举例分析游戏奖励的心理学原理

作者:Max Seidman

在过去2年里,我有幸在Tiltfactor与Geoff Kaufman博士一起工作,他是社交心理学领域的哲学博士,也是我们的实验室研究的的领导者。除了具有一些独到的见解外,他也对我们所开发的一些游戏进行了正式的研究,我也学到了许多有关心理学的内容,并形成了许多有关它是如何影响游戏的理论,同时还列出了游戏设计师们必须牢记的一些要点。最近我投入了大量时间去研究游戏设计中一个备受争议的心理话题,即奖励安排,以及这与心理学家所谓的“过度合理化效应”有何关系。如果你从未听说过这些内容也没关系!我将在讨论它们对于游戏设计师的意义前先进行解释。

显然这些理论都适用于数字游戏和桌面角色扮演游戏,所以所有类型的游戏设计师都需要理解它们,特别是在传统桌面游戏和纸牌游戏日趋数字化的时代里。

奖励安排

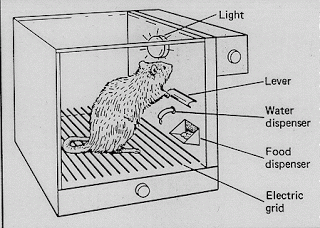

在20世纪30年代,哈佛大学的一位心理学家Burrhus Frederic “B. F.” Skinner创造了一个操作性条件反射室(游戏邦注:也就是著名的“斯金纳箱”)。该理念很简单:将一只老鼠放在箱子里。让老鼠拉动箱子里的杠杆。有时候提供给老鼠一些食物让它去拉动杠杆。研究怎样的条件能让老鼠更频繁地拉动杠杆。

当然,斯金纳箱也包含冲击生物的能力,因为科学家就是这样的。

当你着眼于斯金纳箱与其它心理学家发现什么时,这一应用在游戏设计中将变得更加明确。在鸽子身上做实验的时候,研究者发现当鸽子只有一次接收奖励的机会时,它们会更频繁地推动刚刚。当它们获得奖励的机会是50%时,它们是最活跃的。这是一种间歇式奖励安排:这将给予任何特定的行动一次回报机会。研究中发现最有效的奖励安排是基于可变比例的奖励安排—-即将随机性插进等式中,如存在许多没有报酬的拉杠杆行动,但平均报酬却是固定的。

如果这一行为能够延伸到人类身上(说实话,是可以的),那么基于获得奖励的机会而不是有保证的奖励,我们便会更频繁地去执行一个活动。我们将会凭借直觉去掌握这点:这也是我们为什么会赌博。许多游戏已经使用了这些原则。举个例子来说吧,老虎机便是将“斯金纳箱子”理念带到了人类身上。Zynga因为在像《FarmVille》等社交游戏中使用可变比例的奖励安排而出名。甚至连《魔兽世界》也使用了这一理念,即让玩家不时杀掉mob而获取任务中所需要的战利品。

游戏设计众多 可变比例奖励安排的使用经常因为太过“邪恶”而遭遇批评。批评者的观点是:如果游戏设计师选择使用简单固定的奖励安排(即每个行动都伴随一个承诺奖励),玩家将只会玩一阵子。而面对可变比例奖励安排,玩家将更加活跃。因此游戏设计师是在“欺骗”玩家去玩更多他们真正想要玩的,并为此花更多钱。

在正式进入游戏中使用的可变比例奖励安排前,我想要说说在道德和奖励安排讨论中经常被忽视的另一个主要现象:过度合理化效应。

过度合理化效应

1973年,心理学家Mark Lepper和Richard Nisbett与幼儿园教师合作组织了一次有趣的实验。他们观察到孩子们会受到内在的激励去画画—-孩子们喜欢根据自己的想法去画画而不需要获得任何额外的报酬。他们将孩子们分成三个群组。他们承诺给予第一个群组的孩子缎带作为画画的奖励。也给予第二个群组的孩子缎带奖励,但却未事先说明。而第三个群组的孩子则独自在那边画画。尽管使用了缎带奖励,但所有三个群组的孩子们都交出了基本上相同数量的图画。之后他们不再提供缎带奖励。第三个群组的孩子就像他们预期的那样继续画出同样数量的图画(毕竟对他们来说什么都未发生变化)。而第一个群组的孩子在图画数量上却出现了大幅度的下降。

于是心理学家推断出,当第一个群组的孩子接收到缎带奖励时,他们的动机便从“我是因为喜欢画画而画画”(内在想法)转变成“我是因为想得到缎带而画画”。只要他们仍能收到缎带,他们就会继续画画,但一旦不再受到奖励,他们也不会再回到原先的想法了。

这是许多游戏类型经常忽视的情况。我只想分享自己亲身经历的一个例子,但如果你玩过许多电子游戏,我敢保证你将能够识别何时出现过度合理化效应。

对于我而言,在《暗黑破坏神3》中获取胜利后,我仍继续游戏,并在拍卖行中卖掉了我的稀有道具。我创建了一个出售稀有道具的商店,并在此慢慢将道具卖掉。基于这种方式我玩了好几周的游戏,但之后情况开始发生改变:暴雪发行了一个补丁,让新掉落的稀有道具变得更加强大。这让我所收集的所有道具都变得不再那么有价值,于是在阅读了这一补丁说明后我便退出了游戏。并到现在都未曾再接触游戏。这里所出现的情况是,我的动机从“我希望玩《暗黑破坏神3》”转变成“我喜欢在拍卖行中出售道具。”所有的一切在暴雪剥夺了我通过自己的努力赚钱的机会前都是很完美的。

在另外一个例子中,我玩的是《英雄联盟》,即始终致力于打开一个召唤师咒语:有名的“Flash”咒语。一旦我打开它,我便退出游戏。甚至在那之后我都未曾再玩过一次游戏。我的游戏动机从单纯地玩游戏变成了“想要打开Flash”,而一旦我做到了这点,我便发现自己不再有游戏动机了。

在这两个例子游戏,游戏都呈现给我一个目标,并逐渐破坏我玩游戏的最初想法。从设计师的角度看来这是合理的,即只要仍保留着外在动机(奖励)就足够。只要我能继续在《暗黑破坏神3》的拍卖行中出售道具,我便会继续游戏。但不幸的是,这里存在两个显著的情况将带走玩家的奖励。最简单的一个例子便是我在《英雄联盟》中的遭遇。另外一个问题就是我在《暗黑破坏神3》中经历的,即奖励逐渐过时。在这两个问题间,设计师很难在避免过度合理化效应的情况下将固定奖励安排带进游戏中。

提供奖励

在游戏中提供奖励是受欢迎的。设计师会因为各种理由给予玩家奖励,包括讲话他们的行为,提供玩家的精通感,在某一游戏过程中提升难度,支撑游戏机制和玩家能力等等。所以设计师该如何在冒着过度合理化威胁日常开支并有可能导致玩家失去对游戏兴趣的风险下提供奖励?Lepper和Nisbett在幼儿园实验中的第二组孩子便为这一问题提供了一个暗示。这一群组将在画画后获得缎带奖励,但之前却不清楚奖励的存在。在之后一旦奖励被删除,这一群组将与第一个群组基于同样的速度画画。

这能让设计师在避免将玩家动机转变成想要奖励的前提下知道该如何提供奖励。不要让玩家知道他将获得奖励—-这也被称为一种可变的奖励安排。这很直接:当玩家知道自己将获得奖励时,他便只会为了奖励而游戏。这比当奖励是不确定时转变动机更加困难。这也是为何像《魔兽争霸2》等游戏会在一些难以预测的时候给予玩家道具作为奖励的主要原因:如此玩家便可以无需依赖于奖励而好好享受游戏乐趣了。

在这里我的要点不只是澄清可变比例奖励安排不是一种内在的邪恶方法,同时还想说明它们其实是一种优秀的游戏设计实践。可变比例奖励安排并未欺骗玩家去尝试更多他们并不想玩的内容,它们是通过欺骗玩家的大脑而阻止他们从原本的游戏理由转变成外部元素。这便意味着这些奖励安排将保持玩家继续游戏,并且是因为他们发现了体验本身的乐趣,而不只是为了获取奖励,这才是真正的游戏设计!游戏设计是创造玩家能够与乐趣互动,并且无需外部理由便能够呈现出价值的系统的过程。当能够包含可变比例奖励的时候却忽略它们便等于忽略了其它已建立起来的设计理论:这只是一种卑劣的设计实践。

设计师是否能够滥用奖励安排的心理学原理?当然!大多数人的心理原理通常都会被滥用。甚至在使用心理学原理“欺骗”玩家去感受更多乐趣也算是给予玩家更多乐趣。

(本文为游戏邦/gamerboom.com编译,拒绝任何不保留版权的转载,如需转载请联系:游戏邦)

The Psychology of Rewards in Games

by Max Seidman

Over the past 2 years I’ve had the privilege of working with at Tiltfactor alongside Dr. Geoff Kaufman, who has a PhD in social psychology and is our head of research at the lab. In addition to the fantastic insights he has made running formal studies on the games we’ve been developing (publication pending on those), I’ve learned amazing things about psychology, formed many theories about how it influences game playing, and developed a list of things game designers need to keep in mind. I’ve devoted a lot of thought recently to one of game design’s most hotly debated psychological topics, reward schedules, and how they relate to what psychologists call the “overjustification effect.” But don’t worry if you’ve never heard of either of these things! I’ll explain them both before discussing what they mean for game designers.

These theories, while most obviously applicable to digital games and tabletop roleplaying games, are important for all types of game designers to understand, especially in an era where even traditional board and card games are becoming more digital.

Reward Schedules

In the 1930s, Burrhus Frederic “B. F.” Skinner, a psychologist at Harvard, invented an Operant Conditioning Chamber (better known as a Skinner Box). The concept was simple: put a rat in the box. Let the rat pull the lever in the box. Sometimes give the rat a food pellet for pulling the lever. Study what conditions cause the rat to pull the lever more or less often.

Of course Skinner Boxes also include the capacity to shock the creature because scientists are freaky like that.

The applications in game design become clear when you look at what Skinner and other psychologists found. While experimenting with pigeons, researchers found that the pigeons were more likely to push the lever more often when there was a only a chance that they would receive a reward, even more often than when they always received one. Specifically, they were most active when the chance of receiving a reward was 50%. This is an intermittent reward schedule: it gives a chance at payoff for any given action. Specifically, they found that the most effective reward schedule was a variable ratio reward schedule – inserting randomness into the equation such that there could be many pulls of the lever with no payoff, but the average payoff is set.

If this behavior can be extended to humans (and let’s be honest, it can), we can be controlled to perform an activity more often simply by giving us a chance at a reward instead of promising us a guaranteed reward. We tend to know this intuitively: it’s why we gamble. And tons of games already use these principles. For example, slot machines are basically Skinner Boxes for humans. Zynga is notorious for using variable ratio reward schedules in their social games like Farmville. Even World of Warcraft uses them by having killed mobs only drop the loot you need for quests some of the time and not all of the time.

Skinner Box for people

The use of variable ratio reward schedules in game design is often panned, however, for being “nefarious.” Detractors’ reasoning goes: if the game designers had chosen to use simple fixed reward schedules (where for each action there is a promised reward), the players would play a certain amount. With variable ratio reward schedules, the players are more active. Thus, the game designers are “tricking” the players into playing more than they really want to, and usually also spending money.

Before I go into the ethics of using variable ratio reward schedules in games, I want to talk about another crucial phenomenon that is often overlooked in discussions of morality and reward schedules: the overjustification effect.

Overjustification

In 1973 psychologists Mark Lepper and Richard Nisbett conducted a fascinating experiment with kindergarteners. They observed that the children were intrinsically motivated to draw —that the kids enjoyed the activity of drawing pictures for its own sake without any need for external payoff. They split the children into three groups. The students in the first group were promised ribbons as a reward for drawing. The students in the second group were given ribbons, but were not promised them beforehand. The third group was left alone to draw in peace. While the experimenters handed out ribbons, all three groups drew comparable amounts of drawings. Then they stopped giving out ribbons. The third group, as would be expected, continued to draw the same amount (after all, nothing had changed.) The first group, however, had a significant drop off in the amount of drawing they did.

Psychologists theorize (and they’re pretty certain at this point) that what happened is as the first group received ribbons, they shifted their motivations from “I’m drawing because I like drawing” (intrinsic) to “I’m drawing because I want a ribbon.” They were still motivated to draw so long as they were receiving their rewards, but once the rewards were removed the motivation did not snap back to being intrinsic.

This is an often overlooked phenomenon that occurs in many sorts of games. I only have personal anecdotes to share, but if you play many video games I’m sure you’ll be able to identify times when the overjustification effect happened to you.

For myself, after beating Diablo 3 I continued to play and sell my rare items for money on their real money auction house. I built up quite a store of rare items that I was slowly selling off. I played this way for several weeks, but then something changed: Blizzard released a patch making newly dropped rare items much more powerful. This made all of my collection worthless, and I quit after reading about the patch. I haven’t played since. What happened here was I shifted my motivation from “I like playing Diablo 3” to “I like selling items on the auction house.” This was all well and good until Blizzard took away my chance to cash in on my efforts, and then I simply quit.

In another personal example, I played League of Legends, all the while working towards unlocking a single summoner spell: the renowned “Flash” spell. As soon as I unlocked it I quit. I didn’t even play one game with it unlocked. I had shifted my motivation for playing the game to “I want to unlock Flash,” and as soon as I did I found I had no motivation left to play.

Cue 1000 screaming fan boys on how overpowered Flash is and how I should totally play with it.

In both of these cases the games presented me with a goal to work towards that undermined my intrinsic desire to play the game. From a designer’s point of view this is fine, so long as the extrinsic motivations (rewards) remain. So long as I could continue selling items on the Diablo 3 auction house, I would keep playing. Unfortunately, there are two obvious occurrences that take players’ rewards away. The simplest one, exemplified by my League of Legends story, is that the player can achieve the reward. The other problem, as shown in my Diablo 3 anecdote (and many others) is the reward becoming obsolete. Between these two issues it’s difficult for a designer to add fixed reward schedules into a game without risk of the overjustification effect coming into play.

Giving Rewards

Giving rewards in games is desirable. Designers want to give players rewards for numerous reasons, including reinforcing player behavior, increasing players’ feelings of mastery, scaling difficulty over the course of gameplay, and scaffolding mechanics and player abilities. So how can designers give rewards with the perils of triggering overjustification looming overhead and threatening to make their players lose interest in the game? Lepper and Nisbett’s second group of kindergarteners (the group I didn’t reveal the results for) give us a hint at the answer. Recall that this group was the one that were given ribbons after drawing, but were not promised them beforehand. Once the rewards were removed, this group continued to draw at the same rate as group number one.

This gives designers the solution to providing rewards while avoiding shifting players’ motivations to solely wanting rewards! Don’t let the player know for certain that she’s going to get a reward —also known as variable reward schedules. It’s pretty straightforward: when a player knows what she’s going to receive by means of a reward, she can play only for that reward. It’s much harder to make that motivational shift when the reward is uncertain. This is why games like Dota 2 give items as rewards after games fairly infrequently, at (almost) unpredictable times and with random quality: this way players can enjoy the surprise of the reward without banking on it.

Dota 2 gives payoffs when the “battle experience” bar up at the top fills up. I couldn’t for the life of me tell you how many battle points I have, which means it’s as good as random and Valve is doing a great job!

My point here is that not only are variable ratio reward schedules not inherently evil, they are actually good game design practice. Variable ratio reward schedules don’t trick players into playing more than they really want to, they trick the players’ brains to prevent them from shifting their justification for playing to external factors. This means that these reward schedules keep the players playing because they find the experience itself fun and not just to get to the next reward, AND THIS IS EXACTLY WHAT GAME DESIGN IS! Game design is the process of making systems that players find interacting with fun and worthwhile without external justification. Omitting variable ratio rewards when they could be included is just like ignoring other established design theory (say scaffolded learning or positive feed back loops) that we’ve discussed on Most Dangerous Game Design previously: it’s simply shoddy design practice.

Can designers abuse the psychology of reward schedules? Of course! Most of human psychology can be abused and often is. However, even when using psychology, “tricking” players into having more fun still counts as giving players more fun. I know this entire arguments tends to raise peoples’ hackles, so please feel free to argue with us in the comments, as always!(source:mostdangerousgamedesign)

上一篇:硬核社交游戏获得成功的4个要素