探讨电子游戏运用非致命元素的可行性

作者:Christoph Kaindel

“沙盒故事情节的理念就是为玩家提供一个大型的开放式场景,其中填满大量有趣互动的机会。玩家不必拘泥于轨道般的线性情节,他们可以选择任意互动顺序。如果正确地构建游戏场景,就能产生故事般的体验。”

上文引自Ernest Adams的专栏文章,他总结的概念可能成为开放式场景中冒险类游戏和角色扮演游戏的下一步进展。为了实行沙盒故事情节,Adams建议将从属于玩家的事件同脱离玩家的事件结合起来。也就是说,在无玩家参与下(只要他们不是情节中的关键),游戏场景中的事物应继续变化发展。

作为玩家,我沉浸于享受开放式场景游戏。我喜欢自由、发现、发生出乎意料事情的感觉;然而,作为历史学家,我忍不住将游戏场景同真实社会进行比较。即使我知道游戏场景需要精简,我仍旧觉得游戏应该追随一些额外的复杂性,应该从真实社会结构中汲取灵感。

以下是关于中世纪晚期的城市生活如何启发建立可信游戏场景的构想,比如RPG或者沙盒式的动作冒险游戏。由于我主要的调查对象是中世纪时代每天发生的暴力事件,所以我将关注:为名誉和尊严而战,遵从严厉的不成文规定——大多数情况为非致命。

杀戮或者被杀

在我看来,从《吃豆人》及《太空入侵者》时代开始,暴力游戏的本质从未改变过。大多数游戏“使用暴力”的情况仍然归结为:“那里的家伙是你的敌人。把你的枪对准他们,在你被杀前杀了他们。”游戏暴力通常意味着玩家之间的战斗,抑或是玩家与AI控制对手之间的战斗;这两种情形都是,敌人只是你在游戏前进的过程中需移除的障碍。

这与真实世界的暴力现象完全不同。真实生活中,人们因多种不同原因使用暴力,比如为了达到不同目标、为了满足多种需求。人们受到贪婪、恐惧、奢侈、憎恶、纯粹无聊等等的刺激,从而实施暴力,大多数这些做法不适合引入游戏中。我仍然坚信,如果游戏设计者能更多考虑真实世界中暴力的多层含义与作用,而不只是制作大量杀敌的视觉盛宴,游戏中的暴力以及游戏的结局将会以多种有趣的方式呈现出来。

然而讽刺的是,游戏广告和大量游戏暴力评论家却总在强调暴力游戏中所谓的“真实感”。虽然单从视觉层面上看,有些游戏确实如此,但是大多数游戏中的战斗场面仍追随动作电影的效果,尽管命值再生系统允许更多攻击性的玩法,但这两者都并不具有“真实感”。

大多数游戏中,玩家的动机都特别简单。玩家角色为一个士兵,其职责就是战胜一群头脑简单的侵略性对手。所以,电子游戏中的暴力通常是致命的,因为需要消灭前进途中的敌人才可以完成任务。敌人从不撤退、也不投降。一旦战斗打响,唯一的结局通常是,要么敌人灭亡,要么玩家角色完蛋——游戏结束或者迫使玩家下载最近保存的版本。

这种模式适用于直线型射击游戏;毕竟,一个士兵不期望能同敌方士兵或者可恶的侵略者进行争论。然而开放式场景游戏力图为玩家营造“逼真的”环境,接近真实世界——我希望这样的设置可以提供更多的战斗选择。

直到几十年前(甚至是如今的一些地方或社会)——为名誉而战并不是非致对手于死地的解决方法。尽管它已淡出现实生活的视野,但我想它至少可以用于暴力游戏的历史背景或虚拟场景设置。

中世纪城市中的日常暴力行为

作为历史学家,我已经用几十年的时间调查了有关中世纪晚期及近代欧洲发生的非正式暴力行为的话题——实质都是有关酒馆争吵和刀战。直到最近(1995年以来),犯罪历史学家才公正地看待了这一话题。犯罪史大多与法律条文的制定无关,但与社会处理犯罪的方式有关——例如罪行的定义,犯罪行为是如何组织的,应采取怎样的制裁方式,谁应该接受惩罚等。

中世纪时代常常称为暴力时期。以现代欧洲的标准来看,中世纪晚期的城市是个险恶的地方;然而,在市民眼中,相较于道路及城市周围森林的危险度,城市更加安全。

当局曾试图禁止市民在拥挤地方(游戏邦注:比如酒馆、妓院、澡堂和教堂等频繁在节假日发生打斗行为的地方)携带武器,但却无果而终。虽然战斗中经常使用短剑,然而战斗极少以一方的死亡告终,大多情况只会造成外伤。展示一个人战斗的勇气与决心就足以保全他们的面子了。

男人常常为名誉而战,我们将其定义为保护个人地盘、荣誉、家庭、家园、财产、权利和特权的能力。在公众面前受到侮辱会引发争吵或者刀战。战争的目的不是为了杀敌,而只是为了在公众面前战胜他人。

为名誉而战是必须的;如果一个人允许自己的尊严任人践踏,那么再也不会有人与他来往,他也会丧失社会地位。所以,甚至是高层官员与名人都可以参与到公开的争斗中,虽然其对手往往是一些同僚。

每个群体都有一个有别于其他群体的荣誉观。现代研究表明,为荣誉而战构成了无警察及官方相对弱势的社会中的一种自律形式。所以,形式化的战斗对社会而言,更多的是积极作用,而不是破坏因素。它只是向对手以及“观众”发送的一种信号;它是社会各阶层成人的一种交流手段。

中世纪每天发生的冲突常会催生出一条不成文的法则。这种冲突的升级始于侮辱他人,比如抓起他们的衣领,撞倒他们的帽子(帽子是地位的标志),把他们推到在地,最后拔出刀剑,拳脚相加。动作可能大得夸张;一场争吵如同真正的战斗一样,为了一饱观众/目击者眼福,更多展示的是作战技能。旁观者的介入可能会中止冲突升级。

法律一般会宽容对待公共场合发生的名誉之战。如果有人受伤,那么他的对手就得根据受伤程度支付罚款。如果斗争者被杀死,那么凶手将被放逐多年。然而,暗杀某人却是一条死罪,谋杀者常被执行死刑。偷窃被定义为可耻的行为,且比公共暴力的性质更严重,所以惩罚更严苛。同时,对外来者的惩罚会比对市民来得更严酷。

还有其它形式更规范的公共战斗:骑士联赛、学校击剑及竞技展示、舞台战斗、摔跤比赛、司法决斗和双人对决。

骑士联赛、学校击剑和摔跤比赛都称为“格斗项目”,虽然它们真的不符合当代对“运动”的定义。13世纪起,骑士联赛在各个城市出现,因为只有城市才可以为参加者及随从提供住宿。骑士联赛是一场丰富多彩的视觉盛宴。在那段日子里,有各种各样的比赛和竞赛,骑马战斗和徒步战斗,到了晚上,有酒会、舞会和化妆舞会。只有富裕的骑士、贵族和参加者才可以参加骑士联赛。

而击剑比赛则允许普通人士展示他们操纵宝剑、短剑、长剑和各种武器的技能。他们在无保护设备下进行战斗,但是大多数危险的技术都是禁止的——比如刺杀剑术、用拳头连续击打、扔。如果使用非法手段,在场的裁判员随时准备介入其中。

舞台战斗由专业战士表演,但其中看不中用,只用于愉悦观众的花拳绣腿常被剑术高手所鄙视。他们是17世纪和18世纪获得英国表彰的战士先驱,后者常用的一种剑术风格可能会致对方流血,但只会是外伤。

摔跤为中世纪时期广受农民以及贵族喜爱的运动。摔跤是中世纪格斗系统中唯一至今基本不变的一项运动。例如,奥地利的Ranggeln和瑞士的Schwingen,都是直接从中世纪的摔跤衍生出来的。

几百年来,战斗中的审判一直是司法体系中的一部分,只在14世纪放弃使用。作为严峻的考验,司法决斗的基本前提是上帝会帮助无辜者获胜。对手常常会雇佣剑术专家为他们备战,或者雇佣冠军代替他们上场。普通人士通常着紧身亚麻布的服装上场,骑士和贵族则佩带盔甲。裁判负责整场战役。司法决斗可能以一方的死亡告终,如果战斗进行到傍晚时分,一方离开作战区域或者裁判的介入也可以终止比赛。

双人对决可能衍生于决斗裁判法。一场正规的双人对决需要几个目击者在场。然而16世纪和17世纪的双人对决常常为街头打斗。只要稍加挑衅,大学生之间就会决斗,所以剑术课程是他们的重要学习内容——其地位等同于舞蹈课,这两门课通常由同一位老师教授,因为他们的步法相似。

观众可以观看所有这些形式的战斗;所以,为个人尊严和名誉而战便具有重要作用,而观众的出席也会影响战斗发挥情况。

采取哪种战斗与其场景及使用的武器有关。摔跤是击剑的基础,只要有机会随时都可以展现摔跤。短剑战斗与摔跤非常相似,双方的距离一样,短剑战斗常用于加强摔跤的博倒及夹住对方的手段。有无盔甲的战斗性质显然不一样;在对付穿着盔甲的对手时,刺剑几乎没有作用,所以要使用钉头锤或者战锤或者“半剑”(一种特殊的宝剑战斗风格)这类可以破坏盔甲的武器。

虽然,现代欧洲社会常在法庭上维护个人尊严,而公开决斗已经被体育运动所边缘化,但如今年轻的帮派和其它以暴力团体仍然恪守上述荣誉观以及一些暴力仪式。

比如,街头阿飞在体育馆外参加所谓的“骑士联赛”。双方“竞争对手”的数量一致。战斗按严格的规则进行——要么使用“装备”,要么卸下。因此,小流氓配备着打棒球用的木棒、刀、斧头、大砍刀、链条等等。通常裁判会出席确认倒下的一方输掉比赛,以此决定哪方获胜。赢得这样的比赛意味着获得国际威望;他们还在网络上设置了排行榜。这也是为何他们会提前训练,组织对打的原因。

因此,总结如下:在暴力频繁发生的社会,战斗是一种交流方式。赢得战斗可以提升个人荣誉及社会地位;即使输了,至少能保住荣誉。接下来我将提出一些设想,如何让非致命的战斗融合在中世纪或者幻想题材的游戏场景中。这些基本理念也适用于现代游戏领域。

沙盒游戏中的非致命战斗

开放式场景游戏以非致命战斗为主

接近于我所描述的个人荣誉的游戏概念,是《黑道圣徒2》的“风格”等级或者《荒野大镖客》中的“名气”等级,不过后部作品还有补充“名气”等级的“荣誉”等级(记录玩家行为好坏),这类似于《辐射3》和《无名英雄》中的“因果报应”元素。然而这些游戏中的战斗都是致命的;我们无法只是征服对手就可以赢得荣誉。

我注意到只有一些沙盒游戏使用非致命暴力玩法元素,尽管大多数战斗都可能致死。《骇客任务》系列允许玩家在不杀死任何人的情况下完成游戏;但是无意识的角色仍会从游戏中消失(他们可能会被同盟者唤醒);人们在游戏中使用暴力、致命或者非致命手段都只是为了移除障碍。我将以上述方式讨论以暴力作为交流形式的游戏。

在2006年的《教父》中,玩家角色不得不威胁店主支付保护费。我们需要找到每位店主的一个固定弱点,然后将其运用于小游戏中,当然不能杀了店主。所以应小心使用游戏中更加复杂的无武装的战斗系统。

这种恐吓任务演变成一种比较规范的第三人称射击游戏,而且它们正适合组织犯罪的游戏场景。奇怪的是,在《侠客猎车手4》这种在多个方面与其相似的游戏中,无武器的战斗也是可能的,但只会出现在1至2个任务中。我发现对于大多数的游戏而言,这一系统基本上不管用。

摔跤游戏并不能算是沙盒游戏,但是我发现它们是将非致命战斗和角色扮演元素结合在一起的有趣类型。与其它角色扮演游戏相比,如果你在摔跤游戏中输了一场战斗,故事情节仍会继续向不同方向发展。你在排行榜中的位置也会变化,但是你仍会在游戏中。

专业摔跤好比是TV肥皂剧,两名个性鲜明的演员在互相较劲,其中会交织着一些或大或小的故事情节,这通常会持续几个月甚至几年;剧情因爱与恨、忠诚与背叛,勇气和胆小等话题不断向前发展。然而,摔跤也是一幕道德剧,正如正义战胜邪恶的斗争。因此,个人尊严是摔跤中最重要的因素。

有一个奇怪的悖论是:专业摔跤都是表演型的,而摔跤游戏呈现的却是真正的格斗场景。众所周知,观众的认可会影响战斗结局。所以,与其它格斗游戏相比,在大多数摔跤游戏中,你不仅要战胜对手,也要通过华丽且多变的技能来博得观众的好感;只有这样你才可以完美谢幕。所以,这是唯一认为展示战斗技能同战斗本身一样重要的动作游戏——如同中世纪时期的仪式化战斗。

在Rockstar公司推出的《学院坏小子》中经常会发生打斗,但完全没有血腥及致命的场景出现——这种战斗风格适用于以美国小城镇寄宿学校为背景的游戏场景。玩家角色——即Jimmy Hopkins这个叛逆少年不得不面临以恃强凌弱为乐的社会青年的欺侮,同时他也参加学校的拳击比赛和摔跤小组。这所学校就是一个暴力场所;你通常会看到懦弱的学生遭受强者的欺负。你可以侮辱其他学生,但也可以通过道歉或者掏钱请求独处来逃避战斗——这是我知道的唯一会增加暴力进程或减少暴力进程的游戏。

如果Jimmy被大人抓住或者输掉一场战斗,那他不会死掉,只是会被送回自己的房间。因为游戏中没有人会死掉,所以Jimmy会在不同情境中多次碰到相同的人物,这有助于了解他们并同他们建立关系和激发冲突。打败某个小团体的成员会得到这一对手的尊敬。游戏中会上演许多种搞怪事件,比如,把人推进废纸箱,扔鸡蛋和炮竹或者使用弹弓打破窗户。

《学园坏小子》是将时间的流逝融入叙述情节中的极少数开放式场景游戏之一。游戏中的一天以学校课程为主;如果Jimmy上课期间在外面被抓,他将被强制上学。游戏中也存在四季:游戏始于秋天,继续过渡到冬天和夏天。在主要剧情总结后,你在夏天就有机会完成剩下的任务。

我认为《学园坏小子》中最有趣的是强加于主角的限制,这些都是游戏场景中逻辑性元素。其游戏场景比《侠盗猎车手》中的任何一个场景都小,毕竟青少年的世界往往没有成人的世界那么大。

因为Jimmy是个少年,所以不允许开车。他不得不有规律地上课。虽然他将成为游戏进程中富有灵活的斗士,可以打败游戏中所有其他的孩子,但他仍然生活在一个由无敌的成年人统治的世界里——有时他可以逃出他们的控制,但是他不能打败他们。所有这些元素——尊严、非致命的形式化暴力、暴力冲突的升级、成人的无敌控制、时间流逝等,在我看来都可以极大地增加《学园坏小子》游戏场景的可信度。

常规事件及程序任务的制定

虽然开放式场景游戏通常有昼夜周期且需耗上几个月的时间,但是没有玩家的参与,就不会有循环事件的发生。我在《荒野大镖客》的教堂里花了几十天时间,但是我没有看到任何一个弥撒。所有的社会都是以诸如此类的习俗建立起来。比如,教堂礼拜、每周的赶集日、假期和有着舞蹈、比赛、运动以及不同种竞赛的节日等常规事件会打破了中世纪城市的日常生活。其它不定期事件的发生可能是外贸物品到达港口,一队入侵者在邻近村庄抢劫,当地伯爵的访问,学生暴乱,征税,强盗头目被执行死刑等等。

如果是在游戏中,类似于《刺客信条》,玩家可以选择观看或者参与这些事件。所有这些事件可能会催生额外任务或者活动,错过它们不会破坏游戏进程。因为之后会再次发生,所以玩家会有第二次机会拯救强盗头目。

在城市中,拥挤的地方往往是危险地带,比如酒馆、妓院、集会场所或者窄桥,但是在战斗中丧生的危险性较小。玩家角色进入酒馆可能会挑起战斗,或者避免作战。

危险的地方也可能是随机分支任务生成的源头:一个人请求玩家协助对付一个对手——而这个对手可能会记恨玩家并在几天后带上朋友向玩家重新发起挑战。我知道《天际》中就曾出现类似的随机分支任务;可是我并不清楚它们是否只是一次性事件,还是之后它们会产生结局。

另一种使游戏场景更生动的方式是允许主要的NPC(非玩家角色)追求自己目标,类似于《全面战争》系列这种战略游戏的反对派系。荣誉的概念会是其中的一部分。以个人荣誉为主的游戏场景可能是在人口密集的区域,玩家角色及非玩家角色会接受非致命的战斗,然而谋杀会受到惩罚。

NPC需要荣誉等级来引导他们的行动;他们不仅仅是装饰品或者任务交付者,他们需跟随自己的固定目标,依靠变量来定义自己的角色。虽然游戏需要包含基于代理人的模拟元素,但并不需要成为一个复杂的模拟社会,却需要提供有利于产生有趣场景的互动方式,比如Espen Aarseth在《上古卷轴:湮没》中体验到的独特历程。

NPC的数据可能包括贪婪、好战、宽恕、流行、酗酒、多情、敌对等等。当双方需要互动时,他们可以基于NPC等级选择是否加入战斗——想象含有短剑元素的《模拟人生》。在观众面前,玩家角色(或者NPC)为荣誉而战通常是非致命的,它会以获得或者丧失尊严/地位而告终。赢得/失去尊严的多少与观众的数量有关。所以,NPC之间的关系会随着时间发展而变化,可能会激起冲突,也会解决冲突,玩家可能会参与,或者不参与。一连串的分支任务可能会在这些情境中发展。

作为玩家及NPC行动的推动力,个人尊严与荣誉可能会导致游戏目标的不断变化,这与主要剧情无关:

短期目标:展示出个人勇气的行动与互动

中期目标:装备和储备(包括衣服、房子、马/车、武器)

长期目标:游戏世界中的社会地位

玩家争取这类目标很正常,但对NPC而言却不一样。我们仍需撰写主要任务,但是主要的NPC可以“完全自由”地实现自己的抱负吗?这可以增添游戏的乐趣吗?或者导致游戏的不可玩性?游戏难以预测的本质会增加重玩价值,但可能也会增加将社会模拟、战略游戏和动作冒险三者 混合的设计难度。

格斗项目、决斗及展示战斗

非致命战斗的简单应用可能是在游戏场景中引入不同的格斗项目,从而限制玩家的战斗风格,比如禁止致命技能或者限制使用盔甲和武器。奇怪的是,这些很少运用于游戏中。许多游戏展示出一些竞技战斗,但大多数情况下,对于《湮没》或者《无主之地》(2009年版)这类游戏来说,其结果都是致命的。

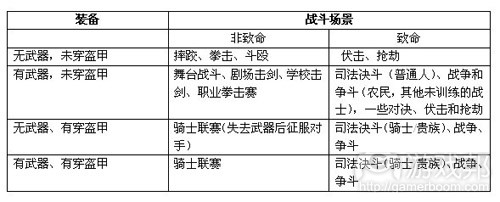

我尝试将发生在中世纪和早期现代世界的大多数战斗场景归纳成一个简单的表格。我们会看到八项显著的(虽然常有重叠)“作战风格”:

这种复杂的系统可能并不适用于游戏。但是在骑士联赛式的场景中,战斗可能会局限于非致命手段。据我所知,马上长枪比武,只以小游戏的形式出现在1987年的《王冠守护者》及其重制版本中,《 Conqueror A.D. 1086》情况也颇为相似。在这些游戏中你可能会赢得或者失去荣誉、金币或者竞技中的土地;有些重要的东西常会处于险境,但你的生命却不会。

你原先可能会在对抗一个强大的对手时失败,但是不久你可能会更有技巧地打败他。骑士联赛和其它非致命的战斗形式就是以此激发和启动一长串的任务。比如,玩家角色早期可能会目睹一场声势浩大的骑士联赛,知道只有在几十个小时后,自己才可以参加这样的赛事,并在之后可能赢得很大的奖励。

其它战斗场景也可以经过调整使其适用于游戏。例如,战斗可能会聘请玩家角色作为决斗审判。或者请求她指导一个加入对决挑战,但比较笨拙的贵族。与生死战不同,展示战斗需要使用愉悦观众的技巧,或者类似摔跤游戏(比如世界摔角娱乐系列)中的系统。在剧场表演中,玩家角色必须保证战斗不会伤害到对方。所以,运用游戏内置的格斗项目及展示战斗,会适使玩家去适应作战风格,增加打败对手的多样手段。

非致命作战游戏的优势

在真实或虚拟世界中,非致命战斗在含义及影响上均与生死战截然不同。电影中(中世纪历史)打败的对手过后常常会成为英雄的朋友——但这种情节从来不会发生在游戏中。许多西部电影中的酒吧争吵常作为喜剧情节穿插其中,但也可能是致命的对决。这些都会植入到电影和电脑游戏中。Rockstar因为忽略了《荒野大镖客》中的争吵机制而错过了一大机会。是的,赢得所有酒吧的打架会收获战利品,但是我仍旧喜欢能够测试我战斗技能的任务。

非致命战斗通常运用于游戏的起始阶段,慢慢展开剧情,如同《刺客信条2》中的发展一样。不久,随着冲突的加剧以及事态的扩大,战斗开始转向致命方向。一旦发生致命暴力行为,它会对玩家产生更大的影响。使用非致命战斗而不是致命战斗,可以打破许多游戏中安全地带与危险区域之间泾渭分明的界线。

比如,一座虚幻的城市本该是安全的:玩家角色在城市中可能会碰到争吵,但是她不会被杀。修道院是很安全的,但是外面的树林具有潜在的危险性。在彻底安全及非常危险区域之间会有灰色过渡阶段,而玩家仍能够随时清楚自己是否处于危险中。

死亡、重载或者重生总是会破坏游戏的沉浸感。另一方面,输掉一场非致命战斗却让玩家有机会获得一些分支任务:玩家角色可能需要找到医生来给自己疗伤;或者拜访教练以备下一场战役;或者只是自己申请训练。

如果战斗的结局和杀伤力与对手、旁观者的位置、数量及是否加入战斗有关,那么玩家需要决定采用什么技能和武器。土匪的伏击可以是一场生死战,但酒馆里的醉酒冲突却不应该发生死亡事件。如果发生战斗,玩家通常可以选择是否参与;在某些情况下,我们甚至可以让玩家在虚张声势中结束一场战斗。

总结:威尼斯的桥梁战役——现成的历史游戏背景

描写威尼斯的著名文化,是为了表明我的主要观点。几百年来(始于第二个14世纪中期,持续到18世纪),威尼斯的居民总会定时看到横跨运河上的大型桥梁发生的模拟战斗。

起初,这些模拟战斗使用削尖的木棒;到了1600年,发展到了无武器的战斗——拳头之战。这些战斗大小不一,从几十个人到上千人,吸引了上千的观众用租来的阳台、船以及附近房子的屋顶观看这些战役。这种打斗是危险的;许多打斗者严重受伤甚至掉入运河中淹死。在1574年,600个手持棍棒的斗士发起了桥梁战役,以此向法国国王亨利三世致敬;在进行了激烈的三个小时的战斗后,据说国王惊呼道:“这场战役的规模不足以构成战争,但从惨烈程度来看绝非一场儿戏!”

威尼斯的拳击手因其技能而享誉整个意大利;但是他们不是专业的战士——他们是渔民,工匠或者店主。他们加入战斗是因为模拟战斗会提升他们作为行业头目、领袖或者普通工人的等级,从而提高他们的社会地位,除此以外,别无其它优势。

guerre di pugni是常规的战斗事件,主要为提升个人尊严而战。以桥梁战役为基础的游戏可能是争斗游戏、动作冒险游戏、角色扮演游戏或者实时战略游戏。它甚至可以转换成一个虚拟故事情节,其中漂浮的城市由巨大桥梁连接着,而这些桥梁是玩家需要攻克的对象。或者它也可以作为《刺客信条》的扩展内容。 (本文为游戏邦/gamerboom.com编译,拒绝任何不保留版权的转载,如需转载请联系:游戏邦)

When Violence Meets Honor in History and Games

by Christoph Kaindel

[Consultant Christoph Kaindel takes a look at the real reasons and methods behind fights in history, offering up a few ideas for howeveryday life in a late medieval city might be taken as inspiration for building believable game worlds for RPGs or sandbox-style action adventures.]

“In sandbox storytelling, the idea is to give the player a big open world populated with opportunities for interesting interactions. The player isn’t constrained to a rail-like linear plot, but can interact with the world in any order that he chooses. If the world is constructed correctly, a story-like experience should emerge.

This quote from a column by Ernest Adams sums up a concept that might be the next step in the evolution of open world adventure games and role playing games. To make sandbox storytelling work, Adams suggests a combination of player-dependent and player-independent events. In other words, things should keep moving and changing in the game world without the player’s intervention, as long as they are not critically important for the plot.

As a player, I immensely enjoy playing open world games. I love the sense of freedom, of discovery, of unexpected things happening; as a historian, however, I can’t help comparing game worlds to real societies. Even though I realize that game worlds need to be simplified, I feel that many games could benefit from a little extra complexity, inspired by the structure of real societies.

Here are a few ideas how everyday life in a late medieval city might be taken as inspiration for building believable game worlds for RPGs or sandbox-style action adventures. As my main research subject was everyday violence in the middle ages, I will focus on that: the fight for fame and honor, following strict unwritten rules — and in most cases non-lethal.

Kill or Be Killed

The essence of violence in games has, in my opinion, not changed a lot since the days of Pac-Man and Space Invaders. In most games, “doing violence” can still be summed up as: “The guys over there are your enemies. Point your gun at them and kill them before they kill you.” Game violence usually means combat among players or between players and AI-controlled opponents; in both cases, enemies are just obstacles to be removed in order to progress in the game.

This has very little to do with real world violence. In real life, people use violence for many different reasons, to reach many different goals, to fulfill many different needs. People are motivated by greed, by fear, by lust, by hate, by sheer boredom, and there are many ways of acting violently, most of which are not fit to be used in games. Still, I believe if game designers took a little more time to consider the many meanings and uses of real-world violence instead of just making killing more and more visually spectacular, game violence and its consequences might be shown in more varied and interesting ways.

Ironically, game advertisements as well as critics of excessive game violence place a lot of emphasis on the purportedly “realistic” depiction of violence in games. While on the purely visual level, this may hold true for some games, combat in the majority of games follows action movie conventions, and while medpacks and regenerating health allow for more aggressive play, neither, of course, is “realistic”.

Player motivation in most games is quite simple. The player character often is a soldier just doing her duty fighting hordes of single-mindedly aggressive opponents. Therefore, violence in video games is usually lethal, as enemies need to be removed on the way to completion of a mission. They never retreat; they never surrender. Once a fight has started, the only possible outcome is usually death for either enemy or player character — ending the game and forcing the player to load a recent save.

This is a pattern that works reasonably well in linear shooter games; after all, a soldier would not be expected to argue with enemy soldiers or alien abominations. But open world games strive to give the impression of a “living, breathing” environment that is close to the real world — and in such a setting I expect to have a wider range of combat options.

Until a few decades ago — in some places and societies even nowadays — the fight for honor was a non-lethal way of dealing with an opponent. Even though it has fallen out of use in real life, I think it might be well suited as a model of game violence to be used at least in historical or fantasy settings.

Everyday Violence in the Medieval City

As a historian, I have done several years’ research on the topic of informal everyday violence in late medieval and early modern Europe — in essence, tavern brawls and knife fights. This topic has only fairly recently been picked up by crime historians, since about 1995. The history of crime is not so much concerned with written law codices, but more with how society copes with crime: what is considered a crime, how the persecution of criminals is organized, what punishments are applied, who is punished — and who is not.

The Middle Ages are generally seen as a rather violent period. A late medieval city was a dangerous place by modern European standards; it was, however, considered safe by its citizens, compared to the hazards of the roads and forests around it.

Authorities tried to ban, unsuccessfully, the wearing of weapons in crowded places like taverns, brothels, bathhouses, and churches, where fights broke out frequently, mostly on holidays and weekends. Though daggers were often used, fights rarely ended in the death of one of the fighters; in most cases only superficial wounds were inflicted. Demonstrating one’s courage and willingness to fight was often enough to keep face.

Men usually fought in defense of their personal honor, defined as the ability to protect one’s personal space, reputation, family, home, possessions, rights and privileges. Insults in public escalated to brawls or knife fights. The goal was not to kill, but only to publicly defeat the other person.

Violent defense of personal honor was a necessity; if a man allowed his honor to be damaged, nobody would do business with him anymore, and he would lose social status. Therefore, even high city officials and nobles engaged in public fights, though only with their equals.

The concept of honor defines a group and differentiates it from other groups. Modern research suggests that the fight for honor constituted a form of self-regulation in a society that had no police and relatively weak central authorities. So, ritualized fighting was a constructive rather than a destructive element of society. It was used to make a point, to send a signal to the opponent as well as the “audience”; it was part of the communicative repertoire of adult men of all levels of society.

Everyday conflicts in the Middle Ages usually followed an unwritten code of conduct. The sequence of escalation started with insulting the other person, grabbing their lapels, knocking off their hat (a status sign), shoving them to the ground and, finally, drawing the dagger and fighting with fists and knife. Movements probably tended to be big and theatrical; a brawl was as much a display of fighting prowess for the benefit of spectators/witnesses as it was a real fight. The escalation sequence could be broken by intervention of bystanders.

The law treated these honorable fights in public places rather leniently. If somebody was wounded, his adversary had to pay a fine according to the seriousness of the wound. If a fighter was killed, the killer was banished from the city for several years. Cowardly murdering a person from behind, on the other hand, was a capital crime, and the murderer was usually executed.

Theft was considered dishonorable and therefore much worse than public violence, and punishment was stricter. Also, punishment was always harsher for strangers than for citizens.

There also were other, more regulated forms of public fighting: tournaments, fencing schools and exhibitions, stage fights, wrestling contests, judicial combat and, later, duels.

To tournaments, fencing schools, and wrestling contests the term “combat sports” might be applied, though they do not really fit the modern definition of “sport”. From the 13th century onwards, tournaments were staged in cities, as only a city could provide accommodation for the hundreds of participants and their retinue. Tournaments were colorful spectacles. During the day there would be contests, jousts in several varieties, mounted group combat (mêlée) and foot combat, in the evenings banquets, dances and masquerades. Only rich knights, nobles and patricians could afford to participate in a tournament.

On the other hand, the fechtschule (fencing contest) allowed commoners to show their skill in handling swords, daggers, staffs and other weapons. They fought without protective equipment, but the most dangerous techniques — thrusting, pommel strikes, throws — were forbidden. A referee stood ready to interfere if illegal means were used.

Staged show fights were performed by professional Klopffechter, who were despised by fencing masters for their ineffective but flamboyant style aimed at pleasing the audience. They were the predecessors of the English prize fighters of the 17th and 18th centuries, who probably used a style of fencing that produced bloody, but only superficial wounds.

In the Middle Ages, wrestling was a popular pastime for peasants and nobles alike. Wrestling is the only medieval fighting system that has, as folk tradition, survived hardly changed until today. Austrian Ranggeln and Swiss Schwingen, for instance, are direct descendants of medieval wrestling.

Trial by combat was part of the judicial system for hundreds of years, falling out of use in the 14th century. The basic premise of judicial combat as an ordeal was that God would help the innocent to gain victory. Opponents were often allowed to hire a fencing master to prepare them for battle, or even a champion to fight in their stead. Commoners usually fought in close-fitting linen garments, knights and nobles in full armor. A judge would preside over the fight. Judicial combat might end in the death of one fighter, but nightfall, leaving the combat area or the judge’s intervention could also end the fight.

The duel probably evolved out of the trial by combat. A formal duel required a challenge and the presence of several witnesses. Many duels of the 16th and 17th centuries, however, were nothing more than street fights. University students were notorious to duel at the slightest provocation; fencing lessons therefore were an important part of their studies — as well as dancing lessons, and often taught by the same teacher, because the footwork was similar.

In all of these forms of combat, spectators were present; and so, the defense and advancement of personal honor and reputation played a major part, and the presence of spectators certainly had some influence on the way the fight was conducted.

Combat was different depending on the situation and on the weapons used. Wrestling was the basis of fencing and might be applied whenever the opportunity presented itself. Dagger fighting was quite close to wrestling; the fighting distance was the same, and daggers were often used as levers to enhance wrestling throws and locks. There was a big difference between fighting unarmored or in full armor; against the latter, sword blows had almost no effect, so armor-breaking weapons like maces or war hammers or a special sword fighting style called “half-swording” were used.

Though in modern European societies personal honor is usually defended in court, and public fighting has been officially relegated to the realm of sports, today’s youth gangs and other violence-prone male groups still adhere to the concept of male honor described above, along with violent rituals.

Hooligans, for instance, take part in “tournaments” outside stadiums. The number of “competitors” on either side is the same. The fights are organized according to strict rules — either with “equipment” or without it. And thus, hooligans are equipped with baseball bats, knives, axes, machetes, chains, etc. Often referees are present to assure that those who are down are taken out of the fight, and to decide which side has won. To win such a fight means to gain international prestige; there are online leaderboards for hooligans. That is why hooligan groups train beforehand and organize sparring fights.

So, to summarize: in violence-prone societies, fighting is a form of communication. Winning a fight increases personal honor and social status; by participating in a fight, and losing, honor may at least be preserved. In the following part I will propose a few ideas how non-lethal combat might be integrated in a medieval or fantasy game world. In a modern game world, the basic ideas could still be used.

Non-Lethal Combat in a Sandbox

Open world games featuring non-lethal combat

Game concepts close to the use of personal honor I described are the “style” rating of Saints Row 2or the “fame” rating of Red Dead Redemption, though in the latter game this is supplemented by an “honor” rating to keep track of the player’s good or evil deeds, similar to the “karma” of Fallout 3and Infamous. But combat in these games is lethal; there is no way to win fame by just subduing an opponent.

There are only a few sandbox games I am aware of that use non-lethal violence as an element of gameplay, even though most fights may be of the deadly variety. The Deus Ex series is famous for allowing players to finish the games without killing anybody; but unconscious characters are still taken out of the game (they may be awakened by their comrades); violence, lethal or non-lethal, is only used to remove obstacles. I will focus on those games that also use violence as a form of communication, in the way I outlined above.

In 2006′s The Godfather, the player character has to intimidate shopkeepers to make them pay protection money. Each shopkeeper has a certain weak spot that has to be discovered and then exploited in a kind of minigame, and of course shopkeepers should not be killed. So, the game’s rather complex unarmed combat system has to be used carefully.

The intimidation missions bring some variety into a fairly standard third person shooter, and they fit appropriately into a game world of organized crime. Strangely, in Grand Theft Auto IV, a similar game in many ways, unarmed combat is also possible, but it is never really needed except in one or two missions. I found it fairly useless for most of the game.

Wrestling games don’t exactly qualify as sandbox games, but I find them very interesting as a genre that combines non-lethal fighting with role playing elements. Contrary to many other role playing games, if you lose a fight in a wrestling game, the storyline continues, only in a different direction. Your position in the ranking list may change, but you will always stay in the game.

Professional wrestling itself has been compared to TV soap operas; both feature actors with clear-cut different personae interacting in changing constellations in a small number of locations. There are bigger and smaller interwoven storylines, often going on for several months or even years; driving forces are love and hate, loyalty and betrayal, courage and cowardice. Wrestling, however, is also presented as a morality play, as the big fight of Good against Evil. And finally, in wrestling, personal honor is all-important.

There is a strange paradox: professional wrestling is staged, but in wrestling games it is presented as a real combat sport. It is acknowledged, though, that audience approval makes a difference to the outcome of the fight. So, in contrast to other fighting games, in most wrestling games you not only have to overcome your opponent, but also win over the audience by performing flashy and varied techniques; only then will you be able to perform a finishing move. This is therefore the only type of action game in which the display of fighting skills is as important as the fight itself — as it was in the ritualized fights in the Middle Ages.

In Rockstar’s Bully (aka Canis Canem Edit) fights happen frequently but are entirely bloodless and non-lethal — the fighting style is well adapted to the game world of a boarding school in a small American town. The player character — Jimmy Hopkins, a rebellious teenager — has to take on several gangs of bullies, but also fight in the boxing ring or in the school’s wrestling team. The school is a violent place; often you will see weaker students bullied and pushed about by stronger ones. You can insult other students, but you can also get out of a conflict by apologizing or paying for being left alone — this is the only game I know that has a violent escalation/de-escalation process.

If Jimmy is caught by an adult or loses a fight, he does not die but is just transported back to his room. As nobody ever dies, Jimmy will confront some people several times in different circumstances, which helps in getting to know them and developing relationships as well as conflicts. Defeating members of one faction will earn respect with their rivals. Several kinds of pranks can be performed, from pushing people into wastepaper baskets to throwing eggs and fireworks or breaking windows using a slingshot.

Bully is one of the few open world games that incorporates the passing of time into its narrative. The game day is structured around school lessons; if Jimmy is caught outside during a lesson, he will be forced to attend. There are also seasons: the game starts in autumn and continues through winter and spring. After the conclusion of the main storyline, in summer, you have the opportunity to finish all remaining side missions.

What I found most interesting in Bully were the restrictions imposed on the main character, all of them logical elements of the game world. The game world is a lot smaller than in one of the GTA games, reflecting the fact that a teenager’s world is smaller than an adult’s.

As a teenager, Jimmy is not allowed to drive cars. He has to attend class regularly. Though he will become a skillful fighter during the course of the game and will be able to beat all the other kids in the game, he still lives in a world ruled by grownups, who are invincible — he can sometimes escape from their grasp, but he can not defeat them. All these elements — the use of honor, non-lethal ritualized violence as a way of life, escalation of violent conflicts, the dominance and invulnerability of adults, and the passage of time — in my opinion immensely increased the believability of Bully’s game world.

Regular events and Procedural Mission Creation

Though open world games often have day-night cycles and are played for months of game time, no recurring events happen without the player’s participation. I spent several days in the churches of Red Dead Redemption, but I did not witness a single Holy Mass. All societies are structured around rituals like these. For instance, regular events breaking the daily routine of medieval city life included church service, weekly market days, holidays and festivals with dances, races, sports and different kinds of contests. Other events happening at irregular intervals could be trade goods arriving at the harbor, bands of raiders plundering nearby villages, a visit by the local count, student riots, tax collection, the execution of a robber baron and so on.

If it were a game, similar to the Assassin’s Creed world, the player might be given a choice to watch or to participate. All these events could instigate side missions or activities, and missing them should not be game-breaking. They will happen again later in the game, so the player will have another chance at, say, rescuing a robber baron.

In cities, crowded places would be dangerous, like taverns, brothels, guildhalls, or narrow bridges, but there would be little danger of dying in a fight. A player character might enter a tavern to pick a fight, or she might avoid them.

Dangerous places may also be a source of randomly generated side missions: a person asking the player for help against an opponent — who might then hold a grudge against the player and return with friends a few days later. I am aware that Skyrim offers random side missions like these; but I do not know if they are all strictly one-shot or if they may have consequences later on。

Another way to make the game world feel more alive would be to give major NPCs a bit of freedom to follow goals of their own, similar to opposing factions in strategy games like the Total War series. The concept of honor could be a part of this. The basic premise for a game world using the concept of personal honor would be that in populated areas non-lethal combat is acceptable for player character and NPCs alike, but murder would be punished.

NPCs should have an honor rating that guides their actions; instead of just being decoration or quest givers, they should follow certain goals of their own, depending on variables defining their character. Though the game would have to contain agent-based simulation elements, it would not need to be a complex society sim, but provide interactions that allow interesting situations to emerge, like those unique “transgressive” play experiences Espen Aarseth describes [pdf link] that happened to him while playing The Elder Scrolls IV: Oblivion. Of course, if a game is designed to produce these situations regularly, they do not constitute transgressive play anymore.

NPC stats might include Greedy, Belligerent, Forgiving, Popular, Alcoholic, Amourous, Hostile against X (insert other NPC) and so on. Getting into a fight should be one option NPCs have when interacting with each other, depending on their ratings — imagine The Sims with daggers. Fights for honor among player characters and/or NPCs in front of an audience will usually be non-lethal and end in honor/status gain or loss with its consequences. The amount of honor gain/loss might depend on the number of spectators. That way, relationships between NPCs can change over time, conflicts may arise and be resolved, and the player/s may be involved or not. Strings of side missions could evolve out of these situations.

Personal honor and reputation as a driving force for player and NPC actions could lead to dynamically changing game goals, independent from the main storyline:

Short term goals: Actions and Interactions that demonstrate personal courage

Medium term goals: Appearance and possessions (clothes, house, horse/car, weapons)

Long term goals: Social position in the game world

It is common for players to strive for goals like these, but not for NPCs. Main quests would still have to be scripted, but could major NPCs be given “free rein” to follow their built-in ambitions? Would this add to the fun of the game, or would it make it unplayable? The unpredictable nature of the game would add to replayability, but probably also lead to difficulties trying to design such a mix between society sim, strategy game and action adventure.

Combat Sports, Duels and Show Fights

A simple application of non-lethal combat would be the introduction of different combat sports to the game world that would impose certain restrictions upon the player’s fighting style, for instance by disallowing deadly techniques or limiting the use of armor and weapons. Strangely, this is rarely done in games. Many games feature some sort of arena combat, but most often, like in Oblivion or Borderlands (2009), this is just anything-goes and to the death.

I have tried to put the multitude of combat situations that occurred in the Medieval and Early Modern world in a simple roster. We could say there were eight distinct (though often overlapping, technique-wise) “fighting styles”:

The use of such a complex system probably would not be feasible in a game. But combat in tournament-like situations could be restricted to non-lethal means. Jousting, as far as I know, only appeared as a mini-game in 1987′s Defender of the Crown and its remakes, and the somewhat similar Conqueror A.D. 1086. In these games you could win or lose honor, gold or land in the joust; important things were at stake, just not your life.

You might lose against a formidable opponent at first, but later you might be more skilled and defeat him. In that way, tournaments and other non-lethal combat forms can be used as motivation and to start a string of missions. For instance, the player character might witness a great tournament early on in the game, knowing that only many game hours later she, too, will be able to take part in such an event, and still later maybe able to win the big prize.

Other combat situations also could be easily adapted for use in games. The player character might be hired as champion for a trial by combat. Or she may be asked to instruct a clumsy noble, who has been challenged to a duel, in the art of fencing. Show fights, other than life-or-death combat, would require employing techniques that please the audience, a system similar to that used in wrestling games like the WWESmackdownseries. In a theater performance, the player character would have to fight convincingly without hurting their opponent. So, using in-game combat sports and show fights, the player would be forced to adapt her fighting style, adding variety to combat encounters.

Advantages of Non-Lethal Game Combat

Non-lethal fights, in the real world as well as in fictional worlds, have different meanings and impact than combat for life and death. In movies (and medieval epics) opponents that are defeated in single combat often become the hero’s friends afterward — never in games. In many movie westerns, there are barroom brawls, often used as comic relief, but there is the deadly duel at high noon as well. Both have a place in movies as well as computer games. Rockstar missed a great opportunity by neglecting the brawling mechanic in Red Dead Redemption. Yes, there is a trophy for winning brawls in all the saloons, but I would have loved some missions that tested my brawling skills as well.

Non-lethal fighting might be used in the beginning of a game, to start things off slowly, as it is done in Assassin’s Creed II. Later on, as conflicts deepen and things become more serious, combat may become lethal. This way, deadly violence, when it happens, has much more impact on the player.

Using non-lethal fighting in addition to lethal combat breaks up the strict dichotomy between safe zones and danger zones that exist in many games.

For instance, a fantasy (quasi-medieval) city would be reasonably safe: the player character might be involved in a brawl, but she will not be killed. A monastery would be completely safe, but the woods outside would be dangerous. This way, there would be shades of gray between completely safe and very dangerous areas, and the player would still know the danger she was in any time.

Dying and reloading or respawning always breaks game immersion. Losing a non-lethal fight, on the other hand, is an opportunity for some side quests: the player character may need to look for a doctor to patch her up; or visit a trainer to prepare her for the next fight; or just put in a training session by herself.

If the outcome and lethality of the fight depends on opponents, location and number and participation of bystanders, the player always has to decide what tactics and what weapons to use. An ambush by bandits would be a life or death affair, but it would not be allowed to kill a drunk assaulting the player character in a city tavern. If a fight happens, the player should often have a choice to participate or not; in some cases it might even be possible to end a fight in the escalation phase by bluffing.

Conclusion: Venetian Bridge Battles – A Ready-Made Historical Game Setting

The description of a little-known feature of Venetian popular culture may serve to illustrate my key arguments. For hundreds of years, starting with the second half of the 14th century and lasting until the early 1700s, the citizens of Venice regularly met in mock battles upon the larger bridges spanning the canals.

At first those battagliole were fought with sharpened sticks; by 1600, they became unarmed brawls known as guerre di pugni, the wars of the fists. These fights that could vary in size between a few dozen to a thousand participants drew thousands of spectators who watched from rented balconies, gondolas or the roofs of nearby houses. The fights were dangerous; many fighters were severely wounded or even drowned in the canals. In 1574, 600 stick fighters gathered for a bridge battle in honor of the French king Henri III; after three hours of fierce fighting, the king is said to have exclaimed: “This is too small to be war, but too cruel to be a game!”

Venetian boxers were famed for their skill throughout Italy; but they were no professional warriors — they were fishermen, craftsmen or shopkeepers. They took part because by fighting in the battagliole and rising through the ranks to be a capo, a leader, a simple worker could increase his social status in a way that would be impossible to achieve otherwise.

The guerre di pugni were regular combat events, fought mainly to increase personal honor. A game based on these bridge battles might be a brawler, an action adventure, a role playing game, or even a real time strategy game. It might even be transformed into a fantasy tale in which floating cities are connected by giant bridges that have to be conquered. Or it might just be an add-on to Assassin’s Creed. I think Ezio Auditore would feel right at home in it.(source:gamasutra)

闽公网安备35020302001549号

闽公网安备35020302001549号