万字长文,关于游戏趣味性起源和构成的相关探讨,补录

篇目1,游戏乐趣元素的构成解析

作者:Sandra Wong

在Lucky Lady游戏工作室,关于游戏设计,我们认为最重要的问题是“有趣吗?”。你的游戏中可能有最精美的画面、最动人的音乐、最强大的技术、最深刻的情节等,但没有任何有趣的元素,这样的游戏并没有成功地发挥它的全部潜能(如果有的话)。

乐趣是玩家留存率、流行/推广价值和赢利的基础,所以如果你想制作一款成功的社交游戏,你必须首先专注于乐趣,其他一切都不能比乐趣来得重要。事实上,乐趣实在太重要了,以致于玩家甚至可以无视其他并不太突出的方面仍然继续玩某一款游戏。

have-lots-of-fun(from minimalwall.com)

如何在游戏设计中实现乐趣?

乐趣因素绝对不能够轻易得到的东西,并且这个问题也没有标准答案。找到乐趣与游戏玩法的和谐点是所有游戏设计师的目标。为了达到目标,我们建议在游戏设计过程中尝试大量a/b测试。你觉得这款游戏有趣吗?为什么有趣或无趣?你还要补充什么?你希望看到什么?

那些从书面理论上“看似”有趣的东西,可能无法完美地转化到现实成果中。根据你所设计的游戏类型,“乐趣”元素具有不同的形式。游戏实现平衡的秘密就是,将所有“乐趣”元素放游戏中并不能保证游戏变得更加“有趣”,但适合游戏玩法。

“游戏乐趣”的心理学与“游戏成瘾”的非常类似。

以下是游戏设计中普遍的“乐趣”元素/陷阱:

击败最高分

击败最高分是最容易识别的手段之一。玩家击败最高分(即使最高分就是他自己创下的)的渴望会支持着玩家一直玩下去。

击败游戏/升级

击败游戏的渴望或升级也能保持游戏对玩家的吸引力。

角色扮演

游戏情节使玩家暂时逃避现实生活,也是吸引玩家的上乘手段。

发现

在RPG中最常见的元素,如《WOW》,玩家在游戏中的很多时间都用在探索这个幻想世界。这种发现的兴奋感(即使那个地方其实并不存在)对玩家有相当大的吸引力。

关系

在线RPG使玩家之间建立起某种关系。对于某些玩家而言,这个在线社区成为他们最认可的地方,吸引着他们一次又一次地回归游戏。

元游戏

有时候,真正的游戏玩法可能并不是游戏中的乐趣元素。例如,《Farmville》的元游戏就是社交活动。“邀请朋友”和赠送道具,可能比游戏本身的农场玩法更有趣。

动作

移除障碍、躲避飞弹、旋转……所有游戏都需要某些类型的玩家互动。

随机

收集道具、点数、积分榜……人类喜欢收集东西,因为这使他们觉得自己达到了目标,从而产生某种成就感。

控制

玩家选项、解锁场景、进入新关卡……使玩家感觉到自己在游戏中的地位和对游戏世界的影响力。

自定义

角色外貌、服装、武器……角色的个性化使玩家觉得自己掌控着游戏世界,进而产生归属感和对游戏的忠诚。

平衡

游戏挑战和流程。游戏的进展必须合理:例如,如果你没有通过第3关就不能进入第5关。

幽默

笑总是有趣的,在游戏中添加幽默元素可以使玩家开心。毕竟,现实世界太严肃了……

最后,希望你在设计游戏时努力增加“乐趣”元素!

篇目2,“失败是一种乐趣”的游戏设计可行吗

作者:Josh Bycer

如果你玩过像《幽浮》,《洞穴探险》和《矮人要塞》等困难的电子游戏,你便可能听过有人用“失败是一种乐趣”去描述它们。失败是一种乐趣意味着游戏设计的目的是为了被战胜且攻克挑战。

就我个人来说,我讨厌人们将其作为游戏设计的辩词,即它通常都是任何有关难度和设计的讨论的说辞。失败作为乐趣是可行的,但在我看来如果它作为一种可接受的设计将不具有多大的优势。

.jpg)

Dark Souls(from game-wisdom)

平衡进程:

为了谈论游戏难度,我们首先需要简单地说下游戏设计中的两种进程。玩家进程是指玩家在游戏中完善他们的知识和技能。而角色进程则是关于游戏中任何影响玩家成功机会的元素:升级,道具等等。

这意味着当提到失败时,这两种进程形式将具有不同的感受。在基于技能的游戏中,失败意味着作为玩家的你并未达到胜利所要求的技能水平,而问题是出在你身上。而在基于角色的游戏中失败则意味着安静控制之外的情况是其失败的原因。也许他们并未在战斗中购买足够强大的武器或获得随机数量的生成器而给敌人致命一击。

当提到游戏失败是否让人沮丧以及哪里的失败是有趣的时,玩家对于成功的控制数量是很难进行调整的。

适当的惩罚:

当提到游戏设计时,重玩价值是个很重要的理念,并且是难度游戏或者那些玩家必须立刻重新开始的游戏内容的主要组件。如果你的游戏是关于每次失败都从0开始,那么游戏便非常需要重玩价值。

在我看来,为了保证失败是一种乐趣是正确的,游戏的进程就必须是进程的极端。

在基于像《洞穴探险》这样的技能游戏或那些带有少许RPG元素的游戏,如《恶魔灵魂》,玩家便是决定输赢的关键元素。

在像《洞穴探险》这样的游戏中遭遇失败并没关系,因为它总是会带给你一些经验教训,让你能够在下一次尝试中利用起来。

关于角色进程或强大的随机元素,像在《以撒的结合》或《地下城冒险》中,游戏设计总是具有许多可变性,从而导致你对于自己的输赢缺少足够的控制,所以如果你遭遇了失败也不全是自己的错。也许敌人碰巧击中了你,或者你找不到任何强大的升级工具去获取胜利。

不管是哪种情况,失败要么是受到玩家行动的控制,要么是完全脱离玩家的控制。所以在我看来,将失败当成一种乐趣意味着玩家需要变得更好,或者只是想再次滚动骰子看看会发生些什么。

从根本上看来,为了让“失败是一种乐趣”发挥作用,游戏中就必须包含一个主要的重玩价值细节内容:玩家必须能在每次游戏时获得某种形式的成长。

游戏绝对要避免掉进一种常规,即未提供给玩家任何可继续学习的内容。

发展可以是一种基于技能的IE:玩家通过反复尝试去摸索打败boss的正确方法。或者是基于角色:在尝试了许多不同的技能组合后,玩家找到一种自己喜欢的。如果游戏变成一种纯粹的刷任务,那么“失败是一种乐趣”便不再可行。

我写下这篇文章的主要原因是来自《幽浮:未知的敌人》(游戏邦注:以及最近的扩展《内部敌人》)。

我听过人们因为选择和角色而在提及《未知的敌人》时表明了失败是一种乐趣的观点,就像这全部是关于打着一场艰难的战斗。关于《未知的敌人》,我所遇到的问题是到达了一个临界点,即坚持对抗一个经典的钢铁人,那时候游戏的角色平衡和基于技能的进程开始停滞不前了。

因为游戏的覆盖系统以及敌人破坏的随机性,游戏的战术面或者技能获得奖励之处对于我来说都太过于随机,以至于很难再学到什么。

关于策略方面或角色进程—-即我知道自己需要做些什么,但却不能在战术部分依赖于技能,在整个活动中对于进程起着巨大的影响作用。

就像我在关于《内部敌人》的分析中提到的,游戏的反馈循环是非常两极化的,如果你开始在某些地方落后了,你便很难恢复了。基于基地创建和研究进程,我知道正确的创建顺序去战胜经典的内容。但如果我不能快速推动角色的发展,或打开正确的研究内容,我便不可能在过去的两个月中生存下来。

所以我的游戏可能会在两个月结束后终止,或者我会继续坚持玩几个月然后基于自己的策略和运气获取胜利或遭遇失败。

举个例子来说吧,就像我便很多次因为游戏的随机性而不能拯救角色并失去整个群组。

如果你的游戏是关于技能推动进程,那就需要确保玩家的技能足以影响游戏玩法。另一方面,如果你的游戏是关于角色进程和随机性,那么游戏就必须是随机的,即不存在任一种每次都能取胜的方法。

我并不喜欢听到“失败是一种乐趣”这种说法,这通常是在包庇游戏设计问题免受批评。

如果玩游戏是一种受挫的体验,那么我便不会去关心失败会有多少乐趣。

这也是为何那些围绕着不断失败而实现平衡的游戏有可能是最佳设计游戏也有可能是最糟糕的游戏。

平衡必须确保玩家能够沉浸于通过自己的努力获得进程的游戏中。

篇目3,好游戏应为玩家提供一系列有趣的选择

作者:Stephen Totilo

在我玩电子游戏的头25年中,我并不知道制作出色的电子游戏需要遵从哪些理论。我只感觉得到哪些是好游戏。

去年我被迫为此总结一个理论——制作出色电子游戏的理论。我的理论很简单,无论是射击、开飞机、跳过蘑菇、解决谜题还是翻转降落方块,游戏对玩家来说就是一系列的选择。优秀电子游戏会为玩家呈现一系列有趣的选择。如果游戏的选择很无趣,或者它们根本就不能算是选择,那么这款游戏就很糟糕。

2011年的一些事件让我不得不开始为制作好游戏而提炼一些理论。这些事件与Zynga有关,当时我听说Zynga游戏不过是利用一些心理伎俩诱使玩家持续玩游戏,而非通过娱乐玩家鼓励其体验游戏。我听说有成百上千万玩家拥护Zynga游戏,但这些玩家并不知道这些游戏对自己有什么好处。有评论直言,Zynga所做的东西非但不能称为坏游戏,甚至连游戏都算不上。

而令人尴尬的是,Zynga在整个2011年基本上每月都邀请我去体验他们的游戏,因为我在一家主流电子游戏网站任职,他们希望我能为其游戏发表积极的报道和评价。我当时并不想玩他们的游戏,但作为新闻记者我又不能将信息拒之门外,所以我每月都回复他们,我会试试你们的游戏。

在此之前,我仅玩过几分钟的《FarmVille》,这款游戏一开始时并没有呈现什么让我感兴趣的选择。它只是将我推向一步接一步的操作,告诉我要建设什么,搜集什么,等待什么,我在其中完全没有自主做决定的感觉。这款游戏让我觉得无聊。

后来Zynga又向我展示了《FrontierVille》,他们向我讲述了游戏的故事。但这也并没有让我心生向往。他们又跟我推荐了《Empires & Allies》(借鉴了《Advance Wars》的一些灵感),我从其中的战斗系统中意识到,玩家可能会输掉战斗。输掉的玩家必须有一个走向胜利或失败的选择,我对这款游戏较有兴趣,但试过之后很快就厌烦了。

后来我又试玩了《Adventure World》(游戏邦注:Zynga后来将该游戏更名为《Indiana Jones Aventure》,游戏中的主角很讨厌蛇,其中的一场与蛇相遇的情况则让我相信,《Adventure World》不但算得上游戏,而且还有成为好游戏的潜力。

我将通过以下截图重现我初试游戏所遇到的情况:

Adventure World 1(from kotaku)

首先,我进入游戏中的一个地图并发现我可以选择自己要去的一个地方。在画面左上方有一条路,可以将我引到一个灌木丛,但我需要斩荆披棘地破开这条路。我不知道其中可能隐藏了什么东西。而右边的这条路则将把我引向一个红色的宝物,但旁边有一条蛇在虎视眈眈,随时可能向我扑来。

Adventure World 2(from kotaku)

我选择走向宝物所在之处,也就是说走向那条蛇。

Adventure World 3(from kotaku)

我拿到了宝物,蛇也向我靠近。

Adventure World 4(from kotaku)

我决定与蛇拼命而非逃之夭夭,我发现这条蛇很容易解决,就将它杀死了。

这在电子游戏史上不算什么最具吸引力的选择,但它们毕竟还是选择。它们是可以直接引向明显结果的选择,这引起了我的兴趣。

而当Zynga成员又让我去玩《Mafia Wars 2》时,我就知道自己要找的是什么了——选择。我认为,游戏中的选择越多越好,至少对Zynga来说是这样。我认为Zynga成员越来越进步了。他们不再制作一些没有分支的流程图表让用户点击,他们也开始懂得为玩家提供分支,他们提供了一些拥有明显结果的选择。

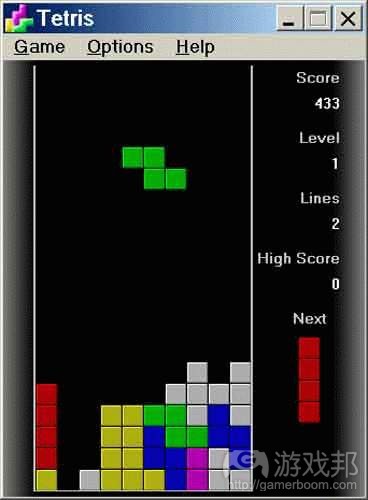

《俄罗斯方块》为何能成为经典?

tetris(from takegame.com)

我认为电子游戏必须存在选择的这个想法成形后,我开始从自己最喜欢的电子游戏中寻找不同之处。我喜欢《Metroids》和《刺客信条》,这两者无疑都是算是电子游戏。虽然《赛尔达传说:梅祖拉的面具》是我最喜欢的电子游戏,但我认为史上最出色的电子游戏当属《俄罗斯方块》。我所列出的这些游戏都能够支持我这个理论,而《俄罗斯方块》在这一点上的表现更为明显,这也是它为何是最佳游戏的原因。游戏中的每个下坠的方块都呈现了一些有趣的选择:我该向哪放置这个方块?我是否能快速翻转它?还是该让它迅速到位?下一个方块是什么,我当前放置的方块对它有什么影响……这些选择很快呈现并且很明确。其结果有时候是立即呈现,有时候会延迟出现。但它们都很明显。

这款游戏并只是一些下坠的方块,而是一连串做出决定的机会。

Merihari和叉子

我征求了自己所知的一些杰出电子游戏开发者的看法,询问他们判断好坏游戏的标准。我的理论是好游戏会呈现有趣的选择,那么他们的理论又是什么呢?

身在日本的Dylan Cuthbert(游戏邦注:他曾参与开发《Star Fox》、《PixelJunk Monsters》和《Digidrive》等游戏,并与曾与任天堂京都总部的一些高层合作)通过电子邮件表示,“这是一个见仁见智的问题。例如,我认为《暗黑之魂》是杰出的游戏,但其他人可能另有看法。不过,真正的好游戏总有一些共同特点。对我来说,这些特点包括美感(不局限于美术设计),优化、粘性、原创性和‘Merihari’”。

“你可能会问什么是’Merihari’,它是一个日本词,包含节奏+平衡+分配——例如,坐过山车的时候如果缺了Merihari,那就只是在进行持续的下坡。这听起来可能不错,但如果没有最初攀升时的那种紧张感,这种体验就会丧失大量的刺激性。这也是为何游戏中的boss战斗能够发挥作用的原因。在遭遇boss之前要先塑造一种紧张感。如果你的游戏只有boss战斗,这种体验就会很肤浅”。(这让我想起了出自Polyphony之手的《Omega Boost》,如果它在boss战斗前营造了足够的紧张感,可能会是一款更好的游戏)

“最主要的因素,我想就是热爱与在乎——如果整个开发团队都热爱并且在乎这款游戏,只要具备这一点就可以制作出很棒的游戏。”

Merihari这个理念听起来不错。那么我要改一下这个理论:有趣的决策+Merihari。但也许还可以再添加其他元素。

身在纽约的游戏设计师兼学者Eric Zimmerman的回答是:

“我认为这个问题的答案无法简单概括,比如我们不能说哪种特定的游戏设计或特定的玩家体验就是好的。我认为构成出色的玩家体验的元素是设计本身的问题之一。游戏设计师需自己决定游戏成功的方向,并据此设计游戏。”

“比起其他领域的设计师(例如建筑师或工业设计师),让设计师定义自己的设计问题对游戏设计师而言尤为重要,因为我们的工作没有那么明显的功利性。叉子设计师通常要以叉子的用途来定义其设计的成功:叉子是让人用来吃东西的”。

“但在游戏设计中,我们得自己制定成功的标准。这可能包括美学目标,探索或传送思想的目标,商业标准以及技术创新性等。当然,所有的这些目标都是非游戏设计师也需要考虑的东西。例如,叉子设计师也会有自己的美学目标。但对非教育类游戏来说,这些非功用性目标就是我们的追求。”

“所以游戏好坏应由游戏设计师自主决定。而各个设计师又有不同的判断标准,一款游戏之所以优秀可能是因为它触动你的悲伤、快乐或愤怒的情感。因为它让玩家放松或者兴奋,或者将他们引入一个禅宗境界,或者让他们提高解决问题的灵敏性。游戏设计师可以决定游戏的成功是来自友爱的社交互动,不知所云的聊天,还是孤立感。这种成功也可能与新型暴力元素有关,或者是对小提琴的新诠释。通常情况下,这是许多不同甚至有时相互矛盾的元素所融合的成功标准。”

这让我想起了我自己最初的困惑——这个困惑并非如何区分游戏的好坏,而是如何定义某些事物(尤其是Zynga公司的产品)究竟算不算游戏。Zimmerman并没有特别解释这一点,但他的评论却让我幡然醒悟,我终于知道为什么玩Zynga游戏难以让我放松——我在这些游戏中每做一个决定,游戏就会明显暴露出开发者希望用户付费的意图。我每做一个决定,都得使用一定的能量,都会让我更近一步走向不得不等待的时刻(这让人很烦),要不就得去骚扰好友以求获得帮助(这让我看起来像是在替Zynga推广游戏),或者付费购买更多能量。

这里可能得再修正一下我的理论:优秀的电子游戏不但要包含有趣的决策,而且这些决策不能让我感觉自己像是被操纵/利用/敲竹竿。

《超级马里奥》中的决策

在2012年,我带着自己的理论寻找那些充满选择的游戏。Zynga成员仍在向我推荐他们的游戏。如果这些游戏并不能提供我之前所体验到的那些选择——或者并没有提供具有直接结果的选择,我就会失去兴趣。

在这一过程中,我发现自己偏爱第一人称射击游戏,但对那些具有线性特点,并不提供解决问题的选择的游戏没有多大兴趣(这也是为何我特喜欢2011年的《子弹风暴》的原因,游戏中的每场敌人遭遇战都提供了大量获胜的选择)。

我意识到自己比较难以接受日本角色扮演游戏,可能就是因为它们所呈现的故事缺乏选择(这也是为何我喜欢《Fire Emblems》,并且排斥刷任务机制的原因)。

我喜欢《愤怒的小鸟太空版》,但对选择有限的《Ace Attorney》不感兴趣也正是因为,我追求的是具有交互性的决策制定元素。

我现在很乐衷于在游戏中做截然不同的选择,然后看看游戏会出现什么结果。如果我觉得自己像是被迫去做特定的事情,我就会很抵触,很气恼。我会讨厌这种游戏。这也正是为何我去年爱玩《传送门2》的原因,它的每个谜题可能只有一个解决方法,但却可以让我觉得自己是在制定决策。而这也能够解释为何我不喜欢《神秘海域3》,因为它只会针对相同的敌人提供同样的选择。

我寻找含有大量选择的游戏,并不意味着我只找BioWare风格,含有大量分支路径的角色扮演游戏。对我而言,一个选择可以含有两个不同的目标。它可以简单到决定是否要跳跃。

超级马里奥(from kotaku)

我一直深为《超级马里奥》中的跳跃动作而着迷,我认为它是电子游戏中最完美的动作,马里奥向上攀升的过程中会伴随着探索发现。向上过程中他可能会撞到将生出蘑菇或花朵的砖块。而他的下坠而是一种进攻动作,他可以踩扁敌人。将这一上一下动作结合起来,则可以跨越无底洞或躲过食肉植物。游戏关卡每一处都在为玩家呈现一连串选择,这些选择几乎都在促使玩家决定是否或如何向上跳跃,向下踩踏。

马里奥系列中的最佳关卡是由一系列障碍组成,如果玩家快速接近这些障碍,就刽同到一些令人快乐的困境。我应该跑步跳过这个人吗?但遇到下个人我该怎么办?我应该跳上这只龟并用它的壳打下一敌人,还是挨个跳过它们的脑袋?

也许呈现有趣的选择是判断好游戏的标准,这是一个极为显而易见的理论。也许这一理论并不能区分游戏优秀与出色之处。但对于我这样的游戏玩家来说,它确实让我更清楚地意识到游戏如何占用了我的时间。如果它为每分每秒都为我提供有趣的选择,我可能就会喜欢它。如果没有,我最好就不要玩这种游戏。这就是我区分好坏游戏的标准。

篇目4,游戏设计哲学——趣味性地位超越艺术性

作者:David Ethan Kennerly

这篇文章所述绝不是游戏设计的哲学理论,但是这些观点可能会对有抱负的游戏设计师在开始工作之前、检查工作以及目标合理程度时有所帮助。

不要误认为自己是‘艺术师’。我们的目标是创造出更新和更有趣的游戏。艺术性不是我们的目标。——《最终幻想》角色设计师Tetsuya Nomura

趣味性和艺术性之间的讨论不绝于耳。这些参与者可能会从中得到乐趣,但是这两者的对立却不适合出现在游戏中。比如在MMORPG中,对Jessica Mulligan而言,趣味性包含艺术性,而对Raph Koster而言是艺术性包含趣味性。我将挑战这种对立观点。构建趣味性本身就是游戏的艺术。

Stephen King说过:把你的游戏设计桌放在角落里,每天提醒自己艺术支撑着生活,没有其他的方法了。在这篇文章的末尾,或许我们可以解开这种错误的对立谜团。重新考虑游戏、趣味和艺术层面之后,我们或许会发现Nomura和Costikyan的说法是正确的。

如果你想要编写21世纪的《Seven Lively Arts》的话,你首先会想到的形式显然是游戏。——Greg Costikyan

在开始解析之时,我们需要先将游戏视为独特的媒介。

独特的媒介

游戏与其他形式的艺术不同。如果要给游戏下个定义的话,存在一定目的,有玩家和规则,即可算是游戏。当然,游戏也可能是服务、世界或社区的一部分。为使得游戏不与所有运用了游戏理论的领域(游戏邦注:如经济、心理学、政治和实验分析)相混淆,我使用了“室内游戏”这个术语。

指环王:双塔奇兵(from xbox.ign.com)

视频游戏《指环王:双塔奇兵》的音效设计师写道:“将游戏视为‘互动电影’是不恰当的,尽管有许多人这么做。很显然,游戏和电影是不同的媒体。这两种媒体创造所涉及的技术、过程和技能都各不相同而且不可互换。判断的度量也不同,这意味着许多能够成就优秀电影的属性可能铸造出劣质的游戏,反之亦然。”

多数电影和游戏的叙事也有着显著的差别,因为游戏中的故事并不来源于游戏本身,而是来源于玩家。叙事是种被动体验,人们看到事件而且心有所感,但是却无法做出行动,因为观众并非演员。而在游戏中,观众就是演员。这里存在目标冲突。叙事的作者必须控制演员的生活,而游戏设计师必须杜绝对玩家的控制。这也就解释了Will Wright向初出茅庐的游戏设计师提的首个意见:游戏是要让玩家感受到乐趣,而不是作者解决他们想要解决的叙事问题的平台。

部分问题在于,知识产权领域很少将优秀的故事和优秀的游戏联系起来。《龙与地下城》并非J.R.R. Tolkien的游戏媒介。《American McGee’s Alice》也并非Lewis Carroll的游戏媒介改编版本、。Reiner Knizia的合作桌游《指环王》即将面世,这款游戏保留了小说的精髓。但是,《指环王》看起来仍然更像是小说而不是优秀的游戏。

诸如《银河飞将》和《马里奥兄弟》等许多游戏向电影的转型都失败了,电影到游戏的转型也是如此,比如Atari的《E.T.》或《勇敢的心》。这些失败给我们的教训是:电影只能迎合观众,游戏只能满足玩家。如果想在游戏中寻找电影体验很艰难,反之亦然。尽管优秀的游戏能够让某些玩家产生很强烈的感觉,但是不可在游戏中追寻J.R.R. Tolkien或Lewis Carroll的身影。同样,我们在故事中也看不到Reiner Knizia、Sid Sackson或Harold S. Vanderbilt。

游戏设计师可以从其他媒介中借鉴灵感,但是无法借鉴技术或价值。比如,受电影中节奏启发与研究电影中的节奏并将其用在游戏中有很大的差别。如果我成功地借鉴了其他艺术形式,也只是灵感而已。如果没有理解这一点,可能会产生如下场景:

游戏开发变成马戏团,成本飞涨,用户很快就感到厌倦,对真正新游戏以及获得趣味的新方法的开发完全停止。——原任天堂总裁Yamauchi

优秀的游戏不会类似于其他媒介的优秀艺术。举个极端的例子:类似于《ChuChu Rocket》的电影有多好呢?这种做法会降低其他艺术形式的质量。它缺乏故事、深度以及抓人眼球的东西。

然而,它仍然是个优秀的游戏。游戏可以带来活跃并让人感到快乐的体验,正是玩家的存在让这种体验产生。

理解这些趣味性的类别能够扩展优秀游戏的范围。正如我们看到的那样,游戏设计师应当优先考虑趣味性。

从审视趣味性的角度来看从审视趣味性的角度来看,所有的艺术形式都是游戏设计师的艺术。——Oscar Wilde

当讨论起游戏设计的艺术性时,趣味性便是衡量的尺度,而不是现实性、新奇性、叙事性、哲学性、令人印象深刻的技术和视觉质量。

先让我们给这个术语下个定义。和许多普通的词汇一样,趣味性承载着各种各样的含义。在韩国,趣味性描述的是获得乐趣、娱乐并产生兴趣。美国人有时也会将某些此类词语结合起来。但是我的看法与传统观念不同。我觉得像在电影中在屏幕上看到爆炸并不有趣,但是在屏幕上创造出爆炸很有趣,就像在游戏中那样。我的意思是能够主动控制的趣味性,正如Patricia Marks Greenfield所述:“他们一致同意更喜欢游戏而不是电视。理由也很一致:(游戏可以让他们掌握)主动控制权。”所以,现如今以及这篇文章中所说的趣味性,指的是你可以通过每次行为直接影响结果带来的快感。

我对趣味性的理解同Sid Meier、Will Wright、Tetsuyu Nomura和Yamauchi相同,即互动性体验。在绘画、歌曲、电影、书籍或电视剧中,观众无法在剧情过程中改变结果。在优秀的游戏中,玩家可以通过每次行动来改变结果。

许多游戏设计师有着广泛的兴趣点。尽管对现实性的考虑、虚拟其他内容、多主人公的故事剧情这些对系统构建者来说很有趣,但是游戏设计的艺术就是创造出玩家觉得有趣的东西。在20世纪90年代中期,Sid Meier就在许多的采访中提到了这一点。比如,在接受Richard Rouse III的采访时,他说道:“在我们的游戏设计规则中,我们将游戏分为三个类别。有些游戏是设计师享受乐趣,有些游戏是电脑享受乐趣,有些游戏是玩家享受乐趣。我想我们应当制作的是让玩家享受乐趣的游戏。”

向玩家出售游戏的职业游戏设计师应当追随Sid Meier的步伐,尝试去设计其所述的第三类游戏。各类行业从业人员都对此表示认同。故事顾问Brad Kane说道:“最后要强调的是,游戏必须有趣,再有深度情感也无法拯救乏味的游戏。”

网络世界设计师Starr Long说道:“趣味性总是凌驾于现实性之上,毕竟这样才能算是真正的游戏。”

独立开发者Perry Board说道:“不要忘记玩家感受到的趣味性。你的整体目标就是提供乐趣。你做的所有事情都应该以此目标为中心。”

纸笔设计师Monte Cook、Jonathan Tweet和Skip Williams说道:“趣味性是强大的驱动力量,千万不可忘记。”

桌游设计师Reiner Knizia说道:“游戏只是人们享受乐趣的平台而已。”

趣味性并不一定通过优秀的游戏来呈现,但是优秀的游戏必须具有趣味性。

提升学习能力

人性已经得到了提升,当它得到提升之时,并非因为其原先冷静、负责和谨慎,而是因为其原先更好玩、反叛和不成熟。——Tom Robbins

将趣味性排除在外并不好。我们可以看到,趣味性是种宝贵的天性。

游戏的历史甚至超过人类存在的历史。年幼的哺乳动物会玩耍,但是它们没有特定的规则,因而不能称之为游戏。但是与观看电影相比,哺乳动物玩耍的行为与人类游戏行为的共同点更多。玩家行为甚至还能够与智力的进化联系起来。达尔文早期对进化的描述就类似于游戏。我们通常都会认识到,我们玩耍的本性就是为了追求趣味感。

如果是这样的话,那么趣味性就不是简单的东西。它演变出更为复杂的战略。花1分钟学习,花1辈子掌握,这条古老的谚语在游戏中同样适用,因为策略刚开始很简单,但是会发展得越来越复杂。科学和艺术的吸引力也正源于这种本性。趣味性是创造性的根源。爱因斯坦之所以开始学习数学,是因为他的叔叔将数学当成游戏介绍给他。费曼之所以能够获得诺贝尔奖,正是因为他从科学研究中找寻到乐趣。

在优秀的游戏中,趣味性能够与优秀的艺术相融合。这里的优秀艺术指的是本质上绝妙的艺术:优秀艺术是艺术的终极成品,或者是最完美的艺术。古有说法:“研究的越深便越觉得亚里士多德聪明。”在优秀的游戏中,玩家研究得越深,游戏就变得越有深度。一旦玩家知道了游戏中的完美战略,比如一字棋游戏,那么无论再玩多少次也找不出更好的战略。当游戏不会再让玩家有所收获时,游戏就不再有趣。当玩家在玩游戏时,也是个学习和特殊系统的教育过程。当找到完美方法时,就没有可供学习的新东西了。但是,在《Lost Cities》和《Go》等优秀游戏中,每次重复游玩都可以得到新的经验。找到新策略,发现老策略的不足之处。这种惊奇能够引导发现,也能够刺激科学和艺术向前发展。

因而,趣味性是游戏的艺术,这是个崇高的目标。优秀游戏能够让畅玩其中的玩家的心智能力呈螺旋上升。甚至连选择游玩战略的战略都得到了进步。游戏范围内的目标得以改变,使得人们学到某些东西。

人类境况

Paul Schwanz正在寻找某些比他在有些游戏中的体验更好的东西,他说道:“互动娱乐能够提供哪些堪比Steinbeck的《Of Mice and Men》、Coppola的《The Godfather》和莎士比亚的《哈姆雷特》的体验?”MMORPG创意总监Raph Koster持有相似的观点,他表示:“如果我们希望能够改革什么的话,那么为何不改变普通动画比游戏更能展示人类境况这个事实呢?”

优秀的游戏确实能够勾画出人类境况。有三个例子:《Spades》,7张扑克和象棋。

1、正如Steinbeck的经典之作《Of Mice and Men》,《Spades》是两个低阶级工人在美国经济大萧条时期左右发明的两人游戏。这款游戏已经被工人阶层的人玩了数十年之久,这些玩家所处的境地与Steinbeck所描绘的角色类似。在游戏中,合作者打赌他们可以赢得多少分,很像大萧条时期的境况。因此,我不认为自己在军中的好友在闲暇时间玩《Spades》是种巧合。优秀的《Spades》玩家学到了很多后工业时代服务业工人的情况。他们了解了自我评价以及团队行动比个人有着更高的价值。

2、7张扑克是美国生意场上排名倒数第二的游戏。扑克可以教导人们进行统计化的考量。电影《Pirates of the Silicon Valley》中声称比尔·盖茨在大学期间是扑克高手,这预示着他可以在商业上获得成功。

3、《哈姆雷特》和象棋的立足点是相同的。在玩象棋的过程中,人们可以意识到许多有关封建及后封建政治的状况。人类的生活体现在自由的移动中。每个玩家都将通过不断地移动其他棋子来使得自己的国王能够自由移动。

音乐师Sting希望游戏能够反映人类的境况。《文明》、象棋、《Settlers of Catan》和《Diplomacy》之类的游戏中都包含屠杀、谋杀、崇尚力量、土地侵犯和经济危机等元素。

优秀的游戏能够反映出人类境况,如果你相信以下说法:世界就类似于游戏,我们所有人都是玩家。我们的移动都是受到限制的,由此产生的后果无法挽救。

篇目5,Bennett Foddy称痛苦元素可增添游戏趣味性

作者:Brandon Sheffield

《QWOP》、《GIRP》以及《CLOP》开发者Bennett Foddy喜欢同玩家一起体验游戏,他建议更多的开发者应采取同种方式。

他在周五的IndieCade大会上的重要谈话中宣称:“我打算说服你们在游戏中添加更多的痛苦元素。”

他表示自己从奥运会上获得的最大感触就是亚军获得者的痛苦。

qwop(from geekosystem.com)

他解释道:“当玩家在电子游戏中取得第二名的成绩时,他们并未因此而哭泣。没有哪位玩家倒头失声痛哭,这是为什么呢?”

他指出:“在田径类的电子游戏中,快速按下某个按钮,或者快速摆动摇杆,就可以控制玩家角色的跑步方式。但这种控制方法却没有任何乐趣,游戏中的趣味存在恐慌之中——即好友看到你因按下按钮而伤害到自己时感到的快乐。”

Foddy表示:“这不仅仅因为游戏玩法相对更加简单。在我看来,当前的游戏让玩家体会到更多的舒适感,游戏中较少存在不快因素。而我担心的不是游戏变得太过容易上手,因为简单的游戏也有可能很精彩。我担心的是游戏变得过于舒适。”

那么,游戏中存在痛苦元素有哪些优势呢?Foddy指出:“当你在游戏中受挫时,它会突显失败的份量。”比如,《反恐精英》中采取的厌烦元素。即如果你在游戏中失败,那么你就必须观看其他玩家继续游戏进程,然而,游戏中更多采用挫败感元素。

Foddy表示:“游戏中的痛苦元素同样可以提升成功的重要性。”如果你能到达终点,你就会越发体会到成功的快感。他指出:“因此,本次谈话如同针对游戏的一封情书,让你体验到地狱般的经历,因为我们享受这种痛苦的过程。”

“通常当我开始设计一款游戏时,我会考虑游戏输入方式的美感。”假使不存在游戏,这种互动性还会有趣吗?Foddy表示:“大多数体育运动都能以此方式进行”,无规则的接球游戏仍然趣味十足。

其中一个例子就是敲击键盘,它存在固有的满足感,而这也是《CLOP》游戏创作的灵感来源,该游戏使用H、J、K和L四个键。

Foddy表示:“我打算设计一款反人类工学的游戏,这对于体验该游戏的玩家而言是一种肢体挑战,你可能会告诉好友:‘我已经玩了3个小时了,我有必要上医院看下。’”

Foddy已经在游戏中研究过痛苦、困惑和憎恶感,目的是让玩家体会到这种感受。

《德军司令部3D》让人感到憎恨,但却未让你从中感觉良好。Foddy表示:“我并未对该游戏感觉良好,因为这并非游戏的重点。我认为你可以制作一款以憎恶感为主的游戏,人们会因此喜欢上它。”

作为赋予玩家羞辱感的一个例子,《格斗之王》提供的是一种命运的历程。“你可能认为游戏的目的是为了愉悦赢家,而我却不这样认为。即使处于输的一方,作为玩家的我仍能享受到其中的乐趣。”

作为开发者,他们开发游戏的最终目的是同玩家一道体验游戏。Foddy指出:“我之所以区分这些不同程度的痛苦,是因为为何沮丧让人感觉良好?为何困惑或羞辱是美好的?我想,原因之一就是它代表着开发者同玩家一同体验游戏进程。”

许多开发者认为游戏中存在困惑是设计上的一个败笔。这意味着开发者是在教你如何保持对游戏的兴趣,而不是同你一起体验。“我认为这是对开发者如何同玩家进行互动的曲解。”

所以在单人游戏中,开发者应充当玩家2的角色。“玩游戏”是大家不要互相残杀的一种共识——但如果你将其完全归结于不要伤害对方,那么游戏就会失去趣味性。Foddy表示:“那是电子游戏版本的夺旗橄榄球比赛。那么我认为你不如去制作真实的足球类电子游戏。”

如果你这样做,Foddy指出:“你就是在同玩家一起体验游戏,而不只是为他们提供一个自娱自乐的游戏场景。”

不用过分担心挫败感和游戏测试。他指出:“也许你不该过分关注人们的看法。我想,如果Marcel Duchamp制作了游戏教程,那他是否会将其添加到游戏中?他不会专注于测试自己的游戏。”

Foddy总结道:“不要削弱整个游戏体验。我想艺术本身就是困难的,我想它应该是痛苦的、令人厌烦的。比起音乐或其它艺术,游戏应该更加困难、更令人厌恶,因为游戏就是更加复杂的机制。所以,电子游戏不应该太轻松。”

篇目6,游戏功能的趣味性远胜过内容的多样性

你现在手中有一个机制,假设是一个能够掷飞镖的机制。而且你需要在1周内将此呈现给大众。

此掷飞镖机制也许有不错的界面。镖盘也许过小或过大,或者光线略有不足。飞镖也许是个不错的构思,但内容的执行方式有待改善。

此时,你已设计出一个功能,但功能不怎么有趣。要将其变得颇有趣味,你需要投入4天时间。

throw dart from kccollegegameday.com

你可以改善飞镖,将其变得有趣。创造优质UI,设计杰出的物理模式和控制装置,再来就是丰富的画面,总之,你可以打造出一个有趣的功能。

这里的操作涉及3个层面:确保输入内容合理分布于用户地图中,这是基于“黑盒”角度,也就是所谓的飞镖机制;确保飞镖机制本身能够提供有趣的重复挑战;确保黑盒的反馈信息既生动,又富有教育意义,这样用户就会更擅长飞镖。所有这些都非常困难。

然后你就面临一个选择。在将飞镖变得富有趣味之后,你只剩下3天时间。你可以选择融入一个台球桌,或者你可以在飞镖中添加内容。这些内容就是新飞镖类型,更多类型的飞镖游戏等。它们不需要你添加新的机制,只会需要其他类型的数据。这里不会有太多的新代码(游戏邦注:新代码存在带来漏洞的风险)。若你在此投入3天时间,你可以制作最优秀的飞镖游戏。

你也可以转而选择引入台球桌。但若和之前的飞镖一样,首次尝试觉得这并不怎么有趣结果会怎样?那么你就拥有一款不错的飞镖游戏及一款蹩脚的台球游戏。

哪个会更好呢?创作出最优秀的飞镖游戏,或是获得一款中等飞镖游戏和一个糟糕台球桌元素?

添加功能能够带来新的趣味性,但趣味性源自于调节和平衡。并不是说你融入一个台球桌,趣味性就会神奇般地出现。

按照顺序,我需要先处理黑盒,然后是输入内容,最后是反馈信息。我无法通过更优秀的支持元素将糟糕的机制变得更杰出,虽然我可以将其变得更生动,但这通常无法赢得玩家的芳心。

我会选择完善飞镖,然后承诺尽快融入台球桌。待到我真正融入台球桌元素时,我们呈现的是最佳状态的内容,而不是被迫在最后期限前融入这一元素。

在我的职业生涯中,我并非总是能够这么进行选择的。我也进行许多激进现实主义的设计。我也经常不得不迁就于糟糕的支撑元素和反馈信息。我们甚至还曾将非常优秀的机制弃置一旁,因为我们无法解决让反馈信息易于理解的问题。

我总是倾向选择精致的机制,是指变量和规则很少的机制。若你在游戏中融入众多这类元素, 它们通常会带来突发性行为,这能够带来趣味性。但若你着眼于创建简单系统,你更易于在此融入众多变量和规则,这会令这些元素显得有些粗制滥造。

我很擅于提出简单额规则的解决方案,当中有10%能够在初次试验中顺利运作。但这些天,我发现,改善和调整规则机制要比最初提出这些规则多耗费10倍的时间。

篇目7,趣味性是游戏设计中最重要的内容

作者:Gavin Verhey

我们很容易遗忘游戏设计中最重要的部分,这时常令我感到惊奇。如果所有人在设计时能够记住一个准则,那么我想整个游戏设计领域都会有所提升,某些失败游戏就有可能避免悲惨的命运。

我在与其他开发者面对面坐着讨论游戏机制时,我们总会提到某些内容是否有趣。但是直到某次参加开发会议时,我才意识到趣味性才是游戏最重要的内容。

但我们存在的问题是,往往尝试将趣味量化。在游戏设计中,有时过于注重量化会让你设计的东西失去趣味性。

当你在设计东西时,需要在工作结束后问自己“这是否有趣?”。多数情况下,只有部分人会单纯为了证明自己的能力去玩游戏。

我自己也会选择逃避那些无法从中找到乐趣的游戏,即便我知道自己能够获胜,但是我认为那种体验就像是在游戏中“刷任务”,娱乐根本无从谈起。

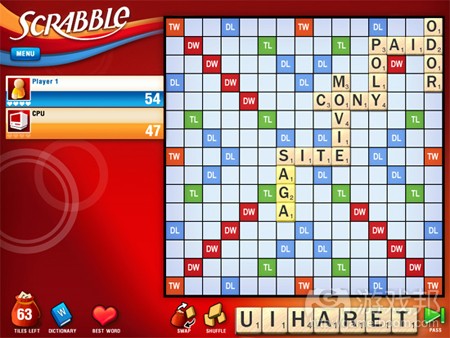

《Scrabble》便是个绝妙的例证。我很擅长驾驭文字,而且有推敲用词的习惯。于是,玩这款游戏便会让我感到很痛苦。我会花上15分钟分析界面布局,分析最适合填上的词,但是这样玩游戏对我来说毫无趣味性可言。这也是为何我不再经常玩《Scrabble》的原因,虽然这是我擅长的方面,但是游戏过程并不有趣。

当你在设计游戏的时候,很难把控趣味性。游戏趣味性的感觉因人而异。但是,在设计时你需要进行更深层次的研究。你必须在自己体验游戏时想到其他人会有何反应,在自我感觉和玩法感觉间取得微妙的平衡。从总体上说,《Scrabble》确实是款有趣的游戏,只是不适合我这种人群。

scrabble-for-ipad(from pcmag.com)

我相信,《万智牌》的成功得益于Wizards提升游戏的易用性和直觉性,这使得多数人能够体验到游戏中的乐趣。此外,该公司随后还制作了许多有趣的卡牌。改变设计规则和想法后,更多的玩家感觉到了游戏的趣味性。

当我们坐下来玩游戏时,除了正规的比赛外,我想每个人的目标都是享受快乐时光。如果游戏(游戏邦注:或纸牌)其他方面都做得很好,唯独趣味性不足,那么其仍旧比不上那些趣味性十足但其他方面表现不佳的游戏。

篇目1,篇目2,篇目3,篇目4,篇目5,篇目6,篇目7(本文由游戏邦编译,转载请注明来源,或咨询微信zhengjintiao)

篇目1,Behind the Scenes of Lucky Lady Games Studio

by Sandra Wong

At Lucky Lady Games, the most important question we believe we can ever ask about a game design is ‘Is it fun?’. You can have the most amazing artwork, sound engineering, technology,story line etc. but without the fun factor, the game is not going to succeed to its full potential (if at all).

Fun is fundamental to player retention, social buzz/share worthiness and monetization, so if you want to make a successful social game, focus on fun first, and everything else secondary. It is so critical in fact that all else can be overlooked to a degree and people will still play.

So how do you achieve fun in a game design?

The fun factor is definitely not something that is easily achieved and there is no one-fit-all type answer. Finding the sweet spot of where ‘fun’ meets ‘game play’ harmony is what every game designer should aim to achieve. To get there, we recommend lots of a/b play testing during all stages of the game design life cycle. Is it fun to you? Why and why not? What can you add? What would you like to see?

What may ‘seem’ fun in theory on paper, might not translate well in real time production. Depending on the type of game you are designing, different elements of what would be considered ‘fun’ varies.The secret is in game balancing… throwing every ‘fun’ game design element into a game will not guarantee more ‘fun’, it needs to make sense to the game play.

The psychology behind ‘fun’ is very similar to asking ‘what makes this game addictive’?

Here are some common game design ‘fun’ elements/hooks:

The High Score

The high score is one of the most recognizable hooks. Trying to beat the high score (even if the player is trying to beat his own score) can keep a player playing for hours.

Beating the Game/Leveling Up

The desire to beat the game or level up keeps players wanting to keep playing.

Role-Playing

Story line & escapism is a great way to engage players.

Discovery

Used mostly in RPGs (role-playing games). EG. World of Warcraft – a good portion of the game is spent exploring beautifully designed imaginary worlds. This thrill of discovery (even of places that don’t really exist) can be extremely compelling.

Relationships

Online role-playing games allow people to build relationships with other players. For some, this online community becomes the place where they’re most accepted, which draws them back again and again.<br />

Meta Games

Sometimes the actual game play might not be the fun element of the game. Eg. Farmville, one meta game is the social aspect. ‘Ask friends’ for help and items to build your Barn, might be more fun than actually farming.

Action

Moving blocks, dodging missles, spinning the reels… all games require some kind of player interaction.<br

Randomization

Opening boxes, rolling the dice, flipping the next card… the element of surprise is much more intriguing and engaging than known rewards.

Variables

Collecting & items, points, score board… people love to collect things. Give them a sense of achievement and purpose.

Control

Player choices, unlocking doors, new access levels… give them a sense of status & recognition for their efforts in the game.

Customization

Character appearances, dress up, weapon choices… personalization of characters makes players feel like they have ownership over the game and in turn a sense of belonging and loyalty.<br />

Balance

Game challenges and flow. Game needs to make sense: E.g, You can’t get to level 5 if you haven’t beat level 3.

Humor

Laughter is always fun so adding a little humor can lighten up the mood. The real world is too serious as it is.

Do you have a game/app design you would like to get feedback on for production and don’t know where to start? Feel free to send it to us at Lucky Lady Games and we will get you sorted out!

Until next time, try to add more fun to your life game!

Happy designing & playing.

篇目2,Debunking “Losing is Fun” Game Design

By Josh Bycer

If you’ve ever played any difficult video games such as X-Com, Spelunky, Dwarf Fortress and so on, you’ve probably heard the phrase “losing is fun” to describe them. Losing is fun means that the game’s design is meant to be overcome and a challenge to be conquered.

Personally, I hate when people use it as a defense of game design as it is more often than not used as a catch all for any kind of discussion on difficulty and design. Losing is fun can work, but in my opinion there is a very narrow margin of where it is acceptable design.

Balancing Progression:

To talk about game difficulty, we first need to talk briefly about the two kinds of progression in game design. Player progression refers to the player improving their knowledge and skill at a game. While character progression is about anything in-game that affects the player’s chance at success: Leveling up, items and so on.

What that means is that both forms of progression have a different feeling when it comes to failure. Failing at a skill based game means that you as the player haven’t reached the skill level needed to win and the problem is on your end. While failing at a character based game means that things outside of the player’s control were the reasons for their demise. Maybe they didn’t buy a strong enough weapon, or the random number generator during combat gave the enemy a critical hit.

The amount of control the player has over their success is a big factor when it comes to if a game is frustrating or not to lose at and where losing is fun is difficult to fine tune.

The Right Kind of Punishment:

Replayability is an important concept when it comes to game design and is a major component of difficult games or those where the player has to restart constantly. If your game is all about starting back at 0 each time, then the game needs to be very replayable.

In my opinion, for losing is fun to be correct, the game’s progression has to be on either extreme of progression.

In a skill based game like Spelunky or even those with light RPG elements such as Demon’s Souls, the player is the determining factor of whether they win or lose.

Failing in a game like Spelunky is OK as it always gives you a lesson to learn or something to make use of for the next time.

With character progression or strong randomized elements, like The Binding of Isaac or Dungeons of Dredmor. There is enough variability to the design that you don’t have enough control to win or lose that it’s not completely on you if you fail. Maybe an enemy got a lucky hit or you couldn’t find any powerful upgrades to win.

Depending on which case, either failure is controlled by the player’s actions or it’s completely out of their hands. This in my opinion is where losing is fun works as it means that either the player needs to get better or you just need to roll the die again and see what happens.

Ultimately there is one main detail of replayability that must be involved in a game for “losing is fun” to work: there must be some form of growth earned through each play.

The game must never reach a state where the game falls into a routine and there is nothing for the player to continue learning from.

Growth can be skill based IE: Player learns through trial and error the right way to beat a boss. Or character based: After experimenting with enough different builds, the player finds one that they like. When a game just becomes a grind to play, then “losing is fun” no longer works in my opinion.

My case in point and the reason for writing this post has to do with X-Com Enemy Unknown (and recently the expansion — Enemy Within).

I’ve heard people reference Enemy Unknown due to the choices and squishiness of characters as where losing can be fun, as it’s all about fighting an uphill battle. My problem with Enemy Unknown is that I’ve reached a point trying to play through on classic ironman where the game’s balance of character and skill based progression has become stagnant.

Due to the game’s cover system and randomness of enemy damage, the tactical side of the game or where skill is rewarded is too random for me to learn anything from.

While on the strategic side or character progression, I know what I need to do but not being able to rely on my skill during the tactical section, has a huge affect on progressing through the campaign.

As I mentioned in my analysis of Enemy Within, the feedback loop of the game is very polarizing, that if you start to fall behind at any point, it becomes very hard to recover. I know the right build order to go for in terms of base building and research progression to have a chance at winning on classic. But if I can’t get characters to be promoted quickly enough, or unlock the right researches, than I won’t be able to survive past the second month.

So my games either stall before the end of month two, or I get several months down the line and then win or fail based on my strategies and luck.

To give you an example, there are times where there is nothing more I could have done to save my characters and I lose an entire group due to the game’s randomness and therefore the game.

If your game is about promoting skill based progression, then the player’s skill needs to have enough impact on the gameplay. On the other hand, if your game is all about character progression and randomization, than the game must be so random that there isn’t any one way that wins every time.

“Losing is Fun” is a phrase that I hate to hear, as more often than not, it’s used to shield games with design issues from criticism.

If playing the game is a frustrating experience, then I don’t care how much fun losing is.

This is why games that are balanced around constant lost are either some of the best designed titles out there or horrible.

As the balance has to be perfect to keep the player invested in a game where progress is earned and not given.

篇目3,The Difference Between A Good Video Game and a Bad One

Stephen Totilo

During my first 25 years playing video games I had no theory about what makes a video game good. I knew the good ones when I played them. I just felt it.

Last year, however, I was forced to come up with a theory—a theory about what makes a video game good. I’ve been testing it ever since.

My theory is simple. Whether a video game is about shooting guns, flying planes, jumping over mushrooms, solving puzzles or rotating falling blocks, the game is a series of choices for the player.

A good video game presents a series of interesting choices for the player to make. Should the game’s choices be uninteresting—should they barely be choices at all—then the game is bad.

Events in the year 2011 had forced me to come up with some sort of theory about what makes a game good. The events involved Zynga, the company behind FarmVille, CityVille and, as I understood in early 2011, much of the eVil plaguing video games. The Zynga games, I’d heard, weren’t so much games as psychological tricks that baited players to keep playing by enticing them with scheduled rewards, not by entertaining them as games should, whatever that meant. Millions of people may have enjoyed Zynga’s games, I had heard, but the thinking was that millions of people didn’t know what was good for them. These things Zynga made weren’t just bad games, the critics charged; they weren’t even games.

A good video game presents a series of interesting choices for the player to make.How awkward, then, that Zynga was courting me throughout 2011 to play their games. They did that monthly, contacting me in my capacity as an editor at major video game website in the hopes that I would pay attention to their next big game, appreciate its improvements over the last big Zynga game and wind up with something positive to report about it. I did not want to play their games, but a reporter’s job is not to stem the flow of information. Yes, I told the Zynga people month after month, I’ll try your games.

Before the Zynga courtship began, I had only played FarmVille and only for a few minutes. The beginning of the game had presented no choices that interested me. It pulled me from one action to the next, telling me what to build or collect or what to wait for, giving me no sense that I was making any decisions of my own. It had bored me.

The Zynga people showed me FrontierVille. They told me about the game’s story. That didn’t make me want to play. They told me about Empires & Allies, which borrowed ideas from an old favorite, Advance Wars. Through its combat system I recognized that a player could lose a fight. The losing player, I realized, must have had a choice to make that brought them to victory or defeat. I was more interested in this game. But I tried that one and it, too, quickly bored me.

Then I tried Adventure World, a game Zynga would eventually re-brand as an Indiana Jones aventure. The hero of that series hates snakes, but an encounter with a snake in Adventure World is what convinced me that not only was this one a game, but it had the potential to be good.

I’ve tried to recreate my moments of discovery with some screenshots.

First, I entered one of the game’s maps and realized that I had a choice of where I could go. One path, to the upper left of the frame, would bring me toward bushes through which I’d have to slash.

I had no idea if anything was hiding in them. The path to the right would bring me to a piece of red treasure but also toward a snake that was moving in a pattern of its own and might intercept me.

I chose to move toward the treasure—and toward the snake.

I grabbed the treasure, and the snake closed in.

I decided to fight instead of fleeing. I discovered it was too weak for me. I killed it.

These were not the most fascinating choices in video game history, but they were choices. They were choices that would lead to immediately distinct outcomes. They interested me.

When the Zynga people showed me their next game, Mafia Wars 2, I knew what to look for: choices. The more the merrier, at least for Zynga, I thought. The Zynga people were getting better, I had decided. They were no longer making unbranching flow charts for their customers to click through; they were beginning to offer players branches; they were serving decisions that led to distinct consequences.

What Makes Tetris Great

As my idea about choices in video games coalesced, I began to look at my favorite video games differently. I love Metroids and Assassin’s Creeds, which I never doubted were video games. The Legend of Zelda: Majora’s Mask is my favorite game, though I’m pretty sure that Tetris is the best video game ever made. All of these games support my theory, Tetris most purely among them, which is probably why it’s the best. Each falling piece presents the opportunity for some basic but almost always-interesting choices: Where will I put this piece? Can I rotate it fast enough? Should I drop it swiftly? What is the next piece coming and how will this piece set me up for dropping that one? Do I want to set myself up to score a four-line-clearing Tetris? Etc. The choices come quickly.

The choices are always clear. The consequences are sometimes immediate, sometimes delayed. They are always clear.

The game isn’t really about falling blocks; it’s about a cascade of chances to make decisions.

Merihari… and Forks

I reached out to some of the smartest video game creators that I know and I asked them how they could spot a good game and distinguish it from a bad one. My theory was that the big thing was the presence of interesting choices, but what was their theory?

Dylan Cuthbert weighed in from Japan, which thrilled me because Dylan Cuthbert not only makes many video games that I like—Star Fox, PixelJunk Monsters, Digidrive, to name a few—but he has also worked closely with the top people at Nintendo’s Kyoto headquarters where many indisputably great video games have been made.

“Well to begin with, ‘beauty is in the eye of the beholder,’” he told me over e-mail back in the beginning of the year. “For example I think Dark Souls is an amazing game but others might disagree with me. However, for any game that someone thinks is really good there are a few common factors. For me those are: Aesthetics (not just artistic beauty), Polish, Engagement, Originality and final but not least, ‘Merihari’.

“‘What’s merihar?’ you are probably asking; well it’s a Japanese word that embodies rhythm+balance+distribution—for example. imagine a roller coaster ride without merihari, and it would just be a continuous downhill ride. That may sound good, but, actually without the tension of that initial climb, a fairly large chunk of the thrill is lost. It’s why boss fights work well in games. The stage before it builds up the tension. If you have a game that only has boss fights, the experience begins to feel shallow. (a game that sticks in my mind for doing this, unfortunately, is Omega Boost from Polyphony, a game that would have been much better if it had built up the tension before each battle)

Cuthbert: “For any game that someone thinks is really good there are a few common factors. For me those are: Aesthetics (not just artistic beauty), Polish, Engagement, Originality and final but not least, ‘Merihari.’””Probably the main thing, though, is that old favourite: tender love and care—when the entire development team has loved and cared for the game that alone can simply make all the difference.”

The merihari thing sounded right. Theory revision! Interesting decisions + merihari. Plus other stuff too, probably.

I got another response, this one from Eric Zimmerman, a game designer and academic in New York:

“I don’t think you can answer the question in simple terms, i.e. a certain kind of game design or a certain kind of player experience,” he told me in an e-mail. “I would have to answer that deciding WHAT constitutes a good experience for your players is part of the design problem itself. A game designer has to decide what success will be for her game. And then she has to design it!

“This idea of a game designer defining her own design problem is particularly salient for game designers, as opposed to other forms of designers (like architects or industrial designers) because our work is usually explicitly non-utilitarian. A fork designer can always fall back on the success of a fork design being the functional use of the fork: someone actually can use it to eat food.

Zimmerman: “Fork designers usually have their own aesthetic goals, for example. But in the case of (non-educational) games, the non-functional goals are ALL THAT WE HAVE.””But in game design, we have to create our own criteria for success. This might include aesthetic goals, goals for exploring or conveying ideas, commercial metrics, and technical innovations, etc. Of course, all of these kinds of goals are things that non-game designers can take on, too. Fork designers usually have their own aesthetic goals, for example. But in the case of (non-educational) games, the non-functional goals are ALL THAT WE HAVE.

“So game designers themselves decide what makes a good game good. And it can be unique for each individual designer, and for each individual game a designer might make. A game might be good because it makes you sad, or happy, or angry. It might be meant to relax players, or excite them, to grind them into a zen state or snap them into problem-solving alertness. A game designer might decide success is loving social interaction, or ruthless trash talking, or solitary isolation. Or success might be thinking about violence in a new way—or maybe thinking about violins in a new way.

Usually it is a stewy mix of a whole bunch of different and sometimes conflicting success criteria.

“And a designer’s idea of what success looks like for a game can even change as the game is being developed or after it is released. In fact the sweetest pleasure for a game designer can be seeing your game played in ways you never anticipated. That’s when your players teach YOU about what makes a good game good.”

This seems right as well, and helped remind me of my original quandary, which wasn’t to distinguish between good games and bad ones but to determine if something—specifically, the creations of the Zynga corporation—were games at all. Zimmerman did not address that specifically, but his comments about the goals of games helped me realize what it is that Zynga’s big FacebookVille games possess that makes it so hard for me to relax and just play them: their goal of making money for the people who created the game feels apparent every time I make a decision in one of those games.

Every time I make a decision, I use one of my rationed pieces of energy, bringing me another step closer to having to wait to continue (that’s annoying) or to bug my friends for help (that makes me feels like I’m marketing the game for Zynga) or paying for more energy (that feels like I’m losing a test of wills with a rich corporation).

Possible theory revision: A good video game not only contains interesting decisions but doesn’t include decisions that make me feel like I’m being manipulated/used/nickel-and-dimed.

Super Mario Decision-Making

In 2012, armed with my theory I’ve been looking for games that are full of choices. The Zynga people still call, and they still show me their games. If the game doesn’t appear to offer choices I haven’t been offered before—or if it doesn’t offer choices that lead to distinct consequences—I lose interest.

As I’ve hunted for games full of choices, I’ve honed my taste in first-person shooters and realized that I’m less interested in the ones that feel as if they pull me down a straight line and not give me a choice how to solve my problems (so that’s why I liked 2011′s Bulletstorm so much… every enemy encounter was ripe with multiple choices about how to win it).

I’ve realized that my low tolerance for Japanese role-playing games might be less due to the stories they present than to the lack of choices available in the ones I’ve played (so that’s why the Fire Emblems are my favorites and why I despise level-grinding, the epitome of the uninteresting choice of how to spend your time).

My zeal for interactive decision-making has enhanced my appreciation for Angry Birds Space and explained my limited interest in the wonderfully-written but choice-limited Ace Attorney games.

I now crave from the games I play the choice to do radically different things to see what happens next. If I feel like I’m being funneled or forced to do only a certain thing next, I resist. I get annoyed. I dislike the game. This must be why I loved Portal 2 last year, a game that may have had just one solution to each of its puzzles but let me feel like I was experimenting—making decisions—as I tinkered with possible ways through. And this must be why I tired of Uncharted 3′s combat, which offered me the same choices against the same enemies ad nauseum.

When I say I now look for games that are filled with choices, I don’t mean that I’m always looking for BioWare-style role-playing games that are full of branching moral paths. For me, choice can involve having two different targets to shoot. It can involve something as simple and pure and being posed with the quandary of whether or not to jump.

A Mario level rushed through briskly is an encounter with a series of interesting choices.I’ve always been fascinated by the act of jumping in Super Mario Bros.. I consider it the most perfect activity ever put in a video game (how strange that it’s not in Tetris!). Mario’s ascent is associated with discovery. On his way up he might hit a block that will sprout a mushroom or flower that grants him new abilities. His descent is an attack. On his way down he squashes his enemies. When combined, the ascent and descent are also a necessary means of traversal used to pass bottomless pits or avoid carnivorous plants that emerge from green pipes. Every inch of a Mario level presents the player a string of choices, almost all of which compel the player to decide whether or how to use the ascent, the descent or both to one’s advantage.

A Mario level rushed through briskly is an encounter with a series of interesting choices. The best levels in the series are composed of a series of obstacles that, when approached rapidly, offer a delightful set of quandaries. Do I run and jump over this guy? But then what does that put me in a position to do to the next guy? Do I take this upper path? But then do I miss the power-up that was hidden below? Do I hope on this turtle and knock its shell into the next few enemies, do I hop across each of their heads? Etc.

Perhaps this idea of good games that present interesting choices is too obvious a theory. Perhaps it does not sufficiently sift gaming’s good works from its bad, to say nothing of distinguishing between gaming’s good work and its greats. The theory has aided me, though, because it has helped me respect myself as a gamer and made me more conscious of how a game will use my time. If it offers me interesting choices, second by second and minute by minute, I may enjoy it. If it does not, I’d have been better off not playing it. This is how I now distinguish the good games from what I believe are the bad.

篇目4,Toward a Philosophy of Game Design

David Ethan Kennerly

This is by no means the philosophy of game design, but these notions may help an aspiring game designer before he begins his work and in reviewing not just his work but the fitness of his goals.

What is the Sound of One Hand Designing?

“[Do not] mistake yourself for an ‘artist.’ Our goal is to create newer and more fun games. Art is not our goal.” Tetsuya Nomura, Final Fantasy character designerThe Entertainment versus Art debate flares perennially. These participants may be having fun, but the dichotomy is uniquely inappropriate to games. For example among MMORPGs, to Jessica Mulligan, fun subsumes art; whereas, to Raph Koster, art subsumes entertainment. I will challenge the dichotomy itself. Crafting fun is the art of the game.

To paraphrase Stephen King: Put your game design desk in the corner to remind yourself every day that Art supports Life, not the other way around. By the end of this article, we may disentangle the faulty dichotomy. After reconsidering what we think we know about a game, fun, and art we may come to discover that Nomura and Costikyan are correct:

“If you were to write a Seven Lively Arts for the 21st century, the form you’d have to mention first is clearly games.” Greg Costikyan

To begin disentangling, we need to come to terms with the game as a unique medium.

A Unique Medium

“Unfortunately, as similar as the two media are, the differences are real and compelling and the superficial similarities can actually make people LESS effective in new, game-oriented roles.” Warren Spector

Games are not like other forms of art. To define a game: if it uses points, has players and rules, it’s a game. Of course a game may be part of a service or a world or a community, too. To keep a game, as I use the term here, from being confused with all the disciplines that game theory has been applied to (economics, psychology, politics, empirical analysis), call it “a parlor game,” if the reader must. But Joe and Jane at the checkout counter call it a game.

As the sound designer for the Lord of the Rings: The Two Towers video game wrote: “It is unproductive to think of games as ‘interactive movies,’ although many people tend to think of games in those terms. Let’s be clear: games and films are different media. The techniques, processes, and skills involved in the creation of each are unique and not interchangeable. The metrics by which each is judged are also different, meaning that many of the properties that make for a good film would lead to a lousy game, and vice versa.”

Narratives, which includes most films, and games differ dramatically, because games don’t tell stories, players tell stories. A narrative is a passive experience.

One watches and feels but does not do. The audience is not the actor. In a game, the audience is at once the actor, also. Herein is a conflict of purpose. The author of a narrative must control the lives of the actors. Whereas, the designer of a game must abdicate control. To paraphrase Will Wright’s first advice for a budding game designer: Games are about players having fun; not about writers solving the narrative problems they want to solve.

Part of the problem is that an intellectual property rarely links a fine narrative to a fine game. Dungeons & Dragons is not J.R.R. Tolkien-in-the-medium-of-a-game.

American McGee’s Alice is not an adaptation of Lewis Carroll-in-the-medium-of-a-game. Go or Eleusis, which are puzzling, logical, and playfully deep, offers better comparison to Lewis Carroll. Reiner Knizia came closer with his cooperative board game of “Lord of the Rings,” which retains the spirit of the novel. But still “Lord of the Rings” is more of a novelty than a fine game.

Many game-movie crossovers, such as Wing Commander or Mario Brothers, failed and so did movie-games, such as Atari’s E.T. or Braveheart. Their lesson: satisfy an audience for a movie, a player for a game. A bleak road lies before one who seeks a movie experience in a game or vice versa. Although the fine game invokes something powerful inside the willing player, don’t look for J.R.R. Tolkien or Lewis Carroll in a game. He’s not there. Equally, there’s no Reiner Knizia, Sid Sackson, or Harold S. Vanderbilt of narratives.

A game designer can borrow inspiration from another medium but not techniques or values. For example, being inspired by the pace in a movie is far from learning how to pace a game from studying pace in a movie. When I’ve successfully borrowed from other art forms, it was only the inspiration. To fail to understand this may create a scenario where:

“[G]ame development is turning into a circus, costs are skyrocketing, users get bored faster than ever before, and the development of truly new games — new ways of having fun — has all but stopped.” Mr. Yamauchi, President of Nintendo

A fine game does not resemble any other medium’s fine art. To give an extreme example: What fine movie resembles ChuChu Rocket? It defies the qualities of other arts.

It lacks story, depth, and eye candy. Yet it is still a fine game. Fun comes in different flavors: Chess, Kungfu Chess, ChuChu Rocket, Bust-a-Grove, Bomberman, Pacman, Lost Cities, or more. Each is an active, controlled, enjoyed experience. The player makes things happen.

Understanding these varieties of fun expands the scope of a fine game. As we shall see, the game designer should subordinate other qualities of the game to the quality of fun itself.

From the Point of View of Fun

“From the point of view of fun, the type of all the arts is the art of the game designer.” Paraphrase of Oscar Wilde

When discussing the art of game design, fun is the yardstick—not realism, not novelty, not narration, not philosophy, not impressive technology, nor visual quality.

Let’s define the term. Fun, like many common words, is overloaded with various meanings. In Korean, the same word describes having fun, being entertained, and being interested. Americans often combine some of these words, too. Bear with me if mine varies from the conventional. I mean not the fun of watching an explosion on screen, as in a movie, but the fun of creating an explosion on the screen, as in a game. I mean active, controlled fun, as Patricia Marks Greenfield wrote: “They were unanimous in preferring the games to television. They were also unanimous about the reason: active control.” So fun, for here and now, is enjoyment where you directly impact the outcome at every move.

I use the term fun as Sid Meier, Will Wright, Tetsuyu Nomura, and Yamauchi do, which excludes non-interactive experiences. In a painting, song, movie, book, or TV episode, the audience does not, within the course of the episode, alter the outcome of the episode. In a fine game, the player alters the outcome with every move.

Many game designers have broad interests. Yet while musing on realism, virtual this-and-that, multi-protagonist storytelling, is fun for system architects, the art of game design is to produce what is fun for the player. Sid Meier cleverly put it in several interviews since at least mid-1990s, if not earlier. For example, an interview with Richard Rouse III: “We have, amongst our rules of game design, the three categories of games. There are games where the designer’s having all the fun, games where the computer is having all the fun, and games where the player is having all the fun. And we think we ought to write games where the player is having all the fun.”

A professional game designer, who sells games to a player, ought to follow Sid Meier’s lead and attempt to design games of the third kind. Diverse industry professionals agree. From story consultant, Brad Kane: “Last, but not least – games must be fun. No amount of emotional depth will save a game that is boring.”

To online world designer, Starr Long: “Fun should always win over realism. These are games after all.”

To indie developer, Perry Board: “Don’t forget fun for the player. Your overall objective is to provide enjoyment. Everything you do should somehow be centered on that goal. ”

To pencil and paper designers, Monte Cook, Jonathan Tweet, and Skip Williams: “[They are] all powerful motivators. So, of course, is fun. Never forget that last one.”

To board game designer, Reiner Knizia: “[The game] is just a platform for the people’s enjoyment.”

Invoking fun does not require a fine game, but a fine game does necessarily invoke fun.

An Upward Spiral

“Humanity has advanced, when it has advanced, not because it has been sober, responsible, and cautious, but because it has been playful, rebellious, and immature.”

Tom Robbins

It would not do well to exclude fun, at least a few of its well-mannered incarnations, from sacred experiences. Fun, we shall see, is a precious instinct.

Game playing has roots older than the human species. Young mammals play. They don’t have specific rules, so they’re not games. But mammalian play behavior shares more in common with human game behavior than movie watching shares with playing a game. Play behavior may even be connected to the evolution of intelligence. Darwin’s early description of evolution resembles a game. We generally recognize our instinct to play as a feeling of fun.

If so, then fun is not low. It evolves sophisticated strategies. The old adage of a fine game, a minute to learn, a lifetime to master, is true because strategy begins simple and becomes complex. This same instinct is a compelling force toward science and art. Fun is a root of creativity. Einstein began math only after his uncle introduced him to it as a game of an investigator capturing a wily thief, wherein the solution was the capture. Discovering the nature of light in a gravitational field is not a simple pleasure, yet fun may have been its original fuel. Feynman won the Nobel Prize when he was pursuing a thesis that he described as the sort he enjoyed—he had fun at.

In the fine game, fun intersects fine art. By fine art, I mean basically great art: fine art is the final art, or the most perfect of the arts. There is a quotation:

“The more I study the smarter Aristotle gets.” In a fine game, the more the player studies the deeper the game gets. Once a player knows the perfect strategy in a game, such as tic-tac-toe, no amount of play will reveal a better strategy. When the game ceases to teach the player a new lesson, the game stops being fun. The mind engages in a process of learning, in an education about a special system when playing a game. When perfected, there is nothing new to learn. Whereas, in Lost Cities, Go, or any fine game, each iteration teaches a new lesson. New strategies unfold. Weaknesses in old strategies appear. This is a kind of wonder that precedes discovery. This shares the impetus of science and art.

So fun is the art of the game. It is a high goal. It is noble. It is not necessarily base. It is not necessarily a simple pleasure. Whosoever plays earnestly at a fine game ascends an upward spiral of intelligence. Even the strategies for choosing playing strategies evolve. The enabling goals within the span of the game themselves change. And once so involved, one is learning, “To be able to be caught up into the world of thought—that is to be educated.”

Playing the Human Condition

“He deals the cards to find the answer

The sacred geometry of chance

The hidden law of a probable outcome

The numbers lead a dance” Sting

Paul Schwanz was looking for something finer than the experiences he’s had in some games: “What does interactive entertainment have to offer that can be compared to

something like Steinbeck’s Of Mice and Men, Coppola’s The Godfather, or Shakespeare’s Hamlet?” Raph Koster, a MMORPG creative director, held a similar opinion: “If we want to go on a crusade to fix something, how about we fix the fact that your average cartoon does a better job at portraying the human condition than our games do?”[26]

A fine game does portray the human condition. Here are three examples:

1. Spades.

2. Seven-card stud poker.

3. Chess.

1. Like Steinbeck’s classic, “Of Mice and Men”, Spades is a two-player struggle of the lower-class worker invented around the Depression Era in the US. It’s been enjoyed for many decades by working-class men in situations much like many of Steinbeck’s characters. In the game, the partners bid on what points they can make, not unlike such plights of the Depression—and post-industrial labor in general. I don’t think it was a coincidence that my Army mates, at multiple duty stations, played Spades during downtime. A good Spades player learns a lot about the condition of the post-industrial service-oriented laborer. He learns that self-evaluation and teamwork trump individual excellence.

2. Seven-card stud poker is the penultimate game of American Business. Poker teaches the art of statistical speculation and bluffing. The movie Pirates of the Silicon Valley was fond of depicting Bill Gates as a good poker player in college as foreshadow to his business success.

3. Hamlet and Chess share equal footing. In playing Chess one realizes much about the state of feudal and post-feudal politics. Human life exists in freedom of movement. Each player gradually negotiates, with each move, for freedom of movement of their Principal. Bishops are bound to devour members of their own dogma (be it black or white), while the plight of the majority, the Pawn, is that he has the least freedom of movement of them all.

The musician Sting hinted at a perspective on a game from which to gain insight into the human condition. One who goes beyond the narrative media’s mindset may watch “[t]he numbers lead a dance.” Sessions of Civilization (Sid Meier), Chess, Go, Settlers of Catan, and Diplomacy have included holocaust, murder, power addiction, territorial threats, and economic depression. To those inclined to perceive, the fine game reveals, “The hidden law of a probable outcome.”

A fine game gives insight into the human condition, if you believe: The world resembles a game, and all of us are players—our moves finite, our consequences irreversible.

篇目5,The benefits of making your players suffer (and maybe throw up)

By Brandon Sheffield

Bennett Foddy, creator of QWOP, GIRP, and CLOP among others, likes to play with his players, and he suggests that more of us should be doing the same.

At the top of his talk at IndieCade on Friday, he asserted, “I’m going to try to convince you to put more suffering in your games.”

Learn a lesson from the Olympics, he says – it’s all about the suffering. It’s all about the pathos of second place.

“Nobody cries when they come second in a video game,” he notes. “Nobody lays down and cries. Why not?”

In track and field video games, “The way that you run is to either hammer a button really fast, or waggle a joystick really fast,” he says. “There’s no joy in that, the joy is in the panic – in your friends watching you injure yourself as you hit the button.”

“It’s not just that games are easier – though they are,” he says. “To me it’s that games these days are more comfortable. There’s less discomfort. My worry is not that games are getting too easy, because easy games can be wonderful. My worry is that games are getting too comfortable.”

What’s so good about suffering anyway? “When you’re suffering in a game, it makes failure matter,” he says. Counter-Strike uses boredom. If you fail, you have to just watch everyone else play, but frustration is more widely used.

“It makes success matter if there’s suffering in the game,” Foddy says. If you get to the end, you feel like this huge weight has been lifted. Thus, “this talk is a love letter to games that put you through Hell just for the sake of it,” he says, “because we enjoy the suffering itself.”

“Often when I start designing a game, I start by thinking about the aesthetics of the input,” he says. Would the interaction be fun if there were no game? “Most sports pass that test,” he says, noting that playing catch is fun even without rules.

One example is drumming your fingers on the keyboard – it’s sort of inherently satisfying – and that became the inspiration for CLOP, which uses the H, J, K, and L keys.

“I’d like to have an anti-ergonomic game where it’s physically challenging to play the game, and you could say to your friends ‘I played for three hours, and I had to go to the hospital,’” he said.

Foddy has been researching pain, confusion, and nausea in games, to make games that give players those sorts of feelings.

Wolfenstein 3D makes people nauseous, but it doesn’t make you feel good. “The reason I don’t feel good about it is that it’s not the point of the game,” he says. “I think you could make a game where nausea is the point of the game, and people would enjoy it.”

Motal Kombat gives you Fatalities, as an example of humiliation. “You might think that’s for the pleasure of the winner, but I don’t think that’s right,” he says. “The computer does it as well.

I’m supposed to be enjoying it as a player, even on the losing end.”

Ultimately it’s all about playing with the player, as a developer. “The reason I’m cataloging these various dimensions of suffering, is why would frustration feel good? Why would confusion or humiliation be nice?” he posed. “I think one reason is it represents the developer playing with the player.”

The idea among many developers is that confusion is an engineering failure. This means developer is teaching you how to stay interested in the game, rather than playing with you. “To me that’s a warped way to look at the interaction between the developer and the player.”

So in a single player game, the developer should be player 2. “Playing” is just an agreement that you won’t kill each other – if you take it down to completely not hurting each other, it loses its teeth. “That’s the flag football of video games,” says Foddy. “I think you should make the real football of videogames.”

If you do this, he says “you’re playing with the player, rather than providing an environment for players to play with themselves.”

Don’t worry too much about frustration, and playtesting. “Maybe you shouldn’t care so much about what people will think,” he posed. “I wonder if Marcel Duchamp would’ve put a tutorial into his video games, if he made them? He wouldn’t have focus tested his games.”

“Don’t water down your games. I think art should be difficult, I think it should be painful, it should be nauseating,” he says. “It should be more difficult, more nauseating than music or other art because it’s more complex,” he concluded. “Don’t make the easy listening of video games.”

篇目6,Fun vs features

You have a system. Let’s say it’s a system where you can throw darts. And you have to open your bar in one week.

Throwing darts might have a bad interface. The dartboard might be too small or too big or poorly lit. Darts may be a perfectly nice idea, but the implementation of it needs tuning.

At this point, you have a feature, but not fun. It’s gonna take you four days to make it fun.

You can refine darts, get it fun. Make the UI good, have a great physics model and control, great graphics, and in general, you can get it to where you have a fun feature.

The exercise here is going to be threefold: making sure the inputs afforded to the user map well to their view of the “black box” that is the darts system; making sure the darts system itself offers interesting repeatable challenges; and making sure that the feedback from the black box Is both juicy and educational, so that the user can get better at darts. All this is hard.

Then you face a choice. Three days left, if you made darts fun. You can either go implement a pool table, or you can add content to darts. Content would be new kinds of darts, more kinds of dart games, etc. They don’t call for a new system, just other kinds of data. Not much new code (and new code runs the risk of introducing bugs). You can make the best darn darts game in the country if you spent the three days on that.

The pool table, you could get that in instead. But what if it’s not fun on the first try, just like darts weren’t? Then you’d have a decent darts game and a crappy pool table.

Which is better, having the best darts game available, or having a middling darts game and a bad game of pool?

Adding features offers the potential for fun, but fun comes from tuning and balancing. It isn’t magically there just because you got a pool table.

In order, I would have to tackle the black box, then the inputs, and finally the feedback. I can’t make a bad system much better with great affordances and while I can make it juicy, it usually won’t hold players.

I would choose to polish up darts, and promise to get a pool table in there as soon as I can. And when I do put in the pool table, it’ll be as good a game of pool as we can make rather than being rushed to fit in before the bar opens.

This isn’t the answer I would always have chosen in my career. I have done plenty of kitchen sink design. I have also settled for poor affordances and feedback far too often. I have even had perfectly wonderful systems be unusable because we could not figure out a way to make the feedback comprehensible.

I’ve always leaned towards elegant systems, meaning ones with few variables and few rules to them. When you populate a game with many of these, they very frequently end up leading to emergent behavior, which can be quite fun. But when you lean on the creation of simple systems, the temptation is even greater to have lots of them in your game. And that can and will lead to most or all of them feeling unpolished and unfinished.

I’ve gotten good enough at coming up with simple rule solutions that gosh, almost 10% of them work on the first try! (Yes, read that as sarcasm aimed at myself). But these days, I tend to assume that it will take me ten times longer to polish up and tune that rule system than it will to come up with the rules in the first place.

篇目7,Having Fun: Why Fun Matters

Gavin Verhey

It often surprises me how easy it is to forget one of the most important aspects of game design. If everyone who ever designed just kept one principle in mind, I think the world of design – and likely the fate of some failed games – would be much better on the whole.

Let me back up to when I started thinking about design with this in mind.

For a few months, I’ve been helping develop a game with Jonathon Loucks for Skaff Elias and a few others. What immediately struck me as I entered headfirst into the fray is how we talked about the game.

At first, I didn’t notice. I’d be sitting across from Jon, talking about mechanics, and we’d mention how fun or unfun something was. But, as a pair of individuals who are around each other a lot and who regularly speak in these terms, it didn’t soak in immediately. It wasn’t until I was in a development meeting and Skaff started talking about how “fun” something should feel that the most obvious thing hit me upside the head.

Being fun is important.

Now, this seems obvious. We all try on some level. However, the thing about fun is that we often try and quantify it. Years of working in writing taught me to weed out terms that weren’t descriptive enough. The eyes of my poetry and prose professors unleashed invisible yardsticks on your wrists if you so much as mentioned “the flow” of a poem. After all, flow on its own meant nothing. There was always a way to pull out exactly what you liked with an increased description. However, in game design, sometimes too much pulling apart and quantification leads to stripping fun away from whatever you are designing.

But fun? Sometimes fun is just… fun. There’s not always good reason to describe it – or even a need to.

When you design something, at the end of the day, you need to be able to stand back and ask yourself, “Is this fun? Is this actually enjoyable?” For the most part (yes, I realize there are always exceptions) only one player group will want to play something simply because it proves themselves as people who can correctly identify value – the Spikes.

Even then, as someone who is partially a spike, I will often shy away from things I don’t find fun even if I know I can win with/at them simply because games become a grind otherwise.

A great example is Scrabble. I’m pretty good with words and have a propensity to figure out which words to put where. The problem? It’s excruciating to do so! I’ll look over a board, tank for 15 minutes, analyze the situation from every possible angle, and come out with a good play – but it’s absolutely no fun for me to do so. That’s partially why I don’t play Scrabble as often anymore – it just isn’t fun despite it being something I can be good at.

The problem is that’s hard to judge when you design something. There are competitive Scrabble players who thrive on figuring out the perfect word. Perhaps I am an oddball spike exception. However, what’s important is not to project your sense of fun onto other players’ sense of fun. Fun is normally something you have to look on an individual level. In design, though, it’s something you have to look at on a deeper level. You have to be able to look at what you’re playing and see how it applies to other people who haven’t even tried it yet. Will Timmy find it fun? Will Johnny find it fun? Will Spike find it fun? It’s a tricky balance. Scrabble is definitely a good, generally fun game overall, even if I personally don’t find it fun, because it has something for each group.

I believe Magic has had increased success lately precisely because Wizards has made the game more accessible and intuitive, which, in turn, make the game more fun to play for most people. Additionally, they have been making a lot of fun cards lately. It hasn’t always been this way. Fortunately, the days of Time Spiral are over, some new design rules and ideals are in order, and the game is a lot more fun to a wider group of players as a result.

When we sit down to play a game, outside of major tournaments, I think everyone’s goal is to have a good time. If a game (or card) does everything else well but still isn’t fun to play it’s still probably going to be behind something that is fun to play even if it does a couple of other things worse.

I have a lot to say on the topic of what is and isn’t fun, and there’s far too much to fit into one blog post. Consider this an introduction to the “Having Fun” series and expect future posts will go into specific details in depth. I look forward to talking to you then!