解析引导玩家理解游戏交互性的6个层次

作者:Jainan Sankalia

这个模型从一个有趣的角度来说,解释的就是玩家在体验一款明显“由设计师操纵”的游戏时所能够掌握的理解层次。这个模型的每个层次都是基于交互性如何呈现在玩家面前,以及玩家如何在体验游戏过程中运用这种交互性。

开发者可利用这一模型来创造自己的游戏体验。通过观察交互性视角,解析它如何改变游戏所传递的知识,就可以更清楚地发现不同层次的交互性如何引导玩家对游戏的认知和理解。

展示美学元素

展示美学元素代表游戏通过视听内容向玩家呈现的感觉信息。这是该模型的核心层次,因为这是玩家最先接触到的体验。

这一层次还代表着交互性呈现给玩家的方式。通常玩家输入的反馈是通过视觉信息输出。这包括视觉信息的形状和风格,环境声效以及乐曲,文本和语音内容——这些信息都能够传达体验元素。

即使是抽象的桌游,例如象棋也会根据棋子的形状和名称来传达中世纪战争元素。骑士、主教的形状可传达他们的行为方式。黑白棋子则可呈现双方玩家的明显区别。甚到是棋子的实体纹理也能透露历史信息。通过美学元素呈现的信息可以传达游戏趣味本质的元素,而这些元素又可用于指导玩家。

例如,这是多数问答游戏用于引导玩家的层次。为了成功学到问答游戏所传授的知识,玩家只需要了解问题,他们的回答一般都会以文字形式呈现。《Trivial Pursuit》就是一个知识测试,在桌面上移动棋子并不会教你关于地理、科学或自然分类。桌面和棋子存在的原因,部分只是为了打破阅读所有问题和答案卡片的单调感。

通过观察所有方法,找出向玩家呈现哪种感应输入,开发者可以利用特定方法向玩家传授特定知识。桌游《Twilight Struggle》使用了介于1945–1989年这一历史时期作为故事背景,并用美国和前苏联代表两名玩家,让他们争夺该时期的世界霸权,控制不同的国家/地区。

游戏中每张卡片都有一张历史照片。该照片与游戏机制无关,也并非玩游戏的须知事项,但却传达了另一种冷战背景信息。这一信息也并不会帮助玩家完成游戏,但确实提供了一种与该历史时期相关的教育性知识。该游戏桌面所使用的国家边界也向玩家传递了一种地理知识。

从一个更有趣的角度来看,每个国家的稳定数值代表该国相对意识形态的稳定性,独立性及力量。《Twilight Struggle》通过一系列视觉内容,向玩家传递了大量历史信息。

但卡片和桌面的形状都是标准的矩形。这种形状可以提供额外信息,但却有可能影响整体游戏体验。此外,实体纹理以及光滑的卡片触感却并不能反映历史背景。当然,这要取决于游戏开发者想使用哪些方法来传达信息。关键在于评估游戏呈现美学元素的所有潜在选项是否能够承载这一玩家理解层次的信息。

机制

机制增加了交互性。一个机制是指引发一个输出反馈(游戏邦注:介于玩家和系统之间,或者完全在系统间)的单个输入实例。要理解该输入将为玩家产生什么反馈信息。能够从根本上影响到游戏的是第一个层次,它将交互性与反馈整合到玩家对有趣体验的理解中。在这个基础上,玩家了解了输入和输出规则。他们掌握之后,可能就会开始疑问为何特定的输入会产生特定的输出。回答这一问题可以让玩家掌握特定的逻辑。

关于机制的一个简单典型就是射击游戏中的爆头。在许多射击游戏中,爆头比身体其他部位中弹的伤害更大。玩家也知道头部被击中远比身体中弹更糟糕。当然,比起现实生活的情景,这并非最准确的理解,但每个机制都在向玩家传递该游戏空间的规则。这些游戏规则可用于向玩家传授开发者希望他们去了解的现实逻辑或游戏逻辑。

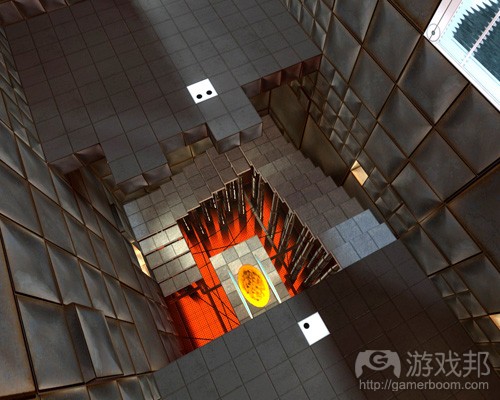

许多谜题游戏,例如《传送门》,就在逐渐向玩家引进新想法和理念。Test Chamber 10就向玩家传授关于动量守恒定律的游戏机制。通过探索这一理念,玩家就可以学到游戏内在逻辑的额外信息。

开发者也可借助这种探索和发现游戏内在逻辑的理念传递特定知识,例如牛顿物理学(玩家在之后将通过另一机制证实这一知识)。在之后的试验室中,玩家必须使用一个加重的立方体的重力,正如他们之前看到自己被保留在传送门之间的动量。

系统

系统代表某个特定框架,以及游戏中不同规则之间内部反馈的所有可能的输入和输出。系统同不同机制组成,为游戏的仿真性提供一种逻辑感。了解系统中所有可能的交互性,可以传达该系统运行的基础元素。如果规则系统采用了准确的表述,或者游戏模拟了现实,那么该系统知识就会传递现实逻辑。玩家了解更多某个系统中的机制,就会开发出一个关于所有机制如何相互关连的框架。

这种机制间的相互关联是系统对于如何解决问题的思考方法的一个中心元素。观察某个输入形成的大量和长期反馈,可以创造一种对于游戏可能呈现哪种复杂问题的感应能力。这里的系统指的是任何机制的组合。区别并不在于游戏的整个系统及其不同的子系统。这一层次关注的是不同输入和输出在游戏内部的相互关系。这可能会受到玩家在系统中的输入,以及基于游戏内在规则的反馈的影响。

在《Lunar Landr》这款游戏中,推力和重力的关系变化取决于玩家选择的是地球、月亮还是木星。理解了玩家输入的推力如何改变着陆器(基于星际对象的输入选择)的输出结果,玩家就会理解月球上的重力弱于地球,而后者重力又弱于木星这一理念。

通过对交互性之间关系的理解,玩家也许自己就能得出结果,加强自己对游戏体验的理解。

像《模拟城市》、《Microsoft Flight Simulator》等高度基于模拟内容的游戏就致力于系统层面,为玩家创造复杂的情况。拥有主导游戏状态的内部生态系统的游戏也会有一些内部机制(游戏邦注:这些机制会根据它们与其他机制的关系产生一系列可能的内部结果)。

许多开发者喜欢利用Tadhg Kelly的“游戏制作和设计的5个视角”来制作趋于无限可能的复杂交互集合。当玩家发现这些可能性,并决定为何在该系统会发生这种可能性时,他们就开始在系统层面进行操作了。

Daniel Aronson曾以庄稼虫害为例强调了系统思维的重要性,他指出使用一种针对害虫A的杀虫剂将在短期内减少庄稼的损害,但从长期来看却会增加对庄稼的危害。这是一种针对特定昆虫的意外输入导致另一种昆虫数量下降的结果。

在这个系统中存在许多机制,包括昆虫A对庄稼的反馈,昆虫B对庄稼的反馈,以及昆虫A对昆虫B的反馈。将这个案例运用到这一模型上,开发者了解所有的这些机制,就可以让玩家最大化地认识问题所在,以及调整系统层面每个群体,以及每个机制更改游戏状态时所产生的潜在长期后果。

战术

战术是玩家为实现某种输出结果,在了解其他可能的输入方式后,选择了某一特定输入方式。通过了解当前的游戏现状和系统,以及不同输入将如何改变当前游戏状态,玩家就可以制定计划,并立即采取措施根据自己选择的输入方式更改这一状态。

要让玩家获得一种选择感,不一定需要令其了解整个系统,但至少要了解两种可能的输入方式。执行这种选择就属于一种战术。对于玩家而言,了解战略选项正是他们开始获得代理感的关键点,因为他们了解个系统的交互关系时就可以发现有意义的选择。这里所指的玩家代理是“玩家能够采取有意义的行为,并在游戏中看到可视结果的能力”。

桌游《Pandemic》就是一个让玩家制定战术决定的优秀典型。轮到每个玩家时,他们一次都只能采取4步操作。通常游戏状态极为反复无常,玩家在一开始就得应对诸多短期问题。玩家需要即时做出选择,以便对付当前游戏状态中存在问题的城市,及时改变游戏形势。

由于这种游戏粘性就来自代理感,这一层次就成为玩家需要理解的重要层次。分析开发者自己游戏中的这个层次,有助于开发者通过确定玩家可能做出哪种战略选择而利用这一粘性。开发者可以在每个时刻决定玩家将面临哪些有意义的选择,以及如何更好地向玩家反馈这些短期决定。

战略

当玩家得到代理感,并且在制定短期战术性决策时,他们就会开始制定一系列战术(或输入),从而影响游戏的长期状态,这就是战略。战略可以从交互层面抽象出来,是玩家开始理论化如何基于一系列交互性改变游戏未来状态的节点。玩家会预测他们的一系列战术除了每次输入以及其他因素(游戏邦注:例如其他玩家的输入)的即时反馈之外还将如何改变游戏状态,如何通过一次输入干预即时而直接的反馈。

这里我们再次以《Twilight Struggle》为例,该游戏使用战略传达了围绕冷战时期的意图和冲突。例如,游戏将根据玩家在非洲国家所获得的力量记分时,双方玩家都会着手计划改变自己在该地区的影响力。当游戏开始时,玩家双方在这些国家都没有什么影响力。有一个典型战略就是利用低稳定数值在一个南部国家推行政变的即时战术,而该国恰好在地沿上接近于其他易受影响的国家。这样,玩家在未来就可以逐渐向北扩散自己的势力范围。

当然,发动政变的戒备状态会令游戏接近于核战结束的状态。或者,玩家也可以选择在中东地区获得足够的控制权,以便向南部灵活扩散。

无论是哪种情节,玩家都要策划好自己将要执行的操作,以便获得尼日利亚、扎伊尔、安哥拉等极大影响游戏得分的关键战场的控制权。这些战略会随着敌手的控制变化而变化。

这些变化迫使玩家采取新的即时战术操作,以便实现长期的战略目标,而这些目标则可通过操作的美学隐喻告知玩家,美苏两大势力在此期间的潜在思考过程以及行动意图。

系统所提供的即时反馈是一个将战略从之前的层次——战术区别出来的中心元素。了解玩家执行短期目标和策划长期目标时的发现,便于开发者提供极为不同的信息。

正如输入系统是由多个机制组成,决策战略也是由多个战术构成。虽然它们在制定有意义的决策方面存在相似之处,但绝对不可混淆战略和战术的概念,因为玩家在这两个层次所需投入的思考过程并不相同。玩家所推理的即时影响和最终影响都是开发者为其提供独特体验和知识的机会。

情境

游戏空间之外的信息也会影响玩家对游戏状态如何变化的理解。这种外部知识就是与游戏相关的情境。这种情境可以是玩家根据之前同个系列游戏的理解层次,或者对类似游戏的理解所认定的知识。

这种情境化的知识也同样适用于玩家对其他玩家在其他游戏,或同款游戏其他事件中行为的理解。了解人类心理可以让开发者知道玩家如何在特定游戏中部署战略。Katie Salen和Eric Zimmerman将游戏空间描述为“魔法圈”。这个魔法圈之外的信息创造了一个认知框架。而“认知框架又创造了理解和影响我们认清事物的情境”,例如游戏状态。

这里以之前提到的射击游戏中的爆头为例,玩家对其他射击游戏中同个机制的了解,会导致玩家认为这一机制也适用于当前游戏。这里的情境就会影响到交互性的机制层次,因为它是通过呈现美学元素来传达信息。整个游戏空间以及所有之前的玩家理解层次,可能都会受到玩家所带来的外部信息的影响。在之前游戏中发挥作用的战术可能会让玩家觉得,同个策略在续集游戏中也会产生相似的结果(除此有人事先告知这样并不可行)。

关于使用外部信息来影响玩家抉择的一个典型,就是与石子剪子布这种简单游戏有关的心理元素。在World Rock Paper Scissors Society页面有这样的描述,“要知道总有一些能够激励对手的动作。你可以使用一些伎俩和技巧来打破这种平衡。”这些伎俩和技巧包括在游戏开始前进行一次冒险,魔法圈之外是能够影响战略选择的游戏空间外部的情境信息元素。

网络系列文章Extra Credits则讨论了《英雄联盟》中的周期性失衡的理念。这一理念解释了玩家如何根据自己对付一般战士的实力来选择特定战士,这导致许多玩家去选择特定战士。而这个战士的弱点则可能被选择了另一种特定战士的玩家所利用。了解亚策略的当前发展状态,可以让玩家获得如何调整战略的情境化知识。

玩家开发的这种意识对开发者构成了挑战,因为玩家可能掌握了那些情境化知识。从制作教程的复杂性,通关攻略对经典冒险游戏的影响,以及游戏对新玩家的易用性,这一切均受到玩家可能掌握的情境化知识的影响。涉及这个模型的其他层次,这种挑战就更加复杂了,因为每个层次都会受到这种情境化知识的影响,而这又会改变玩家对原先知识的理解方式。

总结

开发者认识到玩家可能从中获得知识的这些层次,就有可能据此在不同时间为其打造特定的体验以传达特定的信息。开发者可通过结合每个层次为玩家提供知识的方式,创造一种更为引人入胜或富有教育性的体验。

针对每个拥有输出反馈的输入交互,每个层次都会为玩家提供独特的学习机会。而作为核心层次的展示性美学元素则描述了交互性如何向玩家传递信息。下一个层次,机制则是一个交互性实例。系统是所有可能的交互。战术则是制定单个交互的选择,战略是策划交互的多个选择,最后一个层次,情境则是使用外部信息来影响玩家对这些交互的理解和用途。(本文为游戏邦/gamerboom.com编译,拒绝任何不保留版权的转载,如需转载请联系:游戏邦)

Layers of Player Understanding

by Jainan Sankalia

This model explains, from a ludic perspective, the layers of understanding a player can obtain experiencing a heavily designer-authored game. Each layer of this model is based on interaction and how interaction is presented to the player and utilized by the player as they engage with the experience.

This model aims to be a tool for developers to use in crafting their experiences. By looking through the lens of interaction and breaking down how that changes the knowledge a game communicates, a clearer picture emerges about how interaction at its different layers guides the player’s learning and understanding of the game.

Presentation Aesthetic

Presentation Aesthetic represents the sensory information revealed to the player usually expressed through the audiovisuals. This is the core layer for this model, as it is the first exposure the player has to the experience.

This layer also represents how interaction is presented to the player. Often the feedback from an input by the player is outputted by the system via audiovisual information. This is not limited to, but includes the shapes and styles of the visuals, the ambient sounds and musical score, and the written and spoken text — these all communicate elements of the experience.

Even abstracted board games such as chess communicate elements of medieval warfare based on the shape and names of the pieces. The shape of a knight compared to a bishop may communicate aspects of their behavior. The black and white pieces denote a clear distinction between the two players. Even the physical texture of the pieces could reveal historical information. The information presented through the aesthetic can communicate elements of the ludic nature of the game that can be utilized to teach the player.

As an example, this is the layer that most trivia games operate on to educate the player. To successfully learn what the trivia game is trying to teach only requires the player to have knowledge of the questions and their answers usually presented as text. Trivial Pursuit is a test of knowledge; moving around the board using the pieces does not teach the player about the categories of geography, science, or nature. The board and the pieces are there, at least in part, to break the monotony of reading all the question and answer cards.

By observing all the methods by which sensory input is presented to the player, developers can utilize each method for a specific lesson to be taught. The board game Twilight Struggle uses the historical time period between 1945 and 1989 as a backdrop for two players, representing the U.S.A. and the USSR, to compete for influence and control over the various countries and regions of the world.

A historical photo accompanies each card in the game. This photo is not related to the mechanics, nor is it required in order to play the game, but it does provide another avenue of communication about the historical Cold War setting the game takes place during. The turn counter equates to the years between 1945 and 1989 represented by a picture of the leader that was in office during that year. Again, this knowledge does not aid the player towards completing the game, but it does afford an educational knowledge about the time period. The historically accurate map of the world including country borders used by the game’s board conveys a geographic knowledge the players may learn from.

From a more ludic perspective, the values of each country’s stability number reveal each country’s relative ideological government stability, independence, and power. Twilight Struggle does a great job of conveying a variety of historical information by exposing the players to a variety of visual information as they play the game.

However, the shape of the cards and board are a standard rectangle. This shape could have been another opportunity to impart additional information at the potential detriment to the overall experience. Also, the physical texture and feel of the smooth cards don’t contribute to the historical setting. Of course, it is up to the developers of the game to determine which of the many methods they wish to utilize for communication. The key is evaluating all the potential options the game’s presentation aesthetic affords information at this layer of player understanding.

Mechanic

Moving beyond the presentation aesthetic, Mechanic adds interaction. A mechanic is a single instance of an input that causes an output feedback either between the player and the system or entirely within the system. Understanding what and why that input has that specific feedback yields knowledge for the player. This ability to affect the game in a fundamental way is the first layer that incorporates interaction and feedback into a player’s understanding of the ludic experience. At its base, the player learns what the rule for the input and output are. Once learned, the player may begin to question why a particular input has that particular output. Answering that question suggests a certain logic for the player to grasp.

A simple example of a mechanic is a headshot in a shooter. In many shooters, a headshot deals more damage to the target than a body shot. The player learns that being shot in the head is worse than being shot in the body. Of course, that is not the most accurate interpretation compared to a real life scenario, but every mechanic informs the player about the rules of the game space. These rules taught in the game space can be used to teach certain rules the developer may want to educate the player about whether about real life logic or game logic.

Many puzzle games, such as Portal, slowly introduce new ideas and concepts to the player. Test Chamber 10 of the game teaches the player about the game’s mechanic for conservation of momentum. By exploring and discovering this concept, the player is afforded additional information about the game’s internal logic.

That same notion of exploring and discovering the game’s internal logic may be utilized by a developer intending a certain knowledge, such as Newtonian physics, be taught to the player that may be tested later by another mechanic. In later test chambers, the player must use a weighted cube’s momentum just as the player observed his or her own momentum being conserved between portals.

System

A System represents all possible inputs and outputs within a given construct as well as all the internal feedbacks between various rules within the game. Made up of various Mechanics, a System provides a sense of logic to the game’s simulation. Understanding all the possible interactions within the system communicates the fundaments of how that system operates. If the system of rules is an accurate representation, or simulation, of the reality being addressed by the game, then the knowledge of the system conveys the logic of that reality. As a player learns more mechanics within a given system, the player develops a framework for how all the mechanics interrelate.

This interrelation between mechanics is a central component of the system’s thinking approach to problem solving. Observing the multiple and long-term feedbacks from a given input create awareness towards complex problems the game may present. System here refers to any group of Mechanics. A distinction is not made between a game’s overall system and its various sub-systems. This layer focuses on the inter-relationship between different inputs and outputs internally within the game. These may be affected by the player’s inputs on the system, but are also feedbacks within the game itself based on its internal set of rules.

In the game Lunar Lander, the relationship between thrust and gravity changes depending on if the player chooses Earth, the Moon, or Jupiter. Understanding how the thrust input by the player changes the output of the Lander based on the choice input of interstellar object, the player grasps the idea that gravity on the Moon is weaker than on Earth which is weaker than on Jupiter.

Through understanding the connection between interactions, the player may draw associative conclusions enriching their understanding of the experience.

Heavily simulation-based games such as SimCity or Microsoft Flight Simulator focus on this to create complex situations for the player. Games with an internal ecosystem that governs the state of the game have internal mechanics that yield a number of possible internal results based off their relation with other mechanics.

Many developers that fall under Tadhg Kelly’s simulationism lens of game making create complex sets of interactions that lead to near infinite possibilities. As the player discovers these possibilities and determines why a possibility occurred in the system, the player starts operating on the System layer.

In terms of system thinking, the importance is outlined in Daniel Aronson’s example of crop damage by insects. He explains how the immediate feedback of using a pesticide on a particular Insect A in the short-term decreased crop damage, but in the long-term the crop damage increased. This was the result of an unforeseen input of that particular insect keeping another insect’s population down.

In this example system, there are many mechanics at work including Insect A’s feedback on the crops, Insect B’s feedback on the crops, and Insect A’s feedback on Insect B. In this example applied to this model, learning all these mechanics help the player understand the problem at large and potential long-term consequences of adjusting each population at the System layer as each mechanic alters the state of the game.

Tactic

Tactic is the player acting on the system by choosing a specific input after understanding other possible inputs in order to achieve a desired output. By understanding the current state of the game and understanding the system and how each different input will alter the current state of the game, the player can plan and take an immediate action to alter that state based on which input they choose.

Knowledge of the entire system is not needed, but knowledge of at least two possible inputs is needed to provide a sense of choice. Acting on this choice is a Tactic. For a player, understanding

the tactical options are the point at which players begin to feel a sense of agency because they are presented with meaningful choices they have become aware of by understanding the interrelations within the system. Player agency here “is the provision of capability for a player to act meaningfully and with visible effect in a game,” as described in this piece.

The board game Pandemic is a good example of the player making tactical decisions. On a player’s turn they are able to perform only four actions. Usually the state of the game is so volatile that the player must deal with the short term problems presented at the start of their turn. Because of the way the outbreak deck places previously drawn locations back on top of the deck, the player is aware of what problem cities have a high potential of being drawn at the end of their turn. As a result the player makes immediate choices to deal with the specific problem cities in the current state of the game, changing the game state in an immediately apparent way.

Because of the engagement that comes from a sense of agency, this layer of interaction is an important layer for the player to understand. Analyzing what this layer teaches in a developer’s own game provides an opportunity for the developer to capitalize on this engagement by determining what the tactical choices the player can make are at any given moment. On a moment-to-moment basis, a developer could determine what meaningful choices are presented to the player and how best to communicate the feedback of those decisions on the game state back to the player in the short-term.

Strategy

Once the player has a feeling of agency and is making tactical short-term decisions, the player begins to plan a series of tactics, or inputs, affecting the long-term state of the game, which is Strategy. Abstracting away from the acting aspect of interaction, Strategy is the point at which the player begins to theorize how to change future states of the game based on a series of interactions. The player makes predictions about how their sequence of tactics will alter the state of the game beyond the immediate feedback from each input as other factors, such as inputs from other players, interfere with the immediate and direct feedback from an input.

Using Twilight Struggle again as an example, the game uses strategy to communicate the intentions and tensions surrounding the Cold War. For example, knowing that in the future the game will score the balance of power in African countries, both players will plan on how to alter the influence in that area. When the game begins, neither player has any influence in those countries. An example strategy is using the immediate tactic of performing a coup in a southern country with a low stability number that is geopolitically connected to other easy-to-influence countries on the game board. By doing so, in the future the player may slowly spread their influence north.

Of course, by performing a coup the immediate feedback of the DEFCON level lowers putting the game close to the Nuclear War end state. Alternatively, the player may also choose instead to claim enough control over the Middle East to have the flexibility to spread influence south.

In either scenario the player is planning which course of actions to take in order to control the key battleground states in the area such as Nigeria, Zaire, and Angola that greatly affect the game’s scoring. These strategies are altered as opponents also attempt to control these areas.

These alterations force the player to take new immediate tactical actions in order to achieve a long-term strategic goal that via the aesthetic metaphor for the action informs about the potential thought process and intentions of the behaviors taken by the U.S.A. and USSR during this time period.

The immediacy of the feedback provided by a system is a central component that separates Strategy from the previous layer, Tactic. Realizing what the player discovers by acting on short-term goals compared to planning long-term goals provides distinctly different sets of information a developer could teach.

Just as a System of inputs comprises multiple Mechanics, a Strategy of decisions comprises multiple Tactics. Although similar in terms of meaningful decision making, this distinction between

Strategy and Tactic is important because of the difference in thought process a player engages in while operating at these two layers. Both the immediate impact and eventual impact a player

theorizes are opportunities for a developer to provide distinct experiences and knowledge.

Context

Information outside of the game space may also influence a player’s understanding of how the state of the game will change. This external knowledge is the Context surrounding the game. This context could be knowledge assumed by the player based on layers of understanding from a previous game in the same franchise or from understanding a similar game.

This contextual knowledge may also apply to the player’s understanding of other players’ behavior in other games or other instances of the same game. Even understanding human psychology can inform the player on how to strategize within a certain game. Katie Salen and Eric Zimmerman describe the game space as “the magic circle.” Information outside of the boundaries of this magic circle creates a cognitive frame. “Cognitive frames create contexts for interpretation and affect how we make sense of things,” such as the state of the game.

Using the prior example of headshots in a shooter, being familiar with this mechanic in other shooters will influence the player in assuming that mechanic applies to the current game as well. Here the context affects the Mechanic layer of interaction as it is communicated via the Presentation Aesthetics. The entire game space and all prior layers of player understanding may be impacted by the external information the player brings. A tactic that was useful in a previous game encourages the player to assume that same tactic will yield a similar result in the sequel unless the player is taught otherwise.

An example of using external knowledge to influence a player’s choices comes from the psychological elements surrounding the simple game of Rock, Paper, Scissors. Explained in a passage from the World Rock Paper Scissors Society page, “knowing that there is always something motivating your opponent’s actions; there are a couple of tricks and techniques that you can use to tip the balance in your favour.” These tips and tricks such as suggesting a throw before the game begins, outside of the magic circle, are components of contextual information outside of the game space that can affect strategic choices.

The web series Extra Credits discusses the idea of cyclical imbalance in the game League of Legends. They explain how players may choose a certain champion because of how powerful they are against the average champion, leading many players to choose that particular champion. That same champion has a weakness that can be exploited by players who choose another specific champion. This understanding of the current evolving state of the meta-game provides contextual knowledge an informed player uses to adjust their Strategy.

It becomes a challenge for developers as players develop this understanding, because a player may or may not have that contextual knowledge. Everything from how complex to make a tutorial, how walkthroughs have changed classic adventure games, and issues with accessibility for new players are all affected by how much contextual knowledge a potential player might have. In relation to the rest of the model, the challenge is compounded as every layer is impacted by this contextual knowledge that will alter how and when the player will understand the intended learning.

Conclusion

By acknowledging all these layers a player may learn from, a developer can craft specific experiences to communicate specific information at different times. These layers could be used to craft a more engaging or informative experience by incorporating how each of these layers uniquely affords knowledge to the player.

Based on interaction as an input with an output feedback, each layer provides unique learning opportunities for the player. The core layer, Presentation Aesthetic describes how interaction is

communicated to the player. The next layer, Mechanic is a single instance of interaction. System is all possible interactions. Tactic is a choice of making a single interaction. Strategy is planning for multiple choices of interaction. The final layer, Context is using outside information to influence the players understanding and usage of these interactions.(source:gamasutra)

下一篇:游戏工作室应关注行业中的歧视问题

闽公网安备35020302001549号

闽公网安备35020302001549号