阐述LTV在免费游戏中所扮演的角色

作者:Eric Seufert

用户终身价值(LTV)是免费应用开发者最基本的追求理念。尽管计算LTV并将其整合到组织的决策器中是一项艰难的任务,但这并不是开发公司如此重视LTV的根本原因。

真正的原因在于用户获取(特别是其成本),以及只有少数应用能够在发展用户基础时市场营销成本。

用户获取是大多数应用开发者真正担忧的问题:如果他们的应用的LTV为负值,他们的用户基础便不可能增长(除非获得病毒性推广的支持)。但是该理念经常会因为分离的病毒性和付费获取,或者因为使用LTV去推动产品开发,或者将市场营销成本与开发者成本结合在一起而让人混淆。

定义LTV

LTV总是被定义为属于用户的所有未来现金流的现值。实际上,我们总是不清楚如何计算LTV:对于大多数应用开发者而言,将金钱的时间价值与对于用户未来收益贡献的理解整合在一起是不务实的,而这主要存在几大原因。

首先,通过运行手机应用而得到所挣得的金钱的风险调整折现率是不现实的。只有少数最大型的开发者能够将产品运营的收益投资在短期且有趣的证券中,就像短期无息国库券或商业票据;大多数开发者将自己的收益投资于持续开发中,所以我们不能准确计算其真正收益。

其次便是用户在游戏中的投入时间,更重要的是任何独立用户在大多数免费设置中的收益贡献的时间和规模都是一种随机过程,游戏会使用贴现率基于固定的时间轴去调整已知且离散的数值。免费应用的现金流并不像年金或债券的现金流,即具有一致的分散间隔。

为了确保LTV的有效性,我们必须将其作为每用户基础的收益贡献的概率总和进行估算。如此看来估算LTV是一种纯粹的智力实践,即减少了效果营销中最突出的通知过程能力。

LTV是一种市场营销参数

从产品开发角度来看,一特定用户预计会贡献给一个产品的整体金额并没有多大用处;它并不能用于调整产品的盈利机制。同样的,因为LTV是由各种类型的用户群组的特征(游戏邦注:包括地理位置,设备类型,获取资源等等)所汇聚在一起,所以它并不能与整体的产品体验维系在一起。

关于LTV参数的唯一使用案例便是决定是否能够基于正面ROI去执行市场营销活动。这通常是以LTV>CPI的形式呈现出来,即表示用户的预期生命价值高于获取成本。如此,市场营销预算的回报便是正面的。

LTV>CPI

LTV>CPI是关于LTV如何匹配应用开发者广泛的公司策略的困惑之源。LTV是一种市场营销参数而非会计参数;如此,LTV描述的只是应用开发者的业务的一个方面,而不是其整体收益结构。当LTV大于CPI时,公司的市场营销运行便会呈现出正收益—-尽管这从客观看来是有利的,但却不能保证公司的整体收益。

能够描述整体公司收益的术语并非LTV>CPI,而是收益>开支。这两个术语只会在基于逻辑蕴涵时才具有关联性;因为市场营销在公司的整体运营中是唯一的功能域,使用资源是具有工现象,但却并不能决定公司的整体收益。

LTV!=收益

LTV>CPI与收益>开支是不一样的,因为LTV是一种推测;LTV并不能决定用户对于产品的接纳情况,而只是一种估算的时间值。而当用户接受了产品时,CPI便已经被支付出去了。因为LTV和CPI的年表是不同的,所以即使收益并未超过支出,LTV仍有可能赶超CPI。

当然这并不只是局限于LTV或免费游戏的讨论;如果公司销售的是一次性购买产品,那么即使他们能够有效地阻止市场营销,但却不能涵盖所有的运营开支。

在免费环境下,有关LTV讨论的独特之处便在于量的考量以及收益规则性。每用户获取成本将伴随着市场营销活动的规模而提高,而这正是大多数广告活动所采取的拍卖模式的结果:广告商为独立的植入广告,最高的投标将获得广告。在任何特定时间点提供有限的植入广告,如果广告商想要赢得更多竞标,他就需要支付更多的钱。

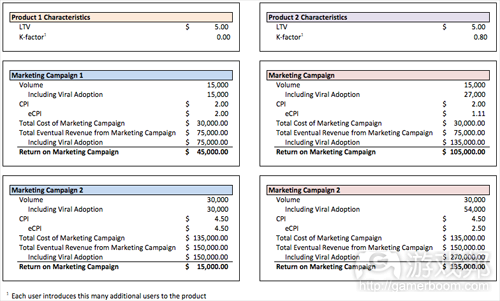

这一关联性影响着公司对于LTV的理解,因为源自用户基础的整体可实现收益是其规模和LTV与CPI间的差距的函数。基于较高的市场容量,逐渐降低的LTV和CPI间的正差幅将拉低利润并越过一定的CPI门槛,如下图所示:

从经济角度来看,公司应该支持能够提升整体利润的市场营销活动,而不顾容量。但是这一角度必须考虑到其它参数的整合,即添加一定深度到评估LTV的环境中:病毒性。

病毒性和LTV

病毒性(也就是k元素)会改变LTV和CPI关系的动态:因为病毒性代表免费发展,它能减少市场营销活动中为每个用户而花费的实际价格。采取相反的方法(即使用k元素去扩大LTV)是不适当的,因为LTV是针对于描述单一用户所创造的收益贡献。

将k元素当成减少产品CPI的一大元素将帮助我们避免陷入病毒性和付费用户获取是相互排斥的这一观点中。

高病毒性产品的确能从用户获取中受益;实际上,比起非病毒性产品,它们能够受益更多,因为减少的eCPA将加速整体市场营销收益开始随着提高的容量而下降的点。在某种意义上,病毒性能够提高市场营销活动的收益曲线,并提高每个利益水平上能够获取的用户数量。

LTV和沉没成本

将LTV作为特定产品的整体收益函数非常诱人,并且能够要求LTV去补偿开发成本。

但是这种思维模式忽视了LTV作为市场营销参数的基本角色。实际上,LTV不应该涉及开发成本:LTV只能用于决定特定时间里的边际用户获取的回报是正数。

为了将LTV从公司整体利润中提取出来,它必须待在市场营销运行参数中:LTV>CPI并不是一种业务策略,它是一种市场营销指令,即在预算范围内做出的指令。因为LTV只是长期收益的近似值,所以在持续的基础上它并不能与支出相匹配。

分离支付包含了LTV是收益道具的理念,并且这必须用于确定公司逐月运行的预算。市场营销开支必须被框定在每月收益数值中,如此才能分配资源到市场营销预算中,如此才能达到增长目标。

尽管通过每用户获取和市场营销道具我们能在免费应用中估算LTV值,但是就像在其它产业中,它基于预算而运行,并仍会处理其它业务范围。

换句话说,免费手机游戏的市场营销并不是LTV和CPI间的无限反馈循环,即只要差幅是正数便会上升;相反的,因为处在传统产业中,所以它是操作马赛克的一个组件,必须对公司的策略做出贡献。

孤立的LTV

因为LTV伴随着无数的机遇,有些很容易被误解和无用,所以将其用于市场营销外部的环境是不可行的(游戏邦注:即使只是描述市场营销过程)。LTV是一个过于广泛的参数,所以不能带给产品开发和管理设置带来多大帮助;相反的,产品经理应该专注于优化传达用户的喜好和用户粘性的参数,如用户留存和针对于产品的活动对策。

LTV参数在产品开发中的滥用可能性越扎越深。大多数产品经理(在了解了一件产品的LTV不足以调节付费市场营销)将为此执行更具攻击性的盈利机制,因为它们会更加明确。用户留存对于LTV的贡献与对于盈利的贡献是一样的—-但是比起专注于增加盈利,专注于用户留存的产品改变更加难以改变用户疏远的情况。

作为源自多种不同输入的概率性参数,LTV并不能有效描写所有内容,除了在评估市场营销活动的情况下。将LTV作为一种业务策略,而不是用于描述公司的一般性能将过分简单化业务的动态性,并模糊有助于成功的实际元素。LTV是一种复杂的理念,但是其用途却不复杂:它将决定是否应该执行某一市场营销活动。

(本文为游戏邦/gamerboom.com编译,拒绝任何不保留版权的转载,如需转载请联系:游戏邦)

The role of LTV in freemium

By Eric Seufert

Lifetime Customer Value is probably the most fundamental conceptual struggle for freemium app developers. And while calculating LTV and integrating it into an organization’s decision-making apparatus are onerous tasks, these aren’t the root causes of firms’ anxieties over LTV.

The root cause is user acquisition – specifically, its cost – and the inability of all but a small minority of apps to recover their marketing spend when growing their user bases.

User acquisition is an existential concern for most app developers: if their apps aren’t LTV positive, their user bases can’t grow absent the auspices of substantial virality. But the concept is often muddied by intellectually segregating virality and paid acquisition, or by using LTV to drive product development, or by conflating marketing costs with the costs of development.

Defining LTV

LTV is commonly defined as the present value of all future cash flows attributed to a user. In practice, this is rarely how LTV is calculated: for most app developers, incorporating the time value of money into an understanding of the user’s future revenue contributions isn’t pragmatic, for a number of reasons.

The first is that deriving a risk-adjusted discount rate for money earned through operating a mobile app is impractical. Only a small minority of the largest developers are positioned to invest the proceeds from operating their products into short-term, interest-bearing securities like treasury bills or commercial paper; the vast majority invest their revenue into continued development, the return on which is impossible to predict with any accuracy.

The second is that the lifetime of a user and, more importantly, the timing and size of any individual user’s revenue contributions in most freemium settings are stochastic processes, whereas a discount rate is used to adjust known, discrete values on a fixed timeline. Freemium app cash flows don’t resemble cash flows from annuities or bonds, which are consistent and distributed on even intervals.

To be useful, then, LTV should be calculated as a probabilistic sum of revenue contributions on a per-user basis. Discounting LTV is a purely intellectual exercise in this context that reduces its ability to inform the process to which it is most appropriate and applicable: performance marketing.

LTV is a marketing metric

The total amount of money a given user can be expected to contribute to a product, as a data point, isn’t useful from a product development perspective; it doesn’t describe product use at a granular enough level to be used to adjust a product’s monetization mechanics. Also, because LTV is aggregated by various demographic characteristics – geography, device type, acquisition source, etc. – it necessarily can’t be associated with the overall product experience.

The sole use case for the LTV metric is determining whether a marketing campaign can be conducted on an ROI-positive basis. This is often expressed in the form of LTV > CPI, which describes a state in which a user’s projected lifetime value is greater than its cost of acquisition. Under such conditions, the return on marketing spend is positive.

LTV > CPI

The term LTV > CPI is the source of much general confusion around how exactly LTV fits into an app developer’s broader corporate strategy. LTV is a marketing metric, not an accounting metric; as such, LTV describes only one aspect of an app developer’s business, not its entire revenue structure. When LTV is greater than CPI, a firm’s marketing operations exhibit positive return – which, while objectively a favorable position, does not guarantee overall profitability for the firm.

The term that describes overall firm profitability is not LTV > CPI, it is Revenue > Expenses. The two terms are related only in their logical implications; because marketing is only one functional domain within a firm’s overall operations, the return on its use of resources contributes to but does not necessarily exclusively determine the firm’s general profitability.

LTV != Revenue

LTV > CPI is not analogous with Revenue > Expenses because LTV is a projection; LTV is not considered realized at the point of a user’s product adoption but over an estimated lifetime. CPI, however, is paid out at the point of a user’s product adoption. Because the chronologies of LTV and CPI are not the same, it is possible for LTV to exceed CPI while revenue does not exceed expenses.

This is of course not unique to a discussion of LTV or freemium; even firms selling one-time purchase products, where LTV is discrete and realized immediately upon adoption, can profitably conduct marketing yet fail to cover their operational overhead.

What is unique to a discussion of LTV within a freemium context are volume considerations and revenue regularity. Cost per acquisition increases with the size of a marketing campaign as a result of the auction model through which most advertising campaigns are conducted: advertisers submit bids for individual ad placements, and the highest bids are awarded the placement. Given a finite number of placements available at any given point in time, the more placements an advertiser wants to win over a specific timeline, the more it must bid for those placements.

This relationship affects a firm’s understanding of LTV because the total realizable profit from a user base is a function of its size and the spread between LTV and CPI. At high marketing volumes, the decreasing positive spread between LTV and CPI can result in reduced profit past a certain CPI threshold, as in the two scenarios presented below.

From an economic standpoint, the firm should favor the marketing campaign that produces the greatest level of overall zbprofit, regardless of volume. But this perspective must be tempered with the inclusion of another metric that adds depth to the context in which LTV is evaluated: virality.

Virality and LTV

Virality – specifically, k-factor – changes the dynamic of the relationship between LTV and CPI: because virality represents cost-free growth, it reduces the effective price paid for each user in a marketing campaign. Taking the opposite approach – using k-factor to augment LTV – is inappropriate because LTV is specifically interpreted to describe the revenue contributions made by a single user.

Considering k-factor as an element which reduces a product’s CPI has the added benefit of preventing a line of thought from taking root wherein virality and paid user acquisition are considered mutually exclusive.

Highly-viral products can indeed benefit from user acquisition; in fact, they benefit to a greater degree than non-viral products, since a reduced eCPA hastens the point at which overall marketing revenue begins to decline with increased volume. In a sense, virality shifts the profitability curve of a marketing campaign up, increasing the number of users that can be acquired at each level of profitability.

LTV and sunk costs

It’s tempting to think about LTV as an overall revenue function for a particular product – and, in doing so, to dictate that LTV should compensate for the development costs incurred in bringing the product to market.

But this thought model ignores the fundamental role of LTV as a marketing metric. LTV should not, in fact, address development costs: LTV should be used only to determine the return on marginal user acquisition at a specific point in time is positive.

To abstract LTV from overall firm profit, it must be confined within the parameters of marketing operations: LTV > CPI is not a business strategy, it is a marketing mandate, and that mandate operates within budgetary limits. Because LTV is merely a long-term approximation of revenue, it can’t be matched to expenses on an ongoing basis.

The discrete payments that comprise the concept of LTV are revenue items, and those must be used to build forecasts and budget a firm’s operations month to month. Marketing spending should be framed within the boundaries of monthly revenue figures to allocate resources to a marketing budget in the way that best reaches growth targets given expected acquisition prices.

Although LTV can be reasonably estimated in freemium apps through the instrumentation of per-user level acquisition, marketing, as in every other industry, is conducted through budgets that optimize for growth while still addressing the other areas of the business.

In other words, marketing in mobile freemium is not an infinite feedback loop between LTV and CPI, ramping up so long as the spread is positive; rather, it is, as in traditional industries, one component of an operational mosaic that must contribute to a firm-level strategy.

Isolating LTV

Because LTV poses innumerable opportunities with which to be misinterpreted, misapplied, and misunderstood, using it outside of a marketing context — even if to describe the marketing process — is not productive. LTV is too broad of a metric to be helpful in a product development or management setting; rather, product managers should focus their efforts to optimize the metrics that describe user delight and engagement, such as retention and product-specific measures of activity.

The potential for misguided application of the LTV metric in product development runs deep. Most product managers, upon learning that the LTV of a product is too low to accommodate paid marketing, would likely react by implementing more aggressive monetization mechanics because these would be more immediately realized. But retention contributes as much to LTV as does monetization — and product changes instituted to focus on retention are less likely to result in “blowback” in the form of user alienation than are those focused on increased monetization.

LTV — as a probabilistic metric derived from multiple, disparate inputs — is not useful in describing anything other than the conditions under which marketing campaigns are evaluated. Using LTV as a business strategy, or to describe a firm’s general level of performance oversimplifies the dynamics of a business and obfuscates the real factors that contribute to its success. LTV is a complex concept, but its use is not: it determines whether or not marketing should be conducted.(source:ufert)

上一篇:独立游戏开发者如何自制美术内容

下一篇:分析电子游戏推崇僵尸元素的原因

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

闽公网安备35020302001549号

闽公网安备35020302001549号