从系统性层面来解构游戏的设计制作

作者:Lennart Nacke

比起在此衡量游戏的真正定义,我们想要着眼于什么才是对游戏设计师最有帮助的。

“设计是设计师创造参与者将遭遇的情境的过程,意义也是由此而生。”—-Katie Salen和Eric Zimmerman

这一来自《Rules of Play》的引用将作为游戏设计师的我们需要关注的内容概述为几大点:(1)上下文,可能是你在游戏中遇到的空间,目标,故事和行为。(2)参与者是按照你的游戏上下文行动的玩家们,即通过操控角色或探索,他们将进入你的游戏世界进行体验。(3)意义是我们在之前谈论有意义的选择时已经提到过的。当玩家在你的游戏中采取行动,玩家将会感受到代理,这便是有意义的游戏。这里的意义与个体玩家在游戏中的某些遭遇的重要价值是相互维系的。甚至在现实生活中,意义对于我们来说也非常重要,因为它能够帮助我们在现实世界中前进,并理解我们身边的人与世界。我们每天所进行的互动都是由意义所引导。

为了开发一款游戏,我们最好能在设计过程的一开始将自己限制在游戏的某些核心元素中。就像我们是从我们在所有游戏中找到的头脑风暴元素开始。然而就像在《Extra Credits》视频中提到的,并不存在任何过程能够定义游戏到底是什么。我们只是使用这个作为起点往大脑中填充我们将创造的游戏中的元素。我们必须从某一处开始创造这个新媒介,而本文中所列出的内容便会是一个不错的起点。

游戏作为系统

游戏是一种独立的正式系统,主观地代表现实的一个子集。—-Chris Crawford

我们已经将游戏定义为作为现实的一个子集存在的一个空间,并带有界限和规则(我们甚至提到了魔法阵的概念)。

游戏可以被当成一套元素,但它们却不只如此,经常还包含内部关系以及帮助它们进行互动的元素的状态。基于这一层面,我们很容易将游戏当成系统。而现在系统也可以被当成是彼此影响的道具组合。这些道具间的互动可以形成一些与个体零件不同的模式(例如整体比起个体的总和还棒)。Littlejohn和Foss所讨论的4个系统元素也出现在《Rules of Play》中(第51页):

1.目标。这指的是元素,变量或系统的一部分。这些内容可以是实体的或者抽象的。

2.属性。这是系统和系统中的目标所具有的属性和指令。

3.内部关系。系统中的目标通常与其它目标具有一种内部关系。

4.环境。系统是受到其周边环境的影响。

游戏可以被塑造成不同形式的系统,如正式的,文化的或者经验上的系统。如果你将游戏当成一种正式数学系统进行分析,那么你的分析方法将不同于作为文化或经验上的系统。这些系统经常被嵌入其它系统中。就像文化系统包含了游戏的经验和正式系统。将游戏作为正式系统与经验系统之间的主要区别是正式系统更加独立,而经验系统既独立又灵活(游戏邦注:可以基于某种形式在系统和环境间交换着)。

将游戏当成系统并揭开其共享属性的最简单的方法便是着眼于两款游戏并基于它们的共同点和不同点进行比较。

正式元素能够帮助你创造游戏结构。正是这些正式元素之间的关系构成了一款游戏。因此,作为游戏设计师的我们必须了解这些正式游戏元素。这并不是游戏元素的独家列表,如果我们能够结合这些元素,我们便能够创造不同的游戏元素,并因此创造出具有创造性的互动形式和游戏玩法。基于这些工具,你将能够在自己的游戏中创造有意义的决策。

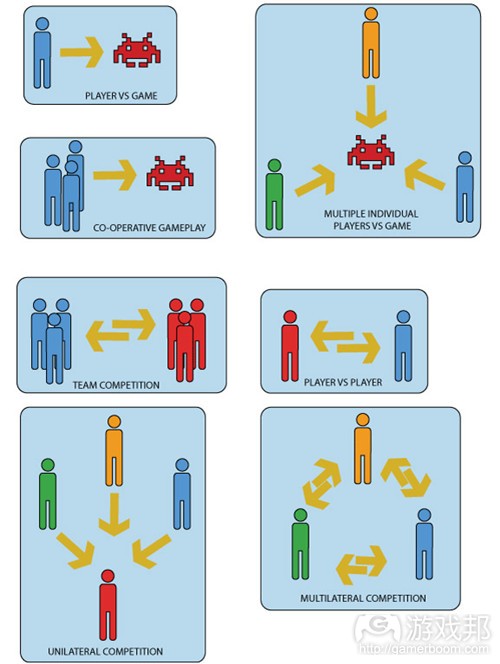

1.玩家。游戏设计需要让玩家与玩家和游戏系统进行互动。玩家是娱乐活动中自愿且活跃的参与者。他们加入游戏,在游戏中消费与投资。他们可以是活动中潜在的赢家。当玩家接受了lusory态度,他们便能够进入游戏中的魔法阵并沉浸于游戏世界中。这意味着他们经常会被邀请到游戏中,如通过一下特别的仪式或社交奖励。邀请游戏对于拥有lusory态度的玩家来说非常重要。每次游戏中的玩家数可能是个变量。基于参与游戏的玩家数量,玩家的体验也会不同。不同玩家可能会在游戏中扮演不同的角色。玩家可以参与团队并为其他团队成员分配行动。在角色扮演游戏中,玩家的角色可能促进或抑制其他玩家的行动,但通常情况下玩家总是具有不同的游戏风格,这让玩家在扮演同一个角色的时候能够面对不同比赛。

2.就像我们曾经提过的,目标有助于激励玩家沉浸于游戏玩法中。最佳游戏目标看似可实现,但其实还是具有一定的挑战性。作为游戏中的玩家,你想要努力去实现目标。即在游戏最后你将获得最多经验值,或者直至关卡最后你仍然活着。玩家完成目标的需求将成为衡量他们是否沉浸于游戏中的标准。让我们举例来说:

1)捕获。玩家必须避免在消灭敌人属性(通常是指区域或单位)时被捕获或杀死。

2)追逐。玩家需要躲避或捕捉敌人。

3)竞赛。玩家必须赶超别人先完成目标。

4)排列。玩家必须基于空间或概念结构去排列他们的组件。

5)拯救或逃跑。玩家必须获得一些明确的单位或道具去确保安全(无需妥协)。

6)禁止行为。玩家必须想办法让敌人打破规则或放弃策略。

7)构造。玩家必须构造,维持或管理游戏目标。

8)探索。玩家必须探索未知游戏领域。

9)解决方法。玩家必须解决一个问题或谜题(有时候是在敌人解决之前)。

10)以智取胜。玩家必须获得并使用知识,以智胜过敌人。

3.程序。这些都是游戏规则所允许的行动或方法。它们可以是游戏过程中玩家所采取的行动的特定指令。它们也可以指代特定的控制组合。在计算机游戏中,它们将处理玩家的输入。程序可以指定在游戏魔法阵以外不可行或无效的行动。通常情况下你必须回答谁在哪里什么时候如何做了什么的问题。程序所明确的玩家行动可以进行如下划分:

开始(如何进行游戏,同时也引出了玩家的管理)

进程(这是在游戏玩法中持续发展的程序)

特技(这是基于其它元素以及游戏状态的改变才有的行动)

解决(这些行动将带你走向游戏最后)

4.规则。这是你的游戏的真正目标和概念;它们是指创造游戏系统的组块。作为游戏设计师,你总是希望能在规则集中描述出所有可能情境下的行动。你的规则集将指定玩家能做以及不能做的所有内容。这意味着你经常需要限制玩家能够做的行动,并且你需要思考游戏对玩家行动所作出的反应。规则是你的游戏世界的权威。它们就像玩家在进入游戏时需要遵循的荣誉代码一样(这与想要进入魔法阵的lusory态度是相联系的)。如果玩家不能遵循规则,他们便会离开游戏。总的来说规则具有三大目的:

1)定义目标和条件

2)限制玩家行动

3)决定对玩家的影响

5.资源。这些是玩家在到达个人目标时非常重要的游戏目标。这些道具的价值是由其匮乏性和实用性所决定。这些道具对于玩家的价值经常是由它们帮助玩家实现目标的能力所决定。作为设计师,你可以控制道具的实用性,你可以引导玩家去寻找资源,你也能够设置系统去管理资源分配以及它们在何时开始匮乏。游戏中常见的资源是:

生命

单位

健康

货币

行动

库存

时间

6.矛盾。在游戏的程序和规则中会出现矛盾去阻止玩家实现目标。目标经常会引导玩家到达这些矛盾情境。在许多第一人称射击游戏中,当玩家或非玩家角色尝试着杀死你时主要矛盾也始终活跃着。就像“弹球戏”中的矛盾便是使用机械装置阻止球离开游戏区域。

当目标引导着玩家前往不利于其目标的规则和程序时,矛盾便会出现。

游戏中常见的三种类型的矛盾:

1)障碍。可能是以实体或心理形式出现。实体障碍可能是你的弹球戏的flippers的长度或者弹开的球的缓冲器。心理障碍可能是缺少一个道具去完成冒险游戏中的一个谜题或者在数独游戏中计算正确数字的挑战。

2)对手。游戏中的其他玩家或计算机所操控的敌人。

3)困境。这是玩家所面对的问题选择。这是一种策略性决定,即在前进前先衡量结果。

7.界限。这是现实世界的边界(将魔法阵与现实世界分隔开来)。这同样也是关于游戏中唯一可能的行动,但却与游戏外部具有不同的结果。这也是关于游戏领域,天空盒以及你的游戏世界中其它有限的几何体。

8.结果。游戏的结果不一定能够培养玩家的兴趣。在游戏中,结果通常都是可衡量(如分数)且不均衡的(如一支团队/一个人将获胜)。基于玩家的不同目标,获胜条件也会不同。因为玩家已经投入了许多时间和情感与游戏中,所以我们很难创造一种能够匹配玩家这种投资的结果。

“每一款游戏都有其规则—-游戏也是由此而定义。”—-David Parlett

(本文为游戏邦/gamerboom.com编译,拒绝任何不保留版权的转功,如需转载请联系:游戏邦)

The formal systems of games

- Lennart Nacke

Rather than pondering on the exact definitions of game here (many of which can be found in Rules of Play, Chapter 7), we want to look at what’s most useful to us as game designers.

“Design is the process by which a designer creates a context to be encountered by a participant, from which meaning emerges.” (Katie Salen and Eric Zimmerman)

This quote from the Rules of Play book encapsulates the main items that we should focus on as game designers: (1) Context, which can be the spaces, objects, story and behaviours that you encounter in games. (2) Participants are your players that act upon your game context for example via manipulation or exploration. They inhabit your game world to play. (3) Meaning is a concept that we have already mentioned in the last week when we talked about meaningful choice. When players take actions in your game, meaningful play should emerge from the agency that players feel. Meaning here is tied to the value of significance of something encountered in a game for the individual player. Even in real life, meaning is important to us because it helps us navigate through our world and interpret the people and the world around us. Our everyday interactions are guided by essentially guided by meaning-making.

To develop a game, it is best to constrain ourselves at the start of our design process to some core elements of games. We begin by brainstorming elements that we find in all games. The results of such a brainstorm from class is shown below. However, as mentioned in the above Extra Credits video, there is no progress in exhaustively defining what exactly a game is. We simply use this as a starting point to wrap our head around the elements in games that we are going to work with as game designers. We have to start somewhere to develop this new medium and this list serves as a good starting point.

Games as Systems

A game is a closed formal system that subjectively represents a subset of reality. (Chris Crawford)

We have already identified games as a space that exists as a subset of reality with boundaries and rules (we have even mentioned the concept of the magic circle in class, see below for an extra credits video on the concept).

We have already identified games as a space that exists as a subset of reality with boundaries and rules before. Games can be seen as sets of elements, but they are much more than just a set, often having internal relationships and states of elements that help them interact. At this level, it is most sensible to refer to games as systems. Now, systems can be seen as sets of items that can affect one another. The interaction among these set items can form patterns that are distinct from its individual parts (i.e., the whole is greater than the sum of its parts). Littlejohn and Foss discuss four system elements that are mentioned in Rules of Play (p.51) as well:

1.Objects. This refers to elements, variables or parts of a system. These could be physical and/or abstract nature.

2.Attributes. These are the properties or qualities that a system and the objects within the system can have.

3.Internal relationships. The objects in a system are usually in an internal relationship to one another.

4.Environment. Systems are influenced by their context that surrounds them.

Games can be framed as different forms of systems as well, such as formal, cultural or experiential systems. If you analyse a game as a formal mathematical system, you analyse a it differently than if you analyse it as a cultural or experiential system. These systems are often embedded in one another. A cultural system encompasses the experiential and formal system of a game. The main difference between framing games as a formal or as an experiential system is that formal systems are closed (they can be analysed independent from their environment) and experiential systems can be closed but also open (i.e., they have some form of exchange between the system and the environment).

The easiest way to start seeing games as systems and to uncover their shared properties is to look at two games and compare them in terms of their commonalities and differences.

Formal elements help create a games’ structure. The relationship between these formal elements is what forms a game. Therefore, as game designers we have to get acquainted with these formal game elements. This is not an exclusive list of game elements and by combining them, it is possible to create different game elements, to create novel forms of interaction and gameplay. With these tools, you will hopefully be able to create meaningful decisions in your own games.

1.Players. Game design calls for players to interact with one another and the game system. Players are voluntary, active participants in the entertainment activity. They partake in it, they consume it and they are invested in it. They can be potential winners of the activity. When players adopt the lusory attitude, they can enter the Magic Circle of games and immerse themselves in the game world. This means that there is usually an invitation to play, such as recognizable rituals or social offerings for playing. The invitation to play is important for players to have a lusory attitude.The number of players can be variable or fixed for a game. Players will have different experiences based on the amount of other players partaking in a game. Different players can adopt different roles during play. Players can play in teams and define actions for team members. Within role playing games, a player role can facilitate or inhibit a player action, but often players have different play styles, which allows for different matches even when players play the same role.

2.Objectives. As we have already mentioned in the last lecture, objectives are important for the motivation of your players to engage in gameplay. The best game goals seem attainable but are still perceived as challenging. You want to be able to work as hard as necessary to achieve your own objectives as a player in a game. Examples are getting the most XP at the end of a game or staying alive until the end of the level. The player’s need to complete objectives serves as a measure of player involvement in games. Here are some examples:

1.Capture. Players have to avoid getting captured or killed while destroying some opponent properties (commonly some form of terrain or units).

2.Chase. Players have to elude or catch an opponent.

3.Race. Players have to reach a goal before anyone else does.

4.Alignment. Players have to align their pieces in a spatial or conceptual configuration.

5.Rescue or Escape. Players have to get some defined units or items to safety without being compromised.

6.Forbidden Act. Players have to get the opponents to break the rules or to abandon a strategy.

7.Construction. Players have to construct, maintain, or manage game objects.

8.Exploration. Players have to explore unknown game areas.

9.Solution. Players have to solve a problem or puzzle (sometimes before the opponents solve it).

10/Outwit. Players have to gain and use knowledge to outwit their opponents.

3.Procedures. These are actions or methods of play allowed by a game’s rules. They can be specific instructions of what actions to take during play. They can also refer to a specific set of controls. In a computer game, they would serve to process the input of a player. Procedures can specify actions that are impossible or inefficient outside of the magic circle of the game. Essentially, you have to answer who does what where and when and how? Player actions as specified by procedures can be split up into the following:

Starting (How the game in put into play, also leading into onboarding of players)

Progression (These are the ongoing procedures running during gameplay)

Special (These are actions that are only available based on other elements and changes to the game state)

Resolving (These actions bring your game to an end)

4.Rules. These are the exact objects and concepts of your game; they are the building blocks of the game system. As a game designer you want to be able to describe the actions for all possible situations in your rule set. Your rule set specifies everything a player can and cannot do. This means that you often have to limit the actions a player is allowed to do and you have to think about reactions of the game to player actions. Rules are the authority of your game world. They are like a code of honour that players adhere to when entering play (this is tied to the lusory attitude of being willing to enter the magic circle). If players don’t follow the rules, they are leaving the game. In summary rules serve three main purposes:

1)Defining objects and conditions

2)Restricting player actions

3)Determining effects on players

5.Resources. These are game objects that have a value for players in reaching their individual objectives. The value of these items can be determined by their scarcity and utility. The value for players (i.e., utility) is often scaled by how much an item helps a player achieve a goal. As a designer you control the availability (i.e., scarcity) of an item, you can help guide the player to find resources and you can put systems in place that govern how resources are managed and when they become scarce. Common resource examples in games are

Lives

Units

Health

Currency

Actions

Inventory

Time

6.Conflict. Conflict emerges through procedures and rules in the game that prevent a player from achieving their goal. Objectives often guide players to these conflict situations. The main conflict in many first-person shooters is to stay alive while player or non-player characters try to kill you. The conflict in Pinball would be to keep the ball from rolling out of the playing field only with the mechanical devices (often flippers) the machines provides to you.

Conflict emerges when objectives guide players toward rules and procedures that work against the player goal.

Three types of conflict are common in games:

1)Obstacles. These can be in physical or mental form. Physical obstacles could be the length of your Pinball flippers or the bumpers that the ball bounces off of. Mental obstacles can be a missing item to complete a riddle in an adventure game or the challenge of calculating the right numbers in Sudoku.

2)Opponents. Other players in a game or computer-controlled enemies.

3)Dilemmas. These are problematic choices that a player is

faced with. It’s a strategic decision, where the consequences have to be weighted before proceeding.

7.Boundaries. The is the border to the real world (the separation of the magic circle and real world). This also relates to actions that are only possible in a game but would have much different consequences outside the game boundaries. It can also relate to the playing field, the skybox, or other limiting geometry in your game world.

8.Outcome. The outcome of a game has to be uncertain to foster player interest. In games the outcome is often measurable (e.g., points) and uneven (i.e., one team/person has to win). Winning conditions are different from player objectives. Since players have invested much time and emotion into a game, it is hard to create a resolution that satisfies this investment of players.

“Every game is its rules – for they are what define it.” (David Parlett) (source:gamecareerguide)

上一篇:万字长文,Pascal Luban关于游戏后期测试行为的分析

下一篇:如何在没有办公室的情况下有效工作

闽公网安备35020302001549号

闽公网安备35020302001549号