万字长文,Sid Meier与策略性游戏设计制作相关分析

篇目1,阐述《文明》之父Sid Meier的游戏人生

作者:Jason Schreier

在Sid Meier成为如今大名鼎鼎的《Pirates!》和《文明》系列经典游戏之父之前,他还只是一名计算机黑客。

在80年代早期,这名才20出头的程序员还在一家名这General Instruments Corporation的公司就职,当时与他共事的是一名由空军飞行员转业的商人John Stealey。Meier在个人计算机普及各个家庭之前已从计算机科学专业毕业,业余时间喜欢看点黑客杂志,在自己的雅达利设备上捣鼓代码,创建自己的更改版《太空入侵者》和《吃豆人》。他曾经制作了一款太空游戏,并将其上传到自己的办公室网络,吸引了太多同事导致老板迫使他删除该游戏。

Sid Meier(from kotaku.com)

Stealey回忆道,那一年他们俩人走进一个电子产品贸易展览会。在展会的第二晚,他们在一个地下室偶然发现了一些街机游戏。Meier在每款游戏中都打败了Stealey。之后他们发现了雅达利的《Red Baron》,在这款飞行游戏中,玩家要驾驶一艘双翼飞机跃过抽象的地形轮廓和障碍。Stealey这名前空军飞行员知道这次自己肯定能赢。他坐在游戏机前一路打到了7.5万个积分,在街机游戏榜单上排名第三。

之后Meier也迎头赶上,得到了15万分。

Stealey表示“我当时太震惊了”,他居然能够超过前空军飞行员?于是他转身问这名程序员:“Sid,你是怎么做到的?”

Meier答道:“你在玩游戏的时候,我在记其中的算法。”

Side Meier常说的话就是,伟大的电子游戏是一系列有趣的决定:玩家会不断遇到有意义的选择。这种理念令Meier收获颇丰——他的许多游戏收获了舆论好评和商业成功。在2009年Develop针对9000多游戏开发者“心目中的终极开发英雄”调查结果中,Meier位列第五(游戏邦注:当时排名第一的是《马里奥》开发者宫本茂)。

Meier的游戏总是充满有趣的决定,它们也总是截然不同。例如,开放世界型的海盗冒险游戏,发生于葛底斯堡之战背景的即时战略游戏,管理铁路的模拟游戏等。Meier最近发布的游戏《Ace Patrol》是一款自上而下战略游戏,要求玩家操纵战斗机飞行员在世界第一大战的战场中击落目标。

当然还有著名的《文明》系列。

在充斥高达8位数预算以及华丽的电影艺术般的电子游戏世界中,这款已有20多年历史的《文明》所具有的视角在今天仍然令人惊叹。有些游戏让玩家控制角色、城市或军队,而《文明》则让你主导整个世界历史。你可以选择一个国家——美国、罗马、英国等等,引导他们从公元前4000年走向现代。在每个回合中,你都可以在2D世界地图上移动人民,建设定居点和城市,与竞争国家进行外交,研发新技术,灌溉农田和发动战争。

这一模式催生出5款主要游戏,数款衍生游戏(其中包括专注于北美历史的《殖民》以及科幻史诗《半人马阿尔法星》),以及无数扩展内容包。它还令“Side Meier”成为游戏界家喻户晓的名字:该游戏官方名称并非《文明》而是《Sid Meier的文明》。这个名称带出了所有权、趾高气扬的特点。我们很容易得此结论——PC战略游戏之父是一个具有自我意识的人,他是那种会将自己制作的每款游戏贴上姓名的人。

但Meier却是一个和蔼可亲,说话慢斯条理而友好的人,同事对其评价则是杰出、谦逊和低调的人。其设计师同伴和密友Jake Solomon表示,“我在Firaxis工作这13年共事的所有人中,没有人曾经与Side有过个人纷争,因为根本就不可能。他是一个很好相处的人。”

上个月,我在一个曼哈顿联合广场的一个寒冷的会议室见到了这位传奇设计师,。Meier亲切而富有活力,脸上挂着温和微笑,身着深灰色色羊毛衫。陪伴身旁的是妻子Susan,她不时插话提醒他一起重要事项,或者他忘记的事情。我们一起谈论了他的游戏,他的经历以及成功和遗憾。

Meier是一个虔诚的基督徒,他喜欢音乐,并且会在美国马里兰州巴尔的摩(Meier及其妻所居住的城市)的一所教堂演奏风琴。他在自己帮助成立的Firaxis工作室头衔是“创意开发总监”,这实际上意味着他可以随心所欲创造自己想要的游戏。有时候这甚至意味着他要开发自己的游戏,其他时候则意叶着向公司其他人提供自己的设计看法,为《XCOM》(游戏邦注:这是由Solomon主导的科幻战略游戏)这类项目提供帮助。

Solomon称“你可以随时去找他——他的门一直是敞开的。任何人都可以跟他聊天……他是个极受欢迎的人。他在工作中投入大量时间。如果你在周末找他,很可能会发现他的车停在外面,他还在办公室处理自己的最新想法。”

我问Meier这名已经年届59的元老是否想过退休的问题。他答答:“我觉得自己有点像退休了。我现在正在做自己想做的事情——我已经退休很久了。我仍然热爱制作游戏,所以从未想过这一点。”

对于电子游戏粉丝来说这无疑是个好消息:Meier具有制作极富成瘾性和令人愉快的战略游戏的娴熟技巧。他对历史很感兴趣,尤其擅长将古板或者老式的历史事件(游戏邦注:例如葛底斯堡战役或第一次世界大战)转变成一般游戏玩家所喜欢的通俗交互娱乐体验。

Solomon称“他很有才气,具有我所没有的天赋。我们很难找到像这种能够以如此方式看待世界的人,你可以抛给他一个游戏话题,我保证你在周末就会看到他拿出一个与该主题有关的原型,Sid就是这样一个对世界富有洞察力的人。他几乎可以在任何事情中找到乐趣。”

曾经合作开发《文明II》的资深元老Brian Reynolds表示,“他的想法与我们非常不同。这真是不可思议。他的睿智并不会给人带来一种‘哈哈,我比你聪明’这种得意洋洋的感觉,你可以从与他的交谈中感觉到他有多聪明。”

Stealey称“有一年我曾经给他一本关于南北战争的书作为圣诞礼物。在新年的时候他还给了我,我说‘Sid,你不喜欢这本书?’他答道,‘我已经把它记住了。’”

在《Red Baron》中打败Stealey之后,年轻的Meier告诉这名同事,雅达利的飞行模式游戏不错,但他还可以做出一款更棒的游戏。Stealey接过话茬,“如果你能,我就能把它卖出去。”

Hellcat Ace(from kotaku.com)

Meier没有食言,在数个月之后,他为Stealey带来一个名为《Hellcat Ace》的战斗飞行模拟游戏的模型。于是Stealey就出去把它卖了。这就是这两者合作的开端,并在之后十年一直保持这种合作关系。Meier负责设计和编程,Stealey就去游说当地的商店推销游戏。在一年之后,他们的销售额达到20万美元。Stealey辞掉了他在General Instruments的工作,在他们现在称之为MicroProse的公司中做全职工作。一年半之后,Meier也这么干了。

在之后数年中,MicroPeose制作和推广了一系列针对雅达利主机的飞行模拟游戏和街机动作游戏,例如关于二战的飞行游戏《Spitfire Ace》,基本的平台游戏《Floyd of the Jungle》以及直升机横向卷轴游戏《Chopper Rescue》。与许多最早的电子游戏公司一样,MicroProse更是一种暴发户而非专业运营的公司。

Meier称“我们将游戏装在袋子中,Bill会开车到商店出售。这是一个非常粗放的工作流程。”

Stealey回忆道,“我会打电话给电脑店要求购买《Hellcat Ace》。如果他们还没有这款游戏,我就会高声喊道‘你们到底是什么电脑店啊,这款游戏都没有?’然后就挂断电话。这种事情我每三周都会做三次,每次都假装是不同的人在问。在第四周我就会打电话说,‘你好,我是John Stealey。我是MicroProse的代表,我们有款游戏叫《Hellcat Ace》。然后他们就会喊,‘喂,喂,喂,大家都要这款游戏,你能不能帮我们弄到这款游戏?”

1983年,由于市场饱和,导致雅达利和Magnavox等公司受到重创,电子游戏行业也走向崩溃,但MicroProse仍可通过持续发布由Mieier设计的高质量游戏而获得成功——其中多为飞行模拟游戏,因为这正是二人最感兴趣的游戏类型。

数年之后,由于公司持续发展——据Stealey称“我们成立三年创收300万美元”,有人建议他们制作海盗游戏。Meier很喜欢这一理念,并且回忆起他与Stealey某次非常重要的谈话:

“Bill说‘我下一款飞行模拟游戏什么时候问世?’我回答,‘我并不是在做飞行模拟游戏。我在做海盗游戏。’他说,‘那太疯狂了,因为大家期待你下一款飞行模拟游戏……等等,把你的名字放上去。如果他们喜欢你的飞行模拟游戏,他们就会认这个名字,然后购买这款海盗游戏。’”

Stealey有个非常不同的看法:“我们在软件发行商协会的晚餐上见面,当时Robin Williams(喜剧巨星)也在场。他让我们连续两小时忍俊不禁。他走向我并说道,‘Bill,你应该将Sid的名字印在这些盒子上,然后将他捧成巨星。’这就是为何Sid的名字出现在《海盗》和《文明》上的原因。”

在1987年,MicroProse发布了《Sid Meier’s Pirates!》这款开放世界探索游戏,玩家在其中可扮演海盗,在世界中寻宝,制服暴动的船员,并赢取更多金钱。

Meier说道,“我们创造了这个可以让我们快速成像的图像工具。内存很有限,一切资源都有限,所以你得很有效率,但我们发现了一个生成这些图像的有效方式。我们能够在故事中图解每个场景。其质量有点像冒险书故事,我认为效果不错。”

结果游戏很成功,《Pirates!》赢得了诸多行业和杂志的大奖,并影响了之后一批游戏,其中包括Will Wright的《模拟城市》,而这款游戏后来又启发了Meier的《文明》系列。

Meier回忆起早期加州圣何塞的游戏开发者大会(GDC),当时他与Wright、《M.U.L.E.》设计师Danielle Bunten、大会成立者Chris Crawford以及其他50-100名游戏开发者齐聚一堂的情形。

Meier称“我们当时很高兴,基本上都谈论自己如何喜欢对方的游戏。大家彼此并没有任何合作关系,因为我们只想制作自己的游戏。”

这就是第一代电子游戏设计师,Meier说“我们试图开发一个产业。”

如果你玩过多款Meier的游戏,就会注意到它们有些共性:没有任何血腥元素。虽然Meier喜欢涉猎暴力历史事件,但却并不喜欢展示暴力,例如《文明》中的战争就以抽象方式来呈现,只能看到两军交战时的冲撞,直至一方消失为止。

Meier的游戏也因给予玩家多种选项而得名,不会只是线性地讲述故事。Meier喜欢提供让玩家创造自己的故事的情形。玩家可以自己创造美国消灭他国,建立一个全球帝国的故事,也可以选择成为加勒比海盗。总之,一切取决于玩家的选择。Meier称“我喜欢那种可以令玩家主导游戏方向的游戏,他们一般都会创造自己才懂的独特游戏。”

没有哪款游戏能够比《Civilization》更淋漓尽致地体验这一理念,这是Meier及其团队在《Pirates!》以及商业模拟游戏《Railroad Tycoon》(支持玩家建设和管理自己的铁路公司)之后开发的一款游戏。

Meier称“《模拟城市》为我们提供了这类建设模式的灵感,启发了我们游戏并不一定是搞破坏——-它们也可以是创造。所以我们就分别从《Railroad Tycoon》以及《模拟城市》撷取了一些想法,就衍生出了《文明》的游戏理念。”

今天,一个至少100人的团队也需要两三年时间才能完成一般影响的电子游戏。而Meier却告诉我,他们8-10人团队在一年内就开发出了《文明》。

他称“最后我们电脑里有640KB的内存,如果全满了,我们就完了。我们无法再加入任何代码,所以那时候的开发时间比较短。”

《文明》在今天被认为是早期的回合制战略游戏之一,但有趣的是,游戏早期的一次迭代却是在即时状态下进行,就像《星际争霸》和《帝国时代》一样。那些未发布的原型并没有达到Meier的要求。

Meier认为这款游戏“更像是《模拟城市》,你可以说我想在这里建一个村子,在这里开一个农场,这里还要做一些什么事情,之后就可以看着自己的人民在此逐渐忙碌起来。但它是一个更为被动的过程。更多时候是在看而不是做。”

所以他们就更改了工具,给予玩家更多控制权,也变更了游戏节奏:现在玩家不仅仅是等待游戏世界改变,而是改变世界。如果玩家不做决定,时间就不会前进。

Brian Reynolds当时才刚在MicroProse就职,他记得《文明》早期的模型曾经令他和同事们通宵加班。

Reynold称“这有点像是在公司中‘病毒扩散’——当时并非人人都了解这个词。突然间大家都开始玩起这款游戏,每隔几天都会出现一个新版本。我这个看起来像闲杂人等的22岁小伙子经过办公室的时候会说‘我有些新想法’。Sid非常耐心地倾听我对于《文明》的所有想法。”

Meier当时即将奔四,他表示“这是一个非常有趣的开发过程”。他将游戏规模缩小了许多——游戏地图原先比现在大两倍,游戏中有两种不同的科技树,他回忆起与副总监Bruce Shelley一起进行多次玩法测试的经历。

“测试颇具挑战性,因为你需要花很长的时间玩游戏。我们当时并没有太多测试员,所以我就成了主要测试员之一——我花了大量时间玩游戏,之后进行修复和更改。”

《文明》在1991年末面世。它历时数月才得名——当时还没有互联网,但人们一开始发现这款游戏,就像星火燎原一般扩散开来。Meier的这一杰作赢得了不少奖项,当时被《电脑游戏世界》杂志评选为“史上最佳的150款游戏”中的第一名。据Reynolds所称,其销量达80万份。

当Meier完成这款成就其事业的游戏之后,他迫切希望制作更大更好更具雄心的游戏。但他也知道这将极为困难——“我说如果我一直深陷这种想要超越以往的游戏,或者做出更大更棒的东西,我肯定会把自己逼疯。”所以他决定收手了,将以美国为主的《殖民地》和《文明》系列的掌舵权交给Reynolds,之后又去做自己的事情——音乐应用《CPU Bach》,支持玩家创造自己的乐曲(但这款游戏并不成功)。

与此同时,由于Stealey打算平衡公司预算,MicroProse面临企业结构调整。在1993年,Stealey将MicroProse出售给名为Spectrum Holybyte的公司。一年之后他离开了公司。Stealey回忆称“公司经营得很好,我们应该做得更好,我们有优秀的人才。我认为我们所有员工仍然为自己在MicroProse的日子而自豪。我们有大家庭的氛围。我们人人都有现金分红。我认为它在很长一段时间运营都很顺利。”

由于厌恶裁员和办公室政治,Meier以及Reynolds、还有设计师Jeff Briggs决定离开MicroProse并组建新公司Firaxis Games。

Sid Meier并不喜欢商务运营方面的事项,当我提及MicroProse新所有权的问题时,他对此保持缄默。Stealey之后告诉我,“Sid并不喜欢卷入这种事情,他根本不碰商务方面的东西。”

Solomon也表示,“Sid最开心的是在办公室写代码。”

也许这正是成立Firaxis工作室令Meier如此兴奋的原因——这样他们就是独立的,可以在无需担心上司干预的情况下自由制定创意决策。当时,Meier在电子游戏行业中已经建立知名度,该公司也因此迅速与EA达成合作,发布了《半人马阿尔法星》(发生在外星的《文明》衍生游戏)以及《葛底斯堡》(以南北战争为题材的即时战略游戏)。

Meier表示,“在Firaxis中的工作真是太有趣了。”

该公司有相当一段时间保持小型和敏捷性,以10-15人的团队制作游戏,但在过去15年中,其人员增长,规模将近120人。在2005年末,Firaxis被Take-Two Interactive(《侠盗猎车手》开发商Rockstar以及2K工作室母公司)所收购。

Solomon于2000年加入Firaxis,他称“这里所有人都很好。我们很重视好人。我们并不会因为性格不同起冲突,这一优良传统来自Sid。因为我们工作室100%起源于Sid Meier,他的性格对工作室的运营方式,以及人们的互动方式产生了极大影响。他的愿景就是我们公司的愿景。”

在过去10多年中,Firaxis继续推出了一系列《文明》续作和衍生游戏,其中包括瞄准主机的《文明革命》和重制的《殖民地》。去年改版的科幻战略游戏《XOM》(由Solomon主导)赢得广泛赞誉,获评Kotaku的2012年度最佳游戏。现在该公司则以《Ace Patrol》和iOS移植版《XCOM》进一步推动业务多样化。

过去15年中,Meier一直希望制作一款关于侏罗纪和白垩纪的游戏——“Sid Meier’s Dinosaurs”,但却没找到令其有趣的方法。这个主题可行,但他从未找到合适的玩法基础:恐龙会怎么做呢?只是相互斗争?游戏进程如何?

Meier表示,“我做了三个不同的原型。一个是即时的,一个是回合制的,另一个是纸牌游戏。它们都有点意思,但却并不那么有趣。”

他以非常类似于另一名传奇开发者宫本茂的语气说道,“玩游戏,然后调整和更改游戏,这就是我的开发方法。如果其他人也玩过游戏,然后说‘这很不错’,我就会问‘但你不再玩游戏了吗?’他们若回答‘不玩了,收起来了。’就知道这里面存在问题。如果他们仍然没有玩游戏,那就说明游戏还不够有趣。”

Meier的妻子Susan此时插话了。她一开始就一直伴随着Firaxis,最初是担任公司HR,现在则是她自称的“勤杂工”。她说,“看到在工作的人经常玩这款游戏,你就会知道自己走对路了。”

Meier笑着补充,“即使是他们并不需要玩游戏的时候。这就是一个很好的兆头。”

但他还是不能敲定恐龙的问题。Solomon在Firaxis的招聘面试时首次见到Meier,他回忆起当时与这名设计师一起玩恐龙原型时的情形。

Solomon称“他让我玩原型,我想认只是想以此收集反馈。我玩了游戏,并进行了一番讨论,而他关心的似乎只是我对这款游戏的看法,我是否觉得有趣,我会做什么更改。这听起来一点也不像是面试,我认为他可能是在以此试探我的性格——但这实际上又确实是一场面试,我体验了一个很棒的Sid Meier游戏小原型。”

但Solomon也无法提供令游戏更棒的点子。Meier将这种遭遇失败的理念和被抛弃的原型的情形称为“失望深渊”,这就像是放弃的感觉。(Solomon事后告诉我,Sid曾将游戏称为一系列有趣的选择,但制作游戏却是一系列心碎的失望。)

有时候他们可以摆脱这种状态,有时候却是令人窒息。

在Solomon加入公司后不久,Meier就告诉大家他放手了。他无法做出这款恐龙游戏。

Solomon说道,“所以他就回家了,我们连续两周没见到他。之后他将大家召集到一个小屋子里说,‘好,我现在要做下一款游戏了’。他将游戏名称打在屏幕上,它就是《SimGolf》”。

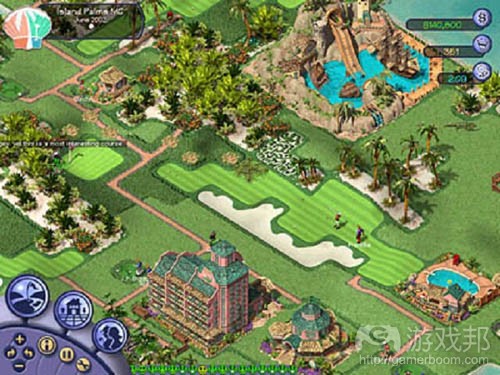

SimGolf(from kotaku.com)

这并不是关于《SimGolf》的视频或介绍文字,而是一个Meier刚刚做完的可行模型,已经支持玩家设计和创建基本的高尔夫球场。

“当时,Bing Gordon(之后成了EA高管)走进Sid办公室,坐下玩了一两个小时的游戏,出来后说道,‘没错,这款游戏会大卖!’每个看到这款游戏的人都说它非常棒。”

这种以原型为中心的理念一直是Meier制作游戏的方式,也是解释其成功的一个重要因素:他并不信任游戏设计文件,或者冗长的游戏运行方式描述。许多游戏开发者在开工之前习惯将想法和理念写在纸上,但Meier的方法却是亲身实践型的。

“Sid从来不需要撰写游戏设计文件,他不会跟你争辩自己想植入的新功能到底可不可行,他会直接回家连夜进行实践。第二天来公司就会说,‘现在可以试试这个新功能了’。你玩了之后,就可以不用看设计文件,直接展开与游戏有关的交流。”

Meier还因常与其他游戏设计师分享这些规则和格言而得名。

Reynolds表示,“‘找到乐趣’——这是Sid的口头禅。实际上是说,为了找到乐趣你得做些事情。乐趣并不会体现在纸上,至少电子游戏的乐趣是如此。”

Reynolds所描述的Meier令人不禁想起一个古老的笑话:“你如何雕刻大象?找一堆石头,削掉其中不像大象的部分。”你该如何制作一款好游戏?做一款游戏,移除所有不好玩的部分。

Solomon指出,“他曾告诉我一个令我至今受益的谚语。反馈才是事实,你应该这样看待反馈,因为它就是事实。你得开发这个庞大的系统或者这款游戏,他们会走进你的办公室,出来后说‘我玩了游戏,但感觉很无聊。’作为设计师最糟糕的事情是开始捍卫自己的设计或者与他人争辩。你应该接受他人所告诉你的事实。他们说自己觉得很无聊,那你就知道是什么情况了——你的游戏让他们觉得无聊。所以你就需要想想为何如此。”

这里也有其他规则。Reynolds想起自己一直无法忘怀的事情:如果你在制作电子游戏,并在某个数据上遇到麻烦——例如某个单位的损害值,要不然就让数据翻倍,要不然就将其减半。

Reynolds回忆称,“他并没有耐心试试增加10%这种做法。对于游戏设计师来说,那是一个很好的切入方法,因为常规的做法是谨慎地将数据调整一点点,然后更改了七八次才能令其生效。而如果你是将其翻倍,你很快就会知道扩大数据究竟是不是个更好的主意。”

这种方法很奏效。Meier的游戏如此杰出,以至于游戏玩家经常如此描述这些游戏:“我晚上8点开始玩《文明》,不知不觉就到凌晨4点了。”“成瘾”一词甚为流行,它通常带有对游戏的肯定意味,但上瘾也可能是件危险的事情。

所以我对此很好奇,在与Meier的聊天中提到他是否担心自己的游戏会对人们的生活带来有害影响?他的回答是:

“我们从论坛、与玩家的互动,以及同人们的聊天等各个渠道所得到的反馈是,这些游戏提供的是积极体验。这是玩家将原来看电视或干其他闲暇时间转移到玩游戏中的一种方法。这是一种空闲时间选择。所以我们关于玩家投入时间,在游戏中的收获,玩游戏锻炼脑力以及学习世界知识等方面所得到的基本上是积极的玩家反馈。

我认为下一个问题是,‘你会如何让游戏更不有趣?’这真好玩——在早期有些PC游戏设计中,我们曾经使用‘boss key’这种功能,玩家只要点击特定键,电脑屏幕就会弹出一个电子表格,你就可以假装自己正在埋头工作。所以我认为这是一个20几年前就已经出现的考虑问题。游戏就是要有趣。

对于任何娱乐形式来说,什么做法是合理或不合理的,这要由玩家或家长来决定。我们的目标是尽量制作出好游戏。我想这正是多数人所需要的。”

《文明》中没有奴隶,有些人批评该游戏忽略了这段历史。但这正是Meier作品的一个共性:虽然它们涉及历史,但却会忽略其中肮脏的部分。这正是Sid Meier制作游戏的原则,从《文明》到《SimGolf》再到他过去20多年所制作的游戏均是如此。

“关于是否应该给予玩家自由选择以及情感话题方面总是存在不少争议,我们的游戏极力避免的一个情况是让玩家处于道德困境(‘这个选择是对的,但这个选择才会让我获胜’)。这不是我们制作游戏的原则。我们希望让玩家在完成游戏时自我感觉良好。”

感觉良好,带有大量有趣选择的成瘾体验,这就是Sid Meier游戏的定义。也许这正是他们将其名字印在包装盒上的原因。当然也有不少人喜欢讲述关于道德挑战故事的游戏——去年由2K发行的《Spec Ops:The Line》就因为这一原因而备受赞誉,但Meier并不想制作这类游戏。他只想制作自己想玩的游戏。

但时至今日,Meier还没有创造出一款知名度堪比《文明》的经典游戏。在《SimGolf》之后,他重制了《Pirates!》,而后设计了第四款《Railroad Tycoon》——《Railroads!》。之后就是主机平台的《文明革命》,以及Facebook游戏《CivWorld》(已经停止运营),还有《Ace Patrol》。这些游戏虽然都很好,但并不像其杰作《文明》那样令人难忘。Meier告诉我他并没有什么遗憾——“除了没有先想到《俄罗斯方块》之外”。

“当我们制作《文明》的时候,并没有想到它会成为被我们所记忆的最出色的游戏。它是我们当时制作的最棒的游戏,我们认为它趣味十足。我们制作每款游戏时多少都有点这种想法:这将成为我们制作的最棒的游戏。有些游戏在玩家中引起了更大的反响,有些游戏则不然。我的原则并非制作超级经典的游戏,而是做出我们最好的游戏。”

篇目2,Sid Meier谈游戏行业发展及自身经验总结

作者:John Gaudiosi

Sid Meier已投身游戏制作近30年。这位传奇游戏设计师继续更新策略游戏题材,其中包括《文明V》扩充包和《Gods & Kings》。Meier的E3之行主要忙于两款Firaxis Games新作,即上面提到的《文明V》扩充内容和新版《XCOM: Enemy Unknown》(游戏邦注:游戏就1993年的经典回合策略游戏重新进行构想)。

自MicroProse Software时代以来,很多人就将Meier视作“电脑游戏之父”,如今他依然每天投身于游戏制作之中,目前担任Firaxis的创意开发总监。出自他手中的热门作品有《铁路大亨》、《席德梅尔之新海盗游戏》和《Sid Meier’s Gettysburg》,日前他接受采访,谈论当前的游戏行业态势。

sid meier from industrygamers.com

相比你刚入行时,游戏行业如今有何发展?

随着我们逐步理清要如何制作出更杰出的作品,以及因社交和手机游戏的出现及各种游戏化现象,我们获得更广泛的用户,行业未来将有很大的发展空间。我一直觉得这一阶段早晚都会到来。我们起初主要着眼于硬核用户和策略游戏,但随着我们逐步知晓要如何将游戏变得更通俗,覆盖更广泛的用户,行业就开始日益发展壮大。

这一发展趋势存在的挑战在于,要让玩家持续对游戏感兴趣,还有就是维持这一发展势头。我们需要促使他们持续返回新游戏和新构思中。时间会告诉我们,这一发展趋势是个行业周期,还是个永久现象。

作为元老游戏开发者,你的优势是什么?

作为老一辈设计师,我们曾接触过包含粗糙画面的传统游戏,无疑具备年轻设计师所没有的优势,因为我们竭尽全力让玩家认同除图像外的游戏元素。一个技巧就是,你需要制造悬念。这是你的承诺,也是玩家的期许。

查看当前游戏行业,什么最让你吃惊?

最让我吃惊的是越来越杰出的技术创新,但同时,我们也一直希望行业能够持续发展,引进新内容。这是行业富有趣味及吸引我们的地方。

Civ V Gods and Kings扩充内容 from gamesindustry.biz

你觉得Kickstarter将给游戏行业带来什么影响?

这是除App store、Xbox Live Arcade、PlayStation Network及其他小规模项目推广平台之外的另一新机会。如果你能够在此顺利运作,这将是个很棒的机会。过去几个月来,平台涌现多个成功项目。如果你拥有在故事方面颇具趣味的构思,这将是个非常不错的选择。

在Firaxis工作的每一天,什么最让你兴奋?

我非常喜欢制作游戏,这非常有趣。这就像是将一块粘土变成一个杰出的手工品。每一天都是这一过程的一部分。不清楚未来方向,逐步进行摸索是个挑战。这就像是《文明》当中的“再多一个回合”现象。这就像是探究我们将添加至游戏中的下个内容,看看自己如何将作品变得更杰出。在我看来,这里的趣味性在于,不知道我们每周要添加的是什么内容,而且能够进行体验和调整,经历游戏在你面前逐步成形的持续过程。

你认为5年后,游戏行业将发展至什么阶段?

我想,我们将进入出现不同新技术的阶段,尝试不同的技术运用方式。这曾出现在光驱和网络多人游戏领域,现在这将再次在社交和手机游戏的初期阶段中出现。在未来5年,我们将会看到基于不同题材的社交游戏。行业将呈现不同类型的社交游戏,玩家将把握其中规则和界面。移动平台无疑是项尚未被我们充分利用的技术。

那么手机游戏的机会何在?

目前的手机游戏基于5分钟快速点击模式。查看智能手机的所有技术,连网、GPS和摄像头,你就会发现,其中包含各式各样尚未被我们植入游戏体验中的元素。我觉得,未来我们将深入挖掘行业的可能性空间。没人知道未来技术将发展至什么程度。iPad是个很棒的硬件设备。我们积极探索基于这一平台的游戏设计,希望能够充分发挥设备优点。

在你看来,成功游戏的关键要素是什么?

游戏设计的一个关键原则是把握头15分钟。这些介绍内容需要富有趣味、令人满意及让玩家感到兴奋。你要让玩家知道他们的选择是正确的,你要奖励他们,让他们知道后面将有精彩内容。

在《文明》游戏的初期阶段,我采用即时模式,这意味着所有内容都会即时生成:我的第一个错误就将游戏设置成即时模式。我借鉴《模拟城市》的若干元素(游戏邦注:这是款即时游戏)。这非常有启发意义。但我们发现,在即时游戏中,玩家会变成旁观者。我们的原则是,“成为王者”。当我们将《文明》变成回合游戏时,玩家变成主角,他们是事件的主宰者。

你从游戏开发中积累的经验,有哪些是多年来依然适用的?

游戏就是个心理体验。我将我的游戏建立在铁路、海盗和历史之类的元素上,我极力将游戏变得逼真。内容越基于史实,越逼真,越符合实际就越好。在早期开发生涯中,我并没有将玩家脑中所想的东西思考在内。通过把握这一简单理念——游戏体验是心理过程,你的游戏将变得更杰出。

从Facebook和移动设备领域涌现的新玩家给游戏开发带来什么影响?

我曾在某个演讲中表示,游戏应该划分不同难度等级。我其实错了。《文明V》包含9个难度等级。随着玩家的进展,他们将变得越来越杰出,而且会获得奖励。你希望他们处于普通水平之上。游戏存在一个基本分歧情况:当你因玩家在战争中胜出给予他们100个金币奖励时,他们就不会质疑奖励。如果出现糟糕情况,如果遭遇挫败,他们的反应就大不相同。他们会抱怨称游戏存在漏洞。

在未来的游戏领域中,PC将扮演什么角色?

就历史经验来看,PC将依然是个强大的游戏平台。我们将看到新一代或新二代的掌机设备陆续问世。也许未来你的手表也能够体验游戏,谁也没法预测。游戏将继续跟着技术前进。未来5年将充满趣味。

篇目3,解析Sid Meier的游戏设计法则

作者:Soren Johnson

“好游戏是一系列有趣的选择。”大部分游戏开发者都知道Sid Meier的这条设计法则。

事实上,我的专栏合作者Damion Schubert在他最近写的关于玩家选择的文章中也引用了这句名言。

然而,在他的职业生涯中,Sid Meier还提出过其他几条游戏设计的法则。在他的工作室Firaxis Games工作的7年间(2000-2007),我多次听到他谈起。因为他的见解对设计师来说是相当实用的经验,所以我认为值得探讨。

加倍或减半

好游戏不是凭空做出来的,这就是为什么许多设计师都主张重复设计,也就是在这个过程中尽早制作游戏的简单原型,然后重复修改直到游戏变成可以发布的产品。

Sid把这个过程叫作“寻找乐趣”。开发团队在挖掘创意、测试然后根据反馈调整的循环中重制游戏的次数,通常直接关系到游戏能否成功。

在这个过程中,开发团队重制游戏的次数是有限的,开发者不应该浪费在小小的变动上。相反地,如果要调整玩法,那就变动得大一些,使之产生明显的影响。

例如,如果单位看起来太弱,不要降低它的费用5%,而是增强它的力量2倍。如果玩家受不了这么多升级,那就取消一半的升级数量。在初版《文明》中,游戏进展太慢,Sid通过缩小地图一半面积解决了问题。这么做并不是说调整后的新数值一般是对的——这么做的目标是使每一次重制都拓展出更广的设计领域。

把设计新游戏想像成探索未知的世界。设计师可能对存在于那个世界的东西会有模糊的概念,但没有实验和测试,这些假设都只能停留在纯粹的理论阶段。因此,对开发者而言,每一次重大改变都像开拓一片新大陆,在确定扎根筑营以前必须好好探索一番。

质量高于数量

Sid喜欢把这一条叫作“隐秘动作法则”,这与他在90年代早期设计的一款不太成功的侦察游戏有关:

我犯下的错误其实是,让一款游戏分裂成互相竞争的两款游戏。一款是动作游戏:玩家进入某座建筑做一些如寻找线索等事情;另一款游戏强调推理:在游戏情节中,玩家必须找出幕后操纵者是谁在哪里。

分开看,各个部分都能成为一款好游戏,但放在一起就会互相打架。玩家要解决迷题又要面对打斗,等到大战一场从建筑出来,玩家早就忘了自己要解决什么迷题了。隐秘动作不能把故事和动作良好地结合起来是因为动作其实太多了——玩家花了10分钟打斗,等到完成任务,早就不知道发生什么事了。

换句话说,即使游戏的这两个部分本身都很趣,但它们共存就会破坏体验,因为无论是哪个部分,玩家都不能专心玩。

这条原则指出一个大问题,也就是所有设计选择的选择产生于相互关系中,做任何一种选择在得到它的好处时也放弃了其他选择的优势。例如,选择制作策略游戏意味着选择不做战术游戏。因此,一个想法本身可能“有趣”但如果它干扰主体体验,那么它就不能使游戏更好。确实,这条原则显然就是《文明》系列为什么从来不篡改战斗的深度和战术。

然而,有时候多种游戏也是可能和谐共存的。Sid自己的《Pirates!》就是集战斗、航海和舞蹈小游戏于一体的成功案例。但是,这些体验总是很短的——大多只持续几分钟,不至于对扮演海盗这一主要体验构成干扰。各个小挑战都是通向更大目标——洗劫所有西班牙城市或拯救你失散已久的亲人的一个步骤。

Pirates(from cnet.com.au)

另一个案例是《X-Com》。它成功地将战术、回合制、组队的战斗游戏与策略、即时、资源管理游戏融为一体。与《Pirates!》一样,这种混合在《X-Com》中管用是因为游戏没有模糊焦点——与海军和入侵者的战斗。

高级的、策略性的主体游戏只是提供了一个松散的框架(游戏邦注:在这个框架中,这些战斗每场都可能持续长达半个小时)——这很重要。玩家不是为了之后的资源管理而与入侵者战斗,相反地,玩家是为了以后的战斗而管理资源。

多研究和利用现实题材

许多成功的游戏——《模拟城市》、《侠盗猎车手》、《文明》、《过山车大亨》、《模似人生》等,都采用真实世界的主题,通过围绕人们熟悉的概念构建玩法,从而扩大潜在受众范围。

然而,这种真实题材的游戏可能存在一个风险:使游戏充斥着大量生活琐事和炫耀设计师研究量很大的晦涩知识。这种倾向解释了为什么真实世界的主题这么有价值——玩家进入游戏时已经有现成的知识。

所有人都知道火药是强大的武器,警局能减少犯罪,劫车是违法的。正如Sid所说的:“不应该要求玩家阅读设计师读的书才能玩游戏。”

游戏仍然有很大潜力当作一种教学工具,只是并不是以许多教育专家所期望的方式。虽然设计师仍然应该注意不在要在游戏中犯明显的错误,交互体验的价值是简单的概念之间的互动,不是灌输大量事实和数字。

许多人都知道世界上最早的文明均发源于大河区,如尼罗河、底格里斯河/幼发拉底河、印度河。没有什么比《文明》中的若干简单规则更能有效地教授这个概念——在农业文明的早期控制能生产出最多食物地区。另外,一旦核心工作完成,研究可以充实游戏内容,比如用历史情境、背景叙述、或图像细节等。只要记住,学习新游戏是一个可怕的过程,所以不要因为以为玩家在开始游戏时已经知道所有知识,而浪费了熟悉的主题的优势。

乐趣是属于玩家的,而不是设计师或电脑的

文明4(from btz.cn)

对设计师来说,制作剧情导向型游戏是令人陶醉的,所以许多设计师加入太多专有词、生僻词和省略号,使故事变得臃肿。另外,复杂的、精细的模拟类游戏可能变得迟钝,如果太依赖算法模式的内部运作方式的话。如Sid常说的,在这类游戏中获得乐趣要么是玩家,要么是电脑,总之不是玩家。

例如,在开发《文明4》时,我们用政府类型做实验。我们的做法是,给政府显著的生产能力,但玩家不能选择研究什么技术、建造什么建筑、训练什么单位,而是依靠隐蔽的、内部的模式来模拟政府。

当然,在游戏之外,这个算法做起来说起来都很有趣。然而,玩家却不这么认为,因为享受所有乐趣的是电脑。所以我们把这个设定取消了。

进一步说,游戏需要的不只是有意义的选择,还有有意义的交流。如果玩家不理解自己的决定的后果,那么做选择就没那么有趣了。RPG在这方面通常做得很失败,例如,在玩家还没见识到任何真正的玩法以前就要求他选择职业或技能。

在了解各个职业的战斗方式和属性以前,玩家怎么决定自己要选择野蛮人、战士还是游侠?只有在知情且能产生可理解的结果的情况下,做选择才是有趣的。

因此,按Sid的话说,玩家必须“总是主角”。在开发游戏时,作为设计师的我们必须成为玩家的最有力支持者,总是认真考虑如何设计影响玩家角色以及玩家对潜层机制的理解的决定。

篇目4,Sid Meier分析让游戏选择更有趣的设计要诀

作者:Leigh Alexander

Firaxis创始人Sid Meier表示:“游戏是一系列有趣选择的结合体。”这是他过去所做出的陈述,并且他自己也意识到这一观点引起了各种争论。但是他始终坚持这是形容游戏设计的最佳方式,所以他在2012游戏开发者大会上进一步解释了这一观点,即什么样的游戏决策才能够吸引玩家,以及设计师需要明确那些内容。

这位《文明》系列之父表示:“我们总是能够很容易发现哪些决策不够有趣。”如果玩家总是选择3者中的第一个,那么这就不是一种有趣的选择;或者也不能算是一种随机选择。虽然某些游戏类型(游戏邦注:例如有赖于不同输入方式的韵律游戏或益智游戏)的关注重点并非有趣决策,但是不管怎样,Meier都相信自己最初的这一理念能够帮助我们更好地理解游戏这种媒体。

Meier继续说道:“在设计阶段这一理念非常重要。我发现许多游戏设计都是将其它游戏中的某些内容组合在一起。”大家可能会认为,如果那些游戏是有趣的,那么其游戏元素的组合体也必然是有趣的。

“但是很不幸的是,这种做法却并不总是奏效。相反,我认为如果游戏设计师能够仔细思考自己该为玩家呈现何种决策,玩家真正感兴趣的内容是什么,并围绕这些想法设计新游戏,也就是从玩家的角度进行抉择,他们肯定能够设计出更棒的游戏。”

文明(from c-evo.org)

哪种选择才算有趣?

一般来说,有趣的决策常需要玩家进行一番权衡,如获得一把强大的剑需要耗费500个金币,或者在赛车游戏中跑得最快的汽车往往更难以操作。而在Meier的《文明》中,创建一个防御单位建筑则需要玩家付出一定的资源才能发挥作用。

Meier解释道:“好决策要视游戏情境而定。当设计师在向玩家呈现游戏决策时他们必须清楚,决策必须符合游戏当前的情境。”《文明》中有一些复杂系统便呈现给玩家一些情境式选择,即何处呈现这些选择,以及玩家需考虑这些选择将对游戏进程产生的影响。

也有一些较为个性化的决策,它们取决于玩家的游戏玩法。例如,谨慎的玩家会选择创建一座安全的基地并慢慢扩展;而好斗型玩家则会投入更多精力去创建攻击型建筑。Meier表示:“这种有趣的决策设置必须让玩家能够表现出自己独特的游戏玩法。”

一般来说有趣的决策将能够长时间影响游戏(只要玩家总是能够拥有足够的信息并做出决策),而当早期选择在一段时间后开始破坏玩家的游戏体验时,开发者就需要对其做出适当调整而更好地匹配当前的游戏形式。

一种经典的决策类型是关于风险与奖励的权衡,即让玩家判断获得一定奖励前将会面临怎样的潜在风险。Meier说道:“我们几乎可以在任何游戏中发现这种决策类型。”而另外一种决策类型则是关于长期决策与短期决策的衡量,就像在《文明》中创造一个奇迹虽然需要花费玩家许多时间,但是却能为游戏的发展带来长远的影响,而创造一架二轮战车虽然不需要太长时间,但却不足以影响整体的游戏发展。

当提到如何让游戏设计适应不同玩家的游戏玩法时,Meier说道:“设计师很容易想当然地将自己的游戏玩法贯穿于游戏中,并且整个设计团队或开发团队也很容易从自己的角度去思考玩家的想法。”这就是为什么好游戏设计需要尽可能顾及更多选择和各种类型的游戏玩法。

Meier表示,《文明》的一大优势就是在短期,中期和长期事件中会同时发生多种情况。而玩家在游戏中的任务则是区分不同事件的重要性,为近期和长期目标制定相关策略,并努力让短期目标辅助实现长期目标。

定制功能也能够创造出有趣的决策,即使有时候这种功能只是让玩家为自己的城市命名或决定车子的颜色。Meier说道:“这种设置能够让玩家深度融入到游戏中。通过让玩家在游戏中做决策去表达出自己的个性,或表现自己独特的游戏玩法,这能够进一步吸引他们玩游戏。”

明智的选择

设计一个有意义的决策便需要确保玩家清楚自己所做出的任何选择;如果玩家做出选择但却因为不知道结果而陷入恐慌中,他们肯定不会认为游戏是有趣的。Meier建议:“如此看来如果能够提供给玩家大量信息反而更好,或者至少你应该让玩家清楚自己为何要做出这个选择。”

说到如何让玩家轻松地作决策就不得不提到游戏类型的相关惯例—–例如大多数射击游戏都带有标准界面,让玩家能够更加安心地做出选择。Meier提醒道,如果你的玩家在游戏中按压了一个按钮(与同类型其它游戏的设置一样),但是却出现完全不同的结果,“玩家定会对此感到不安。”

Firaxis的游戏中之所以会包含许多历史主题是因为这么做能够让玩家面对更多熟悉的信息。“你应该为玩家呈现他们所了解的信息,就像在《文明》中如果玩家碰到了成吉思汗,那么他就一定是个暴躁且好斗的形象;而如果你创造的是一款与铁路或海盗有关的游戏,你也可以将玩家所熟知的主题添加到游戏中。”

僵尸类游戏之所以如此受欢迎便是因为这类游戏的主题非常明确,不管是游戏动机还是僵尸本身的属性都是玩家再熟悉不过的内容了。“在这种类型的决策中你不需要为玩家呈现过多信息,因为他们本身就了解这些内容了。”

另一方面,当玩家做出决策后,游戏的反馈也很重要:“最糟糕的游戏反馈是对玩家的决策置之不理而继续前进。对于玩家来说,没有什么比自己做出决策却遭到游戏忽视更让人厌烦了。游戏至少应该提示玩家:‘我知道你的选择了,我会执行这个任务。’”就像在《文明变革》中,玩家很高兴能够在与其它区域首领协商时移动一些单位时获得游戏反馈。

反馈信息能够让玩家在游戏世界中的更有存在感。Meier解释道:“你必须让玩家感受到你知道他们的存在,你在游戏中始终陪伴着他们,支持着他们。你可以告诉玩家‘你是一个伟大文明中最优秀的首领’或者‘你是一名伟大的赛车手’之类的话语。不论是用声音,文本还是图像表达形式,这些内容都能够更加坚定玩家的游戏信念并让他们深刻感受到游戏的乐趣。”

玩家类型

为了为玩家创造出更多有趣的决策,设计师必须进一步理解各种不同的玩家类型。看重胜负的玩家希望游戏能够提供更高级别的内容;而看重类型的玩家则喜欢一些特定的游戏类型,追求那些自己所钟爱的内容,并讨厌各种偏差。这些玩家的反馈能够帮助设计师更好地理解类型惯例,但希望这不会因此束缚他们创造新内容。

有一些玩家希望能够理解所有的游戏法则,并引导出最佳的游戏结果。这种类型的玩家能够帮助你平衡游戏,因为他们的游戏目的是揭开并明确游戏系统。还有一些偏执型玩家总是认为游戏中的一切内容都对自己不利,就像他们会认为掷骰子永远都是不公平的一样。还有些历史迷们会不断批评游戏中的背景元素,并抱怨各种不符合原始资料的内容,或任何偏离历史背景的设定。

还一些总是纠结于自己遇到的任何不幸游戏体验的玩家。“你需要明确地指出他们所遇到的任何挫折,让他们知道为何会发生这些事以及他们下次该如何面对。因为对于这类型玩家来说,任何一件偶然事件都可能影响到他们的整个游戏体验。”同样也有一些带有评论性观点的设计师玩家,他们便更加关注于游戏中的任何细节问题,并琢磨为何这些内容与自己的创造有所差别。

设计师必须深刻理解各种类型的游戏玩家,从他们的反馈中寻找有价值的内容,并落实行动。

更有趣的决策

当你的游戏执行了一次有趣的决策之后,你该思考如何做才能让这些决策更加有趣。通过平衡风险与奖励选择;调整选择让它们更具有效力,提供给玩家适当的信息,或者给予玩家一定的时间范围做决定;以及整合游戏中的选择数量等行为都有利于优化游戏设计。当然了,你还可以为游戏添加一些不同的“调味料”,Meier表示:“这是游戏的呈现方式。要善于利用美术人员或文案人员的才华为游戏添加不一样的特色。”

Meier继续说道:“我们应该谨慎地处理决策的平衡问题。如果你在游戏中接二连三地设置复杂决策,这会让玩家感觉难以招架。而反之,如果你总是慢条斯理地给予玩家一些过于简单的决策,他们也会很容易对此感到厌烦。”

创造出更有趣决策的另外一种方法便是抛弃那些无效的决策。Meier说道:“如果你在反复尝试后发现自己所面临的是一些无效的内容,请果断地抛弃它们。也许有三分之一的内容是你应该删除的,但是不要对此感到心软,因为即使你现在不这么做,这些决策也会因为无趣而最终遭到淘汰。”

最后Meier还强调道:“要记住游戏并不只是关于各种决策。”我们不能因为过分强调决策的开发细节而忽视了为玩家创造一个有趣生动的游戏世界。将强大的游戏世界与有趣的决策设置结合在一起,我们才能有效且长期地维系玩家与游戏之间的关系。

Meier总结道:“将你所创造的神奇游戏世界与玩家其中所做出的各种有趣决策结合在一起,这才是一款真正的优质游戏。”

篇目5,《Sid Meier’s Pirates!》吸引人的六大原因

作者:Thomas Henshell

“优秀的艺术家会选择复制,而伟大的艺术家会选择窃取。”—-毕加索

《SidMeier’sPirates!》可能算得上是最重要的一款游戏,我花了大量的时间去玩这款游戏。现在我正致力于《Archamage Rises》,而我对于这款游戏的部分电梯游说内容便是“这就像是带有魔法师和永久死亡设置的《Pirates!》。”

pirates logo(from gamasutra)

我和《Pirates!》已经认识彼此好长一段时间。自从我将我的360KB的5.25英尺软驱放进我的Tandy 1000并运行它已经过了27年。我有一阵子未去接触它,直到本周日,我打开了游戏的2004版想看看它能够带给我什么启示。(游戏邦注:小时候我都不能在周末看电视,所以我便可以借此在游戏中自由地当一名“海盗”。)Firaxis的2004版便是重创早前游戏的内在优势去适应现代用户需求的有效例子。如果你玩了2004版,你通常也玩过87版,反之亦然。

以下是本周我所学到的对自己有帮助的内容,希望对你们也能够起到帮助:

与任何创造性项目一样,游戏设计/概念是源自一个清晰的灵感。在碰触键盘前我能够清楚地看到自己到底想要创造怎样的游戏。但就像独自处在风浪交错的开放海域的船只一样,游戏开发过程也会不断漂移。编程,美术选择,新功能等等所有决定都有可能偏移游戏的核心概念。我是独自一个人!所以我不能想象带有无数充满才能的开发者的AAA级团队是怎么做到这个的。

所以当我在War Sloop中作为一名荷兰人航行于加勒比海时,我遭遇了与《Archmage Rises》中完全不同的漂移。对于某些我需要做出的航线修改我真的感到很失望,但我却非常满足游戏的整体体验。

与Neo一样,Sid也为我们呈现了通向真正开放世界设计的方法

我清楚地写下了《Pirates!》可能是最重要的一款游戏。这是本周我的一个开发者朋友跟我说的,一开始我觉得这是一种荒谬的想法。但之后我意识到这一点都没错!

《Pirates》是世界上第一款开放世界游戏,并且是4种不同类型游戏的组合。我听到许多人将《侠盗猎车手III》称为“第一款”开放世界游戏—-但从创造性来看,它是比不上《Pirates》的。让我们来看看原因:

1.逼真的世界

不管有没有你的参与,《Pirates!》的游戏世界都很逼真。它模拟了整个加勒比海经济。欧洲列强将在这里相抗衡。城镇会遭遇发展与衰败。突击者或入侵者将摧毁城镇。城镇会因为模拟战争发生改变。州长的替换带动了经济的发展。有名的海盗(NPC)在世界各地周游,并创造了破坏。即使出发点一样的两款游戏也不会完全一样。

一个特殊的例子:一艘商船从圣胡安行驶到圣基茨岛,不管是出发港还是到达港的经济都会受到推动。如果船只在海上遇难,那么这两个港口也都会遭遇损失。城镇的经济发展决定了你能够获得多少钱去购买货物,以及能够出售/交易哪些商品。

在沙盒中是不存在中立的行动。不管你做什么,游戏世界都会发生相应的改变。

2.突发行为

pirates(from gamasutra)

《Pirates!》带有一些非常简单的规则。但这却是适当的规则—-所以伴随着所有模拟代理,你的突发行为也拥有了合理的存在理由。

我愉快地航行着,什么人都没看到,除了两个分别来自不同地方并同时朝着一座西班牙城镇发射大炮的法国人。我想不管是我还是开发者都不会预料到两个来自不同城镇的人会在我经过的时候同时朝着同一座城镇发动攻击。

同时,我决定攻击一辆特别的船只—-但当我到达那里时,它却非常靠近城镇了。所以我的海战便变成了海陆战—-这都取决于船只离开港口的时间。我们的路线交叉在一起,我不得不处理这些结果。

3.永久存在

当你抢夺船只时,城镇的经济也会受到影响。如果你支持其中的一个欧洲列强,它将控制你的加勒比海领域。你可以通过放手城镇或促使强大的运输船沉入海底而帮助城镇不断从一个国家转手到另一个国家。不管怎样每一种行动都带有持久的结果以及“我做到了这个!”的深刻感受。

这种存在感将在地图上不断加强。它呈现了你的行动在游戏世界中所发生的地点与时间。这是你在加勒比海域的故事;这是个人的故事。也是吸引我不断回到游戏中的元素。

4.不同效果

考虑到你只能作为海盗,所以基于限定类型的游戏拥有着各种不同的游戏风格。

首先,如果你属于行动导向型,你便能够通过掠夺船只并与船长战斗而赚钱。但如果你更有商人头脑,你便能够汇聚一大群商船并作为一个商人从一些注重生产的小城镇航向注重消费的大城镇。

你可以占领并控制游戏中的每一艘船。也就是你可以选择入侵一艘12枪的单槐帆船或者48枪护卫舰。做出不同选择所使用的战术也是不同的。

获得财产并与统治者的女儿结婚。反复做这样的事!这是我所知道的少数允许一夫多妻制的游戏。

5.程序生成任务

逼真的游戏世界充分利用了基于现状的游戏生成任务。

一艘运载着珍宝的船只上的酒吧女侍将前往附近的岛屿。或者一位控制者希望你陪同新统治者前往他所要到达的目的地。旅行者将卖掉藏宝图。

当我认为这些内容会不断重复时,我发现它们比《Destiny》的任务更吸引人。可能是因为如果我能成功护送统治者,世界就会彻底发生改变。而在《Destiny》中,当我下次射击时Vex仍会出现在那里。

6.意外故事

2004版的《Pirates!》带有一个再生/为你那被绑架的家人报仇的故事。你可以完成这一任务或彻底忽视它。

待在我自己创造的故事中会更有趣。我是作为一个将与西班牙人协商的荷兰人。有时候我会给北方带来灾害,有时候则是南方。有时候我将选择一个城镇并阻碍它获得外部货物,或平衡地扩散我自己的控制统治。

游戏的简单规则和逼真的世界让我能够创造自己的故事并体验能够打动内心的内容。在这里比我聪明的人将其称为从“游戏”到“软件玩具”的转变。这似乎是Sid游戏中常见的思路,这也是这些游戏能够经得住时间考验的原因。

窃取好的的内容

毕加索真正想传达的是什么?他提到了内在化艺术品的概念或类型,而不仅仅只是复制。复印件和记忆是完全不同的。就像在编程时,我们可能拥有同样的理念,但是表现出来的可能是肤浅复制vs深度复制。

当我说我自己正在制作带有魔法师的《Pirates!》时意味着什么?

我并不是说我在创造一款带有魔法师不断攻击商队去讨好统治者并与他的女儿结婚的3D地图的游戏。对于我来说这是一种肤浅复制。

我是在执行上述所提到的6大设计核心。我的大多数努力是专注于创造一个真是可信且活灵活现的幻想RPG世界。在这里贵族(也就等于统治者)将带有个性和野心。他们将根据其领域以及邻居身边发生的事去生成任务。作为玩家的你将决定想要支持哪个贵族以及想要在谁身上测试你的Fire Rain咒语。我在这里所谈论的是Sid做了什么以及我们该如何进一步使用他的方法。你拥有一个基地(你的魔法师塔),并且根据你的名声,贵族将派遣入侵者去攻击你!所以你的表现将影响你的个人安全。这是玩家在游戏中感受到存在感与永久性的一种方法。最终,我想要提供给玩家去传达自己的故事的能力。我希望借此能够推动我的游戏的成功并让更多人愿意不断回到游戏中。

篇目1,篇目2,篇目3,篇目4,篇目5(本文由游戏邦编译,转载请注明来源,或咨询微信zhengjintiao)

篇目1,Sid Meier: The Father of Civilization

Before Sid Meier was Sid Meier—the iconic video game designer whose name is stamped on classic titles like Pirates! and Civilization—he was just another computer hacker.

In the early 80s, the then-20-something programmer had a job at a company called General Instruments Corporation, where he worked alongside a gruff Air Force pilot-turned-businessman named John “Wild Bill” Stealey. Meier, who had graduated with a degree in computer science before there was a personal computer in every home, spent his spare time reading hacker magazines, fiddling with code on his Atari, and building his own versions of arcade games like Space Invaders and Pac-Man. At one point he made a space game and put it up on his office network; it hooked so many employees that his bosses forced him to take it down.

One year, as Stealey recalls, the two men went to an electronics trade conference. On the second night of the show, they stumbled upon a bunch of arcade games in a basement. One by one, Meier beat Stealey at each of them. Then they found Atari’s Red Baron, a squiggly flight game in which you’d steer a biplane through abstract outlines of terrain and obstacles. Stealey, the Air Force man, knew he could win at this one. He sat down at the machine and shot his way to 75,000 points, ranking number three on the arcade’s leaderboard. Not bad.

Then Meier went up. He scored 150,000 points.

“I was really torqued,” Stealey says today. This guy outflew an Air Force pilot? He turned to the programmer. “Sid, how did you do that?”

“Well,” Meier said. “While you were playing, I memorized the algorithms.”

A great video game, Sid Meier likes to say, is a series of interesting decisions: a set of situations in which the player is constantly confronted with meaningful choices. It’s an ethos that has served him well: the majority of Meier’s games are critically and commercially acclaimed. A 2009 Develop survey asked some 9,000 game makers their “ultimate development hero”—Meier came in fifth. (First was Mario creator Shigeru Miyamoto.)

Meier’s games are all full of interesting decisions, and they’re always totally different. There’s the open-world pirate adventure game; the real-time strategy game set during the Battle of Gettysburg; the simulation game about railroad management. Meier’s most recent release, Ace Patrol, is a top-down strategy game in which you maneuver fighter pilots to take down targets across the battlefields of World War I.

And then there’s Civilization.

In a world full of eight-figure budgets and ambitious video game cinematics, the 20-year-old Civilization’s scope is impressive even today. Some games put players in charge of people, cities, or armies; Civilization put them in charge of world history. You’d pick a nation—Americans, Romans, English, and so forth—and guide them from 4000 BC to the modern age, year by year. Every turn, you could move your people across a 2D map of the world, build settlements and cities, engage in diplomacy with rival countries, research new technology, irrigate land, and wage war.

Sid Meier: The Father of Civilization

This formula has spawned five main games, several spinoffs (including the North America-focused Colonization and the sci-fi epic Alpha Centauri), and tons of expansion packs. It’s also made “Sid Meier” a gaming household name: the official title for Civilization is not Civilization; it is Sid Meier’s Civilization. The title implies ownership, arrogance, cockiness. It would be easy to conclude, then, that the father of PC strategy games is a man with an ego—the type of man who would put his name on every game he makes.

But Meier is amiable and soft-spoken, a friendly man who colleagues call brilliant, unassuming, and humble. “In the [13] years and all the people I’ve worked with at Firaxis,” said fellow designer and close confidant Jake Solomon, “there has never been anyone who’s had a personality issue with Sid, ’cause it’s not possible. He’s such a wonderful person.”

Last month, I met the legendary designer in a chilly meeting room in Manhattan’s Union Square. Meier was genial and energetic, with a warm smile and a dark grey cardigan. He was accompanied, as always, by his wife, Susan, who occasionally chimed in to help him remember important facts, or moments he’s forgotten. We talked about his games, his history, his triumphs and regrets.

A devout Christian, Meier loves music and plays organ for his church in Baltimore, Maryland, where he and Susan live. His job title at Firaxis, the studio he helped found, is “Director of Creative Development,” which essentially means he can do whatever he wants. Sometimes that means working on his own games; other times it means offering his considerable design acumen to other people at the company and helping out on projects like XCOM, the sci-fi strategy game helmed by Solomon.

“You can always drop in—his door’s always wide open,” said Solomon. “Anybody can stop in and talk to him about anything… he’s incredibly welcoming. He spends a lot of his time working. If you come in on the weekend, there’s a fair chance that Sid’s car’s in the parking lot, and he’s in the office working on his latest idea.”

Solomon: “If you come in on the weekend, there’s a fair chance that Sid’s car’s in the parking lot, and he’s in the office working on his latest idea.”

I asked Meier, who is 59, if he ever thinks about retirement. “I kinda feel like I am retired,” he said, laughing. “I’m doing what I wanna do—I’ve been retired for a long time. I still love making games, so I’ve really never thought of that.”

That’s good news for video game fans: Meier has a knack for making strategy games that are fiendishly addictive and consistently delightful. He’s fascinated by history, and he is particularly good at turning events that would seem quaint, dull, or old-fashioned to your average game player—like the battle of Gettysburg or a World War I air skirmish—into accessible interactive entertainment.

When I’m in the cockpit of a fighter aircraft, the last thing I want to do is slow down — I certainly don’t want to wait my turn. I need… Read…

“He just is brilliant,” said Solomon. “He has a gift that I certainly don’t have. It’s very rare to find someone who is able to look at the world in such a way that you could give him a topic for a game and I guarantee you in a weekend he could come up with a prototype centered around that theme that would make you go, ‘Oh man, that’s pretty fun.’ Sid just has a very insightful way of looking at the world. He can find the fun in almost anything.”

“He just thinks differently from us,” said Brian Reynolds, a longtime collaborator who designed Civilization II. “It’s an ineffable thing. His smartness doesn’t come off as, ‘I’m smarter than you, haha.’ You just have this really interesting conversation and it starts to dawn on you how much smarter he is.”

“I gave him a [Civil War] book for Christmas one year,” said Stealey. “And at New Years he gave it back to me. I said ‘Sid, didn’t you like the book?’ He said, ‘I’ve memorized it already.’”

After whupping Stealey at Red Baron, the young Meier told his co-worker that Atari’s flight sim was okay, but he could make an even better one. Stealey took the bait: “if you could, I could sell it.”

Meier lived up to his end of the bargain, and a few months later, he brought Stealey a build for a combat flight sim called Hellcat Ace. So Stealey went out and sold it. This was the beginning of a partnership that would last for the next decade: As Meier designed and programmed, Stealey would go out and pitch his games to local hobby stores. After a year of sales—$200,000 worth, Stealey claims—Stealey quit his job at General Instruments to work full-time at the company they were now calling MicroProse. A year and a half later, Meier did too.

Over the next few years, MicroProse made and marketed a number of flight simulators and arcade action games for Atari consoles: games like the World War II flyer Spitfire Ace, the rudimentary platformer Floyd of the Jungle, and the helicopter sidescroller Chopper Rescue. Like many of the earliest video game companies, MicroProse felt like an upstart gang of rebels more than a professional operation.

“We put [the games] in baggies,” Meier said. “Bill would drive around to stores and sell them. It was very bootstrap round-up work process. That’s the way things were.”

“I would call computer stores and ask to buy Hellcat Ace,” Stealey told me. “And when they didn’t have it, I would yell and scream at them, ‘What kind of computer store are you?’ and hang up.

I would do that three times in three weeks, each time pretending to be a different person. And the fourth week I’d call and say, ‘Hello, this is John Stealey. I’m a representative with MicroProse, with this game called Hellcat Ace.’ They’d say, ‘Hey, hey, hey, everyone’s been calling about that, can you help us get that game?’”

Sid Meier: The Father of Civilization

In 1983, a video game crash caused by market saturation crippled companies like Atari and Magnavox, but MicroProse still found success releasing a steady trickle of high-quality games designed by Meier: mostly flight sims, because that’s what the two were interested in making.

A few years later, as the company continued to grow—”It took three years to get to $3 million,” said Stealey—someone suggested that they make a game about pirates. Meier liked the idea, and he recalls one particularly important conversation with Stealey:

“Bill said, ‘When’s my next flight simulator coming out?’ And I said, ‘I’m not doing a flight simulator; I’m doing a pirates game.’ He said, ‘Well that’s crazy, ‘cause people want your next flight simulator… Wait a minute. Put your name on it. Maybe if they liked your flight simulator games, they’ll recognize the name and buy this crazy pirates thing.’”

Stealey has a different take: “We were at dinner at a Software Publishers Association meeting, and [actor] Robin Williams was there. And he kept us in stitches for two hours. And he turns to me and says ‘Bill, you should put Sid’s name on a couple of these boxes, and promote him as the star.’ And that’s how Sid’s name got on Pirates, and Civilization.”

Wherever it came from, the idea stuck. In 1987, MicroProse released Sid Meier’s Pirates!, an open-world exploration game in which players took on the role of glamorous swashbucklers who scour the world for treasure, stave off mutinous crews, and try to earn as much money as possible.

“We had created this graphic tool that allowed us to bring up pictures quickly,” Meier said. “Memory was limited. Everything was limited, so you had to be very efficient, but we found an efficient way to kind of pop up these pictures. We were able to kind of illustrate each scene in the story. That gave it a little bit of this adventure book story kind of quality that I think worked well.”

It worked extremely well: Pirates! won a number of awards from industry shows and magazines, and influenced a great deal of future games, including Will Wright’s SimCity, which would then go on to influence Meier’s Civilization.

Meier recalls early Game Developers Conferences in San Jose, California, where he’d get together with Wright, M.U.L.E. designer Danielle Bunten, conference founder Chris Crawford, and about 50-100 other early game creators.

“We would have fun and basically tell each other how much we like each other’s games,” Meier told me. “There wasn’t really any collaboration, because we just all wanted to make our own games. It was too much fun to let anybody else.”

It was the first generation of video game designers. And it felt like they were at the precipice of something big.

“We were trying to develop an industry,” Meier said.

If you play more than one of Meier’s games, you will notice certain common characteristics: there is never any blood, for one. Although Meier likes to cover violent historical periods, he does not like to show violence: battles in Civilization, for example, are represented abstractly, with two army tiles colliding until one disappears.

Meier’s games are also known for giving their players all sorts of options: instead of telling a focused, linear story, Meier prefers to create situations in which the player can create his or her own narrative. It could be the story of America wiping out every other nation and creating a global empire, or it could be the story of the most friendly pirate in the Caribbean. It’s totally up to the player. “I prefer games where the player can lead the game in the direction that they want,” Meier said. “And then they kind of end up with that unique story that only they can know.”

Meier: “I prefer games where the player can lead the game in the direction that they want, and then they kind of end up with that unique story that only they can know.”

No game epitomized this principle more than Civilization, which Meier and his team started developing after Pirates! and their next game, a business sim called Railroad Tycoon in which players could built and manage their own railroad companies.

“[SimCity] planted the seed in our mind about this kind of building, and that games don’t have to be about blowing things up—they can be about creating,” Meier said. “And so we kind of took some of the ideas from Railroad Tycoon, and some of the ideas from SimCity, and said you know what’s a bigger topic that we can tackle? And we ended up with the idea of Civilization.”

Today, it takes two or three years and a team of at least 100 to make your average blockbuster video game. Civilization, Meier told me, was made by a team of 8-10 people in under a year.

“Ultimately we had 640 kilobytes [of memory] in the computer,” Meier said. “When that was full, we were done. We couldn’t put any more code in there. So development time was a little less in those days.”

Today, Civilization is known as one of the premier turn-based strategy series, but funny enough, one of the game’s first iterations was actually set in real-time, like StarCraft or Age of Empires.

The unreleased prototype just didn’t pass muster with Meier.

“It was more like SimCity, where you’d kind of say, I wanna have a village over here and a farm over here and maybe I want to have some things happening over here, and then you could kind of stand back and watch your people gradually do things,” Meier said. “But it was a much more passive kind of process. There was more watching than doing. It was just not happening.”

So they switched gears. They gave more control to the player and changed up the pacing: now, instead of waiting for the world to change, players could change the world. Time wouldn’t progress until players made their decisions.

Brian Reynolds, who at the time had just started working at MicroProse, remembers early builds of Civilization keeping him and his co-workers up all night.

“It started to kind of go ‘viral’ within the company—not that anybody knew that term back then,” Reynolds said. “It was one of those things that suddenly everybody was kind of playing it.

There’d be a new version every few days. I would go in and just be this random 22-year-old guy stopping by and saying, ‘Here’s some ideas!’ [Sid] was very tolerant, patient of all my ideas for Civilization.”

“It was a very fun development,” said Meier, who was in his late 30s at the time. He remembers scaling down a lot—the game’s map was originally going to be twice the size, and there were two different types of tech trees—and he recalls lots and lots of play-testing alongside assistant director Bruce Shelley.

“Testing was a bit of a challenge because it took so long to play the game,” Meier said. “And we didn’t really have much in the way of testers, so I was one of the main—a lot of my time was spent playing and then fixing and changing.”

Civilization came out in late 1991. It took a few months for buzz to build—there was no Internet just yet—but as people started to discover the game, it spread like the Romans. Meier’s masterpiece won various awards, ranking #1 on a list of “150 Best Games Of All Time” compiled by the magazine Computer Gaming World. And it sold 800,000 copies, according to Reynolds.

Sid Meier: The Father of Civilization

When Meier finished the game that would make his career, he was eager to make something bigger. Better. More ambitious. But he also knew that would be ridiculously difficult—“I said if I continually get in this mode of trying to top the last game or do something bigger or more epic, I’m gonna drive myself crazy,” Meier said. So he decided to scale back. He gave Reynolds the steering wheel for the U.S.-focused Colonization and the Civ sequel, then went off to do his own thing: a music application called CPU Bach that allowed players to create their own music compositions. (It never really took off.)

Meanwhile, MicroProse was facing corporate restructuring as Stealey attempted to balance the company’s budget. In 1993, Stealey sold MicroProse to a company called Spectrum Holobyte. A year later, he left. “It was a great run. We should’ve done better. We had great people,” Stealey said. “I think all our people are still very proud of their MicroProse days. We had a family atmosphere. We had cash bonuses for everybody. I think it went very well for a long time.”

Sick of the layoffs and corporate politics, Meier—along with Reynolds and fellow designer Jeff Briggs—decided to leave MicroProse and start a new company. They called it Firaxis Games.

Sid Meier doesn’t like thinking about business, and he clammed up a bit when I asked him about MicroProse’s new ownership. “Sid didn’t want to be involved in that at all,” Stealey told me later. “No business—not at all.”

“Sid is happiest in his office writing code,” Solomon said.

Perhaps that was what made the idea of Firaxis so exciting for Meier: there they were independent, totally free to make creative decisions without worrying about meddling corporate parents. By then, Meier already had a reputation in the booming video game industry, and the company was quickly able to strike a deal with Electronic Arts for their next couple of games: Alpha Centauri, a Civilization spinoff set on an alien planet, and Gettysburg, a real-time strategy game set during the eponymous Civil War battle.

“Ah, Firaxis,” Meier said. “The convicts are running the asylum. It was great fun.”

For a while the company stayed small and nimble, making games with a team of 10-15 people, but over the past decade and a half, it’s grown closer to 120. In late 2005, Firaxis was acquired by Take-Two Interactive—the publishing company behind Rockstar (Grand Theft Auto) and 2K (NBA 2K).

Meier: “Ah, Firaxis. The convicts are running the asylum. It was great fun.”

“Everyone here is really nice,” said Solomon, who joined Firaxis in 2000. “We really value nice guys and gals. We don’t really put up with personality conflicts here, and that comes from Sid.

That is 100% because our studio grew out of Sid Meier, and his personality has a huge impact on how the studio is run, how people interact with each other. His vision is sort of our company vision.”

Over the past decade or so, Firaxis has gone on to make a whole bunch of Civilization sequels and spinoffs, including the console-driven Civilization Revolution and a remake of Colonization. Last year’s reimagining of the sci-fi strategy game XCOM (directed by Solomon) earned tons of critical acclaim, winning Kotaku’s 2012 Game of the Year. And now, with Ace Patrol, the ghoulish Haunted Hollow and an iOS port of XCOM, the studio seems to be diversifying a bit more.

The staff of Kotaku nominated nine games for 2012 Game of the Year. One game, XCOM: Enemy Unknown, blew the competition away. Read…

X-COM Makers’ Mobile Monster Mash Conquers Hearts And Wallets Alike

There’s quite a lot of extra content available for purchase in Haunted Hollow, the spooky new iOS strategy board game from Firaxis, creators of… Read…

Ahab had Moby Dick. Sid Meier has dinosaurs.

For the past decade-and-a-half, Meier has unsuccessfully tried to spear a tyrannosaurus rex. He’s always wanted to make a game about the Jurassic and Cretaceous periods—”Sid Meier’s Dinosaurs” does have a nice ring to it—but he just couldn’t figure out how to make it fun. The theme worked, but he never found the right gameplay foundation: what would the dinosaurs do? Just fight one another? What’s the progression?

“I did three different prototypes,” Meier said. “One was real-time, one was turn-based, and one was a card game. And they were all kind of fun but just not fun fun.”

“How can you tell?” I asked.

I’d heard that Shigeru Miyamoto was really proud of his new game, Pikmin 3. Like, really, really proud. Like,… Read…

“I play the game,” he said, sounding very much like one of his legendary counterparts, Mario creator Shigeru Miyamoto. “That’s how I develop it, by playing the game, tweaking it and changing it.

If other people play it, and they’re like ‘Oh, that’s okay,’ I ask, ‘But you’re still not playing it?’ If they say, ‘No, I put it away’ then I know it’s a problem. If they’re still not playing it, then it’s not as fun as it needs to be.”

Meier’s wife, Susan, chimed in. Susan has been with Firaxis since the beginning, first as the head of human resources, and now as “Master of Miscellaneous,” as she likes to call herself. “One of the reasons you knew you had something was that people at work were playing it long and often,” she said.

“Even when they didn’t have to,” Meier said, laughing. “That’s a good sign.”

Meier: “If other people play it, and they’re like ‘Oh, that’s okay,’ I ask, ‘But you’re still not playing it?’ If they say, ‘No, I put it away’ then I know it’s a problem. If they’re still not playing it, then it’s not as fun as it needs to be.”

But he just couldn’t nail down the dinosaurs. Solomon, meeting with Meier for the first time while interviewing for a job at Firaxis, recalls sitting down with the designer and playing one of his dinosaur prototypes.

“He fired it up and he let me play,” Solomon said. “I think he basically just looked at this as an opportunity to get feedback from somebody. I played the game and we talked about the game… and all he was interested in was, what do I think of the game? Did I have fun? What would I change? And it wasn’t an interview in the sense of—well, I suppose he might have been using it to gauge my personality—but really, it was an interview in the sense of, I played an awesome little prototype of Sid Meier.”

Solomon couldn’t make the game great, though. Meier likes to talk about the “valley of despair”—the moment in which a game designer, crushed by the weight of failed ideas and discarded prototypes, just feels like giving up. (“Sid’s famous for saying a game is a series of interesting decisions,” Solomon told me. “On Civ Rev one time he cracked and said, ‘Playing games is a series of interesting decisions, but making games is a series of heartbreaking disappointments.’”)

Sometimes, they get out of the valley. Other times it can be smothering.

Not long after Solomon joined the company, Meier told everyone that he was finished. He couldn’t make the dinosaur game work.

“So he goes home, and we don’t see him for two weeks,” Solomon said. “Then he brings everybody into a little room and he’s like ‘Okay, I’ve got the next game.’ And so he puts it up on the screen, and it’s SimGolf.”

It wasn’t a video or a bunch of words about SimGolf: it was a working prototype that Meier had just built. Players could design and build basic golf courses, just like they eventually could in the final product.

“At that time, [then-EA exec] Bing Gordon came out and went into Sid’s office, sat down, played the game for maybe an hour or two, came out and said ‘Yep, we’ll be able to sell that!’”

Solomon told me. “Anyone who saw it saw that it was pretty awesome.”

Sid Meier: The Father of Civilization

That prototype-centric mentality is how Meier has always made games, and it may be one of the explanations for his success: he doesn’t believe in design documents, or long, written descriptions of how a video game will work. While many game makers put ideas and concepts on paper before taking them to a machine, Meier’s approach is all hands-on.

“Sid’s never had to write a design document, because instead of debating with you about some new feature he wants to implement, he’ll just go home and at night he’ll implement it,” Solomon said. “And then tomorrow when he comes in he’ll say, ‘Okay, now play this new feature.’ And you’ll play, and then you can have a real conversation about the game, instead of looking at some design document.”

Meier is known for these types of rules and mantras, which he likes to share with other game designers as often as possible.

“‘Find the fun’—that’s Sid’s phrase,” said Reynolds. “Essentially, you have to make something in order to have any chance of finding the fun. Fun wasn’t going to be found on a piece of paper, at least fun in terms of a video game.”

To hear Reynolds describe Meier’s process calls to mind the old joke: “How do you carve a statue of an elephant? Get a block of marble and remove anything that doesn’t look like an elephant.”

How do you make a good game? Get a game and remove all the parts that aren’t fun.

“He told me a phrase I use all the time,” said Solomon. “Feedback is fact. That’s the way you have to look at feedback, as if it’s a fact. You’ve worked on this massive system or this game, and they come in your office and they go, ‘I played it, and I was bored.’ The worst thing you could do as a designer is start to defend your design or argue with that person. What you do is accept what that person told you as a fact. They said they were bored, so guess what? Your game bored that person. And you need to figure out why that is.”

There are other rules, too. Reynolds recalled one that stuck with him: if you are making a video game, and you’re having trouble with a number—say, the number of damage points a unit can do—either double it or cut it in half.

“He didn’t have any patience for, ‘Let’s try increasing it by 10%. Let’s try another 10%,’” Reynolds said. “Turns out that’s a pretty good rule of thumb to start with for a game designer, because the typical thing is to be really careful and try to inch up a little bit, and then you have to change it seven times to get it right. If you double it, you’ll immediately feel whether making it stronger was even a good idea.”

Meier: “I guess the next question is, ‘What would you do to try to make the game less fun?’”

The process works. Meier’s games are undoubtedly excellent, to the point where gamers often tell stories about them: “I started playing Civilization at 8pm and then suddenly it was four in the morning” is a common one. The word “addictive” is often thrown around—always with positive connotations, yes, but addiction can be a dangerous thing.

So I was curious, during a chat with Meier. Does he ever worry that his games could have a harmful effect on peoples’ lives?

“The responses we get on the forums, and interacting with players, and talking to people… our impression is that it’s a positive experience. It’s a way of using your leisure time that might otherwise be spent watching television or whatever. It’s a leisure time choice. So our reaction from players has been positive in terms of the time they spent, what they thought they got out of it, how they exercise their brains, and learn things about the world.

“I guess the next question is, ‘What would you do to try to make the game less fun?’ It’s funny—in some of the very early PC game designs, we used to have this ‘boss key,’ which you’d—you’d kinda hit a special key, and a spreadsheet would pop up on the screen so you could pretend you were doing your job. So I guess it’s been a consideration going back even 10 or 20 years. Games are just fun.

“It’s up, with any form of entertainment, it’s up to the player or parents to decide what’s appropriate and what’s not appropriate. Our goal is to make the games as fun as we can make them. I think that seems to be what most people are looking for.”

Civilization doesn’t have slaves, and some have criticized the game for that glaring historical omission. It’s a common trend in Meier’s works: although they cover history, they tend to omit the nastier parts. That’s just how Sid Meier makes games. It’s been that way from Civilization to SimGolf to any of the games he’s worked on in the two decades since.

“There’s a conflict between an emotionally-charged topic and kinda giving the player this freedom of choice that really makes the game good,” he said. “One of the things we really try to avoid in our games is this kind of—’this choice would be the right thing to do, but this choice is gonna help me win the game’—put the players in those kind of moral dilemmas. That’s not what our games are about. We want you to feel good about yourself when you finish the game.”

A feel-good, addictive experience with tons of interesting choices: that has become the definition of a “Sid Meier” game. Maybe that’s why they put his name on the box. There’s certainly value to video games that tell focused, morally-challenging stories—last year’s Spec Ops: The Line (published by 2K, the label behind Firaxis’s games) was lauded for just that reason—but Meier doesn’t want to make games like that. He wants to make the type of games that he wants to play.

Yet… to this day, Meier has yet to create a game as memorable or as significant as Civilization. After SimGolf was a remake of Pirates!, and then Meier designed the fourth Railroad Tycoon game, Railroads! Next was the console-friendly Civilization Revolutions, a Facebook game called CivWorld that shut down earlier this year, and Ace Patrol. All of these games, while generally good, have not stuck with people the way his magnum opus has. And although Meier told me he has no regrets—”Except that I didn’t think of Tetris.”—I imagine he must sometimes feel like Civilization is lording over him, daring him to make something with as much of an impact.

“When we made Civilization, it was not with the idea that this was gonna be the greatest game that we’re gonna be remembered by,” Meier said. “It was the best game to make at the time and we thought it was a lot of fun. Each game we make, we kinda go into it with that idea: this is gonna be the best game we can make on that topic. Some of them resonate stronger with game players; maybe some not as much. I don’t have a formula for making a super-memorable game. It’s just that we keep making the best games that we can.”

篇目2,The Sid Meier Advantage

By John Gaudiosi

The Civ designer talks about the advantage of being a veteran game maker and understanding gameplay as a psychological experience

Sid Meier has been making games for nearly three decades. The legendary game designer continues to evolve the strategy game genre with the Civilization V expansion pack, Gods & Kings. Meier’s E3 was busy with two new Firaxis Games titles, the aforementioned Civ V expansion and the new XCOM: Enemy Unknown, a re-imagining of the classic 1993 turn-based strategy game.

Considered by many to be the “Father of Computer Gaming” from his MicroProse Software days, Meier remains entrenched in game development every day as director of creative development at Firaxis. The man behind hits like Railroad Tycoon, Sid Meier’s Pirates! and Sid Meier’s Gettysburg took a break to talk about the current game industry in this exclusive interview.

Q: What are your thoughts on how far the game industry has grown since you entered the business?

Sid Meier: I always felt that there was a great opportunity for growth as we figured out how to make games better and we’re seeing a larger audience today than ever before with social and mobile gaming and the gamification of everything. It’s something that I actually thought would happen over time. We would start off with our core audience and strategy gaming, but as we figured out how to make games more accessible and reach a wider audience, it would grow.

The challenge with this kind of growth is to keep these new gamers interested in games and sustain this momentum. We need to keep them coming back to new games and fresh ideas. Time will tell whether this growth is one cycle in the industry or if it is something that is permanent.

Q: What are the advantages of being a veteran game developer?

Sid Meier: Having worked on older games that had crude graphics, older designers like me actually have an advantage over younger designers because we have worked hard to make people believe things despite the graphics. Part of the unholy alliance is that you need to create a suspension of disbelief. It’s your part of the bargain, and it’s the gamers’ part, too.

Q: When you look at the game industry today what surprises you?

Sid Meier: I’m constantly surprised by the technology innovation that gets better and better, but on the other hand we always expect the industry to evolve and introduce new things. That’s the part that keeps it fun and really interesting for us.

Q: What impact do you feel Kickstarter will have on the game industry?

Sid Meier: That’s certainly a new opportunity to add to the App store, Xbox Live Arcade, PlayStation Network and all those places where the more reasonably sized games can find an outlet. If you can pull it off, then that’s a great opportunity. I think we’ve certainly seen in the last couple of months some successes there. If you have something that is really compelling in terms of a story idea then that is a very interesting way to go.

Q: What keeps you excited about coming to work every day at Firaxis?

Sid Meier: I really enjoy making games, it’s just fun. It’s like taking a lumpy piece of clay and turning it into something very cool. Every day is part of that process. Not knowing exactly where we are going and figuring it out step by step is just a challenge. It’s almost like the “one more turn” phenomenon in Civilization. It’s looking to that next thing we are going to add to the game and seeing how we can just make it better. The fun for me is really not knowing from week to week what cool thing we are going to add and getting a chance to play with it and tweak it and the constant process of seeing a game grow before your eyes.

Q: Where do you see the game industry five years from now?

Sid Meier: I imagine we’ll have different technologies to go through a cycle where they’re brand new and you’re experimenting with a lot of different ways of using this technology. That happened with the CD-Rom, with multiplayer on the Internet, and it’s now happening in the early stages with social gaming and mobile gaming. In five years we’ll have social gaming figured out with different genres. We’ll have different kinds of social games and everyone will understand the rules and the interface. Mobile is probably a technology we haven’t gotten the most out of.

Q: So where do you see opportunities for mobile games?

Sid Meier: Mobile games now are five minute quick gaming fixes. When you look at all the technology in a smartphone, the connectivity, the GPS, the camera, there are all sorts of things that could be integrated into a gaming experience that we haven’t thought of yet. I have a feeling that we will start to explore more of what’s possible in the whole space. Who knows what the technology will be. The iPad is a beautiful piece of hardware that does really cool stuff. We’re still trying to catch up in terms of game design and how to take advantage of it.

Q: What do you think is the key to a successful game?

Sid Meier: One of the key rules of game design is the first 15 minutes. These introductory minutes have to be fun, satisfying, and exciting. You are letting players know they’re on the right track, you should reward them, and let them know cool stuff will happen later.

In early Civilization games, I made Civ real-time, which meant everything happened in real-time: My first mistake was to make it real time. I modeled some elements of the game from SimCity, which was real-time. It was inspiring. But what we found was that in real-time gaming the player becomes the observer. Our mantra is that, “it’s good to be king.” When we made Civ a turn-based game, the player became the star, they made things happen.

Q: What’ something you’ve learned about game development that has remained true over the years?

Sid Meier: Gaming is a psychological experience. I base my games on things like railroads, pirates, and history, and I try to make the games I design true and real. The more historical, the more realistic, and the more factual, the better. During the early days of my career, I hadn’t taken into account what was in the player’s head. By acknowledging that simple concept-that gameplay is a psychological experience-it can make your games better.

Q: What impact has the influx of new gamers coming to the space from Facebook and mobile devices had on game development?

Sid Meier: I once gave a talk on how games should be split into four different difficulty levels. I was wrong. Now, Civilization V has nine difficulty levels. As players move on they continually get better and receive rewards. You want to feel they are above average. There is a basic dichotomy in games in that when you reward players for winning a war and give them 100 gold pieces, the player never really questions rewards. If something bad happens, if there is a setback to the player, they react much differently. They complain the game is broken.

Q: What role will PCs play in the future of games?

Sid Meier: If history is any guide, then PC will just continue to be a strong platform for gaming. We’ll see a new generation or two of consoles. Maybe your watch might play a game, I don’t know. I think gaming will continue to go wherever technology goes. It’ll be a fun five years.

篇目3,Analysis: Sid Meier’s Key Design Lessons

By Soren Johnson

Most game developers are familiar with Sid Meier’s dictum that “a good game is a series of interesting choices.”

In fact, my co-columnist Damion Schubert started his recent article on player choice (October 2008) by referencing this famous quote.

However, over the course of his career, Sid has developed a few other general rules of game design, which I heard him discuss many times during my seven years (2000-2007) at his studio, Firaxis Games. As these insights are quite practical lessons for designers, they are also worthy of discussion.

Double It Or Cut It By Half

Good games can rarely be created in a vacuum, which is why many designers advocate an iterative design process, during which a simple prototype of the game is built very early and then iterated on repeatedly until the game becomes a shippable product.

Sid called this process “finding the fun,” and the probability of success is often directly related to the number of times a team can turn the crank on the loop of developing an idea, play-testing the results, and then adjusting based on feedback.

As the number of times a team can go through this cycle is finite, developers should not waste time with small changes. Instead, when making gameplay adjustments, developers should aim for significant changes that will provoke a tangible response.

If a unit seems too weak, don’t lower its cost by 5%; instead, double its strength. If players feel overwhelmed by too many upgrades, try removing half of them. In the original Civilization, the gameplay kept slowing down to a painful crawl, which Sid solved by shrinking the map in half. The point is not that the new values are likely to be correct – the goal is to stake out more design territory with each successive iteration.

Imagine the design space of a new game to be an undiscovered world. The designers may have a vague notion of what exists beyond the horizon, but without experimentation and testing, these assumptions remain purely theoretically. Thus, each radical change opens up a new piece of land for the team to consider before settling down for the final product.

One Good Game Is Better Than Two Great Ones

Sid liked to call this one the “Covert Action Rule,” a reference to a not-altogether-successful spy game he made in the early ’90s:

The mistake I made was actually having two games competing with each other. There was an action game where you break into a building and do all sorts of picking up clues and things like that, and then there was the story which involved a plot where you had to figure out who the mastermind was and what cities they were in, and it was an involved mystery-type plot.

Individually, each part could have been a good game. Together, they fought with each other. You would have this mystery that you were trying to solve, then you would be facing this action sequence, and you’d do this cool action thing, and you’d get out of the building, and you’d say, “What was the mystery I was trying to solve?” Covert Action integrated a story and action poorly because the action was actually too intense – you’d spend ten minutes or so of real time in a mission, and by the time you got out, you had no idea of what was going on in the world.

In other words, even though both sections of the game were fun on their own, their co-existence ruined the experience because the player could not focus her attention on one or the other.

This rule points to a larger issue, which is that all design choices only have value in relation to one another, each coming with their own set of cost/benefit trade-offs. Choosing to make a strategic game also means choosing not to make a tactical one. Thus, an idea may be “fun” on its own but still not make the game better if it distracts the player from the target experience. Indeed, this rule is clearly the reason why the Civ franchise has never dabbled with in-depth, tactical battles every time combat occurs.

However, sometimes multiple games can co-exist in harmony with each other. Sid’s own Pirates! is an example of a successful game built out of a collection of fighting, sailing, and dancing mini-games. However, these experiences were always very short – a few minutes at the most – leaving the primary focus on the meta-game of role-playing a pirate. Each short challenge was a tiny step along a more important larger path, of plundering all Spanish cities or rescuing your long-lost relatives.

Another example of a successful mix of separate sub-games is X-Com, which combined a tactical, turn-based, squad-level combat game with a strategic, real-time, resource-management game. As with Pirates!, what makes X-Com work is that the game chose a focus – in this case, the compelling tactical battles between your marines and the invading aliens.

The high-level, strategic meta-game exists only to provide a loose framework in which these battles – which could take as long as a half hour each – actually matter. One doesn’t fight the aliens to get to manage resources later; instead, one manages resources to get to perform better – and have more fun – in future battles.

Do Your Research After The Game Is Done

Many of the most successful games of all time – SimCity, Grand Theft Auto, Civilization, Rollercoaster Tycoon, The Sims – have real-world themes, which broadens their potential audience by building the gameplay around concepts familiar to everyone.

However, creating a game about a real topic can lead to a natural but dangerous tendency to cram the product full of bits of trivia and obscure knowledge to show off the amount of research the designer has done. This tendency spoils the very reason why real-world themes are so valuable – that players come to the game with all the knowledge they already need.

Everybody knows that gunpowder is good for a strong military, that police stations reduce crime, and that carjacking is very illegal. As Sid puts it, “the player shouldn’t have to read the same books the designer has read in order to be able to play.”

Games still have great potential to educate, just not in the ways that many educators expect. While designers should still be careful not to include anything factually incorrect, the value of an interactive experience is the interplay of simple concepts, not the inclusion of numerous facts and figures.

Many remember that the world’s earliest civilizations sprang up along river valleys — the Nile, the Tigris/Euphrates, the Indus — but nothing gets that concept across as effectively as a few simple rules in Civilization governing which tiles produce the most food during the early stages of agriculture. Furthermore, once the core work is done, research can be a very valuable way to flesh out a game’s depth, perhaps with historical scenarios, flavor text, or graphical details. Just remember that learning a new game is an intimidating experience, so don’t throw away the advantages of an approachable topic by expecting the player to already know all the details when the game starts.

The Player Should Have The Fun, Not The Designer Or The Computer

Creating story-based games can be an intoxicating experience for designers, many of whom go overboard with turgid back stories full of proper nouns, rarely-used consonants, and apostrophes. Furthermore, games based on complex, detailed simulations can be especially opaque if the mysterious inner workings of the algorithmic model remain hidden from view. As Sid liked to say, with these games, either the designer or the computer was the one having the fun, not the player.

For example, during the development of Civilization 4, we experimented with government types that gave significant productivity bonuses but also took away the player’s ability to pick which technologies were researched, what buildings were constructed, and which units were trained, relying instead on a hidden, internal model to simulate what the county’s people would choose on their own.

The algorithms were, of course, very fun to construct and interesting to discuss outside of the game. The players, however, felt left behind — the computer was having all the fun — so we cut the feature.

Further, games require not just meaningful choices but also meaningful communication to feel right. Giving players decisions that have consequence but which they cannot understand is no fun. Role-playing games commonly fail at making this connection, such as when players are required to choose classes or skills when “rolling” a character before experiencing even a few seconds of genuine gameplay.

How are players supposed to decide between being a Barbarian, a Fighter, or a Paladin before understanding how combat actually works and how each attribute performs in practice? Choice is only interesting when it is both impactful and informed.

Thus, in Sid’s words, the player must “always be the star.” As designers, we need to be the player’s greatest advocate during a game’s development, always considering carefully how design decisions affect both the player’s agency in the world and his understanding of the underlying mechanics.

篇目4,GDC 2012: Sid Meier on how to see games as sets of interesting decisions

by Leigh Alexander

“Games are a series of interesting decisions,” says Firaxis’ Sid Meier. It’s a statement he’s made in the past – and he’s noticed (by Googling himself) that viewpoint of his has been a source of some debate. But it’s one of his favorite ways of thinking about game design, so in his packed GDC 2012 lecture, he explained the idea in depth – what makes decisions in gameplay interesting for players, and what do designers need to know?

“It’s easier to look at it as what is not an interesting decision,” says the legendary creator of Civilization. If a player always chooses the first from among a set of three choices, it’s probably not an interesting choice; nor is a random selection. While there are some types of games where the idea of interesting decisions isn’t the best way to look at things – say rhythm games or puzzle games based on different sorts of inputs — he generally believes the idea is a helpful way to look at the medium.

“It’s a useful concept during the design phase. One of the things I see often is that designs are kind of about putting together pieces of other games,” says Meier. There’s the idea that if some games are fun, then combinations of their elements will also be fun.

“Unfortunately, that doesn’t always work out,” he says. “And I think it’s a more useful way to look at a new game design in terms of, what are the decisions I’m presenting the player, and are they interesting?… Put yourself in the player’s chair.”

What Makes An Interesting Decision?

One common characteristic of interesting decisions is that they involve some kind of tradeoff – say, the opportunity to get a big sword costs 500 gold, or in a racing game the fastest car may have poorer handling. In Meier’s Civilization, the act of building a defensive unit has complex resource costs in exchange for protection.

“Good decisions are situational. There’s a very key idea that when the decision is presented to the player, ideally it acts in an interesting way with the game situation,” Meier explains. Civ contains complex systems that provide a number of situational choices, where the options presented to players and the factors therein depend heavily on what’s happening in the game world.

Some of these decisions are personal and tied to the player’s gaming style. A cautious player would choose to build a very secure base from which to expand; an aggressive player invests in its offensive units. “This interesting decision would allow you to express your personal play style,” he says.

Interesting decisions are persistent and affect the game for a certain amount of time, as long as the player has enough information to make the decision – when early choices can ruin the game experience down the road, developers need to present them in a fashion appropriate to that. “

One classic decision type is a risk-versus-reward scenario that asks the player to weigh potential penalties against the possibilities of rewards. “In almost any kind of game you’ll find opportunities for these decisions,” he says. Another decision category is short versus long-term decisions – like building a wonder in Civilization, which takes a long time but has a significant long-term impact – versus building a chariot, which is finished much more quickly but has much less effect on the overall landscape of the game.

When it comes to accommodating the player’s play style, “it’s very tempting as a designer to imagine that everybody plays a game the same way that you do, and it’s very tempting as a design and development group to feel that you represent all players,” he says. That’s why he finds it essential to good design to allow for as many choices and play styles as possible.

One of the strengths of Civilization in Meier’s own view, is that it has things happening on multiple levels at once in terms of short-, medium- and long-term events. The player’s task is to prioritize and to manage strategies for both near-term and long-term goals, and evolve the short-term goals to make the long-term goal more accessible.

Customization functions also create interesting decisions, even if it’s as simple as choosing a name for your city or a color for your vehicle. “It makes [the player] more connected to the game that they’re playing,” Meier says. “Think about ways of investing the player in your game by inviting them to make decisions that let them to express their personality or their gaming style.

Informed Choices

Key to making decision meaningful is to ensure players understand the full scope of their choices; it’s not fun for the player to be in a situation where they have to pick something, and then marinate in that gnawing feeling of wondering what might happen as a result of their choice or how severe the impact might be. “It’s almost worth erring on the side of providing the player with too much information, or at least enough that they’re comfortable with understanding the choices,” Meier advises.

When it comes to making players comfortable and happy as they make decisions, genre conventions help – the fact that most shooters have something of a standard interface help players feel assured. When a player presses a button that in every other game in its genre does a certain thing and receives an unfamiliar result, “there’s nothing more disconcerting,” he warns.

One reason that many of Firaxis’ games involve historical topics is that the player can come to the experience with a lot of information that they already know. “It’s important to reinforce that information for the player – if you run into Genghis Khan in a Civilization game, you’re going to expect him to be kinda angry and aggressive… if you’re building a game about railroads or pirates, there’s a lot that the player can bring to a topic like that that they already know.”

Zombies are popular because they’re very clear – their motivation is basic and their nature is obvious and well understood. “It’s an example of a decision where you don’t have to add a lot of information for the player; they pretty much know what to do.”

On the other hand, once the player makes a decision the response from the game is enormously important: “The worst thing you can do is just move on. There’s nothing more paranoia-inducing than having made a decision and the game just kind of goes on. At least have a sound effect that says, ‘I’ve heard what you said and I’m going to do it.’” In Civilization Revolution, players were so pleased to get feedback on some of their unit moves when they negotiated with leaders from other areas, for example.

Feedback helps players feel responsible and meaningful within the game world. “It’s really important to let the player know that you know that they’re there, that you’re a partner with them, that you’re right there next to them all the way,” Meier explains. “That yes, ‘you are the leader of a great civilization’, or ‘you are a great race car driver’. Whether it’s a sound or text, a visual or graphic… really reinforce the fantasy the player is creating in their mind and really allow them to enjoy that.”

The Player Types

In order to create lots of interesting decisions for players, it’s important for designers to understand the many types of players there are. There’s the player that cares mainly about winning, who can offer feedback on tuning the game’s higher levels. There’s the genre fan, who is a fan of the specific genre and loves anything that resembles things they love already – and resents deviations. This player’s feedback is useful for understanding how to use the genre conventions, but hopefully doesn’t constrain new developments.

There’s the player the one who wants to understand all of the game’s algorithm and calculate the best possible scenarios. This player can help with game balance – within reason, as the player really just wants to unravel and own the systems. Then, there’s the paranoid player, who feels that everything is stacked against him or her, assuming that dice rolls are rigged or unfair. The history buff will criticize elements of the setting and complain about loyalty to source material or accuracy of a historical setting.

The player who Meier calls “Mr. Bubble Boy” is the one who dwells on the one unfortunate game experience he or she had. “You need to prevent setbacks in a very sensitive way, where the player understands why it’s happening and what they can do next time… one incident colors their entire experience.” And there’ll always be that armchair designer who focuses on every detail of why a given game isn’t like the one he or she creates.