论述免费游戏盈利三角框架的含义与意义

作者:Tadhg Kelly

我常常发现,免费游戏设计的每次互动都是一种潜在盈利渠道。这些游戏想要出售能量、增益魔法、解锁角色、美观的道具、规则调整、经验值等物品。通常,这主要源自开发商试图为游戏获利。

其实,创造多种盈利渠道是件好事,但逾越某个要点就会将其转变为付费取胜手段。此时,游戏失去价值,玩家也失去游戏动机。你可以在游戏中出售大量物品,但重点是,你至少应维持某个维度不在销售的范围内,确保玩家拥有体验动机。为此,我创造了免费游戏的三角框架,借此,你可以明智地检验自己的盈利模式是否合理。

付费作弊的劣势

作弊与利用两者之间存在巨大差异。作弊是一种脱离游戏情况的影响力,它会颠覆整个游戏,造成赢家总属于同一个人或多个人。作弊是种不公平行为,它掠夺了玩家的体验动机。同时,它有力地打破游戏的神秘面纱,向所有玩家暴露游戏的整体框架,破坏神秘感。

而利用则是一种符合游戏情境的影响力。它具有奇特的规则结果、意想不到的实验结局,以及自发性的复合效应。玩家可以利用大脑思维解读并掌握游戏系统,只要它不会演变为独霸策略,利用总能发挥积极作用。

从某种意义上说,有趣的游戏系统是建立在利用手段之上。

出色的免费游戏设计可以定义为“付费利用”,而糟糕的设计则被称为“付费作弊”或“付费取胜”。付费利用有助于玩家节省自己在游戏中的开支,而付费作弊只会破坏整款游戏。

在付费利用模式中,玩家无法转变游戏的挑战方式。他可能会购买更多的扑克筹码,但他仍得为了取胜加入游戏进程。更加强大的剑可能会降低作战难度,但玩家仍得参与实际战斗。游戏仍会保持其魅力、压力与解决问题的需求。因此,游戏动态仍保持完整性。

附属效应

典型的付费利用模式包括让玩家购买自己缺少的某项资源,否则他们就得通过刷任务来获得资源。通常,玩家可以利用硬货币(游戏邦注:比如“现金”或“金币”)购买,由于购买商品十分容易,而赚取金币则存在难度,因此游戏会鼓励玩家通过利用行为获取金币,但同时需确保游戏的趣味性。大多数开发商都理解这个原理,但却设计出付费作弊的盈利模式。

这种情况主要发生在三个方面:

首先是游戏失去平衡。开发商可能会出售可以在游戏剩余进程中使用的特殊武器,或是出现设计师从未料想到的用例,即出现独霸策略的结果。我们很容易发现这类付费作弊行为,但却难以进行修改。如果某些顶级玩家在开发商调整这些手段前,就已购买了这类道具,那就会产生糟糕的客服问题。

其次,多种购买模式会产生累加效应,引发付费取胜的现象。假如你既可以购买更加精良的剑,同时可以利用它打败大boss。或者你可以在获得一把强大的刀剑同时,购买升级所需的经验值,那么整场战役就变得微不足道。假如你可以重复这些行为。那么游戏会因此失去趣味性。

最后,游戏有意创造出付费作弊的盈利模式。在此,开发商有意给所有行动明码标价。有趣的是,这通常被阐述为玩家的选择。开发商表示,如果玩家可以依靠付费通关,这是多大的事情?这不过是玩家的选择,他们的游戏,他们的游戏时间,对吧?

直到参数显示用户留存率逐渐减少,付费作弊行为才得到遏制。如果你制作的游戏只包含供玩家购买的灵活定制内容,那么它就失去了游戏的意义。游戏本质属于娱乐性活动,它应为玩家传递真正的价值。

玩法限制

趣味性是指“获得取胜的快乐,同时保持公平的游戏动态”。趣味性是玩家感受到的所有快乐之一(游戏邦注:其他还包括探索、快乐、美丽、激动、共鸣等),但它属于基础性的快感。任何可以让玩家在媒介上体验,或长久体验的游戏,都必须充满乐趣。

某些经济学家认为,收取一切费用似乎属于完全合理的做法,它可以吸引“鲸鱼”玩家,保持他们持续付费。如果游戏的每个部分都需付费,那么玩家将需要买下游戏的所有部分。然而,游戏设计师知道,如果所有紧急事件需依靠花钱来解决,那么无论是对于鲸鱼玩家或是小鱼玩家,游戏的趣味性都已荡然无存。

设计精良的趣味具有多种维度。它认可不同互动形式相互影响产生的策略,导向自发性结果和战略。在单一维度的游戏中,玩家只能依靠刺激性大奖(彩票),或者要求运用肢体技能(许多体育项目)获得乐趣。找到乐趣的关键在于,测定是否可以利用多维度的互动方式解决紧急事件。

我们还可以利用“限制点”看待这些挑战模式。任何经济模式都存在限制点,即过量供应产品会导致价格波动。在免费游戏中,该词语通常用于描述高价产品常让玩家退而求其次,转向其他价位产品的情况。

同时,游戏挑战中也包含限制点:玩家必须为了获得乐趣而精通这些艰难的挑战模式,他们乐意为了通关以高价购买时间、技能或资源。鉴于此,为了保持免费游戏的趣味性,游戏至少应保证某个限制点不在购买范围内。这就是三角模式的作用所在。

三角模式

开发者们常在项目管理中提到:“快速、廉价、出色。你只能从中选择两种。”

虽然每个项目都具有复杂性,但这些简单词语却可以定义与之相关的3个常见维度,并规定只有两个元素可以保持不变。如果你拥有较少预算,且需要快速得出结果,那你就不能期望游戏存在大量功能。如果你需要游戏体现出杰出功能,且截止期限十分短暂,那你就得为此支付一定费用。那样才能确保游戏品质。

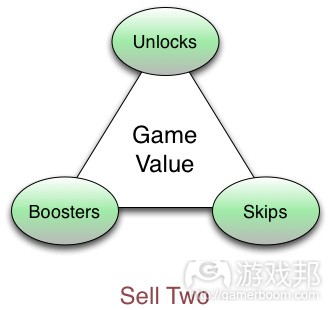

最近,我决定利用三角模式描绘免费游戏的盈利模式,确保游戏设置存在某些无法进行购买的限制点。如果你可以按照这个模式约束自己的行为,那你就不大可能创造出付费作弊的盈利模式。

模型如下:

增效剂

增效剂是指短期性的增强效果。它可以是只含些许子弹的特殊武器、坚不可摧的短期盾牌,或是可以把蓝宝石变为红宝石的令牌等等。增效剂是动作/街机游戏的主要特征,它通常用于短暂地扩展游戏的基本动态。同时,不少游戏也鼓励玩家采用战术,它们为玩家提供存储增效剂的库存区域,方便他们在需要时使用。

比如,《宝石迷阵:闪电战》支持玩家利用硬货币购买增效剂。它们有助于玩家清除整行宝石,极大地改变游戏环境,同时为玩家增加分数。然而,玩家仍得在1分钟内连续配对3组宝石。这便是游戏设置中存在的限制点。

另一个例子是购买筹码。比如,在扑克与老虎机游戏中,玩家可以利用筹码作为赌注,寄希望于从中赢取更多金钱。当玩家输掉赌注后,他常常会购买更多筹码,提高自己的获胜机会。也许他会成功,但这些额外筹码只具备短期效果。

解锁模式

虽然增效剂只具有短暂效应,但解锁模式却具备永久功能。玩家可以通过解锁模式获取道具或特性,这会影响其剩余的游戏进程。比如,在模拟社交游戏中,玩家用于填充游戏环境的道具会在其达到一定级别后得到解锁。她必须长时体验游戏,积累经验值,直到获得这些道具。或者,她可以经常性地支付硬货币,从而早点达到这个目标。

解锁模式涵盖许多区域,比如在《CSR Racing》中,新型车辆可以优化游戏世界。再如,《Temple Run》支持玩家购买升级功能,进行物品收集。一般而言,模拟游戏支持玩家通过付费模式早点解锁特定建筑。接着,玩家会面临土地与资金短缺问题,但这些都受到人口或土地资源等整体规则的控制。

跳过

免费游戏出售的第三种模式为跳过:最常见的当数利用“能量”跳过。游戏常常会在一段时间限制玩家进行具有高度价值的操作(比如收获、或建造),而后每隔几分钟(通常为5分钟)产生1个经验值。游戏会以较低价格向玩家出售能量,玩家可以借此延长游戏时间。

跳过的第二种类型为“社交回避”。有些社交游戏包含了一些特定活动,它们需要玩家获得好友帮助。本质上,游戏提供了一个选项:让玩家要求好友点击某个游戏广告(如同Facebook请求),或者玩家可以付费跳过这一模式。

无论是能量,还是社交回避,它们都不具备价值。相反,它们只是告诉玩家“如果你想要体验更多模式,你必须付费,或是做一些事”。结果,跳过成为社交游戏中最具欺骗性的方式之一。比如,社交回避会导致团队中的好友各做各事。由于这些属于相当低俗的手段,所以免费游戏在那些自封为“玩家”的群体(即硬核玩家)之中并不盛行。

然而,免费游戏中也存在一些较好的跳过类型。

其一是“等待时间”。在此,玩家可以按照自己的需求与游戏保持长时互动,但他采取的行动会受到时间控制。比如,必须建造大楼、孵化鸡蛋等事宜,或者你可以支付一些硬货币,跳过这些关卡。因此,付费如同光明正大的利用手段。另外,“跳过解决方案”也属于这一类型:游戏为玩家提供了利用1个硬货币便可跳过艰难挑战的机会。

装扮道具

上述三角模式有意忽略了毫无价值的美感道具,比如装扮或地位道具。虽然纯粹的美感道具是游戏体验中令人愉快的一部分(比如《Restaurant City》中的壁纸与《军团要塞》中的帽子),但它们不会影响游戏的趣味性。而趣味性是这个三角模式极力保护的一个元素,只要它能受到保护,那我们便可以按照自己的想法出售大量装扮道具。

有时,玩家喜欢在游戏中为他人提供虚拟圣诞树。为何我们不允许这种行为呢?(本文为游戏邦/gamerboom.com编译,拒绝任何不保留版权的转载,如需转载请联系:游戏邦)

The Free-To-Play Triangle [Game Economics]

by Tadhg Kelly

I often see free-to-play game designs where every interaction is a potential monetisation path. These games want to sell energy, buffs, character unlocks, aesthetic items, rule adjustments, experience points and so on. Usually this is because their developers are trying to make the business cases for their games. By showing that all roads lead to cash, the hope is that the project will be signed off.

Creating many roads to monetisation might sound good but there’s a point beyond which it becomes pay-to-win. At that point the game loses a reason to be played, and players sense it. You can sell a lot within a game, but its important to always have at least one dimension of it that can’t be bought as that ensures the motivation to play. So I’ve created the Free-to-Play Triangle, which you can hopefully use to sanity-check your economy.

Follow Tadhg Kelly

Pay-to-Cheat or Pay-to-Win

There’s a big difference between a cheat and an exploit. A cheat is an out-of-context influence that subverts a game, leading to one or more players winning all (or almost all) of the time.

Cheats are considered unfair and rob the player of a reason to play. Cheats also tend to break the magic-circle, making the frame naked for all to see and destroying the game’s ability to be thaumatic.

An exploit, on the other hand, is an in-context influence. Exploits are quirky consequences of rules, unexpected outcomes of experimentation and emergent compound effects. Since the play brain is largely wired to decode and master game systems, exploits are often considered good as long as they don’t lead to dominant tactics. In a sense, interesting game systems are built with the intent of being exploited.

Good free-to-play design can be described as “pay-to-exploit”, whereas bad free-to-play design could be called “pay-to-cheat” or “pay-to-win”. Pay-to-exploit gives the player an economic path to getting ahead of the curve in a way that feels in-context. Whereas pay-to-cheat simply breaks the game.

In paying to exploit the player is not removing the challenge of the game. He may buy more Poker chips but he still has to play to win. That bigger sword may make fights easier, but he still has to actually fight. The sources of fascination, pressure and the need to solve (which collectively I call “urgency”) remain. So the game’s dynamic stays intact.

Accidental Effects

The typical pay-to-exploit involves paying for a resource that you do not have rather than slogging through gameplay to get it. Usually this is done via the intermediary of a hard currency – such as “cash” or “gold” – easy to buy but tough to earn. So the goal is to encourage some exploit behaviours for money, but for the game to still be fun. Most developers understand this in principle, however they design a pay-to-cheat economy anyway.

This happens in three ways:

The first is a simple failure of game balance. They might sell a kind of weapon so totally out of whack with the rest of the game, or has a use case which the designer never foresaw, that results in a dominant tactic. These kinds of pay-to-cheats are easy to spot and not hard to fix. However they can lead to pretty bad customer service issues if many of your top players have invested in the item before it is corrected.

The second kind occurs when multiple kinds of purchase stack upon one another, leading to a pay-to-win. Suppose you can pay to get the better sword, but also to beat the big boss that you would use it on. Or you can get the big sword and also buy the experience points that you need to level up so that the fight becomes trivial. And suppose you can do that repeatedly. This is how the game loses its fun.

The final kind of pay-to-cheat economy is the deliberately-created one. In this scenario, the developer purposefully attaches a money tax to as many actions as possible. Interestingly this is often phrased as a matter of player choice. So what, says the developer, big deal if they can buy their way through? It’s their choice, their game, their play time, right?

These defences of pay-to-cheat last up until the moment that metrics show a lack of retention. If you make a game that is nothing but elastic customisations for the player to buy then it loses that sense of being a game. A game is played to be entertained – and that requires delivering some genuine value to the player, not rationalising it away.

Gameplay Pinch-points

Fun is (as I have often said) “the joy of winning while mastering fair game dynamics”. It’s only one of many joys that players can feel (exploration, delight, beauty, thrill, empathy, etc) but it is the foundational one. For any game to be played over the medium or long term it has to be fun. No exceptions.

To some economists, charging for everything seems entirely reasonable, a way to attract “whale” players and have them keep spending. If every part of the game is chargeable then every part of the game will be bought. However the game designer understands that if all sources of urgency are solvable with cash, then for most whale or minnow players the fun disappears.

Well-designed fun is multi-dimensional. It permits tactics through the interplay of different kinds of interaction, leading to emergent outcomes and strategies. Games which are uni-dimensional tend to only be fun if they are motivated by a big prize (lotteries) or require the extreme application of a physical skill (many athletic events). The key to finding fun is determining whether the application of multi-dimensional interaction to overcome urgency is worth doing.

Another way to look at these challenges is as “pinch-points”. A pinch-point occurs in any economy where concerns over supply lead to outsized changes of price. In free-to-play games the phrase is often used to describe high-priced economic transactions that the player finds preferable to alternatives.

Game challenges are also pinch-points: The player needs to master the difficult challenge for fun, and is willing to spend a high price in time, skill or resources to get there. If so then – for a free-to-play game to remain fun – at least one type of pinch-point needs to remain out-of-bounds to hard currency. This is where a triangle becomes useful.

The Triangle

In project management they say: “Fast, Cheap, Good. Pick Two.”

Although every project is complicated, this simple phrase identifies the three common dimensions of all projects and stipulates that planning should only ever treat two of them as fixed. If you have a low budget and need it quick, don’t expect many features. If you need great features and have a hard deadline, expect it to cost. That way, quality of delivery is ensured.

In a similar vein, I’ve lately thought that free-to-play economies should use a triangle to ensure that the gameplay has some pinch-points which cannot be bought. If you restrict yourself to the triangle, the idea goes, you are less likely to create a pay-to-cheat economy.

It looks like this:

Boosters

A booster is a temporary enhancement. It’s a special weapon with only a few shots, a temporary invulnerability shield, a token which turns all of the blue jewels to red, etcetera. Boosters are a major feature of action/arcade games and are often used to extend the basic dynamic of the game for limited periods. Many games also encourage tactical usage, offering the player an inventory area in which to hold their boosters and use them at moments of their choosing.

Bejewelled Blitz, for example, allows the player to buy boosters using the game’s hard currency. Using the boosters the player can clear rows, causing big changes in the game environment and enhance his score. However he still has to actually match 3 jewels repeatedly inside a minute. That’s the gameplay pinch point.

Another example booster is the purchase of chips. In poker and slots, for instance, the player uses chips as a form of currency to make bets in the hope of winning more. As he starts to lose, he often buys more of the chips to boost his chances of getting back into the game and win. He might, but the extra chip effect could only ever be considered temporary.

Unlocks

While a booster is temporary, an unlock is permanent. The player gets access to an item or feature that she would otherwise have to play for, and this affects the rest of her game. In sim-style social games, for example, many of the items that the player would use to populate her environment are locked behind a level meter. She would have to play the game for a long period of time, amassing experience points, until those items became available. Alternatively she can often spend hard currency to get there early.

Unlocks cover many areas, from new cars (CSR Racing) to enhancements to the game world. Temple Run, for example, allows the player to buy upgrades to pickups (objects that she collects).

She still has to collect those pickups though (a gameplay pinch-point of skill). Sim games commonly allow particular buildings to be unlocked early for a cash cost. Those buildings then go on to ease land or coin-generating issues that the player may have, but are still governed by the overall rules of population or territorial resources (the gameplay pinch-point).

Skips

The third kind of free-to-play sale is the skip: A very common example of a skip is “energy”. The game meters the frequency of high-value actions (such as harvesting or building) over time, regenerating one point every X (commonly 5) minutes. It sells packs of energy to the player for small amounts of hard currency, which extend play time.

A second type of skip is the “social skip”. In some social games there are specific activities that require the player to enroll the help of his friends. In essence the game presents a choice: get your friends to click on an advertisement for the game in your name (such as a Facebook request), or pay to skip this.

Neither energy nor social skips provide much value. Instead they simply say to the player “If you want to play some more, you must pay up or do something awkward”. Skips are among the most cheated aspect of social games as a result. Social skips, for example, lead to the formation of groups of players who all friend each other. They are also why free-to-play games remain unpopular with self-described gamers, as they are pretty sleazy.

However there are better types of skip.

One is “wait time”. In this case the player is able to interact as much as he likes with the game, but many of the actions that he takes are metered by a clock. The building has to be built, the egg hatched and so forth. Or you can pay a little hard currency to skip ahead. So paying feels like an exploit, which is the light side of the force. Another kind is the

“solution skip”: the game offers an option to skip a difficult chalenge with a hard currency spend. These are not yet common, but who knows?

What About Decorations?

The triangle intentionally ignores aesthetic items with no gameplay value, such as decorations or status items. While purely aesthetic objects can be a delightful part of any game experience (from wallpaper choices in Restaurant City to hats in Team Fortress), they do not affect the fun of the game. The fun is what the triangle seeks to protect, and as long as it is protected I see no reason why you can’t sell as many decorations as you want.

Sometimes players like to give each other virtual Christmas trees in-game. Why not let them?(source:whatgamesare)

闽公网安备35020302001549号

闽公网安备35020302001549号