分享《No Man’s Sky》开发过程

作者:Raffi Khatchadourian

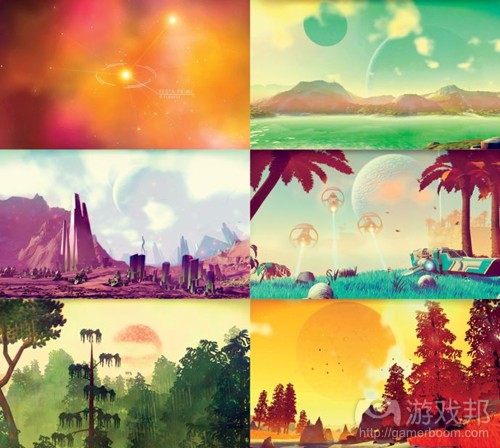

这个宇宙诞生在离伦敦有1个小时车程的Guildford镇上一个老式的2层楼建筑里。大概有12个人致力于创造它。他们坐在建筑一层的3排计算机终端前,主要是通过操作一行行代码,并创造决定虚拟行星年龄与排列的数学法则,小行星带,月亮与星球的聚集以及重力的物理学,轨道的痕迹,大气(雨,晴空和阴天)的密度和成分等等。宇宙中的星球将具有真实星球的规格,它们将通过数字空间的光年进行区分。它们的一小部分将支持复杂的生命。因为设计师是通过先建立其自然规律去创造他们的宇宙,而非手动创造各种未知的细节。他们计划在今年完成创造,那时候他们将会邀请无数人前来探索自己的作品—-名为《No Man’s Sky》的一款电子游戏。

游戏的首席架构师是一名34岁的计算机程序员Sean Murray。他又高又瘦,留着该修剪的胡子和头发;他总是穿着蓝色牛仔裤和格子衬衫。2006年,因为游戏开发质量问题,Murray离开了艺电,这家世界上最大的电子游戏制造商之一。他相信小团队的力量以及自己在种种约束中所想出的理念,2008年他和3个好友创建了名为Hello Games的小型公司(资金是来自他卖掉自己的房子的钱)。从那时起,他们的唯一产品便是一款名为《Joe Danger》的游戏,这是关于一个穷困潦倒的特技演员,他的主要技能便是骑着摩托车跳过障碍。在经历几次迭代后《Joe Danger》最终发行了,因为其可玩性以及幽默感而获得了一些名气。但它却不是完全成形的数字宇宙的前身。基于各种实用目的,《No Man’s Sku》将是无限的。玩家将从包含18446744073709551616个独特的星球的宇宙外源开始游戏。相比较而言,《侠盗猎车手:圣安地列斯》的游戏空间大概只有14平方英里。

在2013年年末的时候,Murray在Spike TV网上公开了他们为《No Man’s Sky》匆忙制作的一个预告片,希望能呈现出游戏大胆的一面。对于像《侠盗猎车手》那样带有较高预算的游戏(游戏邦注:即产业人士声称的AAA级游戏),“公开的预告片”通常会突出一些基于脚本且充满动作的片段去呈现出真正游戏场景。而他们自制的《No Man’s Sky》的预告片只有1分多钟的游戏内容:关于Murray探索一颗星球,先从水下开始,然后上船,飞进太空,并参与战斗。预告片中的镜头并未出现任何有关游戏玩法的内容,但是其图像却具有在游戏中鲜少看到的精致,Murray的旅行轨迹(从海洋到陆地再到天上)也暗示了前所未有的探索范围。

其他电子游戏开发者建议Murray不要发布预告片,他们担心这一预告片太含糊且非常规,Murray也就此考虑了好几天。但是Murray并不缺乏自信,他认为这些连续镜头能够唤醒观众在童年时的经历:凝望着星星并对太空到底长什么样充满好奇。所以他决定飞到洛杉矶并独自展示这一预告片。主要进行游戏配音编写的Joe Shrewsbury告诉我:“在我看来Sean是一个非常有野心的人。”认为自己是个内向的人的Murray表示工作室的灯让他感到害怕—-即为了保持另一个同事所谓的“神经质的人的特征”的低调。

在Spike TV上,Murray视线朝下,就好像紧闭双眼一般,但他同时也表现出了狂热粉丝般的热情。他说道:“这是一款大型游戏。我并不能真正做到公正。我们想要创造一款关于探索的游戏,我们想要创造一些真实的内容。”几乎所有电子游戏都是依赖于美术师所绘制的数字外墙,以此呈现出比现实更大的一个探索世界的幻影,但是《No Man’s Sky》中并不具有这种设置。Murray的预告片突出了在北极圈失事船只的场景,以及标志一个星系出现危险的巨大杀虫。他在节目上说道:“你在预告片中所看到的星球是位于遥远的地平线上,那是一个真实存在的地方。”那时候的Murray正与其他3个人致力于游戏中,但他告诉节目的主持人时他们都表示不敢相信。他补充道:“如果是在晚上,当你身处太空中时,你会看到星星,即那些真正的星星。它们周围环绕着一些星球,你可以前往那些星星并访问它们。”

当我今年年初在Murray的工作室第一次见到他时,他刚从位于加利福尼亚的索尼PlayStation总部回来。他与索尼之间具有深远的关系。在他公开《No Man’s Sky》的预告片前几天,他将预告片分发给一些产业人士,而索尼也立马表示对这一游戏的兴趣。索尼PlayStation的策略总监Shahid Ahmad告诉我:“我接二连三地给Sean发送了短信,告诉他,‘我们需要将游戏带到PlayStation上。请告诉我们你的要求。’”

2周后,也就是在圣诞前夜,泰晤士河的一条支流决堤并涌向了Hello Games工作室。Murray第一时间赶往了工作室但却发现笔记本电脑都飘在了水上;价值好几万美元的设备都毁于一旦了。虽然索尼能够提供给他们帮助,但Murray告诉我他并未开口要求资金援助。与好莱坞不同的是,电子游戏产业在高预算产品与独立产品之间具有巨大的鸿沟,他也从《Joe Danger》中了解到小型工作室总是会受限于分销商。所以他最终只选择让索尼帮助他们为《No Man’s Sky》在E3上争取一个位置。之前从未有任何独立开发游戏出现在主舞台上,但就像他所说的那样:“我说(这真的很自大)‘我们想要主导E3’。他们虽然认为‘这是不可能的事,’但我们会努力争取的。我们以在舞台上为他们工作作为交易。”

索尼表示同意并决定提供资源去推广《No Man’s Sky》—-这是他们对于一款来自小型工作室的未完成作品所作出的绝无仅有的帮助。现在的电子游戏产业正在与好莱坞展开竞争;根据估算,去年它便创造了超过800亿美元的收益,AAA级游戏的市场营销预算也足以和那些大型电影相匹敌。所以从索尼为《No Man’s Sky》所指定的市场营销策略看来,他们希望游戏能够赚到数亿美元的收益;今年索尼将与自己的一些游戏(游戏邦注:包括最新的《蝙蝠侠》游戏)一起去推广这款游戏。索尼PlayStation的副总裁Adam Boyes是这么描述这款游戏的:“这是我们产业历史上最大的游戏之一。”

现在Murray所需要做的事便是递交游戏。去年,当一个记者问他游戏何时会准备好时,他的回答是:“作为一支非常小型的团队,我们所创造的是一款充满野心的游戏,而我们将做的事是告诉人们游戏何时会诞生,也许这一答案会让大家感到失望。”而索尼的参与意味着游戏的最终发行时间将更加明确,但《No Man’s Sky》并不是一款能够随便赶工的项目。因为它的算式结构,几乎游戏中的所有内容都是相通的:船只操作的改变可能会影响昆虫的飞行。宇宙的开发必须是全面进行的;有时候我们还必须对其进行拆解,然后再重新组装。在我到达前Murray便曾警告我:“游戏是位于操纵台上,所以你将只会看到它们的零部件。其它游戏可能会因为一些特别有趣的关卡而受益,但是我们的游戏并不是这样的。”之前他所呈现的关于《No Man’s Sku》的架构包含了一些精心设计的元素。一些基于光年而区分的功能被更紧密地维系在一起;动物也被聚集在了一起如此它们便能够一起出现。天气的转变将遵循大气变化的节奏,从而确保它们能够出现在演示版本期间。让我们想象在几分钟内于地球上传达生命:这是需要采取捷径的。

我们待在重新装修过的工作室二楼的休息室中;概念创作图挂在贴满便利贴的白板旁。房间摆满了明亮简单的宜家家具。我们坐在平板电视前,Murray加载了他为E3制作的游戏演示版本:6颗星球组成的1个太阳系。希望能够保持游戏的发现感,他并未明确呈现出如何游戏,但也分享了一些细节。每个玩家会从银河的周边的随机选择的一颗星球开始游戏。他们的目标是朝着中心位置前进,去揭开真正的奥秘,而对于玩家如何做以及他们是否会选择这么做都是明确的。人们可以通过开矿,贸易,打斗或探索做到这点。随着星球被发现,有关这些星球的信息(包括他们的发现在的名字)便会出现在银河地图上并在网上更新出来。但是因为游戏接近无限的规格,玩家很少会遇到彼此。当他们朝中心位置前行时,游戏会变得越来越困难,世界(包括地形,动物群和植物群)也会变得越发超现实。

坐在休息室的我们是从一个名为Oria V的星球开始。Murray会在演示版本期间紧张地徘徊着。他说道:“我会四处走来走去,然后让你握着控制器一会。”我看着他穿过一片橙草区,经过了蓝绿色的蕨类植物和靛蓝色的灌木丛,直到居住着恐龙和羚羊的一片咸水湖。在花了5分钟经过3个星球后,他将控制器递给了我,并将我留在色彩绚丽的梦幻景象中,在干旱的土地上分散着一些晶体和蓝宝石。在植物群中,红杉的高处不断摇摆着,就像海藻一般。我好奇地穿越了丘陵并走向带有熔岩颜色的海洋。海洋中并不存在生命。当我按压按键时,我便激活了一个喷气背包并创造了空气。雾气弥漫在海洋上,Murray指向了遥远的悬崖上的模糊轮廓。他说道:“那里好像有一些洞穴。”于是我便朝他们继续前进。《No Man’s Sky》的宇宙是由理想的荒野所组成的,所以洞穴与任何真正的洞穴是一样的。我爬进了其中的一个洞穴,Murray说道:“让我们看看它有多大。”

洞穴的内部是由蓝色,绿色,紫色和棕色所组成,里面的光线非常温暖。一些发光物体(好像没有生命的萤火虫)充斥在空气中。AAA级游戏通常都是以较为凝重的色彩为主,但是Murray却更喜欢生动多彩的图像。他告诉我:“我认为《No Man’s Sky》能够引起人们共鸣的一个原因便是因为它是多彩的。”

这款游戏是对于Murray从小所热爱的科幻小说(即Asimov,Clarke和Heinlein的作品)的致敬。在20世纪70年代到80年代期间,科幻小说的封面通常都与书里的故事没有太大联系;有时候它们甚至是相互独立的。对于一个富有想象力的青少年来说,通过历史和戏剧去灌输想象力是特别有趣的事。太空是一个浪漫的前沿,是广阔宇宙的最高点。危险是探索的产物:火箭会坠毁在贫瘠的小行星上;还有消失的文明背后所隐藏的秘密。Murray说道:“但是从内在看来正在发生的一切都是乐观的。当你了解它并继续向前走时,你会想要成为这样的人—-这真的很让人兴奋。然而这时候很多科幻都是反乌托邦的。那么我该如何处理这一问题?”

《No Man’s Sky》的参考对象可能是折扣店小说,但是游戏也引入了怀旧感和更加复杂的风格。纽约大学的游戏中心负责人Frank Lantz告诉我:“很多电子游戏所遗漏的一点是表现出风格的自信感。而《No Man’s Sky》便非常有个性。”

我靠近了海边的一个洞穴,Murray指了指数字地质的一部分。他说道:“我之前从未看到这个。”然后他拿走了控制器进行更仔细的观察。Murray的主要代码贡献是在行星地形方面,它为这些构成创造了特殊的价值。在进行一定的探索后,他说道:“对不起,你可以拿回控制器了。”

从洞穴内部,我看到海岸边的一座山脊。我问道:“如果我跳下来的话会怎样?”

他说道:“你会没事的。我们并不想你摔断腿或胳膊。这只是一种探索。我们不希望玩家感到紧张。”

每个星球都有独特的生物群落。在一颗星球上,我们遇到了带有球根状头部且看起来很友好的鲸鱼混种。而在另外一个星球,经过烤制的盐被嵌入红色珊瑚中;一颗星球漂浮在空中,停悬的机器人穿越了地平线。Murray说道:“那些是无人飞机。如果它们发现你杀死了动物或非法采集资源,它们便会攻击你。”在一颗草绿色的星球上,长着斑马腿的天真的羚羊会在我们四周奔跑着。当我走到一个被树木遮挡着的沟壑时,薄雾便会出现。Murray说:“这是之前没人看过的地方。”生物群落在光亮和颜色上和地球的物种是一样的。当我继续向下,沟壑将会不断变深直至岩石的某一边成形。尽管这件作品处于半完成状态,但是游戏世界却非常吸引人。Murray说道:“我很抱歉在这颗星球中还不存在游戏玩法元素。”在发现许多需要改善的地方之前,游戏整体可能会比我所看到的更糟糕。他说道:“你可能会忘记它曾经是这样的。”

这个版本的游戏是对于公众承诺的暗示:即Murray在E3上的展示,在展会上他站在一个巨大的舞台上并在一个19英寸的屏幕上播放着《No Man’s Sky》的图像。他告诉我:“有5000多名观众,这还不包括在家收看的(至少)5百万观众。”与Murray一起待在后台的工作室程序员之一回想了当时的场景并说道:“Sean的脸越来越苍白,他真的非常紧张。”为了克服这种情绪,Murray一直让自己专注于游戏故事,即从工作室的起源说起。他告诉我:“当我走出后台时,我差点哭了出来,因为我将要讲述的折扣游戏是我一直都想要创造的内容。”

Murray的童年记忆是来自澳大利亚布里斯班的一个甘蔗农场。他出生在爱尔兰,但在2岁的时候他的父母选择移民到澳大利亚。他告诉我:“我住在一间华丽的小屋里,它是架在支撑物之上,它还有一个波纹型的铁屋顶。”2年后,Murray的父母为了昆士兰州几百万英亩的农场而再次搬家。他们的新家就像是一个外星人前哨,有着自己发电的系统,还有抽水机。总会有些长途旅行中的路人前来拜访。有时候沙尘暴会席卷这片干燥的土地。单单穿越这片区域就如探险一般。Murray说道:“你会出门检查风车等是否有效运行着。你需要与另一个人结伴出门。大人们总是会告诉小孩,如果与你同行的人发生了意外,你就需要寻找避难处,如果找不到的话那就不要找了。因为即使没有水和食物你也能够撑过3天,所以你只需要做一件事:收集木头去燃火。你需要待在同一个地方,并在特定时间点燃火焰。这是一个计划:我将搭乘飞机并在三天内搜索整片区域。”Murray经常抱怨父亲总是进行多天的长途跋涉。晚上的时候他们会在布满星星的天空下搭起帐篷,伴着宇宙入睡。

正是在那里,Murray渐渐迷上了科幻小说。当他第一次看到《沙丘》时,他说道:“我甚至还记得当时迫切想看到它的心情,简直达到了废寝忘食。”在几年后,当他组建Hello Games时,他告诉联合创始人,即名为Ryan Doyle和David Ream两名程序员以及名为Grant Duncan的美术师将他们的童年作为游戏的原材料。“我告诉他们,‘回想你还是孩子的时候。你想要成为谁?是牛仔,还是宇航员,是特技演员还是消防员,或者是警察等等。;”待在Murray的起居室,这四个人首次将注意力转向那些基本内容,并编写软件去决定对象在理论游戏空间中的表现。Duncan告诉我:“我们经常提到皮克斯,因为他们的作品都很多彩但却不会幼稚。”《Joe Danger》的灵感便是来自Duncan在一盒老玩具中找到的一个特技人玩偶。

这几个合作伙伴一起共事了好几年,并且经历了将近破产的情况。Murray告诉我:“我卖掉了自己的PS3。除了一些必需品外我们卖掉了所有的东西。”为了庆祝2010年6月的发行,Murray买了几瓶廉价的苹果酒。Murray说道:“我们决定喝些苹果酒,游戏将问世了,并且该履行它的指责了。”直到午夜之后游戏才出现在了英国的网上。当它首次加载时,屏幕是黑色的,这引起了暂时的恐慌。但在短短的1个小时内,这四个人便赚回了本。

在那两年之后的一个早上,即在与微软关于《Joe Danger》续集进行艰难的市场营销协商后,Murray开始进行《No Man’s Sky》。他回忆道:“那时候其他人都还在家。我自己一个人待在工作室里,并开始编写代码。那时候的我非常兴奋,一直工作到凌晨三点。现在回想起来就觉得自己好像遭遇了中年职业危机一样。这些游戏的要点是什么呢?就像《Joe Danger》—-它有怎样的影响力?”Murray和他的联合创始人曾开玩笑说终有一天他们要创造出一款野心勃勃的游戏,即他们所谓的“摩天大楼项目”。隔天,他对Duncan和Ream说:“我们来做吧!”他创造了一小块地形样本,其实根本看不出来是什么,Ream告诉我:“那真的非常抽象,我们都在想,你到底在做什么?”Duncan对此充满怀疑。他所认识的美术师都对Murray所使用的技术不屑一顾;甚至还有人警告他“那就像垃圾一样。”

Duncan和Ream开始设计一款相对传统的游戏,即以《Joe Danger》为模型—-去呈现出他们孩童时的另一个梦想职业。他们将游戏命名为《Space Cadets》。但Murray劝他们去考虑一个更开放的项目。他告诉我:“我有这种感觉:我想要创建一家新公司,即走一条与Hello Games不同的道路。”他将公司分成了2部分,在接下来几个月时间里这三个人连同程序员Hazel McKendrick共同待在一个房间里秘密地开发《No Man’s Sky》。

为了创造一款AAA级游戏,无数美术师和程序员展开了紧密的合作:《侠盗猎车手》的游戏空间中几乎每一个像素都凝聚了制作者的用心。Murray很早就意识到小团队要想创造一款能够与之相抗衡的游戏的唯一办法便是使用程序生成内容,即处理随机数字字符串的方程式所创造的数字环境。这一方法被用于1984年Murray所玩过的一款名为《Elite》的太空游戏。Georgia Tech的娱乐智能实验室负责人Mark Riedl告诉我:“那时候的游戏拥有许多程序生成内容,因为当时计算机内存真的很小;虽然这种方法暂时被遗忘了,但是现在人们重新记起来了。”基于程序生成内容的游戏总是很相似,即都是基于容易被发现的算式模式,或者是带有混乱的视觉效果。但是Murray希望如果能够达成妥协,他便能够创造出值得发现的更丰富的环境—-这是带有现实性的探索内容的科幻版本。

当Murray决定了游戏的基本数学架构时,它需要一些随机数字去填充它。没有一台计算机能够生成真正的随机内容,但程序员可以使用各种算法,有时候也可以利用机器的物理限制去创造近似值。Murray告诉我:“计算机只能理解一组大小的数字。当你在创造一台计算机时,你可能会说,数字将被储存在这里,这是关于多少数字能够存放的空间。”对于一台游戏主机,存放空间是64位体。当玩家首次进入《No Man’s Sky》时,一个“种子”数字将被插入等式中,以生成较长的数字字符串,当计算机尝试着将其储存在64位体的空间时,它们会被任意删节掉。Murray说道:“你将只留下一个随机数字。”种子是指银行的整体结构,而源自这里的随机数字将作为星星的数字标记。之后这一过程将被重复进行:每个星星的数字将变成定义其轨道星球的种子,而星球数字将作为种子去定义星球地形,大气和生态的性质。基于这种方式,系统将包含平均信息量和结构:如果两个玩家从同一个种子和同样的公式开始游戏,他们将经历同样的环境。

设计需要顾及到计算机处理中特别的经济:从仅有的1400行代码中呈现出的18万亿个独特星球的地形。因为游戏中所有必要的视觉信息都是通过公式描绘出来,它们在遇到玩家前都不需要经过图像渲染。Murray将这一处理过程与正玄曲线进行比较:一次方程式能够定义一个无限的山丘和山谷的周线—-周线上的每个点都将独立于其它点。他说道:“这是非常有趣的事。这意味着我不需要估算一个点之前和之后的任何事物。”基于同样的方式,游戏将持续识别玩家的位置,然后只渲染他们看得见的东西。当玩家离开山,羚羊或星系时,它们将像出现时那般快速消失。Murray说道:“你可以基于哲理去了解它。在你访问一颗星球前它是否存在?在算式将其创造出来前它们都是不存在的。”

最初,系统被证实是非常难以控制的。它生成了非常荒芜像是外星球一般,同时也是难以穿越的星球地形。如果Murray将系统推向其它方向,地形将变得更加枯燥且不断重复。同时还存在一些特定的自然功能,如河流,但是它们并不能轻松地以等式呈现出来。为了在一款传统游戏中创造河流,美术师需要创造一座山,并在山上放置数字水流,然后向下映射水的流动轨道。Murray告诉我:“这是一种正确的方式。”但是处理过程包括一系列艰苦的计算,并且需要事先了解地势。因为《No Man’s Sky》的算式结构(游戏邦注:实时渲染每一个像素),所以开发者只能在遇到的时候才能了解相关地形。从理论上来看,游戏可以在决定河流的特定像素前快速渲染一个地形样本,但之后它同时也要渲染样本周围的地形样本。Murray说道:“最终情况便是我们将调用一个只存在一种靠强力攻击解决方法才能够克服的困难问题。如果不计算所有内容的话我们便不知道还有什么方法。”在经过反复试验后,他建议采取一种数学方法去解决问题。

在每天早上10点左右,Murray都会与团队进行一次简短的会议。程序员和美术师会站在一排排计算机之间。在快速陈述后他们便能够识别出问题并明确目标;晚上他们的工作将进入主创建阶段。Murray将轻松并且谨慎地分配任务。

在我进行访问期间,4名美术师列出了他们的计划,然后便着手开始工作。美术师想出了程序员算法的原型。其中1名美术师花了1天时间去创造昆虫:在Pinterest上搜索图像,为昆虫原型设计功能,研究算法是如何在无数排列中转变原型,然后做出调整。艺术总监Grant Duncan告诉我:“这是一个不断迭代与优化的过程。”他一整天都致力于能够以各种方式结合在一起的结构模块中。因为小小的改变都可能具有不可预知的影响—–一棵植物的颜色就可能影响到星球上的每一棵树木,石头和动物。他的团队使用了算式“drone(游戏邦注:网络游戏中的一种虚拟生物,由孵化场的幼虫进化而来,体内包含着一组遗传密码,可以变形进化成任何一种大型的虫族‘建筑’)”去导航宇宙,并使用快照去衡量决策的作用。有时候Duncan会停下工作去提供建议。在审查一些昆虫时他说道:“除了颜色外,这些形状是可行的,但是其它都很奇怪。”

Murray与David Ream一起坐了下来,后者的主要工作是编写游戏系统代码。Ream一直致力于让飞船在战斗中的表现更加真实,他希望Murray能够测试自己的工作。Ream说道:“我将控制器递给Sean,因为我非常了解所有数字,所以我总是会自然地使用正确的方式去玩游戏。并且因为我们间的关系非常好,所以我可以轻松地和Sean进行讨论。”

Murray玩了几分钟,一直在与敌人的飞船厮杀。他说道:“这比我在周日玩的更有趣了。”但他也担心过度的现实性是否会让那些不熟悉太空中无摩擦的运动的玩家感到困惑。他建议Ream做出一些调整。在测试期间,Murray注意到他的飞船太快进入星球的大气层,这与他在E3中所呈现的不一样。他说道:“我们丢失了过去所存在的一些内容。现在的速度会让人感到诧异。”

Hazel McKendrick走过来并说道:“大气层并不是很厚。”她刚刚调整了公式去提供更加自然的阳光效应,并让星球周边的视野变得更好。为了重新创造之前的那种感觉,她建议在飞船经过时人为提高大气层的厚度。

在一整天时间里,其他团队成员都致力于阴影,生物的人工智能,“碰撞”对象或物理性等等工作。在程序员提高了树与石头的碰撞后,它们能够被粉碎了;他射击了山坡,并导致石头坠落下来,相互撞击。星球的天体也出现了一些特有的问题;在传统电子游戏中,数字太空通常都是扁平的。在重力得到标准化以前,物体有时候会从星球上滑落。其中1名程序员Charlie Tangora列举了一种母牛般的生物去描述这一问题,即该生物能够在洞穴顶端行走;在意识到问题之前这是需要花些时间进行审核的内容。就像“你现在处于南半球,而所有的一切都是颠倒过来一样。”

在Murray离开电脑前,他一直致力于地形中。他告我自己总是在寻找更多理念。去年他看了《星际穿越》这部电影,其中有些场景是出现在一个漫天冰雪且没有生命迹象的星球,这里“拥有一些非常完美的‘数学般的’地形。”于是隔天他便写出了能够创造同样的冰原的公式。最近,他注意到了一位美术师为另一款电子游戏所创造的地质构造,并意识到《No Man’s Sky》的算法不能算出它们。这一问题一直困扰着他,直至他发现一个等式,即比利时植物遗传学家Johan Gielis在2003年所公布的内容。这个简单的等式能够描述大量的自然形式,包括贵藻类,海星,蛛网,贝壳,雪花,水晶等等。甚至连Gielis自己在将其整合到模拟软件时也大吃一惊。他说道:“所有的这些美力的形状就这么呈现出来。这真的太不真实了。我花了2年的时间在思考自己到底哪里出错,为什么没有人能够发现它?”Gielis将这一等式命名为Superformula。

Murray坐在监视器前将Superformula敲打进一个测试星球的地形中。他创造了一个核桃形状的物体并漂浮在沙漠上方的无限网格中。这幅图像就像是一张20世纪80年代的唱片封面,但从这里看这并不是要点。不管何时当他刷新渲染,漂浮的形状都会发生改变。很多内容都是不对称的。游戏设计师参考了几行代码,它们需要许多“昂贵的”处理时间。而Superformula非常廉价。

在工作的同时他告诉我:“对于我们来说最困难的事之一便是创造一致的形状。”为了创造不一样的风景,公式必须能够处理大范围的随机信息,并且不能生成会引起问题的数字异常。他说道:“这听起来很可笑,但我们很难找到能够依赖的公式。”Superformula是值得信赖的。他指着一块突出的岩石,这看起来就像是遭遇侵蚀的沙漠地形。他说道:“这是非常自然的。”他添加了更多内容到公式中,转动了它所创造的形状,并尝试了不同规格,将其埋藏在星球的表面之下。他设想在整款游戏中使用Superformula,特别是在银河中心位置,即风景会变得更加超现实。基于较小的参数改变,等式将创造出让人激动的可变性。在一次渲染中,它创造出了起伏的群山。Murray刷新了页面:出现了一个星星状的岩层。他看起来很兴奋。他说道:“这标志着当我点击按键时,屏幕上便会出现让人兴奋的画面。”

对于未知的好奇有可能分散游戏创造者的注意力。某一刻我坐在Duncan身边,他正专注于一个带有外来真菌的测试星球。他告诉我:“我正尝试着创造一些更奇怪的植物。”鸟儿飞过高耸的黑色尖塔—-这是受到英国插画师John Harris所启发的太空建筑。Duncan激活了鸟的算法,但奇怪的是食草类恐龙也同样被激活了。他说道:“我是为了测试才创造了这个世界,之前我从未在这里遇到过动物。我不知道接下来会怎样。”恐龙逃跑了。几分钟后我询问了他正在研究的真菌的属性。他害羞地说道:“我只是在探索。有时候我甚至会问自己,我到底在做什么。我应该只是在工作。”

到5月的时候,这支团队变得更加努力地工作。Murray的头发和胡须变得更长了。与索尼的讨论也变得更复杂;该公司指望《No Man’s Sky》将会是一款反类型的热门游戏,而其市场营销者开始考虑采取不同方式去推广它,游戏故事也开始脱离他的控制。Murray告诉我,他总是失眠。他说道:“我最大的担忧是,我们会因为各种势头而不是自己的意愿最终发行游戏。”因为游戏的范围,也因为他已经决定不公开一些主要功能,他害怕游戏变成Rorschach的试验品,即每个潜在玩家所期待看到的内容都不存在于游戏中。《Elite》的其中一位创造者David Braben在我询问他有关游戏的看法时说道:“炒作是一项艰难的任务。”

甚至当一个与Superformula一样简单的功能被写进地形生成系统时也引起了一些并发症。我询问了Murray它是如何运行的,他告诉我:“尽管它现在会损害生物AI,但是它真的很酷。”他花了许多时间去编写代码,但是却很难阻止分心事物的打扰。

索尼希望能够发行一本指南手册,而当Murray意识到这是必然的,他便决定参与其中。某天下午,他见了《守望者》漫画系列的联合创始人Dave Gibbons,以讨论他作为编者的角色。在楼上的休息室中,他们讨论了Philip K. Dick以及Murray很喜欢的科幻小说《Terran Trade Authority》。然后Murray转向平板电视并将只有漫天雪地的高山的星球呈现给Gibbons。他说道:“这是一个逼真的宇宙。我可以朝任何方向走好几天,我最终将走遍整个星球并回到开始的地方。”

Gibbons说道:“所以你可以真正探索一颗星球并将其绘制出来。”

Murray说道:“对于有些人,这便是他们会做的所有事,他们将拥有一款很好看的游戏。”他登上飞船并飞过一个小行星带。“我们并未公开但却是我认为很酷的内容是,如果我按压一个按键,我便可以跳到一张银河地图上。”然后他便按压了一个按键,然后整个太空都缩成了一个光点,即代表太阳系。

银河地图能够通过在一个白色的正方形中绘制一个近似的太阳而提供飞船的位置。文本标注了太阳系的计算机生成名,即Ethaedair;一张矢量图指示了飞船的超光速推进器能够触及的星星。Murray说道:“这之前就在游戏中了,但它一直都是一种假设。通常情况下它只是某些人所创造的一张图,存在两个你可以来回走动的小关卡,或出现在模拟‘太阳系’上的十个关卡。”这就像是为了赢得掌声而卖力表演的魔术师。他操纵着控制器,整个太空都围绕着Ethaedair的太阳旋转着。星星和发光的宇宙形成一个圆弧;这就像是突然展现出自己完整深度的一个2维体。Gibbons发出了赞叹,Murray开始更轻柔地进行描述:“如果我往回拉一点,你便会感受到我们所创造的内容的大小。”无数星星将从你身边略过。Gibbons轻轻地笑了下,并说道:“这就像是一大盒巧克力一样。”

Murray说道:“也许我应该更快地前进。太空的光年是以一种极可怕的速度展开。这也许不是真正的宇宙,但却呈现出了一种非常棒的现实:系统庞大的数学运算。Murray转向了发光的球体。他说道:”这便是中心。“这一游戏版本让Murray能够跳到他想到达的任何太阳系,但是为了创造悬念,他进入了更深的银河地图的3维空间。“这一架构被整合在一起,所以我便可以创造一个演示版本并将其呈现在人们面前。我有点害怕,因为当我按压这个按键时,我并不知道我们会看到什么—-这也是结束一个演示版本的奇怪方式。可能某些环节会出错。或者我们会看到一个很无聊的星球。但现在我必须这么走下去,因为即使无聊它也是一颗全新的星球。”

Gibbons说道:“就像它是真正存在的一样,对吧?”

Murray停在一个星团上并感叹了它的密度。最终他克服了犹豫不决的想法并选择了一个目的地。他说道:“我不敢保证这是否是有趣的。”地图消失了。他回到了驾驶舱中并启动了超光速推进装置。然后所有的空间开始变得模糊,飞船以极快的速度驶向了未知领域。

(本文为游戏邦/gamerboom.com编译,拒绝任何不保留版权的转发,如需转载请联系:游戏邦)

WORLD WITHOUT END

BY RAFFI KHATCHADOURIAN

The universe is being built in an old two-story building, in the town of Guildford, half an hour by train from London. About a dozen people are working on it. They sit at computer terminals in three rows on the building’s first floor and, primarily by manipulating lines of code, they make mathematical rules that will determine the age and arrangement of virtual stars, the clustering of asteroid belts and moons and planets, the physics of gravity, the arc of orbits, the density and composition of atmospheres—rain, clear skies, overcast. Planets in the universe will be the size of real planets, and they will be separated from one another by light-years of digital space. A small fraction of them will support complex life. Because the designers are building their universe by establishing its laws of nature, rather than by hand-crafting its details, much about it remains unknown, even to them. They are scheduled to finish at the end of this year; at that time, they will invite millions of people to explore their creation, as a video game, packaged under the title No Man’s Sky.

The game’s chief architect is a thirty-four-year-old computer programmer named Sean Murray. He is tall and thin, with a beard and hair that he allows to wander beyond the boundaries of a trim; his uniform is a pair of bluejeans and a plaid shirt. In 2006, frustrated by the impersonal quality of corporate game development, Murray left a successful career with Electronic Arts, one of the largest manufacturers of video games in the world. He believes in small teams and in the idea that creativity emerges from constraint, and so, in 2008, he and three friends founded a tiny company called Hello Games, using money he raised by selling his home. Since then, its sole product has been a game called Joe Danger, about a down-and-out stuntman whose primary skill is jumping over stuff with a motorcycle. Joe Danger, released in several iterations, earned a reputation for playability and humor. (In one version, it is possible to perform stunts as a cupcake riding a bike.) But it was hardly the obvious predecessor to a fully formed digital cosmos. No Man’s Sky will, for all practical purposes, be infinite. Players will begin at the outer edges of a galaxy containing 18,446,744,073,709,551,616 unique planets. By comparison, the game space of Grand Theft Auto: San Andreas appears to be about fourteen square miles.

From the moment Murray unveiled a hastily built trailer for No Man’s Sky, in late 2013, on the Spike TV network, anticipation for the game has taken on an aspect of delirium. For a big-budget franchise like Grand Theft Auto—what people in the industry call a triple-A game—an “announcement trailer” typically features carefully scripted, action-filled vignettes that present a simulacrum of actual play. The No Man’s Sky trailer, which was homemade, featured a minute or so of the actual game: a recording of Murray exploring a planet, beginning undersea, then boarding a ship, flying into space, and engaging in combat. The footage communicated nothing concrete about the game play, but the graphics were rendered with an artistic finesse rarely seen in games, and the arc of Murray’s journey—the unbroken sweep from ocean to land to heavens—implied an unprecedented range of possible discovery.

Other video-game developers advised Murray not to release the trailer, fearing that it was too vague and unconventional, and for days he deliberated. But Murray is not short on self-assurance, and he believed that the footage evoked a near-universal childhood experience: gazing up at the stars and wondering what space might be like. He decided to fly to Los Angeles and present the trailer himself, on the air. “Sean strikes me as incredibly driven and ambitious, but he is also polite and sweet about it,” Joe Shrewsbury, whose band, 65daysofstatic, is writing the game’s soundtrack, told me. Murray, who describes himself as an introvert, says that studio lights terrify him—in keeping with a habit of self-effacement that another colleague described as “the nervous-guy shtick.”

On the Spike TV set, Murray looked downward, as if shielding his eyes, but he also projected fanboy enthusiasm. “It is a huge game,” he said. “I can’t really do it justice. We wanted to make a game about exploration, and we wanted to make something that was real.” Nearly all video games rely on digital facades, drawn by artists, to give the illusion of an explorable world that is far larger than it really is, but No Man’s Sky will contain no such contrivance. Murray’s trailer featured luxuriant scenes of crashed ships on arctic terrain, giant sandworms—a galaxy of exotic dangers. “That planet on the horizon, which you see on the trailer, that’s a real place,” he said on the set. At the time, Murray was working on the game with only three other people, and when he told the show’s hosts they reacted incredulously. “If it is nighttime, and you are in space, and you see stars, those are real stars,” he added. “Those are suns, and they have planets around them—and you can go and visit them.”

When I first met with Murray, at his studio, earlier this year, he had just flown back from the North American headquarters of Sony PlayStation, in California. He had a long relationship with Sony. A few days before he unveiled the No Man’s Sky trailer, in 2013, he had distributed versions of it to people in the industry, and Sony had been immediately interested. “I sent Sean a barrage of texts,” Shahid Ahmad, a director of strategic content at Sony PlayStation, told me. “I said, ‘We need to get this on PlayStation. Tell me what you need.’ ”

Two weeks later, on Christmas Eve, a tributary of the Thames overflowed in Guildford, flooding the Hello Games studio. Murray rushed over and found laptops floating in waist-deep water; tens of thousands of dollars’ worth of equipment was destroyed. Sony’s offer of assistance remained, but Murray told me that he did not ask for funding. Unlike Hollywood, the video-game industry is marked by a vast chasm between big-budget productions and independent ones, and he had learned with Joe Danger that a small studio could easily become beholden to a distributor. Instead, he requested Sony’s help in securing a place for No Man’s Sky at the Electronic Entertainment Expo, or E3, the largest gaming trade show in America. No independently produced title had ever been featured on the main stage, but, as he recalled, “I said—and this was really cocky—‘We want to own E3.’ They were, like, ‘That’s not going to happen,’ but we pushed for it. We traded working for them for being onstage.” (Ahmad told me that the hesitation was largely logistical: “E3 takes time to plan.”)

Sony agreed, and also decided to throw its resources into promoting No Man’s Sky as a top title—an unprecedented gesture for an unfinished product by a tiny studio. The video-game industry now rivals Hollywood; by one estimate, it generated more than eighty billion dollars in revenue last year, and marketing budgets for triple-A games have become comparable to those of blockbuster films. Sony’s marketing strategy for No Man’s Sky suggests that it expects the game to make hundreds of millions of dollars; this year, Sony will promote it alongside half a dozen mega-titles, including the latest installment of the Batman franchise. Adam Boyes, a vice-president at Sony PlayStation, described it to me as “potentially one of the biggest games in the history of our industry.”

All Murray has to do now is deliver. Last year, when an interviewer asked him when the universe would be ready, he said, “We are this super-small team, and we are making this ridiculously ambitious game, and all we are going to do in telling people when it is going to come out, probably, is disappoint them.” Sony’s participation meant that timing for the game’s launch had to be firmly decided, but No Man’s Sky is not an easy project to rush. Because of its algorithmic structure, nearly everything in it is interconnected: changes to the handling of a ship can affect the way insects fly. The universe must be developed holistically; sometimes it must be deconstructed entirely, then reassembled. Before I arrived, Murray warned me, “The game is on the operating table, so you will see it in parts. Other games will have the benefit of having a level that plays really well, while the studio works on other levels. We don’t have that.” The previous “builds” of No Man’s Sky that he had publicly shown—the ones that had generated so much excitement—contained choreographed elements. Features that might have been light-years apart were pressed closer together; animals were invisibly corralled so that they could be reliably encountered. Shifts in the weather that would normally follow the rhythm of atmospheric change were cued to insure that they happened during a demo. Imagine trying to convey life on Earth in minutes: shortcuts would have to be taken.

We were in a lounge on the second floor of the renovated studio; concept art hung beside a whiteboard covered with Post-its. The furniture was bright, simple, IKEA. Sitting in front of a flat-screen TV the size of a Hummer windshield, Murray loaded up a demo of the game that he had created for E3: a solar system of six planets. Hoping to preserve a sense of discovery in the game, he has been elusive about how it will play, but he has shared some details. Every player will begin on a randomly chosen planet at the outer perimeter of a galaxy. The goal is to head toward the center, to uncover a fundamental mystery, but how players do that, or even whether they choose to do so, is open to them. People can mine, trade, fight, or merely explore. As planets are discovered, information about them (including the names of their discoverers) is loaded onto a galactic map that is updated through the Internet. But, because of the game’s near-limitless proportions, players will rarely encounter one another by chance. As they move toward the center, the game will get harder, and the worlds—the terrain, the fauna and flora—will become more alien, more surreal.

Sitting in the lounge, we began on a Pez-colored planet called Oria V. Murray is known for nervously hovering during demos. “I’ll walk around a little, then I’ll let you have the controller for a bit,” he said. I watched as he traversed a field of orange grass, passing cyan ferns and indigo shrubs, down to a lagoon inhabited by dinosaurs and antelope. After three planets and five minutes, he handed me the controller, leaving me in a brilliantly colored dreamscape, with crystal formations, viridescent and sapphire, scattered in clusters on arid earth. Single-leaf flora the height of redwoods swayed like seaweed. I wandered over hills and came to a sea the color of lava and waded in. The sea was devoid of life. With the press of a button, I activated a jet pack and popped into the air. Fog hung across the sea, and Murray pointed to the hazy outline of distant cliffs. “There are some sort of caves over there,” he said, and I headed for them. The No Man’s Sky cosmos was shaped by an ideal form of wildness—mathematical noise—and the caves were as uncharted as any material caves. I climbed into one of them. “Let’s see how big it is,” Murray said.

The cave’s interior was rendered in blues, greens, purples, and browns, and the light filled it with warmth. Luminescent bits of matter, like inanimate fireflies, filled the air. Triple-A games are often self-serious, dominated by hues so dark they nearly seem black, but Murray favors vivid, polychromatic graphics. “I think that one of the reasons No Man’s Sky resonates is that, at a very reductive level, it’s bright—it’s colorful, vibrant,” he told me.

The game is an homage to the science fiction that Murray loved when he was growing up—Asimov, Clarke, Heinlein—and to the illustrations that often accompanied the stories. In the nineteen-seventies and eighties, sci-fi book covers often bore little relation to the stories within; sometimes they were commissioned independently, and in bulk, and for an imaginative teen-ager it was a special pleasure to imbue the imagery with its own history and drama. Space was presented as a romantic frontier, sublime in its vastness, where ships and futuristic architecture scaled to monumental proportions could appear simultaneously awesome and diminutive. Danger was a by-product of exploration: rockets that crashed on barren asteroids; plots by haywire computers; ominous riddles left behind by lost civilizations. “But inherently what is going on is optimistic,” Murray said. “You would read it and go, Wow, I would love to be this person—this is so exciting. Whereas at the moment a lot of sci-fi is dystopian, and you go, I would hate to be this person. How would I deal with it?”

No Man’s Sky’s references may be dime-store fiction, but the game reimagines the work with a sense of nostalgia and a knowing style that is often more sophisticated than the original. “One thing a lot of video games are missing is a very confident sense of style,” Frank Lantz, the director of New York University’s Game Center, told me. “No Man’s Sky has a personality.”

I approached a cave that looked out on the sea, and Murray gestured toward a portion of the digital geology. “I haven’t seen that before,” he said, and took the controller to get a better look. Murray’s primary coding contribution is to planetary terrain, and he had developed a special appreciation for such formations. After exploring for a bit, he said, “Sorry. You can have the controller back.”

From inside the cave, I turned and approached an opening that looked out upon a ridge high above the shore. “What happens if I jump off?” I asked.

“You’ll be fine,” he said. “We didn’t want you to break your legs and get hurt. It is about exploring. We didn’t want people feeling nervous.”

Each planet had a distinct biome. On one, we encountered a friendly-looking piscine-cetacean hybrid with a bulbous head. (Even aggressive creatures in the game do not look grotesque.) In another, granular soil the color of baked salt was embedded with red coral; a planet hung in the sky, and a hovering robot traversed the horizon. “Those are drones,” Murray said. “They will attack you if they find you killing animals or illegally mining resources.” On a grassy planet, doe-eyed antelope with zebra legs grazed around us. Mist rose off the grass as I headed down a ravine shaded by trees. “This is a place where no one has been before,” Murray said. The biome was Earth-like in light and in color, naturalistic. As I descended, the ravine deepened until rock facades took shape on either side. In spite of the work’s semi-finished state, the world was absorbing. “I’m sorry there’s no game-play element on this planet yet,” Murray said. His mind turned from the screen in front of us—the six planets, tidily assembled for the demo—to the full version of No Man’s Sky on the operating table on the studio’s first floor, below us. Until many improvements were fully realized, the whole of it would inevitably look worse than what we were seeing. “You can lose sight that it once looked like this,” he said.

This version of the game—a frequent reference point for the studio—was a reminder of a public promise: the presentation that Murray had given at E3, where he stood on a huge stage with images of No Man’s Sky projected onto ninety-foot screens. “There were five thousand people in the audience, and at least five million watching at home,” he told me. “I sat backstage, and, before walking out, I had a feeling that I could go to sleep—just turn around and go.” One of the studio’s programmers who was with Murray backstage recalled, “Sean got whiter and whiter—he was just catatonic.” To overcome his nerves, Murray focussed his mind on the story of the game, beginning with the studio’s origins. He told me, “By the time I walked out, I could have burst into tears, because what I was going to say was that this is basically the game I’ve always wanted to make.”

Murray’s earliest memories are of life on a cane farm in Brisbane, Australia. He was born in Ireland, but his parents migrated to Australia when he was two years old. “We basically lived in a glorified shed,” he told me. “It was up on stilts, and it had a corrugated-iron roof.” Two years later, Murray’s parents moved again, to work on a remote million-acre ranch in Queensland. The settlement resembled an alien outpost, with its own power-generation system and its water pumped on-site. Visitors who wanted to avoid a four-hundred-mile drive on a rutted track had to fly in. (The ranch had seven airstrips and an abandoned gold mine.) Dust storms swept across the desiccated soil. Merely crossing the property was like an expedition. “You would go out to check that the windmill, or whatever, was working,” he said. “And you always had to go out in twos. As a kid, you were told that, if something happened to the person you were with, then find some shade, and if there is no shade don’t go looking for it. You will survive for three days without water and without food, and so you have only one job: gather kindling to light a fire. You stay exactly in the same place, and you light a fire at set times, and that’s it. There is a plan: we can fly over, and in three days we can cover the whole grid.” Murray often accompanied his father on multi-day treks. At night, they camped under pristine night sky, with all of space arcing above them.

In the outback, Murray became fascinated with sci-fi. When he first encountered “Dune,” he said, “I can remember being hungry reading it, forgetting to eat.” Years later, when he formed Hello Games, he told his co-founders—two coders named Ryan Doyle and David Ream and an artist named Grant Duncan—to consider their childhoods as source material for games. “I said, ‘Think back to when you were a kid. What did you want to be? A cowboy, an astronaut, a stuntman, a fireman, a policeman, whatever.’ ” Working in Murray’s living room, the four men at first devoted their attention to fundamentals, writing software to determine how objects would behave in a theoretical game space. “We mentioned Pixar a lot, because their work is colorful but not childish,” Duncan told me. The inspiration for Joe Danger came from a stuntman figure that Duncan found in a box of old toys.

The partners worked for a year, and went nearly broke. “I had sold off my PS3,” Murray told me, referring to his PlayStation. “We were down to the bare essentials.” For the release, in June, 2010, Murray bought some cheap cider. “We decided, we are going to drink cider, and it will come out and do what it will do,” Murray said. The game did not appear online in the United Kingdom until after midnight. When it first loaded, the screen was black, causing momentary panic. But within an hour the partners had made back their money.

Murray started No Man’s Sky one morning two years later, during a difficult negotiation with Microsoft over the marketing for Joe Danger’s sequel. “Everyone else was at home,” he recalled. “I was in the studio on my own, and I just started programming. I was furious, and I kept working until three in the morning. Looking back, I think I had the equivalent of a midlife career crisis. What is the point of these games? Like, Joe Danger—how impactful is it?” Murray and his co-founders had joked that they would one day make an ambitious game, which they called Project Skyscraper. The following day, he told Duncan and Ream, “We’re doing it.” He had created only a small patch of sample terrain, without a clear sense of what it would be, and Ream told me, “The thing was quite abstract, and we were like, What are you doing?” Duncan was skeptical. Artists he knew were dismissive of the technique that Murray was using; one had warned him that the results “look like shit.”

Duncan and Ream began to design a relatively conventional game, in the mold of Joe Danger—another humorous take on a childhood dream profession. Their working title was Space Cadets. But Murray urged them to consider the project in more open-ended terms. “I had this feeling: I want to start a new company, like almost an alternate path for Hello Games,” he told me. He split his company into two, and for months the three men, along with a coder named Hazel McKendrick, worked on No Man’s Sky in secrecy, in a locked room.

To build a triple-A game, hundreds of artists and programmers collaborate in tight coordination: nearly every pixel in Grand Theft Auto’s game space has been attentively worked out by hand. Murray realized early that the only way a small team could build a title of comparable impact was by using procedural generation, in which digital environments are created by equations that process strings of random numbers. The approach had been used in 1984, for a space game called Elite, which Murray played as a child. Mark Riedl, the director of Georgia Tech’s Entertainment Intelligence Lab, told me, “Back in those days, games had a lot of procedural generation, because memory on computers was very small; it was largely forgotten, but now it is being rediscovered.” (Minecraft, an expansive world that was designed by only one person, also uses the technique.) Games based on procedural generation often suffer from unrelenting sameness, marked by easily detectable algorithmic patterns (imagine a row of more or less identical trees, stretching to infinity), or from visual turmoil. But Murray hoped that if a middle ground could be achieved he could create graphically rich environments worthy of discovery—a fictional version of exploration that had a grain of reality to it.

Once Murray decided on the basic mathematical architecture of the game, he needed random numbers to feed into it. No computer can generate true randomness, but programmers use a variety of algorithms, and sometimes the physical limitations of the machine, to create approximations. “Computers can understand numbers only of a set size,” Murray told me. “When you are building a computer, you are literally saying, This is where a number gets stored, and this is how many digits can fit in that space.” For a game console, that space is sixty-four bits. When a player first turns on No Man’s Sky, a “seed” number—currently, the phone number of a programmer at Hello Games—is plugged into an equation, to generate long strings of numbers, and when the computer tries to store them in that sixty-four-bit space they become arbitrarily truncated. “What you are left with is a random number,” Murray said. The seed defines the over-all structure of the galaxy, and the random numbers spawned from it serve as digital markers for stars. The process is then repeated: each star’s number becomes a seed that defines its orbiting planets, and the planetary numbers are used as seeds to define the qualities of planetary terrain, atmosphere, and ecology. In this way, the system combines entropy and structure: if two players begin with the same seed and the same formulas, they will experience identical environments.

The design allows for extraordinary economy in computer processing: the terrain for eighteen quintillion unique planets flows out of only fourteen hundred lines of code. Because all the necessary visual information in the game is described by formulas, nothing needs to be rendered graphically until a player encounters it. Murray compared the process to a sine curve: one simple equation can define a limitless contour of hills and valleys—with every point on that contour generated independently of every other. “This is a lovely thing,” he said. “It means I don’t need to calculate anything before or after that point.” In the same way, the game continuously identifies a player’s location, and then renders only what is visible. Turn away from a mountain, an antelope, a star system, and it will vanish just as quickly as it appeared. “You can get philosophical about it,” Murray once said. “Does that planet exist before you visit it? Sort of not—until the maths create it.”

Initially, the system proved fantastically difficult to control. It was generating planetary terrain that was wild, alien-seeming, and also impossible to traverse. If Murray pushed the system in the other direction, the terrain became dull and repetitive. There were also specific natural features, such as rivers, that did not lend themselves easily to equations. To make a river in a conventional game, an artist creates a mountain, places a digital drop of water on it, and maps the water’s trajectory downward. “That is the correct way,” Murray told me. But the process involves laborious computation, and requires that the topography be known in advance. Because of No Man’s Sky’s algorithmic structure—with every pixel rendered on the fly—the topography would not be known until the moment of encounter. Theoretically, the game could quickly render a sample of the terrain before deciding that a particular pixel belonged to a river, but then it would also have to render a sample of the terrain surrounding that sample, and so on. “What would end up happening is what we call an intractable problem to which there is only a brute-force solution,” Murray said. “There’s no way to know without calculating everything.” After much trial and error, he devised a mathematical sleight of hand to resolve the problem. Otherwise, the computer would have become mired in building an entire world merely to determine the existence of a drop of water.

Every morning, at a little past ten, Murray leads a brief meeting with his team. A dozen coders and artists stand among the rows of computers, or swivel their chairs around. In a quick rundown, problems are identified, goals set; in the evening, work is checked into a master build. Murray delegates readily but watchfully.

During my visit, four artists outlined their plans, and then sat down to work. The artists devise archetypes for the coders’ algorithms to mutate. One spent a day making insects: looking up images on Pinterest, designing features for an insect archetype, studying how the algorithms deformed the archetype in hundreds of permutations, then making corrections. “It’s a constant slog of iterating and polishing,” the art director, Grant Duncan, told me. He was working that day on architectural modules that could be combined in myriad ways. Because small changes can have unpredictable effects—the color of a single plant infecting every tree, rock, and animal on a planet—his team uses an algorithmic “drone” that navigates the universe, taking snapshots to measure the repercussions of decisions. Occasionally, Duncan stopped his work to offer suggestions. Reviewing some insects, he said, “Except for the colors, these shapes are kind of working—but the others are bonkers.”

Murray sat down with David Ream, whose focus is coding the game-play systems. Ream had been working to make spaceships handle more realistically in flight, and he wanted Murray to test his work. “I have to give the controller to Sean, because I find that I naturally play the game so that it works, because I know all the numbers,” Ream said. “And also because we have our strong bonds, so I can tell Sean to fuck off.”

Murray played for a few minutes, dogfighting with enemy ships. “This is so much more enjoyable than it was on Sunday,” he said. But he was worried that excessive realism would confuse players who were unaccustomed to the frictionless quality of motion in space. He suggested some tweaks. During the testing, Murray noticed that his ship had exited a planet’s atmosphere too rapidly, without the drama it had in the E3 build. “We’re missing something that used to be there,” he said. “It was a surprise to be suddenly in space.”

Hazel McKendrick walked over and said, “The atmosphere isn’t as thick.” She had adjusted formulas to provide a more natural effect of sunlight passing through it, and a better view of nearby planets. To re-create the old feel, she suggested, the atmosphere’s depth could be artificially increased as the ship passes through.

“So, annoyingly, by doing it wrong you get a nicer effect,” Ream said.

Throughout the day, other members of the team worked on shadows, on creature artificial intelligence, on imbuing objects with “collision,” or physicality. After a coder gave trees and rocks collision, they became destroyable; he shot at a hillside, causing rocks to tumble down, hitting one another in a cascade. Peculiar problems had emerged from the sphericality of planets; in conventional video games, digital spaces are perfectly flat. Until gravity was precisely calibrated, objects sometimes fell off planets. One of the programmers, Charlie Tangora, described a problem with cowlike creatures that kept walking on cave ceilings; it took some troubleshooting before he realized, “Oh, wow. You’re in the Southern Hemisphere. Everything is upside down.”

When Murray wasn’t being pulled away from his computer, he worked on the terrain. He told me that he was always searching for ideas. Last year, he saw the film “Interstellar,” which features scenes of a lifeless snowy planet that “had some very perfect ‘mathlike’ terrain.” The next day, he developed formulas that would create similar crevasses. More recently, he had noticed geological formations that an artist had hand-designed for another video game, and realized that the algorithms of No Man’s Sky were not equipped to make them. The problem nagged at him, until he found an equation, published in 2003 by a Belgian plant geneticist named Johan Gielis. The simple equation can describe a large number of natural forms—the contours of diatoms, starfish, spiderwebs, shells, snowflakes, crystals. Even Gielis was amazed at the range when he plugged it into modelling software. “All these beautiful shapes came rolling out,” he told Nature. “It seemed too good to be true—I spent two years thinking, What did I do wrong? and How come no one else has discovered it?” Gielis called his equation the Superformula.

Murray, sitting before his monitor, typed the Superformula into the terrain of a test planet. He began simply, creating walnut-shaped forms that floated in an infinite grid over a desert. The image resembled a nineteen-eighties album cover, but the over-all look was not the point. Whenever he refreshed the rendering, the floating shapes changed. Many were asymmetrical, marred by depressions and rivulets. Game designers refer to lines of code that require lots of processing time as “costly.” The Superformula is cheap.

“One of the hardest things for us to do is to create coherent shapes,” he told me as he worked. In order to produce varied landscapes, a formula must be able to cope with a wide range of random information without generating mathematical anomalies that cause glitches. “This sounds ridiculous, but it is hard to find a formula that you can rely on,” he said. The Superformula appeared to be reliable. He pointed to a rocky overhang, which looked like desert geology sculpted by harsh erosion. “This is quite naturalistic,” he said. He added more noise to the formula, rotated the shapes it made, played with their scale, buried them beneath the planet surface. “This is effectively more turbulence entering the maths.” He envisioned using the Superformula throughout the game, especially at the center of the galaxy, where landscapes would become more surreal. With only small shifts in its parameters, the equation was producing impressive variability. In one rendering, it produced rolling hills. Murray refreshed the screen: a star-shaped rock formation appeared. He seemed pleased. “It’s always a good sign when I am clicking the button, and there is that slight amount of excitement,” he said.

The allure of taking one more peek at the unknown had a way of distracting even the game’s creators. At one point, I sat next to Duncan, who was populating a test planet with alien fungus. “I’m trying to develop some weirder vegetation,” he told me. Birds flew high above a towering black obelisk—space architecture inspired by John Harris, a British illustrator. Duncan had activated the bird algorithm, but, oddly, a herbivorous dinosaur had also appeared. “I made this world for this test, and I have never encountered animals on it before,” he said. “I don’t know what it’s going to do.” The dinosaur scampered off. After several minutes, I asked what attributes of the fungus he was studying. “I’m just exploring,” he said, sheepishly. “Sometimes I’m, like, What am I doing? I’m supposed to be working.”

By May, the team was working furiously. Murray’s hair and beard were growing wilder. Discussions with Sony became more complicated; the company was banking on No Man’s Sky as a genre-defying hit, and, as its marketers began to consider different ways to promote it, the story of the game was slipping from his full control. Murray told me that he couldn’t sleep at night. “The biggest worry for me is that we release the game because of all the momentum behind it before we are happy with it,” he said. Because of the game’s scope, and because he had decided not to reveal key features, he feared that it had become a Rorschach test of popular expectation, with each potential player looking for something in it that might not be there. “Hype is a difficult taskmaster,” David Braben, one of the creators of Elite, told me when I asked him what he thought about the game.

Even a feature as simple as the Superformula—a hundred and twenty lines of code—created complications when it was written into the terrain-generation system. When I asked Murray how it was working, he told me, “It’s cool, though it currently plays hell with creature A.I.” He was spending as much time as he could coding, but distractions were hard to block.

People at Sony wanted to issue a companion book, and, once he realized that it might be inevitable, he decided to get involved. One afternoon, he met with Dave Gibbons, the co-creator of the “Watchmen” comic series, to discuss his possible role as editor. In the upstairs lounge, they talked excitedly about Philip K. Dick, and about “Terran Trade Authority,” an old sci-fi series that Murray had loved. Then Murray turned toward the flat-screen TV and brought Gibbons onto a snowy mountainous planet, from a build that had been created after E3. “A living, breathing universe,” he said. “I can walk in any direction for days and days, and I will eventually walk the entire planet and come back to where I started.”

“So you could really explore one planet and map it,” Gibbons said.

“For some people, that will be all they do, and they’ll be able to have quite a nice game,” Murray said. He climbed into a ship, and flew through an asteroid belt. “The thing that we haven’t really shown publicly, but I think is really cool, is that if I press a button I can pop out to a galactic map,” he said. He pressed a button, and all of space shrank into a pinpoint of light, representing that solar system.

The galactic map—as bright and compelling as an image from a Carl Sagan documentary—gave the ship’s location by framing its proximate sun in a white square. A panel of text noted the solar system’s computer-generated name, Ethaedair; a diagram of vectors indicated stars that were reachable with the ship’s hyperdrive. “This has been in games before, but it has always been a fake,” Murray said, gesturing to the map. “Normally, it would be a painting that somebody has made, and there would be two little levels that you can go between, or ten levels, each set on a pretend ‘solar system.’ ” Like a magician working toward a showstopper, he added, offhandedly, “But it is quite nice to just pull around . . .” He manipulated his controller, and all of space rotated around Ethaedair’s sun. Stars and plumes of luminous cosmic matter arced past; what had seemed like a two-dimensional representation suddenly revealed itself to be full of depth. Gibbons gasped, and Murray began to speak more softly: “If I pull back a bit, you start to get a sense of the size of what we are building.” Millions of stars drifted by. Gibbons laughed softly. “It’s like a huge box of chocolates!” he said.

“Maybe I should just go a little faster,” Murray said. Light-years of space unfolded at a terrific rate. It may not have been the universe as it actually was, but there was nonetheless an awesome reality on display: the system’s vast mathematics. Murray turned toward a phosphorescent glowing orb. “That’s the center,” he said. This version of the game allowed Murray to leap to any solar system he wanted, but, drawing out the suspense, he moved deeper into the galactic map’s three-dimensional space. “This build was brought together so I could do a demo onstage. I chickened out, because when I press this button, basically, I don’t know what we’re going to see—and it can be a really weird way to end a demo. Something might go terribly wrong. Or we might find a planet that is quite boring. But I can see now that I should have gone with it, because even when it is boring it still is something new.”

“It is a bit like it really does exist, isn’t it?” Gibbons said.

Murray stopped at a star cluster and admired its density. Finally, overcoming his hesitancy, he picked a destination. “I can’t promise if this is going to be interesting,” he said. The map vanished. He was back in his cockpit. His hyperdrive kicked on. Then all of space blurred, and the ship hurtled into the unknown. (source:newyorker)

下一篇:长尾开发者或将推动行业格局巨变

闽公网安备35020302001549号

闽公网安备35020302001549号