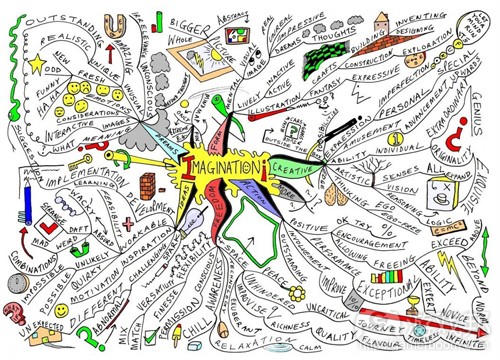

阐述游戏设计虚假表象之想象力

作者:Chris Bateman

游戏设计师是想象力极其丰富的人,也正是因为这样,在对待玩家时,我们经常犯下严重的错误:绝大多数人的想象力比游戏设计师平庸得多。这应该是众所周知的事实了,所以老套的肥皂剧、“记实”电视节目、“真实的”故事和其他仿真娱乐媒体会这么流行——这往往被忽略,以致于许多有想象力的人(无论是不是游戏设计师)感到沮丧,因为想象力丰富的游戏往往在商业上惨败,而逼真的战争FPS却卖得火爆。

我刚开始领悟“想象力是另一种形式的才能”这一说法时,我还是少年。当时我每周都会玩桌面RPG。我的哥哥身体素质好,在几乎任何比赛中的表现都超过我,他说他对我们的游戏有兴趣,但这整个游戏都是口头进行的,他觉得玩不起来。如果游戏能加入小模型,他就能玩,但如果没有,这游戏对他来说就太难了。当时我没有意识到作为才能的想象力有多么重要,但我发现了另一个重要事实:越容易想象的活动,就越多人能够参与。

这就是为什么《第二次世界大战》(或《现代战争》)射击游戏那么成功、赛车模似游戏那么流行、《Wii Sports》那么热门的原因了。任何希望取得商业成功的游戏都有一个简单的任务,那就尽可能减少玩家的想象力负担,想象力要求越低,吸引的玩家越多。甚至明显的例外通常也在想象力要求上有所折扣:《口袋妖怪》是靠丰富的想象力成功的罕例,但它的流行很大程度上是托卡通片的福,后者已经帮助玩家想象了。通常来说,你可以信奉这条原则:想象力要求越多,吸引的玩家越少(游戏邦注:但是,想象力也受其他心理的影响,比如想象力强的人可能有社交障碍之类的问题)。

如果这个关于限制想象力的论断是正确的,那为什么这个世界上还有那么多科幻小说和幻想游戏——更别说少数成功的“模拟真实世界”的桌面RPG了?这类成功的背后有几个因素,但它们都可归结为不同受众的混合。可以简单地认为,想象力最强的人玩想象力要求最高的游戏(如桌面RPG);想象力一般的人可以接受科幻、幻想和恐怖小说那种程度的游戏和控制生动的玩家角色的游戏,但玩纯文字游戏就比较困难了;想象力最差的人需要小说和游戏提供“真实的”内容。《Wii Sports》成功不只是因为它简单的界面,还因为它对想象力的要求低到几乎人人都能满足。

本系列文章是以详述Kendall Walton的哲学作品为基础的,把他提出的“假装的再现理论”运用于游戏设计领域。简单地说,Walton的系统可以概括为:再现媒介——包括玩具、小说、电影、桌面游戏和电子游戏,可以作为具象化想象的小道具。比如,玩玩具枪时,我们想象它是真枪;看《哈姆雷特》时,我们想象丹麦王子与两难的困境作斗争;玩《大富翁》时,我们想象自己正在进行投资大战;玩《Wii Sports》时,我们想象自己正在打网球、保龄球、髙尔夫球等。我们利用各种再现媒介玩“信以为真”的游戏,进入一个用可疑的道具支撑起来的虚构世界中。

我从假装的再现理论的角度看游戏设计,目标不是为了制定一套规范用于约束如何设计游戏——游戏设计没有统一的做法,寻找统一的做法是徒劳的。相反地,我的目的是提供另一种思考游戏的角度(受Walton的理论的启发),和一种承认想象力的作用及其局限性的游戏设计方法。

另外,Walton的理论把小说、电影和其他故事都视作人们玩“信以为真”的游戏道具,据此,所有艺术形式事实上都可以当作一种游戏来考虑。这使得人们对电子游戏的艺术地位的质疑完全失效了,因为在Walton的理论中,所有艺术都是游戏的一种形式。

尽管可以推导出上述结论,但受“假装的再现理论”启发的游戏设计法并不打算成为设计想象力要求较低的大众游戏的系统。游戏市场的现状是,想象力要求较高的游戏确实能够取得商业成功,恰恰是因为想象力更强的玩家比想象力较差的玩家花更多时间和金钱玩游戏,这个情况是不可能改变的。我希望,通过解释这个独特的视角,任何类型游戏的设计师都能找到考虑游戏设计问题的新思路——无论他们的目标是想象力有限的大众玩家,还是想象力无限的小众玩家。(本文为游戏邦/gamerboom.com编译,拒绝任何不保留版权的转载,如需转载请联系:游戏邦)

Game Design as Make-Believe: Imagination

by Chris Bateman

Game designers are tremendously imaginative people, and as such we often make a serious error in dealing with other players: the great majority of people have vastly more ordinary imaginations. This observation – which should be a truism given the popularity of predictable soap operas, ‘reality’ television, true stories and other down-to-earth entertainments – goes unnoticed so frequently that a great many imaginative people (both game designers and otherwise) find themselves expressing dismay that such-and-such a game is a commercial failure while yet another war-based first person shooter racks up mighty sales.

I first began to appreciate the idea that imagination was a talent in varying supply when I was a teenager, playing tabletop role-playing games every week. My older brother, whose physical skills outstrip mine in virtually every context, mentioned to me that he’d be interested in joining our games but he felt unable to do so when the entire game was verbal. If we would play with lead miniatures, say, to represent what was going on in the game, he would be up for it, but in the absence of this it would be too hard for him to keep up with what was going on. I didn’t realise it at the time, but I was discovering an important facet of human imagination: the easier something is to imagine, the more people can participate.

This is the secret behind the success of World War II shooters (and indeed Modern Warfare), the reason for the popularity of games based around real cars, and a key aspect of the appeal of Wii Sports. Any game hoping for astronomical commercial success has an easier task if it minimises the amount of imagination required, and the more that such demands are reduced the larger an audience can be reached. Even the obvious exceptions often have mitigating circumstances: Pokémon is a rare case of a wildly successful imaginative franchise, but its popularity was greatly aided by the accompanying cartoon series which assisted players in visualisation. In general terms, you can count on the formula of ‘greater imagination required, smaller numbers of players attracted’. (Note, however, that there is a psychological trade-off involved in the talent of imagining, and people who are highly imaginative generally suffer from other issues, frequently including problems with social integration).

If this claim concerning the limitations of imagination is valid, why are there so many science fiction and fantasy boardgames and videogames – not to mention so few successful “real world” tabletop role-playing games? There are several factors behind the success of genre fiction in the various games industries, but they all amount to a crossover in audience. As a crude approximation, one might say that the most imaginative people are able to play the most imaginative games (such as tabletop role-playing games), the middle tier is comfortable with the imagination entailed in science fiction, fantasy and horror and the control of a graphical avatar but struggle with the demands of a purely verbal game, while the least imaginative people require “real” content in their fiction and their games. Wii Sports succeeds not only because of its accessible interface, but because it reduces the degree of imagination required to play a videogame to the point that essentially anyone can play.

This sequence of posts, which is based upon a philosophy serial detailing the work of Professor Kendall Walton running in parallel on another of my blogs, takes the make-believe theory of representations and applies it to the field of game design. In brief, Walton’s system can be summarised as stating that representations – including toys, novels, plays, movies, boardgames and videogames – can be understood as props which prescribe specific imaginings. A toy gun prescribes that we imagine it is a real gun. Hamlet prescribes that we imagine the Prince of Denmark grappling with a vexing dilemma. A game of Monopoly prescribes that we imagine a property investment battle. A game of Wii Sports prescribes that we imagine that we are playing tennis, bowling, golf etc. We play a game of make-believe with every kind of representation in which we enter into a fictional world implied by the prop in question.

By looking at game design from the perspective of the make-believe theory of representation, the objective is not to dictate how game design must be performed – there is no unified method for game design, and to seek one is a fool’s errand. Rather, the goal is to offer a different way of thinking about the play of games (one inspired by Professor Walton’s theory), and an approach to game design that recognises the role of imagination and the limitations this implies. Furthermore, since in Walton’s system novels, movies and other stories are seen as props with which people play a game of make-believe, this perspective brings all forms of art under one roof, considering them all as games. This makes questions about the artistic status of videogames (for instance) entirely irrelevant, for all art is a form of game in Walton’s theory.

Despite the observations made above, game design as make-believe is not intended as a system for designing mass market games requiring less imagination to play. The reality of the market for games of all kinds is that more imaginative games do achieve a measure of commercial success precisely because the more imaginative players spend more time and money playing games than less imaginative players, and this situation is unlikely to change. It is my hope that by presenting this unique perspective, game designers working at all corners of the market will find new ways to think about game design problems – whether they are aiming for a wide audience of limited imagination, or a smaller audience whose capacity for make-believe is practically unbounded.(source:kotaku)

上一篇:分析两种游戏难度设置的差异与优劣

下一篇:阐述游戏设计虚假表象之生成原则

闽公网安备35020302001549号

闽公网安备35020302001549号