游戏设计师应兼顾动作与弧的执行效果

几乎每款游戏实际上都是两种游戏的合体,一者是以分钟为计算单位的游戏,另一种则是整个游戏主体。我听过不少关于这两者“谁更重要”,以及哪一个应该成为设计师“主要关注点”的争论,我决定在此谈谈我的看法。

嵌套游戏

多数游戏可以视为由一系列更小的内部相互交集的游戏组合而成的整体。例如,美式足球:每个动作都是一个游戏,每场比赛都是一个游戏,每个季赛都是一场游戏。换成你的标准数字角色扮演游戏:战斗是游戏,探索也是一种游戏,升级/创建角色也是一种游戏。

任何游戏都可以分解出无数种嵌套游戏。这其实主要取决于你如何定义“游戏”。无论你可以在游戏中鉴别出多少种独特的游戏,最重要的也只有两种元素:动作和弧。

动作很容易定义:就是你多数时候做的事情。通常而言,你接触游戏头5分钟就会开始执行操作(我曾听说过,未能让你在这个时间内执行动作的游戏就是糟糕的设计)。这些动作一般比弧度更少依赖大脑活动,它更多的是一种本能。动作的持续时间也更短,但时有重复。你可以在数秒或者数分钟时间内体验一种重复的动作。

弧

相比之下,弧的概念更难定义。它是玩家所理解的“游戏”,即玩家继续玩游戏的理由。它发生的时间跨度更长,如果完成了,就意味着玩家对该游戏的粘性已经走到终点(游戏邦注:即当我们感觉这个弧已经完成了,我们就很少再登录贴,或者将游戏弃之一旁)。弧在游戏中通常占据更大比重——在优秀的游戏中,它就是我们不玩游戏时也会想起来的游戏环节。

我们可以将弧模糊地定义为“玩家对游戏重点的看法。”

哪一者更重要?

我认为在这两者中,动作显然更为重要。如果我在开发游戏时,有人问我:“我们可以优化一下动作或者弧,哪一个优先?”我肯定会毫不犹豫地回答:“动作”。

为什么?因为弧正是引起我们兴趣的元素,它是让游戏可持续发展的元素。正是我们继续玩游戏的原因……问题是如果没有动作也就不存在所谓的弧了。如果动作很糟糕,那就没有人会去体验弧。想象在一款带有奇幻角色系统和升级树的MMORPG中,其战斗系统令人麻木,失望和无聊透顶。那就没有人会仅仅为了完成弧而去将任务刷到60几级。

现在让我们看一下相反的情况:《洛克人》、《大蜜蜂》或象棋。我们很容易将这些游戏视为“所有动作”,但这种说法对我们的玩家和人类群体就太不厚道了。人类拥有惊人的情境化能力,我们通常要靠玩家来创造他们自己的弧。

相信不少人都曾多次玩过以上提到的几款游戏,目标就是为了提高自己的游戏技巧。他们精心设计玩得比上次更好的策略,想出新招术,在玩的过程中观察游戏以便完善自己的技能。事实上,我们不难发现人们会在完成游戏许久之后还在剖析游戏,只是为了回味这一过程。如果动作设置得够好,我们就可以将这种学习过程变成自成一体的元游戏。

我们应该时常采取这种做法吗?绝对不是。最好是创造一个覆盖在动作之上的弧,而不是强迫玩家为自己创造一个弧。我只是认为寄希望于让平庸的动作来支持出色的弧,并非可行的做法。

在我们下结论之前,我想谈谈关于将游戏设计视为把多个连锁游戏相组合在一起的话题。对我来说,如果你有足够的时间和资源将所有的子游戏执行到位,那确实是好事。你组合的有趣子游戏越多,玩家就越可能发现吸引他们的弧。

注意这里的子游戏与迷你游戏极为不同。游戏主体是由多个子游戏组成的整体,而迷你游戏则是人们玩腻游戏时,供其消遣解闷的的活动,子游戏是玩家在游戏过程中的不同关注点。

当然,拥有两个紧密衔接的子游戏总好过拥有一大批组织松散的子游戏,或是彼此毫无关联的子游戏。

总结

动作是我们玩游戏的操作,而弧则是我们玩的原因。对于制作好游戏来说,这两者的作用都不容忽视同。这些并非静态的实体,他们会随游戏的发展而变化——对玩家来说,弧甚至可能发生彻头彻底的变化,但无论我们体验哪款游戏,这两者都是必不可少的元素。

优秀游戏与糟糕游戏的一个关键区别就在于,动作与弧的质量优劣。玩家可以自我创造一种令人愉悦而丰富的弧,但却无法自创一套拥有同种效果的动作。所以我认为动作应该成为设计师考虑的第一要务。

在此我要声明一下:在有限的动作范围中创造有意义的体验是更为困难的任务。我个人很喜欢通过电子游戏表达有意义、长久的体验。这包括找到向动作倾注情感的同时,在弧中情境化这种情感的方式。这是一项要求设计师将弧和动作视为基本相同的特殊任务。如果我们打算创造有意义的游戏,我们就一定要放下哪个更重要的想法,尽全力兼顾两者的要求。

原文发表于2007年8月8日,所涉事件及数据以当时为准。(本文为游戏邦/gamerboom.com编译,拒绝任何不保留版权的转载,如需转载请联系:游戏邦)

GAME DESIGN: The Long and Short of It

When is one game two games? Almost all the time, claims James Portnow in this week’s latest game design column. But which of those games is more important?

Almost every game is actually two games, one being the minute-to-minute game and the other being the broader overall game. I’ve heard so much debate about which one is “more important” and which should be a designer’s “main focus”, that I’ve decided to put my two cents in.

Remember, there’s no fact in this article, just opinion supported by what passes for reason around here… In the end you’ll have to make up your own mind.

Game Nesting

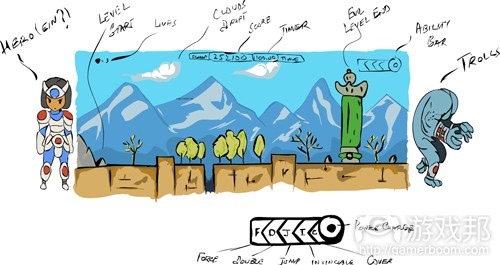

Most games can be viewed as a series of smaller interconnected games that are tied together to make one unified whole. Consider, for example, American football: each play is a game, each “game” is a game and each season is a game. Now consider, if you will, your standard digital role-playing game: combat is a game, questing (1) is a game and leveling/character building is a game.

There is no limit to how many nested games any given game may contain. It’s largely a matter of perception anyway – and of how you define “game”. The important thing is that no matter how many unique games you’ve identified within a game, only two really matter: the action and the arc.

The Action

The action is easy to define: it’s what you’re doing most of the time. Usually you will start experiencing the action within five minutes of picking up a game (In fact, I’ve heard arguments that it’s bad game design if you don’t… I can think of arguments to the contrary though). The action is usually slightly less cerebral than the arc, engaging you in a more visceral way. The action is also brief in duration but often repeated. You can fully experience one iteration of the action in a matter of minutes, if not seconds (2).

The Arc

The arc is a little harder to define. It’s what the player understands to be “the game”. Often the arc is the reason a player continues playing a game. It takes place over a much longer span of time and, once completed, usually the signals the end of the player’s engagement with that particular game (when we feel the arc is complete we let our accounts go inactive or put the game back on the shelf). The arc is typically the headier portion of the game – in really good games it’s the section we think about when we aren’t actually playing the game.

The arc can be vaguely defined as “what the player views the point of a game to be”.

So, Mr. Portnow, Which is More Important?

I’m going to argue that the action is definitively the more important of the two. Were I working on a game and someone said to me, “We can perfect the action or the the arc. Which should we perfect?”, I would quickly answer, “The action.”

moscallout”Were I working on a game and someone said to me, ‘We can perfect the action or the the arc. Which should we perfect?’, I would quickly answer, ‘The action.’”/moscalloutWhy?

After all, the arc is really what holds our interest. It’s what makes a game sustainable. It’s why we continue to play… The problem is that there can be no arc if there is no action.

If the action is bad no one will ever experience the arc. Imagine an MMORPG with a fantastic character system and leveling tree. Now imagine that the combat in that MMO is mind-numbingly, nay, painfully boring. No one’s going to grind through sixty levels of an MMO just to complete the arc in the way it was intended.

Now let’s take the opposite case: let’s examine games like Pac-Man or Galaga or chess. It’s easy to see these games as “all action”, but that does an injustice to our players and to our species. Humans have a remarkable capacity for contextualizing things. Often we can rely on our players to invent their own arc.

Very few people play any of the above-mentioned games once. Rather they play them again and again with the object of improving at them. They devise ways to do better than the last time.

They come up with new strategies, observing the game as they play it in order to better their skills. In fact, it’s not uncommon to find people dissecting an individual game long after it’s been completed in order to fit it into their arc. If the action is good enough we make learning its own meta-game.

Should we do this often? No. Not at all. It is far far better to have a well crafted arc to lay on top of your action than to force the player to invent an arc for themselves. I’m simply saying it’s impossible to go the other way, hoping to get away with mediocre action to underpin your brilliant arc.

Back to the Beginning

Before we conclude, I want to just touch on the topic of designing a game as a composite of multiple interlocking games. To me this is always a good thing, assuming that you have the time and the resources to execute all of your sub-games well. The larger your pool of interesting sub-games, the more likely the player is to be able to find the arc which most engages them.

Note that sub-games are very different than mini-games. Mini-games are distinct from the main game whereas these sub-games are an integral part of it. Mini-games become something for the player to do when they are bored of playing the game; sub-games are different games for the player to focus on while playing the game.

Of course it’s always better to have two well connected sub-games rather than a ton of loosely joined or, worse yet, unconnected sub-games.

And the End

The action is what we play, the arc is why. Both are vital to make a great game. These are not static entities. They can evolve over the course of play—the arc can even change entirely for a player—but they are always present in any game we partake in.

moscallout”The action is what we play, the arc is why.”/moscalloutOne of the key differences between a good game and a bad game is the quality of the action and the arc. The player can invent a perfectly satisfying and rich arc for themselves. They cannot do this with the action. Ergo I argue that the action should be the principle focus of the designer.

That said, I’ll leave you with a personal conceit: it is much harder to create something meaningful within the limited scope of the action. Many of you who have read my column before know that I am personally interested in conveying meaningful, lasting experiences through video games. This involves finding ways of putting emotion into the action while contextualizing that emotion within the arc. This is a monumental task that requires that the designer view the arc and the action as fundamentally the same. So, if we are ever going to create truly meaningful games, we must be willing to put aside the question of which is more important and devote ourselves to both.(source:edge-online)

下一篇:全方位总结成功独立游戏的设计经验

闽公网安备35020302001549号

闽公网安备35020302001549号