万字长文,从不同的维度谈游戏的故事设定和意义,中篇

篇目1,万字长文,从三个故事架构层面解析游戏设计

作者:Richard Terrell

以电子游戏和其他媒介中的故事构建来作为文章的开篇似乎很奇怪。但是,请相信我,故事可能是我们理解这个世界和相互理解的最为重要的工具。我获得了英语相关学位,并且 专注于创意写作,所以故事设计是我研究的领域。许多年来,我听过许多人谈论起他们对故事的理解以及故事各个部分所起的作用,但是他们的想法与现实情况偏差甚远。在讨论 何谓故事之前,先明白故事的各个部分是很有益的。

为构建起文学评论理论和游戏设计之间的桥梁,我开设了博客Critical-Gaming。我发觉,利用某些我们较为熟悉的东西(游戏邦注:比如说故事),我们可以更容易地理解游戏设 计。通过博客,我创造和定义了许多的术语,解释了为何像“优秀”之类的描述完全不准确而且起不到任何作用。我的想法在于剖析游戏设计的每个方面,这样我们就能够更清楚 哪些做法能够深化游戏设计,反过来也能让我们明白为何我们会喜欢或者不喜欢游戏的某个方面。我觉得这是种很棒的方法。所以,是时候将这种方法运用于故事中了。

下文将剖析和比较所有类型的故事。虽然我以前提过某些建设性的基本游戏设计理论,但是我相信故事设计要简单得多。我们对故事构建的直觉应该会超出以下观点。如果要理解 故事,我们必须先理解三个主要元素:内容、执行和讲述。

内容

故事就是许多事件的集合。在我们探讨更深层次的含义或执行之前,我们必须关注基本细节或内容。

场景。故事发生的地点。场景由宇宙万物、世界、国家、城镇和时间构成。

角色。维基百科对角色的解释是:叙述性或戏剧性艺术作品中所呈现的人物。角色有各种各样的形式。现实主义并非最佳的角色呈现类型。更为重要的反倒是角色能够以与故事相 关或对故事有用的方式呈现。

情节。维基百科对情节的解释是:用于描述组成故事的事件的文学术语,这些事件可能以某种样式相互联系,比如存在因果关系或一致关系。动作和冲突是情节中的两大类别。

复杂性/简单性。细节产生复杂的故事。有些故事有着丰富的角色、地点和阐述所有内容的背景故事。有些故事这些元素中的某些方面格外出众。

主题。普遍或抽象想法、信息或道德。中心思想(游戏邦注:不断出现的象征性元素)能够使主题得到发展。

执行

故事不仅仅是细节的集合体。无论采用线性或非线性的形式,事件呈现的方式就是故事讲述或执行。如果执行过于缓慢、过于明显、过于混乱或过快,即便最棒的故事内容也不会 产生好的结果。

效能。花较少的精力实现较大的效果。用较少的场景、对话、地点、动作、事件来传播更多的故事内容。情节重复较少便是有效的故事讲述方式。

条理性。可以采用极为简单和直观的故事呈现方式,风格故事并将其重新安排会让故事很难以理解。因为故事讲述是呈现叙事性事件的过程,事件发生的顺序和传播的方式决定了 故事的条理性。

步调。短诗歌有情感波动点。短故事通常也有阐述、动作、高潮和结局等小波段。电视剧、小说和其他长篇故事通常包含有数个“波段”。简单地说,步调就是这些波段来去的快 速程度以及对剧情的影响程度。

风格/语言。这里所说的最为明显的想法是像英语或日语之类的口头语言。但是,语言还包括会话短语、专业词汇、肢体语言、文化标志、冷笑话以及其他修饰性语言。风格的分类 很广,包括所有你认为能够对故事讲述有益的信息传播方式。

媒介。每种媒介都有利有弊。所以,每种媒介都根据自己的优势形成特别的故事讲述方法。尽管这些方法在每种媒介中都能发挥很棒的效果,它们却无法在其他媒介中起到同等作 用。

诗歌最著名的是其浓缩性的文字,其中每个标点符号、文字和格式都有其作用。韵律和结构能够创造出分层化的对比和并列。

短故事擅长于呈现亮点和叙事片段。通过对某些关键时刻的选择,可以在相对紧凑的篇幅中传达出丰富的故事波段。

小说是充满许多细节的大型作品。因为有着这么多的文字,小说可以达到诗歌和某些短故事无法实现的高度。小说中的传播会更加直接。通常来说,书写的语言善于勾起人的内省 ,因为阅读文字可以引发内心的思考。

图片小说、漫画和连环画使用图片的结合来传递信息,并用大量的文字来弥补图片的短处。此类媒介总是能够平衡通过图片呈现和文字讲述的信息。

戏剧和音乐剧使用大量的对话和舞台表演。富有表现力的可视故事讲述很重要。但是,解释性的文字很少使用。

电影和戏剧相同,都专注于可视信息和对话。在视觉呈现方面,电影更具灵活性。多镜头、特殊效果和后期编辑给电影提供了更大的空间。

电子游戏经常借助来源于其他媒介的技术。有些采用的是诗歌、短故事、小说、图片小说化的呈现、戏剧化的表演和类似电影的场景。但是,最强大的媒介来源于各种媒介优势的 相互作用。

动态。动态故事讲述并非只存在于电子游戏中。从对冒险书籍的选择到让观众得到发泄的戏剧,动态指的是故事中的可变和互动元素。

creativity(from critical-gaming)

讲述

虽然我们可能没有意识到,但是我们总是将故事与我们经历过的其他事情(游戏邦注:尤指其他故事)相比较来评估质量。换句话说,我们正在不断寻找原创故事。一方面我们因 熟悉的内容而感到厌烦,另一方面我们渴望得到新的内容。

创造性。许多人对复制产品不厌其烦。好像我们对创造性的价值评价越高,我们就越贬低复制品。所有的艺术都可以被看作是对生活的反映和重组并赋予其新的含义。我们很难对 原创性只有10%的故事表示欣赏。我们对故事设计的理解更深,我们就能更好地判断出某个作品的独特性。

系列。许多系列都是由较小的完整故事(游戏邦注:这些故事属于相同的媒介)组成的。我们很自然地以是否与系列路线相符来评估故事的质量。但是,单独考虑某个故事的度量 也非常重要。

跨媒体。跨媒体故事讲述是个首先由大学教师Henry Jenkins提出的概念,他在自己的书籍《Convergence Culture: Where Old and New Media Collide》中用此来定义多种媒体形 式中的故事讲述。这个想法的核心是各种形式的媒体相互支持,通过为读者提供不同的视角来整体化解释文字。通常来说,这些类型的文字有着丰富的内容和艺术风格,用户需要 投入更多的资金理解整个叙事网络。从这点上看,构建跨媒体专属作品就像是在构建包含万物的宇宙。

回响(和谐)

回响/和谐。这可以衡量故事的不同方面(游戏邦注:上文所述故事的组成部分)相互提升的程度。比如,有个名叫“循环”的故事的主题是循环,那么就可以出现以下这些和谐形 式:未来的世界不断循环回到之前的时代里。场景是个巨大的正在旋转的空间站。角色是那些害怕重新回到他们已经逃离的生活的罪犯。角色使用飞镖作为武器来战斗。步调和场 景进程中含有日夜循环。所有这些元素都与主题很相配。

如果某个故事都不含有上述元素,那么就不是个好故事。我们必须去除寻找那些铸就“差劲故事”细节的习惯。正如游戏设计那样,故事真正的冲击来源于所有小碎片。因为这个 过程很复杂,所以关注或把握单一细节或忽略细节只把握整体都不可行。讨论“劣质”故事的更好方式是解释故事的各个层面如何影响或摧毁其优秀品质。

让我们从我在本博文中经常提到的例子——NES游戏《超级马里奥兄弟》开始。通常,人们认为这款游戏中没有故事,这种想法是错误的。有人声称游戏中确实存在故事,但是故事 显得很无力,根本没有给游戏玩法提供背景。认为这款游戏中的故事很无力也是不准确的。无论你是否喜欢这款游戏,最好还是在这里剖析下各个部分以及如何相互配合。

《超级马里奥兄弟》(游戏邦注:下文简称SMB)的故事内容很直观,而且也是个相当简单的故事。游戏发生在蘑菇王国中,玩家在陆地、海洋、天空和城堡中冒险(游戏邦注:这 些是游戏的场景)。其中的马里奥、敌人和公主分别扮演着人们熟悉的英雄、对手和急待拯救的人(游戏邦注:这些是游戏的角色)。游戏主题是冒险、营救和英勇之举。故事情 节设置在动作平台之上,不断打通关卡并进入下一关,马里奥历经艰难险阻到达World 8-4。

超级马里奥兄弟(from news.duowan.com)

游戏的执行更为复杂。游戏中的文字很少,大部分内容通过视觉效果和游戏玩法来传达。所有无法操作的屏幕都是次要的,主要关注点是游戏场景。正因为其简单化,SMB不存在有 效性和连贯性的问题。毕竟,游戏中最为复杂的状况只是“我们的公主在另一个城堡里”。步调围绕8个难度逐渐增加的波段来设计。每个世界的波段分为4个关卡来呈现。然而在 这种鲁多叙事性结构中,变化程度也很大。不仅游戏中许多关卡有不同的通关方法,而且还有可以进一步改变游戏进程的弯道。某些玩家可能通过跳过游戏中多数关卡的方式在数 分钟时间内打通游戏。游戏玩家可能要花上很长的时间,因为要打通所有32个关卡。

在这款游戏发布之时,没有其他电子游戏采用类似的做法。所以,游戏无疑具有很高的创造性。回到20世纪80年代,电子游戏故事通常是在操作指南手册中阐述。你可以自行决定 要将游戏操作手册中的故事视为游戏的一部分还是只当做产品的一部分。如果你认为故事不属于游戏的一部分,那些位于游戏外的文字就可以算作是跨媒体元素。阅读下面的操作 手册,我会在下文中阐述其中最棒的部分。

“有一天,和平的蘑菇王国遭到库巴的侵略,这是个以黑魔法而闻名的海龟部族。爱好和平的蘑菇人民被变成了石头、砖块和农场中的植物,蘑菇王国支离破碎。唯一可以解开蘑 菇人民所中的魔法咒语并使他们恢复如初的人是Toadstool公主,她是蘑菇国王的女儿。不幸的是,她现在被库巴海龟国王关押了起来。英雄马里奥听说了蘑菇人民遭受的苦难,接 受了从邪恶的库巴手中救出蘑菇公主的任务,重建蘑菇人民被摧毁的王国。你就是马里奥!你需要从库巴的黑魔法中救出蘑菇人民!”

从根本上来说,SMB高度精确地阐述了相对简单的故事,因为讲述是电子游戏传达信息的最佳方式,随后是玩法(游戏邦注:即相互作用)和视觉效果。绝妙的玩法也对故事有所帮 助。对于那些忽视游戏故事的人来说,我敢说他们不可能尽情享受到游戏可玩性,也不会欣赏故事。简单地说,让马里奥从1-1到8-4是个故事和可玩性兼有的过程。

所以当你想要从整体上讨论游戏故事时,因为甚至连SMB中这么简单的故事都如此复杂并且含有多个层面,你应该像我这样进行综合性的描述。如果你没有耐性像我这样,你的分析 至少也应该触及所有内容和执行层面。如果你没有做足进行如此分析的准备,那么关注1到2个层面也能够得出很棒的结果。只是要注意,不可声称或暗示你的观点覆盖的是整个故 事。

举例说明

下文将列举在某些方面表现的格外出众的部分游戏。

内容

俄罗斯方块(from technabob.com)

场景。许多游戏设置在有趣的世界或地点。大家应该都记得,Gameboy版本的《俄罗斯方块》设置的场景是俄罗斯。《生化危机》、《传送门》和《侠盗猎车手》系列游戏的场景很 丰富,并且整合至叙事和游戏可玩性等其他部分中。还有些在这部分做的较好的游戏,包括《超级大战争:毁灭之日》、《旺达与巨像》和多数《塞尔达》系列游戏。事实上,我 们基本不会忽略游戏中的场景。如果场景确实很棒,就会引起我们的注意。如果场景不佳,我们就会关注故事的其他元素。

角色。相比其他媒介而言,视频游戏中的角色化会更为复杂。除了不同的角色风格之外(游戏邦注:比如圆滑或者有丰富的心理思维等),还需要考虑忽然出现的问题。游戏角色 可能具有可玩性,也可能不具可玩性。玩家的互动行为会以全新的方式影响角色化。《质量效应》中的Commander Shepard是个好人还是叛徒?或者两者都有?确实,这取决于玩家 的选择,但是这对我们的分析意味着什么呢?我们是否考虑玩家的所有选择?是否有可能做到这样呢?

可变性和玩家决定并不总是游戏主角才会面临问题。还存在某些极端的例子,比如在《RO9》中玩家需要同时控制9个角色,在《Poto & Cabenga》中玩家需要控制2个角色。在某些 游戏中,玩家会依此控制多个角色。

我喜欢像GlaDos和Linebeck等有着复杂心理活动的角色,也喜欢像马里奥之类平凡的角色。优秀的故事可以整合任何风格的角色。

情节。故事是一系列某时在某地发生的事件的集合,其中蕴含着角色(游戏邦注:包括某些类似角色的东西)。事件由各种各样的动作组合而成。事件如何连接可能非常复杂,但 是我们必须考虑情节如何发展并达到高潮。诸如《最终幻想6》之类的RPG很好地将许多角色和时间融入到史诗般的情节中。《塞尔达》系列游戏也是个很棒的例子,在情节推进中 像林克之类的小孩子逐渐变成了勇敢的英雄。有些游戏的情节从头到尾都很清晰,比如说《旺达与巨像》。如果你需要杀死16个巨像方能救下那个小女孩,那么每个巨像的死亡都 会引导你挑战下个巨像。

复杂性/简单性。这个层面需要做些许解释。在复杂的这个极端,有《质量效应》、《塞尔达》系列和《魔兽世界》等MMO游戏。这些游戏都有着大量角色、背景故事和其他细节内 容。在简单这个极端,有《超级马里奥兄弟》以及《索尼克》等老游戏。这些游戏的细节内容很少,也很少有丰富的背景故事。

主题。最贴近故事核心含义的是故事的主题。我们从学校的学习中得知,故事更多的是交流而不只是简单的含有角色的事件。我知道如果没有了连接故事各个层面的主题,这样的 故事并没有多大价值。或者说没有了含义的故事仅仅是一堆相互独立的细节而已。但是对我来说,这种看待问题的方法不是很恰当。

一旦你意识到所有的文化都有着抽象的想法而且人类会将自已的文化灌输到所有他们创造的事物中,你就会明白每个艺术作品都有着更深层次的含义。而且,我们每个人在分析时 都带有这自己的偏见和文化概念,使得观察事物带有内在的复杂性。我们应该关心的是如何找到含义,而不是找到其来源。

我会列举某些有着明显主题的游戏实例。《塞尔达传说:幻影沙漏》有着死亡、梦想和抱负和勇气的力量等主题。《超级大战争:毁灭之日》的主题是反对彻底的荒凉以及生存和 人性。《口袋妖怪:黑与白》大胆引进了个人真理、个人选择和混合现实的主题。《神秘海域2》的主题是寻找财宝。《银河战士:另一个M》的主题是自然与角色培养。《超级马 里奥:银河》系列游戏的主题是以损失、诞生和改变宇宙的力量。

执行

效能。一般来说,电子游戏的故事效能主要受到了故事场景和游戏设置的影响。为了不把这一元素与步调元素混淆在一起,我们只需要考虑故事内容的设计空间,艺术设计等等元 素。如果故事中反复出现相同的地点,定位,人物角色或场景等,那么可以说,这个故事的效能大大降低了。如果你已经感受到一个故事开始重复一些情节,主题或者场景,那么 你可以考虑缩减这些重复内容的出现。《仙乐传说》就是一款在功能角色(即游戏设置)和叙述角色中充斥着太多类似地点,角色和场景的游戏。所以,我们可以看到那些过于重 视于游戏设置的电子游戏,经常会出现故事效能的大大流失的问题。

条理性。一个故事中的任何细节都不能有相互矛盾问题出现。而“ludonarrative dissonance”(游戏邦注:ludonarrative是由原LucasArts创意总监Clint Hocking提出,这是一 个合成词,由ludology和narrative两个单词组成,意指游戏故事与玩法之间的冲突)便是防止电子游戏故事丢失其条理性的一大广为人知的方法。与效能元素一样,我们知道游戏 的故事内容必须与游戏设置紧密结合在一起,但是因此却可能会影响,甚至破坏故事内容的呈现。因为电子游戏的设计始终围绕着一些抽象且非和谐的因素,而随着游戏的进行, 这些因素可能会不定期地发生变化。例如在游戏《最终幻想7》)中,士兵在游戏的一开始就朝玩家扮演的角色发射子弹。但是这种出击却未对玩家的生命值(HP)造成太大的影响 。是否说这些枪弹的威力太弱了,或者这些游戏角色太坚不可摧?这些都难以判断。事实上,在很多电子游戏中,任何角色都有可能从一系列的暴力对抗中幸存下来。因为对于玩 家来说,我们宁愿接受游戏中的抽象因素和解释,也不愿意接受游戏主角因为一颗小小的子弹就毙命。在像《光晕:致远星》等游戏中,也同样出现了这种带有故事性的“子弹” 。

光晕:致远星(from gamefy.cn)

步调。对于每一个波段来说,故事的高潮都是随着故事性和戏剧化的能量或者说是一种紧张感的形成而产生。在游戏设置的步调方面,同样也需要借鉴一些类似,或者是更有难度 的游戏设置理念。与执行元素的其它方面相同,我们同样也必须考虑如何做才能让故事的步调与游戏设置相匹配。《魔法门之英雄交锋》便着重于突出多个不同的游戏章节。而在 每一个章节中,都会出现一个新的角色,并且从级别“0”开始执行游戏任务。这些章节在一开始难度都很低,但是随着游戏的进行,玩家将会面临更多更厉害的敌人,甚至是最后 的终极对手。当整个游戏故事完全形成时,游戏设置的难度级别也会经过多次重置而最终形成。而且这种不协调在游戏的最后一章会变得最为明显。在最后一章节,玩家并非投入 最后的战斗,而是重新操纵一个新的角色,进行一场相对简单的战斗。

风格/语言。《Super Smash Brothers Brawl: Subspace Emissary》和《超级食肉男孩》的故事场景是以一种无声影片的形式呈现出来。没有对话或者文本,只有视觉上的叙述传 达。《最终幻想6》让玩家感受到了一种亲临电影院的真实体验。屏幕上的游戏角色不断地进行一些夸张的肢体语言,向我们这些观众们进行自我展示。而就像我们在剧本中会看到 的情形一样,这款游戏的每一个角色的出现都伴随着属于自己的音乐主题和个性化描述。而那些单纯借鉴日本漫画中故事模式的游戏,则只会通过呆板的对话场景像观众透露游戏 信息,例如《超级大战争》系列游戏,《仙乐传说》和《美妙世界》等游戏。当然了,还有一些是被认为拥有电影般完美效果的游戏,如《神秘海域》,《天剑》和《光晕:致远 星》等。

媒介。在这系列文章中的第一部分,我已经列举了一些带有其它媒介特征的游戏案例。因为电子游戏设计者能够自行挑选其认为合适的特定媒介元素,所以对于电子游戏的设计来 说,这一领域并未存在任何单一的媒介选择判断标准。换句话说,现代游戏既可以选择配音形式,也可以通过文本描述展现游戏。而且也未存在任何说法能够判断哪一种模式更好 。我为何如此强调解释这一观点,正是因为有太多人固执地相信电影模式表达方法才是所有游戏都必须遵循的唯一章法。

动态。有一些游戏强调区分不同的叙述途径,并鼓励玩家在游戏中努力探索各种可能性因素,这种游戏包括《光辉物语》,《奥伽战争:命运之轮》,穆修拉的假面和《质量效应 》。但是也有一些游戏开发者并不支持玩家去探索游戏故事中的多种可能性,如《暴雨》。虽然说这些游戏都是一些较为典型的例子,但是我们必须知道,像在《超级马里奥》这 种游戏平台中,空间的转换也会因此改变游戏设置的叙述表现。按照这种方法,大部分游戏将呈现出动态化/非固定的游戏设置,而因此表现出一些多层次的动态化叙述模式。所以 说这种类型的游戏是参考了动态化非游戏设置元素而制作出来的游戏。“支线任务”(游戏邦注:即详细流程)可以说是动态化游戏故事特征的显著表现。

讲述

创造性。不管我们是否喜欢特殊元素,所有的游戏在某种程度上都具有一定的创造性。我们很乐于看到自己的作品比其它作品更特别,且更具有创造性,然而实际上,这种比较却 是一件非常困难的任务。因为没有一个玩家能玩遍所有的游戏,甚至不可能精通特定某种风格的游戏。即便真有人不得不玩大量游戏,他们也总能通过深入研究一款游戏,找到其 故事内容之外的其他特点。所以,如果单纯依靠细节比较来决定一部游戏作品的创造性,那么你将永远得不到想要的答案。相反的,如果我们能够适当地审视我们的相关评价(游 戏邦注:即那些基于游戏系列或风格等评价),那么我们便能触及创造性这个话题,特别是当我们能够辨别一款电子游戏是否是拙劣的复制品时,我们便能够抓住创造性。 《Linear RPG》,《You Must Burn the Rope》以及《Super PSTW Action RPG》都是很好的例子。如果你一直执拗于这些游戏只是一些拙劣的复制品,那么你便不能感受到它们优 秀的游戏设置和出色的故事情节。我看过一个视频(链接:http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4Z2Z23SAFVA),该视频制作者可以说完全不理解我所提到的这种创造性,因此才会 制作出如此滑稽可笑的视频。在某种程度上,复制其它作品对于这些游戏来说并非完全是坏事。而且,幸运的是,这些游戏模仿的痕迹并不多,而且都能抓住重点以突出自己游戏 所要表达的亮点。

系列。游戏续集和游戏系列的魅力不可阻挡。在众多媒介中,故事系列和IP品牌在推动新产品的销售过程中都有着功不可没的作用。我们总是喜欢一些相同的事物,并且渴望知道 完整的故事情节。所以,当玩家在挑战一个游戏系列时,总是享受着游戏中贯穿始终的细节,同样地,如果系列游戏失去了连贯性,那么玩家便会因此感到失望。就像《塞尔达传 说》,虽然这并不是一款基于故事内容展开的系列游戏,但是却仍有很多玩家尝试着去把每一个游戏系列的故事串在一起。甚至有些玩家认为《银河战士》的故事内容必须与《银 河战士:猎人》以及《银河战士弹珠台》串联成一个完整的故事情节。这个元素能够将许多相对独立的游戏故事有条理地贯穿在一起。

跨媒体作品。《光晕》是一款很受欢迎的电子游戏系列。这部作品可以说是动画短片,漫画与小说的结合体。我们甚至还能在游戏中看到一部绯闻电影的影子。而这些元素都集中 在一起,汇聚着《光晕》这个巨大的宇宙。《死亡空间》和《银河战士》都是较为出色的跨媒体作品。

共鸣(和谐)

匹配游戏故事和游戏设置很难,但是如果能做好,将能为电子游戏带来不错的反响。然后,故事中的任何两个元素都能产生相互的共鸣作用。最为突出的便是主题元素,它能够轻 易地与其它元素产生共鸣。因为主题是一相对抽象的元素,能够灵活地与其它具体元素,如环境,角色和情节相呼应。我特别欣赏《时空幻境》中的诗歌文本和游戏设置所产生的 那种和谐感。游戏以诗歌的基调去描述主人公Tim的过去,流露出爱,失落与渴望的情感。而这些抽象的概念与游戏设置中的挑战和机制很好地结合在了一起。例如悔恨的情绪让 Tim想要重新回到过去,试着去解决并挽回一些事情。而游戏设置使得玩家能够回到过去,尽力做出挽救。通过这种和谐的共鸣,我们能够通过Tim在游戏中解决问题的行动而去思 考更多关于角色的问题,例如是否Tim比以前更加聪明了?或者我们是否真的能够回到过去挽救一些已经发生了的事情等等。

篇目2,分析交互式故事的5个核心元素

作者:Thomas Grip

前言

过去几年,我越来越觉得,电子游戏的故事没有成为它本来应该成为的样子。关键问题不是出在文字、主题、角色之类的东西上,而是在于整体表达上。当我玩游戏时,总是有些东西阻止我真正地体会游戏剧情。思考了这个问题相当长一段时间后,我想到了5个元素,我认为是它们是优秀的交互式故事的核心所在。

以下是我对这个问题的看法,只是个人观点,绝对算不上什么严谨的科学理论。也就是说,我认为我提出的5个核心元素不是浅薄的原则也不是小众美学的总结。我确实认为,它们可以成为改进游戏故事的一个理想的基础框架,体现了大部分人对交互式故事的期待。

另外,以下所列元素都是必须的,丢掉任何一个都会破坏故事体验。

1、剧情是焦点

这是非常简单的一点:游戏必须从头到尾叙述故事。不一定是关于谜题、收集宝石或射击移动目标的游戏。游戏可以包含各种特征,但这些都不能成为体验的核心。游戏存在的原因必须是让玩家沉浸于故事中;其他特征的地位都不能高于这一点。

为什么?理由是显而易见的。希望表达故事的游戏当然必须专注于这一点。下文中提到的几个问题就是直接由于不重视这个元素导致的。

这个元素的关键方面是,故事必须是具体实在的。它必须包含可信的角色和背景以及一定的戏剧性。游戏的故事不能太抽象、太简单或缺少有趣的、故事相关的事件。

2、大部分时间是在玩游戏

电子游戏是一种互动媒体,因此体验必须包含某些形式的互动作用。游戏的核心不应该是阅读或观看过场动画,而应该是玩这个行为本身。这并不是说互动活动必须是持续不断的;仍然必须有一些中断时间,甚至非连续性也可能是必要的。

以上说法听起来相当简单,简直是游戏设计的基础,但并不明显。游戏设计的一个普遍法则是,选择是王道,正如Sid Meier曾经精辟地总结道:“游戏是一系列有趣的选择。”然而,我不认为这对于交互式故事也是完全适用的。如果选择就是一切,那么“选择你自己的冒险”系列丛书不就是终极交互式小说了吗?—-然而它们并不是。某些以剧情为主的知名游戏甚至完全没有任何与故事相关的选择(游戏邦注:《末日余生》就是一个例子)。鉴于这一点,我不禁怀疑:交互性真的那么重要吗?

The Last of Us(from nerdsraging)

交互性确实重要,但不是指做选择。我的观点是,交互性在故事中的主要意义是创造一种存在感,一种置身于游戏世界的感觉。为了达到这个目标, 必须有一个稳定的主动操作(玩游戏)的过程。如果玩家太长时间处于被动状态,那么他们就会脱离体验,特别是在当玩家感觉他们应该有控制权的环节的时候。游戏必须总是致力于保持和强化“存在感”。

3、交互活动必须有剧情感

为了让玩家融入故事,他们的行动必须与重要的事件有一定相关性。玩法一定要与故事相关,哪怕是一点点相关。原因有二:

第一,玩家必须觉得他们是故事的主动参与者而不只是一个被动观察者。如果故事没有任何重要事件与玩家相关,那么他们就会变成被动的参与者。如果游戏的玩法基本上就是匹配消除宝石,那么玩家是否花99%的时间与游戏产生交互作用,也就不重要了;他们不是重要事件的一部分,所以他们的行动是无关的。玩法必须成为故事的基础,而不只是一种用于等待下一个场景的辅助活动。

第二,玩家必须能够从行动中理解自己的作用。如果玩家扮演的是一名侦探,那么这一点必须从玩法中体现出来。需要借助过场动画之类的东西来解释玩家的作用的游戏,其实就是没有把故事讲好。

4、无重复性行动

许多游戏的核心沉浸感来源于精通系统。玩家在游戏中花的时间越长,他们就会对游戏越熟悉。为了使这个过程生效,玩家的行动必须是重复的。但优秀的故事中不应该出现重复性活动。相反地,我们希望活动持续的时间符合游戏节奏的需要。玩家玩游戏不是为了精通某些机制,而是成为好游戏中的一个角色。当一个活动已经完成它的目标,希望把故事讲好的游戏就必须继续进展。

重复性的另一个问题是,它破坏了玩家的想象力。许多媒体依赖受众的想象力来填补故事事件之间的空隙。电影和小说就非常依赖受众的个人解读。但如果相同的活动反复发生,想象的空间就会越来越小。最终,玩家再也无力填补这些空隙,于是就觉得故事太死板。

这并不意味着核心机制必须不断改变,而是说机制的使用方法必须有所变化。《地狱边境》和《时空幻境》都是突出的例子。在这些游戏中,玩家可以很快学会基本的玩法,但在整个体验过程中,游戏仍然不断变化机制的表现形式。

5、主进程无阻塞点

为了把玩家留在故事中,他们的注意力必须始终停留在故事事件上。这当然不是说不应该遇到挑战,但必须保证这些阻碍不会太占用玩家的注意力。务必记住,玩家玩游戏是为了体验故事。如果他们卡在某个点上,他们的注意力就会从故事转移到单纯地通关上。进而,玩家会开始挖掘游戏的深层机制。这两种情况都会严重破坏故事体验。

造成这个问题的主要有三个原因:谜题太复杂或含糊、对技术要求太高或环境如迷宫般曲折。许多游戏都在这三点上犯了错,玩家进展不下去也往往是因为它们,要么是不知道接下来应该干什么,要么是不具备继续进展所需的技术。不是说不能使用谜题、迷宫或技术性挑战,而是必须保证它们不会阻碍体验。如果这些挑战会阻碍玩家体验故事,那么就必须剔除。

什么游戏达到以上所有要求?

这5个条件似乎是很明显的。当我写这篇文章时,我经常觉得我所写的东西已经是常识了。但为什么还有那么多游戏达不到要求呢?想到这一点,我觉得很是吃惊。这些元素提出的条件是相当普遍的,但全部满足的游戏却非常罕见。

纯故事性游戏的最佳代表似乎就是视觉系小说。但这类小说在第2个元素上失败了;它们的交互性太低,玩家基本上沦为读者。它们在第3个元素上也做得不好,因为它们给玩家提供太多与故事相关的活动(基本上是以被动方式展示出来)。

动作游戏如《末日余生》和《生化奇兵之无限》在第4和第5个元素上表现不佳。此外,这些游戏在很大程度上也达不到第3个元素的要求。它们经常用过场动画来表现故事内容,这意味着它们中有些也不满足第2个元素的要求。RPG类游戏也不能幸免,因为他们通常包含太多重复性元素。它们往往有太长的中断时间,因为过场动画和对话太多。

游戏如《暴雨》和《行尸走肉》让人觉得非常接近于交互式故事,但在第2个元素上达不到预期效果。这些游戏基本上是带有交互性的电影。虽然交互性是体验不可分割的一部分,但还发挥不了主要作用。另外,除了少数要求反应能力的玩法,确实比其他游戏更讲究思考和计划。这就大大损害了游戏本应该有的沉浸感。

那么,到底有什么游戏完全具备以上5点元素呢?因为各个元素的要求都不是非常具体,所以有没有满足条件取决于评估方法。我认为最接近要求的游戏是《Thirty Flights of Loving》,但它有一个小问题,那就是故事太奇怪太零碎了。所以,它仍然不是具备5点元素的游戏。另一个比较接近的是《The Moon》,但它的对话和过场动画太多。《Gone Home》也比较接近,但玩家活动和核心故事之间的关联性太弱,操作的时间太少,阅读的时间太多。

无论你是否认为这些游戏满足5大元素的要求,我觉得它们多少是有突破的。如果我们想改进故事,可以从它们当中汲取灵感。另外,我想指出,这些游戏在评论和商业上都收获成功了,所以显然它们有值得借鉴和欣赏的地方。

总结

这些元素与游戏的品质无关。达不到以上任何一点要求的游戏仍然有可能是一款出色的游戏,但不能标榜它的故事具有丰富的可玩性和交互性。同样地,完全满足以上要求的游戏也可能是劣质品。这些元素只是描绘了某种体验的基础轮廓。我认为,那种体验在今天的电子游戏中几乎是不存在的。

我希望开发者在计划和评估自己的项目时能考虑到这5点。能不能按这条思路做出游戏还是一个有待解答的问题,毕竟在这方面的探索还不多。但接近具备所有这些元素的游戏确实包罗了多种体验。我毫不怀疑,这是一条非常有希望的探索道路。

注:

我漏掉的交互性的另一个重要方面是计划的能力。当以《行尸走肉》和《暴雨》为例子时,我稍微提到了这一点,但它还值得进一步挖掘。优秀的玩法交互活动不是要求玩家按各种键,而是玩家活动对游戏的未来状态有影响。当玩家执行输入时,玩家应该是在模拟他们头脑中想到的结果。即使玩家的想象只持续相当短的时间(如“现在必须射击飞来的小行星了”),但效果是大不同的,因为现在玩家的输入已经不是单纯的条件反射了。

什么叫作重复性?这个问题很值得讨论。例如,游戏如《Dear Esther》只有两种玩家动作:走和看;实在没什么变化性可言。但因为场景是不断变化的,所以不会有人说活动太重复。有些游戏虽然提供了非常丰富的、复杂的动作,但如果游戏要求玩家在类似的场景中不断执行这些动作,玩家仍然会觉得重复性太高。我认为可以说,重复性基本上是一个资源问题。用有限的资源做出无重复性的游戏是不可能的。这也意味着能把故事讲好的游戏必然是要求大量资源的。

我认为还有一些游戏也接近于具备所有元素的:《The Path》、《Journey》、《Everyday the Same Dream》、《Dinner Date》、《Imortall》和《Kentucky Route Zero》。它们是否成功,取决于不同的解读,因为它们都比较小众。它们仍然是值得关注的游戏。毕竟有了它们,我所认为的满足或至少接近满足上述五个元素的游戏列表才能完整。

篇目3,关于游戏故事创作过程的几点思考

作者:Poya Manouchehri

我有个想法:人人都会在特定时刻萌生某个故事构思。我这里指的并不是真实生活的故事,而是源自想象的故事内容。

这也许是一闪而过的想法,也许是个具体的某个人,也许是篇新闻报道,也许是个真实事件,或是突然激发故事构想的游戏。而将构思转化成完整内容的过程则是个另外一个故事。

Connectorium from gamesforsoul.com

我目前正在给游戏《Connectorium》编写故事。这是我继同他人共同制作“Revival”短片后编写的第二个故事。

文章只是关于这一过程的几点随想、观察及体会。

从空想到实践

这是创意过程的普遍特性。你从空白画布着手。这个构思也许非常抽象和模糊。然后通过各个句子、若干笔画、各补充注释、或各行代码,你进一步将抽象内容具体化。

但我发现这里有个关键点:这是个双向过程。原始构思会影响你创造的内容。但你所创造的内容也会逐步对构思产生影响。最终成品也许会和原始构思大相径庭。在我看来,这是创意过程的关键要素:过程的组织性。

随着故事的逐步发展,原始构思也许会变成截然不同的内容。也许是个具体的角色,或是个特定情节点。也许是个具体设置;也许是个游戏机制。无论如何,需记住的是,你的最终故事也许会和自己的原始构想完全不同。但这并不要紧,而且可能是件好事。

回顾过去

在我初次着手《Connectorium》时,我就对故事有总体把握。游戏围绕制度和关系,所以故事主要内容是:一个小女孩某天早晨醒来后发现自己来到不同的世界,在此她丧失自己原有的所有关系网。她的探险活动主要围绕她遇见的各种角色,帮助他们恢复缺失的关系网,破解其中秘密。

但一段时间后,我停下脚步,没有将故事进一步具体化。最后我问自己,为什么要浪费时间?为什么不继续创作故事?我忽然意识到:因为我不知道故事要如何收尾。

所以某天早晨,我带着自己的iPad来到一个安静的公园,一直到想出故事要如何收尾我才返回家中。这耗费我几个小时的时间,但最终我脑中忽然闪过一个想法。这里我脸上露出会心的笑容,因为我知道现在自己可以继续编写故事。

也许这更多和我偏好编写的故事类型有关,但我发现预先把握故事结局非常重要。所有游戏情节、角色和玩法都促使读者朝此结局靠拢。这令我的故事能够保持连贯性。

角色或情节

我最欣赏的一位作家Isaac Asimov经常因融入无趣的2D角色而遭受批评。尽管如此,他依然是位非常了不起的故事叙述者。

但我们不能说,优秀故事是精彩情节和逼真角色的结合体。就个人来说,我更注重情节元素。所以我总是需要留意角色的“单调性”。

出于这点原因,在完成这一故事的初稿后,我就内容进行了修改,更多着眼于单个角色,创作更多幕后故事,修复对话和描述内容,当然还有在必要时候调整情节内容。我觉得反向操作也行得通:创建详尽的有趣角色,围绕角色发展故事内容。

对话

对我来说,故事撰写最困难部分是对话。不仅是编写出逼真、自然的2-3个角色间的流畅对话颇有难度,更难的是要让所有角色听起来各不相同,而且栩栩如生。

最重要的是,这需要时间,需要靠重写进行完善。而编写角色的幕后故事也非常重要(游戏邦注:虽然这些内容不会向读者呈现)。它们从何处来?它们做什么?它们吃什么?它们的童年是什么样子?它们呈什么关系?它们的动机是什么?所有这些都会影响角色的说话方式、反应方式及自我表达方式。

另一令我从中受益匪浅的策略是,尝试描绘扮演此角色的真人。这也许是你认识的某个人,或是个演员。将外观和声音同对话进行搭配能够有效帮你查看内容是否匹配。有时以预期的角色声音大声读出对话也会令你从中有所收获。

游戏主题

关于故事元素,我已谈论很多,但在游戏方面涉猎的并不多。这里我要阐述自己的一个观点,也许有人会持不同看法。

我觉得玩法必须最大限度地强化故事内容。至少不能够同故事相抵触,因为这会促使你丧失游戏的沉浸性。你多常在游戏中东奔西跑,消灭各种不同元素,收集各种不同道具、数据,而这仅仅是因为游戏过场动画提醒你,你其实是在解决一个更大的冲突。

这里我要阐述另一个观点。故事模式多种多样,为什么很多故事,尤其是那些包含情节和角色元素的故事会将战斗设置成自己的核心机制?

我们是不是刻意回避未将战斗当作主要元素的故事内容?或者我们倾向在混合内容中植入战斗元素,无论它是否强化故事内容?

篇目4,如何为电子游戏编写一则杰出的故事(1)

作者:Winson

今天我想谈谈游戏领域最薄弱的环节:故事。

学校会教你如何提高语法,发音、词汇和如何使用形容词、副词、隐喻、比喻、头韵等写出更好的故事。但是你在高中所学到的这些技能却并不足以应用于视觉(电影)和交互媒体(游戏),有时候甚至还会带来适得其反的结果。所以除非你进入更令人头疼的大学,你永远也不会学到创造一则出色故事所需遵从的概念。可以说人们应该而非必须遵从这些概念。因为它们毕竟只是概念而非规则。

萌生想法

人们生成故事理念的方法有两种类型:

1.自发生成(脑中自发闪出想法)。

2.通过冥思苦想。

这两种方法的优势和劣势分别是什么?让我们先来谈谈第一种方法。

自发生成

*劣势:自发生成的想法通常会有些老调重弹和乏味。虽然并非所有情况均是如此,但如果你依赖灵感作为想法的来源,你实际上跟多数人的做法没有什么区别——想出那些已经被过度使用的明显理念。如果你是通过自发生成而得到的理念,就要加以选择地运用于自己的故事中。

它的另一个劣势就在于,你需要很长的自发思考时间才能想出足够数量的理念。即兴时刻可能很稀少,而依赖这一方法的人通常会拖延时间并最终退出。

*优势:有时候,你会因为这种自发生成的过程而令故事获得一个绝妙的想法。这个想法为故事增添了价值,并且你也知道如何取舍,毫不犹豫地抛弃那些陈腐或无聊的理念。有些时候,自发性还可以帮你克服“写作瓶颈”。

现在让我们来讨论第二种做法(冥思苦想)以及为何它应该成为你撰写故事的主要方法。

冥思苦想

这里有两种思考类型可以使用:其一是聚敛型思维,这是数学家所使用的思考类型。它通常意味着能够想出一个问题的答案。聚敛型思维当然在编写故事中也有其优势,但我打算专注于第二种冥思苦想型的思考。这就是所谓的发散性思维,它意味着“能够针对一个问题想出多个解决方案”。

要知道擅长创意的数学家、程序员或工程师数量如此之少,也是有原因的。他们的聚敛型思维高度发达,但却缺乏关于发散性思维的训练。人们对于创意来源于自发生成,人类生来具有创意或没有创意这个看法存在误区。事实并非如此:心理学家发现创意型人才极擅长发散思维。好消息在于发散性思维像其他技能一样,可以通过训练而得到提升。

*劣势:它的开发需要大量的脑力劳动,训练和时间。发散性思考者通常要创造大量内容和想法,他们对于要将哪个想法运用于自己的故事极为挑剔(其余内容就会被抛弃)。

假设你想创造一个场景。作为一名发散性思考者,你就会想出至少5个方法不同的播放场景。有时候你会想出10个、15个、20个甚至更多个不同方法,这些都得写下来,但你的故事中只会选择其中一个。想象一下为50个以上的场景重复这一过程,它马上就会令人生倦,并且需要大量的时间才能完成。

*优势:尽管编写故事的过程令人厌烦,但其最终结果却值得期待,因为你写出的可能是一个独一无二的有趣故事。你的故事不会是陈腐的旧篇章,因为你的做法与最糟糕的作家相反,并且精心选择了未被滥用的内容。你还能够更努力工作并且较少拖延时间,因为你并不会有太多“大脑一片空白”的时刻(要确保你最小化任何其他分心之事)。

所以总体来看,你的主要创意形成方法应该来自发散性思维,而非自发生成。但是,如果有个杰出的想法在你脑中闪现时,你就该抓住机会加以考虑。

展示而非讲述故事

你在学校中所学到的规则仍然适用于电影和游戏。无论你是想传达一个理念,一个主题或者只是说明,最好是使用视觉而非文字元素。你实际上应该最小化对话和文本数量。你该如何表现某位女性角色正在暗恋主角呢?你可以采用以下方法:

1.告诉观众“她暗恋你/他”。这种手段有多蹩脚?但还是有些游戏这么做了。

2.让该女性角色在与其他人的某次对话中表达自己对于主角的爱慕之情。

3.或者……你可以让她在看到主角出现时,适时地调整自己的发型或者检查自己的妆容。

只有当出现以下三种情况时,才能显示叙事或对话信息:

1.没有其他更方便的方法之时

2.对话用于自然的背景

3.为节省时间(加快游戏的节奏)

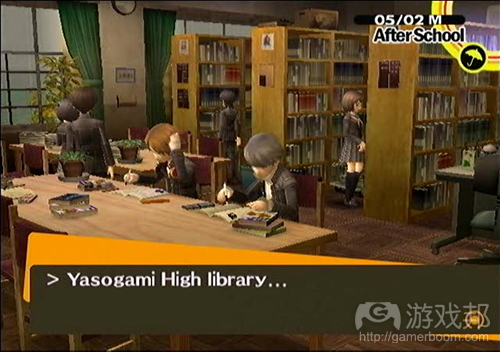

关于没有其他更方便的方法这方面的例子就是《Death Note》。其中的主角Light Yagami太聪明了,这要让观众理解其复杂的策略颇有难度,所以他们必须通过叙事(或者向Ryuk解释自己的计划这种对话)来传达信息。这里有一个你应该全力避开的可怕叙事方式。其中的例子来自《Persona 3》和《Persona 4》。

《Persona》游戏中几乎一切都是通过“叙述”来解释。看看这款游戏的以下截图,你就会明白我的意思:

persona-4-library(from gamingpoint)

人人都看得出这像是一个图书馆吧?所以其中的文本毫无意义并且浪费时间。

persona-4-rise-2(from gamingpoint)

我看到另一个截图时不得不摇头皱眉。它完全没有必要使用“你好像觉得自己更理解他们了”这种废话。

这些还都是小问题,它们的存在多数是缘于电子游戏的局限性,但这系列游戏真正摧毁玩家体验的问题在这里:它们使用对话传达故事的主题。在此我就不详述以免剧透游戏内容,但你绝不可如此操作以免它移除游戏对用户的情感影响。故事的意思应该留给观众自己去理解,而不是直接为他们展开……(游戏邦注:但也不是说你应该让故事主题模糊不清)。

使用主题撰写有意义的故事

你知道自己刚看到一部出色电影时的感觉吧?我要说说你在电影结束时获得的情感价值……也就是你觉得自己的生命被改变时的那种感觉。如果我想让观众体会同样的感觉 ,改变他们的人生观或者影响他们的一生,那你的故事就必须富有意义。

你该如何创造一个有意义的故事?首先,让我们来谈谈主题。什么是主题?根据维基百科,主题是中心话题。这方面的例子有善/恶,诚实/不忠,信任/谎言,爱/恨等。除了主题,故事中还有主题陈述。关于主题陈述的例子还包括:好人战胜恶人,忠诚得到奖励,真相被发现,爱情永恒等。但是,主题陈述并不会这么简单,作家应该进一步推进主题陈述,并提到“原因”或“时间”。要为主题陈述添加一些“因为”,例如好人不会相互背叛,所以他们能够战胜邪恶。你应该能够用一两句话概括自己的主题陈述。

关于这些话题每个人都有不同的观点。并非人人都相信邪不胜正,或者永远无法找到真相。这里的目标是选择你所相信的东西,将其隐晦地嵌入自己的故事中。看看你的整个故事并注意一下价值如何发生变化。故事一开始是由邪恶主宰世界,并以好人大获全胜而收尾吗?还是以爱情开场,以悲剧落幕?这正是你的主题需要考虑的表达方式。

一个更为复杂的方法:故事始于坏人掌握统治权,终于好人获胜,但却失去了自己的亲人。其主题陈述可以是:好人获胜,但付出了昂贵的代价。

让我们分析《To the Moon》这款游戏中的故事例子。它是一款很棒的游戏,只需要4、5个小时就能玩完。

to-the-moon(from gamingpoint)

如果你还没有玩过这款游戏,先看看这里的杂记:时日无多的Johnny奄奄一息地躺在病床上。你要扮演来自Sigmund公司(一家将虚假记忆植入病人脑中,完成其临终夙愿的公司)的Niel Watts和Eva Rosalene医生。Johnny的遗愿是登上月球,但他却不知道自己为何想去那里。为了实现他的愿望,他们必须找到病人为何想登月球的根源,这样Johny的记忆之旅就开始了。

分析《To the Moon》

《To the Moon》有三个主题:

1.爱

2.渴望

3.现实

为了找到故事的意义(各人都有不同理解),我们必须分析这些主题,以及它们自始至终的变化。让我们先分析第一个主题。故事始于Johnny孤独一人,他的妻子River已经过世。最终他们在NASA重聚,并乘坐太空飞船驶向月球。主题陈述1:真爱永恒……

我之前就说过,主题陈述不会这么简单,你应该指出真爱永恒的“时间”或“原因”。但是,我不会这样做,因为这可能产生不同的观点。

第二个主题围绕着Johny想去月球的渴望。这个主题从“不完整的目标”转变为“实现愿望”。主题陈述2:实现梦想。

最后一个主题从现实转变为非现实,因为这一切都只是发生在Johnny大脑中而非现实世界的过程。与其他主题不一样的是,它只是从积极转变为消极,这正是为何故事结局带有悲伤的缘故。主题陈述3:现实转变为非现实。

现在让我们将这些主题整合在一起,探索游戏的意义。主题1和2因Johnny想去月球的目标(他与妻子约定如果今生分离,就在月球团圆)而整合在一起。当然Johnny无法完整回忆起这件事,因为他在年轻时为了忘记创伤事件而服用了阻滞剂。所以尽管Johnny无法回忆自己为何想去月球,我们最终都会发现这要归因于他对River的感情。

最后一个主题陈述就变成:“真爱永恒在虚幻世界中梦想成真。”

所以《To the Moom》虽然仅有几乎不存在的机制,但却仍然不失为极为成功的游戏。其玩法本身很无趣,每个时空穿越的谜题也完全没有必要。其机制应该用于向观众传达主题。但是,玩家仍然为之所吸引,这大部分要归功于其“唯一”的故事情节,而在今天的游戏中我们几乎难以找到这种故事。想象一下在没有故事情节的情况下独自玩游戏的感觉……那一定是种糟糕的体验。我希望它的下个章节会出现更有趣的玩法。

《Persona 3》剧透

《Persona 3》是另一款极为成功的游戏,我相似这大部分要归功于其富有意义的主题。尽管其叙事故事的方法很糟糕,玩法机制也只是一般,但它还是具有值得人们学习的经验。我从这个系列游戏中学到的经验实实在在地影响了我的生活。当然,游戏机制也是《Person 3》和《Person 4》获得成功的一个重要因素。实际上,它们如此成功的一个重要原因就是其开发公司ATLUS使用了有助于传达主题的机制。

其社交联系机制促进了友谊主题的表达,而Persona的理念则促进了接纳与直相的主题。拥有过硬的机制是一回事,但它们必须与游戏相关,并且有助于展现机制。这一点无需再强调了。

我希望本文能够为游戏设计师或未来的游戏设计师提供一些有价值的见解。我认为这些概念比99%的人更能帮助你成为一名更好的作家,但是故事写作是一项非常艰难的工作,并且需要大量的掌握时间。你只有使用这些概念来训练故事写作才可能更上一层楼。这可能至少需要你花上几个月时间才能完成一个主要故事,有时候甚至需要一年以上。但事物均是如此,所以要保持耐心并努力工作,最终你也会撰写出像《To the Moon》一样精彩的故事。

篇目5,如何为电子游戏编写一则杰出的故事(2)

作者:Winston

在本文中,我们将贯穿更加理论化的分析,节奏,象征主义和锚定等等,我也将引导你们了解一些故事编写实践,这是每位作者的工具包中都必不可少的元素。让我们开始吧:

在之前的文章中(确保你在阅读这部分前了解了之前的内容),我讨论了使用主题去创造故事的意义。每一位作者都应该掌握这一方面的写作,他们也应该能够分析任何特定故事的主题。这在中学的英语中是个重要的主题,但当时我却彻底栽在这上面,因为老师从未有效地教授我们这些内容。所以以下是帮助你分析一个故事的主题一种简单的实践:

1.选择你最喜欢的故事(可能是来自一本小说,一部电影甚至是一款游戏)。

2.检查开始和结尾。注意有时候电影是从一个次要情节开始,之后才会出现主要情节。在这种情况下,你变可以检查两种清洁。

3.列出所发生的主题变化,例如憎恨变成喜欢,不公平变成公平,或者变成死去。然后为此编写相对应的主题陈述。

4.明确为了组成故事的意义,这些主题是如何结合在一起的。每个人都会拥有不同的看法,但是你的看法是最重要的。

5.(可选择的)在评论中写下你关于这一实践的答案。你也可以评论别人的答案(但不要太过激昂)。

你也许会问这一实践的要点是什么?除了能够完善你的分析能力外,你也能够重新感受(或重新阅读)你最喜欢的电影/游戏/书籍,并领会作曲家是如何巧妙地通过故事传达这些主题。你将能够为自己选择技巧,并获得灵感去写下带有类似主题的故事。

因为故事是围绕着主题发展,那这是否意味着你应该将其作为故事的起点呢?不幸的是,事情并没有这么简单。你当然可以使用来自自己最喜欢的电影/小说/游戏的主题并对其进行适当的调整,但通常情况下,从头开始创造故事意义的确是一件烦人的任务。所以作者们该怎么做?他们可以开始编写自己的故事,而一旦他们写了故事的开始和结尾,他们便会发现这是一个关于什么的故事。在那之后,作者必须从头开始重新优化故事以适应主题。好消息是:故事的结尾通常是被当成前期编写的内容。我将在之后对此进行分析,不过在此之前你需要了解更多相关主题的内容。

创造多样性

新手最常犯的错误便是他们会觉得“我将围绕着诚实的主题编写一个故事。”然后他们编写了只从正面角度传达的诚实,如如果你足够诚实,好运便会降临在你身上之类。这便是所谓的静态主题,如果观众长时间地体验到同样的情感,那么习惯性便会涌现出来。习惯性是心理学中的一个术语,意味着反复受到某些事物的影响而逐渐不能做出回应。过分显露出幸福的情感将导致玩家在面对这种感受时变得更加平淡。

主题应该在整个故事中不断受到挑战:“如果你在这种情况下表现出诚实,事情会变成怎样?”“当某种情况发生时你表现得不够诚实是否合理?”要记得,不管你的故事所传达的是什么信息,这都依赖于结局。如果它是完满的结局,你便可以基于正面视角去传达诚实,反之亦然。故事也可以是伴随着正面与负面的结合而结束,那么在这种情况下,它便能够同时描绘出诚实的正面与负面。

需要注意的是主题可以结合着一起出现,例如幸福可以伴随着友谊出现。习惯性的出现不只是针对于主题,同时也有可能因为节奏,行动以及对话的数量。总是强调高节奏的电影将会慢慢失去其效能,所以它应该适时地强调较慢的时刻。行动和对话也是如此,如果你的故事有时候没有对话,而你为了形成反差在其它场景中添加了对话,那么突然间角色的言语将会变得异常珍贵。

作为一名游戏设计师,你不仅需要考虑场景的发展节奏,同时也需要考虑游戏玩法的节奏。在《Persona 3》和《Persona 4》中,较慢的生活模拟机制总是能够够与紧张的战斗机制形成鲜明的对比。但情况并非始终如此,就像有时候当你花太多时间于模拟元素中,但却发现故事线中未出现任何有趣的内容。玩家经常会在这种时候觉得无聊。也许ATLUS应该识别出这种情况并在模拟元素期间包含以下更快节奏的内容。

最后,在我结束这部分前,让我们最后一次强调,主题与游戏设计具有巨大的联系。Schaglund曾经与我聊过主题,他说道:基于主题而非游戏线去考虑游戏设计非常有帮助,如此你便能够创造适合这些主题的机制。《时空幻境》中的“倒带”便是一个典型的例子,它能够辅助谅解的主题。《Persona 3》和《Persona 4》的社交联系机制也能够帮助描述友谊这个主题(游戏邦注:当你要获得更多社交联系时,你的能量便会变得越强大)。这遵循着机制–动态–没学(MDA)框架,即机制创造了能够生成没学的动态。

接下来让我们谈谈一个全新的话题:

象征主义

为了解释象征主义,我要简单地说下一个名为经典性条件反射的心理学科。有个名为Little Albert的知名实验,即名为“Albert”(并不是他的真名)将看到一些白色毛皮小动物。一开始,Albert并不害怕这些动物,但是接下来,当他再次看到这些毛茸茸的动物时是伴随着一个巨大的敲击声,从而让这个小孩产生恐惧。这两种情况反复出现着,Albert最终停留在对这种毛茸茸的动物的恐惧中。这时候,当眼前出现的是一只毛茸茸的兔子或老鼠时,他便会开始哭喊。

这一研究充满争议。但是也多亏了这一实验,我们能够对如何适当地使用象征主义提供一些基础:通过将一些刺激元素与特定的结果(可能是好的或者坏的)进行配对,我们可以从观众身上唤醒一些情感。然而,我们必须牢记住4件事:

1.为了确保有效性而需要多次配对。你不能在自己的故事中只是将蝴蝶与“危险”或“自由”进行一次配对,并期待着下次当你呈现蝴蝶时便能发挥作用。配对必须多次出现,并且通常是在观众未注意到的情况下。

2.我们已经在日常生活中习惯了某些事物,所以不需要在你的故事中再次去适应它们。例如,糖果=甜,烟=危险,蜘蛛=害怕等等。

3,不要尝试一些遥不可及的内容,例如将棒棒糖与枪战(危险)匹配在一起。此类的内容永远不可能发挥作用,因为远比想象中复杂。然而你却可以将棒棒糖与甜之外的其它内容匹配在一起,例如毒药/疾病。

4.象征主义的出现必须是自然的,或者不能让观众察觉到它。只要象征是用于一个自然环境中,它便无需躲避观众的意识。

最后,我想说的是象征主义的对象不需要是100%一样,但却必须足够相似。就像你可以使用不同颜色的蝴蝶去取代同一种蝴蝶,只要观众不会意识到奇怪之处你便能够继续下去,

有时候分析象征主义会很痛苦,所以我不会要求你这么做。如果你好奇的话,可以在空闲的时候基于自己最喜欢的电影进行尝试。

锚定

这是我在编写故事时最喜欢使用的一种技巧,实际上是我朋友想出“锚定”这一词,所以我不确定你是否能在网上找到它。从根本上来看它意味着:在故事线早期包含某些内容,它会在之后变得更加重要且更有意义。就像在《去月球》中,知兔子,玩具鸭嘴兽,甚至是Johnny前往月球的最后愿望在你刚开始玩游戏时都没什么意义。实际上,这真的很神秘,并且能够有效地让玩家沉浸于其中。然而当你在故事中前进时,所有的一切将慢慢得到解释,同时也会出现更多秘密。直到最后,即一切真相大白时,这将变成故事的转折点。

这是具有才能的作者的标志——即使隐瞒重要信息也能够确保观众沉浸于其中,并随着故事的发展慢慢释放出更多信息并创造出更多神秘感。这些时刻创造了故事的转折点,并引起了高潮,即故事最强大且最激动人心的部分。用于引向高潮的时刻必须基于较快的节奏,并在高潮后放慢速度。这是否能够让你想起早前的节奏图?如果你曾经受困于编写转折点或高潮,你可以着眼于自己看过的最感人的电影或像《去月球》等游戏,并尝试着模仿它们节奏风格。

我将这一锚定技巧分解成一个较容易使用的格式:

1.当你对自己想写的故事拥有一个非常基本的理念时,开始编写结局,把它当成是最重要的事之一。要记得,作为作者,我们要将最好的留到最后,所以这里存在一个技巧:写下你的故事中可能发生的最糟糕的内容。这将是你的故事最深入且最黑暗的秘密,并且能够用于创造转折点。《星球大战》中“我是你的父亲”的时刻,《Persona 3》中你发现世界将毁灭的时刻,以及《去月球》中Johnny向River承诺再团聚。

lies vs truth(from gamingpoint)

2.接下来列出这些黑暗的秘密的“副作用”,并决定将哪个包含在自己的故事中。《去月球》中的例子:

副作用:实际上Johnny并不知道自己前往月球的动机是什么,这是归因于他在使用受体阻滞剂。

副作用:实际上River一直在制作那些纸兔子,以此去提醒Johnny他们的第一次见面。

副作用:Johnny的妈妈唤他“Joey”,因为他的兄弟已经死了。

《Persona 3》中的例子:

副作用:在你睡觉时神秘的男孩出现了。

副作用:神秘的地方叫做Tartarus。

副作用:神秘的群组被称为“Strega”。

其实在这两款游戏中不只出现了这些副作用,我并未将其全部罗列出来,但是你需要抓住要点。这些游戏喜欢使用秘密去吸引用户的注意。但你必须小心不要包括太多可能泄露故事秘密的线索。

3.评价这些“秘密”是否是可预测的。如果你认为用户没有多少机会去猜测它是什么,你就应该在故事中包含以下内容将他们带离真相。带给用户惊喜,并提供他们并未猜到的内容。

你可以将这些黑暗秘密当成是微妙的悬吊管,即不需要将故事带离其目的。举个例子来说吧,在《去月球》中,实际上Neil在最后使用了止痛药,实际上当他在与松鼠相抗衡时健康状况并不是很理想。这些都暗示着他正在失去活力,但这在第一章节时并未呈现出来。也许我们将看到Neil作为“一只鸟的故事”中的病人。

顺便一提的是,这并不是编写故事的一种格式,这只是我想要使用的一种方法。并非所有故事都遵循着“锚定”的原则,就像比起秘密还存在其它方式能够确保用户沉浸于游戏中。我只是喜欢提供给用户他们并未想到的内容并通过故事的秘密去刺激他们的理念。

你们必须牢记,实践和努力是成为一名成功的作者的关键。所以使用你今天所学到的内容并亲自去编写一个故事吧。

篇目1,篇目2,篇目3,篇目4,篇目5(本文由游戏邦编译,转载请注明来源,或咨询微信zhengjintiao)

Story Design pt.1

Richard Terrell

There’s something I highly respect and value that I need to make clear up front. It’s your opinion, your feelings, and your personal story. Seems like a strange way to open an article about the craft of stories in video games and other media. But, believe me, stories are perhaps the most important tool we have for understanding the world and each other.

I have a degree in English with a concentration in creative writing. So, story design is my area of study. Over the years I’ve found that many talk as if they understand what a story is and how its parts work, yet their statements are far from anything substantive. Before one can talk about what a story is, it helps to be clear about the parts of a story.

I started the Critical-Gaming blog by creating a bridge between the theories of literary critique and game design. I figured that starting with something familiar (stories) we could understand game design more easily. From there I created and defined many terms and explained why descriptors like “good” are utterly imprecise and unhelpful. The idea is by breaking down every facet of game design, we can be more clear about what’s happening design wise, which

would in turn shed light on why we like or dislike a particular aspect of a game. I think this is a solid approach. So it’s time to do it again with stories.

The following is a universal system to break down and compare all types of stories. While I’ve come up with some revolutionary and radical game design theories in the past, I believe tackling story design will be much simpler. Our intuitions about the craft of storytelling should go a long way here. So, be patient if it all seems somewhat obvious.

To best understand stories, we must understand three main categories: content, execution, and discourse.

CONTENT

A story is nothing more than a series of events. Before we worry about deeper meaning or execution, we must focus on the fundamental details or the content.

Setting. The place where the story is set. Everything from the universe, world, country, town, and time period make up the setting.

Characters. “The representation of a person in a narrative or dramatic work of art” wiki. Flat, round, foil, realistic, absurd, lead, support, human, animal, ethereal; Characters come in all varieties. Realism is not best type of character. Rather, being relatable or functional to the story are qualities that can be just as, or more, important.

Plot. “A literary term for which the events that make up a story, particularly as they relate to one another in a pattern, a sequence, through cause and effect, or by coincidence” wiki. Action and conflict are two categories that can fit inside plot.

Complexity/Simplicity. Details create complex stories. Some tales are rich with many characters, locations, and back stories about everything. Other stories do very well with very few of these elements.

Theme. General or abstract ideas, messages, or morals. Motifs (reoccuring symbolic elements) can develop the theme.

EXECUTION

Stories are more than a collection of details or a list of qualities. Whether linear or non-linear, how the events are presented is storytelling or execution. If the execution is too slow, too obvious, too jumbled, or too fast even the best story content can fail.

Efficiency. It’s all about doing more with less. Conveying more story content with fewer scenes, lines of dialog, locations, actions, events, and fewer repeated scenarios is efficient storytelling.

Coherence. It’s possible to take a completely simple and straight forward story, cut it up, and rearrange it so that it’s incredibly difficult to understand. Since storytelling is the process of presenting narrative events, the order and the delivery shapes how coherent the work is.

Pacing. Small poems can be like emotionally charged snapshots. Short stories tend to feature a small wave of exposition, action, climax, and resolution. Long running series, novels, and others large stories generally contain multiple “waves.” How quickly these waves come and go and how steep they are is a simple way to think of pacing.

Style/Language. On first thought, the obvious idea here is verbal languages like English or Japanese. But there are also colloquial terms, lexicon, body language, cultural symbols, inside jokes, and other examples that qualify. Style is very broad category. Any way you of conveying information that you can think of can contribute to the style of storytelling.

Medium. Every medium has pros and cons. As a result, every medium has developed particular methods of storytelling based on their strengths. While these methods work great for each medium, they tend not to work so well in others.

Poetry excels in concentrated text where every punctuation, letter, and formatting decision matters. Rhythm and form help to create layered contrast and juxtaposition.

Short stories do well presenting snapshots and slices of narrative. By selecting a few key moments, rich story waves can be conveyed in a relatively compact space.

Novels are large works filled with many details. With so much text, writing to the fine degree that poems and some shorts stories feature isn’t practical. The delivery in novels tends to be more direct. (In general, written language excels at introspection because reading text mimics inner thought).

Graphic Novels/Manga/Comics use a combination of images to convey information and blocks of text to where the images fall short. There’s always a balance between whether information will be shown or told.

Plays/Musicals use lots of dialog and staging (positioning). Expressive, visual storytelling is important. Also, explanatory or expository text is sparingly used.

Films/Movies are similar to plays in that they focus on visuals and dialog. Films have a lot more flexibility when it comes to visual presentation. Multiple cameras, special effects, and editing give films the edge.

Video games often borrow technqiues from other mediums. Some offer poetry (Braid), short stories (Lost Odyssey), novels (Wow? Halo? Mass Effect, Ni No Kuni), graphic novel like presentation (XIII, Metal Gear Acid, inFAMOUS), play like performances (Facade, FF6), and movie like scenes (Heavenly Sword, GTA4, Metal Gear Solid 4). Some pull it off better than others. But ultimately, the strength of the medium comes from interactivity.

Dynamic. Video games aren’t the only source for dynamic storytelling. From choose your own adventure books to plays that work off the audience, dynamics refers to how the variable/interactive elements of a story.

DISCOURSE

Though we may not do it consciously, we’re always evaluating the quality of a story based on how it compares to everything else we’ve experienced (especially other stories). In other words, we’re constantly looking for originality. On the one hand we’re drawn toward the familiar. Yet, on the other we crave the new. It’s a tricky line that most of us don’t realize we walk.

Creativity. Many people are turned off by copycats. It seems that the higher we value creativitiy, the more we devalue replicas. All art can be thought of as the reflection, repacking, and repurposing of life (which includes art). It can be hard appreciating a story for its 10% creativity when you’ve seen the other 90% before in another work. The better we understand the design of stories, the better we can determine how unique one work is to another.

Series. Many series are a collection of smaller complete stories (within the same medium). Naturally, we evaluate the quality of later entries by how they keep in line with the series. However, it’s important to consider the merits of a story as an individual entry.

Transmedia. Danielprimed puts it best: “Trans-media storytelling is a concept first put forward by academic Henry Jenkins in his book Convergence Culture: Where Old and New Media Collide to define storytelling told over multiple forms of media. The crux of the idea is that each form of media supports the others and provides the reader with different, medium-specific viewpoints in which to interpret the text as a whole. Naturally, these types of texts are rich in

content and artistic styles, commanding a dedicated user base who are required to spend more money to invest in the entire narrative web. In this regard, building a trans-media franchise is like building a universe.”

Resonance (Harmony)

Resonance/Harmony. This is a measure of how well different facets of a story (listed above) enhance each other. For example, if there’s a story called Cycles and the theme is cycles there could be harmony in the following ways: The conceit is of a futuristic world that slowly phases through time cycling back to previous years. The setting is a giant space station ring that spins in place. The characters are criminals afraid of relapsing back into the life they run away from. The characters battle with boomerangs like weapons. The pacing and scene progression runs on a cyclical day/night cycle. All of these elements would resonate or harmoize nicely with the theme.

If a story has one of these elements great. If it doesn’t, it’s no big deal. One habit that we must move away from is looking for the details that make a “bad story.” Like with game design, the real impact of a story emerges from all of the smaller pieces. Because this process is so complicated, it not very helpful or accurate to look at an individual detail, or lack of a detail, then judge the whole. A better way to discuss “bad” stories is to explain how various facets actually undermine or deconstruct its better qualities. More on this later.

Story Design pt.2

Richard Terrell

Let’s start with the example that I always turn to on this blog; Super Mario Brothers for the NES. Often, people dismiss this game for having no story. This stance is just ignorant. Others claim that there is a story, but it’s flimsy and barely there to give the gameplay a bit of context. It doesn’t say much to call Mario’s story flimsy. Whether you like it or not, it’s better to offer a detailed explanation of its parts and how they work together. Let’s use the CED system.

Super Mario Brothers’s story content is pretty straightforward adding up to a fairly simple story. Set in the Mushroom Kingdom, players travel through land, sea, air, and castles (setting). Mario, Bowser, Peach, the toads, and all the enemies take on flat, familiar roles like hero, villain, citizen, and damsel (characters). The theme is adventuring, rescue, and bravery. And the plot is focused on action platforming where beating one level flows into the next and the next until Mario makes his way to World 8-4.

The execution is more complicated. With little text in the game, the vast majority of the content is conveyed through visuals and gameplay. All non-playable scenes are seconds long keeping the focus on the gameplay. Due to the simplicity, SMB doesn’t have a problem being efficient and coherent. After all, “but our princess is in another castle” is the most complex statement in the game. The pacing is generally designed around 8 waves of increasing difficulty. One

wave per world presented in 4 level groups. Yet in this ludonarrative structure, there’s significant variation Not only are there alternate paths through many levels in the game, but there are warps that can alter the progression further. One player may get through the game in a few minutes by skipping most of the levels in the game. Another may take the long route by playing through all 32 levels.

As for the Super Mario Brothers Discourse, at the time of its release there was no other video game like it. So, it definitely scores points for creativity. Back in the 1980′s it was the norm for video games stories to start inside the instruction manuals. You can decide for yourself if you consider Mario’s instruction manual story as part of the game or simply a part of the product. If you think it’s not part of the game, then does the external text count as a transmedia element. Read the instruction manual here. I’ve pulled out the best part below.

“One day the kingdom of the peaceful mushroom people was invaded by the Koopa, a tribe of turtles famous for their black magic. The quiet, peace-loving Mushroom People were turned into mere stones, bricks and even field horse-hair plants, and the Mushroom Kingdom fell into ruin.

The only one who can undo the magic spell on the Mushroom People and return them to their normal selves is the Princess Toadstool, the daughter of the Mushroom King. Unfortunately, she is presently in the hands of the great Koopa turtle king.

Mario, the hero of the story (maybe) hears about the Mushroom People’s plight and sets out on a quest to free the Mushroom Princess from the evil Koopa and restore the fallen kingdom of the Mushroom People.

You are Mario! It’s up to you to save the Mushroom People from the black magic of the Koopa!”

Ultimately, Super Mario Brothers delivers a relatively simple story at a high level of precision because the telling focuses on conveying information the best ways video games can; gameplay (interactivity) and then visuals. It also helps that the gameplay is excellent. For those who dismiss Mario’s story, I argue that it’s impossible to enjoy the gameplay and not appreciate the story. Put simply, the actions of getting Mario from 1-1 to 8-4 is the story and gameplay simultaneously.

So when you want to talk about a story overall, because even simple stories lia comprehensive description like I just made. If you’re not in the mood to do all the work, your analysis should at least touch on all of the content and execution facets. If you’re not prepared to make such an analysis, then focusing on one facet or two will produce better results. Just be sure not to claim or imply that your statements cover the whole story.

More Examples

The following is a list of video games that are notable for the following qualities.

Content

Setting. Many games are set in interesting worlds or locations. Remember, the Gameboy version of Tetris is set in Russia. For the purpose of story analysis we must be careful to look for examples that are well crafted as opposed to being just unique. The creativity category is a different matter that falls under the discourse category. BioShock, Portal, and the Grand Theft Auto series are a few popular examples of games where the setting is rich and integrated into other parts of the narrative and gameplay. Other good examples include Advance Wars: Days of Ruin, Shadow of the Colossus, and most of the games in Zelda series. In fact, it’s hard to mess up a setting. When it works we tend to notice. When there’s not much there, we tend to look to other elements of the story.

Characters. Characterization can be more complex in video games than in any other medium. In addition to various character types (flat, round, psychologically rich, etc), there are new perspective and emergent issues to consider. Game characters can either be non-playable or playable. Whether by a little or a lot, player interactivity opens up haracterization in new ways. Is Commander Shepard in Mass Effect a paragon or a renegade? Is he both? Yes, it

depends on player choices, but what does that mean for our analysis? Do we consider the entire range? Is that possible? Do we pick an interpretation and focus on it?

The variable and player determined character isn’t always a problem for the main character of the game. There are extreme examples like RO9 where players control 9 characters at once and Poto & Cabenga for 2 at once. Then there are more common examples like taking control of multiple characters one at a time like in Zelda: Phantom Hourglass, Zelda Spirit Tracks, the Advance Wars series, and the Professor Layton series.

As much as I love round characters with complex psychologies like GlaDos (Portal 1 & 2) and Linebeck (Phantom Hourglass), I also love the flat characters like Mario, Link, Donkey Kong, and the Prince (Katamari). Great stories can feature any combination of character types.

Plot. Stories are a series of events in place and time and they feature characters (or something like characters). Events are made of actions as simple as surviving to supernatural combat. Along with considerations of how events connect together, which can be quite complex due to non-linearity, we have to consider how the plot grows, climaxes, and resolves for both the gameplay and the story content simultaneously. RPGs like Final Fantasy 6 do a great job

weaving together many characters and events into an epic plot. The Zelda series is another great example that typically features a plot where little by little the child like Link fulfills the role of the courageous hero. Some plots are clear from start to finish like Shadow of the Colossus. If you need to kill 16 colossi to save the girl, then the death of each colossus leads right into the hunt for the next one.

Complexity/Simplicity. This facet needs little explanation. On the complex end there are games like Metal Gear Solid 4, Mass Effect, Animal Crossing, the Professor Layton Series, many games in the Zelda Series (Majora’s Mask, Phantom Hourglass, etc.), many MMOs like WOW, and the Resident Evil series. All these games feature lots of characters, backstories, or other details. On the simplicity end of the spectrum are games like the Super Mario Brothers series,

the Katamari series, Tetris Attack, BOXLIFE, Super Meat Boy, Donkey Kong Country Returns, Shadow of the Colossus, and many old school games including Sonic. The list goes on. There can be a lot of craft in a few details and little said in many.

Theme. No other facet of story content sits more closely to the core “meaning” and “about-ness” of a story than theme. Since the days of our gradeschool educations we’ve been taught to think about stories as communicating more than just simple events with characters. Uncovering the theme, (abstract, “big picture” ideas) is like finding that “ah-ha” Eureka moment. I know that without the theme that connects multiple facets of a story, some feel that such a story isn’t worth much. Or without that “extra layer” of meaning, a story is merely a bunch of independent details. To me, this is a strange and limiting way of looking at the issue.

Once you realize that all culture is steeped in abstract ideas and how humans cannot help but imbue whatever they create with their culture, you’ll see that any piece of art can be read for increasingly deeper meaning or commentary. Still, each of us carry our own biases and cultural lenses that make observing anything inherently complex. We naturally find patterns and we naturally see ourselves reflected in the world. We should worry about finding meaning, not

where it comes from.

I’ll list a few examples of games with obvious themes. Zelda Phantom Hourglass has themes of death, dreams/ambition, arrested development, and the transformative power of courage. Advance Wars: Days of Ruin features a struggle against utter desolation and themes of survival and humanity. Pokemon Black/White boldly introduces the themes of personal truths, personal choices, and a blended reality. Uncharted 2 plays with the theme of greed in the pursuit of treasure. Metroid Other M runs with themes of nature vs nurther and parenting roles. The Mario Galaxy series plays with the themes of loss, birth, and the forces that transend the universe.

In part 3 I’ll give more examples of video games that illustrate the facets of execution and discourse.

Story Design pt.3

by Richard Terrell

Continuing with examples for each facet of story design…

Pages from the DS game Ni No Kuni.

Execution

Efficiency. In general efficiency for video games is measured in both its narrative scenes and gameplay. To not confuse this facet with pacing, think along the lines of design space, art assets, and the number of elements of story content. If locations, set pieces, characters, scenes, etc. overlap in what they bring to the story, efficiency goes down. If you feel like a story begins to repeat its lessons, themes, or scenarios, consider if it could have gotten by with less. Tales of Symphonia is a game filled with many locations, characters, and scenarios that are very similar to each other both in their functional role (gameplay) and narrative role. Often in video games, a gameplay necessity will force a narrative inefficiency.

Coherence. The details of a story shouldn’t contradict each other. One of the most well known ways for video game narratives to lose coherence is from ludonarrative dissonance. Like with efficiency, we know that the story content communicated through the gameplay can influence and conflict with the story content presented otherwise. Because video games are designed with varying levels of abstractions dissonant elements are very likely to occur. For example,

in Final Fantasy 7, at the beginning of the game soldier shoot guns at the player characters. The damage dealt is only a small percentage of HP. Are we to believe that these guns are weak? These characters are armored? It’s hard to say. In fact, many video games characters survive from a range of cartoon violence. Though we accept these abstractions and interpretations, it’s hard to turn around and accept the death of a main character from a single bullet shot in a cutscene. These narrative bullets are even in games like Halo: Reach.

Pacing. For every wave, the climax is the result of building narrative and dramatic energy/tension. In terms of gameplay pacing, there should be a similar building of gameplay concepts or difficulty. And like the other facets of execution, we have to look at how the pacing of the story content and the gameplay match up. Might & Magic: Clash of Heroes features multiple chapters. In each, a new character is introduced starting at level 0. These chapters start out easy. As you progress you’ll fight stronger enemies and eventually a boss. As the overall story builds, the gameplay difficulty resets several times throughout the game. This disconnect is most apparent at the final chapter. Instead of launching into the final battle, you pick up yet another new character and are forced to play through a long gauntlet of relatively easy battles.

Style/Language. The story scenes in Super Smash Brothers Brawl: Subspace Emissary and Super Meat Boy are presented in the style of silent films (see Brawl videos here). No dialog or text.

Just visual storytelling. Final Fantasy 6 has a strong theater like presentation. Characters turn to the screen to emote opening up their bodies to us, the audience, via the screen. Each character is also introduced with their musical theme and a personalized description like you might find in a playbook. Other games borrow from the Japanese manga/anime style of storytelling featuring somewhat stilted dialog scenes that divulge lots of information. Examples include

the Advance Wars series, Tales of Symphonia, and The World Ends With You. And of course there are the games that go for a movie like cinematic presentation from Uncharted, Heavenly Sword, to Halo: Reach.

Medium. I presented many examples of games that take features from other mediums in part 1 of this series. Because video game designers can basically pick and choose the kinds of medium-specific elements they want to incorporate, there isn’t anything close to a singular scale of craft/design all video games are measured by. In other words, a modern game can feature voice acting or text based dialog. One isn’t necessarily better than the other. I have to say this because many believe cinematic presentation is the singular standard that all games should aspire to.

Dynamic. Some games feature branching narrative paths and encourage the player to explore all the possibilities like Radiant Historia, Tactics Ogre: Let Us Cling Together, The Legend of Zelda: Majora’s Mask, and Mass Effect. Some developers have discouraged exploring a game’s story possibilities like Heavy Rain. These are well known examples. But remember even the warps in the Super Mario Brothers platformers dynamically change up the progression of the

gameplay narrative. Along these lines most games wil have dynamic/emergent gameplay and therefore some level of dynamic narrative. So this category tends to refer to dynamic non-gameplay elements. Side quests are probably the easiest example of a dynamic ludonarrative feature.

Another image from Ni No Kuni.

Discourse

Creativity. All games are creative in one way or other whether we like the unique elements or not. It’s nice to compare how unique and creative one work is compared to others, however this is an inherently difficult task. No one plays all the games out there, not even of a single popular genre. And even if one were to play many games, one can always study a work more deeply to uncover more of its story content. So, if understanding how creative a work is depends on

how its details compare, you’re quest will never end. Still, as long as we properly scope our comments (based on series, genre, etc.), we can talk about creativity. This is especially easy to do when identifying video game parodies. Linear RPG, You Must Burn the Rope, and Super PSTW Action RPG are all great examples. These games aren’t very good gameplay and story wise if you don’t understand that they’re parodies. This guy didn’t quite understand, and now we have a hilariously entertaining video based on his response. In some ways, being a parody gives these games a freebie. Fortunately, they’re all short and to the point (efficient).

Series. The power of sequels and series is undeniable. In many mediums, narrative series and IP brands have significant selling power over new products. We love the familiar and we love knowing the full story. So, when games continue in a series many gamers enjoy connecting the details. Likewise, many gamers get very upset when they don’t line up. There are some that try to piece together the story of all the Zelda games even though they’re not intended to be a narrative series. Some argue over Metroid canonical content even including odd games like Metroid Prime Hunters and Metroid Pinball into the grand storyline. This facet is basically coherence across multiple independent stories.

Transmedia franchises. Halo is a popular video game series. The franchise also includes a collection of animated shorts, comics, and novels. There was even a rumored movie in the works.

All of these products work to support the detailed overarching Halo universe. Dead Space, Pokemon, Zelda, and Metroid are also transmedia franchises.

Resonance (Harmony)

Aligning a game’s narrative and gameplay is the most difficult and effective way for a video game to create resonance. Still, one can create resonance between any two facets of a story.

Typically, theme is more likely to resonate with each of the other facets. Because themes are so abstract, there more flexibility matching it up with concrete elements like setting, characters, and plot actions. I particularly appreciate the resonance between the poetry text presented in Braid and its gameplay. The poems tell the story of Tim’s past filled with love, loss, and longing. These abstract concepts resonate with the kinds of challenges and mechanics in the gameplay. For example, regret is paired with the idea of wanting to go back and fix things; a do over. In the gameplay players have the power to rewind time to fix things with few limitations. From here the richness of the resonance invites us to consider Tim’s character through his gameplay actions of solving puzzles. Is he wiser now? Can we ever really get a do over?

篇目2,5 Core Elements Of Interactive Storytelling

by Thomas Grip

Introduction

Over the past few years I have had a growing feeling that videogame storytelling is not what it could be. And the core issue is not in the writing, themes, characters or anything like that; instead, the main problem is with the overall delivery. There is always something that hinders me from truly feeling like I am playing a story. After pondering this on and off for quite some time I have come up with a list of five elements that I think are crucial to get the best kind of interactive narrative.

The following is my personal view on the subject, and is much more of a manifesto than an attempt at a rigorous scientific theory. That said, I do not think these are just some flimsy rules or the summary of a niche aesthetic. I truly believe that this is the best foundational framework to progress videogame storytelling and a summary of what most people would like out of an interactive narrative.

Also, it’s important to note that all of the elements below are needed. Drop one and the narrative experience will suffer.

With that out of the way, here goes:

1) Focus on Storytelling

This is a really simple point: the game must be, from the ground up, designed to tell a story. It must not be a game about puzzles, stacking gems or shooting moving targets. The game can contain all of these features, but they cannot be the core focus of the experience. The reason for the game to exist must be the wish to immerse the player inside a narrative; no other feature must take precedence over this.

The reason for this is pretty self-evident. A game that intends to deliver the best possible storytelling must of course focus on this. Several of the problems outlined below directly stem from this element not being taken seriously enough.

A key aspect to this element is that the story must be somewhat tangible. It must contain characters and settings that can be identified with and there must be some sort of drama. The game’s narrative cannot be extremely abstract, too simplistic or lack any interesting, story-related, happenings.

2) Most of the time is spent playing

Videogames are an interactive medium and therefore the bulk of the experience must involve some form of interaction. The core of the game should not be about reading or watching cutscenes, it should be about playing. This does not mean that there needs to be continual interaction; there is still room for downtime and it might even be crucial to not be playing constantly.

The above sounds pretty basic, almost a fundamental part of game design, but it is not that obvious. A common “wisdom” in game design is that choice is king, which Sid Meier’s quote “a game is a series of interesting choices” neatly encapsulate. However, I do not think this holds true at all for interactive storytelling. If choices were all that mattered, choose your own adventure books should be the ultimate interaction fiction – they are not. Most celebrated and narrative-focused videogames does not even have any story-related choices at all (The Last of Us is a recent example). Given this, is interaction really that important?

It sure is, but not for making choices. My view is that the main point of interaction in storytelling is to create a sense of presence, the feeling of being inside the game’s world. In order to achieve this, there needs to be a steady flow of active play. If the player remains inactive for longer periods, they will distance themselves from the experience. This is especially true during sections when players feel they ought to be in control. The game must always strive to maintain and strengthen experience of “being there”.

3) Interactions must make narrative sense

In order to claim that the player is immersed in a narrative, their actions must be somehow connected to the important happenings. The gameplay must not be of irrelevant, or even marginal, value to the story. There are two major reasons for this.

First, players must feel as though they are an active part of the story and not just an observer. If none of the important story moments include agency from the player, they become passive participants. If the gameplay is all about matching gems then it does not matter if players spends 99% of their time interacting; they are not part of any important happenings and their actions are thus irrelevant. Gameplay must be foundational to the narrative, not just a side activity while waiting for the next cutscene.

Second, players must be able to understand their role from their actions. If the player is supposed to be a detective, then this must be evident from the gameplay. A game that requires cutscenes or similar to explain the player’s part has failed to tell its story properly.

4) No repetitive actions

The core engagement from many games come from mastering a system. The longer time players spend with the game, the better they become at it. In order for this process to work, the player’s actions must be repeated over and over. But repetition is not something we want in a well formed story. Instead we want activities to only last as long as the pacing requires. The players are not playing to become good at some mechanics, they are playing to be part of an engrossing story. When an activity has played out its role, a game that wants to do proper storytelling must move on.

Another problem with repetition is that it breaks down the player’s imagination. Other media rely on the audience’s mind to fill out the blanks for a lot of the story’s occurrences. Movies and novels are vague enough to support these kinds of personal interpretations. But if the same actions are repeated over and over, the room for imagination becomes a lot slimmer. Players lose much of the ability to fill gaps and instead get a mechanical view of the narrative.

This does not mean that the core mechanics must constantly change, it just means that there must be variation on how they are used. Both Limbo and Braid are great examples of this. The basic gameplay can be learned in a minute, but the games still provide constant variation throughout the experience.

5) No major progression blocks

In order to keep players inside a narrative, their focus must constantly be on the story happenings. This does not rule out challenges, but it needs to be made sure that an obstacle never consumes all focus. It must be remembered that the players are playing in order to experience a story. If they get stuck at some point, focus fade away from the story, and is instead put on simply progressing. In turn, this leads to the unraveling of the game’s underlying mechanics and for players to try and optimize systems. Both of these are problems that can seriously degrade the narrative experience.

There are three common culprits for this: complex or obscure puzzles, mastery-demanding sections and maze-like environments. All of these are common in games and make it really easy for players to get stuck. Either by not being sure what to do next, or by not having the skills required to continue. Puzzles, mazes and skill-based challenges are not banned, but it is imperative to make sure that they do not hamper the experience. If some section is pulling players away from the story, it needs to go.

Games that do this

These five elements all sound pretty obvious. When writing the above I often felt I was pointing out things that were already widespread knowledge. But despite this, very few games incorporate all of the above. This quite astonishing when you think about it. The elements by themselves are quite common, but the combination of all is incredibly rare.

The best case for games of pure storytelling seems to be visual novels. But these all fail at element 2; they simply are not very interactive in nature and the player is mostly just a reader. They often also fails at element 3 as they do not give the player much actions related to the story (most are simply played out in a passive manner).

Action games like Last of Us and Bioshock infinite all fail on elements 4 and 5 (repetition and progression blocks). For larger portions of the game they often do not meet the requirements of element 3 (story related actions) either. It is also frequently the case that much of the story content is delivered in long cutscenes, which means that some do not even manage to fulfill element 2 (that most of the game is played). RPG:s do not fare much better as they often contain very repetitive elements. They often also have way too much downtime because of lengthy cutscenes and dialogue.

Games like Heavy Rain and The Walking Dead comes close to feeling like an interactive narrative, but fall flat at element 2. These games are basically just films with interactions slapped on to them. While interaction plays an integral part in the experience it cannot be said to be a driving force. Also, apart from a few instances the gameplay is all about reacting, it does have have the sort of deliberate planning that other games do. This removes a lot of the engagement that otherwise come naturally from videogames.

So what games do fulfill all of these elements? As the requirements of each element are not super specific, fulfillment depends on how one choose to evaluate. The one that I find comes closest is Thirty Flights of Loving, but it is slightly problematic because the narrative is so strange and fragmentary. Still, it is by far the game that comes closest to incorporating all elements. Another close one is To The Moon, but it relies way too much on dialog and cutscenes to meet the requirements. Gone Home is also pretty close to fulfilling the elements. However, your actions have little relevance to the core narrative and much of the game is spent reading rather than playing.

Whether one choose to see these games are fulfilling the requirements or not, I think they show the path forward. If we want to improve interactive storytelling, these are the sort of places to draw inspiration from. Also, I think it is quite telling that all of these games have gotten both critical and (as far as I know) commercial success. There is clearly a demand and appreciation for these sort of experiences.

Final Thoughts

It should be obvious, but I might as well say it: these elements say nothing of the quality of a game. One that meets none of the requirements can still be excellent, but it cannot claim to have fully playable, interactive storytelling as its main concern. Likewise, a game that fulfills all can still be crap. These elements just outline the foundation of a certain kind of experience. An experience that I think is almost non-existent in videogames today.

I hope that these five simple rules will be helpful for people to evaluate and structure their projects. The sort of videogames that can come out of this thinking is an open question as there is very little done so far. But the games that are close to having all these elements hint at a very wide range of experiences indeed. I have no doubts that this path will be very fruitful to explore.

Notes

Another important aspects of interaction that I left out is the ability to plan. I mention it a bit when discussing Walking Dead and Heavy Rain, but it is a worth digging into a little bit deeper. What we want from good gameplay interaction is not just that the player presses a lot of buttons. We want these actions to have some meaning for the future state of the game. When making an input players should be simulating in their minds how they see it turning out. Even if it just happens on a very short time span (eg “need to turn now to get a shot at the incoming asteroid”) it makes all the difference as now the player has adapted the input in way that never happens in a purely reactionary game.

The question of what is deemed repetitive is quite interesting to discuss. For instance, a game like Dear Esther only has the player walking or looking, which does not offer much variety. But since the scenery is constantly changing, few would call the game repetitive. Some games can also offer really complex and varied range of actions, but if the player is tasked to perform these constantly in similar situations, they quickly gets repetitive. I think is fair to say that repetition is mostly an asset problem. Making a non-repetitive game using limited asset counts is probably not possible. This also means that a proper storytelling game is bound to be asset heavy.

Here are some other games that I feel are close to fulfilling all elements: The Path,Journey, Everyday the Same Dream, Dinner Date, Imortall and Kentucky Route Zero. Whether they succeed or not is a bit up to interpretation, as all are a bit borderline. Still all of these are well worth one’s attention. This also concludes the list of all games I can think of that is have, or at least are closing to having, these five elements.

篇目3,Opinion: Once upon a time…

by Poya Manouchehri

[In this reprinted #altdevblogaday opinion piece, former Microsoft software design engineer Poya Manouchehri shares some advice for writing the story of your game.]

I have a theory: everyone has or will have, at some point, an idea for a story they want to write. Or tell. And I don’t mean a real life story, but a story that is a creation of one’s imagination.

Now it might be a passing thought… Maybe it’s a person, a news report, a real life event, a book, or a game that suddenly triggers an idea for a story. The process of turning that idea into something complete and finished is a whole other…well, story.

Currently I’m writing the story for the game Connectorium. It’ll be the second story I’m writing in full, after co-writing the Revival short film (I’m not counting the one or two short stories here and there, and a failed attempt at writing a fantasy novel after watching the first Lord of the Rings film. Who didn’t do that, right?).

Here are just a collection of random thoughts, observations, and experiences about the process. Obviously these are not the opinions of an expert; I’m merely hoping it opens up the way for a conversation and invites thoughts from you.

From abstraction to realization

This is something that is universal to the creative process. You begin with an empty canvas. Maybe a concept that is completely abstract and vague. Then with every sentence, with every stroke of a brush, with every added note, or with every line of code, you bring that abstraction one step closer to existence (and also the number of possibilities of what that end product will be reduces with every step).

But there is a key thing I have realized: this is a tw- way process. The original idea, or concept affects what you create. But what you create also affects the idea over time. To a point where the final product may in no way resemble the original idea. I think this a very important part of the creative process: the organic nature of it.

As far as a story goes, that initial concept and idea can be many different things. Maybe it’s a particular character, or a specific plot point. Maybe it’s a particular setting. Maybe it’s a mechanic in the game you are designing. Either way, it’s important to keep in mind that your completed story may be nothing like what you had initially conceived. And that’s OK. In fact it’s more than OK. It’s usually a good thing.

Working backwards

When I first started working on Connectorium, I had a general idea for the story. The game is about systems and connections, so the story was going to be about a little girl who wakes up one morning to a world where all connections have gone missing. Her adventure would be about her meeting various characters, helping them restore the missing connections, and solving the mystery.

For some time, though, I stalled fleshing out the story more. Eventually I asked myself, why am I wasting time? Why don’t I just write the story? And it occurred to me: it’s because I didn’t know how it’s going to end.

So one morning I decided to take my iPad, go to a quiet park, and not come back home until I figured out how the story will end. It took a couple of hours, but eventually I came up with an idea, quite suddenly really. I had a big smile on my face right at that moment, because I knew I could start writing the story now.

Maybe this is more a function of the kinds of story that I enjoy and like to write, but I find that I really need to know the ending early on. Everything in the plot, the characters, and the gameplay in the case of a game, is pushing the audience towards that ending. It’s what keeps the story coherent to me.

Characters or plot

One of my favorite writers, Isaac Asimov, is often criticized for having somewhat uninteresting and 2D characters. Nevertheless he is an amazing story teller.

But one can’t argue that the best of stories combine a great plot with believable and great characters. What I have noticed is that personally I’m much more interested and focused on the plot. So I always need to be conscious of the “flatness” of my characters.

For that reason, after I have written the initial draft of the story, I’ll do an iteration where I’ll focus specifically on each character, writing more back story, fixing the dialogue, descriptions, and so on, of course adjusting the plot where necessary. I can imagine the reverse can work just as well: building a detailed and interesting character, and developing the story around that character (or characters).

Dialogue, dialogue, dialogue

For me, probably the hardest part of writing a story is the dialogue. Not only is it really hard to write a believable, natural, and flowing conversation between two or more characters, it’s even harder to have all your characters not sound exactly the same! Exactly like…you!

More than anything, it just requires time, and rewrites to improve this. It is also important to have back stories for characters, even if none of it is ever revealed to the audience. Where do they come from? What do they do? What do they eat? What was their childhood like? What are their relationships like? What is their motivation? All of these impact how a character speaks, how they would react to a situation, and how they’d express themselves.

Another thing that has helped me is trying to picture a real life person acting out that character. Maybe someone you know, or an actor. Putting a face and voice to a line of dialog goes a long way to help you see if it’s the right fit. Sometimes reading it out loud in the voice that you think the character would be speaking in also helps here.

On the subject of games

I’ve been talking a lot about stories, and haven’t really talked much about games. Here is point I want to make which I can expect at least some to disagree with.

I feel that the gameplay must reinforce the story as much as possible. At the very least it shouldn’t contradict it, because that takes you out of the immersion that you might otherwise have. How often do you run around in a game, killing various things, and collecting numerous items, stats, etc, just to be reminded by a cutscene that you’re actually trying to resolve a much greater conflict.

And here is another (potentially less popular) thought. Given that there are practically infinite possible stories, why is it that a good percentage of games, especially those with plots and characters, include combat in some form as their core mechanic?

Is it that we are simply avoiding stories where combat isn’t an integral component? Or are we throwing in combat into the mix, regardless of whether or not it reinforces the story?

篇目4,Storytelling in Games: How to Write an Amazing Story Part I

by Winston

What’s up everyone! It’s my first post here, and today I’d like to shed light on perhaps the weakest area in gaming: and that’s the story.

Schools out there will teach you how to improve your grammar, spelling, vocabulary and how to write better stories by using adjectives, adverbs, metaphors, similes, alliteration… you name it. However, these skills you learn in high school translate very poorly into visual (film) and interactive media (games), sometimes even causing more harm than good. So unless you go to a highly touted university, you will never learn about the concepts that one should follow when creating a great story. And let me just say that one SHOULD follow these concepts, but not MUST. These are concepts after all, not rules.

Idea Generation

idea

There are two types of ways in which people come up with their story:

1. Through spontaneity (that idea that pops into your head).

2. Through brute force thinking (aka “staring at a blank piece of paper until drops of blood form on your forehead”).

What are the disadvantages and advantages of each one and which one should you use? Let’s talk about the first one first.

Spontaneity

Disadvantages: Ideas which come through spontaneity tend to be clichéd, cheesy, and lame. Not all the time, but if you rely on inspiration as the source of your ideas, you are essentially doing what most people out there are doing – coming up with obvious ideas which have been overdone. Be very selective about which ideas you choose to include in your story if they come through spontaneity.

Another disadvantage is that it will take a very long time to come up with a sufficient amount of ideas through spontaneity. Spontaneous moments can be quite rare, and those who rely on this approach will tend to procrastinate and eventually quit.

Advantages: Sometimes, you will be rewarded with an excellent idea for your story which could’ve only come through spontaneity. This idea adds great value to your story and you know how to recognise clichéd or boring ideas which you aren’t afraid to throw away. Other times, spontaneity can help you overcome ‘writer’s block.’

Now let’s discuss number two (brute force thinking) and why this should be the main method you use when writing stories.

Brute Force Thinking

There are two types of thinking which can be used: one of them is called convergent thinking and this is the type of thinking which mathematicians use. It basically means being able to come up with an answer to a problem. Convergent thinking certainly has it’s advantages in story writing, however, I am going to focus on the second type of brute force thinking. This is known as divergent thinking and it simply means ‘being able to think of multiple solutions to one problem.’

If you ever wondered why so few mathematicians, programmers or engineers are good at creativity, then there’s the reason. Their convergent thinking skills are highly developed, but they lack the practise for divergent thinking. There’s a myth that creativity comes from spontaneity and that you are either born as creative or not creative. This is far from the truth: psychologists have discovered that creative people are very good at divergent thinking. This is great news because divergent thinking can be improved through practice – like any other skill.

Disadvantages: It requires a LOT of brain work, practice and time to develop. Divergent thinkers often have to create an enormous amount of content and ideas, and they have to be very selective of which ones to include in their story (the rest of the content gets thrown away).

Let’s say you want to create a scene. As a divergent thinker, you’ll come up with at LEAST 5 different ways the scene can play out. Sometimes you come up with 10, 15, 20 different possible ways or even more and these have to be all written down, but only one of them gets selected to be included in the story. Imagine doing this for over 50 scenes, this process will get tiring fast and take a long time to complete.

Advantages: Despite this tiresome process of writing stories, the payoff is definitely worth it in the end, because, what you end up with is a unique and interesting story that can’t be found anywhere else. Your story won’t be clichéd because you’re doing the opposite of most writers out there and carefully selecting content which hasn’t been overused. You will also be able to work harder and procrastinate less, because you won’t have as many ‘blank mind’ moments (just make sure you minimize any other distractions).

So overall, your main idea generation method should come through divergent thinking, and not through spontaneity. However, when a brilliant idea manifests itself in your mind, then you should seize the opportunity and take it into consideration.

Storytelling 101: Show not tell

This same rule you learn in school still applies to movies and games. Whether you are trying to convey an idea, a theme or just exposition, it is wise to use visuals rather than words. You actually want to minimize the amount of dialogue and text as much as possible. How are some ways you can show that a female character secretly likes the main character? You can:

1. Tell the audience “She secretly likes you/him.” How lame is that? Some games do this though.

2. Make that female character expose her feelings towards the main character in a conversation with someone else.

3. Or perhaps… just perhaps… you can make that female character adjust her hair, or check her make up when she sees the main character coming.

The only time that narration or dialogue is required to out information is when:

1. There’s no other convenient way or

2. The dialogue is used in a natural setting

3. To save time (and speed up the pace of the story)

An example of having no convenient way to do show is the anime Death Note. The protagonist, Light Yagami is too clever for the audience to understand his complicated strategies, so they must be informed through narration (or dialogue of him explaining his plans to Ryuk). Now, here’s an example of horrible storytelling in which you should avoid at all costs. It’s from the game Persona 3 and 4.

Pretty much everything is explained through ‘telling’ in the Persona games. Take a look at these screenshots from the game, and you’ll know what I mean:

Does this look like a library to anyone? The text is completely pointless and a waste of time.

Persona 4 library

I have to shake my head when I see this next one. There is absolutely no need for this “you feel like you understand them more” crap.

persona 4 rise 2