游戏本身看起来更接近核心体验;风险是,不明所以的玩家或者希望目标稍微明确的玩家可 能会感到厌倦。

拓展游戏玩法:多给胡萝卜还是多给大棒?

如何拓展玩法、延长时间?最简单的方法就是给玩家长期动机。然而,开发者得注意了:完全依懒动机来拓展玩法可能会给游戏带来灾难性的后果。因此,开发者应该意识到长期 动机对玩家的重要影响。

在此我给出一个直观的类比:胡萝卜和大棒。马想吃胡萝卜——奖励/长期动机。但胡萝卜悬挂在大棒上,想吃就得越过大棒的长度——任务或基本机制玩法。完成任务方得奖励。 创造一种和谐的游戏玩法是一门保持胡萝卜和大棒效力的技术。

如果基本机制和奖惩系统就是游戏的固定焦点所在,那么要让玩家保持对游戏的热情,难度不大。强制玩家去思考、专注技能和长期游戏是设计师的目标。难点在于如何长久地保 持游戏的新鲜度。如果你的游戏是以飞行为主题,那么我们可以很容易地想象到,玩家开着飞机从美国飞到加拿大。第一次学习飞行那是相当的有趣,第一次完成飞行任务那是相 当的有成就感。

但是,这种体验不会长久。如果游戏需要飞得更远,如从加拿大飞到中国,那会怎么样呢?这就相当于给游戏增加了更多根“大棒”,但大棒的长度还是一样的。当你增加了更多 根大棒,你就必须同时保证通过大棒的过程更有趣,或者让胡萝卜更加诱人。

例如,开发者可以说:“不错,你已经飞抵加拿大了。现在飞往中国吧。如果你到了,就奖励你一艘登月宇宙飞船。”在这种情况下,玩家可能会抱怨,因为眼前的挑战太耗时太 费神了,而且必须重复已经做过的事,然后就此退出游戏。但另一部分玩家可能会为了宇宙飞船而决定继续砸时间。他们太想得到那根胡萝卜了,所以宁可接受更多的大棒。这是 长期动机在驱使着他们。

避免“刷任务”行为

许多MMORPG,如《魔兽》,严重依赖长期动机来保持玩家的游戏热情。这通常导致玩家为了实现某个长期目标而不得不一次又一次地刷那些折磨脑细胞的任务。为了挣到足够的金 子去买装备,玩家刷了150只半兽人,这就是一个完全依赖长期动机的典型例子。如果不是长期动机的支撑,玩家可能早就离开这款游戏了。

一开始,玩家觉得好玩,但完全掌握了操作后,唯一让玩家坚持下去的就是追求最终目标。这就是有意思的地方,尽管玩家内心觉得十分无趣,但他们仍然紧咬着游戏不放。长期 动机的强大威力,有效地弥补了游戏玩法的日渐衰竭。

结语

保持游戏玩法和长期动机之间的平衡,是长久地保持玩家热情的关键。你不希望玩家离开游戏,但你同时也不想让他们玩你的游戏无聊到哭。最理想的情况是,开发者能将乐趣与 长期动机相融合,创造出一个真正迷人的游戏世界,给予玩家流连忘返的体验。

解析游戏设计策略之奖惩系统

我们的日常生活充满了选择。睡眼朦胧中听到闹钟作响,鲤鱼打挺跳起来还是摁掉闹钟继续睡?今天的晚饭是吃鸡、啃牛排还是吃素好呢?埋头工作还是和朋友外出玩?这些选择 就像一盒颜料,你用不同的色彩描绘每天的生活、工作仍至生命。正是通过这些选择,你体验自己的存在、向世界表达自己的存在。

如果人生是一场游戏,那么做这些选择的活动就是人生的基础机制,你有选择、有能力做或不做。这些行为就像生活的变量,你可以把它们输入生活这个系统。总之,无论是什么 行动,只要在你的能力范围以内,你就可以随心所欲地做选择。

真的可以这样吗?当然不可以。现实可没有你想象的那么自由。确实,你有选择权,但有选择就有相应的后果、要求和规矩。在人生这场游戏里,你也许有能力冲进图书馆大声喧 哗。你可能有能力侮辱最好的朋友或打劫便利店。你大约有能力沮丧地宅在公寓,不与朋友欢度周末。

以上都是你的选择,但你可能不会这么做。即使你有能力有办法去实施,还是受到其他指导性条件的约束。所谓“选择”的内涵远比你想象的要深刻。你的决定仿佛受到一股超脱 于自身的无形力量的主宰。

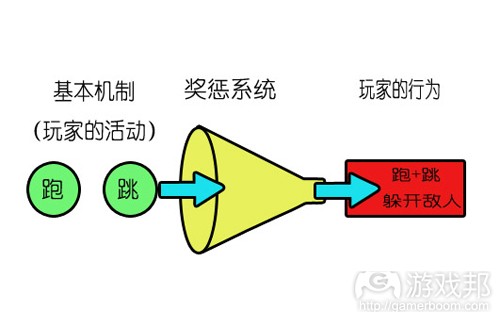

奖惩系统影响玩家的行为

正如上面所讨论的那样,游戏为玩家提供了各种选择。玩家可以跑、射、画、投、吃、躲、攻、瞬间移动等等等。但这些行为都不是孤立存在的,总是有一个更高级的系统——奖 惩系统统领这些行为,促使玩家从中做选择。奖惩系统同时赋予了基础机制以意义和份量,迫使玩家慎重考虑自己的选择。

因此,理解游戏设计中的奖惩系统是明白人类行为的重要课题。在特定的时刻,人的选择范围是很广的,然而,最普遍的行为只占了其中很小的比例。原因就是我们上面提到的, 有什么样的选择就有什么样的结果。无论是在现实生活还是游戏世界,人们都是从过去的经验中学习,然后根据预期的最理想的结果来选择当前行为。行为与结果的对应关系组成 了主宰玩家行为的奖惩系统。

在搞清楚奖惩系统是怎么一回事以前,我们先举一个简单的例子。在《超级马里奥64》中,游戏的基本机制就是跑跑跳跳着通过各个台面(暂不考虑战斗和能量源)。怎么使用这 些能力一边前进一边收集通关所需的星星取决于玩家本人。

super mario(from thegameprodigy)

然而,玩家控制马里奥的行为要受到游戏奖惩系统的约束。如果马里奥撞到敌人,那么他就会挂掉一条命。这是一种简单的惩罚,从中我们可以看出这个系统是如何影响玩家的行 为,这种影响远比我们所想象的要深刻。一旦玩家明白撞上蘑菇头就会损失一条命,那么他们的行为就会改变,不会像当初那么横冲直撞了。这就是惩罚的意义所在。

接下来,马里奥继续跑着,又遇到蘑菇头了。从技术上来说,玩家的行为中确实还存在一头撞向蘑菇头的选项,但游戏的奖惩系统已经告诉玩家此时应该躲避。因此,玩家会选择 操纵马里奥躲开蘑菇头。

现在你看出什么来没?游戏的基本机制没变,仍旧是马里奥的跑跑跳跳,但玩家的行为改变了。玩家对游戏系统“心领神会”后,他们的决定随之改变。

随着玩家与游戏及其奖惩系统的互动进一步加强,玩家开始形成心智模型——系统的运作原理和行动的最佳方案。玩家能否完全理解系统取决于玩家自身,而奖惩系统的工作就是 激发玩家的理想行为。一个好的游戏设计能够反映出玩家的理想行为,然后围绕理想行为构建奖惩系统,从而鼓励玩家做出理想的行为决定。

策略

在马里奥和蘑菇头的例子中,奖惩系统的作用相当明显,但并不是所有时候都那么直接。我们再以塔防游戏为例。在塔防游戏中,玩家必须建防御塔来阻止敌人抵达游戏屏幕的另 一边。当敌人经过时,这些塔就会发动攻击,敌人走的总是抵达目标的最短路线。

塔防类游戏的基本机制是:

1、决定设置什么塔(游戏邦注:例如攻击力高低或成本高低等)

2、决定建塔的位置(2D平面)

以上就是玩家要做的选择,具体怎么做还是由玩家说的算,对吧?

如果你有认真看前面的内容的话,你应该知道当然不对。还是从技术上讲,玩家把塔丢哪都行,如果他已经不在乎输赢。游戏的奖惩系统鼓励特定的行为,所以实际上,玩家的选 择就是游戏设定好的那种机制。

例如,玩家可以把塔远远地放在右上角,但奖惩系统可不太鼓励。这么做的直接后果就是火力不足,敌人迅速“上位”,玩家失败。最终,玩家会意识到最佳方案是把塔放在中间 ,这样基本上就完美地阻断了敌人的前进道路。当然玩家也可以继续顽固地把塔放在角落,输了再放,放了再输,不过,老输的游戏还有啥意思呢。

这又是一个奖惩系统决定玩家行为的例子。游戏给玩家一定的选择,但玩家胜利的条件是实施隐藏在系统之后的最佳策略。

奖惩系统的基本原则

奖惩系统怎么作用于玩家的行为?请看以下模式图:

奖惩系统模式(from gamerboom.com)

开发者通过基本机制决定玩家的行为。然后,开发者设计奖惩系统来过滤玩家的可能选择,最后形成的是理想的玩家行为。

那么,这种奖惩系统是怎么设计出来的呢?答案就是,先给自己充点行为心理学的电。这门学问的先驱研究者是B.F. Skinner等行为学家,特别是他提出的操作性条件作用(条件 反射理论),是观察主体对某种系统的作出反应的行为。

似曾相识?操作性条件作用就是我在本文中所探讨的问题的研究基础。与操作性行为作用相似,游戏中的奖惩系统影响玩家的行为,主要采取以下四种方式:

1、主动奖励:以玩家想要或喜欢的东西作为对玩家行为的奖励。

2、被动奖励:移除玩家不喜欢的东西作为对玩家行为的奖励。

3、主动惩罚:给予玩家不想要或不喜欢的东西作为对玩家行为的惩罚。

4、被动惩罚:移除玩家想要的或喜欢的东西作为对玩家行为的惩罚。

根据玩家对基本机制的运用,游戏给予玩家奖励或惩罚,这样,游戏开发者得以不断修整基本机制的运用。例如,在《超级马里奥64》中,当玩家打败敌人,玩家通常会得到渴求 的金币。这就是主动奖励。另外,蘑菇头没了,也就是说玩家在这道关卡的敌人减少了,这是被动奖励。

对于奖罚系统的惩罚方面,如果马里奥掉到火山岩浆里,那么他就得哀号着、失控般地扑灭工装裤上的火焰。这是主动惩罚,即给予玩家不想要的东西——玩家希望始终把对马里 奥的控制权掌握在自己手里,而不是任马里奥自己乱来。另外,马里奥损失生命,这是被动惩罚,因为玩家希望命越多越好。

玩家行为塑造法

一开始,游戏的机制又少又简单,后来,不仅数量增加了,复杂程度也随着游戏进展呈螺旋式上升,然后奖惩系统开始变得相当复杂。因此,为了促成理想的玩家行为,清楚地理 解设计奖惩系统的基本策略是非常必要的。

再者,所有一切总是从游戏设计的核心体验部分开始。一旦你定义好游戏的核心体验,那么就可以开始设计能够触发理想行为的机制了。在此,请考虑以下普遍原则:描述理想行为。好的奖惩系统是隐蔽的。大多数开发者倾向于把注意力放在他们希望的行为上,然后设计能够激发那些行为的系统。如果只是关注这个系统本身,可能会产生混乱

,最终导致失败。所以你得详尽地描述理想的玩家行为。然后围绕你的描述构建奖惩系统。试着站在玩家的立场来想象你的行为。

调整。如果你所设计的系统没有激发玩家的理想行为,那么你可以进一步调整。当你希望玩家迅速地越过墙时,你想象过(或在做原型时看过)玩家总是撞到墙上的情形吗?这时 ,你要做的就是稍微惩罚一下玩家的撞墙行为。一点小小的调整可以对玩家的行为产生重大影响。另外,请保证观看你的原型视频,然后再研究如何让游戏激发玩家的理想行为。

反馈时间。另一个要考虑到的重点是奖惩的反馈时间是多少?时间多长你说了算,但你得根据希望玩家如何学习游戏的固有系统来做决定。在大部分游戏中,如《超级马里奥》, 反馈是立即的。“我从悬崖上摔下来,游戏马上宣布我死亡。好吧,收到。真惨,别再摔了。”

然而,在其他游戏中,通过延迟给予奖惩反馈,可以增加机制的复杂度。在策略游戏中,如《星际争霸》,玩家需要花更多时间来掌握策略,因为成败的反馈只到最后才知道。比 如,玩家在一个难以防守的地点建立基地可能只需要五分钟,但这个选择导致的失败直到一个小时后才出现。但玩家不可能立马就把失败和建立基地的地点联系起来。行为和反馈 的循环所需时间越长,玩家越难以有意识地发现其中的关系。

好的奖惩系统会让玩家产生掌握了游戏核心体验的满足感。无论是从巨龟怪那里救下公主还是打败迎面而来的敌人军队,奖惩系统可以指导玩家采取什么行动。另一方面,失败的 奖惩系统会拖游戏的后腿,让游戏看起来像是粗糙的半成品。务必协调好游戏的奖励系统,这样才能给玩家带来畅快淋漓的游戏体验,且保持玩家所想和游戏所为之间的和谐。

篇目3,Bastion开发者Greg Kasavin谈游戏设计

Greg Kasavin是Supergiant Games的创意总监,也是热门独立游戏《Bastion》和即将发行的《Transistor》的创造者。在帮助创建Supergiant Games之前,Greg曾在艺电担任《命令与征服》的制作人,并也曾是Gamespot的总主编。这是在2012年5月所进行的一次访谈。

Bastion(from supergiantgames)

EL:你认为什么是游戏设计?

GK:概括说来,游戏设计是关于创造游戏的艺术。它伴随着能够与玩家产生互动体验的系统和输入内容,并将创造出某些感受。所以这是一个开放性问题。,我想这也是你为什么会问这一问题的主要原因,对吧?

EL:(笑)

GK:显然它代表许多不同的事物,即基于你所谈论的游戏类型。让我感兴趣的是,在艺电有一个被称作“游戏设计师”的工作群体,而这类群体的级别却往往都是在制作人以下。但从理论上看这些人却是在创造所有的游戏内容。从某种方式来看是他们赋予的存在—-尽管从事实上说这应该是工程师的功劳。

EL:刚开始创造《Bastion》时,基于该提供给玩家怎样的体验,你和团队将关注焦点放在哪里?

GK:一开始创造《Bastion》时我们并未侧重哪一方面,或者说那时候我们还未拥有任何总计划。我们只是根据最终想要的结果而明确了一些较高级别的理念。我们的对话便是源自这里,这也是我们在离开艺电后从头开始讨论的一大内容。

我们早期的想法是创造一款不只是有趣的游戏。这也是我经常使用的一种表达,因为我认为乐趣很棒。这是大多数游戏的追求,但是我也认为乐趣是短暂的。因为一旦你离开了乐趣,你便会快速忘记它。

这是一种很快消失的感觉。这与疼痛感有点相似。事实上你不会去记住一些糟糕的伤痛。而乐趣便是这同一条线的另一端。

我们想要创造一款玩家直到最后都能有所感受的游戏,并能够围绕着这种感受做出相关决定;贯穿游戏去回应他们的体验。这便影射了我们构建游戏结局的方式,即你将在最后做出一些选择。

其次,我们想要以一种只能借助于游戏的方式去传达故事,因为如果我只是想要写一个故事而已,我便可以写本书或剧本之类。但是我们想要创造一款只会让别人感觉到这是一款游戏的游戏,而不像我们想要创造其它内容那样。

EL:你们是如何想着创造出一些不只有乐趣的内容,你们将如何在《Bastion》中将高级别的引导理念转变成真正具体的时刻?你是如何设计这些标志性的时刻?

GK:我认为当我致力于一个带有熟悉主题的故事时,我便会自动从一个特定的角度着手,我不知道自己可以编写一个只是关于乐趣的故事。

EL:(笑)

GK:我只是不想这么做。我认为故事的吸引力在于,它们之所以会存在是因为人们想要理解,想要合理地思考,而故事则能够通过一种简单的方式将一些无关的内容整合在一起并赋予其完整性。这是由一连串的事件编织在一起,一件事将引出另一件事,并且现在也存在有关你所面对的游戏世界的许多相关知识。

我认为在《Bastion》中会让大家兴奋到站起来的一个时刻便是,当你首次发现一个歌手并听她唱歌时。创造出与叙述者形成鲜明对比的角色很重要,我们便尝试着这么做,所以在游戏中的某一时刻,你将假设不存在任何其他人。在那时你将习惯于听到这个人的声音,而你最后期待听到的便会是完全不同类型的声音。

EL:回想起来,当去年我在玩这款游戏时,听到那首歌的确是最让我印象深刻的时候。

GK:谢谢。

EL:在游戏中你是否还想要传达某种叙述设备,但却不能以有效的方式表现出来?

GK:我能够很自豪地说,我们喜欢自己在创造故事时所做的一切事。我们是连续地创造游戏,这便意味着我们创造了最初的内容与最后的内容。而关于最后内容的理念则是始终就存在的。

因为所有的编写内容是基于不同关卡,所以我们尝试了许多内容,而内容编写一直都是较为复杂的环节。我们尝试着让每个关卡都是不同的,并尝试着各种新内容。

所以关于特定关卡我们尝试并否决了一些特定的叙述理念,就像我们编写,记录并执行了几百个叙述幻灯片,但是我们最终却采取了不同的方法。不过我并不后悔做出这么多的尝试,因为在尝试的过程中我们发现了一些更棒的内容。

但是我们的目的仍是保持一样的。这只是围绕着保证执行和编写足够明确并能够传达我们想要传达的内容。再一次的,我真的非常感激我们能够在具有可能性的环境下工作。

作为一名作家,你最大的希望便是有时间进行迭代,直到作品最终能够传达你希望读者所感受到的真正体验。这是关于交流,如果交流对象能够拿走你希望它们拿走的“东西”,这便是再完美不过了。

通常情况下,特别是在大公司中开发游戏,你很少会获得第二次机会。你必须在第一次尝试时便做到最好,也许你会收到一些反馈帮助你做出更好的调整,但那时候往往都已经太迟了。

EL:从更广的范围上来看,关于游戏设计最让你感到兴奋的元素是什么?

GK:关于游戏设计最吸引我的便是这些互动体验巨大的潜能及其作用。不管是对于生理上还是心理上。

我已经玩了很久的游戏了。但是我却一直能够看到其中的无限潜能。我对于有关游戏是否应该拥有经过授权的叙述内容这一讨论一直都很感兴趣。或者说是玩家的故事是否真的重要?游戏是否应该强加一个故事到玩家身上?

我从未看过游戏是将两个元素对着干的。我喜欢的游戏便做到了两者兼顾。它们找到了有效的方式去做到这点。我喜欢没有故事的竞争游戏,或者那些呈现出与你的多人游戏不相干的故事的游戏。

EL:另一方面,关于游戏设计过程你最觉得最让人受挫的是什么?

GK:我觉得游戏设计过程中最让人受挫,但也是最好的一个环节是尝试着创造一些真正有趣的内容。如果你费尽全力但却做不到自己预想的效果,那便会非常受挫。但之后你要想想,现在我要做什么?我该如何做到这点,我对此并不满意,怎么做才能去完善它?

我认为从根本上来看游戏设计就是一种交流形式。因为游戏意味着将被玩,如果你创造了一款游戏但是玩家的体验与你的设想完全不同,那你就会手足无措吧。

也许对于某些特定游戏来说,这样倒是无所谓。但是我们现在所说的是大部分游戏。

EL:这听起来就像是,在这种小型工作室里你就可以创造出一些真正优秀的作品了。你是否认为自己在不同的环境下也能够创造这样的游戏?

GK:我想如果在完全不同的环境下我们可能就不能创造出这样的游戏了。我们也会进行尝试,但最终可能就不是这样的游戏,但是在我们离开艺电前,我们正尝试着完成一款行动RPG游戏。我们真的在认真尝试着。但却并不奏效。只能说这种对抗力量太过强大了。

团队规模发生了变化,一下子窜升到好几百号人,你的游戏变成是由500乃至1000人所创造的AAA级项目。

但是在很多情况下这种大规模的团队也会被分割成一些较小的团队。我真的很喜欢我们现在所面临的环境,即所有的一切都是并存着,并且它们都有自己的优势。

兜了一圈我们又回到了原地,即在80年代和90年代,即使是基于较小的团队你也有可能创造出非常优秀的游戏。你可以面向一个巨大的利基市场创造游戏,那里有许多人都在玩游戏。所以创造一款只有5万人会尝试的古怪游戏也具有财政意义。

但对于这5万多人而言,这有可能是他们玩过最棒的游戏。这是一种很棒的感觉,不同于几年前AAA级游戏所面临的挑战,即创造出数千万人会喜欢的游戏。我不知道你会如何处理这种情况。

篇目4,Tadhg Kelly谈游戏设计

我们中有很多人自称为“游戏设计师”,但实际上我们却不一定是同一个群组。游戏设计并不非适用于所有公司(或者同一家公司内部的所有项目)的工作描述。它并未拥有一套标准的工具或者标准化的输出内容。与工程师或美术师不同的是,我们很难确定游戏设计的可交付成果是什么,因此我们往往看起来就像是天才或骗子。我们必须回答一个非常模糊的问题:你是否真的需要一名游戏设计师,或者“游戏设计”只是一种元素?

Game-Designer(from simpsonsparadox)

三个设计理念

在我的旅程中,我遇到了有关什么是游戏设计的三个理念。

第一个理念被描述为“建筑师”模型。在这一模型中,一间大型工作室的核心往往有一个人扮演着“火焰守护者”的角色。他是先见型领导者—-尽管他总是带领着一支专注于独立领域(游戏邦注:如战斗,机制,平衡,用户界面,内容等等)个体领域的年轻设计师,并且是作为游戏创造性见解的中心。建筑师型设计师的数量很少,并且经常被当成是游戏产业的名人。

第二种模型被描述为“制造者”。这类型的游戏设计师属于亲自动手型,他们想出了游戏理念并进一步将其绘制出来,形象化,编程并编写出收尾呼应的完整内容。不管他是独自完成这些工作还是借助了别人的帮助,他所传达出的整体印象都是一个项目最具潜力的核心。许多独立开发者都属于这一类型的设计师,并会使用像Unity3D这样的工具去创造出自己脑子里的想法。

然后便是第三种模型,即“工程师”。有些商店(不管大小)宣称他们并没有与“游戏设计”相关的角色,相反地他们拥有产品经理兼程序员,即不断地在实时项目中迭代着。在这一环境中,“设计”经常只是等同于内容(关卡,任务等等)创造,但游戏的基本动态则是由纯粹的代码所完成。所有的一切都是相互协作,游戏将会在这些任务完成后完成,但有时候这种情况永远都不会发生。

三个设计问题

基于游戏类型,所有的这三种方法将具有不同的优势,但同时它们也具有自己的缺陷。

建筑师型设计师将遭遇分离性。尽管他知道自己想要呈现出怎样的体验,但是将其转变成细节却常常是个大问题。建筑师型设计师将会因为为团队设定方向,但却因为最终原型未能匹配心目中的设想而在3个月,六个月或12个月后宣布将其抛弃而遭到其他团队成员的讨厌。在追寻特定游戏感的道路上他们将创造许多废物,许多大型试验也将消耗大量的钱财,并且最终有可能只会创造出一些平平淡淡的结果。对于建筑师型设计师最常见的批评便是他们太优柔寡断并且自尊心太强。

制造者型设计师将遭遇完全不同的问题。他可能没有足够的资本去创造游戏,但是他所面临的更大问题是会因为几棵树木而失去整片森林。制作人型设计师可能会专注于执行游戏中一些不重要的细节,但却未意识到其核心动态元素不能进行有效的扩展。或者他创造游戏的前提根本就是错误的。或者机制与美学间存在分歧。与未能考虑到细节因素去将历年变成行动的建筑师型设计师不同,制作人型设计师总是未能考虑到如何将行动相匹配地组合在一起。

同时,工程师型设计师的问题是集体思维将衍生出保守主义。首先,这听起来像是反直觉的,通常情况下更多想法所创造出来的解决方法总是更具有创造性,但事实却不是如此。这是属于开发游戏与开发软件并不相同的众多领域中的一个。在软件中,存在可明确的问题(如实用性,易用性或速度)的直接解决方法。而在游戏中,问题并不是这层意义上的问题:它们是指创造性问题。如何创造出某些有趣,与众不同,让人兴奋且能够娱乐大众的内容与创造出更棒的技术是不同的。因为工程师型设计师的集体思维往往未注意到这点,它要求在执行前(以避免废物的出现)验证理念,因此会讲所有的创造性过滤到那些适应迭代以及那些从未尝试过的内容中。这也是为何基于工程师型设计师的工作室会反复陷入制作同样游戏的问题中。

正式的游戏设计

存在第四种模型。

有些人认为游戏设计是一种新兴的形式训练。他们是那些深受游戏机制,用户界面模式,经济元素及其结果所吸引的人。他们认为游戏设计也就是着眼于游戏,观看内部机械设备运行然后将所学到的内容应用于新游戏设计中。

他们同意也相信自己的设计方法是可教学的。许多形式主义者是在学术领域进行操作,即尝试着让下一代学生去思考游戏。有些是以纯粹的机制服务做到这点,也有些人是将设计作为创造没学愿景或叙述体验的基础进行传授。形式主义者是基于实用主义和哲学性去看待游戏,即作为基于技术或没学以外的动词和村换等组建而创造起来的交流与表达语言。

正式游戏设计师的潜在价值是作为一名译者。正式游戏设计师将负责吧建筑师的高级概念转变成有意义的机制元素,在保留创造性方向的同时为工作室剩下大量时间于金钱。正式设计师将通过评价制作人的理念和原型去帮助他们,并识别早前的缺口然后挑战他的假设。正式设计师将提供给工程师方向去打破他所深陷的周期,并有可能将其带向不同的领域。

从理论上看

当于正式设计师一起吃饭时,我们会激烈地讨论我们方法的细节。餐巾纸将变成临时设计文件,我们将在上面为游戏的分子或机制模式拟定电路般的图标。我们将讨论动词和符号,睡迟和发射器,演员和条件规则,我们将粗略地达成共识。这里的问题,也是关于正式游戏设计最大的批评是,所有的这一切都看起来像是废话。虽然提到高级概念,但废话就是废话。

答案其实很标准化。被拒绝的设计与创造性控制具有很大的关系,但最重要的还是输出内容的质量。例如游戏设计文件的历史便是一个可耻的故事或者说是写得很糟糕的《圣经》,偷偷交给工程团队然后让他们独自去思考应该怎么做。因为没人知道该在设计中寻求什么,并且这里总是存在许多修补空间,因此会出现各种废物。缺少对于早前重要问题的可靠答案将把廉价的设计时间变成昂贵的代码和图像创造时间,这也是为何游戏设计未能得到尊重的原因。

为了让正式游戏设计能够帮助解决问题,它必须变得不再那么秘籍且是收到交付内容的驱动。世界上的其他人将不会在做些来学习我们的辞典,所以我们应该明确如何在所有人都能够轻松找到的方式下去传达设计。如此设计的价值也将清晰可见了。

篇目5,Rich Hilleman关于游戏设计的深度探讨

Rich Hilleman是艺电的首席创意总监。他是艺电最早的雇员之一,并因为帮助创造EA Sports(包含《John Madden Football》, 《NHL Hockey》,《Tiger Woods PGA Tour》在 内的游戏品牌)而声名大噪。以下是2012年4月对于Rich的一次访问。

EL:在艺电的29年工作生涯中你参与过哪些游戏的创造?

RH:我所致力的第一款游戏名为《Chuck Yeager’s Advanced Flight Simulator》,之后又改为《Chuck Yeager’s Advanced Flight Trainer》。那时候我们与Lucasfilm以及其 它公司也共同致力于其它几款模拟游戏。我们创造了包括《Ferrari Formula One》(一款有关Indy 500的游戏)在内的几款赛车游戏。我们创造了《Road Rash》。我还创造了 《Populous》最初的Genesis版本。我们面向了Genesis分别创造了《John Madden Football》和《NHL Hockey》的第一个版本。还创造了《爱丽丝梦游仙境》。

EL:参与了这么多经典游戏的创造真的是太棒了。

和往常一样,我也将问你同样的问题,你认为什么是游戏设计?

RH:我觉得游戏设计是组合各种游戏组件的过程,并为玩家创造出他们想要的体验。而这里也存在许多分歧。就像有许多人喜欢创造非常规范的体验。我曾致力于《Winged Commander》系列中。我们提供给玩家选择,但是却并未给予他们过多选择。显然在《质量效应》中我们也未给予玩家足够的选择。

Rich Hilleman(from pcgamer)

这些游戏的设计师都是着眼于玩家想要怎样的游戏体验。他们希望你能够做出一些选择,但是他们也希望你能在一定范围内操作,如此他们便能够为你创造出丰富的体验。

范围的另一端是体育类游戏,即为那些脑子里充斥着各种奇思妙想的人创造工具去帮助他们实现这些想法。有时候这具有很强的针对性:他们想要成为一个特殊领域中的特殊玩家 。而其它时候,他们会想要将其当成是辅助自己想象力的工具,去实现那些你不能预先描述的内容。

对于我来说,游戏设计既是整合一边视角的过程,也是装配工具让玩家能够从另外一个视角出发的过程。

EL:我认为体育类游戏真的是个有趣的领域,因为这是一个特殊的模拟领域。

RH:一点都没错。

EL:创造了这么多体育游戏,作为《FIFA》或《John Madden Football》的设计师的工作与Seth Marinello创造《死亡空间》的工作有什么不同?

RH:他能更轻松地进行构想,而我却很难做到这点。在Seth所面对的情况下并不存在准确的答案。玩家不知道这到底是什么,他只知道自己喜不喜欢。在这种特殊的情况下,Seth 的工作便是创造带有适当频率的体验,即能够有效影响玩家去创造情感故事,并让他们会随着时间的发展而加深对于故事结果的好奇。

大多数情况下在体育类游戏中,玩家会认为自己已经知道游戏是关于什么了。他们以为自己清楚了游戏故事。而你的一大风险便是可能对这种情况造成消极影响,即你将以某种方 式避免玩家意识到自己所追寻的故事,或你会把自己的想法强加在他们身上。

而人们所谓的自己了解体育的想法正是促使这一工作变得更加困难的两个特征。一个特征便是他们的想法是完全不可能的,而另一个则是这通常都是错误的想法。在现代美式足球 中,基于现代环境玩游戏的职责便是一边操控11个玩家,一边了解情况并做出准确的决策。

几乎没人理解这一点。意思是,如果我让你控制玩家,你便需要理解持续进行的游戏,并理解如何接近你所扮演角色所处的多个位置。如果你在《Madden》中的角色是防卫者,即 要在不同玩家间转换着,这便意味着你必须了解所有的这11个玩家,而不只是其中的一位。

所以这是一个复杂且现实的问题。如果我让你去解决问题,你便只会遭遇失败。所以我们的工作便是提供你认为对但事实却不对的内容。这将带给你真实感。这也等于我所谓的“ 尘埃”措施,即使微小但却能够构成特定且不同的体育特征,并与你所不了解的内容结合在一起:教授一些你之前并不知道的体育内容。

这似乎就足够了。然而问题在于这是个不断变化的目标,而我们每一年都需要去完善它。

EL:你是在何时开始遭遇真正的认知摩擦,即关于在体育类游戏中创造真实存在于现实生活中的功能,并看着它不能满足人们对于体育的期待或幻想以及他们的反应间的摩擦?

RH:我并不是从体育中学到这点,而是从飞行模拟器中学到的。有趣的是,我是通过创造飞行模拟器以及驾驶模拟器才走向体育类产品。

这便意味着我在此的观点很大程度是受到创造飞行模拟器的经历的影响。当我们在创造《Chuck Yeager’s Advanced Flight Trainer》时,比起《我的世界》的飞行模拟器,它拥 有当时较不迂腐但也较不清晰的飞行模拟器。我们同样也要基于4倍的帧率而运行,并需要考虑驾驶飞行人员。

我从中学到了什么?显然因为我经常中途离开并犯其它错误,所以我能学到的并不多。我们尝试着创造一个F-16模拟器与《Falcon》竞争,当《Falcon》发行时,它也伴随着一份

160页的手册紧随其后。我不知道你们是否记得,但是为了在《Falcon》中发射一枚导弹,你就必须做7件事。你必须明确目标,瞄准雷达,限制导弹的探头,固定该探头,确定探 头已经锁定了,锁定雷达图像,然后武装起来并发射导弹。

EL:这听起来就像是真正的模拟。

RH:确实如此。不过说实话,在《F-16 Combat Pilot》中,我们花了数百万美元去训练这些人。如果我给你一款游戏让你做F-16要求你做的所有事,你会怎样?首先,你肯定什么 都不会做。其次,这种体验一点都不有趣。在F-16的现代空战中射击另外一家飞机:这完全是一款雷达游戏。屏幕上只有少量信号,我将瞄准这些信号发射导弹,然后这些信号便 会消失。

但是人们真正想要的体验是像《壮志凌云》的汤姆克鲁斯那样。他们想要扣动扳机并射下目标,所有的一切事物都处于可视距离中,这就像是一场真正的对决。

现代喷气机战斗与这并不相同。但这并不意味着这里没有玩家想要的体验。所以我认为这是“事实”与“传奇”相矛盾的经典例子,因为这正是人们想要的。

我们所发现的正确做法便是给予玩家比他们想要的更加真实的汤姆克鲁斯般的体验。使用真实的导弹和真实的飞机。也许它们的速度会一样快:如此玩家便能够在游戏环境中追踪

并感知它们间的不同。

但是我们并未让玩家基于不同的战术飞行。我们并未让他们飞行。我们并未让他们基于非常真实的方式使用武器系统。我们并未让他们基于苏联所采取的协调方式使用雷达系统。 最重要的是,在20世纪80年代和90年代间,如果你驾驶的是喷射式飞机,你便不能够发射导弹。那时候的导弹是从地面发射的。你的工作只是驾驶飞机,而由别人发射导弹。所以 很明显这是个不让人满意的表达。

当我们走向体育类游戏时发现,我们已经沿着这条路走了很久。我们也曾因为呈现太过真实的内容而犯错。

所以我们需要继续解决该问题。我认为直至今日《Madden》仍是一个问题所在,即《Madden》很难,足球也很难。将其结合在一起完全是不可能的事。所以关于《Madden》的新玩 家问题便是我们每年所致力于的问题。我们并不能有效地解决它,但是我们却一直都在为此而努力。

Rich Hilleman(from edge-online)

EL:听起来创造一款有趣的模拟游戏的关键是在于传达好莱坞级别的传奇而不是真正的模拟内容。

RH:其实真正的关键是明确你所尝试创造的是关于别人脑子里的想法,而不是你自己的。如果游戏不能有效反应他们脑中的现有环境,那么内容是否真实也就不再重要。

真实性是基于用户的体验而不是现实。体育也是如此。它看起来好像所有的模拟,所有的内容都与现实世界相关联,这便是人们对于它们的想法。

EL:我和Michael John曾讨论过,当他在训练设计师时,他会教授他们什么是“玩家的思维”,他会跟他们说“我会在每个句子开始时才听你说话。”这与你在讲述模拟游戏的时 候很像。说实话,在所有电子游戏中,它们都不是关于客观地找出事实。而是关于明确玩家脑中的想法,并帮助他们实现这些想法。

RH:讽刺的是,尽管我们可能不喜欢某些内容,但在特殊的模拟游戏中,我们却是扮演着真正的行为艺术家的角色。而当你是个DJ时,不管你是否做得对或者不管用户是否在跳舞 便都不重要了。

我认为在我们的例子中,这便是关于游戏如何运行。我们在寻找来自用户的反应,即表示我们触及了他们对于游戏中故事发展的真实感与期待感。他们在绘制图像并填补空间,这 是我们不能够影响到他们的想法。他们在体验我所不能给予的。模拟的威力便在于某些内容其实已经存在于人们的脑子里了。

EL:作为首席创意总监,你的工作是否有趣。

RH:(笑)你还是不知道我在做些什么。

EL:是的,我仍然不清楚作为首席创意总监的你的主要工作是什么。

RH:它们之间也存在着一些矛盾,而我认为最可行的事主要有三个。首先便是明确我们公司拥有高质量的设计人才和制作人才。

我致力于确保我们能够在大学项目中投入足够的时间与空间去培养自己所需要的这类型项目中的人才,然后再考核哪些人才是真正合格的。之后再面向这些人进行二次投资,以确 保他们能够给我们公司的未来做出贡献。这便是我们所做的第一件事。

我们所负责的第二件事便是有关游戏设计图像的状态。举个例子来说吧,就像团队中的Sandy之所以会和我们共同致力于现在的工作中是因为我相信,比起其它市场,免费游戏模式 将在中国市场取得更加快速的发展。这是我们对于该市场的理解,而这将直接影响着我们是否能在美国市场取得成功(游戏邦注:即在中国市场成功后在美国市场仿效同样的模式 )。

对于我们来说这真的是件奇怪的内容,但却是关于最基础的游戏设计。所以我认为确保游戏具有意义的一方面内容便是拥护设计师的角色,而我们对于设计原则和新事物的倡导将 会体现在游戏世界中。

EL:作为游戏设计师意味着你们和许多你们尝试着培养的人才(艺电或游戏产业在大学或其它领域所培养的年轻游戏设计人才)有许多不同之处。你想要塑造怎样的现代游戏设计

师角色呢?

RH:一个像Seth那样创造射击游戏的人,一个创造出像《模拟城市》的模拟类游戏的人,一个创造了一款社交游戏的人,一个创造了一款社交游戏的年轻女性,一个创造了一款手 机游戏的人,或一个创造了一款AAA级主机游戏的人,但是不管是怎样的类型,你们所面对的问题类型都是不同的,因为你们的用户是不同的,你们的盈利系统是不同的,你们的分 销渠道是不同的,人们的游戏频率和持续时间也是不同的。

而他们间的更多共同点在于与长期用户之间的高指标指向型关系。如果我尝试着在今天的大学项目中完成一件事,它可能是关于如何掌控你的产品在传达玩家如何游戏的信息。而 你需要做的便是改变这些数据,期待这些改变,并向团队其他成员做出详细解释。

很长一段时间,或者当你与我一起做事时,你会发现在缺少音频设计师的公司里,设计师其实过着公司中最底层的生活,因为在几乎每个团队中,他们与美术人员的比例是30:1, 与制作人的比例是10:1,与工程师的比例是10:1。他们唯一可能超过的角色便是音频设计师,即有可能是3:1。

EL:有人曾告诉过我如果想要在艺电做自己想要做的事,那就想办法成为制作人。

RH:你如果想要获得控制权,那么制作人的头衔便能够帮助你做到这点。

不过我认为这种情况也发生了变化。这并不是说设计师是完全受控制的,我认为随着人们对于遥测技术和指标的兴趣的不断提高,现在的我们能够更好地评估设计师这一工作了。 我认为之前所存在的问题是关于许多公司和大多数业务都是在设计师推出内容时,也就是每隔18个月左右才能对其展开评估。而其它有关设计师的影响力的元素却被彻底忽视了。 只有你能够真正剖析一件产品,你才能理解设计师所做的以及人们强加给他们的误解。

但是我认为真正有趣的是,如果你拥有指标,如果你拥有遥测技术,如果你与用户维持着长期的活跃关系,你便能在三周内判断一名出色的设计师。而我认为真正发生改变的是设 计师能够通过某种方法向用户传达自己多优秀,并解释为什么你可以在他们身上找到其他团队成员所不具有的特性。

这将成为能够在短时间内理解并衡量的产品组件。

EL:这绝对是最标准的评估。我认为通过在《龙腾世纪传奇》中的体验,我们便能够获得有效的理解。这里还有很大的发展空间。

RH:关於这点的部分分析(当你获得数值时)并不意味着你知道它们代表着什么。我认为我们还要经历许多过程。

EL:在过去几周通过与各种指标的人士进行交谈后所留给我的最深刻印象是,进行A/B测试的人真的很优秀,并也因此得到了回报。当你问他们,有多少测试是没有效果时,他们会 回答大多数。你所测试的60%或70%的东西是没有效果或不会做出明显改变的。

我真希望自己在12个月前便清楚这点。那么我便可以面向自己的产品做出100个更好的决策,“嘿,你知道吗,70%的情况下我们可能看不到任何结果。而当我们看到1%的变化时, 我们便算取得了巨大的成功。”

RH:我认为这也是为什么设计师们开始取得了一些进步,一方面他们能够解释更多情况,另一方面他们理解何时才能做出改变。当你告诉某人“我们将对这些数据做出3%的改变, ”你便会做出这些改变,这就像是个神奇的法术。对于同个房间里的其他人来说,你所做的就跟魔法似得。

如今你能够向人们解释原因,因为通过预测,你已经找到了一些真正的原因。但是对于大多人来说,他们仍然不愿思考足够的细节去理解一件可预测的事。

你可以提前预测某些情况,但是当你连续三次这么做时,制作人便会说:“不要管他。”(笑)“我不知道他在做什么,但是你们肯定不知道他是怎么做到的。所以不要管他。”

如果你想要描述设计师最想要的最终状态,那可能会是:“不要管我。”(笑)

EL:你认为现代游戏设计师所面临的最大挑战是什么?

RH:我不认为这些挑战发生了多大改变。设计师们还是面临着同样的问题。从根本上看来,玩家想要知道怎样才可以不用为游戏花钱。在过去,各种盗版行为成就了玩家的这种想 法。

我认为在某些方面,我们程式化了这种情况。免费模式真的是这种过程的一种格式。这便意味着让消费者付钱仍旧是最困难的事。

过去在艺电的执行制作人培训中我曾说过:“电子游戏中最复杂的工作是什么?”制作人便会起身回答:“制作人的工作”;工程师会说是“工程师的工作”;而设计师也会说是 “设计师的工作。”我想说这问题很简单呀,所以我便对大家说“给我5块钱”,或“给我60块钱”。

我绕着房间走了一圈,但却没人愿意给我60块钱。所以答案便是,“我想我们已经明确了现在电子游戏中最复杂的工作:让某人给你60块钱。”

面对着各种组织,我认为一家公司如何成功完成自己的工作都是有意识或潜意识地围绕着得到报酬的过程。如果作为设计师的你认为可以在未来忽视自己如何得到报酬的过程,那 么围绕着这一想法去调整自己的设计努力才更加重要。

对于曾经设计过的第一件产品,我在设计中所做的第一件事便是描述我需要六张截图呈现在包装背面,因为这是消费者决定是否购买我们的游戏的一大重要元素:这两张截图以及 它们所传达的内容。

25年前,我决定围绕着最难完成的任务,即付费,去创造自己的产品。我认为这是再合适不过了。如果你是一名设计师,并认为自己应该避免这一问题,我想你将不可能长久地承 担一份工作。

另一方面,那些理解它并清楚你是如何通过A/B测试去获取更高收益的人将发挥更大的作用,甚至是会被当成制作人一般的存在,即使事实上他们并不是。(笑)

EL:关于今天的游戏设计最让你惊喜的是什么?

RH:你应该听过我之前所开的一个玩笑,即嘲笑自己有多老。我已经很老了并在这个业务中待了很长一段时间,但是关于我们是否能够成为一种受法律保护的艺术形式却仍是不确 定的事。这是个让人困扰的问题。

当回首过去,我们会发现自己基于各种方式经历着文化上的变革。其中一种方式便是越来越多人开始玩游戏了。他们只是这么做着,这并不是潜意识的行为,他们也并未真正在乎 这种行为。

这并不代表他们想要变成那些一天待在房间里20个小时吃着立体脆(游戏邦注:百事的一款食品),甚至都懒得去上厕所的14岁青少年。但的确是越来越多人接受了游戏。这是第

一点。

第二点,越来越多社会上的其它部分开始着眼于从游戏中寻找解决问题的方法。而对此我感到了稍许的焦虑,因为这是他们在看到我们之前很长一段时间所拥有的问题。这让我开 始担心我们不能真正解决他们的问题。我不认为我们能够独立解决教育系统的问题。我不认为我们可以独立解决企业教育问题。

但是我们是否能让事情变得更好?当然。不过我们也并非灵丹妙药。并不可能治愈癌症。

但看到现在的人们将我们当成是一种解决方法而不再是问题,心里也确实舒坦多了。而需要明确的另外一个事实便是,现在你可以更轻松地触及更多用户了。

之前在我参加PAX East游戏展时,有个人对我说道:“我是计算机科学编程专业的大三学生。我非常喜欢游戏。我该如何做才能让人们注意到我呢?”我问他:“你制作了多少游 戏了?”他的回答是:“一款都没有。”我说:“那你就先制作一款游戏。没有什么比一个人想要创造游戏来得美妙了。只要你有这一想法就不会有什么能够难倒你。在今天你可 没有理由不去制作游戏了。我想你能找到的唯一借口便是你不愿进行尝试。”

现在与7年前不一样了,那时候的你即使不能创造一款AAA级主机游戏也没关系。现在你拥有手机,网页,下载和免费模式等等方法。你还能创造社交游戏。所有的这些产品领域的 准入门槛几乎为零,5000美元和一定的关注度都能让你成为这些业务中的佼佼者。

这种情况一直在上演。就像《Realm of the Mad God》便是由两个人独立创造出来的游戏。尽管他们都非常优秀,但是仅凭两个人之力真的很厉害。

我们大多数最优秀的手机产品都是由一个人所完成的。在今天你可以做各种尝试。除非你不想做。

如今同时发生了两件事。第一件事便是我们基本上拥有了完整的二代游戏玩家。这些人是伴随着玩家父母而长大。而现在的他们也开始思考制作自己的游戏。他们将采取我们可能 不理解的方法进行创造。我认为如此低的准入障碍以及如此庞大的潜在游戏创造者的结合意味着游戏产业的发展将越来越明朗。

不管怎样,只要你真正喜欢游戏,这便是个很好的时机。

EL:我还记得我们家买的第一台家庭计算机,它是售价3000美元的Apple LC II。

RH:哇。

EL:那时候我便可以使用HyperCard去创造自己的第一款游戏了。而在今天,只要花200美元你便能够得到一台足够强大的计算机,并免费使用各种软件将一款游戏免费呈现在数百 万人手中。

RH:在短短的六周时间里,你将从没有电脑,什么都没有摇身变成拥有一款2万多人在体验的游戏创造者。这在今天是绝对有可能的事。

换做在1984年,这是人们不可能想到的情况。谁会相信会出现大批玩家去玩游戏,更别说我能快速地触及这些玩家。

这不再是一个关于6502条装配线的问题。我的意思是你可以轻松利用Simple Basic完成许多任务,这是来自微软的一款免费软件,能够帮助你创造出8位体质量的投币式风格电子游 戏。

基于该技术所创造出来的游戏还有很多。再一次地,这也不是限制你创造出优秀游戏的阻碍。只有你自己才是影响自己能否创造出优秀游戏的真正元素。

EL:这才是你的真正动机。

RH:没错。我有自己的小孩,而他们最不想听到我说的便是关于生活中有80%是关于2件事:40%是作准备,而40%是完成。中间的20%并不是什么大事,但却是所有人投入最多时间在 做的。

我们都知道这点。你应该遇到过一些才能平平之人不断咬牙坚持着,希望能完成你所不看好的一些事。你也有可能遇到过一些从未真正完成某些事的聪明人。这两种情况是完全不 同的。在如今的时代里,拥有这些特征的人是没有理由不会去表达自己的。我认为这具有很大的差别。

所以我真心希望他们能够创造出一些优秀的游戏(笑)。我也相信来自中国,东欧,南美,甚至是东亚/印度等国家的人所创造的不同形式的游戏也会非常有趣。日本,美国和英国 论坛也正是如此演变成为世界性论坛的。

如果是在5年前,你是否能够说出来自这三个国家的游戏设计师的名字?

EL:并不能。

RH:是的,即使能也只有少数几个。也许还有一两个来自法国。

EL:没错。我想到了育碧的成员。

RH:让我吃惊的是,直到5年前,德国仍是一个每年拥有10亿收入且没有任何本土游戏设计人才的市场(除了一些基于殖民者风格的迂腐的桌面游戏)。该市场中的一切别人的内容 都是由外国人所创造的。如此看来他们并不能支撑自身国家游戏的发展。意大利也是如此。这些国家虽然拥有较深的文化底蕴,但却不能创造出属于自己的本土论坛。不过现在他 们都做到了这点。

EL:所以全世界市场关于游戏发行渠道所使用的方法……

RH:这里有许多不同的经济模式。

EL:没错。是否在今天使用免费游戏模式与在80年代末/90年代初使用自动投币模式是一样的?这种类比是否有意义?

RH:我认为这更加接近于1981年或1982年前的计算机游戏。我会说大多数发行于1982年前的计算机游戏都是通过复制从一个人手中传到另一个人手中。我觉得这与80年代的重金属 磁带无异。地下重金属摇滚乐的传播的主要机制便是一个人用磁带录下另一个人磁带上的音乐。

我认为这便是免费游戏所做的,它抚平了传播系统中的所有摩擦。而现在存在的问题是,你该如何从潜在的亚文化中获取盈利?我听过一个笑话是,在1986年或那段时间,你可以 购买三张金属乐队的唱片和一件T恤,这便是那时可出售的商品的总和。显然,在今天这些商品的管理变得更加完善了。它们已经找到各种不同的方式让消费者掏腰包了。

我认为接下来免费游戏要做的便是创造其它能让消费者花钱的方式。我认为《愤怒的小鸟》获得利益的各种渠道还未真正与现今电子游戏挂上钩。实际上,我认为今天电子游戏的 主要收益来源还是授权。

EL:是的,我甚至在加州博览会上看到《愤怒的小鸟》的赠送玩具出现在米老鼠的旁边。

RH:这是一个受利益所驱动的领域。我们已经陷入了这种文化中。

EL:你会在技能上辅导并帮助年轻的设计师们,并将他们带到艺电,你认为他们如果想成为一名商业游戏设计师将会面临的最大挫折是什么?

RH:我们所从事的是一份有关幻想的工作,这意味着许多进入我们这一业务的人都是真心想要成为电子游戏设计师的人。你已经见过他们中的一位,也就是Blade Olson。他是我见 过的第一个拥有“我该如何创造电子游戏?”的意识的人。

所以如今我们可以在产业中看到许多这样的人。而他们真正的魅力在于对这一业务的感激以及对于自己每天工作的热情。

不过坏消息便在于,他们在进入这一业务前并不清楚自己将做什么事。当你投入了很多时间于你所构造的幻想中,但却遭遇到完全不同的现实—-可能没有比较好或没有比较糟,只 是不同而已,这对大多数人来说都具有很大的打击。

我尝试着确保从业务的角度去谈论业务的运作,而不是用户的角度。如果你是一名用户,你便会想:“这只是关于制作优秀的游戏。你创造了优秀的游戏,他们都是有效运作。” 但事实上却不是如此。

我尝试着让他们清楚决策制定过程如何在公司内部发挥作用,即关于他们如何决定怎样的游戏可行怎样不可行。当你进入这一业务3年,并重新坐下评估之前的决策是否可行,我敢 打赌你应该不会想要继续创造同样的内容。

所以我认为对于人们来说最困难的教训便是分离幻想与现实。奇怪的是,这正是一种游戏设计学习机会,因为在创造模拟游戏时你会去探索同样的幻想。

当看到现实世界与你的期望相反时,你的能力将受到巨大的打击。

EL:你能分享在自己的职业生涯中所吸取的一些经验教训吗?

RH:我想应该是关于想象力的治理。这听起来很简单也很明显,即关于如何编造事情。但实际上这并不是我的意思。

治理想象力并不只是关于你自己的想象力,还有关于其他人的想象力,关于那些你要与之共同创造产品的人的想象力。明确该创造怎样的产品的过程是创造一件产品较为交单的组 成部分。让其他人看到你所看到的,理解你所理解的,保护你觉得需要保护的,并珍稀并投入于该投入的内容中。然后让组织予以理解,让销售组织予以理解,让其他合作伙伴能 够予以理解,并最终让你的用户能够予以理解。同时理解所有的这些想象力并明确那些并不存在的现状真的非常可怕。

这便意味着你的想象力很重要,但是你在理解其他人的想象力方面却有待加强。我认为大多数设计师所缺失的便是对于其他人的了解。创造我们自己想要创造的似乎是一种自私的 努力。当你让别人掏钱去实现你自己想要创造的东西时,这真的是个非常低劣的把戏。

不幸的是这只是半个把戏。还有一半之后才会发挥作用。而能够让它们发挥功效的元素便是其他人的想象力。

我认为设计师拥有一个非常妙且非常快速的方法去做到那点,去满足他们对于自己想象力的追求,甚至能够满足用户对于游戏体验的追求,但却会因此忽视了其他人。他们会经常 因为这样而沮丧。

我便遇到过许多优秀的设计师不能有效地做到这点。David Jaffe便是一个典型的例子,他是真的很爱自己的玩家,真的很推崇自己的看法,但却无法忍受过程的其它部分,并觉得 这阻挡了自己的去路。

我想Peter Molyneux也是这么做的。Criterion的Alex Ward也做过同样的事。还有像Will Wright等人,在自己表现得最出色的时候他们便会避免做到这些,但是当在表现糟糕的时 候,他们便想着如何去操控它们。

所以谁是最擅长做到这些的?我认为Cliff Bleszinski便能做到有效的平衡。

我想其他人也在努力让别人能够为自己做到这些。就像Will Wright需要Lucy Bradshaw。David Jaffee需要Shannon Studstill。有时候这些人也是不完全的。他们还需要其他的另 一半。

EL:这与Michael John所拥有的想法很像,即他认为设计领导者并不一定是拥有最棒理念的人。有些人总是能够激励一群人同时朝着一个方向前进。

RH:这是关于激励与沟通。

但这也是一种危险。创造性努力中的模糊性具有一定的价值,这并不需要做出太明确的定义。所以我会说“我们将创造出世界上最出色的电子游戏。”但只是如此。而你和我在脑 子里看到同样的事的可能性是多少?也许是零。(笑)。

但是另一方面,如果我说我们将忽视我们可能拥有不同想法的事实,那么我们同时感到高兴的可能性又是多少?有可能非常接近100%。

所以这里的挑战在于,想象力到底需要多具体?它会表现怎样的同一性?你会规划出怎样的过程?如果你将与一个团队的成员共同创造某些内容,那么有时候你关于声音该如何 设置的想法可能便不会是最佳想法。

当你说出自己能够想出的最棒的声音,那么团队成员对于该想法的理解将远远超出你向他们传达的能力,更别说真正理解你所说的。

所以真正有趣的是:你的想法有多具体以及你是如何明确进行传达与你如何努力传达自己想要用户获得的体验以及你希望创造情感体验的人能够为自己创造这样的情感体验之间的 比较。

有时候这会导致一种混乱的局面:因为你从不晓得如何统一想法,所以你最终只能创造出具有7个不同方向的产品。我只能说这既是一种糟糕的制作也是一种糟糕的设计。但如果能

够做好这点,最终结果便会如魔术般让人惊艳。它将成为你们所有人能够想象到的最棒的产品。虽然是如魔法般神奇,但却是真正的存在。让人惊讶的是,如果你采取了正确方法 并与正确的人合作,你们便能创造出让人满意的结果。

篇目1,篇目2,篇目3,篇目4,篇目5(本文由游戏邦编译,转载请注明来源,或咨询微信zhengjintiao)

篇目1,The Game Design Canvas: An Introduction

by Brice Morrison

Do astronomically successful games happen by chance, or can their approach be systematized? Are the games that make us laugh, gasp, and enrich our lives results of the developers getting lucky, or careful decision making? Is there a way to analyze successful games to understand where their strengths and weaknesses lie, and then apply them to your own games?

I believe that the answer to these questions is yes: a game’s design and development can be mapped out, studied, and perfected in a reliable fashion. Successful companies like Nintendo, Valve, Zynga, and Blizzard would agree. Legendary game designers like Shigeru Miyamoto, Will Wright, and Peter Molyneux would likely agree as well. These companies and developers have found ways of looking at games that lets them consistently crank out hits year after year after year. By the time you get to the third and fourth blockbuster, it is no accident.

Through analyzing countless independent and corporate titles over the course of the last several years, I’ve come to believe that there is a standard way of designing and studying games. Changes in the industry don’t disrupt it. New companies, new genres, and new controllers don’t change it. Independent or corporate, these rules are the same. These are systemic laws that are immutable. Developers ignore them at their own risk.

This approach is called the Game Design Canvas. It is made up of five different components: The Core Experience, Base Mechanics, Reward and Punishment Structures, Long Term Incentive, and Aesthetic Layout. The Game Design Canvas’s goal is to provide a powerful analytical and planning tool for developers, independent and industry veterans alike. All games have aspects that can be represented in the Canvas, and through it, it is possible to analyze the strengths and weaknesses of any game for the purposes of study and improvement on future projects.

This article will serve as an introduction to the concept of using the Game Design Canvas for developers who aren’t familiar with it. From there we’ll focus on the most influential part of the Canvas, the Core Experience.An Overview of the Game Design Canvas

The Game Design Canvas is a tool that can be used to analyze and formulate games and their development. By using it to firmly define the component of both successful and unsuccessful game titles, we can gain a great understanding of what makes the game tick, or what caused it to fail. Once we understand that, developers can use the Canvas to find a design approach for their own games.

The Game Design Canvas can be used to break down the systems that comprise different games and determine the aspects that make them what they are. As stated, the Canvas is made up of five major components:

Core Experience – What is the player experiencing as they play the game?

Base Mechanics – What does the player actually do?

Punishment and Reward (P&R) Systems – What behavior within the game is encouraged or discouraged?

Long Term Incentive – What causes the player to continue to play?

Aesthetic Layout – How is the setting represented through sight and sound?

In future posts we’ll be applying the canvas to several game titles as illustrations, as well as delving into the specifics of each of the five components. For now, let’s get started by going into the most important of the five components: the Core Experience.

What is the Core Experience

“I hear, and I forget. I see, and I remember. I do, and I understand.” – Confucius

At the center of every game is the Core Experience. This is the feeling that the game is trying to evoke, the .inner emotion that the player is going through as they play. The Core is vitally important, because conveying an experience is the purpose of every game. Games that have a well defined Core Experience and are able to bring it to fruition more often enjoy critical acclaim and financial success.

Examples of solid Core Experiences can be any moment or period of time the developer chooses. It can also be an abstract notion or feeling.

Fight as a soldier in war (Call of Duty; example below)

Be a healthy person who is getting in shape (Wii Fit)

Feel like a clever adventurer (Legend of Zelda)

Be a sociable farm tender (Farmville)

Live the life of a different person (The Sims)

Be a vigilante or a criminal (Grand Theft Auto)

All of life is an experience. Games specialize in taking a slice of life (as narrow or wide as the developers likes) and then allowing the player to feel and exist in that slice for a period of time. Books, film, and other media attempt to do the same thing. They drop the reader into a short lived romance, or allow the viewer to observe a struggle. Games go one step further in demanding that the player take action and be a part of the experience.

A game that succeeds in delivering its core experience will be able to predict how its players will describe it before they open their mouths. The development team will be intimately familiar with their desired Core Experiece, and their decisions during production will reflect that familiarity. Games developed with a strong loyalty to their Core Experience are admirable works of art.

History of Core Experiences: From Chess to First Person Shooters

We’ve stated that a good Core Experience can be a sampling of anything that can be described in life. Of course anything is possible, but there are trends and favorites in our industry that have shaped the direction of games up until the present. Let’s take a quick detour through the history of Core Experiences in order to better understand where we stand today.

Ancient games and sports have always had games which expressed the concept of conflict. Chess and fencing are both examples of traditional games long before the age of the computer that bared many resemblances. Each of their Core Experiences are dedicated to struggle; chess emulated the strategy of war, of making difficult decisions and forcing sacrifice to attain overall victory. Fencing recreated the feeling of one on one combat found in the medieval battlefield.

Likewise, game-like activities such as dancing or music are as old as writing. Far fromconflict, these types of games were influenced by harmony, simulating the feeling of cooperation and communication with another. The fiddler follows the drummer and they play back and forth. The lead gently pushes his follow to and fro, twirling and gliding around the ballroom without exchanging so much as a word. The Core Experience was one of enjoyment of another’s synchronicity, of two or more people becoming one.

In the 70’s, when computer-aided video games came into being and the coin-slot industry was taking off, games were focused on the experience of a challenge. Man versus the machine and man versus himself. Pong and Space Invaders beckoned the player insert one more quarter to prove his worth. Almost every game boasted a high score list, an opportunity to display skill and mastery. The Core Experience of games from this age was one of mastery over self and over a well defined challenge, of competing against the history of players before. So strong was the influence of this Core Experience over the coin-slot industry that many games retained high score counters well into the 90’s, long after their designs had rendered them useless.

In the 80’s and 90’s, games began to branch into broader Core Experiences than the player’s personal high score. The most popular role playing games such as Final Fantasy or the Legend of Zelda were used to tell stories greater than the players themselves. They whisked the player away to hear the harrowing tale of knights and peasants, of adventurers from past and future worlds. In this age of games, the Core Experience was to emulate the tale of another. Developers did this by developing characters, painting worlds and adding back stories (Aesthetic Layout). By broadening the possibilities of their Cores, they gave the actions of the player meaning within the fictional world of the game and took players to places they had never been before.

Since 2000, games have taken further leaps and have begun to express a much larger range of experiences. Games that follow the tradition of the 90’s to help the player feel what it’s like to live the tale of another are able to do so with much more immersion than ever before thanks to increases in technology and processing power. The Grand Theft Auto’s and Spore’s of the day appear more real than their ancestors. Water, smoke, buildings, crowds, humans, and non-humans look and sound more real than ever before, while the Core Experience remains the same. Tell a story, go on an adventure, complete the mission, save the day.

Other modern games seek to pull the Core Experience back to the player’s real life. The Wii Fit’s of the world help us improve our lives outside of the game. They provide the player with the feeling of improvement in one’s own life, of striving towards a goal that is more than a high score or a fictional tale.

Effective Core Experience Example: Call of Duty Modern Warfare 2

Call of Duty is an astonishingly profitable series. The latest title released was dubbed the largest and most aggressive game launch in terms of advertising the industry has ever seen, resulting in over 4.7 million units sold in the first day alone. Clearly they have found a Core Experience that is popular and have been able to stick to their guns, making sure that everything in the game was married to that Core.

Modern Warfare 2 has a very firm Core Experience: being a soldier in war in the present day. This is the feeling that all players should have when they play the games. Among other games in this genre, they are the undisputed winner in terms of both sales as well as critical acclaim. Everything in the game, the bombers soaring overhead (Aesthetic), the game scoring structures and weapons (P&R System), the ranking systems and promotions dolled out in multiplayer

(Long Term Incentive), all of these aspects serve to bolster this Core Experience.

At each feature, you could ask yourself, “How does this make the player feel?” The answer would be the same: they all make the player feel like they are a soldier in war.

There is no aspect of the game that deserts this, hence the title’s praise. If these fringe features did exist during the development of the game, the team at made certain not to let them survive into the final shipped product. The game screams consistency.

It is no small feat to make a player feel as though they’re in combat with terrorist organizations while in actuality they are sitting on their couch in their living room, holding a game controller. This trick of the mind is only possible by a specific and precise Core Experience that is supported by the other four components of the Game Design Canvas. Call of Duty Modern Warfare 2 represents the power and grip on players and market share of a game that is completely faithful to its Core. By being able to describe its Experience and then analyze its implementation of that experience against the Game Design Canvas, its wild success should not be surprising.

Beyond Development: The Core Experience in Marketing and Sales

The Core Experience is at the center of the Game Design Canvass because it influences each and every other aspect of the game. The game’s Base Mechanics, P&R Systems, Long Term Incentive, and Aesthetics all draw their meaning and their compass from the Core Experience. If the Core is flat or unpopular, then so will be the rest of the game. Thus, not only do development teams have an interest in the game’s Core, but the game’s marketing (or getting the word out for independent developers) also heavily draws on it.

When a game is completed and ready to be shipped to or downloaded by players around the globe, the first question that needs to be answered for the customer is “What is the Core Experience?” If someone is told that a game is “good”, they aren’t likely to purchase it based on that review alone. A player needs to know what they’re getting into so they can ask themselves if that’s an experience they’d like to participate in. Is it a ninja adventure? Is it a reading tutor? Whatever it is, the Core Experience becomes the marketing voice to sell the game. The bullet points on the back of the game’s box or on the top of each online review will be directly related to the game’s Experience.

Define the Core and Move Forward

Ultimately, a game lives or dies by a correctly chosen Core Experience, and the success of failure of its implementation through to the other four aspects of the Game Design Canvas. The Base Mechanics, P&R Systems, Long Term Incentive, and Aesthetic Layout all take root in and draw their meaning from the Core Experience. This is why defining the Experience of a game is so vitally important for development teams. It is the task that should be done first. If the

first attempt was wrong, then adjustments must be made and the rest of the project must be altered as a result. Letting any of the other four components drive the development of the game is a mistake that can lead to stunning visuals or a gripping story that mean nothing.

If the Core Experience of your game is not one that players will enjoy, then the best implementation in the world will not make it a successful title. The graphics, music, and sound (Aesthetics) could be praised in a review, but the overall enjoymnt of the game will be low.

However, if a game’s Core is well defined, everything points to creating that Experience for the player, and it is an experience that players desire, then it will be difficult to peg the game as anything but a success.

Dave is working on his blockbuster indie game title. He knows the genre, and he has a general idea of what he wants it to be about. It’s an action/adventure title about vampires and he wants the player to be able to steal blood from victims. He’d also like the player to have to avoid light in the day, and it would be a story about love and romance. Sounds like a great game!

He expresses this idea to a friend of his who is in the industry. His enthusiasm is apparent in his voice and his excitement about the idea, with the main part of the game revolving around the vampire stealing blood. But then his friend asks him…

“How does the player actually steal blood?”

Dave reminds his friend that the vampire will be able to go up to anyone and suck their blood, and that’s how it occurs. But his friend reiterates, “But what actual buttons will the player be pressing? How are you going to convey stealing someone’s blood as a vampire through pressing a button?”

Dave looks down at his shoes, realizing that although his idea may be exciting from an elevator pitch, he may have jumped the gun.

You Can’t Build a House without Bricks

Dave’s idea may be a good one, but will it come to fruition? It depends; all of his thoughts are fine ideas, but there’s no structure to them. Dave hasn ’t taken to the time to build the foundation of his game; he’s just started with random anecdotes. Odds are that if good old Dave just goes ahead and starts coding in his idea without connecting the dots first, he’s going to end up with a mediocre game that feels kind of like…well, every other game. Which is to say it won’t really feel like anything.

To begin his journey of constructing a vampire experience, Dave will at some point in the early stages of production need to think about the Base Mechanics.

As discussed in our introductory post, the Game Design Canvas is an analysis and planning method that game developers can use to map out their game’s arc, goals, and player experience. By using the Canvas, designers can structure their game around the desired Core Experience that they’re delivering to the player.

Through the Game Design Canvas, designers, developers, and players can describe and break down of the major components of any game. Last time we discussed the importance of the Core Experience, the feeling that the developer wants the player to have while playing their game. In this post we’re going to talk about the second aspect of game design, the Base Mechanics.

Let’s start with an analogy. Houses are made up of bricks. People don’t think of the actual bricks, wood, or pipes when walk into a house. New homeowners don’t brag to their friends about the kind of mortar their home uses; no, they want to focus on the finer things! They want to show off the stylish hardwood floor, the marble counter tops, or the multi-story heating. The bricks are given. If the bricks aren’t put together correctly, then nothing else matters.

In the same way, games are built of Base Mechanics. These Mechanics are the actual actions that the player performs. When the player presses a button, then there is a response on the screen. When the player moves their mouse, then there is a change in the game. When the player moves their Wii remote or whatever input device they’re using, there is an effect to pair with the cause. These interactions are what make up the game, and they are vitally important. Yet paradoxically, players tend to not think about the mechanics very much. On the other hand, to deliver a high quality title, it’s the developer’s job to be obsessed with these “bricks”.

Base Mechanic, meet Developer!

A Base Mechanic could be introduced as any pairing of player action and reaction in a game. While the player may be thinking about the game’s story, the goals of the level, or other high level components within the Game Design Canvas, what they are actually doing from second to second, moment to moment, can be described in the Base Mechanics. Without the Base Mechanics, the player does nothing.

To be a game, players must be interacting with it. If they aren’t interacting with it, then they aren’t playing a game, they’re just observing or not participating at all. Player interaction can be any number of things. For modern games it’s most commonly the press of a button, or for motion controlled games it’s the gesture of a remote. Outside of video games you have movement in sports and placing pieces in board games. All of these are examples of the player performing an action that will affect the game.

Games are symbolic. They give meaning to actions that would not normally be there. If I pick up a little wooden man and move him across the table, that action has no meaning (other than the fact that maybe be wooden man was in the way of my soft drink). However in the context of a game like chess, that action has the meaning that I am attacking my opponent with a pawn.

There are several categories of these Base Mechanics. To be able to apply them to our games, we’ll want to understand and use all types of them.

Atomic Base Mechanics

Some Base Mechanics are atomic, that is, they are the absolute smallest action and effect that can be found in the game. This is usually a single button press or gesture, but it could also be more complex depending on the game. The point is that, within the rules of that game, that action cannot be broken down any further into smaller parts.

In Bejeweled, arguably one of the most successful online casual game of all time, the player must click different jewels to swap their locations and make rows of three. For this, the Atomic Base Mechanic at work here is the player clicking on a jewel. The reaction to the player’s click is the movement of the jewels. While this game has been played for hundreds of millions of hours by players all around the works, when you map Bejeweled out on the Game Design Canvas, all those players are doing are clicking a jewel, and moving it. Over and over. This

In Wii Sports Tennis, the Atomic Mechanic is when the player swings their Wii remote, resulting in their character swinging their racquet. It is through this action that every match is played by every player.

Most games are made up of surprisingly few Atomic Base Mechanics. The two examples above have only one. Even complex modern games usually only have about 3 or 4 Atomic Base Mechanics at most. For fighting games there’s attack, defend, move. For first person shooters there’s shoot, move, using cover, and special items. In RPG’s the actions are traditionally attack, defend, use magic, and use items. These games may dress these up and build them into complex

chains (more on that in a moment), but the atomic actions the player is taking are relatively simple.

Atomic Base Mechanics are interesting because they describe the game in such a scientific way that often sounds dull. While the goal of making a game is to attain a Core Experience, how they player will feel, the actual bricks of putting that together appear less enticing than the full package promises to be. Think about how fun the following games sound:

* All you do is move a ball and try to get it into a certain area.

* You click on something and then select how you want to interact with it. That’s the game.

* The only thing that happens is you read text and select from different choices.

Not very fun, right? And yet they are the Atomic Mechanics of some of the most beloved games in history.

* The sport of soccer/football

* The Sims

* Final Fantasy, or classic RPG’s in general

This example serves to show that you can’t judge a game by a description of its Atomic Base Mechanics. That’s like trying to say you know someone after reading a bunch of facts about them. ”This person has brown hair, is kind of tall, and enjoys baking. Do you like them?” Computers can think like that, but humans need to be taken a little further. The Core Experience of a game doesn’t begin to shine through until we get at least to the next level of Base Mechanics.

Complex Base Mechanics

Atomic Base Mechanics are important, but of course games are more than running and jumping. They are running through a crowded city and jumping up on top of a building without hitting their head. They are running over a gap and then jumping on top of three enemies. They are running, then pausing to wait for the guard to pass, and then running again.

Complex Base Mechanics are when multiple Atomic Mechanics are tied together to create something new. These new actions are usually only taught to the player after they have mastered the underlying Atomic Mechanics. The game may teach them, or given enough time, they may find them themselves.

For out Bejeweled example, we said that the Atomic Base Mechanic is the player being able to click on two jewels and swap their locations. This allows the player to connect 3 and . But what happens when the player connects more than three? The jewels click down into place perfectly and…bam! They’ve created a chain; extra high points! By performing their Atomic Base Mechanics in a specific way, they complete the Complex Base Mechanic of making a chain.

In Chess, a gambit is where a player intentionally sacrifices a piece in order to gain a long term advantage. For example, they may put a pawn into a vulnerable position, because when the opponent takes that pawn, the opponent will be in an even more vulnerable position. There isn’t anything in the Atomic Mechanics of chess that discuss this concept, yet all experienced chess players can tell you what a gambit is. It is a Complex Base Mechanic, a result of combining several Atomic Mechanics into something more interesting.

How much support the developer gives Complex Mechanics (or any mechanic for that matter) is up to them. For example, in an action game, the player might be able to run and jump, and so of course the player might be able to run and jump simultaneously to reach new heights. The developer may simply allow the player to do this using the already existing Atomic Mechanics, or they may add a little extra “umph” to it, allowing the run+jump combination to cause the

player to jump unrealistically higher, with new special effects and sounds associated with it. How the developer crafts this and other Complex Base Mechanics is up to them.

The Big Picture

Base Mechanics are the building blocks of a game, but they are also heavily dependent on the other aspects of the Game Design Canvas. While they do make up the actions that the player is taking and constitute nearly 100% of the player’s playtie, a game made up of only Base Mechanics would be a boring game indeed.

A game’s Punishment and Reward Systems give meaning to the player’s actions; how does the player know what to do and when? In what way are these Mechanics supposed to be used and optimized? The Long Term Incentives provide the drive for the player to continue using these Base Mechanics over and over with continuing excitement and anticipation. And the Aesthetic Layout gives that pop to the player’s actions: a nice big “Combo!” when the player performs a correct sequence of actions. All of these aspects work together with the Base Mechanics, the player’s actions, to give them meaning and help deliver the Core Experience.

The Journey of a Thousand Miles…

“The journey of a thousand miles begins with a single step,” says the ancient proverb. In the same way, games are built step by step, Base Mechanic by Base Mechanic. Always supporting the Core Experience, Base Mechanics provide the building blocks of every game, guiding the player’s each moment. And if those bricks are well put together, it can be an incredible collection of moments indeed.

篇目2,Who cares if the main character is wearing silver armor or an orange cloak? Does it really matter if your military troop is fighting in Europe or Asia? There can’t be any difference between a game about saving the world, and one your one true love, right?

It does matter. In fact it matters a great deal. The sights and sounds and feeling contribute to the Core Experience of a game like no other part of the game can. They are what make games a true art form instead of pure science, they are what make games closer to theater than arithmetic, painting than to geometry. These artistic strokes are the skin that the world will see view the game, its face, its exterior.

Welcome to the fifth and final component of the Game Design Canvas: the Aesthetic Layout.

The Bells and Whistles

Hardcore gamers, and even some game developers, often tend to think of games exclusively as mechanical systems. This is expected, because these types of people have typically played so many games that they’ve become experts. Trained to analyze and dissect, they see through the smoke and boil the game down from bells and whistles to gears and oil. All of the other systems we’ve talked about within the Game Design Canvas, the Base Mechanics, the Punishment and Reward Systems, and the Long Term Incentive, are all of these gears. And once they see under the hood, they manipulate the gears as much as possible to get what they want.

This process is called “min-maxing” by game developers. Min-maxing is exerting the minimal amount of effort to get the maximum benefit in a game. Gamers and game developers are experts at this; they quickly understand the game and then find and implement the optimal path to win. It’s an old-school mentality that dates back to coin-op games, when the Core Experience of a game was to master the challenge and get the highest score. There’s nothing wrong with min-

maxing, or viewing game design as systems that create interesting min-maxing situations.

However, there are some aspects of games that are more than mechanics and systems. This final component of the Canvas is what gives the finesse, the real style, the elegance to a game. What the characters look like, how they sound when the jump or run, the backdrop in oil painting or in gritty photorealism. The pixel art of the items, or the solemn music as the player approaches the temple. The cutscenes and movie sequences, the story and plotline, the cover of

the game’s box. Well executed Aesthetics are extra bang that gets a great title noticed and remembered. Poor executed Aesthetics are the downfall of otherwise incredible experiences.

A game’s Aesthetic Layout is made up of several key subsections. The first three subsections are found in almost all traditional video games: Visual Design, Audio Design, and Content. The fourth subsection also appears in all games, but most traditional console and PC titles don’t think too much about it: Interaction Design.

Visual Design

The Visual Design of a game is easy to understand and difficult to master. It is how the game looks: the graphics, the sights, the colors, and pixels on the screen or on the cards in the player’s hand. Since humans rely on sight more than any other sense, the visual design of a game is vitally important. It is the most prominent aspect of the game that will appear on posters, advertisements, and the back of the retail box. The details of the captain’s face and wind-blown hair, the sparkles on the water, or the shine of a solar flare, these are the parts of a game’s visual design. Little extras that don’t affect the gameplay at all, such as airplanes flying overhead in Call of Duty, add to the player’s gameplay in an important yet indirect way.

Nowadays, this aspect of games is much more open ended than in the past, fueled by advances in technology as well as pioneering art directors through the past three decades. During the 90’s, the age of Super Nintendo and the first laystation, developers sought after the holy grail of perfect realism in games: the goal was to make a game that would be indistinguishable from real life. In the most recent decade, since that goal is nearly achieved on the Xbox 360 and Playstation 3, developers have been able to branch out a bit more and flex their own style.

Online web games such as Farmville often specialize in high-resolution cartoony images that feel comfortable and easy to understand. Independent games like Spelunky stick to modified versions of 90’s pixel art in order to give the experience of childhood nostalgia for those who grew up on Nintendo. Artistic titles such as Okami or Legend of Zelda: Wind Waker focus on highly stylized effects to give the player a sense of wonder. All of these Visual Designs support the Core Experience of their corresponding games, and maintain a high quality bar for other developers to match or exceed.

The Visual Design of a game says a lot about who will be playing it and what they will expect. Web games are easy to understand and have simple rules, but they won’t interest someone who is seeking a game of gritty realism like Gears of War. Thus, it would be a waste of effort to make its art style photorealistic; it’s important to know who will be playing a game when deciding on its Visual Design. The level of quality of this subsection is important to many players and obvious from the first glance. Even if the rest of the game is quite solid, players will be reluctant to try out a game if it doesn’t pass their minimum standard of visual design quality. Visual design is the fastest way that games become dated.

Audio Design

The sounds and music of a game are important. Taking cues from the film industry, games quickly learned that music could be used to great effect to evoke emotion and immersion in a game. A soundtrack to the valiant hero galloping towards apparent doom is certainly better experienced with epic strings and trumpets. A more playful game may use a bippity-boppity child-like music, such as Wii Play: Tanks, bringing the player back to their youth. Other games such

as Resident Evil choose to have dynamic music tracks, changing depending on the action on screen. Nervous, low music when roaming the dark streets, and frenzied, fast music when monsters burst through the walls. All of these choices support the Core Experience through the Aesthetic Layout’s Audio Design.

In addition to background music, a game’s audio sound effects play a great role on conveying the world. Again, in Wii Play: Tanks, Nintendo could have made the tiny tanks sound like the hulking juggernauts of first person shooters. But instead they gave them sound effects akin to wind-up toys. This seemingly insignificant touch focuses the target audience of the game, taking it away from people who want to drive a real tank and towards those who want to relive their long gone action figures and plastic vehicles.

Games that are meant to be played over long periods of time probably don’t want to have background music, while games that are meant to be told through story often use background music and sounds to great effect. Additionally, both Visual and Audio Design can aid the other parts of the Game Design Canvas by signifying when events occur, such as a red screen and beeping heart upon receiving damage. These are the choices that developers or audio artists need to

make.

Content

The Content of the game is the actual characters, the story, the setting and level design. On the development side, the content is usually thought of as the parts of the game actually input into the code not by engineers, but by designers and producers. A game’s plot line, whether it is about the overthrow of the evil Ganondorf or the pursuit of a long lost treasure, is part of the Aesthetic Layout’s Content. This Content sometimes don’t affect the game’s Mechanical systems in any way, yet like other aspects of the Aesthetic Layout, help to narrow who is interested in a game title and who is not. An RPG that is set in medieval times would not appeal to those who may actually play the same game were it set in modern day high school.

The story and character components of game can be inserted into the game however the developer likes. A game is built on top of rules and actions that the player performs (The Base Mechanics and P&R Systems), but from there they make their way through the game’s content. Each level provides new content; a situation that the player hasn’t seen before. Exactly how important the game’s story, characters, and plot are is up the developer. Some players like to min-max and skip through all of the story. Or the developer may choose to simply partition the plot to optional text such as in Braid. Exactly how important the Content is to the player is decided upon by the team.

Interaction Design

The final subsection of the Aesthetic Layout is Interaction Design, which are the methods and technologies that the player actually interacts with the game. Whether through button, motion, analog stick, a tennis racquet, or some other device that has yet to be invented, how the player actually interacts with the game is arguably the most important aspect not just of the Aesthetic Layout, but of the entire Game Design Canvas.

Most video games are played with a handheld controller on a television, but the Canvas includes all games, not just video games. The actual instruments and devices that the player uses to interact with the game are part of the game’s Aesthetic Layout. Exactly what these devices do is up to the Base Mechanics, and exactly what the consequences of those actions are is up to the Punishment and Reward Systems, but the actual devices themselves is decided here.

As we’ve already said, the classic gaming controller, with two joysticks, a directional pad, and buttons, is only one form of Interaction Design for games. Nintendo’s Wii remote is an example of a different one, where the player is required to point the remote at the television or wave it around. Further still from traditional video games is the sport of soccer, where the player is actually kicking a ball and making contact on a field. Another example is Poker, where the player deals and receives cards and has specific hand gestures that correspond to actions such as a call or fold. These are all situations where the Interaction Design affects the player’s experience of interacting with the game as well as other players.

Each of these devices and systems give the game a different Aesthetic feel. It’s up to the developer to decide what kind of Interaction Design they want their game to have, and how that choice enhances or detracts from the game’s Core xperience. It’s not enough to use a device just because it seems “fun” in a vacuum, for example, asking the player to turn the Wii remote every time the player needs to open a door. The developer needs to think and realize what that Aesthetic choice is actually doing to the player’s experience.

Importance of Aesthetic Layout to Players

The Aesthetic Layout is the most important component of the Game Design Canvas in terms of getting players to just try your game out. People with extensive experience in game development, especially design and engineering, tend to ignore the importance of graphics and sound in a game. But they ignore the importance of the Aesthetic Layout at their own risk. Many independent developers, for example, pour their heart and soul into creating games with incredibly

complex and innovative Base Mechanics. However, they neglect to consider, research, or even think about the game’s graphics, music, or sound style. It’s an afterthought, an area not deemed worthy of much innovation, and just copying everyone else is good enough. Unbeknownst to the developer, this ends up limiting the reception of the game to a small subset of the possible players who would truly find the game appealing.

If you’ll be willing to take a detour from games, one analogy that is applicable here can be found in the music recording industry. Country music, at least in the United States, has a bit of a stigma outside of the southern states. Many people frequently claim that they “Listen to all kinds of music…except country.” While the reasons for this are varied, the market split is very identifiable. If listeners hear a song that they believe is country, then they will automatically be turned off. However if it is of another genre that they’re more familiar with, they’ll be open to it.

Record labels and recording artists understand this. Having a song labeled as “country” has very real effects on the song’s mainstream potential. Thus, successful artists are very aware of the choices they’re making when producing a song. They will have decided beforehand what market they want the song to perform well in, and then accommodate in the track.

As a result, you’ll often hear subtle, seemingly meaningless differences in the mainstream and country versions of a popular song. It can be as simple as replacing a background instrument from a banjo (country) to an electric guitar (mainstream pop). This is the only change in the song, and yet this small change has severe implications. Listeners who hear the version with the banjo will, within seconds, deny the possibility that they might enjoy the song. They

are completely closed off to it. However hearing the same song with the electric guitar is treated like any other pop song, and they evaluate the song fairly like they would any other pop song.

So back to the games industry, it would be beneficial to developers to be aware of the limiting (or expanding) effects that aesthetic layout alone can have on a game’s reception. It’s a tragedy to see a game with unique Gameplay not even be considered by players because the Aesthetic Layout was goofed. For example, a game that would appeal to older women, but has the graphics of a 90’s medieval RPG.

Painting Worlds and Inviting Players

The Aesthetic Layout is incredibly important for developers to think about, because it determines a game’s audience. The images and sound, story and input devices, though seemingly divorced from the rest of the game’s design, greatly affect who will be open minded about a game and who will never give it a chance. Additionally, it is the artist’s chance to leave their mark on a game, to take something that is just a simple computer program and liken it to a masterpiece painting. By nurturing these elements to their fullest, game developers can begin to construct and complete their works of art for the world to interact with.