阐述游戏设计经验之常见游戏元素(四)

作者:Sharon Bollergame

在一篇文章中,我介绍了游戏机制——引导玩家和规定游戏如何反应玩家行为的规则和流程。这次,我将继续介绍游戏元素。(请点击此处阅读本系列第一、第二、第三篇)

所有游戏都有持续吸引玩家的“元素”。有些游戏有很多元素,有些游戏则很少。游戏中应该包含什么元素,这是一个应该仔细考虑的问题。对于学习类游戏,常见的元素有如下12种:

注:因为元素太多了,本文只重点介绍前5种;其他几种将放到下一篇文章中继续介绍。

冲突

为了让游戏有趣,必须有一些冲突。冲突可以有多种形式,但总是表现为玩家必须克服的挑战。挑战可以是物理障碍,也可以对抗其他玩家,或者是必须解决的谜题。

当你的学习类游戏具有冲突作为元素时,你应该思考:

1、根据我希望让玩家学习的东西,什么冲突最合适?冲突应该产生于与其他玩家的竞争还是所有玩家合作克服的挑战?或者,冲突是否可以是对抗游戏本身的某种挑战?例如:益智游戏中的冲突其实就是你解决益智题的挑战。

2、如何表现我想让人们处理的现实世界的冲突?例如:质量和时间或质量和预算之间的矛盾。

3、为了模拟现实世界的冲突/挑战,我需要什么样的游戏机制?

合作和/或竞争

对于学习类游戏,以合作为元素通常比纯竞争更好。与其他玩家的直接竞争可能导致玩家失去动力或产生消极反应。相反地,玩家合作克服游戏挑战往往能激励玩家和培养团队精神。合作让玩家们共同努力,竞争让玩家们互相对抗。只有一个玩家或一支队伍获胜,意味着其他人都输了。玩家的关注焦点会因为你采用的元素或结合元素的方法而发生变化。竞争也是可以使用的元素,但你必须考虑到它可能产生的结果。

当设计学习类游戏时,你要问你自己:

1、玩家必须在现实生活中竞争吗?竞争与使用我想让玩家学习的技能或知识无关吧?

2、如果竞争是现实生活内容的一部分,那么我可以把它与游戏结合起来让玩家合作打败游戏或让玩家在游戏中互相竞争吗?

3、竞争会激励目标玩家还是使他们沮丧?如果只有一个玩家赢而其他玩家都输,会产什么什么样的消极后果?我如何安抚这些情绪?

策略和运气

在策略游戏中,玩家控制权表现为玩家决定,这些决定会影响游戏玩法或玩家达到目标的可能性。相反地,在强调运气的游戏中,玩家几乎无法控制结果。

游戏可以只有策略元素或只有运气元素,也可以二者兼有,或偏重于其中一种。赌博游戏基本上是靠运气的。有策略或运气元素的游戏比没有策略或运气的游戏更有趣。

当设计学习类游戏时,你要问你自己:

1、游戏是否无意中造成一种基本上靠运气或一系列事件顺序就能达到成功的局面?(这比你想象中的要容易发生。我们最近玩了一款桌面游戏,玩了几次以后,我们发策首先占上风的玩家获胜的机会比占下风的玩家高得多。)

2、我可以把策略和运气混合起来,做成一种我希望玩家学习的技能或一种列家必须应用这种技能的情境吗?

3、在现实世界的决定中,玩家有什么控制权?我如何在设计游戏时运用它?

案例

例1:我们设计了一款辅导游戏。游戏中的跨国公司希望把产品开发和发行时间从10-12年减少到8-10年。他们认为辅导是减少这些时间的方法之一。但我们也知道,有时候超出人的控制之外的因素会影响开发时间……所以我们把运气当作一种元素放进游戏中。当玩家登录面板的特定空间时,他们抽出一张“生命开始”卡片,这张卡片会积极或消极地影响他们的时间表。策略不起作用。这些卡片模拟诸如经济衰退、公司雇用冻结、预算损失等现象。

例2:我设计了一款游戏,它模拟保持公司职业道德同时处理联邦机构的临时要求变更的压力。基本上,如果玩家计划做得不好,就会导致在机制前来调查时没有时间测试他们的产品。许多玩家表示有执行测试。这款游戏模拟了现实世界的问题,而我的策略元素就是为了支持这种玩法而设计的。

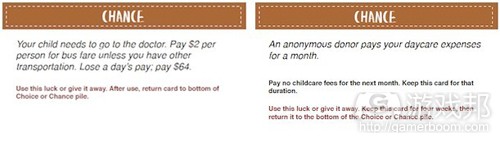

例3:以下卡片出自《A Paycheck Away》。它们玩家每回合都必须抽的运气卡。这款游戏模拟了现实世界的问题—-可能发生但玩家无法控制的好事和坏事。

(本文为游戏邦/gamerboom.com编译,拒绝任何不保留版权的转载,如需转载请联系:游戏邦)

Learning Game Design Series, Part 4: Game Elements

by Sharon Bollergame

Welcome to Part 4 of my multi-part Learning Game Design series. In my last post, I talked about game mechanics. These are are the rules and procedures that guide the player and the game response to the player’s moves or actions. Now we’ll move on to game elements.

Every game has “elements” or features that keep people engaged. Some games have a lot; others have very few. The choice of what to include should be deliberate. With learning games, you should consider how each element supports the learning process. There are many game elements you can include; this graphic shows 12 common ones:

Note: Because there are so many, this post focuses only on the first five. I’ll be covering the others in my next posts.

Conflict

For a game to be interesting, there needs to be some sort of conflict. Conflict comes in many forms, but it always represents a challenge for the player to overcome. The challenge could be physical obstacles, it could be combat with another player, or it could be a puzzle that has to be solved.

Things to ask yourself about incorporating conflict as an element in your learning game design:

Given what I want people to learn, what conflict is most appropriate? Should I incorporate a conflict that arises with other players or should I incorporate challenges that all players work together to overcome? Or should I include some sort of challenge against the game itself? Example: puzzle-style games are really a challenge that pits you against the puzzle.

How can I best represent the real-world conflicts I want people to deal with? Example: conflict between quality and time constraints or quality and budget.

What game mechanics can I create to simulate the real-world conflicts/challenges players encounter?

Cooperation and/or competition

With learning games, cooperation is often a better element to use than competition alone. Direct competition with other players can demotivate learners or set up a negative dynamic. In contrast, cooperation between players to overcome a game challenge can often motivate players and foster teamwork. Cooperation gets people working together; competition pits people against one another. Only one person or team wins—while everyone else loses. The players’ focus is very different depending on which element you employ or how you combine the two elements together. Competition can be appropriate, but you need to consider the outcomes it can produce.

Questions to ask yourself when designing a learning game:

Do my players need to compete in the real-world or is competition not a factor in using the skill or knowledge I want people to learn?

If competition is part of the real-world context, do I incorporate it into the game as players working together to beat the game or as players competing against each other within the game?

Will competition motivate or demotivate the target group I’m designing the game for? What negative consequences might occur if only one person wins and everyone else loses, and how do I manage those emotions?

Strategy and chance

Strategy puts control into the players’ realm in the form of decisions they can make that affect gameplay or their odds of achieving the goal. On the other hand, games that are heavily based on chance put the player in a highly reactive mode, one where they have little control over the outcome.

A game can have neither strategy or chance, it can combine both, or it can only focus on one. Gambling games are largely games of chance. Games with little or no strategy or chance built in can be less interesting to play than those that use these elements.

Questions to ask yourself when designing a learning game:

Is my game unintentionally creating win states that are largely achieved by chance or a specific sequence of events? (This can happen more easily than you think. We recently played a board game where it became clear over several game plays that the person who got to go first—which was determined by age—had a much greater chance of winning than the person who went last.)

Do I blend strategy and chance in a way that mirrors the skill I want my player to learn, or the context in which they will have to apply the skill?

What control do players have in the real-world over decisions? How do I design that into the game?

Case in Point

Example: We devised a coaching game for a global company that wanted to reduce its product development and launch timeframe from 10-12 years to 8 to 10 years. They felt coaching was one means of reducing this timeline. We also knew, though, that sometimes factors outside someone’s control would affect the development timeline… so we included chance as an element. When players landed on specific spaces on the board, they drew a “Life Happens” type of card that either positively or negatively influenced their timeline. Strategy played no part in the effect. These cards simulated things such as an economic downturn, a hiring freeze within the company, a loss of budget dollars, etc.

Example: I designed a game to simulate the pressures of maintaining the company value of ethics and honesty while dealing with last-minute requirement changes from a federal agency. In essence, if players hadn’t planned well, they ended up not having enough time to test their products before the regulatory agency arrived to inspect things. Many players signed forms in the game indicating that tests had been performed. The game mimicked a real-world issue, and my strategy elements were designed to support this.

Example: The cards below are from A Paycheck Away. They are chance cards that players have to draw on each turn. These simulate real-world things—good and bad—that can happen but which the player has no real control over.(source:theknowlegeguru)

闽公网安备35020302001549号

闽公网安备35020302001549号