万字长文,Ian Schreiber从多角度谈游戏制作系列2

相关内容参阅:万字长文,Ian Schreiber从多角度谈游戏制作系列1

推荐阅读内容

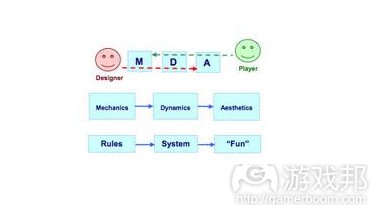

* LeBlanc、Hunicke和Zabek的《MDA Framework》,这是在游戏领域受到广泛关注的少数学术论文(游戏邦注:这也许要归功于3位作者都是资深游戏设计师)。文章有2块内容尤 其突出。首先是Mechanics/Dynamics/Aesthetics(MDA)构想,这令我们能够探究规则同用户体验,用户同设计师之间的关系。第二块是“8种趣味”。

现在就来谈谈《MDA Framework》……

LeBlanc等基于Mechanics、Dynamics和Aesthetics定义游戏:

* Mechanics是游戏“规则”的同义词。这些是游戏运作的限制条件。游戏如何形成?玩家能够采取什么行动,这些行动会给游戏状态带来什么影响?游戏何时结束,如何确定解决 方案?这些都由Mechanics定义。

* Dynamics呈现规则运作时的游戏。规则衍生什么策略?玩家如何进行互动?

* 这里的Aesthetics不是指游戏的视觉元素,而是游戏的用户体验:Dynamics带给玩家的影响。游戏是否“有趣”?体验是令人沮丧,枯燥,还是饶有趣味?体验是否具有情感、 智力魅力?

在《MDA Framework》问世前,“Mechanics”和“Dynamics”就受到设计师的广泛运用,而“Aesthetics”也开始受到更多关注。

设计过程

谈完定义,接着就是此理论的重要性?这是《MDA》文章的要点之一。游戏设计师只直接创建Mechanics。Dynamics源自Mechanics,而Aesthetics源自Dynamics。游戏设计师或许希 望自己能够设计游戏体验,或者至少这是游戏设计师心中的终极目标,但作为设计师,我们需要创建游戏规则,希望理想体验能够从我们的规则中诞生。

这就是为什么游戏设计有时被当作二级设计问题:因为我们没有定义解决方案,我们只是定义其他能够间接创造解决方案的内容。这就是为什么游戏设计如此困难。或者,至少这 是一个原因。设计不只是创造游戏的“最佳构思”;而是在2/3成品(Dynamics和Aesthetics)尚未处于我们的直接控制范围时建构出系列能够落实构思的规则。

体验过程

设计师从Mechanics着手,然后持续跟进,直至它们发展成Aesthetics。你可以把游戏想像成球体,Mechanics是核心,Dynamics包围核心,Aesthetics处在表面。外围内容由深层 内容发展而来。《MDA》作者表示这不是玩家眼里的游戏体验模式。

玩家首先看到表面——Aesthetics。他们也许也会注意到Mechanics和Dynamics,但能够产生直接印象,最通俗易懂的是Aesthetics。这就是为什么即便缺乏游戏设计知识或培训经 历,大家依然能够体验游戏,告知你自己是否玩得愉快。他们也许无法陈述自己为何玩得愉快,或者什么使得游戏“优秀”或“糟糕”,但能够陈述游戏带给他们的感觉。

若玩家在游戏中投入充足时间,他们也许能够把握游戏的Dynamics,知晓自己的体验由此形成。他们也许会发现,他们喜欢或不喜欢某游戏是由于他们同游戏或同其他玩家进行的

某些互动。若玩家在游戏中投入更多时间,他们最终也许能够深入把握Mechanics,获悉Dynamics如何由此产生。

若游戏是由内而外设计而成的球体,那么玩家就是由外而内进行体验。我觉得这是《MDA》的要点之一。设计师创造Mechanics,然后所有内容由此向外发展。玩家体验Aesthetics ,体验向内延伸。作为设计师,我们需知晓这两种游戏互动方式。否则我们很容易创造在设计师看来有趣,对玩家来说非常无趣的内容。

MDA运作实例

我早前曾提到“重生地点”理论,旨在举例说明遵循不同隐含规则的玩家称某些符合游戏技术规则的内容存在“欺骗性”。下面让我们在MDA背景中分析此内容。

在第一人称射击视频游戏中,常见机制是玩家享有的“重生点”——地图上的特定地点,玩家被杀后能够重生。重生点是个游戏机制。这带来此动态模式:玩家靠近某重生点,然 后在某人重生时迅速将其杀死。Aesthetics就会充斥沮丧感,因为玩家想到一重生又会被立即杀死。

假设你在设计新款FPS游戏,你在游戏中注意到此沮丧美学,你希望进行修复,这样游戏就不会如此令人沮丧。你无法简单改变游戏美学,令其“变得更富趣味”——这也许是你的 目标,但这不在你的直接控制范围内。你甚至无法直接改变重生点的机制;你无法告知玩家如何同游戏互动,除非通过游戏机制。所以相反,你需要改变游戏的机制——也许你希 望玩家在随机地点,而非制定区域重生,你希望预期美学效果能够从你的机制变更中诞生。

如何知晓变革是否有效?当然是进行游戏测试。

你如何知晓进行哪些调整,若机制调整的效果无法预知?最后我们会提供些许技巧。目前最显而易见的方法是设计师的直觉。实践越多,所设计的作品越多,进行的规则调整越多 (游戏邦注:然后进行游戏测试,查看变更的影响),你就越能够在发现问题时做出正确调整,有时甚至能在一开始就做出正确调整。经验无可取代,这也是为什么本课程建议大 家进行大量尝试,动手制作游戏。

“若电脑或游戏设计师收获的乐趣比玩家多,那你就犯下糟糕错误。”

现在引用游戏设计师Sid Meier的话恰到好处。他的警告瞄准的是电子游戏设计师,但同样适应于非数字项目。这提示我们所设计的游戏Mechanics和Mechanics也许对我们而言颇具 趣味,但在玩家看来却非常乏味。常见设计错误是创造能够带来乐趣的规则,但这并不一定能够转化成有趣玩法。记住你是为玩家而非自己设计游戏。

Mechanics、Dynamics和Complexity

Checkers from ifreeware.net

通常添加额外机制、新系统、额外游戏物件和新物件互动方式都会提高游戏动态机制的复杂性。例如,不妨比较下《Chess》和《Checkers》。国际象棋包含六种棋子,每颗棋子能 够进行更多操作,这样游戏就融入更多策略深度。

复杂化是好是坏?这要看情况。《俄罗斯方块》非常简单,但依然是非常成功的作品。《班长高级版》虽然非常复杂,但依然取得很大成功。有些游戏过于简单,超过一定年龄层 的用户会觉得其缺乏趣味,如《Tic-Tac-Toe》。有些游戏过于复杂,若其机制能够更加简单和合理效果会更好。

Tic-Tac-Toe from mathlair.allfunandgames.ca

更复杂的机制是否总是会带来更复杂的动态机制?并非如此——在某些情况下,简单机制也能够创造复杂性。而在其他有些情况下,游戏机制相当复杂,但动态机制却相当简单。 评估游戏复杂性的最佳方式是体验游戏。

反馈循环

常出现于游戏,颇值得关注的一个动态机制是反馈循环。这共有两种类型,即积极反馈循环和消极反馈循环。这些术语来自其他领域(游戏邦注:如控制系统和生物学),它们在 游戏中含义相同,但在其他内容则代表不同意义。

积极反馈循环可以看作是强化关系。某事的发生会不断重复,每次重复都得到强化——就像滚雪球,起初在山顶时很小,后来越滚越大,逐步聚集更多雪花。

举个例子,NES有款相当晦涩的射击游戏叫做《嘉蒂外传》。玩家只要获胜,就能够获得特殊玩法模式。在此模式中,玩家会在关卡末尾基于积分获得升级道具:积分越高,玩家在 下个关卡获得的升级道具就越多。这就是积极反馈循环:若玩家获得高分,游戏就会提供更多升级道具,这能够促使玩家在下个关卡中获得更高分,这又会带来更多升级道具。

注意在此情况中,反之亦是成立。假设你获得低分。然后你就会在关卡末尾获得较少升级道具,这样你就很难在下个关卡中获得杰出表现,这意味着玩家可能会获得更低分数,最终玩家落后很多,几乎无法继续前进。

令人困惑的是二者都属于积极反馈情境。这似乎有违直觉;第二个例子非常“消极”,因为玩家表现很差,获得较少奖励,这里的“积极”是指效果在每次重复中日益强化。

游戏设计师应把握积极反馈循环的3大属性:

1. 它们倾向在玩家日益前进的过程中动摇游戏。

2. 它们会让游戏更快结束。

3. 它们强调游戏早期阶段,因为游戏早期阶段的决策的影响会逐步扩大。

反馈循环通常包含2个步骤,但其所包含步骤其实可以更多。例如,某些即时策略游戏包含4个步骤的积极反馈循环:玩家探索地图,这能够让他们接触更多资源,然后购买更优质

的技术,创建更好的单元,然后更高效地探索。就此而言,消除积极反馈循环机制不是易事。

下面是些你或许非常熟悉的积极反馈循环事例:

* 多数“4X”游戏通常基于积极反馈循环,如《文明》和《银河霸主》系列。玩家创建自己的文明帝国后,就能更快生成资源,进而更快成长。待到你同对手真正交锋时,某玩家 通常遥遥领先,使此交锋算不上真正的竞争,因为推动游戏的核心积极反馈循环机制显示,初期领先的玩家将会在未来的游戏角逐中更加遥遥领先。

* 基于建造机制的棋盘游戏,例如《卡坦岛》。在这些游戏中,玩家利用资源提高自己的资源创造过程,使之能够创造更多的资源。

* 物理运动游戏《Rugby》融入小型积极反馈循环:当团队得分时,他们就获得发球的机会,这样得分的机率就更大。因此处于优势地位的团队就能够再次获得有利条件。这和多数 体育运动游戏相反(游戏邦注:在这些运动中,通常刚得分的团队就有没有发球机会)。

Rugby from aflinsider.net

消极反馈循环同积极反馈循环恰好相反。消极反馈循环是种平衡关系。当游戏出现某情况,消极反馈循环会降低相同情况出现的可能性。若某玩家处于优势地位,消极反馈循环会 令对手更容易迎头赶上。

举个例子,想想“卡丁车风格”的赛车游戏《马里奥卡丁车》。在赛车游戏中,若玩家置身车群中,而非遥遥领先或落后很后面,体验将更有趣。因此,这类体验的标准模式是添 加消极反馈循环:随着玩家开始领先车群,对手便会开始采取欺骗举措,寻找更好的升级设备,争取不可能的速度,帮自己迎头赶上。这让玩家更难维持领先位置。这个特殊的反 馈循环机制有时被称作“橡皮筋”,因为赛车仿佛同橡皮筋相连,橡皮筋会将领先者和落后者都重新带回车群中。

同样,反之亦是如此。若玩家落后,他们会找到更好的升级设备,对手会放慢速度,令他们能够迎头赶上。这令已落后的玩家不会继续落后。二者都是消极反馈循环的范例;“消 极”是指动态机制会在每次反复中变弱,无关乎这会给玩家的游戏地位带来积极,还是消极影响。

消极反馈循环也有3个重要属性:

1. 它们倾向稳定游戏,令玩家朝群体中心靠拢。

2. 它们促使游戏耗时更久。

3. 它们强调未来的游戏内容,因为初期决策会逐渐减少其影响。

消极反馈循环的例子:

* 在多数体育运动游戏中,如《Football》和《Basketball》,团队得分后,球就会落到对方手中,他们就会得分的机会。这样某团队就很少会反复得分。

* 棋盘游戏《Starfarers of Catan》包含消极反馈循环,胜利积分少于特定数量的玩家都会在回合开始时得到免费资源。初期这会给所有玩家带来影响,加速初期阶段的游戏进程 。到后期,随着某些玩家开始迎头赶上,超过胜利积分界限,落后的玩家就会获得奖励资源。这令落后的玩家能够更轻松赶上。

* 我祖父是《Chess》高手,比他教出来的孩子还要厉害。为让竞赛更像挑战,他制定这样的规则:若他赢了比赛,下次对手就能在比赛开始移除他的一个棋子(游戏邦注:起初是 一个小卒,然后慢慢变成两个小卒,然后变成马或象)。每次祖父赢后,下个竞赛对他来说就会更具挑战性,他失败的机率就会逐步增大。

反馈循环的运用

反馈循环是好是坏?我们应融入此要素,还是要回避它?正如多数游戏设计要素一样,这取决于具体情况。有时设计师会故意添加促成反馈循环的机制。有时反馈循环在体验中出 现,此时设计师需决定如何处理。

积极反馈循环有其益处。当玩家开始变成赢家时它们就快速结束游戏,防止结局持续很久。另外,积极反馈循环对试图赶上领先者的玩家来说颇为沮丧,他们会觉得自己没有机会 。

消极反馈循环亦能够有效防止初期出现优势策略,让玩家觉得自己还有获胜的机会。此外,它们也会带来沮丧感,因为早期表现较优的玩家会觉得自己因获胜而受到惩罚,而落后 玩家却因表现较差而受到奖励。

从玩家角度看,什么促使某反馈循环机制“好”或“坏”。这存在争议,但我觉得这主要涉及玩家的公平感。若它给人的感觉是游戏有意介入,帮助不配获得帮助的玩家获胜,在 玩家看来此反馈循环就起到消极作用。我们如何知晓玩家如何看待游戏?当然是进行游戏测试。

消除反馈循环

假设你在游戏中发现反馈循环,打算将其移除。你会怎么做?有两种方式。

第一个是去除反馈循环本身。所有反馈循环都包含3个要素:

* 检测游戏状态的“传感器”;

* 基于传感器感知价值觉得是否采取行动的“比较器”。

* 在比较器做出决定后修改游戏状态的的“激活器”。

例如,在先前的卡丁车赛车消极反馈中,“传感器”是指玩家比其余玩家领先或落后多少;“比较器”检测玩家是超越,还是落后某界限值;“激活器”促使对方赛车加速或减速 ,若玩家过于超前或落后。所有这些要素会形成单一机制。在其他情况下,形成反馈循环的机制或许有3个以上,调整其中之一会改变机制的属性。

把握创造反馈循环的机制后,你可以通过移除传感器,改变或移除比较器,改变或移除激活器破坏反馈循环带来的效果。回到《嘉蒂外传》例子(更多积分=更多升级道具),你可 以通过修改传感器,或改变比较器,或改变激活器去除积极反馈循环。

若你不希望移除游戏的反馈循环,但希望降低其作用,另一选择就是添加相反的反馈循环。让我们再次回到卡丁车竞赛例子,若你希望保持“橡皮筋”消极反馈循环,你可以通过 添加积极反馈循环进行中和。例如,当玩家处于领先地位时,对方赛车获得额外速度,也许玩家也能够前进更快,进而出现这样的状况:玩家处于领先能够让整个比赛进展更快。 或者也许处于领先的玩家能够找到更好的升级道具弥补对手的新速度优势。

意外机制

另一游戏设计师需知晓的动态机制是意外玩法。通常意外玩法是指存在简单机制但复杂动态机制的游戏。“意外复杂性”可以用于形容任何存在此属性的机制,即便内容不是游戏 。

游戏以外世界的意外情况:

* 本质来说,昆虫群落(游戏邦注:蚂蚁和蜜蜂)的行为很复杂,它们非常聪明,我们将之称作“蜂巢心智”。事实上,每只昆虫都有自己的简单规则,只有聚集起来,群落才会 呈现复杂行为。

* Conway的“生命游戏”,虽然根据我们的定义算不上真正的“游戏”,但它是模拟细胞生命的系列有序简单规则。每个细胞在当前回合或“生”或“死”。为前进至下个回合, 毗邻0或1个活跃细胞的活跃细胞将死去(过于孤立),毗邻4个以上活跃细胞的活跃细胞也会死去(过于拥挤);死去细胞若毗邻3个活跃细胞将“重生”,在下个回合变成活跃细 胞;毗邻2个活跃细胞的的细胞将保持原状。这些就是全部规则。玩家从最初的选择设置着手,然后修改版面查看所发生情况。然而玩家也会面对相当复杂的行为:结构会移动、变 化和衍生新结构及其他许多内容。

* Boid的“Algorithm”,这是模拟某些CG电影和游戏群集行为的的方式。群落个体只需遵守3个简单规则。首先,若你的一旁有很多同伴,另一旁的同伴很少,这意味着你处在群 落边缘;需朝同伴靠拢。其次,若你和同伴很近,需给它们空间,这样你就不会过于逼近。第三,将自己速度和方向调整成与同伴相似。遵循这3条件规则,你将获得非常复杂、精 细和真实的群落行为。

下面是些意外玩法的例子:

* 在《街头争霸》或《铁拳》系列的战斗游戏中,“组合技能”来自系列简单规则的冲突:随机进攻会吓到对手,这样他们就无法做出反应,也可以在玩家恢复前展开快速进攻。 设计师也许会在游戏中设置组合技能。此惊吓和进攻速度机制创造系列复杂移动,这在系列回合的首次移动后变得不可阻挡。

* 在《Basketball》运动中,“带球”并非规则的组成部分。设计师原本打算将游戏打造成同《极限飞盘》类似的模式:持球玩家不允许移动,要嘛将球投向篮筐,要嘛“传”给 其他队员。没有规则限制玩家传球给自己。

* 《Chess》的开放模式。游戏规则相当简单,游戏只有六种棋子和少量特殊移法,但有很多常见的开放式移法,这会在重复体验中出现。

我们为什么要关注意外动态机制?这通常出于现实原因,尤其是在视频游戏世界,因为你可以从相当简单的机制中获得各种深层玩法。在视频游戏中,需落实的内容是机制。若你 在给某视频游戏编程,意外玩法会带来很棒的玩法时长和代码长度比例。由于这能够明显降低成本,“意外机制”几年前极度风靡,现在我依然会不时听到大家提到它。

值得注意的是,意外玩法不总是刻意设置,因此也不总是令人满意。下面是两个意外玩法的例子,都是来自《侠盗猎车手》系列,其中无意识的意外玩法会带来问题:

* 想想这两个规则。首先,车辆碾过行人会使他们掉落身上的金钱。其次,雇佣妓女会补充玩家的能量,但会消耗资金。从上述两个毫无关系的规则中,我们得到被大家称作“利 用妓女”的意外策略:同妓女共度良宵,然后将其碾过,重获所付出的金钱。这在过去遭受很多流言蜚语,包括有人将此动态机制解读成有意美化针对性工作者的暴力行为。仅表 示“这是意外机制!”不足以向外行人说明这不是有意设计。

* 也许更有趣的是将两个规则结合起来。首先,若玩家给无辜旁观者带来伤害,他们会通过进攻玩家保护自己。其次,若车辆遭受严重损害,它最终会爆炸,破坏周围的东西(游 戏邦注:当然也会波及司机)。这会带来如下非常不真实的场景:玩家驾着破损的车辆撞击大量旁观者。然后车辆爆炸。玩家从废墟中爬出来,苟延残喘,然后附近的“撒玛利亚 人”群落认为玩家损及他们,结伴来到地面,解决玩家!

正如你看到的,意外机制不总是好事。更重要的是,制作包含意外机制的作品成本不低。由于动态机制的复杂本性,相比机制和动态机制存在简单关系的游戏而言,意外模式游戏 需要更多测试,更频繁更新。融入意外机制的游戏更易于编程,但更难设计;这无法降低成本,而是将原本由程序员承担的费用转移至游戏设计师身上。

从意外机制到有意设计

玩家意图,从某种程度上,看同意外机制相关。通常我们能够基于系列小型简单相关系统获得意外机制。若玩家能够弄清这些机制,有意将其设置成复杂连锁事件,也是获得深刻 玩家意图的渠道之一。

推荐阅读

* Clint Hocking的《Designing to Promote Intentional Play》,这是Clint 2006年在GDC所做的现场演讲。

所获经验

本文的要点是游戏设计不是琐碎任务。这项工作颇具难度,主要由MDA的性质决定。设计师创造规则,规则创造玩法,玩法创造用户体验。每个规则都会给玩家带来双重间接影响, 这难以预测和控制。这同时也说明为何小小的规则调整会带来波及效应,严重变更游戏的体验方式。但设计师的任务是创造受人喜爱的用户体验。

这就是为什么游戏测试如此重要。若你对规则调整感到不确定,这是测试其效果最有效的方式。

迷你挑战

分析你最喜欢的体育游戏,查看其中的积极或消极反馈循环。多数运动都至少包含一种循环。然后试着调整规则,消除此循环。

谈论这个话题的第一个原因是我们将在后面的课程讨论“趣味性”的整体概念,以及如何让游戏更加有趣。对于绝大多数游戏设计者来说,这是他们的最高指导原则:制作一款游 戏并让它变得有趣。所以,在我们进一步深入这个原则之前,我想要先澄清,趣味性并不是游戏设计的唯一目的,事实上,一些游戏即使不具备太多特别的“乐趣”,也能够按照 设计目标而取得巨大成功。

其次,作为一个持续多年的争论,我希望让那些新进入这个圈子的人也能够快速了解到这个争论的基点。许多设计者总是会不时拿起这个话题说事,而且我也想有些设计新手也应 该试着进入这个争论圈中。

再次,那些所谓的“艺术游戏”——也就是那些以艺术表达(而非娱乐)为主要目的的游戏已经越来越多了。现在,在这个领域中有许许多多非常有天赋的人正在制作着一些很有 趣的东西。很多艺术游戏其实都很简单,且规模较小,且通常是一个人在非常短的时间内完成的作品。还有许多潜在的方法有待挖掘。而这点刚好让艺术游戏能够提供给那些想要成为游戏设计者的人们更好的机遇。

最后,我深知艺术历史和艺术评论是一块很危险的领域。因此,我在某种程度上受到激励,而着重从个人兴趣这块进行阐述,尽管我不得不承认,讨论这个话题会给我带来一定的 麻烦。

What_is_art(from pedrohbv.deviantart.com)

什么是艺术?

就像你所看到的,《Understanding Comics》是一本关于漫画书艺术形态的漫画书。如果你阅读了该书的第7章节,你将会立刻发现漫画书艺术与游戏设计的相似之处,除了公众普 遍意识到的“非严肃”和“针对于儿童”这两个问题。

McCloud(游戏邦注:《Understanding Comics》作者)开始尝试将“艺术”定义为一种与生存或繁殖无关的内容。我曾经交流过的大多数学生都认为这个定义太过广泛,但是却很 少有更好的定义了。事实上,如果你接受了这个定义,那么“游戏是艺术”对于你来说便不再是一个难以解决的问题,毕竟,当你真正花心思去完善下一款《生存之旅》的关卡, 或者考虑着将你的下一款游戏定义为象棋这类型的游戏,那么你也许就不用费心思去处理现实世界中的生存或繁殖问题了(除非你设置了不一样的游戏玩法)。

我曾经听过有人将艺术与交际性和多变性联系在一起。虽然这个定义的面也很广但是却也清晰地将游戏涵括在内。

Dictionary.com(词典网)根据美学原则,即什么是好看,且具有吸引力与特殊意义的判断方法,将艺术定义为特性,产品,表达或者领域。如果按照这个定义,那些充满着“花 瓶角色”或者具有各种突出因素的游戏,也都能够被定义为艺术。

维基百科将艺术定义为过程或者一件具有吸引力的产品。如果游戏具有这些形式要素,那么设计者便可以基于这些要素去设计游戏。显然地,如果游戏能够影响人们的感觉,那么 定是基于它们的视觉特性而非其它属性。游戏同样也能够影响人们的情绪——来自电子游戏领域两大典型的例子便是《Planetfall》中Floyd之死以及《最终幻想7》中Aerith身亡,尽管人们也可以从电视在的体育比赛,以及桌游《Diplomacy》中朋友和爱人的离开而感受到相同的情绪。

其实我的意图并不是定义艺术这个词本身,因为这与定于游戏这个词一样困难,且一般都是徒劳的。而是我认为不论你认为该如何定义“艺术”,都不难发现在游戏都在这些艺术 的定义范围之列。

为何会存在这个问题?

如果游戏符合任何“艺术”定义,那么我们就应该想想为何这仍是一个备受争议的话题。为何仍有人认为“游戏不是艺术”?

在这里我们最好能够区分早前朴素的“艺术”以及较为华丽的“纯艺术”或者“高端艺术”的区别——这种永恒的艺术总是能够传达出人类体验的本质内容。莎士比亚,达芬奇, 莫奈都是在创造这种类型的艺术。但是,这个论据并不是在说游戏不是一种“艺术”,从某些意义上来看游戏也是经过有目的性雕琢的一件艺术品,但是因为游戏媒介中的一些内 在因素,它达不到“高端艺术”的标准。

对于这点我不想加以描述,主要是因为育碧设计师Clint Hocking在《On Authorship in Games》中已经详细描绘了这一内容。

无论如何,只要你注意到我所列出读物的共同主题,你便能够看出我的个人观点。也许我们的游戏不能像“蒙娜丽莎”或者电影《公民凯恩》那般伟大,但是这同时也是一种机遇 。所以我们暂且跳过这个话题。让我们假设游戏是艺术表达的一种有效媒介,并开始讨论如何去传达这种艺术。

6大步骤

关于《Understanding Comics》我想提及两大关键点,首先便是 McCloud关于艺术的定义,如上文描述道的。而其次就是以下关于艺术的六个层面内容:

观点/目的。要传达什么信息,要表达故事中的哪些想法?为什么你想创造一件艺术品?

形式。你将使用何种艺术媒介去传达你的信息?油画?雕塑?形意舞?漫画书?游戏?

习语。McCloud说习语,如果牵扯到游戏,更常被称为类型。而这些类型包括第一人称射击游戏,即时战略游戏,汽车模拟游戏,大型多人在线角色扮演游戏等等(或者桌上游戏, 如资源管理游戏,追踪游戏,细节游戏,骰子游戏,铺砖游戏,赌博游戏等等)

结构。在故事中,结构包括基本情节,角色以及其它建筑模块。在游戏中我们称其为“核心机制”。是哪一些结构部件组成核心的用户/观众/玩家体验?

工艺。在漫画书中,这点包括一个故事的表达是否合适。而在游戏中,工艺是指如何让游戏规则和玩家体验更加合理与自然,也就是比起应付繁琐的规则,玩家可以更加轻松地享 受游戏乐趣。

外观。这是指外部体验,如颜色,音效,图形,美丽,以及那些立刻可以察觉到的细节。也就是所谓的“花瓶角色”。

McCloud注意到忠实的漫画书读者会从外到内真正地体验一部作品。先是看到表面,然后往深层次去感受故事。更进一步看来,你甚至可以掌握到故事背后的真谛,并从内心深处感 受艺术家的创造性,即使这个故事并没你想象中那般优秀。甚至,当对故事做进一步研究时,你还会找到不同类型之间所存在的差别,并理解为何在一个类型中会出现一些特定的 故事元素或者其它管理等。看得越深,你便能够鉴赏漫画书的媒介,并理解它与其它艺术形式的不同之处,从而你便能够了解一部作品背后的真理,以及真正长久的文学作品的真 正目的。

你也许会发现这些同样也适用于游戏中。

McCloud同样也注意到了,当一件作品是“从外向内”进行设置时,它同样也会创造出“从内向外”的表达——在设计之前,而创造者必须在一开始就选择并明确一种模式,从而从 中选出最适合的类型。创造者既能够慎重地做出选择也能够情绪化地进行选择,但是不管怎样他们都需要最先考虑这个问题。随后定义结构,然后精心地雕琢所有的细节,最后便 创造出了外观。

MDA(from girlzinweb.com)

是否这听起来很耳熟?的确,从很多方面来看,这是对于MDA Framework(游戏邦注:MDA是chanics/Dynamics/Aesthetics的简称)的重述。

而我认为McCloud的6大步骤是MDA的延伸。MDA中的Mechanics就等于McCloud口中的结构;Dynamics则与工艺类似;而Aesthetics也就是外观。虽然它们并非完全相同,但是却真的 很相近。在这两个例子中,用户都更加关注于外观,而真正的艺术家则更加注重于艺术过程中的内部核心要素。

面向艺术的过程

如果MDA代表一件艺术品的外部三层,那么又有什么才能体现内部三层呢?为了回答这个问题,我们需要再次转向McCloud的范例中。

继LeBlanc等人之后,McCloud采取了另外一个重要步骤。他声称不论是从外到内的体验以及从内到外的创作,艺术家及其他创作者都会遵从从外到内的学习方法。

仔细想想,什么才是对游戏有帮助的“最佳创想”?可能是与你喜欢的一款游戏有关的外部特征。“就像是《吃豆人》遇见《太空入侵者》。没有最好只有更好!”很多人都是通 过“修改”自己喜欢的游戏,改变现有的游戏设置或者一些外部特征,改变游戏中的角色外表等等,而不是像游戏《Marines Shooting Aliens In Space》,变得越来越山寨 《Wizards Battling Dragons In The Mountains》了,因为它们拥有相同的mechanics,相同的dynamics以及不同的外观。

随后会怎样?也许你会玩许多游戏,而发现许多同样带有龙,火球以及巫师等角色的游戏也有好坏之分,而它们间的差别并不是来自于故事或者类型,而是来自游戏设置。随后你 便开始思考不同的游戏类型,以及哪种类型有趣而哪种无趣。经过进一步的体验和学习你将会知道什么样的机制才能够创作出吸引人的游戏设置。也许这正是你们所想要的,即为 了成为一名优秀的设计者,你可以参照一些已经建立的有趣类型而制作出属于自己的有趣游戏。

但是如果你着眼于过去,你也许会问:这些类型来自于哪里?是谁决定特定的核心机制可以在游戏内部进行相互仿效,难道只有这样才能创造出优秀的游戏设置?如何才能创造出 新的类型?是否这是一个前人从未尝试过的过程以及前人从未发现的优秀机制?而你可以创造出一个甚至是多个新游戏类型。也许你可以或者不能够创造出这种类型并尽可能地完 善它们,但是你的创造却能够让更多人参考你的作品外观,使用你的核心理念并不断进行完善。

你能做的就只有这些?当然远远不止了。你肯定会好奇还有些什么,首先你可以从两方面进行摸索:观点和形式。

当你在探索形式内容时,你将会触及媒介的界限。游戏能够做些什么?它们是否能够影响玩家的情绪(除了让他们感到兴奋并带给他们幻想)?比起其它艺术媒介什么内容更适合 在游戏中得到体现?你要如何使用之前从未被使用过的媒介(不只是新的游戏类型或者新的有趣的方法)去表现游戏?你是否能够改变别人的想法?是否能够改变别人的生活?你是否能够做到图画或者电影所做不到的触动?怎么做?随后你可以创造一件实验作品,可以说一款非常小的游戏,然后借此探索游戏作为一种媒介可以做什么以及不可以做什么。 也许这些实验游戏并不有趣或者不能够吸引广大的用户,但是对于那些在形态游戏媒介中工作的人们来说,这却有很大的帮助,因为他们以你的实验作品为参考,并进行适当修改 而用于表达他们自己的观点。

而如果你在探索观点或目的,比起向世界传达一则信息,你必须选择游戏作为你的最佳表达方法。在此,你所面临的挑战是传达媒介是玩家所控制的体验而非设计者。为了让游戏 设置更有意义,你应该尝试一切可能的方法。我们想要表达哪些观点?在你的生活中存在着哪些深层意义是你想要与别人进行分享的?

问题很多,答案却很少…

如果关于上述的那些问题我都能够答出详细的答案,那么你肯定会惊讶不已。但是事实上我并未这么做,一方面也是受到艺术本身的性质所影响。

这个课程主要是关于游戏设计艺术的外部三层内容:Mechanics,Dynamics以及Aesthetics(如果你愿意的话,也可以说是结构,工艺和外观)。教授你如何通过创造规则去制作出 吸引人的游戏这方面内容已经花费了我们大量的课程讲述了;而教会你如何创造出新类型或者触及媒介边界这些内容仍将需要我们投入更多的时间。

但是除此之外,就像McCloud所说的,关于内部三层内容我们并不能简单地从课堂上或者书籍上学习到。为了能够理解艺术形式中的内部核心,你将需要花费你的整个职业生涯,也 许是20年或者30年或者更多,独自进行研究。但是前提是你愿意这么做。如果你没有兴趣,也没关系。这个世界需要更多人去实现游戏变成艺术媒介的这一过程,但是这个世界上也仍需要优秀游戏的存在。而你必须知道到底需要花多少时间才能实现艺术目标。虽然我没有义务去告诉你们答案,但是你自己必须对此有所规划,才能在未来的前进道路中更加 顺畅。

艺术的历史

这个部分总是让我很烦躁,因为很多人对当代艺术持着怀疑的态度。一些人只是捣鼓着一些自认为是艺术品的垃圾,就大言不惭地称自己为“艺术家”,并且将所谓的“艺术品” 卖给美术馆而挣得2千欧元。这就是艺术?如果是,难道这就是游戏所追求的目标?这样做能够帮助我们退一步看待问题,并衡量我们是如何走到这一步,因为游戏很好地适应了当 代艺术,而我们也应该理解其中的原因。

让我们穿越回文艺复兴时期,而油画也正是在这个时期开始被当成一种艺术形式。那时候,艺术被认为是对于世界的真实表示;而图画则是一个窗口能够帮你找到现实的归宿。如 果一名艺术家能够更接近现实地去描述一个场景,那就说明他足够优秀。判断艺术的标准就是判断一幅画是否逼真,所以很简单!随后,大约在20世纪90年代的时候,照相机出现 了,也因此破坏了这种判断标准。

现在,因为照片可以100%原景再现,所以过去的艺术形式也就逐步被淘汰了。对于画家来说,他们不得不问自己一个问题,也就是现在的艺术形式到底是什么?

Wassily Kandinsky(游戏邦注:俄国画家,表现主义的创始人)也开始自问,艺术对于自己来说是一个目标,还是只是某些事物的代表:帆布只是一个“屏幕”而不是“窗户”或 者“镜子”?而因此出现了我们现在所说的抽象艺术,这时候艺术不再是代表自己的一种标志了。

你要如何判断这种类型的艺术?这时候你应该如何去告诉那些充满才能和灵感的艺术家这个现实,那些只会随意地在帆布上涂鸦的装腔作势者甚至也能够得到许多没有道理的赞许 。

具有影响力的批评家Clement Greenberg提供了一个解决方案,即单纯依据审美价值去判断艺术。技术执行是真理。艺术家是创造者,而一部好的艺术作品将会提供给任何人相同的 审美价值。Greenberg将所谓的“现代艺术”进一步现实化(游戏邦注:这里所说的现代是指从1910年到1950年期间这一特定年代,而不能与现今的当代艺术相混淆)。

在未来十年里,艺术世界将会脱离Greenberg口中的形式主义,而坚持艺术将从被动转变到互动;变成艺术家与观众之间的对话;艺术将会做出更多的诠释;艺术将会带有实在的意

义。而这个时代的艺术被称为“后现代”艺术。

特别是在20世纪6,70年代期间,艺术碰到了一个潜在的问题:艺术变成了最热门的商品,而艺术家的身价也瞬间暴涨。仍然还有很多艺术家认为自己的艺术品大大贬值了,因为比 起交易,他们创造那些艺术品是出于其它目的,没想到却被当成了商品进行销售。反倒是艺术品的含金量远远低于创造者的名字了。虽然这种情况能够帮助那些艺术家们赚到更多 钱而过上更高质量的生活,但是这其中的代价却是“出卖”他们的作品……但并不是所有艺术家愿意向这种情境妥协。

那么游戏呢?是否这些内容听起来都似曾相识?我们又该如何判断游戏?如果用数字作为评价标准,按照技术执行来看,对于音频或者图像的临界赞许,游戏的乐趣可以按照1至5 的分数进行评判,而预示着那些对于观众来说有趣的内容对于所有读者来说也很有趣。如果按照游戏评判的现实状况来说,其实也就等同于Greenberg的形式主义。好像我们陷入了一个诡异的时空隧道中,被带回1930年的那个时代里。那么游戏是更偏向于现代艺术还是后现代艺术?是被动还是互动?游戏会针对于不同的个人而创造不同的游戏体验还是提供 相同的游戏体验给所有人?游戏只能体现出视觉效果还是能够在机制中嵌入更多深层次的意义?也许你有不同的见解,但是在我眼中游戏更像是后现代艺术形式。我希望在不久的 将来,游戏观众们能够从这个视角去看待游戏。

收益又是怎么样的一种情况?游戏完全陷入了我们所说的商品化“问题”中了。每年电子游戏产业的盈利都会增长近2百亿美元。虽然在桌面游戏产业我找不到相关数据,但是以《 Scrabble》和《大富翁》每年的销量来看,我们不难想象这也是个丰收的产业。如今,绝大多数游戏工作室制作游戏的目的都是为了赚钱,而有时候开发者便不得不在制作独特游 戏与制作有利可图的游戏之间相互妥协了。

简单地来讲,如果你对这个领域感兴趣,那么你便可以花点时间来了解艺术历史。艺术评论家以及艺术历史学家的世界中已经明确了如何去判断“艺术”,追溯到1917年,当杜尚 (游戏邦注:法国艺术家,被誉为“现代艺术的守护神”)在一个尿壶上签上自己的假名后,他便称其为一件艺术。事实上,很多开发者都认为艺术世界太过势力,所以拒绝承认 游戏属于艺术范畴,但是这只是他们的片面想法;实际上,游戏被艺术评论家所注意到了。我自己的首部文献研究出现在1994年(而这一年刚好是PlayStation问世的前一年)。在 我能够找到的所有案例中(也就是所有同行评议的学术文章),不仅对电子游戏进行了分析,而且也含蓄地暗示了游戏是一种艺术形式。我也未曾找到一篇文章会浪费大把时间去 捍卫游戏的艺术表达形式,所以这只是一种先验假设。让我们克服这种迫害妄想,然后开始制作艺术游戏。

什么是艺术游戏?

要如何才能制作出一款以艺术表达为目的而非趋于娱乐的游戏?这就必须取决于“艺术”的含义了,而显然已经有许多游戏已经处于一种表达形式中了。你将会看到,这些游戏会 分为几个类别。也许还有其它类别我未在这里提及可能因为那些游戏的艺术性受到质疑,或者因为那是未被触及的一些领域。但是我所列出的这些类别将帮助你更好地认识所谓 的艺术游戏。

我将列举出一些典型的游戏。如果条件允许的话你可以尝试看看。然后再做进一步讨论。这些游戏的游戏时间都很短,一般维持在几分钟之内,5分钟或者更短。也有一些较长的游 戏,能够让你马上意识到游戏的大意,然后你便可以判断是否继续游戏。如果你有足够的时间,请试试这些游戏。

体验游戏

Jason Rohrer的《Passage》以及/或者《Gravitation》(分别游戏时间是5分钟和8分钟。)

Rod Humble的《The Marriage》(只需要几分钟游戏时间。)

Rod Humble的《Stars Over Half-Moon Bay》(只需要几分钟的游戏时间。)

Gonzalo Frasca的《September 12》(游戏时间不确定,但是玩家可以在短短1,2分钟内就知晓游戏机制。)

Amanita的《Samorost》(游戏时间很短。)

Jenova Chen的《Cloud》(游戏时间很短,但是在第一个关卡你便能够知晓主要的游戏机制,或者只需花费你几分钟的时间。)

经验教训

我想,关于游戏是否是“艺术”这一争议还会持续很长一段时间。对于我们而言,这是一种无意义的争论,但是如果你很想要通过游戏媒介而进行艺术表达,那这种争论对你来说 就非常有意义了。

对于游戏设计者来说,学习艺术和艺术过程非常有用。如果你想知道在这个课程结束后你还可以做些什么,一个潜在的方法便是你可以进一步探索设计的内在意义。

尽管你并不是所谓的大师级人物,你也能够创造出具有艺术感的作品,并且通过创造过程更清楚地理解艺术和艺术家的定义。就像Koster在《Theory of Fun》中所说的:

“最重要的是,游戏和它们的设计者必须认可艺术和娱乐的相互联系,所有的艺术和所有的娱乐都在给观众出难题。但是所有的艺术和所有的娱乐也都在帮助我们理解一些混乱的 局面。艺术和娱乐不应该用‘类型’区分,而应该用‘强度’进行识别。”

关于那些游戏……

我们可以从一些关于艺术的讨论中找到游戏的影子,因此我们能够从中找到一些线索而通过游戏设置去创造属于我们自己的艺术表达。我想在此陈述,以下内容都是我的个人见解 ,而你们也许会有不同的观点。我不认为意见不同有什么不好,因为后现代艺术允许我们从不同层面不同角度进行理解。

samorost 2(from samorost2.com)

《Samorost》从视觉上看来就是一种“艺术”。它就像是一种具有交互性的画作:非常欢快的图像以及很棒的探索模式。创造者希望能够得到来自于玩家们的特别视觉反馈。

而《Cloud》进一步落实了这一点,它故意在观众的心里创造出一种情感回应(特别是当玩家们在盯着云朵时的那种天真烂漫)。我的一些学生发现这个部分实践起来过于困难,所 以我便告诉他们,这是一个探索的过程,只是在尝试着回答游戏是否能够引起情感反应而已,所以不用太过执拗于这个过程而将其过于夸张化。

《Passage》和《Gravitation》都传达出了一种特别的观点或者感觉(。Rohrer尽最大的努力将自己的情绪直接体现在游戏设置中。而这两款游戏与《Cloud》的区别就在于后者的 目标是创造一种情感,而前者则是创造者情感的自我表现。

《The Marriage》与Rohrer的游戏一样,但是前者比起情感,更侧重于表达观点(特别是Humble总是花大把的时间去刻画游戏机制)。

《September 12》同样也在传达一个观点(主要在说明残酷的战争是错误的),但是它却未进一步拓展这个观点。当Humble和Rohrer都在用游戏表达艺术家的观点和情绪的同时, 《September 12》则在尝试着说服自己的观众。所以这不是一种探索,而是一种修辞,着重在目的上凸显于其它作品。

《Stars Over Half-Moon Bay》与《The Marriage》一样也是在表达一种观点(它是在陈述一个创造性的过程,即当一开始是晴空万里,但你进入这个神秘的创造过程后所有的一 切是如何瞬间阴暗下来,最后当一切都再次明朗之后你又是如何创造出永恒。)游戏设计者和艺术家都在为了创造过程而努力,《Stars Over Half-Moon Bay》比起《The Marriage》更加“多元化”。理论上《The Marriage》会帮助那些想要了解长期关系的玩家解答答案,而《Stars Over Half-Moon Bay》则会直接告诉玩家其他设计者正在挑战他 们的游戏。

如果按照McCloud的6大步骤去理解这些游戏,我们可以看到一些新型模式。以下是关于艺术游戏的一些潜在出发点:

把游戏当成是自我表现(“观点/目的”)的一种媒介。你也许是在表达一种感觉,一个观点或者一种意识形态。或许你只是想借此表达你自己,或者说服观众认可你的某些看法。 对于情绪表达,从MDA中的“Aesthetics”说起,逆向来看:你希望玩家感受到何种情感,什么样的“Dynamics”能够诱发这种情感,以及最后什么样的“Mechanics”能够创造这 种情感?对于观点表述,你要始终记得游戏是一种系统,所以你需要找到你想要表达的观点背后的那些系统,然后找到这些系统内部的游戏设置。

利用游戏去探索“游戏作为艺术媒介”的局限性(“形式”)。我们先从一个问题说起:游戏能否做到X?(不论所谓的“X”是什么)然后去设计一款游戏并尝试着做X,以回答这 个问题。

创造一件传统的艺术品,带有交互式游戏因素(“外观”)。在这里,你的创造过程也许与游戏设计不同。

是否还有其它艺术品能够实践其它步骤?我认为答案是肯定的,但是我们还未完全找到它们。

家庭作业

今天我提供了一个关于设计的选择,但却不是基于体验级别(我不得不承认,我们中的许多人在这个领域还是新手,尽管我们的身份是游戏设计者),而是出于兴趣。这里有四个 选项,是受到《Challenges》章节末尾的“非数字短游戏”的启发:

选项1(创造情感):设计一款非数字游戏将能够帮助儿童理解什么是悲伤。同样也带有规则和游戏所需组件。如果需要的话,也必须包含你是如何解决这个问题以及为何你认为你 的游戏能够(或者不能)获得成功。

选项2(劝导):修改桌面游戏《RISK》而进一步倡导世界和平。按照最初所确立的规则去看待你所做的改变。如果需要的话,也可以适当评价你所付出的努力,不论它们是否成功 ,并思考原因。

选项3(探索游戏的界限):故意设计一款规则不完全的游戏,并要求规则制定者在游戏期间不断完善规则,从而让游戏实现可玩性。公开你的(不完整)规则。

选项4(探索媒介的本质):选择一款你认为具有艺术性或者能够鼓舞人心的数字游戏。为一款非数字版本游戏创造规则。注意不同的媒介会如何影响游戏体验,思考什么样的艺术 观点是数字或非数字形式的最好表达方法。公开你的规则和评论。

决策

Costikyan在《I Have No Words》中指出,我们用这个热门词“交互性”形容我们真正所指的“决策”。所谓“决策”,本质上是指玩家在游戏中的所做所为。如果没有这些决策 ,那么游戏就不再是游戏了,只不过是电影或其他线性活动罢了。完全不具有“决策”的游戏主要有两个例外:某些儿童游戏和赌博。关于赌博,没有决策是合情理的。赌博的“ 乐趣”在于可能赢钱也可能输钱的刺激感;如果没有这种刺激感,那么大多数赌博瞬间失去所有乐趣。在家筹码玩赌博游戏时,你玩的扑克牌包含了真正的决策成份;如果跟钱无 关,可能也没什么人会去玩掷骰子或老虎机了。

你可能会好奇,儿童游戏完全缺乏决策是怎么回事?我们就稍微谈谈吧。

除了那两个例外,大多数游戏都有一定的决策方式,且游戏的乐趣会因此受到或多或少的影响。Sid Meier曾表示,好游戏就是一系列有趣的决策(大概就是这个意思吧)。这个观 点有一定道理。但什么能让决策“有趣”?《战舰》是一款包含大量决策的游戏,但对成年人来说,不算特别有趣,为什么呢?为什么《卡坦岛》中的决策比《大富翁》中的更有 趣?最重要的是,怎么给你自己的游戏设计出真正吸引人的决策?

禁忌

在描述什么是好决策以前,我们有必要先认识一些不太有趣的决策。注意,下面用到的术语(明显的、无意义的、盲目的)是我自己想的,不是行话,至少目前还没有“官方”承

认。

无意义的决策大约是最糟糕的一种:玩家有选择可做,但对游戏玩法不产生影响。如果玩家出哪张牌都一样,那也不算存在选择吧。

明显的决策至少对游戏有所影响,但如果正确答案太过赤裸裸,其实也不算有选择。在桌面游戏《RISK》中的掷骰子就属于这一类:如果你受到3名或以上的敌人攻击,你可以“决 定”是否掷骰子1次、2次或3次……,但最好的显然是3次,所以除了非常特定的情况,其实没有多少决策可做。《Trivial Pursuit》中有一个更微妙的例子。每一回合,玩家将面 对一道很琐碎的问题,

如果知道正确答案,那么你就要决策了:说出正确答案或不说出来。如果玩家知道答案,凭什么不说出来呢?游戏的乐趣就是向别人展示你对生活中的鸡毛蒜皮之事多么了如指掌 ,而不是掌握了一套高明的决策技巧。我认为,这也是为什么《Jeopardy!》这种问答秀节目看着比玩着更有意思。

盲目的决策对游戏有影响,答案也是不明显的,但存在另一个问题:玩家没有足够的知识信息做决策,所以只能随机做决定。“石头-剪子-布”游戏就属于这一类。你的选择会影 响游戏结果,但你没有办法有根有据地决策。

以上决策,很大程度上,并没有多少乐趣,至少不算特别有趣,基本上是在浪费玩家的时间。无意义的决策可以删除;明显的决策应该自动实现;盲目的决策可以随机化,且完全 不必对游戏的结果产生影响。

现在看来,我们很容易就明白为什么那么多游戏并不是特别吸引人。

Trivial Pursuit(from touchgen.net)

想一想这款通俗问答游戏《Trivial Pursuit》。首先,你把骰子投向任意方向,所以你要落在哪里就构成了一个决策。在游戏面板上,有助于取胜的空间并不大,所以你要尽可能 落在其中,这是一个明显的决策。如果你不能,你的选择一般就取决于你最擅长的那个问题分类,这又是一个显然的(游戏邦注:或盲目的,在做出选择以前,一定程度上你并不 知道你在各个分类中会遇到什么问题)决策。一旦骰子停下来,你的琐碎问题就出来了。如果你不知道答案,那就没什么决策可言了;如果你知道正确答案,那么你要决策的就是 说出来还是不说出来……但没理由不说啊,所以这又是一个明显的决策。

再来考虑一下我们老提到的桌面游戏《战舰》。这款游戏的所有决策都是盲目的。游戏没有给你任何决策信息,所以你不知道向哪开火。如果你恰好击中敌方的潜艇,你确实有了 一些信息,但你仍然不知道战舰的方向(横向或纵向),所以玩家的下一次决策仍是勉强的,只是盲目的成分稍策少了一点罢了。

《Tic-Tac-Toe》这款游戏有些有趣的策略,不过,那是在你掌握游戏和意识到百战百胜的方法以前。之后,所有决策也将变得显而易见。

好决策?

既然我们知道什么是“坏决策”了,那么要回答什么是“好决策”也简单了。不过,我们还要再深入一点。一般来说,有趣的决策与交易有关。也就是,你得有所放弃才能有所收 获。这种交易可以有多种不同的形式。以下我列举了一些例子(我用的仍然是我自创的术语):

资源交易:你放弃一种以换取另一种,且二者皆有价值。哪一个更有价值?这是一个价值判断,玩家的能力是否能正确判断或预期价值决定了游戏的结果。

风险与回报:一种选择是安全的;另一种选择可能有更高的回报,但也有更高的风险。你选择安全的那个还是危险的那个?部分取决于你对回报的渴望程度,另一分部取决于你对 安全和风险的分析。你的选择,再加上一点儿运气,决定了结果。但因为选择的数量是相当充足的,所以运气的成分影响不大,获胜的往往还是技巧是更胜一筹的玩家。(推论: 如果你想在游戏中增加运气的份量,最好的办法就减少决策的整体数量。)

行动的选择:你有若干你可以做的事,但你不能同时全都做。玩家必须选择自己觉得最重要的事做。

长期与短期:你有些事必须马上做,或者稍后再做。玩家必须平衡当即需要与长期目标。

社交信息:在游戏的世界中,欺骗、交易和背后中伤都是充许的,玩家必须在诚信与欺诈中作出选择。欺诈可能在当前境况下有利可图,但导致其他玩家以后都不想跟你交易。暗 箭伤人可能会在现实世界里产生消极结果。

两难困境:鱼和熊掌不可兼得,你能承受损失哪一个?

注意这里的共同思路。所有这些决策都涉及玩家对事物的价值判断,价值总是在转移并且不总是肯定的或明显的。

下次你玩一款确实喜欢的游戏时,注意一下你在做哪一种决策。如果你有什么特别不喜欢的游戏,就思考一下你在游戏中做的是什么决策。你会发现自己在游戏中的决策偏好。

动作游戏?

这会儿,你大概想知道,以上有多少条可以用于FPS游戏?毕竟,当身处枪林弹雨之中,小命都快顾不上了,谁还能想到权衡资源管理什么的呢?

简单地说,此时玩家在游戏中做的也是相当有趣的决策,且实际上决策的速度比平时快得多——通常每秒钟就要决策几次。为了缓和时间紧凑带来的难度,此时的决策往往是相当 简单的:开火或躲避?命中或移动?闪避或跳跃?

时限可以用来把一个明鲜的决策变成有意义的决策。我个人偏好的另一个说法是:时限让人变傻。

情绪决策

还有一类决策有必要考虑一下:能影响玩家情绪的决策。在《Far Cry》中, 是救同伴(使用你宝贵的资源)还是让他自生自灭,这是一种资源决策,但也是情感决策——这与现 实战场上的决策一样,但现实中还要分析可用的资源和可能性。与此类似,绝大多数玩家不会带着“道德选择就是有害的”这样的想法来玩游戏(《Knights of the Old Republic 》或《神鬼寓言》)——不是因为“有害的”是次等策略,而是因为即使是在虚拟的世界中,许多人也不能无动于衷地看着无辜者被拷打或残杀。

再来思考一下许多桌面游戏的开头部分普遍存在的决策:己方是什么颜色?颜色通常只是为了区分面板上属于不同玩家的对象而设置的,对游戏玩法本身并无影响。然而,不少人 都有自己最中意的颜色,玩游戏时总是坚持使用“自己的”颜色。如果两位玩家都“总是”玩绿色,碰上了免不了要为谁用绿色而争吵不休,那就有意思了。如果玩家的颜色对游 戏玩法无影响,这就是一个毫无意义的决策。然而事实上,玩家却矛盾地发现这种决策还是有意义的。理由是,玩家对结果有一种情绪上的寄托。当然,作为设计师,应该意识到 玩家会在情绪的影响下做出什么样的决策。

“心流”理论

我们来讨论一下这个难懂的概念“乐趣”。游戏应该有乐趣。游戏设计师的作用大多数时候就是让游戏变得有趣。请注意,当我提到“乐趣”一词时,我总是故意把它带上引号, 因为我认为这个词对游戏设计师来说并不特别有用。我们天生就知道什么是有“乐趣”,这是肯定的。但这个词没有向我透露过应该怎么制作“乐趣”。什么是“乐趣”?“乐趣 ”从哪来?什么让游戏有“乐趣”?

有趣的决策看起来好像应该有“乐趣”。是这样吗?不见得,为什么这类决策是有趣的,或为什么不有趣的决策对孩子们来说仍然有趣,对这些问题我们还没有解答。所以我们来 看看Raph Koster怎么说的吧。

Raph Koster的《Theory of Fun》是这么说的:游戏的乐趣来自技能的掌握。真是激进的论断呢,因为这个说法把“乐趣”与“学习”给等量齐观了……至少我没长大时,我总是 习惯性地把“学习”与“学校”挂钩,“学校”当然没什么“乐趣”可言。所以,这个理论有必要稍作解释。

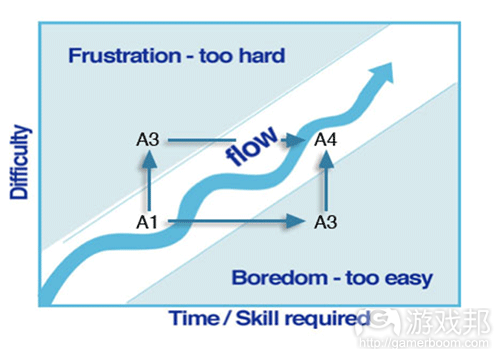

《Theory of Fun》大量提到心理学家Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi的研究成果,即情绪的“心流”(flow)状态。当人处于这个状态时,将会对着某事物全神贯注,心无旁骛,效率 也会非常高,另外你的大脑会产生一种使你愉悦的神经化学物质——“心流状态”只是书面上的说法。

Csikszentmihalyi认为达到“心流”状态必须具备3个要求:

1、你所处的活动具备挑战性,需要一定技能;

2、活动有明确的目标和反馈;

3、结果是不确定的或受到你的行为的影响。(游戏邦注:Csikszentmihalyi称之为“控制的悖论”:你能控制自己的行为,从而间接控制结果,但你不能直接控制结果)以上要求 是有道理的。为什么你的大脑需用排除所有外界干扰,精神高度集中于眼下的活动才能进入“心流”状态?因为只有这样,你才能完成任务。“心流”状态影响成败需要什么条件 ?

你必须有能力用自己的技能(针对目标)影响活动。

Csikszentmihalyi还提出了“心流”状态的5个效果:

1、行动与意识的融合:自发的、自动的行动/反应。换而言之,你是自然而然地做事,头脑根本不用想。(事实上你的大脑运转得比思考得更快——当你玩《俄罗斯方块》达到“ 心流”状态时,如果突然想到要保持这种最佳状态,就这么稍稍走神,砖块似乎落得更快了,结果你输了。我就是这样。)

2、全神贯注于当即任务:完全集中注意力,没有半点分心。你不会考虑其他任何任务;你想的是当下,只有当下。

3、达到忘我的境界。当你处于“心流”状态时,你不再是单独的你,而是与周围的一切融为一体。(这里有点禅意)

4、对时间的曲解。奇怪的是,这点有两层意思。有些时候,比如我说的《俄罗斯方块》的例子,时间好像变慢了,事物看似在慢速运动。(其实是你的大脑在高速运转,而万物的 速度并没有变化,你是以自己作为参照物看待周围的一切)也有些时候,时间好像过得更快了。比如你本来打算只玩五分钟,可是六个小时后,你才醒悟过来:一整晚都耗在游戏 上了。

5、活动的体验本身就是目标:为了活动体验的本身而活动,与任何外在的奖励无关。另外,你不会想到更长远的目标,你关注的就是“此时此地”。

我发现比较搞笑的地方,当小孩子不好好读书,而是沉溺于玩游戏时,其父母会抱怨他们“走神”。事实上,玩游戏的小孩子就处于“心流”状态,精神可谓达到高度集中。

游戏中的“心流”状态

简而言之,我们知道,能让人处于“心流”状态的活动必须是有挑战性的。如果任务太简单了,大脑就不会再浪费额外的精力了,因为结果已经有保障了。如果任务太难了,大脑 也没必要再努力了,因为失败是尽早的事。这里的目标必须是努力之后就能达到的。你可以参考下面这幅图:

flow(from postgygaxian.wordpress.com)

如果你的技能水平高,但任务太简单,你就会感到厌烦;如果你的技能水平低,任务却太难,你就会受挫;但如果活动的挑战水平与你当前的技能水平相当,那么你就能达到“心 流”状态。

这对游戏来说很有意义,因为这是很多游戏的乐趣来源。

注意,所谓的“心流”状态与“乐趣”不是近义词,尽管二者存在联系。你没有玩游戏时(甚至在做并不有趣的事)也可能处于“心流”状态。比如,一个办公人员填写表格时也 可能陷入“心流”状态,所以填起表来非常快,但他们可能并没有在学习什么,这个过程也并不有趣,只是沉思罢了。

一点小问题

当你面对一个颇有挑战性的任务时,你会越做越好。之所以有趣是因为你正在学习,记得吧?所以,大多数人得从低技能水平开始进行某项活动(如游戏),如果游戏一开始给予 的任务比较简单,那很好。但如果玩家学会了一定的技能以后呢?如果游戏还是只给简单的任务,那么游戏就无聊了。《Tic-Tac-Toe》游戏就是这样让孩子慢慢失去兴趣的。

顺便一提,我们现在可以回答之前的问题了:什么儿童游戏中缺乏有意义的决策却仍然被视作有乐趣呢?答案是,儿童仍然在从游戏中学到有价值的技能:怎么掷骰子,怎么移动 面板上的标记物,怎么转向,怎么阅读/遵守规则,怎么决定输赢等等。这些技能不是生来就会的,而必须通过重复的游戏来教授和学习。当儿童掌握了这些技能,这款没有什么决 策性的游戏也就失去其乐趣。

理想地来说,作为游戏设计师,你当然是希望你的游戏比《Tic-Tac-Toe》的寿命更长。那么该怎么做呢?以下是解决方案列举:

*随着游戏进程增加难度(我们有时也称之为游戏的“节奏”)。随着玩家的进步,玩家慢慢地进入游戏中更困难的关卡或区域。这在关卡类游戏中普遍存在。

*难度级数或障碍。比较有经验的玩家可以选择更困难的挑战。

*动态难度调整(简称DDA)。这是一种消极反馈环路,即游戏根据玩家的表现调整游戏自身的难度。

*玩家作对手。这当然可以让游戏更好玩,但如果你的对手也在进步,那么游戏仍然保持相同的挑战性(如果游戏的深度够的话)。(如果玩家之间的水平相差悬殊,这个方法就无 效了。我喜欢跟我老婆一起玩游戏,一开始我们的旗鼓相当,但过了阵子,因为其中一方玩得时间更多,技术比另一方更好了,两人之间终于打不起来了。)

*玩家自创挑战。如玩家利用自己的关卡编辑工具制作新关卡。

*理解的多层次(许多策略游戏追求“一时学,一生用”的东西)。你可以几分钟就学会象棋,因为只有六种不同的棋子……但一旦你撑握了,你就开始知道不同的情况用什么棋子 最有效最管用;然后你开始看到棋子、时机和区域控制之间的联系;再然后你可以研究著名的棋阵……

Jenova Chen的《flow》认为应当允许玩家在游戏中根据自己的行动改变难度级数。你厌烦了?那就上调一点难度吧,这样动作就更快了。你受不了了?那就调回刚才的难度吧(如 果有必要,游戏会自动把你踢回更简单的难度级数)。

你可以注意到,当我们看到评论说某游戏具有“重玩性”或“可以玩上好几个小时”,其实是说该游戏特别擅长通过调整自身的难度来适应我们不断进步的表现,从而把不断地我 们留在“心流”状态。

为什么玩游戏?

你可能会疑惑,如果“心流”状态这么令人愉悦,并且就是复杂而神秘的“乐趣”来源,那么为什么我们设计的是游戏而不是其他媒体?为什么不设计一种能触发“心流”状态的 任务,让成千上万的人去为发现治疗癌症的验方而努力工作,而不是沉迷于《魔兽》?为什么不设计一种能触发“心流”状态的大学课堂,那样学生就可以坚持每周学习50小时, 而不是好几周都难得看书几分钟。

游戏天生就擅长把玩家引入“心流”状态,所以设计一款有趣的游戏显然比设计一门课程来得容易。正如Koster在《A Theory of Fun》中所指出的,大脑是一种特征匹配机器,当 我们的大脑处于“心流”状态时,就是在寻找和理解当前出现的特征。我认为游戏在这方面做得相当棒,因为你有三个层面上的特征:审美、动态识别和最终的机制精通。因为所 有游戏都具备这三个层次的特征,所以游戏的乐趣是大多数其他活动的三倍。

“寓教于乐”游戏

你可能会想,如果游戏那么擅长教授,学习也那么愉悦,那么“寓教于乐”游戏不是乐疯了?事实上,“寓教于乐”是个我们非常不情愿提起的词,因为但凡标榜自己是“学中玩 ,玩中学!”的游戏,实际上二者皆失。那到底是为什么呢?

许多“寓教于乐”游戏是这么运作的:你进入游戏,一开始还有点玩头。接着游戏停下不动了,而是跟你灌输一些令人作呕的大道理。听完说教的奖励就是得以继续玩游戏。游戏 玩法被设置成了学习实质上非常不好玩的任务的奖励。

我认为这种游戏设计的思路一开始就是错误的,所谓“上梁不正下梁歪”,按这种思路做出来的游戏必然没有什么价值。这种思路错就错在把“学习”和“乐趣”分离开了,我们 知道,此二者不是单独的概念,而是统一的整体(或至少存在非常紧密的联系)。学习无乐趣,玩乐不教育的假想直接损害了整个游戏,也顺带强化了这个极其有害的概念,即教 育即受罪,乐趣无处寻。

如果我们可以停止告诉孩子们“上学不是让你玩的”,那就太好了。如果我不用一开始就劝服学生相信他们在课堂上应该由衷地好好表现,那肯定会让我们当老师的日子好过得多 。

那么,如果你想设计一款针对教学的游戏,怎么办?这个话题本身就值得专门开一堂课来讨论了。我的回答简要地说就是,首先将学习技能本身固有的乐趣分离出来,然后将其作 为游戏的核心机制。通过综合学习和游戏玩法(而不是将二者作为孤立的概念或活动),你就离所谓的“玩中学,学中玩”的游戏近了一大步了。

提醒老师们

如果到目前为止你对上文没有异议,那么你也许看到了教学与玩乐之间的并行可能。如果学习本身是有趣的,那么你要怎么把乐趣从学科中引出来?

学生做的决策有多少是有趣的?我曾看过一个数据表明,大学生平均十周才在课堂上举手一次——也就是说,每年只有三次有意义的决策!你能做得更好一点吗?考虑一下,布置 一个作业(加入交易的成分,如简单但无聊的作业或困难但有趣的作业)。在课堂上问一些跟学生自身有关的问题,进行课堂讨论或辨论。

是不是有很多学生因为你的课难度太高或太低而受不了?游戏也存在这个问题。游戏对此的解决方式是加入多重难度级数;对付教学的话,可以考虑采用一种分级系统,这种系统 对学习比较差的学生而言,只要能学会基础知识,那就应该能够通过,而学习优秀的学生就可以做更有趣的额外作业。把课堂内容分层次,第一层是非常基础的、每个人都会的“ 傻瓜层”,然后增加确实重要的主要细节,最后给出只有某些学生才可能理解的内容,但那些内容的有趣程度必须至少能让学生有动机学习一点儿。

最有趣的游戏以玩家为中心,关注的首先是为玩家提供高品质的游戏体验。你可以感觉得出来,设计师在一款游戏的哪里制作出了他们想玩的地方,因为它卖了整整五份给设计师 、设计师最好的朋友和设计师的老妈。你可以感觉得到在游戏的什么地方,设计师从那儿开始游戏的内容而不是游戏玩法:这些是有深度、包含剧情和内容层次的游戏,但没有人 看得出,因为游戏玩法太无聊,玩家才玩了五分钟就不想玩了。如果你先考虑学生的经验,再开始制定课程计划,而不是根据你觉得有趣的方式(学生的想法可能跟你不太一样) 来设计课堂或以目录(可能直到你上完课都没提到)为基础,那么你的课堂会是怎么样的呢?

结语

什么是游戏?决策是核心。如果严格地分析游戏(你自己的或别人的),请注意玩家在做什么决策、有多少有意义的决策以及为什么。你理解得越多,你就会越有经验。

游戏并非天生就擅长向玩家教授技能。(无论这些技能有用还是没用。)学习一项新技术——通过完成那些逼使你努力然后提高技能水平的挑战。技能水平是让玩家进入“心流” 状态的先决条件之一。当大脑处于“心流”状态时,人的愉悦程度最高。游戏中感到“有趣”的情绪大多来自这种状态。

好啦,我们的谜题解答完毕!你现在知道了“乐趣”来自哪里,以及如何制造“乐趣”。但这还只是开头,日后我们还将继续探索“乐趣”的本质。

在开课之前,我想让大家先了解以下文献内容:

*Noah Falstein作著的《Natural Funativity》。我们已经就何为乐趣而进行了大量讨论,通过MDA Framework我们了解了多种趣味形式。Noah的理论可以解答为何有些东西一开始 就具有趣味性,有些东西则不然。

*Richard Bartle作著的《Clubs, Diamonds, Hearts, Spades: Players Who Suit MUDs》。如果你还不知道MUD为何物,我简单解释一下MUD就是今天MMO游戏的前身。这里的MUD也 可以替换为《魔兽世界》这类游戏。

*重温MDA Framework内容,尤其是其中涉及的9种趣味元素。

趣味形式

你可能还记得MDA Framework的作者所列举的8种趣味类型:

*感觉。游戏可以直接与感觉挂钩。例如电子游戏中起“点缀作用”的音频和视频,《卡塔岛》中的木制路面和房屋的触觉,或者体育项目中的物理运动,《热舞革命》或者其他任 天堂Wii游戏。

*幻想。游戏可以提供一个模拟现实(也有些人将这种现象称为“逃避现实”),但远比现实生活更有趣的世界。

*叙事。我们之前就曾提到,游戏可能涉及故事元素,而这些故事的创造者可能是设计师,也可能是参与游戏的玩家。

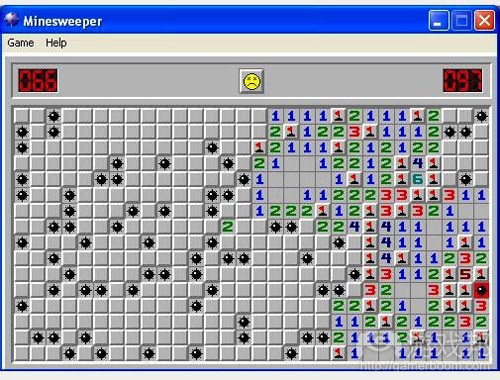

*挑战。有些游戏的趣味性(游戏邦注:尤其是复古街机游戏、专业体育运动,以及象棋和围棋等极具挑战性的桌游)主要来自竞争的刺激性。即使是《扫雷》或登山等单人游戏的 趣味性也主要源于激烈的竞争。

扫雷(from chipchick.com)

*友谊。许多游戏都有明显的社交元素。我想这一点正是《大富翁》等美国桌游戏尽管缺乏有趣决策,游戏机制也无甚趣味,却每年都能实现高销量的原因所在。让玩家与家人共享

社交乐趣,才是这些游戏魅力的所在。

探索。这个特点在桌游中甚为罕见,但在《Tikal》和《Entdecker》等探索类游戏中却可发现这个元素。它在冒险和角色扮演游戏中较为普遍,其中典型代表当属《塞尔达》和《 银河战士》系列。

表现。我认为MDA作者认为这个元素是指玩家通过玩游戏表现自我。例如,字谜或扑克这类游戏偏重于表现你在游戏中的举动;《龙与地下城》则通过游戏角色反映玩家的个人特点 ;《模拟人生》、《侠盗猎车手》、《上古卷轴4:湮灭》、《神鬼寓言》等电子游戏也很重视为玩家提供自定义工具,让他们创造个性化的游戏体验。

服从。游戏是一项持续进行的爱好,而非孤立的活动。这方面的例子包括亚对策概念、《万智牌游戏》中的竞赛场景,还有《魔兽世界》中的公会成员定期会面,以及桌游或角色 扮演群体的每周定期的模仿秀等。

但这并非仅一择其一而行的命题,游戏可以包括多种不同的趣味。

为何不制作一种含有8种趣味元素的游戏?这样不正好迎合所有人的喜好了吗?但事实并非如此。游戏存在8种趣味元素并不意味着所有人都能从这些元素中找到乐子。所以我们常 看到不同游戏结合了不同种类的趣味性,而不同玩家对不同趣味结合体的喜好也不尽相同。我认识的半数人认为象棋很好玩,但另外半数人却不以为然,所以说“趣味”的美感并 非来自游戏本身,而是游戏与玩家的结合。

那么游戏就只有以上这8种趣味元素了吗?不,即使是MDA作者也承认这份趣味列表并不完善。还有其他业内人士也列出了自己的趣味定义,其中包括Nicole Lazzaro的4种关键趣味 元素,Pierre-Alexandre Garneau的14种趣味形式。即使是MDA论文提出的这8种趣味元素也仍然存在争议。例如,把“幻想”和“叙事”拆开真的合理吗,或者说这两者代表不同 的趣味理念?“服从”真的算是一种趣味吗,或者说只有在一种游戏真有强大吸引力从而上升成为玩家的“爱好”时才会发生这种情况?——它究竟算是一种起因还是影响?什么 才能算或者不算“表现”?

“乐趣即学习,学习是乐趣”这种理念究竟从何而来?

进化论

evolution(from forums.nba)

《Natural Funativity》作者Noah Falstein的观点是,趣味性的由来可以追溯到史前时代,当时的原始人只能靠狩猎和采集为生,为了生存和繁殖他们不得不学习许多技能。人们 发现学习某些技能很有趣,就会多实践这种技能,从而更好地生存、繁殖,将自己的基因遗传给下一代。随着时间发展,那些可以让我们生存下来的技能就成了今天“有趣”的东 西。虽然并非所有原始时代的狩猎采集技能现在仍能派上用场,但是要知道,我们的本性并不是那么容易因科技的发展而消失殆尽。

一句话,只要是对原始人有用的东西,你都会发现它很有趣。

Falstein提出了三种趣味性概念:“体能趣味性”(游戏邦注:例如让人们战胜或躲过危险的身体技能),“精神趣味性”(人类用大脑解决问题的能力,例如发明轮子和利用火 源),以及“社交趣味性”(为繁殖下一代以及彼此共存的群居生活所带来的好处)。

当我看到这种观点时,脑中立即闪过《魔兽世界》的影子,这款游戏是不是也存在体能趣味性(战斗),精神趣味性(提升装备和技能),以及社交趣味性(随着《Night Elves》 的背景音乐起舞)?

但我们可以将这种进化论理念运用于任何“趣味形式”,首先来看看MDA在这种情景下的8种趣味性:

*感觉包括身体活动(有利于塑造形体),看到和听到有趣的东西(有利于发现机遇或危险)。

*幻想会让我们脑中的“假设性”场景更为丰满和充实,让我们因此想出更多新主意。

*叙事有助于我们将重要的信息和经验传递给所在群体中的其他成员,增加所有人生存下来的机会。

*挑战是一种相对安全,可让不同人显示自己威力强于他人的便捷途径——如果要建立威信,“我可以把这枚石子扔得比你更远”可能比“让我们一决死战”更管用。

*友谊增加了人们找到新食物来源的可能性(如果我们孤身一人对付巨兽,很快就会毙命,但团结起来就可以把野兽放倒)。另外,离群索居也不利于人类将自己的基因遗传给下一 代。

*探索就是我们探查自己周围环境的本能。我们了解的区域越广,就越可能找到食物来源和栖身之处。

*表现则深深根植于我们通过语言交流的本能。语言和沟通从总体上来说都非常有用。

*服从并非我很了解的概念。但我想它应该更像是趣味性的影响而不是起因。

探索新的趣味形式

我们也可以进行逆向思考,不要再试图从我们的脑子开始找起因,对某些有趣的东西追根溯源,而是独立分析人类祖先的一些求生技能,然后从中找到趣味元素。例如以下几种游 戏中常见的活动:

*收集。这一点起源于人类祖先的“采集”技能,所以你也会发现它很有趣。在我孩提时代,电子游戏还不像现在这么普遍,那时大家最流行集邮。在许多桌游戏中,玩家的任务包 括收集资源或代币。集换式卡牌游戏玩家则搜集卡片。在电子游戏时代,我们的收集癖好始于马里奥搜集钱币。

*空间推理。原始人得弄清楚空间关系才能创建有用的工具(假如你想用一根大木棒制作一个粗糙的梯子或者桥梁,你首先就得计算好木头的长度;如果你想合并两块木板,就得知

道如何让它们彼此相嵌)。从《俄罗斯方块》到《五子棋》,许多游戏都体现了这种空间关系。

*发展。我将此视为一种亚技能,即有利于学习到新技能的技术,这一点对需要掌握大量技能的原始人来说尤其重要。我们总能看到多数游戏都采用了这种机制,例如可让玩家找到 新道具,购买新装备,获得更好的战斗状态或新能力的经验值、等级。

*寻找捷径。找到能够多快好省地解决问题的门道,有利于原始人保存体力,从这一点上看,懒惰倒成为一种美德。讽刺的是,在现代游戏中,这种捷径通常以破坏游戏规则和作弊 等形式出现。

*捣乱。与其他竞争形式一样,征服他人可以建立玩家在群体中的威望(但我们有些人会认为这是令人讨厌且不成熟的表现,但原始人却并不像现代人这么敏感和脆弱)。

也许你还能想出其他各种趣味性,欢迎各位补充。

游戏演变史

玩乐,尤其是玩游戏,让我们锻炼了长大成人的一些技能。虽然我们觉得有趣的技能虽然数百万年的进化才会发生演变,但我们所玩的游戏却是代代不相同,所以你可以通过某个 年代最流行的游戏观察其社会价值观(游戏邦注:例如在几个世纪以前,世界绝大多数人是农民,收割庄稼对人们来说是件大事。但今天的情况不同了,所以我们在现代社会中再 也看不到“收割游戏”的盛行了)。

这为我们设计游戏提供了一个重要的出发点。设计师在动工之前可以先想想自己所在文化圈哪些技能最有用。找到这些技能与原始人求生技能的关联,然后设计一款可实践这些技 能的游戏。许多成功的游戏都极为擅长贯穿学以致用的理念。这类游戏中的活动包括使用玩家需掌握的技能,或者将掌握某项技能作为成功的前提条件。无论是哪种情况,游戏玩 法都会将内在趣味性与学习乐趣融为一体,这样你就有可能做出一款“具有教育意义”同时又不失趣味性的游戏。注意这种游戏与所谓的“寓教于乐”游戏截然不同,后者常要求 人们机械地学习,或者将学习与玩乐孤立起来,已有不少先例证明这种游戏其实很“无趣”。

存在问题

现在我们好像是得到了所有答案。心流状态让人很愉快,我们因自己的本能而自觉训练狩猎采集技能,游戏挖掘这种人类本能,重现了我们称之为“有趣”的东西。

事实果真如此吗?不是。

首先,我们必须解开一个关于“趣味性”的集体困惑。有趣并非唯一让我们快乐的情感,例如设计师常提到的:

*骄傲,这是人们完成一项重大挑战和任务时的胜利感。

*幸灾乐祸,这是一种看到对手失败,自己得手的沾沾自喜,也就是“看自己受伤才觉得不幸,看他人坠崖则是笑话”。

*欣慰,当你的子女、学生或其他与你有半师之缘的人获得成功之时,你会心生一种自豪感(“我为你感到骄傲”),并从中发现自我价值。

*吹牛,你向他人吹嘘自己的子女、学生之时的心情(例如“我孩子从小学开始就是个三好学生”)。

以上这些情感实际上都不能算是“有趣”,它们与心流状态并无直接关系。但它们确实让人获得愉悦感,而且也确实丰富了游戏体验。

正如我们在艺术游戏这一课程中所言,“有趣”并不是游戏的唯一目的。我们阅读《战争与和平》时会觉得它是一本好书,但我们不会称之为有趣。我们也可以说《辛德勒的名单 》和《拯救大兵瑞恩》是好电影,但如果我们说它们很有趣,肯定会让人不解。《麦克白》也不能算是“有趣”的戏剧,看《蒙娜丽莎》也并不有趣,日常新闻也甚少趣味性,但 这些东西却都极具深意。

游戏评论家看《蒙娜丽莎》时可能会说:“视觉效果很棒,但只有一个关卡,互动性太差,没有什么重玩价值。有意思但不好玩,2分(满分为10)”。

但我们其他人可能另有看法。

回顾我之前课程提到的说法——“游戏设计师的职责是让游戏富有趣味性”——现在看来这可能会让大家觉得不自在。趣味性当然是许多游戏的强大元素,但游戏元素并不仅局限 于此。我们游戏设计师的任务远不仅是让游戏更为有趣,而是创造有意义的游戏体验。

有趣是通往有意义游戏体验的一个捷径,但并非唯一途径。

另一个问题

Koster曾在《A Theory of Fun》中指出,玩家本质上都很懒。他们通常只会找那些自己原来就擅长的游戏,所以他们不会去学习新的技能,这就减少了他们所获得的学习乐趣。他 们老是喜欢找漏洞,钻空子和作弊,这些现象都损害了愉快的学习过程。从这一点上看是玩家让游戏趣味性大打折扣,但他们就是要这么做。

公平来说,游戏设计师也难免如此。我们在某些方面的表现比玩家更甚,因为我们都吃透了特定的游戏模式,可以快速将其消化。这就催生出了大量衍生工作。从我个人经验来说 ,我接触的第一个游戏项目是款卡片收集游戏,所以直到现在我还是会习惯性地在自己制作的任何一款游戏中添加卡片、损失/利益决策、稀有性概念等元素。我认识的另一名设计 师则喜欢从RPG角度看问题。另一名同事则喜欢制作模拟题材的游戏。我们多数人都习惯从特定游戏类型出发,制作其他不同的游戏。以我个人经验来看,我们设计游戏时通常会受 到职业生涯中第一款游戏风格的影响。

是否有什么因素让我们偏好特定的游戏类型?如果说是“个人喜好”,那么为何游戏玩家存在如此多重叠特点?

玩家类型

这里就不得不提到Bartle提出的玩家类型理论。与趣味性定义一样,我们也发现许多人也提出了自己主张的玩家类型理论。我们在此介绍Bartle而不提及他人的原因包括:首先, Bartle的论文算是最早获得大众关注及认可的代表作;其次,他的理论有些层面颇有趣味性,值得深入剖析。

让我们先看看Bartle提出的MUD或MMO游戏中的四种玩家类型:

*成就型:这类玩家喜欢获得威力,晋级并“赢得”游戏。

*探索型:他们希望探索世界,会在自己的脑中建立不同区域的心理地图,然后找到自己周围隐藏的事物。

*社交型:他们将游戏作为社交媒介,同其他玩家进行社交互动,游戏只是方便他们与好友相聚的一个理由罢了。

*杀手型:(也可以称为捣乱者)他们将自己的快乐建立在他人的痛苦之上。

Player-Types(from gamification.co)

每种玩家类型的游戏动机是什么?他们为何要选择自己的所作所为?这就要回到不同趣味性的话题。

将Bartle的4种玩家类型与MDA的8种趣味元素进行比较,我们不难发现其中相似之处。成就型玩家喜欢挑战性的乐趣,探索型玩家喜欢探索乐趣,社交型玩家关心友谊之趣,杀手型 玩家虽然并不切合MDA中的任何一种趣味元素,但却能与我所提出的捣乱之趣对号入座。

其他玩家类型理论也显示了同样的关联性:每种“玩家类型”实际上都是一种乐趣,或者数种不同乐趣的合体。玩家和乐趣类型这两者实际上是殊途同归的概念。

这表明你可以罗列出数种不同乐趣,然后根据其结合情况提出新的玩家类型。例如赛车游戏融合了感觉和挑战的乐趣,那我就可以提出“赛车手”这种玩家类型,他们的特点就是 喜欢玩赛车游戏。我还可以推测“极限运动”等其他游戏可能也会吸引这种玩家,因为他们本质上“趣味相投”。

你还可以采用逆向思维,分解出一种新的玩家类型(例如你从游戏测试者中发现的一些“异类”),研究他们喜好的操作习惯,从而发现一种新的趣味形式。

鸡生蛋,蛋生鸡?

如果反复讨论玩家类型和趣味形式,我们可能就会纳闷这究竟是不是一个先有鸡还是先有蛋的问题。究竟是玩家在先,还是乐趣在先?

作为游戏设计师,我们创造了规则(游戏机制),这些规则又创造了游戏动态,从而唤起了玩家的乐趣。我们所创造的东西才是趣味的起源。因此趣味类型才是我们重视的第一要 务。

我们并没有创造玩家类型。游戏设计师创造的规则并没有培养玩家类型,因此以上提到的所有玩家类型只有与趣味相结合时才能体现其意义。

举例来说,《21st Century Game Design》(由Chris Bateman和Richard Boon所著)这本书根据Myers-Briggs人格理论提出了相应的玩家类型。在游戏设计领域中,执行市场调查 结果,并根据目标用户的喜好量体裁衣地设计游戏是一种非常普遍的做法。但这种应用方式存在一个问题。先以Myers-Briggs人格理论反映玩家类型,然后再以玩家类型区分不同 趣味形式。这个过程已经发生了两次概念提纯,这实际上存在很大的出错率。这本书所提出的16种玩家类型并不适用于所有人。

另一个典型的例子就是将玩家简单区分为“休闲”和“硬核”类型。这种分类法可能很适用于游戏的营销推广,但对设计师来说作用有限。这些玩家到底喜欢哪种乐趣?何为“休 闲乐趣”和“硬核乐趣”?这些问题尚无准确答案。不少人认为休闲玩家喜欢体验简洁、容易学习、挑战性不大的游戏。但有些所谓的“休闲游戏”却很困难(例如《美女餐厅》 )、冗长(《Puzzle Quest》)或者复杂(《Virtual Villagers》。我发现与其浪费大量时间定义“休闲玩家”类型,不如去寻找让那些“休闲游戏”大获成功的趣味形式,然后 依此设计游戏。

老师请注意

与上次课程一样,本次主题也与教学课堂颇有相似之处。我提到“玩家类型”和“趣味形式”时,教育工作者可能就会想到“学习方式”这个概念。我所谓的感觉、叙事和表现乐 趣,在他们看来也许可以解读为声音、视觉和动觉学习过程。

老师们也许可以按这种方式授课:

*你在课堂上运用过多少种趣味形式?是否为了让学生全神贯注融入课堂中而动用了多种趣味教学手段?

*感觉上的乐趣很容易实现。不妨把一些有趣的东西带到课堂上让学生们看看,带些可以让他们相互传递的小道具。我认识的一位老师经常在发现学生打嗑睡时让整个班级的同学站 起来做伸展运动。

*叙事乐趣也同样很简单。许多学科都会融入不少故事内容。比起临时杜撰的内容,多数人更易于记住故事。我们天生就有喜欢讲故事和听故事的基因。

*挑战常以问答游戏的形式出现在课堂中。虽然《Jeopardy!》要比一般大学课程更有趣,但学生们并不常制定有趣的决策。但老师们可以采用比这更好的方法,让学生分组进行正 式或非正式的讨论、争辩,使他们获得这种乐趣。

*友谊在学生们分组或进行课堂讨论的时候就会自然形成。

*探索对多数课堂来说并不容易实现,因为人人都只能坐在座位上,无法探索地理情况。实地考察旅行或许是个好方法。如果教室有网络连接,至少可以让学生在线搜索,让他们探 索一个虚拟空间。

*收集这种行为在小学课堂上比较常见,例如奖励学生贴纸或小星星。但高等教育课堂再采用这种方法可能就有风险了(会让学生认为你是把他们当成幼儿园的孩子),但也并非完 全不可行。我认识一位经济学教授,他印刷了一撂印有自己头像的钞票,在课常练习、测试中发放给学生,学生们可以在期末的时候用这种模拟钞票交换真钞或者奖品。

*发展是任何一种课程都存在的固有属性,毕竟每节课都是建立在之前课程的基础之上。假如你利用某节课中大家所学的知识制作一张图表,就会发现这与RTS或MMO游戏中的“科技 树”或“技能树”颇为相似。向学生们展示这种技能图表(然后在他们学到新知识,“解琐”更高级的技能之后向他们再次展示),你就可以为他们创造一种成就感……这种方法 也可以让授课主题更为明晰易了。教育部门的主管也可以效仿此法,以图表形式展示课堂要求和前提条件。

经验总结

从总体上看,我们认为有趣的东西与祖先们为求生而掌握的技能极有渊源。我们在游戏设计过程中可以充分利用这一点,让游戏更加好玩有趣。

有些人认为特定的趣味更有吸引力,毕竟萝卜青菜各有所爱。可以看看你自己最喜欢的游戏(以及你不感兴趣的热门游戏),然后找到自己的“兴趣点”。

记住“乐趣”并非玩家对游戏的唯一情感反映,游戏设计师的目标是无论有趣与否,都要创造引人入胜的游戏体验。在第6个课程内容中,我们曾提到多数艺术游戏并不有趣,但却 极富深意。趣味性是我们的重要追求,但不是唯一目标。

如果你自己去搜索,就会发现许多文献都提出了大量趣味或玩家分类法。但不要将这些内容奉为真理,应该深入分析,并判断其理论的意义所在。从趣味形式来看,你知不知道为 什么我们(或者我们的祖先)会发现各种乐趣?从玩家类型来看,你又如何找到玩家类型与趣味形式的关联性?

相关拓展阅读:篇目5,篇目6,篇目7,篇目8(本文由游戏邦编译,转载请注明来源,或微信咨询zhengjintiao)

Until this point, we have made lots of games and game rules, but at no point have we examined what makes a good rule from a bad one. Nor have we really examined the different kinds of rules that form a game designer’s palette. Nor have we talked about the relationship between the game rules and the player experience. These are the things we examine today.

Course Announcements

No major announcements today, but for your curiosity I did compile a list of tweets for the last challenge (add or change a rule to Battleship to make it more interesting):

* “Reveal” was a common theme (such as, instead of firing a shot, give the number of Hits in a 3×3 square – thus turning the game from “what number am I thinking of” into “two-player competitive Minesweeper”)

* Skip a few turns for a larger shot (for example, skip 5 turns to hit everything in an entire 3×3 area). The original suggestion was an even number (skip 9 turns to nuke a 3×3 square) but note that there isn’t much of a functional difference between this and just taking one shot at a time.

* Like Go, if you enclose an area with a series of shots, all squares in the enclosed area are immediately hit as well (this adds an element of risk-taking and short-term versus long-term tradeoffs to the game – do you try to block off a large area that takes many turns but has an efficient turn-to-squares-hit ratio, or do you concentrate on smaller areas that give you more immediate information but at the cost of taking longer in aggregate?)

* When you miss but are in a square adjacent to an enemy ship, the opponent must declare it as a “near miss” (without telling you what direction the ship is in), which doesn’t exactly get around the guessing-game aspect of the original but should at least speed play by giving added information. Alternatively, with any miss, the opponent must give the distance in squares to the nearest ship (without specifying direction), which would allow for some deductive reasoning.

* Skip (7-X) turns to rebuild a destroyed ship of size X. If the area in which you are building is hit in the meantime, the rebuild is canceled. (The original suggestion was skip X turns to rebuild a ship of size X, but smaller ships are actually more dangerous since they are harder to locate, so I would suggest an inverse relationship between size and cost.)

* Each time you sink an enemy ship, you can rebuild a ship of yours of the same size that was already sunk (this gives some back-and-forth, and suggests alternate strategies of scattering your early shots to give your opponent less room to rebuild)

* Once per game, your Battleship (the size-4 ship) can hit a 5-square cross (+) shaped area in a single turn; using this also forces you to place a Hit on your own Battleship (note that this would also give away your Battleship’s location, so it seems more like a retaliatory move when your Battleship is almost sunk anyway)

We will revisit some of these when we talk about the kinds of decisions that are made in a game, next Monday.

Readings

This week I’m trying something new and putting one of the readings up front, because I want you to look at this first, before reading the rest of this post.

* MDA Framework by LeBlanc, Hunicke and Zabek. This is one of the few academic papers that achieved wide exposure within the game industry (it probably helps that the authors are experienced game designers). There are two parts of this paper that made it really influential. The first is the Mechanics/Dynamics/Aesthetics (MDA) conceptualization, which offers a way to think about the relationship of rules to player experience, and also the relationship between player and designer. The second part to pay attention to is the “8 kinds of fun” which we will return to a bit later in the course

(Thursday of next week).

Now, About That MDA Framework Thing…

LeBlanc et al. define a game in terms of its Mechanics, Dynamics, and Aesthetics:

* Mechanics are a synonym for the “rules” of the game. These are the constraints under which the game operates. How is the game set up? What actions can players take, and what effects do those actions have on the game state? When does the game end, and how is a resolution determined? These are defined by the mechanics.

* Dynamics describe the play of the game when the rules are set in motion. What strategies emerge from the rules? How do players interact with one another?

* Aesthetics (in the MDA sense) do not refer to the visual elements of the game, but rather the player experience of the game: the effect that the dynamics have on the players themselves. Is the game “fun”? Is play frustrating, or boring, or interesting? Is the play emotionally or intellectually engaging?

Before the MDA Framework was written, the terms “mechanics” and “dynamics” were already in common use among designers. The term “aesthetics” in this sense had not, but has gained more use in recent years.

The Process of Design

With the definitions out of the way, why is this important? This is one of the key points of the MDA paper. The game designer only creates the Mechanics directly. The Dynamics emerge from the Mechanics, and the Aesthetics arise out of the Dynamics. The game designer may want to design the play experience, or at least that may be the ultimate goal the designer has in mind… but as designers, we are stuck building the rules of the game and hoping that the desired experience emerges from our rules.

This is why game design is sometimes referred to as a second-order design problem: because we do not define the solution, we define something that creates something else that creates the solution. This is why game design is hard. Or at least, it is one reason. Design is not just a matter of coming up with a “Great Idea” for a game; it is about coming up with a set of rules that will implement that idea, when two-thirds of the final product (the Dynamics and Aesthetics) are not under our direct control.

The Process of Play

Designers start with the Mechanics and follow them as they grow outward into the Aesthetics. You can think of a game as a sphere, with the Mechanics at the core, the Dynamics surrounding them, and the Aesthetics on the surface, each layer growing out of the one inside it. One thing the authors of MDA point out is that this is not how games are experienced from the player’s point of view.

A player sees the surface first – the Aesthetics. They may be aware of the Mechanics and Dynamics, but the thing that really makes an immediate impression and that is most easily understood is the Aesthetics. This is why, even with absolutely no knowledge or training in game design, anyone can play a game and tell you whether or not they are having a good time. They may not be able to articulate why they are having a good time or what makes the game “good” or “

bad”… but anyone can tell you right away how a game makes them feel.

If a player spends enough time with a game, they may learn to appreciate the Dynamics of the game and now their experience arises from them. They may realize that they do or don’t like a game because of the specific kinds of interactions they are having with the game and/or the other players. And if a player spends even more time with that game, they may eventually have a strong enough grasp of the Mechanics to see how the Dynamics are emerging from them.

If a game is a sphere that is designed from the inside out, it is played from the outside in. And this, I think, is one of the key points of MDA. The designer creates the Mechanics and everything flows outward from that. The player experiences the Aesthetics and then their experience flows inward. As designers, we must be aware of both of these ways of interacting with a game. Otherwise, we are liable to create games that are fun for designers but not players.

One Example of MDA in action

I mentioned the concept of “spawn camping” earlier in this course, as an example of how players with different implicit rule sets can throw around accusations of “cheating” for something that is technically allowed by the rules of the game. Let us analyze this in the context of MDA.

In a First-Person Shooter video game, a common mechanic is for players to have “spawn points” – dedicated places on the map where they re-appear after getting killed. Spawn points are a mechanic. This leads to the dynamic where a player may sit next to a spawn point and immediately kill anyone as soon as they respawn. And lastly, the aesthetics would likely be frustration at the prospect of coming back into play only to be killed again immediately.

Suppose you are designing a new FPS and you notice this frustration aesthetic in your game, and you want to fix this so that the game is not as frustrating. You cannot simply change the aesthetics of the game to “make it more fun” – this may be your goal, but it is not something under your direct control. You cannot even change the dynamics of spawn camping directly; you cannot tell the players how to interact with your game, except through the mechanics. So instead, you must change the mechanics of the game – maybe you try making players respawn in random locations rather than designated areas – and then you hope that the desired aesthetics emerge from your mechanics change.

How do you know if your change worked? Playtest, of course!

How do you know what change to make, if the effects of mechanics changes are so unpredictable? We will get into some basic tips and tricks near the end of this course. For now, the most obvious way is designer intuition. The more you practice, the more you design games, the more you make rules changes and thenplaytest and see the effects of your changes, the better you will get at making the right changes when you notice problems… and occasionally, even creating

the right mechanics in the first place. There are few substitutes for experience… which, incidentally, is why so much of this course involves getting you off your butt and making games .

“If the computer or the game designer is having more fun than the player, you have made a terrible mistake.”

This seems as good a time as any to quote game designer Sid Meier. His warning is clearly directed at video game designers, but applies just as easily to non-digital projects. It is a reminder that we design the Mechanics of the game, and designing the Mechanics is fun for us. But it is not the Mechanics that are fun for our players. A common design mistake is to create rules that are fun to create, but that do not necessarily translate into fun gameplay. Always

remember that you are creating games for the players and not yourself.

Mechanics, Dynamics and Complexity

Generally, adding additional mechanics, new systems, additional game objects, and new ways for objects to interact with one another (or for players to interact with the game) will lead to a greater complexity in the dynamics of the game. For example, compare Chess and Checkers. Chess has six kinds of pieces (instead of two) and a greater number of actions that each piece can take, so it ends up having more strategic depth.

Is more complexity good, or bad? It depends. Tetris is a very simple but still very successful game. Advanced Squad Leader is an incredibly complex game, but still can be considered successful for what it is. Some games are so simple that they are not fun beyond a certain age, like Tic-Tac-Toe. Other games are too complex for their own good, and would be better if their systems were a bit more simplified and streamlined (I happen to think this about the board game

Agricola; I’m sure you can provide examples from your own experience).

Do more complex mechanics always lead to more complex dynamics? No – there are some cases where very simple mechanics create extreme complexity (as is the case with Chess). And there are other cases where the mechanics are extremely complicated, but the dynamics are simple (imagine a modified version of the children’s card game War that did not just involve comparison of numbers, but lookups on complex “combat resolution” charts). The best way to gauge

complexity, as you may have guessed, is to play the game.

Feedback Loops

One kind of dynamic that is often seen in games and deserves special attention is known as the feedback loop. There are two types, positive feedback loops and negative feedback loops. These terms are borrowed from other fields such as control systems and biology, and they mean the same thing in games that they mean elsewhere.

A positive feedback loop can be thought of as a reinforcing relationship. Something happens that causes the same thing to happen again, which causes it to happen yet again, getting stronger in each iteration – like a snowball that starts out small at the top of the hill and gets larger and faster as it rolls and collects more snow.

As an example, there is a relatively obscure shooting game for the NES called The Guardian Legend. Once you beat the game, you got access to a special extra gameplay mode. In this mode, you got rewarded with power-ups at the end of each level based on your score: the higher your score, the more power-ups you got for the next level. This is a positive feedback loop: if you get a high score, it gives you more power-ups, which make it easier to get an even higher score

in the next level, which gives you even more power-ups, and so on.

Note that in this case, the reverse is also true. Suppose you get a low score. Then you get fewer power-ups at the end of that level, which makes it harder for you to do well on the next level, which means you will probably get an even lower score, and so on until you are so far behind that it is nearly impossible for you to proceed at all.

The thing that is often confusing to people is that both of these scenarios are positive feedback loops. This seems counterintuitive; the second example seems very “negative,” as the player is doing poorly and getting fewer rewards. It is “positive” in the sense that the effects get stronger in magnitude on each iteration.

There are three properties of positive feedback loops that game designers should be aware of:

1.They tend to destabilize the game, as one player gets further and further ahead (or behind).

2.They cause the game to end faster.

3.The put emphasis on the early game, since the effects of early-game decisions are magnified over time.

Feedback loops usually have two steps (as in my The Guardian Legend example) but they can have more. For example, some Real-Time Strategy games have a positive feedback loop with four steps: players explore the map, which gives them access to more resources, which let them buy better technology, which let them build better units, which let them explore more effectively (which gives them access to more resources… and the cycle repeats). As such, detecting a

positive feedback loop is not always easy.

Here are some other examples of positive feedback loops that you might be familiar with:

* Most “4X” games, such as the Civilization and Master of Orion series, are usually built around positive feedback loops. As you grow your civilization, it lets you generate resources faster, which let you grow faster. By the time you begin conflict in earnest with your opponents, one player is usually so far ahead that it is not much of a contest, because the core positive feedback loop driving the game means that someone who got ahead of the curve early on is going to be much farther ahead in the late game.

* Board games that feature building up as their primary mechanic, such as Settlers of Catan. In these games, players use resources to improve their resource production, which gets them more resources.

* The physical sport Rugby has a minor positive feedback loop: when a team scores points, they start with the ball again, which makes it slightly more likely that they will score again. The advantage is thus given to the team who just gained an advantage. This is in contrast to most sports, which give the ball to the opposing team after a successful score.

Negative feedback loops are, predictably, the opposite of positive feedback loops in just about every way. A negative feedback loop is a balancing relationship. When something happens in the game (such as one player gaining an advantage over the others), a negative feedback loop makes it harder for that same thing to happen again. If one player gets in the lead, a negative feedback loop makes it easier for the opponents to catch up (and harder for a winning player to extend their lead).

As an example, consider a “Kart-style” racing game like Mario Kart. In racing games, play is more interesting if the player is in the middle of a pack of cars rather than if they are way out in front or lagging way behind on their own (after all, there is more interaction if your opponents are close by). As a result, the de facto standard in that genre of play is to add a negative feedback loop: as the player gets ahead of the pack, the opponents start cheating, finding better power-ups and getting impossible bursts of speed to help them catch up. This makes it more difficult for the player to maintain or extend a lead. This particular feedback loop is sometimes referred to as “rubber-banding” because the cars behave as if they are connected by rubber bands, pulling the leaders and losers back to the center of the pack.

Likewise, the reverse is true. If the player falls behind, they will find better power-ups and the opponents will slow down to allow the player to catch up. This makes it more difficult for a player who is behind to fall further behind. Again, both of these are examples of negative feedback loops; “negative” refers to the fact that a dynamic becomes weaker with iteration, and has nothing to do with whether it has a positive or negative effect on the player’s standing in the game.

Negative feedback loops also have three important properties:

1.They tend to stabilize the game, causing players to tend towards the center of the pack.

2.They cause the game to take longer.

3.They put emphasis on the late game, since early-game decisions are reduced in their impact over time.

Some examples of negative feedback loops:

* Most physical sports like Football and Basketball, where after your team scores, the ball is given to the opposing team and they are then given a chance to score. This makes it less likely that a single team will keep scoring over and over.

* The board game Starfarers of Catan has a negative feedback loop where every player with less than a certain number of victory points gets a free resource at the start of their turn. Early on, this affects all players and speeds up the early game. Later in the game, as some players get ahead and cross the victory point threshold, the players lagging behind continue to get bonus resources. This makes it easier for the trailing players to catch up.

* My grandfather was a decent Chess player, generally better than his children who he taught to play. To make it more of a challenge, he invented a rule: if he won a game, next time they played, his opponent could remove a piece of his from the board at the start of the game (first a pawn, then two pawns, then a knight or bishop, and so on as the child continued to lose). Each time my grandfather won, the next game would be more challenging for him, making it more likely that he would eventually start losing.

Use of Feedback Loops

Are feedback loops good or bad? Should we strive to include them, or are they to be avoided? As with most aspects of game design, it depends on the situation. Sometimes, a designer will deliberately add mechanics that cause a feedback loop. Other times, a feedback loop is discovered during play and the designer must decide what (if anything) to do about it.

Positive feedback loops can be quite useful. They end the game quickly when a player starts to emerge as the winner, without having the end game be a long, drawn-out affair. On the other hand, positive feedback loops can be frustrating for players who are trying to catch up to the leader and start feeling like they no longer have a chance.

Negative feedback loops can also be useful, for example to prvent a dominant early strategy and to keep players feeling like they always have a chance to win. On the other hand, they can also be frustrating, as players who do well early on can feel like they are being punished for succeeding, while also feeling like the players who lag behind are seemingly rewarded for doing poorly.

What makes a particular feedback loop “good” or “bad” from a player perspective? This is debatable, but I think it is largely a matter of player perception of fairness. If it feels like the game is artificially intervening to help a player win when they don’t deserve it, it can be perceived negatively by players. How do you know how players will perceive the game? Playtest, of course.

Eliminating Feedback Loops

Suppose you identify a feedback loop in your game and you want to remove it. How do you do this? There are two ways.

The first is to shut off the feedback loop itself. All feedback loops (positive and negative) have three components:

* A “sensor” that monitors the game state;

* A “comparator” that decides whether to take action based on the value monitored by the sensor;

* An “activator” that modifies the game state when the comparator decides to do so.

For example, in the earlier kart-racing negative feedback loop example, the “sensor” is how far ahead or behind the player is, relative to the rest of the pack; the “comparator” checks to see if the player is farther ahead or behind than a certain threshold value; and the “activator” causes the opposing cars to either speed up or slow down accordingly, if the player is too far ahead or behind. All of these may form a single mechanic (“If the player is more than 300 meters ahead of all opponents, multiply everyone else’s speed by 150%”). In other cases there may be three or more separate mechanics that cause the feedback loop, and changing any one of them will modify the nature of the loop.

By being aware of the mechanics causing a feedback loop, you can disrupt the effects by either removing the sensor, changing or removing the comparator, or modifying or removing the effect of the activator. Going back to our The Guardian Legend example (more points = more power-ups for the next level), you could deactivate the positive feedback loop by either modifying the sensor (measure something other than score… something that does not increase in proportion to how powered-up the player is), or changing the comparator (by changing the scores required so that later power-ups cost more and more, you can guarantee that even the best players will fall behind the curve eventually, leading to a more difficult end game), or changing the activator (maybe the player gets power- ups through a different method entirely, such as getting a specific set of power-ups at the end of each level, or finding them in the middle of levels).

If you do not want to remove the feedback loop from the game but you do want to reduce its effects, an alternative is to add another feedback loop of the opposing type. Again returning to the kart-racing example, if you wanted to keep the “rubber-banding” negative feedback loop, you could add a positive feedback loop to counteract it. For example, if the opposing cars get speed boosts when the player is ahead, perhaps the player can go faster as well, leading to a case where being in the lead makes the entire race go faster (but not giving an advantage or disadvantage to anyone). Or maybe the player in the lead can find better power-ups to compensate for the opponents’ new speed advantage.

Emergence

Another dynamic that game designers should be aware of is called emergent gameplay (or emergent complexity, or simply emergence). I’ve found this is a difficult thing to describe in my classroom courses, so I would welcome other perspectives on how to teach it. Generally, emergence describes a game with simple mechanics but complex dynamics. “Emergent complexity” can be used to describe any system of this nature, even things that are not games.

Some examples of emergence from the world outside of games:

* In nature, insect colonies (such as ants and bees) show behavior that is so complex, it appears to be intelligent enough that we call it a “hive mind” (much to the exploitation of many sci-fi authors). In reality, each individual insect is following its own very simple set of rules, and it is only in aggregate that the colony displays complex behaviors.

* Conway’s Game of Life, though not actually a “game” by most of the definitions in this course, is a simple set of sequential rules for simulating cellular life on a square grid. Each cell is either “alive” or “dead” on the current turn. To progress to the next turn, all living cells that are adjacent to either zero or one other living cells are killed (from isolation), and living cells adjacent to four or more other living cells are also killed (from overcrowding); all dead cells adjacent to exactly three living cells are “born” and changed to living cells on the next turn; and any cell adjacent

to exactly two living cells stays exactly as it is. Those are the only rules. You start with an initial setup of your choice, and then modify the board to see what happens. And yet, you can get incredibly complex behaviors: structures can move, mutate, spawn new structures, and any number of other things.

* Boid’s Algorithm, a way to simulate crowd and flocking behavior that is used in some CG-based movies as well as games. There are only three simple rules that individuals in a flock must each follow. First, if there are a lot of your companions on one side of you and few on the other, it means you’re probably at the edge of the flock; move towards your companions. Second, if you are close to your companions, give them room so you don’t crowd them. Third, adjust

your speed and direction to be the average of your nearby companions. From these three rules you can get some pretty complex, detailed and realistic crowd behavior.

Here are some examples of emergent gameplay:

* In fighting games like the Street Fighter or Tekken series, “combos” arise from the collision of several simple rules: connecting with certain attacks momentarily stuns the opponent so that they cannot respond, and other attacks can be executed quickly enough to connect before the opponent recovers. Designers may or may not intentionally put combos in their games (the earliest examples were not intended, and indeed were not discovered until the games had been out for awhile), but it is the mechanics of stunning and attack speed that create complex series of moves that are unblockable after the first move in the series connects.

* In the sport of Basketball, the concept of “dribbling” was not explicitly part of the rules. As originally written, the designer had intended the game to be similar to how Ultimate Frisbee is played: the player with the ball is not allowed to move, and must either throw the ball towards the basket (in an attempt to score), or “pass” the ball to a teammate (either through the air, or by bouncing it on the ground). There was simply no rule that prevented a player from passing to himself.

* Book openings in Chess. The rules of this game are pretty simple, with only six different piece types and a handful of special-case moves, but a set of common opening moves has emerged from repeated play.

Why do we care about emergent dynamics? It is often desired for practical reasons, especially in the video game world, because you can get a lot of varied and deep gameplay out of relatively simple mechanics. In video games (and to a lesser extent, board games) it is the mechanics that must be implemented. If you are programming a video game, emergent gameplay gives you a great ratio of hours-of-gameplay to lines-of-code. Because of this apparent cost savings,

“emergence” as a buzzword was all the rage a few years ago, and I still hear it mentioned from time to time.

It’s important to note that emergence is not always planned for, and for that matter it is not always desirable. Here are two examples of emergence, both from the Grand Theft Auto series of games, where unintended emergent gameplay led to questionable results:

* Consider these two rules. First, running over a pedestrian in a vehicle causes them to drop the money they are carrying. Second, hiring a prostitute refills the player’s health, but costs the player money. From these two unrelated rules, we get the emergent strategy that has been affectionately termed the “hooker exploit”: sleep with a prostitute, then run her over to regain the money you spent. This caused a bit of a scandal in the press back in the day, from people who interpreted this dynamic as an intentional design that glorified violence against sex workers. Simply saying “it’s emergent gameplay! ” is not sufficient to explain to a layperson why this was not intentional.

* Perhaps more amusing was the combination of two other rules. First, if the player causes damage to an innocent bystander, the person will (understandably) defend themselves by attacking the player. Second, if a vehicle has taken sufficient damage, it will eventually explode, damaging everything in the vicinity (and of course, nearly killing the driver). These led to the following highly unrealistic scenario: a player, driving a damaged vehicle, crashes near a group

of bystanders. The car explodes. The player crawls from the wreckage, barely alive… until the nearby crowd of “Samaritans” decides that the player damaged them from the explosion, and they descend in a group to finish the player off!

As you can see, emergence is not always a good thing. More to the point, it is not necessarily cheaper to develop a game with emergent properties. Because of the complex nature of the dynamics, emergent games require a lot more playtesting and iteration than games that are more straightforward in their relationships between mechanics and dynamics. A game with emergence may be easier to program, but it is much harder to design; there is no cost savings, but rather a shift in cost from programmers to game designers.

From Emergence to Intentionality

Player intentionality, the concept from Church’s Formal Abstract Design Tools mentioned earlier in this course, is related in some ways to emergence. Generally, you get emergence by having lots of small, simple, interconnected systems. If the player is able to figure out these systems and use them to form complicated chains of events intentionally, that is one way to have a higher degree of player intention.

Another Reading

* Designing to Promote Intentional Play by Clint Hocking. This was a lecture given live at GDC in 2006, but Clint has kindly made his Powerpoint slides and speaker notes publicly available for download from his blog. It covers the concept of player intentionality and its relation to emergence, far better than I can cover here. The link goes to a Zip file that contains a number of files inside it; start with the Powerpoint and the companion Word doc, and the presentation will make it clear when the other things like the videos come into play. I will warn you that, like many video game developers, Clint tends to use a lot of profanity; also, the presentation opens with a joke about Jesus and Moses. It may be best to skip this one if you are around people who are easily offended by such things.

Lessons Learned

The most important takeaway from today is that game design is not a trivial task. It is difficult, mainly because of the nature of MDA. The designer creates rules, which create play, which create the player experience. Every rule created has a doubly-indirect effect on the player, and this is hard to predict and control. This also explains why making one small rules change in a game can have ripple effects that drastically alter how the game is played. And yet, a designer’s task is to create a favorable player experience.

This is why playtesting is so important. It is the most effective way to gauge the effects of rules changes when you are uncertain.

Homeplay

Today we will practice iterating on an existing design, rather than starting from scratch. I want you to see first-hand the effects on a game when you change the mechanics.

Here are the rules for a simplified variant of the dice game called Bluff (also called Liar’s Dice, but known to most people as that weird dice game that they played in the second Pirates of the Caribbean movie):

* Players: 2 or more, best with a small group of 4 to 6.

* Objective: Be the last player with any dice remaining.

* Setup: All players take 5 six-sided dice. It may also help if each player has something to hide their dice with, such as an opaque cup, but players may just shield their dice with their own hands. All players roll their dice, in such a way that each player can see their own dice but no one else’s. Choose aplayer to go first. That player must make a bid:

* Bids: A “bid” is a player’s guess as to how many dice are showing a certain face, among all players. Dice showing the number 1 are “wild” and count as all other numbers. You cannot bid any number of 1s, only 2s through 6s. For example, “three 4s” would mean that between every player’s dice, there are at least three dice showing the number 1 or 4.

* Increasing a bid: To raise a bid, the new bid must be higher than the previous. Increasing the number of dice is always a higher bid, regardless of rank (nine 2s is a higher bid than eight 6s). Increasing the rank is a higher bid if the number of dice is the same or higher (eight 6s is a higher bid than eight 5s, both of which are higher than eight 4s).

* Progression of Play: On a player’s turn, that player may either raise the current bid, or if they think the most recent bid is incorrect, they can challenge the previous bid. If they raise the bid, play passes to the next player in clockwise order. If they challenge, the current round ends; all players reveal their dice, and the result is resolved.

* Resolution of a round: If a bid is challenged but found to be correct (for example, if the bid was “nine 5s” and there are actually eleven 1s and 5s among all players, so there were indeed at least nine of them), the player who challenged the bid loses one of their dice. On subsequent rounds, that player will then have fewer dice to roll. If the bid is challenged correctly (suppose on that bid of “nine 5s” there were actually only eight 1s and 5s among all players), the player who made the incorrect bid loses one of their dice instead. Then, all players re-roll all of their remaining dice, and play continues with a new opening bid, starting with the player who won the previous challenge.

* Game resolution: When a player has lost all of their dice, they are eliminated from the game. When all players (except one) have lost all of their dice, the one player remaining is the winner.

If you don’t have enough dice to play this game, you can use a variant: dealing cards from a deck, for example, or drawing slips of paper numbered 1 through 6 out of a container with many such slips of paper thrown in.

If you don’t have any friends, spend some time finding them. It will make it much easier for you to playtest your projects later in this course if you have people who are willing to play games with you.

At any rate, your first “assignment” here is to play the game. Take particular note of the dynamics and how they emerge from the mechanics. Do you see players bluffing, calling unrealistically high numbers in an effort to convince their opponents that they have more of a certain number than they actually do? Are players hesitant to challenge, knowing that any challenge is a risk and it is therefore safer to not challenge as long as you are not challenged yourself? Do any players calculate the odds, and use that information to influence their bid? Do you notice any feedback loops in the game as play progresses – that is, as a player starts making mistakes and losing dice, are they more or less likely to lose again in future rounds, given that they receive fewer dice and therefore have less information to bid on?

Okay, that last question kind of gave it away – yes, there is a positive feedback loop in this game. The effect is small, and noticeable mostly in an end- game situation where one player has three or more dice and their one or two remaining opponents only have a single die. Still, this gives us an opportunity to fiddle with things as designers.

Your next step is to add, remove, or change one rule in order to remove the effect of the positive feedback loop. Why did you choose the particular change that you did? What do you expect will happen – how will the dynamics change in response to your modified mechanic? Write down your prediction.

Then, play the game again with your rules modification. Did it work? Did it have any other side effects that you didn’t anticipate? How did the dynamics actually change? Be honest, and don’t be afraid if your prediction wasn’t accurate. The whole point of this is so you can see for yourself how hard it is to predict gameplay changes from a simple rules change, without actually playing.

Next, share what you learned with the community. I have created a new page on the course Wiki. On that page, write the following:

1.What was your rules change?

2.How did you expect the dynamics of the game to change?

3.How did they really change?

You don’t need to include much detail; a sentence or two for each of the three points is fine.

Finally, your last assignment (this is mandatory!) is to read at least three other responses. Read the rules change first, and without reading further, ask yourself how you think that rule change would modify gameplay. Then read the other person’s prediction, and see if it matches yours. Lastly, read what actually happened, and see how close you were.

You may leave your name, or you may post anonymously.

Mini-Challenge

Take your favorite physical sport. Identify a positive or negative feedback loop in the game. Most sports have at least one of these. Propose a rule change that would eliminate it. Find a way to express it in less than 135 characters, and post to Twitter with the #GDCU tag. You have until Thursday. One sport per participant, please!

At this point I’d like to take a brief diversion to go into the whole “can games be art?” thing. This may seem like a strange topic to cover in the middle of some heftier design principles. It’s also one of those tired old arguments that have been going on for years now, so why waste our time retreading old ground? I have a few reasons for including this in the syllabus, and you are free to debate the merits and drawbacks of its inclusion in this course.

The first reason for this topic is that for the next few weeks we’ll be talking about the whole concept of “fun” and how to make games more enjoyable. For most practicing game designers, this is their prime directive: Take This Game And Make It Fun. Before we go down that road, I want to make it clear that fun is not the only purpose of game design, and in fact that some games can be critically successful in their design goals even if they are not particularly “fun” in the way that most games are.

Second, as a debate that has been going on for ages, I want those who are new to the party to get a basic grounding in the debate. It’s one of those things that will certainly come up in conversation among designers from time to time, and I want the novices among you to be prepared to enter that discussion. For those of you who are quite familiar with this already, I hope to up the ante so that we can all proceed in these discussions at a higher level of discourse.

Third, so-called “art games” – that is, games that are made primarily for the purpose of artistic expression (as opposed to entertainment) – are reaching a critical mass. There are a lot of very talented people doing very interesting things in this space right now. A lot of art games are very simple and small in scope, made by a single person in a relatively short period of time. A lot of potential avenues are yet to be explored. This makes art games a wonderful opportunity for those who are looking to establish themselves as game designers.

And finally, I know just enough about art history and art criticism to be dangerous. I am therefore driven, to an extent, to talk about an area of personal interest… even though I acknowledge that it will undoubtedly get me into trouble at some point.

Course Announcements

For those paying close attention, I recently changed my Twitter username from @ai864 to @IanSchreiber, after urging from co-author Brenda Brathwaite (@bbrathwaite). The theory is that my actual name will be easier to remember… provided people learn to spell it correctly. Keep in mind, for those of you who tweet about this course regularly.

Mini-Challenge Results

Here are a small selection of the answers to the mini-challenge from last time (identify a physical sport with a feedback loop, and propose a rule change to eliminate it):

?8-ball (pocket billiards): Negative feedback loop is that the more of your own balls you sink, the fewer legal targets you have. Rule change: sunk balls are reset on the table, first to sink any seven of their balls can attempt to sink the 8-ball for the win. Alternate rule change: after failing to sink a ball, opponent automatically gets a point.

?Martial arts, boxing, and similar: Positive feedback loop is that the more you injure your opponent, the less likely they are to retaliate. Rule change:

wait a day between rounds. (Impractical perhaps, although it would probably cut down on serious injury.)

?Soccer, Basketball, and most other team sports: Negative feedback loop where after scoring, the ball is given to the other team. Rule change: after scoring, use a “jump ball” or equivalent to give both teams an equal chance to reclaim the ball.

?Croquet: Positive feedback loop is that you get bonus swings for hitting wickets. Rule change: make the bonus swings optional, keep track of total number of swings throughout the game, lowest number of swings wins.

?Most professional sports: Positive feedback loop is that a team that wins a lot gets more money (from fans, sponsorships, etc.), which lets them buy better players, which makes it more likely they will continue to win. Rule change: not given. (This is actually a real struggle with some professional sports, because it is more exciting to watch a game if you feel like both teams have a chance to win. In the real world, some proposals to fix this include drafts

and salary caps. Sports that don’t do something to prevent this feedback loop tend to lose popularity. I’m looking at you, American Baseball.)

?Cycling, auto racing, and similar: Negative feedback loop is the ability to draft behind the person in front of you, letting you save energy so that you can overtake them later. Rule change: race in a vacuum. (Very funny, wise guy.)

Readings

Due to the positive response from Monday, I’ll continue putting the readings up front. Go do these now: