阐述定义“休闲”与“硬核”体验的准则

作者:Brian Keschinger

电子游戏媒体相对于电影、文学和音乐等其他娱乐形式来说,还是一种极为年轻的媒体。随着这种媒体的成长,与其玩家和游戏相关的两种描述也开始浮现:休闲与硬核。本文主旨是探讨休闲与硬核游戏、玩家的定义由来。

随着游戏的发展,这种媒体开始变得更为复杂,每款游戏都是在前者的惯例上继续成长。由于游戏变得更为复杂,游戏社区也开始划分为两个不同的派别:休闲和硬核。Braxton Soderman将休闲游戏定义为供女性在短时间内体验以打发时间的游戏。而Michael Samyn则认为硬核游戏就是由青少年男孩体验的富有竞争元素的游戏。

这种刻板印象在过去几年中愈演愈烈,在今天的游戏文化中也更为盛行了。发行商使用这一刻板印度作为营销手段,开发者也针对特定的亚文化制作游戏,玩家则不希望被称为另一种有别于自我标榜的游戏群体。但这些刻板印象的定义也存在问题,无论它是来自社区还是学者——休闲和硬核玩家之间的界线是模糊的,这两种游戏的属性也并不完全彼此独立。

其中多数原因在于定义休闲与硬核玩家、游戏时留下了太多灰色地带。这是因为与玩家和游戏相关的定义很松散,并且取决于个人体验。但玩家和游戏的互动却可以产生我认为能够区分硬核或休闲的体验。决定某一体验是休闲还是硬核的要取决于玩家选择如何玩游戏。游戏只是玩家表现的平台,它们无法决定玩家会采取哪类玩法风格。

休闲或硬核“体验”的定义可以抵抗更多压力,因为这些定义比休闲或硬核玩家、游戏体验的定义更为具体。体验的定义准则要取决于两个因素:玩家和游戏。玩家与游戏互动会产生体验,但玩家与游戏在准则中的比重却并不相同。玩家是该准则的主要因素,几乎决定了游戏体验。而游戏在这一准则中仍然很重要,因为它是玩家产生体验的场所。

定义玩家、游戏为休闲或硬核是一个尝试性的过程,因为人们有多种方式来体验特定的游戏。保守的中年妇女可以通过在《Candy Crush》中表现最好而创造也硬核玩法。即便游戏或玩家的休闲或硬核定义很容易崩溃,它们也是研究休闲或硬核体验的一个重要环节。在下一环节中,我将探讨玩家角色,以及游戏检验为何只是提供了一系列体验的工具,并且是玩家表现的场所,解释每个因素如何定义休闲或硬核体验。

玩家

玩家主导体验的定义,他们是决定如何玩游戏的个体。玩家创造许多决策,意识和潜意识,例如在游戏中投入多少时间,以及他们玩游戏的动机是什么。

如果玩家选择在某款游戏中投入数小时,这几乎就是一种硬核体验了。而那些可以边走边玩的游戏,则属于另一种极端。如果玩家是在上下班的公交车上玩手机游戏,那么这就是比投入漫长时间的游戏更为休闲的体验。不同的投入时间还引起了另一个问题:玩家是在玩游戏时投入时间还是打发时间呢?

打发时间vs投入时间是现代游戏时长的一个重要二分法。手机游戏,由于移动设备的发展,几乎成了人人都可以随时接触的设备。Soderman在自己的论文《透过现代视角看电子游戏》中指出:

休闲游戏总体上更倾向于打发时间,允许人们在等待婴儿小憩醒来,等待列车到来,等待同事来开会的过程中体验……上班族经常会在工作之余休息片刻时玩玩休闲游戏,但这些游戏当然也可以在家玩(或者任何玩家可以使用手机的地方)。

如果玩家体验游戏是为了打发时间,那么这就是休闲体验。在硬核体验中,玩家会投入时间探索游戏,互动、观看,甚至是竞争。这并不是说所有边走边玩的游戏都是休闲的,但它显然是这类体验发生的更直接场所。玩家可能会在上下班等车的过程中玩《Candy Crush》,目的是为了获得世界上的最高分。即便《Candy Crush》的多数体验是休闲的,这个特别的例子也可能产生硬核体验。

玩家的意图是除了时间之外的另一个定义玩家的因素。继续刚才的例子,如果玩家打算在《Candy Crush》中获得世界最高分,并为了达到这个目的反复玩同个关卡,那么这就属于硬核体验。但如果碰到好运,玩家只是为了在上班途中打发时间,但却偶然获得了游戏中的世界最高分,那么这就是休闲体验了。无论是《Candy Crush》、《使命召唤》、《星际争霸》还是《料理妈妈》,为了好玩而体验游戏就是硬核体验。在游戏中为获胜而竞争的天性就是硬核体验。如果玩家只是为了社交目的而玩游戏,那么这通常就是休闲体验。Jesper Juul在自己的书籍《A Casual Revolution:Reinventing Video Games and Their players》中描述了相同游戏中的玩家意图可能影响其产生的游戏体验:

《吉他英雄》和《摇滚乐队》因玩家的游戏目标而呈现区别。如果你想以社交活动的方式玩游戏,那你就一次玩一首歌。在这种情况下,游戏只需要少量的时间投入,这更接近于休闲游戏设计原则。如果你玩游戏的目标是精通游戏,你就会反复玩同一首歌,并且会记得完成一首歌需要摁压的按键。这种情况下,这种游戏就接近于传统硬核游戏设计原则。

像《吉他英雄》和《摇滚乐队》这种游戏的社交属性令其更容易成为休闲体验,但玩家体验游戏的意图才是定义该体验的决定因素。这两款游戏都落入了没有目标或拥有可选目标的游戏分类范畴。例如,著名的《侠猎猎车手》系列通常以其庞大、开放世界、长达数小时的叙事,技能要求等元素而呈现更为硬核的体验,但由于游戏目标是可选择的,也很容易落入休闲游戏体验范畴。Juul进一步解释道:

缺乏目标或者只有可选择目标的游戏更富有弹性:它们可包容更多玩法风格和玩家类型,实际上允许你选择自己想要的游戏类型……《吉他英雄》和《摇滚乐队》并非简单的“休闲”、“硬核”或者介于这两者之间的体验,但却代表了一种允许玩家决定游戏玩法类型的灵活设计。

玩家是定义游戏体验这一准则中最重要的因素,可以在不同游戏中选择自己的玩法风格。那些最终为每位玩家创造独特体验的游戏与玩家之间的关系有所不同,因为玩家与游戏互动的时长不同,背景不同,玩特定游戏的动机也不尽相同。

游戏

虽然玩家在游戏体验定义中占据最大比重,但游戏仍然是定义休闲与硬核体验的一个极为重要的考虑因素。将游戏想象成一个操场。设计这个操场的人无法决定孩子们(玩家)会在上面玩什么游戏,正如电子游戏开发者无法决定玩家如何操作他们的游戏一样。现在,操场的设计师可能会提供一个迂回路线,供儿童注销的攀吊架,以及成套秋千等令儿童更易或更难玩特定游戏的设施,但他们永远不会限制特定游戏的玩法风格。这对电子游戏开发者及其游戏玩家来说也一样。以“模仿式界面”开发一款游戏(游戏邦注:模拟屏幕上内容的实体活动,例如《吉他英雄》、《热舞革命 》、《Wii Sports》等)正如Juul所言,这些游戏提供了一个更为休闲体验的场所,但并没有决定玩家何时能够在掌握游戏中获得硬核体验。

被《PC gamer》杂志誉为25大“游戏之神”之一的设计师Steve Meretzky曾在2007年的游戏开发者休闲游戏峰会上作了一番介绍,指出休闲游戏具有一些特点:容易学习,宽容,时间短暂,极具的重玩性,快速载入以及非暴力性的主题,并且不太昂贵。虽然许多休闲游戏的确包含这些特征,但这并无法将游戏定义为休闲的,因为这取决于玩家的选择。但如果游戏确实包含所有的这些特点,那就是个更适用于休闲体验的场所。

像《星际争霸》这种即时战略游戏(RTS)以及像《魔兽世界》这种大型多人在线角色扮演游戏(MMORPG),就因其题材的需要而呈现更为硬核的体验。RTS和MMORPG由于其题材需要玩家掌握特定的先决知识以及最小时间投入以便获得相关经验,所以更倾向于提供硬核体验的场所。你可以进入《魔兽世界》,只是在里面乱跑10分钟,但你的经验不会有什么实质作用,因为在游戏中做任何事情,例如完成任务,就需要最小的时间投入,这令其更难以呈现休闲体验。

作为场景的游戏影响着玩家所选择的体验类型。在你的网页浏览器中玩Facebook游戏,提供的是完全不同于在主机上玩游戏的场所。在掌机任天堂3DS或者在游戏PC上玩最新的《使命召唤》这种体验也是不同的。这些游戏场所会对玩家所选择的体验产生影响,但它们无法决定这种体验的类型。

Jull指出,游戏像音乐或其他故事形式一样,具有围绕在四周的“牵引力”这种概念。“牵引力”就是玩游戏、制定下一步,或者找到特定角色发生什么情况的需求。“牵引力”可以帮助我们确定哪个场所更适合休闲体验,因为它们通常拥有更强的牵引力。

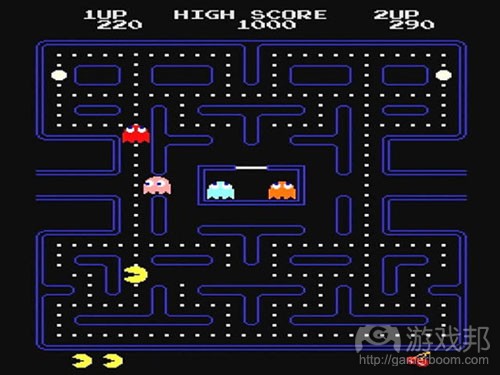

虽然你知道七巧板谜题的游戏要求,并且也很可能知道怎么玩《吃豆人》,但像《星际争霸》这种现代游戏却是不同的。并非人人都能感受到牵引力:并非人人都知道怎么做,并非人人都想拿起游戏开始玩。

“牵引力”代表游戏中的公分线这一理念。如果某款游戏中的“牵引力”对多数人来说都很明显,那么它通常就会拥有更为简单的游戏机制,并且更倾向于休闲模式。继续Julu所举的例子,如果你向其他任何年龄层的人展示以下的《吃豆人》截图,他们可能都会知道怎么走下一步,并且想走那一步。

但如果你向人们展示以下的《星际争霸II》截图,多数人可能都不知道下一步该怎么操作。这是因为《星际争霸II》是比《吃豆人》更为复杂的游戏,更适合硬核体验。

Mikel Reparaz曾在一篇题为《硬核游戏之死》》的网络文章中指出:

休闲游戏通常定义为容易进入,并且制作成本相比较不昂贵的简单游戏。数年来,这些游戏最大的用户群体在PC平台上,像《美女餐厅》和《Cake Mania》这种可下载游戏更能取悦多数有意打发时间而非杀戮怪兽的年长女性群体。

从这一定义来看,Reparaz在这一文章中提到了休闲游戏的数种刻板印象,例如简单、昂贵、用于打发时间。但Reparaz并没有提到一个额外的重要印象:休闲游戏是针对女性行为的场所,将硬核游戏视为男性行为的场所。

休闲与硬核领域中的性别

正如休闲与硬核游戏、玩家所存在的刻板印象一样,这里也存在一个与游戏体验相关的性别刻板印象。富有竞争性的第一人称射击游戏(例如《光晕》和《使命召唤》)因为极具代表性的硬核男性玩家基础而得名,而休闲领域则被标榜为女性化的场所。虽然正如前文所言,因为某一游戏更倾向于休闲体验场所,并不意味着玩家就只能拥有这一种体验。Mia Consalvo在她的论文《Hardcore Casual: Game Culture Return(s) to Ravenhearst》中分析了一款更为休闲的游戏(名为《Mystery Case Files: Return to Ravenhearst》)发布。她发现在休闲社区中的玩家会制作攻略,交互式地图,视频指南等,但最令人意外的是这一社区基本上是清一色的女性。Consalvo继续写道:

显然,许多休闲游戏玩家从其玩法或思维方式来看并不全是休闲性的。至少有些玩家在新游戏中投入程度极高,会讨论过去与未来游戏的不同观点,解决某些游戏所提供的谜题。他们可能组成一个社区,帮助不同游戏中的玩家解决补丁问题,创造了提供支持和建议的宝贵场所。他们还可能采取额外措施,为他人创造可下载地图,深思熟虑地评价或讨论不同游戏的观点,创造与游戏相关的内容,例如同人小说来延伸自己和其他玩家的乐趣。

《Mystery Case Files: Return to Ravenhearst》究竟是不是更为休闲体验的场所,或者该社区是否多为女性这一点已经不重要了——该社区仍然因这些如此投入的玩家而创造了极为硬核的体验。正如一般情况所言,所有手机游戏都是休闲的,或者所有第一人称射击游戏都是硬核的,我们也可以说某一性别是休闲或硬核的。但富有话语权的少数群体,以及营销公司,却是让这些刻板印象深入人心的关键所在。Soderman指出:

在过去5年左右,休闲游戏的崛起及其伴生的女性分类已经令(男性化)硬核文化产生了一种明显的焦虑,令这些曾是游戏界宠儿的后者担忧大众消费群体和休闲玩家最终会扼杀或颠覆硬核游戏。硬核玩家为游戏可能将“降低难度”以及更为简单化的这一趋势而烦躁,那些传统上被视为硬核性的游戏可能也难免这一过程,并吸收休闲游戏原则以便增加自己的用户群体和销量。

虽然这种刻板印象仍然存在,但玩家才是决定自己究竟要休闲还是硬核体验的主体,无论他们究竟是什么性别。

总结

游戏无法迫使玩家以特定方式执行操作。玩家与游戏互动的体验,无论是休闲还是硬核的,全部取决于玩家。玩家可以随着时间的变化,逐年甚至是一年之内就将自己的体验改为休闲或硬核。玩家具有进步的能力。Juul在自己的书中发表了玩家改变游戏习惯这一体验的调查内容:

以下受访者是40岁左右的中年女性玩家。

Q:你在过去数年是否曾改变过游戏习惯?

A:我曾经只玩像《激战》这种RPG,但休闲游戏却可以让你轻松开始或结束。

以下受访者是38岁的男性玩家。

Q:你在过去数年是否曾改变过游戏习惯?

A:随着我年纪增长和责任的增加,我投入大型游戏的时间和耐心越来越有限。虽然我仍然喜欢玩《文明》或《模拟城市》这种史诗般的游戏,但真的无法承受它们所需要的时间。

我们由此可以看出他们曾经的游戏体验是硬核性质的,但由于年岁的增长,他们的生活并不允许这种高投入的体验,因此转向了更为休闲的体验。通常这种情况发生于大学时代,因为这个时期人们会面临更多新鲜事物,其中有许多事情所需要的投入时间会让你的硬核游戏体验让步。

玩家与游戏的每次互动都会创造一种体验,这正是为何确定一种体验是休闲还是硬核的准则能够站得住脚的原因。玩家不断变化,他们玩游戏的动机也在变化,游戏只是玩家表现的场所。这正是我们为何无法确定玩家或游戏是休闲或硬核性质的原因。(本文为游戏邦/gamerboom.com编译,拒绝任何不保留版权的转载,如需转载请联系:游戏邦)

Devising a formula for defining ‘casual’ and ‘hardcore’

- Brian Keschinger

The medium of video games is very young in comparison to other related facets of entertainment, like film, literature, and music. As the medium has grown older, two descriptors have emerged in relation to its players and games: casual and hardcore. This paper is intended to criticize how the definitions of casual and hardcore games and players are produced.

As games have evolved, they’ve become more complicated with each game growing on the conventions of the last. With games becoming more complex, the gaming community has split into two different groups: the casual and the hardcore. Braxton Soderman defines casual games as being played in short bursts by women in order to kill time (332¹). And Michael Samyn asserts hardcore games as competitive elements played by teenage boys (The Contradiction of Linearity²).

These stereotypes have strengthened over the years and are more prevalent in today’s gaming culture than ever before. Publishers use the stereotypes as marketing ploys, developers produce games for one specific subculture, and gamers don’t like to be mislabeled as one term when they self-define themselves as the other. But there are problems with defining these stereotypes, whether being generated from the community or scholars: the lines between casual and hardcore players are blurred, and the attributes between a casual and hardcore game are not clearly separable.

Both of these reasons leave too much grey area when defining the player or game as casual or hardcore. This is because the definitions in relation to the player and game are loose and circumstantial to each individual experience. But the interaction between the player and game produces an experience that I argue can be characterized as hardcore or casual. Deciding whether the experience is casual or hardcore solely relies upon how the player chooses to play the game. Games are only the site for which the player performs; they can’t dictate what kind or style of play occurs.

The definitions of a casual or hardcore “experience” can withstand much more stress because these definitions are more concrete than those of casual or hardcore players and games. The formula for the experience definition, relies on two factors: the player and the game. The player interacting with the game produces the experience, but the formula isn’t weighted evenly between the player and the game. The player is the primary factor in the formula, almost entirely dictating what the experience will be. Yet the game still matters in the formula for it is the site where the player produces the experience.

Defining a player or game as casual or hardcore is very tentative because there are many ways to play a given game. The stereotypical, middle-aged woman can create casual play by fooling around inHalo just as easily as the stereotypical, teenaged boy can create hardcore play by playing Candy Crush to be the best in the world. Even though the definitions of games and players as hardcore or casual crumble very easily, they’re important to discuss as pieces to the sturdy definition of casual and hardcore experiences. In the next section I will discuss the role of the player, followed by a section on the game examining why it merely provides a set of tools for playing and is strictly a site for player performance, all the while explaining how each factor relates to defining a casual or hardcore experience.

The player

The player drives the definition of the experience, for he or she is the one to decide how to play the game. The player makes many decisions, conscious and subconscious, as to how much time to invest in the game and what his or her intentions are for playing the game.

If the player chooses to play the game for hours on end, this would almost demand a hardcore experience. On-the-go gaming is on the other end of that scale. If the player is playing a game on his or her cell phone on the bus on the way to work, this is a much different, and more casual, experience than that of the player marathoning a game. The difference of time investment also introduces another question: Is the player spending time or killing time while playing the game?

Killing time versus spending time is an important dichotomy when considering time in the modern era of gaming. Mobile gaming, with the evolution of cell phones, is available to almost anyone at any time during the day. Soderman, in his dissertation Interpreting Video games through the Lens of Modernity, writes:

casual games in general are often framed in terms of killing time as one waits-waiting for an infant to wake up from a nap, for a commuter train to arrive at the station, for a colleague to arrive for a work meeting, etc. (332)…It is often noted that casual games are played during work when one takes a short break in order to -zone out or reduce stress (Brightman), but these games can certainly be played at home (or anywhere for that matter if one uses a mobile phone)(326).

If the player engages a game to waste time while waiting for some time-constrained event in his or her life to be over, then this is a casual experience. In a hardcore experience, the player would spendtime inside the game exploring, interacting, watching, and possibly even competing. This is not to say that all on-the-go gaming is casual, but it is a much more apparent site for such an experience. The player could be playing Candy Crush, a popular match-three game, on a cell phone while commuting to work with the intentions of getting the highest score in the world. Even though most experiences when playing Candy Crush are casual, this particular example would produce a hardcore experience.

The intention of the player is the other factor, besides time, that defines the player. Continuing with the previous example, if the player intended to get the world’s best score in Candy Crush and played the same level over and over for that sole purpose, then this is a hardcore experience. But if by some stroke of luck, the player was just killing time on the way to work and happened to have received the world’s best score in Candy Crush, then this is a casual experience. Whether the game is Candy Crush,Call of Duty, StarCraft, or Cooking Mama, playing it for sport automatically results in a hardcore experience no matter what. The competitive nature of trying to win when playing the game is hardcore. If the player were playing the game for social purposes, this is typically a casual experience. Jesper Juul, in his book A casual Revolution: Reinventing Video games and Their players³, describes how the intentions of the player in the same game can affect the experience that is produced:

[Guitar Hero and Rock Band] are different depending on the goal you set as a player. If you seek to play the game as a social event, you can play the game one song at a time. In this case, the game requires only marginal time investment, making it closer to casual game design principles. If, on the other hand, you play the game with the goal of mastering it, you will be replaying the same song over and over, and you will be memorizing the specific button presses needed to complete a song. In this case, the game is closer to traditional hardcore game design principles (142).

The social nature of games like Guitar Hero and Rock Band makes it easier for a casual experience, but it is the player’s intentions when playing the game that define the experience. Those two games fall into a loose category of games without goals or ones with optional goals. For instance, the popularGrand Theft Auto series is usually considered a site for a more hardcore experience with its large, open worlds, hours of narrative, and skill required to play, but because of the design where the goals of the game are optional, casual experiences are easy to have in this series as well. Juul goes on to explain that:

games without goals or with optional goals are more flexible: they accommodate more playing styles and player types, in effect letting you choose what kind of game you want to play (138)…Guitar Hero and Rock Band are therefore not simply ‘casual,’ ‘hardcore,’ or somewhere on a scale between the two, but represent a kind of flexible design that lets players decide what type of game to play (129).

The player, the most important factor in the formula for defining the experience, chooses his or her style of play from game to game. There are different relationships between the player and the game that ultimately produce a unique experience for every player, as they interact with each game for different amounts of time, in different settings, with different intentions for playing each particular game.

The game

Though the player carries most of the weight for the definition of the experience, the game is still a very important factor for determining whether the experience is casual or hardcore. Think of the game as a playground. The people who designed this playground can’t dictate what kinds of games children (the players) will play on it, just like developers of video games can’t dictate how players use their game. Now, the designers of the playground may provide a roundabout, monkey bars, and a swing set, which make it easier or harder for children to play certain types of games, but they will never be able to limit the kind or style of play to a specific game. This is the same for video game developers and the people who play their game. Developing a game with “mimetic interfaces” (games where physical activity mimes what happens on screen, i.e. Guitar Hero, Dance Dance Revolution, Wii Sports, etc.), as Juul calls them, offers a site for a more casual experience, but doesn’t dictate when the player is able to have a hardcore experience in mastering the game.

Steve Meretzky, a game designer who PC gamer magazine named as one of its 25 “Game Gods,” gave the introduction to the casual games Summit at the game Developers Conference in 20074. In his introduction, he stated casual games have certain characteristics: easy to learn, forgiving, short playing time, highly replayable, quick loading and starting, non-violent themes, and inexpensive. Though many casual games do contain these characteristics, these can’t define the game as casual, as the player could have a hardcore experience if he or she chooses to do so. But if the game does contain all of those characteristics, it is a much more conducive site for the casual experience.

Real-time strategy (RTS) games, like StarCraft, and massively multiplayer online role-playing games (MMORPG), like World of Warcraft, are known for being sites for the more hardcore experience mostly because their genres demand it. RTS games and MMORPGs are a more likely site for the hardcore experience because their genres require certain prior knowledge to have an experience and a minimum time investment for having an experience. You could jump into World of Warcraft for only 10 minutes to run around, but your experience won’t be substantial because actually doing anything in the game, like completing quests, requires a minimum time investment, making it more difficult to have a casual experience with this game.

The game as a site influences the experience that the player chooses to have. Playing a game in your web browser on Facebook offers a completely different site than playing a game on your console. The same goes for the experience available when playing on your handheld Nintendo 3DS or playing the latest Call of Duty on your up-to-date gaming PC. These play spaces are influential to the experience available for the player, but again, they cannot dictate the experience that is had.

Juul says that games, like music or other story forms, have this notion of ‘the pull’ surrounding them. ‘The pull,’ is this need to play the game, make the next move, or find out what happens to a group of characters. ‘The pull,’ can help us decide what is a more likely site for the casual experience is as they usually have a stronger pull.

While it is fairly certain that you know what a jigsaw puzzle asks of you, and there is a high chance that you know what to do with the game of Pac-Man, a modern game like StarCraft is divisive. Not everybody feels the pull: not everybody knows what to do, not everybody wants to pick up the game and start playing (4).

‘The pull’ represents the idea of a common denominator in gaming. If ‘the pull’ is apparent in a particular game for most people then it is usually has much more simple game mechanics and strays toward the casual end of the scale. Continuing with Juul’s example, if you showed the screenshot below of Pac-Man (Figure 1) to just about anyone, of any age, they would know what move to make next and want to make that move.

Pac-Man, Figure 1

But if you showed the screenshot below of StarCraft II (Figure 2) to people, most wouldn’t know what move to make next. This is because StarCraft II is a much more complex game than Pac-Man, making it a more likely site for a hardcore experience.

StarCraft II, Figure 2

Mikel Reparaz wrote in an online article entitled The Death of hardcore Gaming?5:

Casual games-usually defined as simple games that are easy to get into and relatively inexpensive to make-have been with us for a long, long time. For years now, their biggest audience has been on PCs, where downloadable games like Diner Dash and Cake Mania entertain a mostly older, female demographic more interested in killing time than in killing monsters.

In this definition, Reparaz addresses several stereotypes of casual games that have already been discussed in this paper, such as being simple, inexpensive, and used for killing time. But Reparaz does bring up an additional, important stereotype: casual games are a site for femininity and implying that hardcore games are a site for masculinity.

Gender in the realm of casual and hardcore

Just as there are existing stereotypes for both casual and hardcore games and players there is an existing stereotype for gender in relation to the experience. Competitive first-person shooters, likeHalo and Call of Duty, are known for their stereotypical hardcore male player base, while the casual scene has been pinned as a place for femininity. Though, as previously stated, just because a game is a more likely site for the casual experience doesn’t mean that experience is always the one to be had. Mia Consalvo in her paper Hardcore Casual: Game Culture Return(s) to Ravenhearst analyzes the release of a particular, more casual game, titled Mystery Case Files: Return to Ravenhearst on the game’s forum. In her following of the all-but-casual community, they were making walkthroughs, interactive maps, and video guides, but the most surprising thing was that the community was almost entirely female. Consalvo goes on to write:

Clearly, many players of casual games are not at all casual in how they play or think about such games. At least some players are heavily invested in anticipating new titles, discussing various aspects of past and future games, and solving the mysteries that some games provide. They likewise form a community of sorts, helping other players with rough patches in various games, creating valuable sites for support and advice. They can also take extra steps, creating interactive downloadable maps for others to use, thoughtfully reviewing or discussing aspects of various games, and creating game-related artifacts such as fan fiction to extend theirs and other players’ enjoyment.

It didn’t matter that Mystery Case Files: Return to Ravenhearst was a more likely site for a casual experience or that the community surrounding it was mostly female — the community still generated a very hardcore experience by becoming so invested in the game. Just as it is circumstantial to say that all mobile gaming is casual or that all first-person shooters are hardcore, it is circumstantial to say that one gender is casual or hardcore, too. But a vocal minority, along with marketing companies, is keeping these stereotypes relevant. Soderman points out that:

In the last five years or so the rise of casual games and its concurrent gendering as feminine has ignited a palpable anxiety in (masculine) hardcore culture where these gamers-once the darlings of the gaming industry-worry that the mass consumer and the casual gamer will kill or overrun the hardcore. The hardcore gamer frets that games will be -”dumbed down” and increasingly simplified, a process that supposedly will not ignore titles traditionally viewed as hardcore as these too will absorb principles of casual gaming in order to increase their audience and distribution (301).

While the stereotypes still remain, it is up to the player to decide if they are to have a casual or hardcore experience, no matter what their gender is.

Conclusion

The game cannot force the player to perform their play in a any specific way. The experience of the player interacting with the game, casual or hardcore, is entirely up to the player. The player is not a concrete being that is set in his or her ways. He or she can change his or her experience from casual to hardcore, or vice versa, over a set of years, from day to day, or even within a single play session with one game. The player has the ability to evolve, and he or she usually does. Juul, in his book, conducted several sets of surveys asking players about their experience with their changing habits.

Survey response from a 40-year old female player.

Q: Have your game-playing habits changed over the years?

A: I used to only play RPGs like Guild Wars but you can start and stop casual games easier during the day (162).

Survey response from a 38-year old male player.

Q: Have your game-playing habits changed over the years?

A: As I grew up and had more obligations my time and patience became limited towards investing in epic games. Though I still love the idea of playing epics like Civilization or Warlordsor SimCity, the time required is just more than I can provide (163).

We can see that their usual experience with games used to be hardcore, but as they grew older their lives didn’t allow for such a demanding experience which is why it changed to a more casual experience. A typical time in one’s life for this to happen is during college. The college fallout from the hardcore experience with gaming is typical because you become exposed to many new things, a lot of which require the time you once spent Experiencing games in a hardcore way.

Each individual interaction between the player and the game creates an experience which is why the formula for determining whether an experience is casual or hardcore holds up. The player is constantly changing, along with their intentions for playing, and the game is only the site for player performance. This is why we are unable to state that a player or game is casual or hardcore. It is the product of the two, the experience, that is casual or hardcore. (source:gamecareerguide)

上一篇:如何在游戏设计中发挥活动的威力

闽公网安备35020302001549号

闽公网安备35020302001549号