分析游戏美术人员收入缩水的原因及前景

作者:Steve Theodore(Undead Lab技术美术总监)

据游戏开发者薪水年度调查报告显示,游戏美术人员在去年的平均年薪是7.5万美元。比起美国教师的平均年薪(约5.5万美元),这个数字已经算很不赖了。

此外,这一数字还高于美国劳工统计局公布的“多媒体动画师”(游戏邦注:这包括电影、游戏、网络、广告和其他电脑动画领域的工作者)的平均收入(5.8万美元),如此来看这个数字确实不算寒碜。

“我们的整体薪资并没有提高”

但平均值总是一个值得怀疑的数据。这一领域其实根本不存在所谓的“一般”美术人员——其数据包括了可以得到大笔分红的成功行业元老,以及依靠Kickstarter和信用卡艰难求生的独立开发者。但你还是可以从这些平均值中看到一个真相:我们的薪资水平并没有提高。

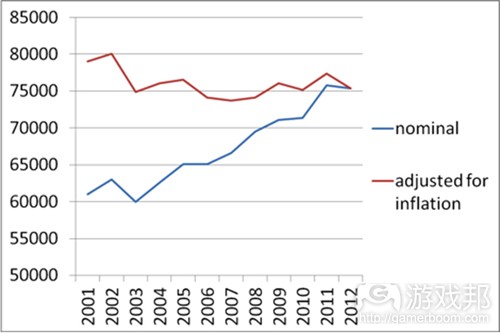

在2001年,美术人员的平均年薪接近6.1万美元。在过去10年中,平均收入提高16%左右。但如果考虑到通货膨胀的情况,这些对比情况就不太乐观了——2001年的6.1万美元相当于今天的7.9万美元。换句话说,我们的平均年薪实际上还比10年前下降了10%左右。

虽然这与经济衰退大有关系,但这一趋势在过去10年中基本上没有变化。如果说要归咎于经济衰退,这一数值的急剧下滑是出现在2003年,而非2009或2010这两个最惨淡的年份。此外,这些数值也大有返回过去的趋势。在千禧年前的多数行业元老可以作证,GC美术人员在20世纪末远比今天更为抢手。

我从1995年开始进入游戏行业,那时候的年薪换算成今天的钱只有7.7万美元。《游戏开发者》调查数据显示现在的美术人员起薪是4.5万美元,也就是说在过去20年中,初级美术人员的年薪下降了45%。

各种原因

现在,你可能会认为我的起薪那么理想,一定与我的美术才能有关,但事实上,那是因为那时候的现行汇率比现在更乐观。

我们可以把Animators Guild(游戏邦注:这是好莱坞的动画师协会,其覆盖范围包括CG美术师)于1997年开始的薪资调查进行对比,当时他们的调查样本每周平均收入高达9.6万美元,相当于今天的13.7万美元——相当于今天游戏领域同行两倍的年薪(但在此要注意,电影行业工作者的生活开销更大,工会会费也很高,并且会频频停工)。

有趣的是,其最近的一次调查数据(2008年)显示,这一行工作者收入相当于今天的9.3万美元。仍然高于我们的平均水准,但却比过去10年下降了三分之一以上。

作为一名美术师,当你努力建立自己的事业时,你很难看到自己的经济情况的宏观走势。我们深深地记得一些情况:自己的奋斗和胜利,成功的冒险,以及那些看似板上钉钉的事情最后却泡汤了。我们也记得这一行总有些付那么点薪水的公司,以及在自己大手大脚挥霍的同时,炒掉我们兄弟的老板。

但我们却一直没看到这一行发生什么驱动我们未来的巨大转变。平均值、调查等情况可以让我们了解一些隐性压力,以便让我们更有效地规划自己的事业。在这种情况下,这种平均值却真是让我们脊背发凉。

游戏领域的文化环境和发展前景(尤其是游戏美术师)成形于特殊的历史时期。在90年代,能够运用复杂的软件以及晦涩难懂的3D建模技术的人才明显供需不足。计算机图像刚从学术研究范畴延伸到娱乐领域,虽然风靡一时的TRON与1982年开始露面,电脑成像直到《终结者2》(1992年)、《侏罗纪公园》(1993年)以及《玩具总动员》(1995年)问世时才真正虏获了大众的想象力。

当时传授这种工具操作课程的学校也非常之少,即便那些学校能够找到辅助实践的外部工作站以及价格不菲的软件,也找不到足够有经验的用户来传授这些课程。

而在学校之外,业余爱好者和发烧友也很难找到适合自学的工具——当时完整版的Alias PowerAnimator(Maya的前身)几乎是一辆新凯迪拉克的价格,并且需要一个成本相当于新野马敞篷车的Unix工作站。

所以这并不令人意外,由于正规教育及非正规自学教育的欠缺,电脑美术人员当时非常之少。任何人只要掌握了运行SGI工作站的技能,或者有耐心应对这类软件程序,都可以在那些对新兴技术不甚熟悉的公司找到工作。

CG领域(尤其是SIGGRAPH)的人才市场由好莱坞和大型电视制作公司主导,其竞争之激烈相当于NBA选秀。当时可以制作出体面画卷的任何人都可以得到很拉风的办公间,享受豪华派对,获得签约资金。唯一令人遗憾的是,许多美术人员都必须像车间技术工而非“真正的艺术家”一样顶着压力辛勤劳作。但总体来看,当时真是CG美术人员的黄金时代。

竞争激烈

但在最近十几年,情况就没有这么乐观了。由于通货膨胀,大家的薪水普遍降低。想象一名美术师仅靠356天为一款AAA大型游戏进行第N次迭代而一夜暴富,这简直是痴人说梦(事实上,还有许多手机和休闲游戏开发者梦想着自己能够推出下一款《愤怒的小鸟》或者《英雄联盟》)。毕竟,这一行已经不再欠缺富有才华的电脑美术人员——看看那些失业求职的同行就知道了。

之前这一行很缺美术人员,是因为那时候整个行业本身都是新生事物,准入门槛很高。老派美术师基本上是自学成才,四处搜集信息,他们是通过不断试错而掌握经验。

但今天,教育行业已经提供大量此类课程,传授各种软件用法,并且颁发相关学历证书——这也成为年轻美术人员求职的必需要求。有些学校要求学生掌握扎实的传统美术功底,以及最新的软件技术,而有些学校却不过是文凭工厂,压榨学生的助学贷款,消费他们从小立志进入游戏行业的满腔热情。

游戏行业元老对当今美术教育的怀疑不无道理,尤其是考虑到这些教育课程的收费标准——比起90年代相当于豪华轿车的工作站成本,一所平庸职业学校的电脑动画文凭两年的6万美元学费,确实不算什么很大的开销。

但这些学校就是改变了行业状况,培训出许多拥有正当技能的年轻美术人员。这更便于雇主挑选人才,对于游戏消费者而言,那就意味着这有助于制作出更好看的游戏。不幸的是,对我们来说,这也压低了我们的薪资水准。这就是市场供应与需求法则。

传统上看,我们这个领域并不是很看重学历,我们当中许多人是因为热爱游戏而自学成才。这种自我激励因素为游戏美术领域倾注了热情与动力,同时也扩大了准美术人员的供应量。游戏也变成更易于向业余爱好者、发烧友和独立开发者进入的领域。

现在我们也很容易找到一些传授3D和游戏制作课程的业余培训机构,心怀抱负的孩子甚至不需要上学,通过上网就能获得大量关于软件及美术的教程,讨论网站以及远程教育。他们还可以获得许多免费、高质量的学习工具(游戏邦注:例Source Filmaker、Sketchup、Unreal SDK)。

反思

今天富有生气的高端业余爱好者社区产出了许多杰出的美术人员和创新作品。这也不幸抬高了我们这些美术师的求职门槛。多数职业美术人员与他们比较自己的作品集时,都应该进行一轮反思——我们的作品是顶

着截止日期、技术限制,有时候是艺术方向争论等压力而完成的,可这些发烧友却能够投入6个月时间不断润色某个单一的造型。比起十年前,现在已出现了更多高质量的CG美术作品。所以,市场供需的铁律再一次夺低了我们的身价。

感到很受挫?这里我们还没有提到自动化、外包,以及从大型AAA游戏转向小型手机/社交游戏项目的美术人员呢。

我们必须接受一个现实:这一行的开荒期已成为过去时。劳工统计局预测在未来10年,电脑图像和动画制作领域的招聘率将增长8%左右,整体将增长16%。我们现在已经不算是一个发展中的领域。游戏行业瞬息万变,小型工作室和小型项目正在取代过去的大型AAA游戏领域。

即便如此,还是有许多美术人员难以割舍过去那种位居主动权的心理。乐观主义和雄心抱负导致我们很难在情感上接受自己所处的领域已经趋于饱和,并且收入已经今非昔比这一事实。

这并不是说你将在一夜间失业,或者说所有的新计算机美术学历都变成废纸了,而是指未来的学生应该深谋远虑,在入学之前仔细掂量下6万美元的学费究竟值不值当。

股市观察者和行业分析师认为游戏领域在未来数年还会再次雄起,未来仍会有岗位需求和商机(不过多数发展机遇集中于手机和网页游戏,而这些领域的薪水普遍低于AAA游戏项目)。但是,即使游戏销量上升也不会让时光逆转,将我们的薪水提升到之前繁盛时期的水平。

关键在于我们必须现实看待自己在这一竞争日益激烈的领域中的前景。从当前的情形来看,盲目相信运气,认为游戏是一个“大行业”并非可行的出路。

努力才是出路

未来十年的美术师需要持续提升自己的技能,跟上游戏行业的技术潮流和趋势,并仔细思考如何自我推销。他们需要以更清醒的头脑应对赶工期,因为我们从一款游戏中得到的回报正在减少,我们为工作而牺牲家庭生活和个人健康的意愿也在消退。许多人会从独立和手机游戏领域寻找更大风险,更多回报的机会。也有些人会服输认命,甘愿接受或多或少的报酬。

不知道老派游戏文化在美术人员更不值钱的未来时代究竟能否幸存。我们希望乐观、幽默和热情的典型美术人员不要屈从于这种更低的期望。休闲、手机和社交游戏仍可留存许多由传统游戏投奔而来的人才。希望他们能够担起让游戏文化不变质的责任。

即使是AAA大型游戏美术人员也要记得过去那些雕画飞龙,为飞船添翼的时光,永远不要忘记:世上没有所谓的一般美术或一般游戏。我们进入这一行并不是要做一般的工作。努力吧,一切都会好起来的。(本文为游戏邦/gamerboom.com编译,拒绝任何不保留版权的转载,如需转载请联系:游戏邦)

The downward salary slope for game artists

By Steve Theodore

A reprint from Gamasutra’s sister publication Game Developer magazine, this article from Steve Theodore, technical art director at Undead Labs, explores the history of game artist salaries, and where they’re headed next.

The annual Game Developer Salary Survey always makes interesting reading. As of last year, the average annual salary for game artists was about $75,000. That’s a pretty respectable average – it compares favorably with the average salary for teachers in the U.S. (around $55,000).

It’s also notably higher than the average given by the Bureau of Labor Statistics for “multimedia animators” – which includes film and games but also web, advertising, and other kinds of computer animations, and is quoted as $58,000. So, it’s hardly a terrible number.

“Our wage picture is not improving”

But averages are always suspect. There’s no such thing as an “average” artist – these numbers include both successful veterans with fat profit-sharing checks, and struggling indies living off of Kickstarter and Visa cards. However, there is one thing you really can see by looking at those averages: Overall, our wage picture is not improving.

Back in 2001, the average artist salary was close to $61,000. In the last decade the average has increased by 16% or so, and when you adjust for inflation, the comparison isn’t so rosy: $61,000 in 2001 dollars is around $79,000 today. In other words, the average salary has actually slipped by almost 10% in real terms from where it was a decade ago.

Artist salaries have been increasing. However, adjusted for inflation, they’re actually falling.

It’s tempting to blame the decline on the recession, but the trend is actually consistent across the whole decade. The biggest dip doesn’t appear in 2009 or 2010 (as you might expect if the recession were to blame); it’s actually in 2003. Moreover, that trend line goes back even further. Most veterans of the premillennial days (your humble columnist included) can tell you that the market for CG artists was a lot hotter back in the closing years of the 20th century.

I started in games in 1995, and my starting salary back in those distant days works out to just over $77,000 in today’s dollars. The Game Developer survey puts today’s starting salary’s average at around $45,000. That’s a decline of over 45% in real terms over the last couple of decades.

Ouch.

Double ouch

Now, you might think that cushy starting salary of mine was a recognition of my sheer artistic genius… or perhaps I might like you to think that. The truth, however, is that the going rate in those heady days was a lot heftier than it is today.

For comparison’s sake, the Animators Guild (the Hollywood union that covers CG artists) started doing their own salary surveys in 1997, and they report an average weekly rate that works out to a whopping $96,000 for that year, equivalent to $137,000 today – just about twice today’s average for games. (Of course, before you book your tickets to L.A., remember that film work comes with a high cost of living, union dues, and frequent periods without work.)

The really interesting (or rather, really depressing) point here is that the latest number in their data, for 2008, works out to about $93,000 in today’s dollars. Sure, it’s still higher than our average, but it’s a drop of more than one-third in a decade. Double ouch.

Hollywood CG animator salaries, as reported by the Animator’s Guild, have fallen by nearly a third over the last 15 years when you take inflation into account.

As an individual artist, when you’re trying to make sense of the business you’re in and build a career, it’s hard to get a good view of the macro trends that are shaping your economic life. We see the details: We remember our struggles and our triumphs, the successful gambles and the jobs that looked like sure things but turned out to be disasters. We remember companies that paid stupid money and the shady chiselers who bought Porsches while laying off our friends.

What we don’t always see is the way that larger shifts in the business are driving our futures. Averages, surveys, and the like help us make sense of all those hidden forces so we can plan more effectively for ourselves and our careers. In this case, the averages tell us a pretty scary tale.

The blog entry on the Animator’s Guild web site that posted the Hollywood CG salary numbers ended with this laconic observation from Steve Hulett, the business representative of the animator’s union:

“Soak them in and draw your conclusions. (The one I draw is: ‘The laws of supply and demand have weight and meaning.’)”

This is, sad to say, a profound meditation on our situation.

The culture and outlook of the game business in general, and of game artists in particular, formed in a unique historical moment. In the 1990s, the demand for people who could work with the clunky software and arcane processes of 3D modeling and animation vastly outstripped the supply. Computer graphics had only just emerged from academic research into the entertainment realm; although cult favorite TRON debuted in 1982, computer-generated imagery really captured the public imagination with Terminator 2 (1992), Jurassic Park (1993), and of course Toy Story (1995).

Back then, there were few schools that taught the tools of the trade – and even when the schools could find the money for exotic workstations and pricey software, there were few experienced users to teach the courses. I recall, with particular secondhand embarrassment, an “Advanced Computer Graphics Workshop” at the Rhode Island School of Design circa 1992, which consisted mostly of watching the professor rifling nervously through a thick Wavefront manual.

Outside the schools, hobbyists and enthusiasts were hard-pressed to find tools that would let them learn on their own: a fully tricked-out seat of Alias PowerAnimator (the predecessor to Maya) ran in the same price range as a brand-new Cadillac, and it required a Unix workstation that cost about the same as a new Mustang convertible.

Unsurprisingly, with few opportunities for formal education or informal self-teaching, computer artists were a rare breed. Anybody who could master the esoterica of running an SGI workstation or had the patience to wrestle the beastly programs of the era could find a job with companies who were grappling with the new and unfamiliar technology.

The meat markets of the CG business – particularly SIGGRAPH, where Hollywood and big TV production houses did the bulk of their recruiting – were as competitive as the NBA draft. Anybody who could produce a reasonable reel was aggressively pursued with swanky hospitality suites, lavish parties, and signing bonuses. The only dark lining to this silvery cloud was that many artists had to labor (not always unjustly) under the perception that they were merely software jockeys and not “real artists.” All in all, though, it was a pretty good time to be in CG.

High competition

Fast-forward a decade or two, though, and the picture is a lot less rosy. Wages, as we’ve said, are slowly falling relative to inflation. It’s harder to imagine yourself becoming an overnight millionaire as artist #356 working on the seventh iteration of a triple-A behemoth (though, to be fair there are a lot of mobile and casual devs imagining how it will feel to be the next Angry Birds or League of Legends). Above all, there’s no shortage of talented computer artists any more – just ask any former colleague who’s had to hit the job market recently.

It used to be hard to find artists because there just weren’t that many of us. Not only was the field itself new, it was quite hard to get into. Old-school game artists were largely self-taught, scrounging for information wherever it could be found; they operated on trial-and-error and learned on the job.

Today, though, there’s a huge (and growing) educational industry that offers coursework, access to the right software, and of course official credentials – which are rapidly becoming a necessity for young artists looking to break into the business. Some schools provide a solid foundation in traditional art and the most up-to-date tech, while others are little more than diploma mills making bank off of cheap student loans and the eagerness of kids who have grown up on games to get into a business they idolize.

It’s easy for game industry vets to be cynical about the art-education business, particularly given the cost – at $60,000 for a two-year program, a degree in computer animation from a mediocre vocational school isn’t a huge bargain compared to the luxury-car level cost of setting up your own workstation back in the 1990s.

Like them or not, though, the schools have changed the landscape: There are a lot of young artists out there with reasonable reels and decent technical skills. That makes it easier for employers to be picky and, if you’re a game consumer, it means better-looking games. Unfortunately for us, it also keeps wages down. That’s the law of supply and demand for you.

Traditionally, we have not been a degree-heavy business; a lot of us are here because we love games and taught ourselves how to make them. The wannabe factor gives game art enthusiasm and drive – and it also expands the supply of would-be artists. Games have become infinitely more accessible to hobbyists, enthusiasts, and indies.

It’s easy to find after-school programs and camps that teach the rudiments of 3D and game creation to middle schoolers. Ambitious and motivated kids don’t even need to go to school – the internet offers an unimaginable bounty of tutorials, discussion sites, and online classes for every piece of software and genre of art. There are plenty of free, high-quality tools to learn with, from Source Filmmaker to Sketchup to the Unreal SDK.

Soul-searching

Today’s vibrant and sophisticated hobbyist communities produce amazing artists and innovative work. Unfortunately this, too, raises the bar for us working schlubs who have to pay the mortgage. Most of us professionals have had to do some soul-searching when we compare our portfolios – done under deadline pressure, technical constraints, and sometimes under debatable art direction – with the highly polished work of enthusiasts who can spend six months perfecting a single sculpt. There is a lot more high-quality CG artwork around now than there was a decade ago – and once again, the iron law of supply and demand keeps prices down.

Depressed yet? We haven’t even mentioned automation, outsourcing, or the shift from big console games to smaller, less content-intensive mobile and social titles. Oy vey.

The fact is, the Wild-West boom days are behind us. The Bureau of Labor Statistics is predicting that the employment in computer graphics and animation will grow by about 8% over the next decade – compared to 16% overall. We’re not a growth field anymore. The game industry is changing quickly, as smaller studios and smaller projects are replacing the triple-A behemoths of the last decade.

Even so, losing the bull market mentality that is built into the game industry’s DNA is difficult. Optimism and ambition are such a basic part of what we do that it’s emotionally quite hard to face up to the fact that our cozy little niche is a lot more crowded – and hence a lot less lucrative – than it used to be.

Now, this does not mean your job is going to disappear overnight, or that there is no future for the products of all those new computer art degree programs. It does mean prospective students ought to think long and hard about the wisdom of spending $60,000 or more on a degree!

Stock watchers and industry analysts think that the business side of games will start picking up again over the next few years. There will be jobs and opportunities in the future (though a lot of the growth is going to be in the new frontiers of mobile and web gaming, where salaries are lower and triple-A cred counts for less). However, even an upturn in game sales isn’t going to reset the clock and push wages back to the level they were in the boom days.

The upshot is that we have to be realistic about our prospects in an increasingly crowded field. Trusting in luck and a vague sense that games are “big business” isn’t a viable strategy under today’s conditions. This can be especially hard for vets whose emotional ties to the business were forged in headier times.

“Kick enough ass, and things will work out

The artists of the next decade will have to be constantly upgrading their skills, keeping up with changing tech and trends in games, and thinking hard about how to market themselves. They’ll need to have a clear-eyed approach to things like crunch time; as the rewards of working on a game become smaller for many of us, our willingness to sacrifice family and health for the cause diminishes apace. Many will seek the higher risks and higher rewards of indie and mobile games. Some will throw in the towel and go on to careers that pay better or demand less.

It will be interesting to see how much old-school game culture survives in the less-expansive times ahead. We can hope that the optimism, humor, and enthusiasm that typify game artists won’t succumb to the gray fog of lowered expectations. Casual, mobile, and social games still retain a lot of the shoot-from-the-hip gusto of earlier times. Let’s hope they keep game culture from getting stale.

Even triple-A dinosaurs need to remember that it’s pretty damn awesome to spend your days painting scales on dragons and adding fins to spaceships compared to, say, preparing tax forms for a living. And never forget: There’s no such thing as an average artist or an average game. We didn’t get into this crazy art form to do average work. Kick enough ass, and things will work out. (source:gamasutra)

闽公网安备35020302001549号

闽公网安备35020302001549号