探讨游戏对话质量的评判标准

作者:Richard Rabil

我们来说说游戏中的对话问题。尽管游戏如《荒野大镖客》、《辐射》系列和《质量效应》系列在剧情编写上有重大突破,但仍然存在许多死板、老套、泛滥的对话。例子简直随手可得。

(《Aralon HD》(iPad)最让人印象深刻的是它宏大的故事和丰富的场景。不幸的是,NPC和玩家的对话尽是陈词滥调。)

《暴雨》(2010)——一个失眠的女人:A hot shower! That’ll create the magic of sleep!(冲个热水澡!也许就能让我神奇地入睡了!)

《猎天使魔女》(2010)——Bayonetta(魔女): I’ve got a fever, and the only cure is more dead angels!(我发烧了,唯一的解药就是更多死掉的天使!)

《耻辱》(2009)——Zeke: Look, I’m being serious man, now DARPA is the mother-load of black-ops crap. If she’s in with those clowns, you better watch out, son.

Cole: Yeah, yeah, yeah, and Santa Claus shot J.F.K.

《阿尔龙:剑影》(iPad)(2010)——Elf: Leave me alone, please. Protagonist: Am I bothering you? Elf: Yes, as a matter of fact, you are. Now get lost. And don’t tell anyone you saw me here.(Elf:请你走开。主角:我打扰你了?Elf:是的,就是,现在就给我滚。不要告诉别人你在这里见过我。)

《生化危机4》(2005)——(钟声响起,想杀他的村民都离开后) Leon Kennedy: Where’s everyone going? Bingo?(人都哪去了?人呢?)

对于一个不需要借助交互式对话就能挣到百万美元的行业来说,这看起来似乎是小问题。为了成功,游戏首先必须成为游戏,这条黄金法则通常导致对话成为次要考虑,不过这也是合情合理的。

然而,当制作包含复杂的剧情的游戏时,游戏对话的重要性就变了,特别是对于RPG、具有复杂的活动的FPS(如《使命召唤:黑色行动》)和具有大量过场动画和剧情线的RTS游戏(如《星际争霸2》。无论如何,Darby McDevitt(《刺客信条:血统》的作者)认为,如果剧情是你的游戏的中心,那么你必须把编写看得与其他设计部分一样重要。为什么?因为在这些类型的游戏中,糟糕的对话可能“或多或少打断你的沉浸感”,导致你不断地意识到自己只是在屏幕前玩游戏的人。

“优秀的”游戏对话是怎么样的?

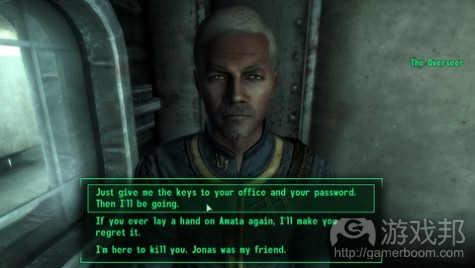

(理想地说,游戏对话支持游戏的交互性,例如《辐射3》中的分支对话。这是很难平衡的,因为涉及其他因素如辅助性、可信度和深度。)

好的对话,一方面可以增加玩家对角色和整个虚拟世界的认同感、深化他的情绪性沉浸感和增加游戏的重玩价值。不幸的是,我们找不可到可量化的证据。不过,我们可以找到一些对话例子,这些例子提高玩家的沉浸感水平,给他们留下深刻的印象。我们以Nathan Drake的台词为例。另外,我们可以从其他编写方面颇受好评的游戏中找到令人难忘的台词:

《龙腾世纪:起源》(2010)——Morrigan: “And now we have a dog. And Alistair is still the stupidest member of the party.”(现在我们有一只狗了。但Alistair仍然是我们当中最蠢的人。”

《荒野大镖客》(2010)——John Marston:(讥讽地)“I’m gonna give you a chance to kill me, ’cause I’m just that nice.” (抓住一名执法人员)“America! Home of the free!”(我赐予你杀我的机会,因为我是个好人。美国,是自由之国!)

《传送门》(2007)——GLaDOS: “You euthanized your faithful Companion Cube more quickly than any test subject on record. Congratulations.”(你让你忠实伙伴Cube安乐死的速度超过任何有记录的测试对象。恭喜。)

《Baldur’s Gate》(1998)——-主角: “Utterly amazing! You spoke so long, but you didn’t say anything.”(真是太神了!你讲了这么多话,却什么也没说出来。”)

这里的难题在于(特别是对于游戏作者和评论家而言),我们怎么知道什么才算是“高质量”的对话?有没有什么适用于所有游戏的标准?作为一名职业技术文写手、有抱负的游戏作家和RPG爱好者,这个问题也困扰了我一年半了。所以我看了许多书,玩了许多重剧情的故事(游戏邦注:如《质量效应》、《辐射3》、《龙腾世纪:起源》)。根据我玩游戏的经验和对这个话题的深入挖掘,我发现至少有四条标准是一直存在的:

1、辅助性:对话是否满足这条最低要求——给玩家提供其学习规则、得到提示或玩游戏必需的信息,但又不会表现得太明显?

2、可信度:角色说的话是否是真正的人会说的?

3、深度:角色以否以有意义的方式说台词?

4、游戏性/交互性:对话是否适当地支持游戏的交互性?

当然,这些标准可没有像看起来那么简单,因为大多还取决于其他相关因素如游戏类型、美术风格和目标受众等。还有一个表达问题:可能对话本身写得不错,但被糟糕的配音和劣质的音效拖了后腿。“游戏性/交互性”这条标准基本上完全取决于各款游戏的特征、类型惯例和技术难题。复杂的RPG的写手在写分支对话时面临的挑战不同于写无分支对话、比较线性的动作冒险游戏的写手。

我仍然不知道我们是否太讲究如何判断游戏对话的质量了,以及我们是否需要建立某些通用的分析标准。或者,至少让人可以更批判地讨论游戏对话和寻找游戏对话中“可行”或“不可行”的实例。

谢天谢地,这不是一个新领域。有些资料已经帮我把这个话题想得更深入了,比如Wendy Despain的《Writing for Video Game Genres》和Donald Freeman的《Creating Emotion in Games》,以及许多博文、学术期刊、BioWare和Bethesda Softworks(我最喜欢的两家游戏公司)的游戏作者的采访。但最重要的是,我发现挑选游戏的一部分(或几个相关的部分),玩到透,再从不同的角度分析,把它们放在游戏故事的大背景下,再结合自己的游戏经验加以思考,是很实用的做法。毕竟,单纯地阅读脚本或翻阅引文就评价游戏对话的优劣,是不公平的做法,分析游戏对话是需要经验的。那样我们才能批判地评价它是好是坏或介于不好不坏的灰色带。

结论

总之,即使我们得出普遍认同的标准,评价游戏对话仍然是一件含糊、主观的事。要考虑的因素太多了,并且很难准确地说出对话如何有利于提高游戏的整体沉浸感。最好是具体问题具体分析,也就是一次只专注于一款游戏,或一个部分,然后从那些玩过它的人当中收集足够多的数据和观点。(本文为游戏邦/gamerboom.com编译,拒绝任何不保留版权的转载,如需转载请联系:游戏邦)

The ups and (mostly) downs of game dialogue

BY Richard Rabil

The ups and (mostly) downs of game dialogue

Aralon HD for iPad is impressive in narrative scope and rich environments. Too bad neither the NPCs nor the dialogue get any more interesting than the cliché lines like this one.

Let’s face it. Despite the strides that games like Red Dead Redemption, the Fallout series, and the Mass Effect series have made in the realm of game writing, there is still a lot of stilted, stereotypical, and clichéd dialogue out there. We needn’t look far for examples.

Heavy Rain (2010). Woman with insomnia: A hot shower! That’ll create the magic of sleep!

Bayonetta (2010). Bayonetta: I’ve got a fever, and the only cure is more dead angels!

Infamous (2009). Zeke: Look, I’m being serious man, now DARPA is the mother-load of black-ops crap. If she’s in with those clowns, you better watch out, son. Cole: Yeah, yeah, yeah, and Santa Claus shot J.F.K.

Aralon: Sword and Shadow HD for iPad (2010). Elf: Leave me alone, please. Protagonist: Am I bothering you? Elf: Yes, as a matter of fact, you are. Now get lost. And don’t tell anyone you saw me here.

Resident Evil 4 (2005). [after villagers trying to kill him have all left at the sound of a bell] Leon Kennedy: Where’s everyone going? Bingo?

This might seem like a small issue in an industry that earns billions of dollars without much help from interactive dialogue. To succeed, games need to be games first, and this golden rule usually makes dialogue a secondary concern, and rightly so.

However, the standards for game dialogue change when producing games that weave intricate narrative into their design. This holds true primarily for role-playing games, but it could also apply to first-person shooters with complex campaigns like in Call of Duty: Black Ops, or real-time strategy games with substantial cut scenes and plot lines, like StarCraft II. At any rate, as Darby McDevitt (writer of Assassin’s Creed: Bloodline) has argued, if narrative is central to your game, then you must treat writing—and by extension, dialogue—as a vitally important design component. Why? Because in these types of games, bad dialogue can “more or less eject you straight out of the experience” and make you remember you’re just a player in front of a screen.

What counts as ‘good’ game dialogue?

Game dialogue will, ideally, support the interactivity of video games, as in this example of branching dialogue from Fallout 3. This is a tough act to balance in addition to other factors like helpfulness, believability, and depth.

Good dialogue, on the other hand, can strengthen a player’s identification with the characters and the overall virtual world, deepening her emotional engagement and heightening the game’s replay value. Unfortunately, we can’t find quantitative evidence of this. We can, however, point to examples of dialogue that have managed to make an impression on more than a few people in terms of a game’s level of engagement. For example, take this mash-up of Best Nathan Drake lines, which appeared in the Complex Video Game Voice-Over Awards in 2010. Furthermore, we can cite memorable lines from critically-acclaimed video games that have been recognized for excellent writing:

Dragon Age: Origins (2010). Morrigan: “And now we have a dog. And Alistair is still the stupidest member of the party.”

Red Dead Redemption (2010). [Various lines from John Marston.] (General taunt) “I’m gonna give you a chance to kill me, ’cause I’m just that nice.” (Lassoing a lawman) “America! Home of the free!”

Portal (2007). GLaDOS: “You euthanized your faithful Companion Cube more quickly than any test subject on record. Congratulations.”

Baldur’s Gate (1998): Protagonist: “Utterly amazing! You spoke so long, but you didn’t say anything.”

The difficult question, especially for game writers but also for critics, is how do we know what counts as “high quality” dialogue? Are there criteria we might apply across all video games? As a technical writer by trade, a game writer by aspiration, and a lover of RPGs, that’s a question that has nagged at me for the past year and half. So I looked into numerous books and played a lot of story-driven games, such as Mass Effect, Fallout 3, and Dragon Age: Origins. As I dug into the topic and reflected on my gaming experiences, at least four criteria kept emerging again and again:

Helpfulness: Does the dialogue meet the minimum requirement to give the player the information he or she needs to learn the rules, obtain a hint, or play the game, while not making things too obvious?

Believability: Are the characters saying things that a real human or sentient being would say?

Depth: Are the characters in the game saying their lines in interesting ways?

“Gameness”/“Interactivity”: Does the dialogue appropriately support the interactive medium of games?

Of course, these criteria are not as straightforward as they sound. Most if not all of them depend on interrelated factors such as genre, visual style, and intended audience. There is also the matter of delivery: the dialogue itself might be well written, but it could be easily hindered by poor voice acting and subpar visual effects. And the “gameness” / “interactivity” criterion is almost entirely dependent on each game’s unique characteristics, generic conventions, and technical challenges. Writers of branching dialogue in complex RPGs will have different challenges than those who are writing non-branching dialogue in relatively linear action-adventure games.

Still, I couldn’t get past the thought that if we are to seriously consider how to judge the quality of game dialogue, that we should try to establish some common analytical criteria. Or, at the very least, to get people talking about game dialogue more critically and examining instances of game dialogue that “work” or “don’t work.”

Thankfully, this isn’t new territory. Some sources that have helped me think more deeply about this topic include Wendy Despain’s Writing for Video Game Genres, Donald Freeman’s Creating Emotion in Games, a variety of blogs and academic journals, and even interviews with game writers at BioWare and Bethesda Softworks (my two favorite game companies). Most of all, though, I’ve found it helpful to pick a specific segment of gameplay (or several related segments), play them through, and analyze then from different angles—taking care, of course, to consider them in the broader context of the game’s narrative and my experience with it as a whole. After all, it’s unfair to make judgments about game dialogue by simply reading scripts or reading over memorable quotes. Game dialogue must be “experienced.” Only then can we start to critically examine whether it is good, bad, or somewhere in the gray area in between.

Conclusion: What’s next?

In sum, even if we gained widespread agreement on the criteria for evaluating game dialogue, it would remain a messy, subjective business. There are a lot of factors to account for, and it’s hard to agree upon the precise ways in which dialogue will benefit the overall immersive effect of a game. Ideally, we could focus on one game at a time, or perhaps one segment at a time, and get data and opinions from a large number of people who have experienced it.

That’s why I started Dialoguejunkie.com, where I post videos of game dialogue and ask visitors to rate and/or comment on them. This will, I hope, foster a more community-oriented sense of what works and what doesn’t in game dialogue, and ultimately promote better writing in the industry.(source:gamesauce)

闽公网安备35020302001549号

闽公网安备35020302001549号